Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

15 Political Events in Burma New or Recycled 2

Transféré par

Zaw Myo Aung0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

17 vues8 pages8 pgs

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce document8 pgs

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

17 vues8 pages15 Political Events in Burma New or Recycled 2

Transféré par

Zaw Myo Aung8 pgs

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 8

Burma

Briefing

Political Events in

Burma:

New or Recycled?

No. 15

September 2011

Introduction

Since November 2010 there have been a series

of political developments in Burma, many of

which have variously been hailed as new,

unprecedented and progress.

In August 2011 the slow drip of positive

developments became a steady stream, with a

number of initiatives which have gained positive

publicity for the dictatorship. While some remain

cautious, there is an increasing perception that

something new is happening in Burma.

Once again, many governments are arguing that

now is not the time to increase pressure for reform

or for an improvement in human rights. They argue

that we must wait and see what happens. Some

are even arguing for some existing measures to

be relaxed. This is despite the fact that on the

ground in Burma, the human rights situation has

deteriorated, most significantly with the increase

of rape and gang rape of ethnic minority women

committed by the Burmese Army.

The dictatorship in Burma has a long track record

of lying, and of dangling the prospect of impending

change to the international community, in order to

avoid increased pressure, or to try to get pressure

relaxed.

This briefing paper assesses whether events in

Burma in the past year really are new.

Are recent events in Burma a sign that real change

is on the way at last? Or is this more spin and

propaganda from the dictatorship, designed to relax

international pressure while maintaining their grip

on power?

The government has taken a number of

steps that has in my opinion the potential

for the improvement of human rights. The

problem is that we need to see concrete

actions from the government so that those

steps are translated into reality.

Tomas Ojea Quintana, UN Special

Rapporteur on Human Rights in Burma.

Key points:

Events taking place are not new.

So far no concrete steps have taken

place that give grounds for optimism.

No substantive reforms have taken place.

Human rights abuses are increasing.

Pressure should not be relaxed without

significant reform.

The dictatorship in Burma has a long

track record of lying.

Comment, briefing & analysis from Burma Campaign UK

New Elections in 2010

The first significant event was the election held

on 7th November 2010. To have an election

is not a new development in Burma. Elections

had previously been held in post independence

democratic Burma, and in 1974 Ne Win,

dictator at the time, also held a national vote for

representatives to a sham Parliament he had

created.

More recently, elections were held in 1990. While

the 1990 elections were not free or fair, the counting

of votes on the day was largely fair, and the National

League for Democracy (NLD) won 82 percent of

the seats. The results of the election were never

honoured, with the dictatorship refusing to hand

over power.

In the event, even those observers who had been

claiming the November 2010 elections would be

a major development, and some who had even

predicted they would be fair, were shocked by the

level of restrictions, unfair election rules and ballot

stuffing that took place. They swiftly retreated into

arguing that while these elections were not free and

fair, it was a step in the right direction, and perhaps

elections in five, ten, or fifteen years time would be

better.

Conditions were put in place to make it impossible

for the NLD to take part, including having to expel

more than 400 members jailed for their political

activities, and supporting a new constitution which

is designed to maintain dictatorship. The elections

had no credibility whatsoever. Despite this, great

attention has been paid to the powerless rubberstamp Parliament, where the military has a built in

veto.

Given the new Constitution, which maintains

dictatorship, and rules designed to prevent the NLD

from taking part in the election, severe restrictions

on parties and candidates, and mass ballot stuffing,

the elections cannot be seen as a credible and

significant new step towards democratisation.

The Release Of Aung San Suu Kyi

We hope that the decision to release Aung San

Suu Kyi has begun an irreversible process towards

democracy and economic reform, accompanied by

respect for human rights, which will lead to a closer

relationship between our two countries....We are

greatly encouraged by her unconditional return to

freedom and the atmosphere of conciliation in which

her release has taken place.

British Foreign Secretary Malcolm Rifkind, 11th

July 1995.

What I would like the world to realise is that the

elections and my release do not mean we have

reached some kind of turning point.

Aung San Suu Kyi, January 2011

The release of Aung San Suu Kyi on 13th November

2010 was a classic example of the masterful way

that the dictatorship manipulates the international

community. Aung San Suu Kyi should never have

been in detention in the first place, but by releasing

her they received international praise, and the

rigged elections held just six days before were

overshadowed. This is the third time that Aung

San Suu Kyi has been released from house arrest.

Experience has shown it is not a sign that there is a

process of political reform.

On 6th May 2002 coinciding with the release of

Aung San Suu Kyi, the dictatorship released a

statement that sounds eerily similar to that being

given to visiting diplomats today:

Today marks a new page for the people of

Myanmar and the international community. As we

look forward to a better future, we will work toward

greater international stability and improving the

social welfare of our diverse people.

A New President

Thein Sein may be new in his role as President, but

he is not a new figure. He has been in the top ranks

of the dictatorship since joining the State Peace and

Development Council in 1997. Prior to becoming

President, he had been appointed Prime Minister in

2007.

