Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

SALES Case Digest

Transféré par

Onat PCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

SALES Case Digest

Transféré par

Onat PDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

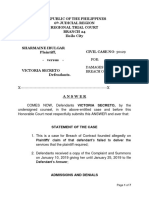

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

SUBJECT MATTER OF SALE

1. MELLIZA vs CITY OF ILOILO (23 SCRA 477)

Facts: Juliana Melliza during her lifetime owned, among

other properties, 3 parcels of residential land in Iloilo City

(OCT 3462).Said parcels of land were known as Lots Nos. 2,

5 and 1214. The total area of Lot 1214 was 29,073 sq. m. On

27 November 1931she donated to the then Municipality of

Iloilo, 9,000 sq. m. of Lot 1214, to serve as site for the

municipal hall. The donation was however revoked by the

parties for the reason that the area donated was found

inadequate to meet the requirements of the development

plan of the municipality, the so-called Arellano Plan.

Subsequently, Lot 1214 was divided by Certeza Surveying

Co., Inc. into Lots 1214-A and 1214-B. And still later, Lot

1214-B was further divided into Lots 1214-B-1, Lot 1214-B-2

and Lot1214-B-3. As approved by the Bureau of Lands, Lot

1214-B-1, with 4,562 sq. m., became known as Lot 1214-B;

Lot 1214-B-2,with 6,653 sq. m., was designated as Lot 1214C; and Lot 1214-B-3, with 4,135 sq. m., became Lot 1214-D.

On 15 November1932, Juliana Melliza executed an

instrument without any caption providing for the absolute

sale involving all of lot 5, 7669 sq.m. of Lot 2 (sublots 2-B

and 2-C), and a portion of 10,788 sq. m. of Lot 1214 (sublots

1214-B2 and 1214-B3) in favor of the Municipal Government

of Iloilo for the sum of P6,422; these lots and portions being

the ones needed by the municipal government for the

construction of avenues, parks and City hall site according

the Arellano plan.

On 14 January 1938, Melliza sold her remaining interest in

Lot 1214 to Remedios Sian Villanueva (thereafter TCT

18178). Remedios in turn on 4 November1946 transferred

her rights to said portion of land to Pio Sian Melliza

(thereafter TCT 2492). Annotated at the back of Pio Sian

Mellizas title certificate was the following that a portion of

10,788 sq. m. of Lot 1214 now designated as Lots 1412-B-2

and1214-B-3 of the subdivision plan belongs to the

Municipality of Iloilo as per instrument dated 15 November

1932. On 24 August 1949 the City of Iloilo, which

succeeded to the Municipality of Iloilo, donated the city hall

site together with the building thereon, to the University of

the Philippines (Iloilo branch). The site donated consisted of

Lots 1214-B, 1214-C and 1214-D, with a total area of 15,350

sq. m., more or less. Sometime in 1952, the University of the

Philippines enclosed the site donated with a wire fence. Pio

Sian Melliza thereupon made representations, thru his

lawyer, with the city authorities for payment of the value of

the lot (Lot 1214-B). No recovery was obtained, because as

alleged by Pio Sian Melliza, the City did not have funds. The

University of the Philippines, meanwhile, obtained Transfer

Certificate of Title No. 7152 covering the three lots, Nos.

1214-B,1214-C and 1214-D.On 10 December 1955 Pio Sian

Melizza filed an action in the CFI Iloilo against Iloilo City and

the University of the Philippines for recovery of Lot 1214-B

or of its value. After stipulation of facts and trial, the CFI

rendered its decision on 15 August 1957, dismissing the

complaint. Said court ruled that the instrument executed by

Juliana Melliza in favor of Iloilo municipality included in the

conveyance Lot 1214-B, and thus it held that Iloilo City had

the right to donate Lot 1214-B to UP. Pio Sian Melliza

appealed to the Court of Appeals. On 19 May 1965, the CA

affirmed the interpretation of the CFI that the portion of Lot

1214 sold by Juliana Melliza was not limited to the 10,788

square meters specifically mentioned but included whatever

was needed for the construction of avenues, parks and the

city hall site. Nonetheless, it ordered the remand of the case

for reception of evidence to determine the area actually

taken by Iloilo City for the construction of avenues, parks

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

and for city hall site. Hence, the appeal by Pio San Melliza to

the Supreme Court.

One of his causes of action was that the contract of sale

executed between Melliza and the Mun. referred only to lots

1214-C and 1214-D and it is unwarranted to include lot

1214-B as being included under the description therein

because that would mean that the object of the contract of

sale would be indeterminate. One of the essential

requirements for a contract of sale is that it should have for

its object a determinate thing.

HELD: The paramount intention of the parties was to

provide Iloilo municipality with lots sufficient or adequate in

area for the construction of the Iloilo City hall site, with its

avenues and parks. For this matter, a previous donation for

this purpose between the same parties was revoked by

them, because of inadequacy of the area of the lot donated.

Said instrument described 4parcels of land by their lot

numbers and area; and then it goes on to further describe,

not only those lots already mentioned, but the lots object of

the sale, by stating that said lots were the ones needed for

the construction of the city hall site, avenues and parks

according to the Arellano plan. If the parties intended

merely to cover the specified lots (Lots 2, 5, 1214-C and

1214-D), there would scarcely have been any need for the

next paragraph, since these lots were already plainly and

very clearly described by their respective lot number and

areas. Said next paragraph does not really add to the clear

description that was already given to them in the previous

one. It is therefore the more reasonable interpretation to

view it as describing those other portions of land contiguous

to the lots that, by reference to the Arellano plan, will be

found needed for the purpose at hand, the construction of

the city hall site.

The requirement of the law that a sale must have for its

object a determinate thing, is fulfilled as long as, at the time

the contract is entered into, the object of the sale is capable

of being made determinate without the necessity of a new

or further agreement between the parties (Art. 1273, old

Civil Code; Art. 1460, New Civil Code). The specific mention

of some of the lots plus the statement that the lots object of

the sale are the ones needed for city hall site; avenues and

parks, according to the Arellano plan, sufficiently provides a

basis, as of the time of the execution of the contract, for

rendering determinate said lots without the need of a new

and further agreement of the parties.

The Supreme Court affirmed the decision appealed from

insofar as it affirms that of the CFI, and dismissed the

complaint; without costs

2. YU TEK vs GONZALES (29 Phil 384)

FACTS: A written contract was executed between Basilio

Gonzalez and Yu Tek and Co., where Gonzales was obligated

to deliver600 piculs of sugar of the 1st and 2nd grade to Yu

Tek, within the period of 3 months (1 January-31 March

1912) at any place within the municipality of Sta. Rosa,

which Yu Tek & Co. or its representative may designate; and

in case, Gonzales does not deliver, the contract will be

rescinded and Gonzales shall be obligated to return the

P3,000 received and also the sum of P1,200by way of

indemnity for loss and damages. No sugar had been

delivered to Yu Tek & Co. under this contract nor had it been

able to recover the P3,000. Yu Tek & Co. filed a complaint

against Gonzales, and prayed for judgment for the P3,000

and the additional P1,200. Judgment was rendered for

P3,000 only, and from this judgment both parties appealed.

