Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Vigilance Theory

Transféré par

Anonymous 18nFluUDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Vigilance Theory

Transféré par

Anonymous 18nFluUDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Szalma

Vigilance and Sustained Attention

VIGILANCE

AND

SUSTAINED ATTENTION

Instructor: P.A. Hancock

Introduction

Vigilance, or sustained attention, refers to the ability to monitor

displays for stimulus events over prolonged periods of time.

The term

vigilance as applied to human behavior was coined by Sir Henry Head

(1923), who referred to it as a state of maximum physiological and

psychological readiness to react. However, the origin of modern vigilance

research, as in many other areas of human factors, was in the Second World

War. The British Royal Air Force were employing a new technology, RADAR,

in their aircraft to scan for German U-boats sinking allied shipping and

impairing the Anglo-American war effort. These were highly motivated and

skilled operators, and yet they were missing targets. Norman H. Mackworth

was assigned the task of determining why motivated and skilled airmen were

missing signals (although see Ditchburn, 1943). He devised the Clock Test

which consisted of a blank-faced clock and a black pointer that would make

movements of .3 inches per second. Observers were to monitor this display

for the occurrence of double jumps of .6 inches. The length of the session

of the original experiment was 2 hours. The figure in the second PowerPoint

slide shows the results he observed (Mackworth, 1948). Observers ability to

detect signals declined over the course of the vigil, with the steepest decline

early in the watch. This progressive decline in the quality of performance

over the course of a watch keeping session is one of the most ubiquitous

effects in vigilance (See, Howe, Warm, & Dember, 1995), and is referred to

as the decrement function

or the vigilance decrement (Davies &

Parasuraman, 1982). The decrement has been observed in both laboratory

and field settings, across a variety of domains.

These include RADAR,

SONAR, cytological screening, anesthesia gauge monitoring, nuclear power

plant operation, industrial quality control, baggage screening, and detection

Szalma

Vigilance and Sustained Attention

of criminal or insurgent activity (e.g., friend/foe identification during long

shifts). Vigilance is

also a

component

of

tasks

requiring sustained

performance, such as shift work and driving.

Theories of Vigilance

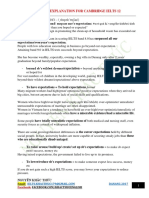

Inhibition Theory. Since Mackworths (1948) original findings there

have been several theories of vigilance, and the progression of theoretical

change has mirrored general trends in psychology.

Thus, the earliest

explanations for vigilance relied on behaviorist theories, particularly the

Hullian (Hull, 1943) theory dominant at that time. The central construct for

this view was inhibition. Inhibition was conceived as a force opposing the

tendency of organisms to expend energy through behavior. Inhibition can be

overcome by either stopping the behavior for some period of time (e.g., a

rest

break),

allowing

the

inhibition

reinforcements for the behavior.

to

dissipate,

or

by

providing

The process of inhibition was therefore

similar to that observed in extinction in conditioning experiments. According

to this perspective, vigilance declines because of a progressive rise in

response inhibition. Data were reported that were consistent with this view,

that knowledge of results (reinforcement) increases detection responses,

and that performance improves after brief rest periods, presumably a

reflection of dissipation of inhibition.

In addition, introducing a novel

stimulus event can re-establish vigilance levels to levels obtained at the

beginning of the watch, a process known as dis-inhibition.

However, inhibition theory cannot explain why in some cases

performance never declines during the watch-keeping session, while in other

cases performance is poor from the very beginning of the vigil. In addition,

the operators responses may not always decline over time. In other words,

sustained attention may decline over time, but the number of responses may

remain relatively stable. However, one of the most problematic empirical

findings for this theory was that increasing signal probability, which should

Szalma

Vigilance and Sustained Attention

increase inhibition and thereby decrease performance, actually improves

vigilance.

Expectancy Theory. The decline of behavioristic and drive-based

theories of behavior led to a cognitive revolution in psychology (Dember,

1974).