Thein Sein has variously been described as a

puppet for Than Shwe, or a moderate. In fact, he

is neither. Than Shwe doesnt need to pull Thein

Seins strings, Thein Sein has been in his inner

circle since at least 1992. Thein Sein is a true

believer, a trusted ally, hence his appointment. He

certainly has a different style and approach, but the

goals are the same, continued control of the country,

and crushing, controlling or co-opting opponents in

order to maintain that control.

Prime Minister General Thein Sein briefs Senior

General Than Shwe after Cyclone Nargis.

Again, having a new dictator in Burma is not new,

and does not in itself mean that political reforms and

democratisation is on the way. In fact, in Burma, the

opposite has been the case. Saw Maung and Than

Shwe could each be considered more brutal than

their predecessor.

Presidents Speech

On March 31st Thein Sein made a speech to

Parliament promising reforms, chiefly economic,

not political reforms. The fact that the speech got

so much attention was surprising in itself. Thein

Sein was on the ruling Council of the dictatorship

for 14 years. The track record of the dictatorship

in telling the truth during that time is amongst the

worst in the world. They have lied in media, lied at

international conferences, lied at the UN General

Assembly, and lied to successive UN envoys, even

when they knew those envoys were reporting back

to the UN Security Council. For example, after

his visit in November 2007, UN Envoy Ibrahim

Gambari faithfully reported back to the Security

Council regime promises to halt arrests and release

political prisoners. However, there were no releases,

and the arrests continued. Since early 2007

Thein Sein, as Prime Minister, has been the main

person responsible for telling lies on behalf of the

dictatorship. There has been speculation that his

experience and skill in dealing with the international

community was one of the reasons Than Shwe

picked him for the job.

Little attention was given to reasons Thein Sein

gave for needing economic reform, such as building

military might and that National Economy is

associated with political affairs. If the nation enjoys

economic growth, the people will become affluent,

and they will not be under the influence of internal

and external elements. In his own words, Thein

Seins stated motivation for economic change is

strengthening the military and consolidating power,

not tackling poverty.

Again it has been stated that for a President to

make such a speech promising reform is new.

Except it isnt. The previous dictator, Than Shwe,

also promised reforms, though without the high

profile rhetoric. In fact, in 1992, when he became

dictator, Than Shwe did more than just talk, he

admitted there were political prisoners, and released

more than 400 of them. This is in stark contrast to

Thein Seins regime, which denies political prisoners

even exist.

Khin Nyunt, head of military intelligence and later

Prime Minister under Than Shwe, also made regular

promises of reform, in public and in private.

The hypothesis being that the disgraced Prime

Minister was a moderate or a reformer who lost out

to the hard-liners in a power struggle ... General

Khin Nyunt was a hard-liner, albeit a more polished

and approachable one. He was a pragmatist

who cultivated foreign countries and a purported

dialogue with the opposition simply as a means to

mollify the international community and perpetuate

the regimes absolute control.

US cable from Rangoon August 2005, released

by Wikileaks.

Go back further and there are numerous examples

of Ne Win, Burmas first dictator, promising reforms,

often in similar grand speeches. Again, no genuine

reforms followed.

We have taken on heavy responsibilities, and we

shall continue to discharge them. Lack of knowhow may be a handicap for us, but we shall acquire

that know-how some day through trial and error.

But how people grumble and complain, and how

cunningly mischief-makers fan the fires. How long

will the transition last? they ask with sarcasm. Look

back, I would answer, look back across the years...

General Ne Win speech about economic reform,

1965.

New Parliament

Burmas new Parliament is powerless. This is not

just because the military have 25 percent of seats

reserved for them, giving them a veto power over

constitutional reform. Nor is because it is dominated

by representatives of the dictatorships party, the

Union Solidarity and Development Party, who are

there only because the elections were rigged. Nor

does its powerlessness stem from strict rules and

restrictions imposed on MPs. The Parliament is

constitutionally powerless. True power lies with

the President, the military, and the new National

Security and Defense Council, which replaced the

old State Peace and Development Council through

which the dictatorship used to rule Burma.

The first session of Parliament faced severe

restrictions, with no opportunity for serious debate,

and ministers refusing to answer some questions

posed by MPs, and some questions not even being

allowed to be asked.

In the second session there has been slightly more

debate. However, the significance attached to

incidents such as a question on political prisoners

being asked by an MP does not warrant the

attention it has been given. This is far too low a bar

to be saying there is change and improvement in

Burma. Even if by some miracle Parliament passed

a motion calling for the release of political prisoners,

the government is not obliged to act on it.

The Parliament has allowed some opening for a

small amount of political debate in Burma, which

is welcome, but such debate takes place in an

environment completely under the control of the

dictatorship, and in a constitutionally powerless

institution. This is not accidental, but rather part of

a carefully conceived plan to take over and control

political debate, which has traditionally been led

by the NLD, and so outside of the influence of

the dictatorship. The dictatorship wants political

debate to take place in a Parliament where it

has veto power, complete control, and which sits

behind giant walls in a remote capital, separated

from the population. It also serves the purpose of

giving an impression of change to the international

community.

Again, having an institution where issues are

discussed and debated by representatives elected

in a rigged election would not be new in Burma.

It took place under Ne Wins regime after he also

brought in a new constitution, and held a national

vote in 1974. Indeed, there were some surprisingly

robust debates, despite there only being one

political party, the Burma Socialist Programme Party.