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

Defendant alleges that the court erred in refusing to permit

parol evidence showing that the parties intended that the

sugar was to be secured from the crop which the defendant

raised on his plantation, and that he was unable to fulfill the

contract by reason of the almost total failure of his crop.

The second contention of the defendant arises from the first.

He assumes that the contract was limited to the sugar he

might raise upon his own plantation; that the contract

represented a perfected sale; and that by failure of his crop

he was relieved from complying with his undertaking by loss

of the thing due. (Arts. 1452, 1096, and 1182, Civil Code.)

ISSUES: 1) Whether compliance of the obligation to deliver

depends upon the production in defendants plantation

2) Whether there is a perfected sale

3) Whether liquidated damages of P1,200 should be

awarded to the plaintif

HELD: 1) The case appears to be one to which the rule

which excludes parol evidence to add to or vary the terms of

a written contract is decidedly applicable. There is not the

slightest intimation in the contract that the sugar was to be

raised by the defendant. Parties are presumed to have

reduced to writing all the essential conditions of their

contract. While parol evidence is admissible in a variety of

ways to explain the meaning of written contracts, it cannot

serve the purpose of incorporating into the contract

additional contemporaneous conditions which are not

mentioned at all in the writing, unless there has been fraud

or mistake. It may be true that defendant owned a

plantation and expected to raise the sugar himself, but he

did not limit his obligation to his own crop of sugar. Our

conclusion is that the condition which the defendant seeks

to add to the contract by parol evidence cannot be

considered. The rights of the parties must be determined by

the writing itself.

2) Article 1450 defines a perfected sale as follows: The sale

shall be perfected between vendor and vendee and shall be

binding on both of them, if they have agreed upon the thing

which is the object of the contract and upon the price, even

when neither has been delivered. Article 1452 provides

that the injury to or the profit of the thing sold shall, after

the contract has been perfected, be governed by the

provisions of articles 1096 and 1182. There is a perfected

sale with regard to the thing whenever the article of sale

has been physically segregated from all other articles

In McCullough vs. Aenlle & Co. (3 Phil 285), a particular

tobacco factory with its contents was held sold under a

contract which did not provide for either delivery of the

price or of the thing until a future time. In Barretto vs. Santa

Marina (26 Phil 200),specified shares of stock in a tobacco

factory were held sold by a contract which deferred delivery

of both the price and the stock until the latter had been

appraised by an inventory of the entire assets of the

company. In Borromeo vs. Franco (5 Phil.Rep., 49) a sale of a

specific house was held perfected between the vendor and

vendee, although the delivery of the price was withheld until

the necessary documents of ownership were prepared by

the vendee. In Tan Leonco vs. Go Inqui (8 Phil. Rep.,531) the

plaintif had delivered a quantity of hemp into the

warehouse of the defendant. The defendant drew a bill of

exchange in the sum of P800, representing the price which

had been agreed upon for the hemp thus delivered. Prior to

the presentation of the bill for payment, in said case, the

hemp was destroyed. Whereupon, the defendant suspended

payment of the bill. It was held that the hemp having been

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

already delivered, the title had passed and the loss was the

vendees. It is our purpose to distinguish the case at bar

from all these cases.

The contract in the present case was merely an executory

agreement; a promise of sale and not a sale. As there was

no perfected sale, it is clear that articles 1452, 1096, and

1182 are not applicable. The agreement upon the thing

which was the object of the contract was not within the

meaning of article 1450. Sugar is one of the staple

commodities of this country. For the purpose of sale its bulk

is weighed, the customary unit of weight being denominated

a picul.' There was no delivery under the contract. If called

upon to designate the article sold, it is clear that Gonzales

could only say that it was sugar. He could only use this

generic name for the thing sold. There was no

appropriation of any particular lot of sugar. Neither party

could point to any specific quantity of sugar.

The contract in the present case is diferent from the

contracts discussed in the cases referred to. In the

McCullough case, for instance, the tobacco factory which the

parties dealt with was specifically pointed out and

distinguished from all other tobacco factories. So, in the

Barretto case, the particular shares of stock which the

parties desired to transfer were capable of designation. In

the Tan Leonco case, where a quantity of hemp was the

subject of the contract, it was shown that quantity had been

deposited in a specific warehouse, and thus set apart and

distinguished from all other hemp

The Supreme Court affirmed the judgment appealed from

with the modification allowing the recovery of P1,200 under

paragraph 4 of the contract, without costs

3. NATONAL GRAINS AUTHORITY vs IAC

FACTS: National Grains Authority (now National Food

Authority, NFA) is a government agency created under PD 4.

One of its incidental functions is the buying of palay grains

from qualified farmers. On 23 August 1979, Leon Soriano

ofered to sell palay grains to the NFA, through the Provincial

Manager (William Cabal) of NFA in Tuguegarao, Cagayan. He

submitted the documents required by the NFA for prequalifying as a seller, which were processed and

accordingly, he was given a quota of 2,640 cavans of palay.

The quota noted in the Farmers Information Sheet

represented the maximum number of cavans of palay that

Soriano may sell to the NFA. On 23 and 24 August 1979,

Soriano delivered 630 cavans of palay. The palay delivered

were not rebagged, classified and weighed. When Soriano

demanded payment of the 630 cavans of palay, he was

informed that its payment will beheld in abeyance since Mr.

Cabal was still investigating on an information he received

that Soriano was not a bona fide farmer and the palay

delivered by him was not produced from his farmland but

was taken from the warehouse of a rice trader, Ben de

Guzman. On 28 August 1979, Cabal wrote Soriano advising

him to withdraw from the NFA warehouse the 630 cavans

stating that NFA cannot legally accept the said delivery on

the basis of the subsequent certification of the BAEX

technician (Napoleon Callangan) that Soriano is not a bona

fide farmer.

Instead of withdrawing the 630 cavans of palay, Soriano

insisted that the palay grains delivered be paid. He then

filed a complaint for specific performance and/or collection

of money with damages on 2 November 1979, against the

NFA and William Cabal (Civil Case 2754). Meanwhile, by

agreement of the parties and upon order of the trial court,

the 630 cavans of palay in question were withdrawn from

the warehouse of NFA. On 30 September 1982, the trial

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

court found Soriano a bona fide farmer and rendered

judgment ordering the NFA, its officers and agents to pay

Soriano the amount of P47,250.00 representing the unpaid

price of the 630 cavans of palay plus legal interest thereof

(12% per annum, from the filing of complaint on 20

November1979 until fully paid). NFA and Cabal filed a

motion for reconsideration, which was denied by the court

on 6 December 1982.Appeal was filed with the Intermediate

Appellate Court. On 23 December 1986, the then IAC upheld

the findings of the trialc ourt and affirmed the decision

ordering NFA and its officers to pay Soriano the price of the

630 cavans of rice plus interest. Themotion for

reconsideration of the appellate courts decision was denied

in a resolution dated 17 April 1986. Hence, the present

petition for review with the sole issue of whether or not

there was a contract of sale in the present case.

ISSUE: Whether there was a perfected sale

HELD: Soriano initially ofered to sell palay grains produced

in his farmland to NFA. When the latter accepted the ofer by

noting in Soriano's Farmer's Information Sheet a quota of

2,640 cavans, there was already a meeting of the minds

between the parties. The object of the contract, being the

palay grains produced in Soriano's farmland and the NFA

was to pay the same depending upon its quality.