The

information

processing

manifestations of this shift.

theories

of

the

1950s

were

Although Broadbent (1958) applied his

attentional filter theory to vigilance, the evidence has not strongly supported

his assertions (see Craig, 1985; but see also Broadbent, 1971). During this

same time period, the expectancy theory of vigilance emerged. Expectancy

theory was not intended to explain the performance decrement, but rather to

account for findings problematic for inhibition theory: maintenance of a low

but persistent level of responding, and the increase in responding as a

function of signal probability. The theory, first presented by Baker (1959),

asserts that observers expectancies regarding signal events often differ

from reality, and this discrepancy accounts for the response patterns

observed in vigilance experiments. Thus, observers adjust their level of

responses (and thereby their level of detections) according to the perceived

signal frequency and their prior experiences on the task or similar tasks.

Expectancy can also account for the increase in conservatism with time on

watch, since observers may learn that the signals they are looking for are

rare and adjust their responding accordingly (Craig, 1978). Although this

theory still has utility in explaining response bias effects and responses by

observers to changes in signal and event rate, it does not provide a complete

explanation for vigilance effects. An attempt to more fully explain vigilance

was emerged with the application of arousal theory.

Arousal Theory. This theory draws on the inverted-U model of arousal

attributed the Yerkes and Dodson (1908) but actually presented in its most

recognized form by Hebb (1955). According to this view, an individuals level

of vigilance depends on their arousal, and the performance decrement

Szalma

Vigilance and Sustained Attention

results from under-arousal resulting from the under stimulating environment

of the vigilance task. While there is some evidence for this contention (e.g.,

electro-cortical activity and autonomic activity tends to decline during a vigil;

see Davies & Parasuraman, 1982), arousal theory cannot account for the

high stress levels associated with vigilance. For instance, vigilance is

associated with increased levels of catecholamine (e.g., see Frankenhaeuser,

Nordheden, Myrsten, & Post, 1971), which is associated with the endocrine

systems response to stress, and observers report more symptoms of stress

before a vigil than prior to its start (for a review, see Szalma, 1999).

addition,

because

arousal

theory

argues

that

vigilance

tasks

In

are

underarousing, the mental workload associated with such tasks should be

low. However, it has been well established that the workload of vigilance is,

in fact, quite high (Warm, Dember, & Hancock, 1996).

Resource Theory. The problems associated with the arousal theory of

vigilance coincided with the problem of unitary arousal theories in general.

Resource theory (Kahneman, 1973; Moray, 1967; Navon & Gopher, 1979;

Norman & Bobrow, 1975) emerged as an alternative to arousal theory, and it

was adopted as a theory of vigilance. Thus, according to resource theory, an

individuals vigilance depends on the mental capacities or resources that

can be allocated to the task. The concept of resources draws on economic

and thermodynamic metaphors, utilizing the notions of supply and demand

for the former and pools of energy or processing units available for the

latter. According to this theory, the performance decrement occurs because

individuals expend resources for maintaining attention at a rate faster than

they can be replenished (Parasuraman, Warm, & Dember, 1987). This theory

is consistent with empirical findings related to tests of the vigilance

taxonomy (Warm & Dember, 1998) and with the findings in regard to

workload (Warm, Dember, & Hancock, 1996) and stress (Szalma, 1999).

However, as extensive as the favorable evidence is, it is still difficult to argue

that the data support resource theory. This is because it is very difficult (and

Szalma

Vigilance and Sustained Attention

may be impossible; but see Szalma & Hancock, 2002) to test the concept of

resources itself. Like other constructs in psychology, resources are difficult to

define operationally, and therefore difficult to empirically test. The future of

this theory in general and as a theory of vigilance rests on current and future

efforts to understand what resources are.