However, those who went too far found themselves

jailed by Ne Win.

New Economic Advisor

Another drip in the flow of positive stories, warmly

welcomed by some, was the appointment of

U Myint, a friend of Aung San Suu Kyis, as a

government economic advisor. Attaching political

significance to this was rather clasping at straws. A

few weeks later wasnt even allowed to give a talk to

the NLD. One initiative credited to U Myint was an

economic workshop in Nay Pyi Daw, also hailed as

significant. However, some participants complained

it wasnt a workshop at all, merely a series of

presentations by government officials, without

opportunity for detailed questions or discussion.

More Visas For Visiting Diplomats

More and more visas started to be granted to

diplomats wanting to visit, and many of these same

diplomats attached political significance to this.

Aung Din, Executive Director of US Campaign for

Burma, brilliantly exposed the use of visa blackmail

by the regime in evidence to the US Congress

on 22nd June. Having made securing a visa so

difficult, diplomats now see merely getting a visa as

progress and significant. Its a cheap way of point

scoring for the dictatorship. In the 1990s visas were

much easier to obtain. The regime has learnt that

if they take a negative step, and later drop it, they

get praise or credit for doing so, even though the

situation hasnt genuinely progressed.

Aung San Suu Kyi Meets Aung Kyi

A meeting was held between Aung San Suu Kyi and

Aung Kyi, the minister appointed to liaise with her

after the uprising in 2007. This was widely reported

as the first meeting since the new government

came to power, rather than their 10th meeting over

a course of several years, which does not sound

quite as significant. Another meeting followed, the

eleventh.

In November 2002 Than Shwe boasted to the

Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi that

Aung San Suu Kyi had met with government

ministers on 13 occasions, and had met with a

liaison officer an incredible 107 times. These

meetings didnt lead to political reforms.

Allowing Aung San Suu Kyi to Leave

Rangoon

Here again the dictatorship used the technique

of taking a step back, then forward again, and

winning praise. State owned media first alluded

to violence that could take place if Aung San

Suu Kyi left the capital, effectively threatening a

repeat of the Depayin Massacre in which around

70 of her supporters were beaten to death. Then

the dictatorship ensured her first political trip

went peacefully, and got praised for it. Political

significance was attached to it. This tactic was

also used during Aung San Suu Kyis trial, where

incredibly, some praised them for leniency for not

imposing the maximum sentence of five years with

hard labour, and instead commuting the sentence to

a shorter period of house arrest. This is despite the

fact she should never have been on trial in the first

place.

It is not new for Aung San Suu Kyi to travel around

the country, she did so in the 1980s before being

placed under house arrest, and again in 2002 and

2003. On these occasions harassment gradually

increased over a series of trips, rather than being

intense and violent from the very first trip.

Aung San Suu Kyi addresses crowds in Mogok, Kachin

State in May 2003 during her tour of the country.

In November 2002 Than Shwe told the Japanese

Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi the government

was making efforts towards democratisation, and

that Aung San Suu Kyi was free to visit anywhere

inside of Myanmar, and the NLD was free to engage

in political activities. Seven months later his regime

attempted to assassinate her in the Depayin

Massacre, many NLD members were arrested, and

NLD offices were forced to close.

Propaganda Slogans Changed

Another much reported step has been the dropping

of some propaganda slogans in newspapers,

particularly ones attacking foreign media. But these

were only introduced into newspapers daily four

years ago at the time of the protests which began

in August 2007. This is another case of change that

isnt real change, just taking us back to the situation

in 2007.

While slogans attacking exile Burmese media

have been removed, censorship laws remain in

place. Twenty-three journalists are in jail. In the

same month as slogans attacking exile media were

removed, Democratic Voice of Burma journalist

Sithu Zeya, already serving an 8 year prison

sentence, was taken to court and charged with

further offences, and is facing another sentence of

up to 15 years. He has been repeatedly tortured.

Ceasefire Offer

There has also been an offer of ceasefire talks to

armed ethnic political parties. This must have been

received with incredulity by the Shan State Army North and Kachin Independence Organisation.

In March and June respectively they had been

attacked by the Burmese Army for refusing to

become Border Guard Forces under the control of

the Burmese Army, breaking decades-long ceasefire

agreements. The Burmese Army has been targeting

civilians in areas where it has broken ceasefire

agreements, with soldiers killing, raping, looting and

using forced labour.

Ceasefire offers which turn out to be highly

conditional, or in effect amount to demands to

surrender, have been made by dictatorships in

Burma literally dozens of times in the past 60 years.

There is nothing new in this proposal to think its

genuine this time. But the call served its purpose,

adding to the positive mood music and impression

of change.

Exiles Can Return?

A rumour has also emerged that Thein Sein told an

audience he was speaking to that political exiles

could return home and help the country develop.

Again some hailed this as a sign of change, even

though no amnesty was offered, no laws that led to

many of the exiles being jailed and forced to flee the

country have been repealed, and military attacks

of the kind that have forced hundreds of thousands

of people to flee their homes have increased, not

decreased.