The fact that the exact number of cavans of palay to be

delivered has not been determined does not afect the

perfection of the contract. Article 1349 of the New Civil Code

provides: ".The fact that the quantity is not determinate

shall not be an obstacle to the existence of the contract,

provided it is possible to determine the same, without the

need of a new contract between the parties." In this case,

there was no need for NFA and Soriano to enter into a new

contract to determine the exact number of cavans of palay

to be sold. Soriano can deliver so much of his produce as

long as it does not exceed 2,640 cavans. From the moment

the contract of sale is perfected, it is incumbent upon the

parties to comply with their mutual obligations or "the

parties may reciprocally demand performance" thereof.

The Supreme Court dismissed the instant petition for review,

and affirmed the assailed decision of the then IAC (now

Court of Appeals) is affirmed; without costs.

4. SCHUBACK & SONS vs. CA

FACTS: In 1981, Ramon San Jose (Philippine SJ Industrial

Trading) established contact with Johannes Schuback & Sons

Philippine Trading Corporation through the Philippine

Consulate General in Hamburg, West Germany, because he

wanted to purchase MAN bus spare parts from Germany.

Schuback communicated with its trading partner, Johannes

Schuback and Sohne Handelsgesellschaft m.b.n. & Co.

(Schuback Hamburg) regarding the spare parts San Jose

wanted to order. On 16 October 1981,San Jose submitted to

Schuback a list of the parts he wanted to purchase with

specific part numbers and description. Schuback referred

the list to Schuback Hamburg for quotations. Upon receipt of

the quotations, Schuback sent to San Jose a letter dated25

November 1981 enclosing its ofer on the items listed. On 4

December 1981, San Jose informed Schuback that he

preferred genuine to replacement parts, and requested that

he be given a 15% discount on all items. On 17 December

1981, Schuback submitted its formal ofer containing the

item number, quantity, part number, description, unit price

and total to San Jose. On24 December 1981, San Jose

informed Schuback of his desire to avail of the prices of the

parts at that time and enclosed its Purchase Order 0101

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

dated 14 December 1981. On 29 December 1981, San Jose

personally submitted the quantities he wanted to Mr. Dieter

Reichert, General Manager of Schuback, at the latters

residence. The quantities were written in ink by San Jose in

the same PO previously submitted. At the bottom of said PO,

San Jose wrote in ink above his signature: NOTE: Above PO

will include a 3% discount. The above will serve as our initial

PO. Schuback immediately ordered the items needed by

San Jose from Schuback Hamburg. Schuback Hamburg in

turn ordered the items from NDK, a supplier of MAN spare

parts in West Germany.

On 4 January 1982, Schuback Hamburg sent Schuback a

proforma invoice to be used by San Jose in applying for a

letter of credit. Said invoice required that the letter of credit

be opened in favor of Schuback Hamburg. San Jose

acknowledged receipt of the invoice. An order confirmation

was later sent by Schuback Hamburg to Schuback which

was forwarded to and received by San Jose on 3 February

1981. On 16 February 1982, Schuback reminded San Jose to

open the letter of credit to avoid delay in shipment and

payment of interest. In the meantime, Schuback Hamburg

received invoices from NDK for partial deliveries on Order

12204. On 16 February 1984, Schuback Hamburg paid NDK.

On 18 October 1982, Schuback again reminded San Jose of

his order and advised that the case may be endorsed to its

lawyers. San Jose replied that he did not make any valid PO

and that there was no definite contract between him and

Schuback. Schuback sent a rejoinder explaining that there is

a valid PO and suggesting that San Jose either proceed with

the order and open a letter of credit or cancel the order and

pay the cancellation fee of 30% F.O.B. value, or Schuback

will endorse the case to its lawyers. Schuback Hamburg

issued a Statement of Account to Schuback enclosing

therewith Debit Note charging Schuback 30% cancellation

fee, storage and interest charges in the total

amount of DM 51,917.81. Said amount was deducted from

Schubacks account with Schuback Hamburg. Demand

letters sent to San Jose by Schubacks counsel dated 22

March 1983 and 9J une 1983 were to no avail.

Schuback filed a complaint for recovery of actual or

compensatory damages, unearned profits, interest,

attorneys fees and costs against San Jose. In its decision

dated 13 June 1988, the trial court ruled in favor of

Schuback by ordering San Jose to pay it, among others,

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

actual compensatory damages in the amount of DM

51,917.81, unearned profits in the amount of DM14,061.07,

or their peso equivalent. San Jose elevated his case before

the Court of Appeals. On 18 February 1992, the appellate

court reversed the decision of the trial court and dismissed

Schubacks complaint. It ruled that there was no perfection

of contract since there was no meeting of the minds as to

the price between the last week of December 1981 and the

first week of January 1982. Hence, the petition for review on

certiorari.

ISSUE: Whether or not a contract of sale has been

perfected between the parties

HELD: Article 1319 of the Civil Code states: "Consent is

manifested by the meeting of the ofer and acceptance upon

the thing and the cause which are to constitute the contract.

The ofer must be certain and the acceptance absolute. A

qualified acceptance constitutes a counter ofer." The facts

presented to us indicate that consent on both sides has

been manifested. The ofer by petitioner was manifested on

December 17, 1981 when petitioner submitted its proposal

containing the item number, quantity, part number,

description, the unit price and total to private respondent.

On December 24, 1981, private respondent informed

petitioner of his desire to avail of the prices of the parts at

that time and simultaneously enclosed its Purchase Order.

At this stage, a meeting of the minds between vendor and

vendee has occurred, the object of the contract: being the

spare parts and the consideration, the price stated in

petitioner's ofer dated December 17, 1981 and accepted by

the respondent on December 24, 1981.

Although the quantity to be ordered was made determinate

only on 29 December 1981, quantity is immaterial in the

perfection of a sales contract. What is of importance is the

meeting of the minds as to the object and cause, which from

the facts disclosed, show that as of 24 December 1981,

these essential elements had already concurred. Thus,

perfection of the contract took place, not on 29 December

1981, but rather on 24 December 1981.