The Vigilance Taxonomy

By the early 1970s it was clear that whether performance decrements

were observed depended in part on task characteristics. However, it was

unclear what task properties were important determinants. Parasuraman and

Davies (1977) noted that although the correlations in performance across

task types were low, they were not zero. They derived a taxonomic scheme

for classifying vigilance tasks in categories according to sensory modality,

number of sources to be monitored (source complexity), the rate of stimulus

events (event rate), and memory load. For the last category Parasuraman

and Davies (1977) distinguished between tasks that required observers to

compare a stimulus to a standard held in memory (successive tasks requiring

absolute judgment) from those tasks in which the standard and the test

stimulus were both presented (simultaneous tasks requiring comparative

judgment). In an extensive review of the literature they observed that the

vigilance decrement only occurred for certain categories of task. Specifically,

they found that performance decrements were most likely to occur with

successive tasks at high event rate (event rates> 24 events per minute) with

multiple sources to be monitored. In regard to modality, visual tasks elicited

lower performance levels than auditory tasks (but see Hatfield & Loeb,

1968). Later meta-analytic work (See, Howe, Warm, & Dember, 1995)

confirmed that event rate was a major determinant to vigilance performance,

but they also found that there was evidence that the decrement can be

obtained for both successive and simultaneous tasks. In addition, they also

reported

differences

discrimination

from

between

those

tasks

that

that

imposed

required

cognitive

primarily

sensory

demands

(e.g.,

Szalma

Vigilance and Sustained Attention

mathematical calculations), and suggested that the sensory/cognitive

distinction be added as an additional taxonomic category.

The Psychophysics of Vigilance

In addition to the taxonomic categories, there are psychophysical

variables that influence performance in vigilance.

These include modality

and complexity, which are also categories of the taxonomy, as well as signal

salience (conspicuity), event rate, signal rate, and spatial and temporal

uncertainty. In class we will review the effects of each of these categories on

vigilance performance, as well as the influence of feedback and cueing on

performance and transfer of training (but see also Warm & Jerison, 1984).

Current Learning Objectives

The objective for the unit on vigilance is to provide you with an

introduction to the phenomenon, its importance in human factors, the

relevant characteristics of vigilance tasks, and theories of vigilance. Thus, if

you understand the taxonomy and the theoretical issues surrounding

vigilance, and the factors that influence performance, workload, and stress in

vigilance, you will gain an understanding of how to avoid the problem in

design and how to account for vigilance effects that may occur in your

research. In addition, it will be important for you to understand the relations

among

measures

of

performance,

workload,

and

stress

(i.e.,

associations/dissociations).

References

Baker, C.H. (1959). Attention to visual displays during a vigilance task: II. Maintaining the level of

vigilance. British Journal of Psychology, 50, 30-36.

Broadbent, D.E. (1958). Perception and communication. London: Pergamon Press.

Broadbent, D.E. (1971). Decision and stress. New York: Academic Press.

Craig, A. (1978). Is the vigilance decrement simply a response toward probability matching?

Human Factors, 20, 441-446.

Craig, A. (1985). Vigilance: Theories and laboratory studies. In: S. Folkard and T.H. Monk (Eds.), Hours

Szalma

Vigilance and Sustained Attention

of work. (pp. 107-121).Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Davies, D.R., & Parasuraman, R. (1982). The psychology of vigilance. London: Academic Press.

Dember, W.N. (1974). Motivation and the cognitive revolution. American Psychologist, 29, 161-168.

Ditchburn, R.W. (1943). Some factors affecting the efficiency of work by lookouts (Report No.

ARC/R1/84/46/0). Admiralty Research Laboratory.

Frankenhaeuser, M., Nordheden, B., Myrsten, A.L., & Post, B. (1971). Psychophysiological

reactions to understimulation and overstimulation. Acta Psychologica, 35, 298-308.

Hatfield, J.L., & Loeb, M. (1968). Sense mode and coupling in a vigilance task. Perception &

Psychophysics, 4, 29-36.

Head, H. (1923). The conception of nervous and mental energy. II. Vigilance: A physiological

state of the nervous system. British Journal of Psychology, 14, 126-147.

Hebb, D. O. (1955). Drives and the CNS (conceptual nervous system). Psychological Review, 62, 243254.

Hull, C.L. (1943). Principles of behavior: An introduction to behavior theory. New York: Appleton.

Kahneman, D. (1973). Attention and effort. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Mackworth, N.H. (1948). The breakdown of vigilance during prolonged visual search. Quarterly

Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1, 6-21.

Moray, N. (1967). Where is capacity limited? A survey and a model. Acta Psychologica, 27, 84-92.