Asked about this possible offer in an interview with

Radio Australia on 30th August, the UN Special

Rapporteur on Human Rights in Burma warned

exiles they could be arrested if they do return,

stating; The situation is that those who at this

moment may decide to express their opinions

against authorities may face the risk to be arrested

arbitrarily.

Even if an offer of amnesty was made, again, it

would not be new. Ne Win did the same, back in

1980. Again it wasnt a sign of any genuine change

on the way.

The other widely ignored factor is the importance of

ethnic representatives to be included in dialogue.

A process only involving the dictatorship and Aung

San Suu Kyi will not lead to a stable and lasting

solution to the problems in Burma. However, at the

present time the dictatorship is moving further away

from dialogue with ethnic groups, and is instead

opting for increased military attacks.

Aung San Suu Kyi in Newspapers

Here again, history is repeating itself.

The English-language New Light of Myanmar

printed a front-page picture of the dissident placing

flowers at the mausoleum during Wednesdays

official ceremonies honouring independence

leaders including her father Aung San who were

murdered 48 years ago. Chief among them was

her father Aung San....Her television appearance

suggests that the military government is willing to

accept her as a legitimately player in the public

political arena. She was last seen on state television

when she held talks with senior members of the

military government last year during her detention.

The Nation (Thailand) 21st July 1995

Aung San Suu Kyi Meets President Thein

Sein

The event perceived as most significant was the

meeting between Aung San Suu Kyi and Thein

Sein. Its another first that isnt quite a first. It is the

first meeting that Aung San Suu Kyi has held with

President Thein Sein, but not her first meeting with a

President. Than Shwe also held meetings with Aung

San Suu Kyi, as long ago as 1994. He knew then,

as does Thein Sein now, the propaganda value of

such meetings.

The problem there has been in the past with

meetings that Aung San Suu Kyi has had with

officials from the dictatorship at various levels is

that they have rarely moved on from basic talks and

into substantive dialogue about political change.

Of course, there must be a stage of confidence

building, and that may be the stage things are at

now, but experience tells us that the meeting in

itself does not necessarily indicate that the talks are

either anything more than public relations, or that

they will move on to issues of substance.

Aung San Suu Kyi appears in the state newspaper

New Light of Myanmar in November 2007.

Pictures of Aung San Suu Kyi on the pages of

newspapers and magazines in Burma have been

banned most of the time, so allowing pictures of

Aung San Suu Kyi to be pictured in media also

generated attention and speculation. Again though,

while not normal, allowing such pictures is certainly

not new. Such pictures have been published when

certain meetings have taken place, especially at

times when the dictatorship is keen to placate the

international community and people in Burma, such

as the meeting with UN Envoy Ibrahim Gambari in

November 2007, following the crushing of the Monkled pro-democracy uprising.

UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights

Visits Burma

The visit by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human

Rights in August 2011 wasnt his first, it was his

fourth, and there have been more than 40 visits

to Burma by UN Envoys and Special Rapporteurs

in the past 20 years. However, this was the first

visit since Thein Sein took control of the country,

and the Special Rapporteur had been refused

visas previously. In his statement following his trip

Thomas Quintana stressed that while there were;

real opportunities for positive and meaningful

developments to improve the human rights situation

and bring about a genuine transition to democracy,

at the same time; many serious human rights

issues remain...attacks against civilian populations,

extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, arbitrary

arrest and detention, internal displacement, land

confiscations, the recruitment of child soldiers, as

well as forced labour and portering.

In summary

Almost all of the above steps, often described as

progress and positive, have happened before

and did not lead to change in Burma. Given the

track record of the dictatorship, including Thein

Seins own record during his 14 years on the ruling

council of the dictatorship, it is wise to treat these

developments with a large degree of scepticism.

None of the steps taken so far take Burma any

closer to improving human rights and embarking on

a transition to democracy. Indeed, they have taken

place in a context of a worsening human rights

situation, with an increase in serious abuses which

violate international law being committed by the

Burmese Army in eastern and northern Burma.

What has happened so far appears to be public

relations, and not even new public relations,

Burma has seen all this before. There has been

no substance, no release of political prisoners, no

removal of repressive laws, and no end to attacks

on ethnic civilians. So far, the only thing that has

definitely changed with the dictatorship is that it has

improved its public relations work.

Why this flurry of initiatives now?

These events are not new, what is new is that they

have happened so closely together. Why? There are

several factors at play.

The new political structure in Burma is very

important to the dictatorship. They see themselves

as essential for holding the country together,

and knowing what is best for the population. It is

important to remember that Thein Sein is the man

who chaired the National Convention which drafted

the principles of the Constitution, and as such is one

of its main architects. The dictatorship saw the new

Constitution as creating a new political structure

through which they would legalise, legitimise and

consolidate their rule. It is designed to solve the

key problems they have faced, controlling domestic

politics, controlling ethnic populations, and gaining

international legitimacy and acceptance.

Fear of huge popular support for the NLD, and the

memory of the crushing defeat they received in

the 1990 elections, led the dictatorship to taking

an extremely hard line on the elections, creating

conditions which would make it impossible for the

NLD to take part. This destroyed what little credibility

the elections might have been able to garner for

them. They are now left with two choices, crack

down on the NLD as an illegal political party, or try

to coax the NLD to come in under the umbrella of

the Constitution, while making the minimum number

of concessions in the process.