5. NOOL vs CA

FACTS: One lot formerly owned by Victorio Nool (TCT T74950) has an area of 1 hectare. Another lot previously

owned byF rancisco Nool (TCT T-100945) has an area of

3.0880 hectares. Both parcels are situated in San Manuel,

Isabela. Spouses Conchita Nool and Gaudencio Almojera

(plaintifs) alleged that they are the owners of the subject

land as they bought the same from Victorio and Francisco

Nool, and that as they are in dire need of money, they

obtained a loan from the Ilagan Branch of the DBP (Ilagan,

Isabela), secured by a real estate mortgage on said parcels

of land, which were still registered in the names of Victorino

and Francisco Nool, at the time, and for the failure of the

plaintifs to pay the said loan, including interest and

surcharges, totaling P56,000.00, the mortgage was

foreclosed; that within the period of redemption, the

plaintifs contacted Anacleto Nool for the latter to redeem

the foreclosed properties from DBP, which the latter did; and

as a result, the titles of the2 parcels of land in question were

transferred to Anacleto; that as part of their arrangement or

understanding, Anacleto agreed to buy from Conchita the 2

parcels of land under controversy, for a total price of

P100,000.00, P30,000.00 of which price was paid to

Conchita, and upon payment of the balance of P14,000.00,

the plaintifs were to regain possession of the 2 hectares of

land, which amounts spouses Anacleto Nool and Emilia

Nebre (defendants) failed to pay, and the same day the said

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

arrangement was made; another covenant was entered into

by the parties, whereby the defendants agreed to return to

plaintifs the lands in question, at anytime the latter have

the necessary amount; that latter asked the defendants to

return the same but despite the intervention of the

Barangay Captain of their place, defendants refused to

return the said parcels of land to plaintifs; thereby impelling

the plaintifs to come to court for relief. On the other hand,

defendants theorized that they acquired the lands in

question from the DBP, through negotiated sale, and were

misled by plaintifs when defendant Anacleto Nool signed

the private writing, agreeing to return subject lands when

plaintifs have the money to redeem the same; defendant

Anacleto having been made to believe, then, that his sister,

Conchita, still had the right to redeem the said properties

It should be stressed that Manuel S. Mallorca, authorized

officer of DBP, certified that the 1-year redemption period

(from 16March 1982 up to 15 March 1983) and that the

mortgagors right of redemption was not exercised within

this period. Hence, DBP became the absolute owner of said

parcels of land for which it was issued new certificates of

title, both entered on 23 May1983 by the Registry of Deeds

for the Province of Isabela. About 2 years thereafter, on 1

April 1985, DBP entered into a Deed of Conditional Sale

involving the same parcels of land with Anacleto Nool as

vendee. Subsequently, the latter was issued new certificates

of title on 8 February 1988.

The trial court ruled in favor of the defendants, declaring the

private writing to be an option to sell, not binding and

considered validly withdrawn by the defendants for want of

consideration; ordering the plaintifs to return to the

defendants the sum of P30,000.00 plus interest thereon at

the legal rate, from the time of filing of defendants

counterclaim until the same is fully paid; to deliver peaceful

possession of the 2 hectares; and to pay reasonable rents on

said 2 hectares at P5,000.00 per annum or at P2,500.00 per

cropping from the time of judicial demand until the said lots

shall have been delivered to the defendants; and to pay the

costs. The plaintifs appealed to the Court of Appeals (CA GR

CV 36473), which affirmed the appealed judgment intoto on

20 January 1993. Hence, the petition before the Supreme

Court.

ISSUE: Whether the Contract of Repurchase is valid.

HELD: Nono dat quod non habet, No one can give

what he does not have; Contract of repurchase

inoperative thus void.

A contract of repurchase arising out of a contract of sale

where the seller did not have any title to the property sold

is not valid. Since nothing was sold, then there is also

nothing to repurchase.

Article 1505 of the Civil Code provides that where goods

are sold by a person who is not the owner thereof, and who

does not sell them under authority or with consent of the

owner, the buyer acquires no better title to the goods than

the seller had, unless the owner of the goods is by his

conduct precluded from denying the sellers authority to

sell. Jurisprudence, on the other hand, teaches us that a

person can sell only what he owns or is authorized to sell;

the buyer can as a consequence acquire no more than what

the seller can legally transfer. No one can give what he

does not have nono dat quod non habet.

In the present case, there is no allegation at all that

petitioners were authorized by DBP to sell the property to

the private respondents. Further, the contract of repurchase

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

that the parties entered into presupposes that petitioners

could repurchase the property that they sold to private

respondents. As petitioners sold nothing, it follows that

they can also repurchase nothing. In this light, the

contract of repurchase is also inoperative and by the same

analogy, void.

The Supreme Court denied the petition, and affirmed the

assailed decision of the Court of Appeals

6. VILLAFLOR vs CA

FACTS: On 16 January 1940, Cirilo Piencenaves, in a Deed

of Absolute Sale, sold to Vicente Villafor, a parcel of

agricultural land (planted to Abaca) containing an area of 50

hectares, more or less. The deed states that the land was

sold to Villaflor on 22 June1937, but no formal document

was then executed, and since then until the present time,

Villaflor has been in possession and occupation of the same.

Before the sale of said property, Piencenaves inherited said

property form his parents and was in adverse possession of

such without interruption for more than 50 years. On the

same day, Claudio Otero, in a Deed of Absolute Sale sold to

Villaflor a parcel of agricultural land (planted to corn),

containing an area of 24 hectares, more or less;

Hermogenes Patete, in a Deed of Absolute Sale sold to

Villaflor, a parcel of agricultural land (planted to abaca and

corn), containing an area of 20 hectares, more or less. Both

deed state the same details or circumstances as that of

Piencenaves. On 15 February 1940, Fermin Bocobo, in a

Deed of Absolute Sale sold to Villaflor, a parcel of

agricultural land (planted with abaca), containing an area of

18 hectares, more or less.

On 8 November 1946, Villaflor leased to Nasipit Lumber Co.,

Inc. a parcel of land, containing an area of 2 hectares,

together with all the improvements existing thereon, for a

period of 5 years (from 1 June 1946) at a rental of P200.00

per annum to cover the annual rental of house and building

sites for 33 houses or buildings. The lease agreement

allowed the lessee to sublease the premises to any person,

firm or corporation; and to build and construct additional

houses with the condition the lessee shall pay to the lessor

the amount of 50 centavos per month for every house and

building; provided that said constructions and improvements

become the property of the lessor at the end of the lease

without obligation on the part of the latter for expenses

incurred in the construction of the same.

On 7 July 1948, in an Agreement to Sell Villaflor conveyed

to Nasipit Lumber, 2 parcels of land. Parcel 1 contains an

area of 112,000 hectares more or less, divided into lots

5412, 5413, 5488, 5490,5491, 5492, 5850, 5849, 5860,

5855, 5851, 5854, 5855, 5859, 5858, 5857, 5853, and 5852;

and containing abaca, fruit trees, coconuts and thirty houses

of mixed materials belonging to the Nasipit Lumber

Company. Parcel 2 contains an area of 48,000more or less,

divided into lots 5411, 5410, 5409, and 5399, and

containing 100 coconut trees, productive, and 300 cacao

trees. From said day, the parties agreed that Nasipit Lumber

shall continue to occupy the property not anymore in

concept of lessee but as prospective owners.

On 2 December 1948, Villaflor filed Sales Application V-807

with the Bureau of Lands, Manila, to purchase under the

provisions of Chapter V, XI or IX of CA 141 (The Public Lands

Act), as amended, the tract of public lands. Paragraph 6 of

the Application, states: I understand that this application

conveys no right to occupy the land prior to its approval,

and I recognize that the land covered by the same is of

public domain and any and all rights I may have with

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

respect thereto by virtue of continuous occupation and

cultivation are hereby relinquished to the Government.

On 7 December 1948, Villaflor and Nasipit Lumber executed

an Agreement, confirming the Agreement to Sell of 7 July

1948, but with reference to the Sales Application filed with

the Bureau of Land. On 31 December 1949, the Report by

the public land inspector (District Land Office, Bureau of

Lands, in Butuan) contained an endorsement of the said

officer recommending rejection of the Sales Application of

Villaflor for having leased the property to another even

before he had acquired transmissible rights thereto. In a

letter of Villaflor dated 23 January1950, addressed to the

Bureau of Lands, he informed the Bureau Director that he

was already occupying the property when the Bureaus

Agusan River Valley Subdivision Project was inaugurated,

that the property was formerly claimed as private property,

and that therefore, the property was segregated or excluded

from disposition because of the claim of private ownership.