Navon, D., & Gopher, D. (1979). On the economy of the human information processing system.

Psychological Review, 86, 214-255.

Norman, D., & Bobrow, D. (1975). On data-limited and resource-limited processing. Journal of Cognitive

Psychology, 7, 44-60.

Parasuraman, R., & Davies, D.R. (1977). A taxonomic analysis of vigilance performance. In: R.R.

Mackie (Ed.), Vigilance: Theory, operational performance, and physiological correlates. (pp. 559574). New York: Plenum Press.

Parasuraman, R., Warm, J.S., & Dember, W.N. (1987). Vigilance: Taxonomy and utility. In L.S. Mark,

J.S. Warm, & R.L. Huston (Eds.), Ergonomics and human factors: Recent research (pp. 11-32).

New York: Springer-Verlag.

See, J.E., Howe, S.R., Warm, J.S., & Dember, W.N. (1995). A meta-analysis of the sensitivity

decrement in vigilance. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 230-249.

Szalma, J.L. (1999). Sensory and temporal determinants of workload and stress in sustained attention.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

Szalma, J.L., & Hancock, P.A. (2002). On mental resources and performance under stress. Unpublished

Szalma

Vigilance and Sustained Attention

white paper, MIT2 Laboratory, University of Central Florida. Available at www.mit.ucf.edu

Warm, J.S., & Dember, W.N. (1998). Tests of a vigilance taxonomy. In R.R. Hoffman, M.F. Sherrick, &

J.S. Warm (Eds.), Viewing psychology as a whole: The integrative science of William N. Dember

(pp. 87-112). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Warm, J.S., Dember, W.N., & Hancock, P.A. (1996). Vigilance and workload in automated systems.

In R. Parasuraman & M. Mouloua (Eds.), Automation and human performance: Theory and

applications (pp. 183-200) Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Warm, J.S., & Jerison, H.J. (1984). The psychophysics of vigilance. In: J.S. Warm (Ed.), Sustained

attention in human performance. (pp. 15-59). Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley.

Yerkes, R.M., & Dodson, J.D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation.

Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459-482.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Accesare - Resursa 1Document17 pagesAccesare - Resursa 1Flory FloricaPas encore d'évaluation

- Behavioral Models of Impulsivity in Relation To ADHD: Translation Between Clinical and Preclinical StudiesDocument17 pagesBehavioral Models of Impulsivity in Relation To ADHD: Translation Between Clinical and Preclinical StudiesJose EscobarPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Control and Its Relationship to Stress LevelsDocument33 pagesPersonal Control and Its Relationship to Stress LevelsNyoman YogiswaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Hobfoll ModelDocument12 pagesHobfoll Modeladri90Pas encore d'évaluation

- Working Memory Capacity Attention Control and Fluid IntelligenceDocument19 pagesWorking Memory Capacity Attention Control and Fluid IntelligenceDanilkaPas encore d'évaluation

- P Emotion Attention and The Startle ReflexDocument19 pagesP Emotion Attention and The Startle ReflexbmakworoPas encore d'évaluation

- 24 Time For The Fourth Dimension in Attention: Anna C. (Kia) Nobre Gustavo RohenkohlDocument40 pages24 Time For The Fourth Dimension in Attention: Anna C. (Kia) Nobre Gustavo RohenkohlSuresh KrishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Experimental and Theoretical Approaches to Conscious ProcessingDocument28 pagesExperimental and Theoretical Approaches to Conscious Processingt0035Pas encore d'évaluation

- European Journal of Parapsychology v24-2 2009Document51 pagesEuropean Journal of Parapsychology v24-2 2009digger257100% (1)

- 10.1162@089892901753294400Document22 pages10.1162@089892901753294400hlbg.udenarPas encore d'évaluation

- 373 1471 1 PBDocument9 pages373 1471 1 PBsureshPas encore d'évaluation

- Lovibond, P.F., & Shanks, P.R. (2002) - The Role of Awareness in Pavlovian Conditioning. Empirical Evidence and Theoretical ImplicationsDocument24 pagesLovibond, P.F., & Shanks, P.R. (2002) - The Role of Awareness in Pavlovian Conditioning. Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Implicationscarlos andres baez manriquePas encore d'évaluation