In dealing with ethnic issues, their strategy has

also failed. Thein Sein took a very hard line on

making any concessions and granting rights,

protection and some level of autonomy to ethnic

people in the Constitution. All of the ethnic ceasefire

groups proposals were rejected. They were given

an ultimatum to register their political wings as

parties which would compete in a rigged election

for a powerless Parliament, and for their armed

wings to come under the control of the Burmese

Army. Many have rejected this. Thein Sein has

resorted to military solutions to impose his will,

but the increased conflict and associated human

rights abuses have also caused concern in the

international community.

With the Constitution, elections, and release of

Aung San Suu Kyi failing to persuade the USA, EU

and Canada to relax economic sanctions, and even

ASEAN baulking at the prospect of having Burma

as its Chair in 2014, delaying a decision, it was clear

that further steps would be needed. With a decision

on the ASEAN chairmanship likely to be made

before the end of the year, there is a clear sense of

urgency. To be turned down would be a major blow

to Thein Sein and the dictatorship.

This may help explain the flurry of activity, including

the meeting with Aung San Suu Kyi, and the attempt

to talk with the NLD to find a way to bring them

under the Constitution. It also explains the ceasefire

offer, talking peace while waging war.

What is highly unlikely, given their track record and

continuing actions, rather than words, is that this

has anything to do with genuine reform.

A next likely step will be the release of some political

prisoners, possibly even hundreds. Of course, the

release of any political prisoners is very welcome,

but it must be remembered that such a release

would not necessarily be about moving towards

political change, it will be about achieving the goals

of securing the ASEAN Chairmanship, and getting

sanctions relaxed.

When considering a response, the international

community should recall that again, the release

of political prisoners is not new. It would take the

release of almost a thousand political prisoners just

to return to the number prior to the 2007 uprising.

At that time having around 1,000 political prisoners

was considered unacceptable, and the international

community had been discussing how pressure

could be increased to help secure their release.

The dictatorship should not be rewarded for almost

doubling the number of political prisoners, and then

releasing just a few hundred.

The dictatorship has successfully engaged

in lies and delaying tactics for decades. They

take superficial actions designed to present the

impression that change could be round the corner,

but that corner is never turned. All the evidence so

far is that we are seeing more of the same. There is

potential to turn talk into action, but now is not the

time to adopt a wait and see approach, or for the

usual softly softly dialogue.

The international community is keen to encourage

change, and to reward change, but going too far in

welcoming steps taken so far which have not been

concrete, or even considering relaxing pressure

without significant steps being taken, will have

the opposite impact than intended. It will act as a

disincentive for real significant changes to be made.

Experience in dealing with the dictatorship is that

concessions have been wrung from them on the

rare occasions when a united firmer approach is

taken, for example the ILO Commission of Inquiry,

the Security Council considering a resolution on

Burma, and allowing more international aid workers

into the country after cyclone Nargis. Each resulted

in small, but concrete changes.

The softly softly wait and see approach has been

tried before when the dictatorship has indicated it

might be willing to change. That approach failed.

This time a different approach should be tried. A

concerted international effort needs to be made,

setting the dictatorship clear benchmarks and

timelines for change. The international community

has what the dictatorship wants. The international

community also has leverage. It is time to use it.

Published by Burma Campaign UK, 28 Charles Square, London N1 6HT

www.burmacampaign.org.uk info@burmacampaign.org.uk tel: 020 7324 4710

for Human Rights, Democracy

& Development in Burma

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st CenturyD'EverandEvidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st CenturyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Burmese Way To DemocracyDocument8 pagesThe Burmese Way To DemocracyBurma Independence Advocates (2009 - 2015)Pas encore d'évaluation

- BTI 2018 MyanmarDocument39 pagesBTI 2018 Myanmarcrasiba attirePas encore d'évaluation

- The Arrogance of Power: South Africa's Leadership MeltdownD'EverandThe Arrogance of Power: South Africa's Leadership MeltdownPas encore d'évaluation

- Democracy & Progress: DPP: Taking Action For Democracy, Launch-Ing A No-Confidence Motion For The PeopleDocument9 pagesDemocracy & Progress: DPP: Taking Action For Democracy, Launch-Ing A No-Confidence Motion For The PeopledppforeignPas encore d'évaluation

- Impeaching the Impeachment: Justice for President Park Geun-HyeD'EverandImpeaching the Impeachment: Justice for President Park Geun-HyePas encore d'évaluation

- Myanmar-US Relationship, Sanctions and Pro-Democracy ForcesDocument4 pagesMyanmar-US Relationship, Sanctions and Pro-Democracy ForcesLet's Work TogetherPas encore d'évaluation

- Nigeria's Journalistic Militantism: Putting the Facts in Perspective on How the Press Failed Nigeria Setting the Wrong Agenda and Excessively Attacking Ex-President Olusegun Obasanjo!D'EverandNigeria's Journalistic Militantism: Putting the Facts in Perspective on How the Press Failed Nigeria Setting the Wrong Agenda and Excessively Attacking Ex-President Olusegun Obasanjo!Pas encore d'évaluation