Likewise, in a letter of Nasipit Lumber dated 22 February

1950 addressed to the Director of Lands, the corporation

informed the Bureau that it recognized Villaflor as the real

owner, claimant and occupant of the land; that since June

1946, Villaflor leased 2hectares inside the land to the

company; that it has no other interest on the land; and that

the Sales Application of Villaflor should be given favorable

consideration.

On 24 July 1950, the scheduled date of auction of the

property covered by the Sales Application, Nasipit Lumber

ofered the highest bid of P41.00 per hectare, but since an

applicant under CA 141, is allowed to equal the bid of the

highest bidder, Villaflor tendered an equal bid, deposited the

equivalent of 10% of the bid price and then paid the

assessment in full.

10

On 16 August 1950, Villaflor executed a document,

denominated as a Deed of Relinquishment of Rights, in

favor on Nasipit Lumber, in consideration of the amount of

P5,000 that was to be reimbursed to the former

representing part of the purchase price of the land, the

value of the improvements Villaflor introduced thereon, and

the expenses incurred in the publication of the Notice of

Sale; in light of his difficulty to develop the same as Villaflor

has moved to Manila. Pursuant thereto, on 16 August1950,

Nasipit Lumber filed a Sales Application over the 2 parcels of

land, covering an area of 140 hectares, more or less. This

application was also numbered V-807. On 17 August 1950

the Director of Lands issued an Order of Award in favor of

Nasipit Lumber; and its application was entered in the

record as Sales Entry V-407.On 27 November 1973, Villafor

wrote a letter to Nasipit Lumber, reminding the latter of

their verbal agreement in 1955; but the new set of

corporate officers refused to recognize Villaflors claim.

In a formal protest dated 31 January 1974 which Villaflor

filed with the Bureau of Lands, he protested the Sales

Application of Nasipit Lumber, claiming that the company

has not paid him P5,000.00 as provided in the Deed of

Relinquishment of Rights dated 16 August 1950. On 8

August 1977, the Director of Lands found that the payment

of the amount of P5,000.00 in the Deed and the

consideration in the Agreement to Sell were duly proven,

and ordered the dismissal of Villaflors protest.

On 6 July 1978, Villaflor filed a complaint in the trial court

for Declaration of Nullity of Contract (Deed of

Relinquishment of Rights), Recovery of Possession (of two

parcels of land subject of the contract), and Damages at

about the same time that he appealed the decision of the

Minister of Natural Resources to the Office of the President.

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

On 28 January 1983, he died. The trial court ordered his

widow, Lourdes D. Villaflor, to be substituted as petitioner.

After trial in due course, the then CFI Agusan del Norte and

Butuan City, Branch III, dismissed the complaint on the

grounds that: (1) petitioner admitted the due execution and

genuineness of the contract and was estopped from proving

its nullity, (2) the verbal lease agreements were

unenforceable under Article 1403 (2)(e) of the Civil Code,

and (3) his causes of action were barred by extinctive

prescription and/or laches. It ruled that there was

prescription and/or laches because the alleged verbal lease

ended in 1966, but the action was filed only on 6 January

1978. The 6-year period within which to file an action on an

oral contract per Article 1145 (1) of the Civil Code expired in

1972. Nasipit Lumber was declared the lawful owner and

actual physical possessor of the 2 parcels of land

(containing a total area of 160 hectares). The Agreements to

Sell Real Rights and the Deed of Relinquishment of Rights

over the 2 parcels were likewise declared binding between

the parties, their successors and assigns; with double costs

against Villaflor. The heirs of petitioner appealed to the

Court of Appeals which, however, rendered judgment

against them via the assailed Decision dated 27 September

1990 finding petitioners prayers (1) for the declaration of

nullity of the deed of relinquishment, (2) for the eviction of

private respondent from the property and (3) for the

declaration of petitioners heirs as owners to be without

basis.

Not satisfied, petitioners heirs filed the petition for review

dated 7 December 1990. In a Resolution dated 23 June

1991, the Court denied this petition for being late. On

reconsideration, the Court reinstated the petition.

11

ISSUE: Whether the sale is valid or void for the alleged

existence of simulation of contract

HELD: The provision of the law is specific that public lands

can only be acquired in the manner provided for therein and

not otherwise(Sec. 11, CA. No. 141, as amended). In his

sales application, petitioner expressly admitted that said

property was public land. This is formidable evidence as it

amounts to an admission against interest. The records show

that Villaflor had applied for the purchase of lands in

question with this Office (Sales Application V-807) on 2

December 948. There is a condition in the sales application

to the efect that he recognizes that the land covered by the

same is of public domain and any and all rights he may have

with respect thereto by virtue of continuous occupation and

cultivation are relinquished to the Government of which

Villaflor is very much aware. It also appears that Villaflor had

paid for the publication fees appurtenant to the sale of the

land. He participated in the public auction where he was

declared the successful bidder. He had fully paid the

purchase price thereof. It would be a height of absurdity for

Villaflor to be buying that which is owned by him if his claim

of private ownership thereof is to be believed. The area in

dispute is not the private property of the petitioner.

It is a basic assumption of public policy that lands of

whatever classification belong to the state. Unless alienated

in accordance with law, it retains its rights over the same as

dominus. No public land can be acquired by private persons

without any grant, express or implied from the government.

It is indispensable then that there be showing of title from

the state or any other mode of acquisition recognized by

law. s such sales applicant manifestly acknowledged that he

does not own the land and that the same is a public land

under the administration of the Bureau of Lands, to which

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

the application was submitted, all of its acts prior thereof,

including its real estate tax declarations, characterized its

possessions of the land as that of a sales applicant. And

consequently, as one who expects to buy it, but has not as

yet done so, and is not, therefore, its owner.

The rule on the interpretation of contracts (Article 1371) is

used in affirming, not negating, their validity. Article 1373,

which is a conjunct of Article 1371, provides that, if the

instrument is susceptible of two or more interpretations, the

interpretation which will make it valid and efectual should

be adopted. In this light, it is not difficult to understand that

the legal basis urged by petitioner does not support his

allegation that the contracts to sell and the deed of

relinquishment are simulated and fictitious.

Simulation occurs when an apparent contract is a

declaration of a fictitious will, deliberately made by

agreement of the parties, in order to produce, for the

purpose of deception, the appearance of a juridical act

which does not exist or is diferent from that which was

really executed. Such an intention is not apparent in the

agreements. The intent to sell, on the other hand, is as clear

as daylight. The fact, that the agreement to sell (7

December 1948) did not absolutely transfer ownership of

the land to private respondent, does not show that the

agreement was simulated. Petitioners delivery of the

Certificate of Ownership and execution of the deed of

absolute sale were suspensive conditions, which gave rise to

a corresponding obligation on the part of the private

respondent, i.e., the payment of the last installment of the

consideration mentioned in the Agreement. Such conditions

did not afect the perfection of the contract or prove

simulation

12

Nonpayment, at most, gives the vendor only the right to sue

for collection. Generally, in a contract of sale, payment of

the price is a resolutory condition and the remedy of the

seller is to exact fulfillment or, in case of a substantial

breach, to rescind the contract under Article 1191 of the

Civil Code. However, failure to pay is not even a breach, but

merely an event which prevents the vendors obligation to

convey title from acquiring binding force.