- Motivation PerformanceDocument6 pagesMotivation PerformanceMark TaylorPas encore d'évaluation

- Jov 5 5 1Document29 pagesJov 5 5 1hPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 Devonport PCDocument12 pages01 Devonport PCInten Dwi Puspa DewiPas encore d'évaluation

- Pupil Dilation During Visual Target DetectionDocument14 pagesPupil Dilation During Visual Target DetectionShane G MoonPas encore d'évaluation

- Hint Z Man Caul Ton Curran 94Document15 pagesHint Z Man Caul Ton Curran 94Denisa BalajPas encore d'évaluation

- Andreassi - ConceptsDocument31 pagesAndreassi - ConceptsJuan MurilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Systematic Desensitization As A Counterconditioning ProcessDocument9 pagesSystematic Desensitization As A Counterconditioning ProcessJef_8Pas encore d'évaluation

- How Stimuli Generated by Avoiding Shock Are Inherently ReinforcingDocument23 pagesHow Stimuli Generated by Avoiding Shock Are Inherently ReinforcinggonurcelayPas encore d'évaluation

- COGNITIVE SWITCHING AND SUSTAINED ATTENTION by Adam HarleyDocument46 pagesCOGNITIVE SWITCHING AND SUSTAINED ATTENTION by Adam HarleyMark MassengalePas encore d'évaluation

- Slocum Et Al. (2018)Document9 pagesSlocum Et Al. (2018)Lai SantiagoPas encore d'évaluation

- Go L Diamond 1958Document39 pagesGo L Diamond 1958Delia BucurPas encore d'évaluation

- The Interactive Effects of Variety, Autonomy, and Feedback On Attitudes and PerformanceDocument28 pagesThe Interactive Effects of Variety, Autonomy, and Feedback On Attitudes and PerformanceJavier CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychological Review Response Deprivation ApproachDocument19 pagesPsychological Review Response Deprivation Approachlaura sanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Article of Kia NobreDocument13 pagesArticle of Kia NobrePedro Alejandro VelásquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Chronometry: Beyond Onset Latencies in The Lexical Decision TaskDocument14 pagesMental Chronometry: Beyond Onset Latencies in The Lexical Decision TaskpratolectusPas encore d'évaluation

- Farmacologia Pa TraducirDocument10 pagesFarmacologia Pa TraducirlaxtoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dual - Process Evidence - From - Event-Related - PotentialsDocument19 pagesDual - Process Evidence - From - Event-Related - PotentialsFrancisco SaltoPas encore d'évaluation

- Calgani et al (2020)Document20 pagesCalgani et al (2020)jorge9000000Pas encore d'évaluation

- Confusion and Compensation in Visual Perception: Effects of Spatiotemporal Proximity and Selective AttentionDocument22 pagesConfusion and Compensation in Visual Perception: Effects of Spatiotemporal Proximity and Selective AttentionFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- Running From William James Bear A Review of Preattentive Mechanisms and Their Contributions To Emotional ExperienceDocument31 pagesRunning From William James Bear A Review of Preattentive Mechanisms and Their Contributions To Emotional ExperienceDaniel Jann CotiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Spatial Four-Alternative Forced-Choice Method Is The Preferred Psychophysical Method For Naı Ve ObserversDocument16 pagesSpatial Four-Alternative Forced-Choice Method Is The Preferred Psychophysical Method For Naı Ve Observersbonobo2000Pas encore d'évaluation

- Universite: Rate)Document13 pagesUniversite: Rate)José HernándezPas encore d'évaluation

- Human - Performance - Under - Sustained - Operat20151127 6440 A9djjs With Cover Page v2Document11 pagesHuman - Performance - Under - Sustained - Operat20151127 6440 A9djjs With Cover Page v2Aljho AljhoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Sleep Deprivation On Decision Making - ReviewDocument14 pagesThe Impact of Sleep Deprivation On Decision Making - ReviewAna Viegas100% (1)