- Andrew Gavin Marshall Will Tunisia Transition From Tyranny Into Democratic Despotism 14 2 2011Document6 pagesAndrew Gavin Marshall Will Tunisia Transition From Tyranny Into Democratic Despotism 14 2 2011sankaratPas encore d'évaluation

- Update Briefing: Myanmar: Major Reform UnderwayDocument15 pagesUpdate Briefing: Myanmar: Major Reform UnderwayTint LwinPas encore d'évaluation

- A Test of Maturity, Not Unity Jan2013Document6 pagesA Test of Maturity, Not Unity Jan2013VincentWijeysinghaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ensayo Sobre Aung San Suu KyiDocument7 pagesEnsayo Sobre Aung San Suu Kyilolupyniwog2100% (1)

- 2013-Understanding Reforms in Myanmar Linking-En-redDocument20 pages2013-Understanding Reforms in Myanmar Linking-En-redakar PhyoePas encore d'évaluation

- Taylor BowerDocument1 pageTaylor BowerPyi Pai PhyoePas encore d'évaluation

- President's Speech Will Have Multiple Ramifications - J. C. WeliamunaDocument11 pagesPresident's Speech Will Have Multiple Ramifications - J. C. WeliamunaThavam RatnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Society For Burma - To NPT Thein Sein Speech 18.august-EnglDocument2 pagesCivil Society For Burma - To NPT Thein Sein Speech 18.august-EnglPugh JuttaPas encore d'évaluation

- Happy Lunar New Year!: DemocracyDocument16 pagesHappy Lunar New Year!: DemocracydppforeignPas encore d'évaluation

- To The Leaders Who Are The Hope of MyanmarDocument2 pagesTo The Leaders Who Are The Hope of MyanmarYe PhonePas encore d'évaluation

- Burmaissues: Fear, Faith, Friendship, ... Peace?Document8 pagesBurmaissues: Fear, Faith, Friendship, ... Peace?Kyaw NaingPas encore d'évaluation

- Friday, June 12, 2015 (MTE Daily Issue 63)Document53 pagesFriday, June 12, 2015 (MTE Daily Issue 63)The Myanmar TimesPas encore d'évaluation

- Myanmar Country Report: Status IndexDocument35 pagesMyanmar Country Report: Status Indexmarcmyomyint1663Pas encore d'évaluation

- Suu Kyi Offers To Step Down After Failure To Unite A Fractured BurmaDocument9 pagesSuu Kyi Offers To Step Down After Failure To Unite A Fractured BurmaThavam RatnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Explaining Myanmar's Regime Transition: The Periphery Is CentralDocument28 pagesExplaining Myanmar's Regime Transition: The Periphery Is CentralKristy LeungPas encore d'évaluation

- Taiwan Communiqué: Tsai Ing-Wen Becomes DPP ChairpersonDocument24 pagesTaiwan Communiqué: Tsai Ing-Wen Becomes DPP ChairpersonAlex LittlefieldPas encore d'évaluation

- China, Human Rights and MFNDocument23 pagesChina, Human Rights and MFNAlex LittlefieldPas encore d'évaluation

- An Accelerated Move - An Analysis of The 2012 Myanmar By-ElectionDocument12 pagesAn Accelerated Move - An Analysis of The 2012 Myanmar By-ElectionFnf Southeast East AsiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Taiwan Communiqué: President Chen: "Four Yes and One No"Document24 pagesTaiwan Communiqué: President Chen: "Four Yes and One No"Alex LittlefieldPas encore d'évaluation

- Organization Can Change A Whole Society," Aung San Su Kyi in A 14 May 1999 Interview Stating That The DireDocument8 pagesOrganization Can Change A Whole Society," Aung San Su Kyi in A 14 May 1999 Interview Stating That The DireKyaw NaingPas encore d'évaluation

- Naya Qanoon' and The 19th AmendmentDocument6 pagesNaya Qanoon' and The 19th AmendmentThavam RatnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Universal Values in Engaging With BeijingDocument5 pagesUniversal Values in Engaging With BeijingHoward39Pas encore d'évaluation

- Thein Sein A Man of War Not PeaceDocument2 pagesThein Sein A Man of War Not PeaceWahasal HariyPas encore d'évaluation

- Democracy in NigeriaDocument12 pagesDemocracy in NigeriaLawal Olasunkanmi ShittaPas encore d'évaluation

- The New Configuration of Power by Min Zin (JOD April 2016) PDFDocument17 pagesThe New Configuration of Power by Min Zin (JOD April 2016) PDF88demoPas encore d'évaluation

- 201231610Document48 pages201231610The Myanmar TimesPas encore d'évaluation

- Democracy & Progress: Really, Mr. Ma, It's About The Economy!Document7 pagesDemocracy & Progress: Really, Mr. Ma, It's About The Economy!dppforeignPas encore d'évaluation

- Myanmar's Stalled Transition: What's New? Aung San Suu Kyi's Government Is Halfway Through Its First TermDocument16 pagesMyanmar's Stalled Transition: What's New? Aung San Suu Kyi's Government Is Halfway Through Its First TermmayunadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Democratic Struggle of Myanman Under The Military RoleDocument17 pagesDemocratic Struggle of Myanman Under The Military RoleKeiren Faith Flores BaylonPas encore d'évaluation