T he requirements for a sales application under the Public

Land Act are: (1) the possession of the qualifications

required by said Act (under Section 29) and (2) the lack of

the disqualifications mentioned therein (under Sections 121,

122, and 123). Section121 of the Act pertains to acquisitions

of public land by a corporation from a grantee: The private

respondent, not the petitioner, was the direct grantee of the

disputed land. Sections 122 and 123 disqualify corporations,

which are not authorized by their charter, from acquiring

public land; the records do not show that private respondent

was not so authorized under its charter

The Supreme Court dismissed the petition.

PRICE

7. LOYOLA vs CA

FACTS: A parcel of land (Lot 115-A-1 of subdivision plan

[LRC] Psd-32117, a portion of Lot 115-A described on Plan

Psd-55228, LRC[GLRO] Record 8374, located in Poblacion,

Binan, Laguna, and containing 753 sq.m., TCT T-32007) was

originally owned in common by the siblings Mariano and

Gaudencia Zarraga, who inherited it from their father.

Mariano predeceased his sister who died single, without

ofspring on 5 August 1983, at the age of 97. Victorina

Zarraga vda. de Loyola and Cecilia Zarraga, are sisters of

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

Gaudencia and Mariano. The property was subject of Civil

Case B-1094 before the then CFI Laguna (Branch 1, Spouses

Romualdo Zarraga, et al. v .Gaudencia Zarraga, et al.).

Romualdo Zarraga was the plaintif in Civil Case B-1094. The

defendants were his siblings: Nieves, Romana, Guillermo,

Purificacion, Angeles, Roberto, Estrella, and Jose, all

surnamed Zarraga, as well as his aunt, Gaudencia. The trial

court decided Civil Case B-1094 in favor of the defendants.

Gaudencia was adjudged owner of the 1/2 portion of Lot

115-A-1. Romualdo elevated the decision to the Court of

Appeals and later the Supreme Court. The petition (GR

59529) was denied by the Court on 17 March 1982.On 24

August 1980, nearly 3 years before the death of Gaudencia

while GR 59529 was still pending before the Supreme Court.

On said date, Gaudencia allegedly sold to the children of

Mariano Zarraga (Nieves, Romana, Romualdo, Guillermo,

Lucia, Purificacion, Angeles, Roberto, Estrella Zarraga) and

the heirs of Jose Zarraga Aurora, Marita, Jose, Ronaldo,

Victor, Lauriano,and Ariel Zarraga; first cousins of the

Loyolas) her share in Lot 115-A- 1 for P34,000.00. The sale

was evidenced by a notarizeddocument denominated as

Bilihang Tuluyan ng Kalahati (1/2) ng Isang Lagay na Lupa.

Romualdo, the petitioner in GR 59529, was among the

vendees.The decision in Civil Case B-1094 became final. The

children of Mariano Zarraga and the heirs of Jose Zarraga

(privaterespondents) filed a motion for execution.

On 16 February 1984, the sherif executed the

corresponding deed of reconveyance to Gaudencia. On 23

July 1984, however, the Register of Deeds of Laguna,

Calamba Branch, issued in favor of private respondents, TCT

T-116067, on the basis of the sale on 24 August 1980 by

Gaudencia to them. On 31 January 1985, Victorina and

Cecilia filed a complaint, docketed as Civil Case B-2194, with

13

the RTC of Bian, Laguna, for the purpose of annulling the

sale and the TCT. Victorina died on 18 October 1989, while

Civil Case B-2194 was pending with the trial court. Cecilia

died on 4 August 1990, unmarried and childless. Victorina

and Cecilia were substituted by Ruben, Candelaria,Lorenzo,

Flora, Nicadro, Rosario, Teresita and Vicente Loyola as

plaintifs. The trial court rendered judgment in favor of

complainants; declaring the simulated deed of absolute sale

as well as the issuance of the corresponding TCT null and

void, ordering the Register of Deeds of Laguna to cancel TCT

T-116087 and to issue another one in favor of the plaintifs

and the defendants as co-owners and legal heirs of the late

Gaudencia, ordering the defendants to reconvey and deliver

the possession of the shares of the plaintif on the subject

property, ordering the defendants to pay P20,000 as

attorneys fees and cost of suit, dismissing the petitioners

claim for moral and exemplary damages, and dismissing the

defendants counterclaim for lack of merit. On appeal, and

on 31 August 1993, the appellate court reversed the trial

court (CA-GR CV 36090). On September 15, 1993, the

petitioners (as substitute parties for Victorina and Cecilia,

the original plaintifs) filed a motion for reconsideration,

which was denied on 6 June 1994. Hence, the petition for

review on certiorari.

ISSUE: Whether the alleged sale between Gaudencia and

respondents is valid

HELD: Petitioners vigorously assail the validity of the

execution of the deed of absolute sale suggesting that since

the notary public who prepared and acknowledged the

questioned Bilihan did not personally know Gaudencia, the

execution of the deed was suspect. The rule is that a

notarized document carries the evidentiary weight conferred

upon it with respect to its due execution, and documents

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

acknowledged before a notary public have in their favor the

presumption of regularity. By their failure to overcome this

presumption, with clear and convincing evidence,

petitioners are estopped from questioning the regularity of

the execution of the deed.

in the deed of sale, was the one who questioned

Gaudencias ownership in Civil Case B-1094, Romana

testified that Romualdo really had no knowledge of the

transaction and he was included as a buyer of the land only

because he was a brother.

Petitioners suggest that all the circumstances lead to the

conclusion that the deed of sale was simulated. Simulation

is "the declaration of a fictitious will, deliberately made by

agreement of the parties, in order to produce, for the

purposes of deception, the appearances of a juridical act

which does not exist or is diferent what that which was

really executed." Characteristic of simulation is that the

apparent contract is not really desired or intended to

produce legal efect or in any way alter the juridical situation

of the parties. Perusal of the questioned deed will show that

the sale of the property would convert the co-owners to

vendors and vendees, a clear alteration of the juridical

relationships. This is contrary to the requisite of simulation

that the apparent contract was not really meant to produce

any legal efect. Also in a simulated contract, the parties

have no intention to be bound by the contract. But in this

case, the parties clearly intended to be bound by the

contract of sale, an intention they did not deny. The

requisites for simulation are: (a) an outward declaration of

will diferent from the will of the parties; (b) the false

appearance must have been intended by mutual

agreement; and (c) the purpose is to deceive third persons.

None of these are present in the assailed transaction.