- Fanselow1994 Article NeuralOrganizationOfTheDefensiDocument10 pagesFanselow1994 Article NeuralOrganizationOfTheDefensiJuani RoldánPas encore d'évaluation

- Vigilance and Sustained AttentionDocument2 pagesVigilance and Sustained AttentionMabel Joy ComighudPas encore d'évaluation

- Riemer Et Al - 2012 - Psychophysics of Reproduction PDFDocument8 pagesRiemer Et Al - 2012 - Psychophysics of Reproduction PDFjsaccuzzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Vaitl 2005Document4 pagesVaitl 2005Nicolas Pineros BarreraPas encore d'évaluation

- Pastore and Scheirer, 1974 (TDS - General)Document14 pagesPastore and Scheirer, 1974 (TDS - General)LeonardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Shaw 2013Document9 pagesShaw 2013PatriciaMGarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy and NeuroscienceDocument19 pagesPhilosophy and NeuroscienceRandy AlzatePas encore d'évaluation

- Taylor & McCloskey 1996 Selection of Motor Responses On The Basis of Unperceived StimuliDocument5 pagesTaylor & McCloskey 1996 Selection of Motor Responses On The Basis of Unperceived StimulihooriePas encore d'évaluation

- Theta/Beta Ratio and Attentional Control: An Exploratory StudyDocument43 pagesTheta/Beta Ratio and Attentional Control: An Exploratory StudyBernardo SteinbergPas encore d'évaluation

- Data AnalysisDocument9 pagesData AnalysisSara PerezPas encore d'évaluation

- Atención 3Document27 pagesAtención 3leidyPas encore d'évaluation

- MacLennan Elements of Consciousness and Neurodynamical CorrelatesDocument16 pagesMacLennan Elements of Consciousness and Neurodynamical CorrelatesBJMacLennanPas encore d'évaluation

- Conscious Contributions To Subliminal Priming: Piotr Jas KowskiDocument12 pagesConscious Contributions To Subliminal Priming: Piotr Jas KowskiLaura TanasePas encore d'évaluation

- Operant ConditioningDocument25 pagesOperant ConditioningGis EscobarPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 9Document14 pagesUnit 9sindhusankaridevuPas encore d'évaluation

- experimDocument8 pagesexperimAna-Maria CiobanuPas encore d'évaluation

- 16 - Burgos (2007) - Autoshaping and AutomaintenanceDocument16 pages16 - Burgos (2007) - Autoshaping and AutomaintenanceMiguel AguayiPas encore d'évaluation

- Load Theory of Selective Attention and Cognitive ControlDocument16 pagesLoad Theory of Selective Attention and Cognitive ControlXyz ZyxPas encore d'évaluation

- Toward A Psychological Theory of Multidimensional Activation (Arousal) PDFDocument34 pagesToward A Psychological Theory of Multidimensional Activation (Arousal) PDFCC TAPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Environmental Psychology - KaplanDocument14 pagesJournal of Environmental Psychology - KaplanMaría Espinosa100% (1)

- Exposure Therapy: Rethinking the Model - Refining the MethodD'EverandExposure Therapy: Rethinking the Model - Refining the MethodPeter NeudeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods in Psychobiology: Specialized Laboratory Techniques in Neuropsychology and NeurobiologyD'EverandMethods in Psychobiology: Specialized Laboratory Techniques in Neuropsychology and NeurobiologyR. D. MyersPas encore d'évaluation

- Detection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationD'EverandDetection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationArthur MacNeill Horton, Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Advantages and Disadvantages of The DronesDocument43 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of The DronesVysual ScapePas encore d'évaluation

- Amana PLE8317W2 Service ManualDocument113 pagesAmana PLE8317W2 Service ManualSchneksPas encore d'évaluation

- JD - Software Developer - Thesqua - Re GroupDocument2 pagesJD - Software Developer - Thesqua - Re GroupPrateek GahlanPas encore d'évaluation