- Jod 33 1Document185 pagesJod 33 1Daniel Bogiatzis GibbonsPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Current Southeast Asian AffairsDocument18 pagesJournal of Current Southeast Asian AffairsSanLynnAungPas encore d'évaluation

- Elections 2015 - Analysis and Commentary: Interview With Election Chief Tin Aye: 'As For Me, I've Accomplished My Duties'Document13 pagesElections 2015 - Analysis and Commentary: Interview With Election Chief Tin Aye: 'As For Me, I've Accomplished My Duties'Fuhad Bin MahmudPas encore d'évaluation

- Myanmar TimesDocument60 pagesMyanmar TimesMyat Zar GyiPas encore d'évaluation

- Waiting and DatingDocument14 pagesWaiting and DatingderejePas encore d'évaluation

- 1997 Zimbabwe's Turning PointDocument3 pages1997 Zimbabwe's Turning PointFaisal SulimanPas encore d'évaluation

- ISEAS Perspective 2016 65Document8 pagesISEAS Perspective 2016 65Zaw Moe AungPas encore d'évaluation

- Burma: Is It A Real Progress?Document2 pagesBurma: Is It A Real Progress?Burma Democratic Concern (BDC)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Arguemt EssayDocument4 pagesArguemt Essayapi-296516085Pas encore d'évaluation

- Proceedings Are Ongoing Against The Military of MyanmarDocument5 pagesProceedings Are Ongoing Against The Military of Myanmarparaschivescu marianPas encore d'évaluation

- 201334663Document60 pages201334663The Myanmar TimesPas encore d'évaluation

- Report 2017 Was A Period of Disillusionment Amidst Some Progress in Sri LankaDocument10 pagesReport 2017 Was A Period of Disillusionment Amidst Some Progress in Sri LankaThavamPas encore d'évaluation

- Entrevista ChunginmoonDocument5 pagesEntrevista ChunginmoonLilith WinchesterPas encore d'évaluation

- Burma Briefing 6Document8 pagesBurma Briefing 6Ian SurravillePas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary PresentationDocument10 pagesContemporary Presentationsuzette esplanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Democracy & Progress: DPP Chair Su Tseng-Chang's New Year MessageDocument9 pagesDemocracy & Progress: DPP Chair Su Tseng-Chang's New Year MessagedppforeignPas encore d'évaluation

- Burmaissues: The Shape of Things To Come?Document8 pagesBurmaissues: The Shape of Things To Come?Kyaw NaingPas encore d'évaluation

- Taiwan Communiqué: Former President Chen ArrestedDocument24 pagesTaiwan Communiqué: Former President Chen ArrestedAlex LittlefieldPas encore d'évaluation

- FridayDocument6 pagesFridayOlsPas encore d'évaluation

- DPP Newsletter Aug2012Document7 pagesDPP Newsletter Aug2012dppforeignPas encore d'évaluation

- 201438753Document72 pages201438753The Myanmar TimesPas encore d'évaluation

- Hs 311 AssignmentDocument10 pagesHs 311 Assignmentshah0023Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-Military Dictatorship in Myanmar 0306Document4 pagesAnti-Military Dictatorship in Myanmar 0306thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Singapore and Myanmar Relationship - SM Goh in Myanmar 10.06Document2 pagesSingapore and Myanmar Relationship - SM Goh in Myanmar 10.06thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- DR U Win Bilingual Burma NoFlyZone Part1 June2011Document45 pagesDR U Win Bilingual Burma NoFlyZone Part1 June2011Moe ZanPas encore d'évaluation

- EU Banned List 0809Document32 pagesEU Banned List 0809lovelamp88Pas encore d'évaluation

- Enemies of The Burmese Revolution 20101013Document76 pagesEnemies of The Burmese Revolution 20101013Pugh JuttaPas encore d'évaluation

- Aung San Suu KyiDocument53 pagesAung San Suu KyisssdddsssPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 July 1962 - Dictator General Ne Win Destroyed Students Union Building in Myanmar 02Document14 pages7 July 1962 - Dictator General Ne Win Destroyed Students Union Building in Myanmar 02thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Polaris Burmese Library - Singapore - Collection - Volume 144Document293 pagesPolaris Burmese Library - Singapore - Collection - Volume 144thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Senior General Than Shwe and Daw Kyaing Kyaing 001Document1 pageSenior General Than Shwe and Daw Kyaing Kyaing 001thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Polaris Burmese Library - Singapore - Collection - Volume 146Document251 pagesPolaris Burmese Library - Singapore - Collection - Volume 146thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Dictator Bo Ne Win and Bo Aung Gyi Destroyed Historic Students' Union BuildingDocument2 pagesDictator Bo Ne Win and Bo Aung Gyi Destroyed Historic Students' Union BuildingthakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Salai TMO-2010Document1 pageSalai TMO-2010kochinPas encore d'évaluation