Petitioners fault the Court of Appeals for not considering

that at the time of the sale in 1980, Gaudencia was already

94 years old; that she was already weak; that she was living

with private respondent Romana; and was dependent upon

the latter for her daily needs, such that under these

circumstances, fraud or undue influence was exercised by

Romana to obtain Gaudencia's consent to the sale. The rule

on fraud is that it is never presumed, but must be both

alleged and proved. For a contract to be annulled on the

ground of fraud, it must be shown that the vendor never

gave consent to its execution. If a competent person has

assented to a contract freely and fairly, said person is

bound. There also is a disputable presumption, that private

transactions have been fair and regular. Applied to

contracts, the presumption is in favor of validity and

regularity. In this case, the allegation of fraud was

unsupported, and the presumption stands that the contract

Gaudencia entered into was fair and regular.

Contracts are binding only upon the parties who execute

them. Article 1311 of the Civil Code clearly covers this

situation. In the present case Romualdo had no knowledge

of the sale, and thus, he was a stranger and not a party to it.

Even if curiously Romualdo, one of those included as buyer

14

Petitioners also claim that since Gaudencia was old and

senile, she was incapable of independent and clear

judgment. However, a person is not incapacitated to

contract merely because of advanced years or by reason of

physical infirmities. Only when such age or infirmities impair

his mental faculties to such extent as to prevent him from

properly, intelligently, and fairly protecting his property

rights, is he considered incapacitated. Petitioners show no

proof that Gaudencia had lost control of her mental faculties

at the time of the sale. The notary public who interviewed

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

her, testified that when he talked to Gaudencia before

preparing the deed of sale, she answered correctly and he

was convinced that Gaudencia was mentally fit and knew

what she was doing.

Petitioners seem to be unsure whether they are assailing the

sale of Lot 115-A-1 for being absolutely simulated or for

inadequacy of the price. These two grounds are

irreconcilable. If there exists an actual consideration for

transfer evidenced by the alleged act of sale, no matter how

inadequate it be, the transaction could not be a simulated

sale. No reversible error was thus committed by the Court

of Appeals in refusing to annul the questioned sale for

alleged inadequacy of the price

The Supreme Court denied the petition, and affirmed the

assailed decision of the Court of Appeals; with costs against

petitioners

8. UY vs CA

FACTS: William Uy and Rodel Roxas are agents authorized

to sell 8 parcels of land by the owners thereof. By virtue of

such authority, they ofered to sell the lands, located in

Tuba, Tadiangan, Benguet to National Housing Authority

(NHA) to be utilized and developed as a housing project. On

14 February 1989, the NHA Board passed Resolution 1632

approving the acquisition of said lands, with an area of

31.8231 hectares, at the cost of P23.867 million, pursuant to

which the parties executed a series of Deeds of Absolute

Sale covering the subject lands. Of the 8 parcels of land,

however, only 5 were paid for by the NHA because of the

report it received from the Land Geosciences Bureau of the

Department of Environment and Natural Resources

(DENR)that the remaining area is located at an active

15

landslide area and therefore, not suitable for development

into a housing project.

On 22 November 1991, the NHA issued Resolution 2352

cancelling the sale over the 3 parcels of land. The NHA,

through Resolution 2394, subsequently ofered the amount

of P1.225 million to the landowners as daos perjuicios. On

9 March 1992, petitioners Uy and Roxas filed before the RTC

Quezon City a Complaint for Damages against NHA and its

General Manager Robert Balao. After trial, the RTC rendered

a decision declaring the cancellation of the contract to be

justified. The trial court nevertheless awarded damages to

plaintifs in the sum of P1.255 million, the same amount

initially ofered by NHA to petitioners as damages.

Upon appeal by petitioners, the Court of Appeals reversed

the decision of the trial court and entered a new one

dismissing the complaint. It held that since there was

sufficient justifiable basis in cancelling the sale, it saw no

reason for the award of damages. The Court of Appeals also

noted that petitioners were mere attorneys-in-fact and,

therefore, not the real parties-in-interest in the action before

the trial court. Their motion for reconsideration having been

denied, petitioners seek relief from the Supreme Court.

ISSUES: 1) Whether the petitioners are real parties in

interest

2) Whether the cancellation is justified

HELD: 1) Section 2, Rule 3 of the Rules of Court requires

that every action must be prosecuted and defended in the

name of the real party-in-interest. The real party-in-interest

is the party who stands to be benefited or injured by the

judgment or the party entitled to the avails of the suit.

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

Interest, within the meaning of the rule, means material

interest, an interest in the issue and to be afected by the

decree, as distinguished from mere interest in the question

involved, or a mere incidental interest. Cases construing the

real party-in-interest provision can be more easily

understood if it is borne in mind that the true meaning of

real party-in-interest may be summarized as follows: An

action shall be prosecuted in the name of the party who, by

the substantive law, has the right sought to be enforced.

Where the action is brought by an attorney-in-fact of a land

owner in his name, (as in our present action) and not in the

name of his principal, the action was properly dismissed

because the rule is that every action must be prosecuted in

the name of the real parties-in-interest (Section 2, Rule 3,

Rules of Court)

Petitioners claim that they lodged the complaint not in

behalf of their principals but in their own name as agents

directly damaged by the termination of the contract.

Petitioners in this case purportedly brought the action for

damages in their own name and in their own behalf. An

action shall be prosecuted in the name of the party who, by

the substantive law, has the right sought to be enforced.

Petitioners are not parties to the contract of sale between

their principals and NHA. They are mere agents of the

owners of the land subject of the sale. As agents, they only

render some service or do something in representation or on

behalf of their principals. The rendering of such service did

not make them parties to the contracts of sale executed in

behalf of the latter. Since a contract may be violated only by

the parties thereto as against each other, the real parties-ininterest, either as plaintif or defendant, in an action upon

that contract must, generally, either be parties to said

contract. Petitioners have not shown that they are assignees

16

of their principals to the subject contracts. While they

alleged that they made advances and that they sufered loss

of commissions, they have not established any agreement

granting them "the right to receive payment and out of the

proceeds to reimburse [themselves] for advances and

commissions before turning the balance over to the

principal[s]."

2) The right of rescission or, more accurately, resolution, of

a party to an obligation under Article 1191 is predicated on

a breach of faith by the other party that violates the

reciprocity between them. The power to rescind, therefore,

is given to the injured party. Article 1191 states that the

power to rescind obligations is implied in reciprocal ones, in

case one of the obligors should not comply with what is

incumbent upon him. The injured party may choose

between the fulfillment and the rescission of the obligation,

with the payment of damages in either case. He may also

seek rescission, even after he has chosen fulfillment, if the

latter should become impossible. In the present case, the

NHA did not rescind the contract. Indeed, it did not have the

right to do so for the other parties to the contract, the

vendors, did not commit any breach, much less a substantial

breach, of their obligation. Their obligation was merely to

deliver the parcels of land to the NHA, an obligation that

they fulfilled. The NHA did not sufer any injury by the

performance thereof

The cancellation was not a rescission under Article 1191.

Rather, the cancellation was based on the negation of the

cause arising from the realization that the lands, which were

the object of the sale, were not suitable for housing. Cause

is the essential reason which moves the contracting parties

to enter into it. In other words, the cause is the immediate,

direct and proximate reason which justifies the creation of

COMPILATION OF CASE DIGESTS

an obligation through the will of the contracting parties.

Cause, which is the essential reason for the contract, should

be distinguished from motive, which is the particular reason

of a contracting party which does not afect the other party.