- Abinisio GDE HelpDocument221 pagesAbinisio GDE HelpvenkatesanmuraliPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijimekko To Nakimushi-Kun (The Bully and The Crybaby) MangaDocument1 pageIjimekko To Nakimushi-Kun (The Bully and The Crybaby) MangaNguyễn Thị Mai Khanh - MĐC - 11A22Pas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court rules stabilization fees not trust fundsDocument8 pagesSupreme Court rules stabilization fees not trust fundsNadzlah BandilaPas encore d'évaluation

- S2 Retake Practice Exam PDFDocument3 pagesS2 Retake Practice Exam PDFWinnie MeiPas encore d'évaluation

- THE PEOPLE OF FARSCAPEDocument29 pagesTHE PEOPLE OF FARSCAPEedemaitrePas encore d'évaluation

- Test Bank For Core Concepts of Accounting Information Systems 14th by SimkinDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Core Concepts of Accounting Information Systems 14th by Simkinpufffalcated25x9ld100% (46)

- IELTS Vocabulary ExpectationDocument3 pagesIELTS Vocabulary ExpectationPham Ba DatPas encore d'évaluation

- WassiDocument12 pagesWassiwaseem0808Pas encore d'évaluation

- Course Tutorial ASP - Net TrainingDocument67 pagesCourse Tutorial ASP - Net Traininglanka.rkPas encore d'évaluation

- Tygon S3 E-3603: The Only Choice For Phthalate-Free Flexible TubingDocument4 pagesTygon S3 E-3603: The Only Choice For Phthalate-Free Flexible TubingAluizioPas encore d'évaluation

- Symmetry (Planes Of)Document37 pagesSymmetry (Planes Of)carolinethami13Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ks3 Science 2008 Level 5 7 Paper 1Document28 pagesKs3 Science 2008 Level 5 7 Paper 1Saima Usman - 41700/TCHR/MGBPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Dec2021-AWS Command Line Interface - User GuideDocument215 pages5 Dec2021-AWS Command Line Interface - User GuideshikhaxohebkhanPas encore d'évaluation

- A General Guide To Camera Trapping Large Mammals in Tropical Rainforests With Particula PDFDocument37 pagesA General Guide To Camera Trapping Large Mammals in Tropical Rainforests With Particula PDFDiego JesusPas encore d'évaluation

- May, 2013Document10 pagesMay, 2013Jakob Maier100% (1)

- Ca. Rajani Mathur: 09718286332, EmailDocument2 pagesCa. Rajani Mathur: 09718286332, EmailSanket KohliPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection Paper #1 - Introduction To Action ResearchDocument1 pageReflection Paper #1 - Introduction To Action Researchronan.villagonzaloPas encore d'évaluation

- PREMIUM BINS, CARDS & STUFFDocument4 pagesPREMIUM BINS, CARDS & STUFFSubodh Ghule100% (1)

- Employee Engagement A Case Study at IVRCL-1Document7 pagesEmployee Engagement A Case Study at IVRCL-1Anonymous dozzql7znKPas encore d'évaluation

- Equipment, Preparation and TerminologyDocument4 pagesEquipment, Preparation and TerminologyHeidi SeversonPas encore d'évaluation

- sl2018 667 PDFDocument8 pagessl2018 667 PDFGaurav MaithilPas encore d'évaluation

- NetsimDocument18 pagesNetsimArpitha HsPas encore d'évaluation

- Your Inquiry EPALISPM Euro PalletsDocument3 pagesYour Inquiry EPALISPM Euro PalletsChristopher EvansPas encore d'évaluation

- Jazan Refinery and Terminal ProjectDocument3 pagesJazan Refinery and Terminal ProjectkhsaeedPas encore d'évaluation

- Antiquity: Middle AgesDocument6 pagesAntiquity: Middle AgesPABLO DIAZPas encore d'évaluation

- Machine Spindle Noses: 6 Bison - Bial S. ADocument2 pagesMachine Spindle Noses: 6 Bison - Bial S. AshanehatfieldPas encore d'évaluation

- Report Daftar Penerima Kuota Telkomsel Dan Indosat 2021 FSEIDocument26 pagesReport Daftar Penerima Kuota Telkomsel Dan Indosat 2021 FSEIHafizh ZuhdaPas encore d'évaluation