- Polaris Burmese Library - Singapore - Collection - Volume 20Document205 pagesPolaris Burmese Library - Singapore - Collection - Volume 20thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Myanmar President U Thein Sein Speech 04.07.2012Document2 pagesMyanmar President U Thein Sein Speech 04.07.2012thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Military Dictorship in Myanmar - 1958-1960Document2 pagesHistory of Military Dictorship in Myanmar - 1958-1960thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Burmese Leaders' Belief in NumerologyDocument2 pagesBurmese Leaders' Belief in NumerologyRHinaa MoundCasforePas encore d'évaluation

- Australia Burma Sanctions List 221008Document12 pagesAustralia Burma Sanctions List 221008niknaymanPas encore d'évaluation

- 29jan10 AAPP (B) Annual Report 2009Document25 pages29jan10 AAPP (B) Annual Report 2009taisamyonePas encore d'évaluation

- Geo Spatial Visualization On Burma MyanmarDocument62 pagesGeo Spatial Visualization On Burma MyanmarAungs San OoPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Commanders in Myanmar ArmyDocument3 pagesList of Commanders in Myanmar ArmypostmanstarPas encore d'évaluation

- Polaris Burmese Library - Singapore - Collection - Volume 280Document349 pagesPolaris Burmese Library - Singapore - Collection - Volume 280thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Enemies of The Burmese Revolution 20101003Document75 pagesEnemies of The Burmese Revolution 20101003Ohnmar ShwePas encore d'évaluation

- 7 July 1962 - Dictator General Ne Win Destroyed Students Union Building in Myanmar 18Document4 pages7 July 1962 - Dictator General Ne Win Destroyed Students Union Building in Myanmar 18thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Policy BriefDocument16 pagesPolicy BriefLin AungPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hell Hound Is at LargeDocument2 pagesThe Hell Hound Is at LargeJacky PhyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal MyanmarDocument13 pagesJurnal Myanmarridho adjie13Pas encore d'évaluation

- U Ko Ko Hlaing, President U Thein Sein's Adviser, Empty Head and Empty HeartDocument1 pageU Ko Ko Hlaing, President U Thein Sein's Adviser, Empty Head and Empty HeartthakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- Real Story of Myanmar Activists in SingaporeDocument9 pagesReal Story of Myanmar Activists in SingaporethakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- 500KV Electric Power Tranmission Line in MyanmarDocument1 page500KV Electric Power Tranmission Line in MyanmarthakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 July 1962 - Dictator General Ne Win Destroyed Students Union Building in Myanmar 11Document2 pages7 July 1962 - Dictator General Ne Win Destroyed Students Union Building in Myanmar 11thakhinRITPas encore d'évaluation

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaD'EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (23)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziD'EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (157)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentD'EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (8)

- The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist RulersD'EverandThe Party: The Secret World of China's Communist RulersPas encore d'évaluation

- Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowD'EverandHeretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (57)

- The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyD'EverandThe Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (13)

- No Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesD'EverandNo Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (7)

- The Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr ZelenskyD'EverandThe Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr ZelenskyÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (4)

- Kilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsD'EverandKilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (2)

- Iran Rising: The Survival and Future of the Islamic RepublicD'EverandIran Rising: The Survival and Future of the Islamic RepublicÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (55)

- In Putin's Footsteps: Searching for the Soul of an Empire Across Russia's Eleven Time ZonesD'EverandIn Putin's Footsteps: Searching for the Soul of an Empire Across Russia's Eleven Time ZonesÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (20)

- The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017D'EverandThe Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (63)

- North Korea Confidential: Private Markets, Fashion Trends, Prison Camps, Dissenters and DefectorsD'EverandNorth Korea Confidential: Private Markets, Fashion Trends, Prison Camps, Dissenters and DefectorsÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (107)

- Unholy Alliance: The Agenda Iran, Russia, and Jihadists Share for Conquering the WorldD'EverandUnholy Alliance: The Agenda Iran, Russia, and Jihadists Share for Conquering the WorldÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (16)

- Palestine: A Socialist IntroductionD'EverandPalestine: A Socialist IntroductionSumaya AwadÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5)

- My Promised Land: the triumph and tragedy of IsraelD'EverandMy Promised Land: the triumph and tragedy of IsraelÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (149)

- The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017D'EverandThe Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (128)

- Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Writer's AwakeningD'EverandBirth of a Dream Weaver: A Writer's AwakeningÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Ask a North Korean: Defectors Talk About Their Lives Inside the World's Most Secretive NationD'EverandAsk a North Korean: Defectors Talk About Their Lives Inside the World's Most Secretive NationÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (31)

- Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower FutureD'EverandParty of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower FutureÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (10)

- Plans For Your Good: A Prime Minister's Testimony of God's FaithfulnessD'EverandPlans For Your Good: A Prime Minister's Testimony of God's FaithfulnessPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Iran: Everything You Need to Know, From Persia to the Islamic Republic, From Cyrus to KhameneiD'EverandUnderstanding Iran: Everything You Need to Know, From Persia to the Islamic Republic, From Cyrus to KhameneiÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (14)

- The World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Chinese Cultural RevolutionD'EverandThe World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Chinese Cultural RevolutionÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

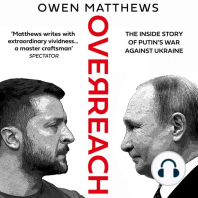

- Overreach: The Inside Story of Putin’s War Against UkraineD'EverandOverreach: The Inside Story of Putin’s War Against UkraineÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (29)