Ordinarily, a party's motives for entering into the contract

do not afect the contract. However, when the motive

predetermines the cause, the motive may be regarded as

the cause. In this case, it is clear, and petitioners do not

dispute, that NHA would not have entered into the contract

were the lands not suitable for housing. In other words, the

quality of the land was an implied condition for the NHA to

17

enter into the contract. On the part of the NHA, therefore,

the motive was the cause for its being a party to the sale.

We hold that the NHA was justified in canceling the contract.

The realization of the mistake as regards the quality of the

land resulted in the negation of the motive/cause thus

rendering the contract inexistent.

The Supreme Court denied the petition

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Release and Waiver of LiabilityDocument2 pagesRelease and Waiver of Liabilityapi-318687196Pas encore d'évaluation

- Victoria's Answer to Breach of Contract CaseDocument7 pagesVictoria's Answer to Breach of Contract CaseAnna Victoria Dela Vega100% (1)

- Bar Star Notes TaxationDocument3 pagesBar Star Notes TaxationOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- SS LAUNDRY Agreement Word FormatDocument3 pagesSS LAUNDRY Agreement Word FormatkkkkPas encore d'évaluation

- Elc 2009 - Study Pack FullDocument355 pagesElc 2009 - Study Pack FullAllisha BowenPas encore d'évaluation

- Rule 74 of The Revised Rules of CourtDocument4 pagesRule 74 of The Revised Rules of CourtDats FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Bar Exam Questionnaire on TaxationDocument3 pagesBar Exam Questionnaire on TaxationOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Labor Standards Finals Case DigestDocument130 pagesLabor Standards Finals Case Digestchacile100% (10)

- Mcle Judicial AffidavitDocument23 pagesMcle Judicial AffidavitJennilyn TugelidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tenancy AgreementDocument2 pagesTenancy AgreementKhushnood Ahmed Khan60% (5)

- Tax Q&ADocument4 pagesTax Q&AOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Diaz vs. CADocument2 pagesDiaz vs. CAMae NavarraPas encore d'évaluation

- Cusi vs. PNRDocument2 pagesCusi vs. PNRHoney Bunch67% (3)

- Jake's Place Current BrochureDocument20 pagesJake's Place Current BrochureRE/MAX Stephen Pahl TeamPas encore d'évaluation

- Grandchildren's rights to redeemed land under CARLDocument8 pagesGrandchildren's rights to redeemed land under CARLAngelo Vincent OmosPas encore d'évaluation

- Labor Secretary Authority in Alien EmploymentDocument2 pagesLabor Secretary Authority in Alien EmploymentElijahBactolPas encore d'évaluation

- Valles Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesValles Vs Comelectimothymarkmaderazo100% (1)

- Copyright Patent and TrademarkDocument18 pagesCopyright Patent and TrademarkOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Case DigestDocument22 pagesCase DigestOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Common Causes of Road AccidentsDocument2 pages5 Common Causes of Road AccidentsOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- PALS - Corporatioin CasesDocument7 pagesPALS - Corporatioin CasesOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Manulife control over insurance agent falls short of employment relationshipDocument304 pagesManulife control over insurance agent falls short of employment relationshipOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Case DigestDocument22 pagesCase DigestOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- PALS - Corporatioin CasesDocument7 pagesPALS - Corporatioin CasesOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Property Arts. 484-490Document8 pagesProperty Arts. 484-490Onat PPas encore d'évaluation

- PALS - Bar Ops Corporation Law Must Read CasesDocument70 pagesPALS - Bar Ops Corporation Law Must Read CasesOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Ownership To Co-OwnershipDocument179 pagesOwnership To Co-OwnershipOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Arts 414-426 Study GuideDocument3 pagesArts 414-426 Study GuideOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- CorpFinalExam TopicDocument73 pagesCorpFinalExam TopicOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Tax Pre WeekDocument1 page1 Tax Pre WeekOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- TaxDocument4 pagesTaxOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- ProvRem (Special Civil Actions)Document1 pageProvRem (Special Civil Actions)Onat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Pointers TaxDocument2 pagesPointers TaxOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Taxation BasicDocument4 pagesTaxation BasicOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Table of ContentsTax ExamDocument2 pagesTable of ContentsTax ExamOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- DocumentDocument1 pageDocumentOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Gan Tianco v. PabinguitDocument7 pagesGan Tianco v. PabinguitOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax HistoryDocument3 pagesTax HistoryOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Labor Review22112Document2 pagesLabor Review22112Onat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviewer Tax 1 Table of ContentDocument2 pagesReviewer Tax 1 Table of ContentOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Rodriguez v. MactalDocument7 pagesRodriguez v. MactalOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Art. 540-547 PropertyDocument10 pagesArt. 540-547 PropertyOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Kings Properties v. Galido Bad FaithDocument28 pagesKings Properties v. Galido Bad FaithOnat PPas encore d'évaluation

- Livingston County Foreclosed Property Tax AuctionDocument41 pagesLivingston County Foreclosed Property Tax AuctiondfksdksdjkljijiopwpaPas encore d'évaluation

- DPC Project 2019Document28 pagesDPC Project 2019Gaurav SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- A.C. No. 8761Document3 pagesA.C. No. 8761Fritch GamPas encore d'évaluation

- Padcom v. Ortigas CenterDocument11 pagesPadcom v. Ortigas CenterAiyla AnonasPas encore d'évaluation

- Doctrine of Stric Compliance PDFDocument16 pagesDoctrine of Stric Compliance PDFBM Ariful IslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Registration Cum Examination FormDocument1 pageRegistration Cum Examination FormWarda javedPas encore d'évaluation

- Manila Bay accretion disputeDocument24 pagesManila Bay accretion disputeRoman KushpatrovPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancillary ReliefDocument24 pagesAncillary ReliefAinnabila RosdiPas encore d'évaluation

- Prevention SuspensionDocument7 pagesPrevention SuspensionJha NizPas encore d'évaluation

- Cross-Charge: Borrowed & Lent and Inter-Company Processing in Oracle ProjectsDocument2 pagesCross-Charge: Borrowed & Lent and Inter-Company Processing in Oracle ProjectsSesirekha RavinuthulaPas encore d'évaluation

- Authorization To ExcludeDocument1 pageAuthorization To ExcludealphaformsPas encore d'évaluation

- Lawsuit Alleges Portland Teacher Hit Student, Used N-WordDocument4 pagesLawsuit Alleges Portland Teacher Hit Student, Used N-WordKGW News100% (1)

- Equipment Checkout ContractDocument1 pageEquipment Checkout ContractKaren Morgan VandiverPas encore d'évaluation

- OBLI Chapter 2 - Nature & EffectsDocument6 pagesOBLI Chapter 2 - Nature & EffectsGabby PundavelaPas encore d'évaluation

- WAIVER - For ECO PARK - Docx VER 2 5-26-17Document3 pagesWAIVER - For ECO PARK - Docx VER 2 5-26-17Jose Ignacio C CuerdoPas encore d'évaluation

- Quick Reference Guide For Travel AgentsDocument15 pagesQuick Reference Guide For Travel AgentsVamasPas encore d'évaluation

- PFR Law - Case DigestDocument49 pagesPFR Law - Case DigestReymart ReguaPas encore d'évaluation