Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Academic Rigor and Student Engagement

Transféré par

Lisa LukerCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Academic Rigor and Student Engagement

Transféré par

Lisa LukerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Academic Rigor

If students are engaged in learning and taking greater responsibility for their own

learning, then increasing academic rigor is easy. The battle cry of most schools is to

increase test scores, even if scores are already relatively high; but you can't force

students to learn. Glasser (1998) purports that students choose to learn based on a sense

of belonging, freedom, power, and fun. Sousa (2005) found that for information to move

into long-term memory, it must have sense and meaning. Lecturing, drilling, and forcing

memorization will not increase learning. It may bring about a small, temporary bump in test

scores, but weeks later, the students will have little to show for their work, and little

foundation to build upon the following year.

I met with a group of teachers representing second grade through twelfth grade

to discuss rethinking instruction. During the discussion, an eleventhgrade teacher

commented, "Well not only do I have to concentrate on history, but I have to teach them

how to write. I don't know what your curriculum is in middle school, but our eleventh

graders can't write in paragraphs!" A middle school language arts teacher quickly

defended her curriculum with, "I spend a lot of time on paragraph construction because

they come to me, with no knowledge; but they leave my classroom with strong writing

skills. Our district needs to teach paragraph writing in the elementary grades." A secondgrade teacher who happened to have a stack of student stories with her pulled them out

and said, "I don't know what you're talking about. My second graders write great

paragraphs." We passed around the student writing samples and the upper-grade teachers

were incredulous . The first teacher to speak exclaimed, "If they write this well in

second grade, what happens to them when they get to high school?!"

Many students can memorize content for the moment. If you engage students'

minds in grappling with content through meaningful, authentic problems, they will build

knowledge and understanding for the long-term. If you increase their responsibility

for learning, offering them freedom and power, they will be able to accomplish more,

not remaining dependent on others to continue moving forward. You can then

increase academic rigor through well-crafted assignments, questions, differentiation,

collaboration, and more.

Engaged Learners

Busy students are not necessarily engaged students, nor are seemingly happy

students who are working in groups. Although "hands-on" activities are wonderful, what

you truly want are "minds-on activities. If you assume students are engaged in learning,

take a closer look to see if what they are doing is directly related to academically

rigorous content and if they are thinking deeply about that content. Suppose thirdgrade students are learning about the food chain. Consider the following scenarios as

we peek into three classrooms:

Students are locating information on the food chain from books and the

Internet and creating charts to demonstrate their understanding of the food

chain.

Students are designing a computer presentation on the food chain and are

working on adding sounds and transitions to make it more exciting.

Students are developing a presentation that considers what if" a member of

the food chain were to become extinct, under what conditions that might

happen, and how that would affect the rest of the food chain.

Although all three scenarios cover the content of the food chain, it is important to

consider how students spend the bulk of their time. In the first scenario, students are

most likely engaged in finding and reporting information. Doing so will lead them to

some level of understanding of the food chain, but the work is primarily "regurgitation" of

content. The second scenario assumes students have already found their information

and are reporting it using a digital presentation, which is a worthy goal. Their

engagement, however, is now in the digital presentation software. Again, although the

students are focusing on important skills, as the teacher, you must consider what content

is the goal of instruction. In this case, students are engaged in the use of software, not

understanding the food chain. The third scenario has students "grappling" with the

content itself-understanding the cause-and effect relationships that exist and using

higher-order thinking to consider future situations. All three of these scenarios might

occur when learning about

the food chain; the key is the amount of time allocated to each. Engaged learners need

to be grappling with curricular content in significant ways much of the time, no matter

what their ages.

Excerpts from Nancy Sullas Student Taking Charge Inside the LearnerActive-Technology-Infused Classroom

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Myth of Ability: Nurturing Mathematical Talent in Every ChildD'EverandThe Myth of Ability: Nurturing Mathematical Talent in Every ChildÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (3)

- Understanding The Mathematical LanguageDocument21 pagesUnderstanding The Mathematical LanguageLuisa DoctorPas encore d'évaluation

- Vanessa Ridout - Teaching Philosphy - 4Document2 pagesVanessa Ridout - Teaching Philosphy - 4api-645780752Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dynamics of Classroom LearningDocument3 pagesDynamics of Classroom LearningIrfan SayedPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Ams Essay - Trent CunninghamDocument6 pagesFinal Ams Essay - Trent Cunninghamapi-273541970Pas encore d'évaluation

- Artifact1 Scienceliteracy Te846Document36 pagesArtifact1 Scienceliteracy Te846api-249581708Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy of EducDocument8 pagesPhilosophy of Educapi-270000798Pas encore d'évaluation

- Progressive EducationDocument7 pagesProgressive EducationSharia Hanapia PasterPas encore d'évaluation

- Literacy PaperDocument7 pagesLiteracy Paperapi-533010724Pas encore d'évaluation

- ASSIGNMENTDocument6 pagesASSIGNMENTAnilGoyalPas encore d'évaluation

- B.Ed Assignment On School CurriculumDocument7 pagesB.Ed Assignment On School Curriculumkidzw246Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reading ResponsesDocument3 pagesReading Responsesapi-284912165Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1: The Function of Curriculum in SchoolsDocument5 pagesChapter 1: The Function of Curriculum in Schoolsapi-345689209Pas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Students Is Very Important To TeachingDocument6 pagesUnderstanding Students Is Very Important To TeachingMhango Manombo RexonPas encore d'évaluation

- Constructivist Discipline For A Student-Centered ClassroomDocument6 pagesConstructivist Discipline For A Student-Centered ClassroomRajesh MajumdarPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study-Reflection PaperDocument8 pagesCase Study-Reflection Paperapi-257359113Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ally Math PortfolioDocument2 pagesAlly Math Portfolioapi-307434464Pas encore d'évaluation

- Class Management PlanDocument8 pagesClass Management Planapi-505197281Pas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1:building The Context & Understanding Characteristics of Your StudentsDocument9 pagesModule 1:building The Context & Understanding Characteristics of Your Studentsapi-290358745Pas encore d'évaluation

- Distinct Learners in a Diverse Virtual ClassroomDocument33 pagesDistinct Learners in a Diverse Virtual ClassroomAngelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Signature PedagogyDocument9 pagesSignature Pedagogyapi-534924709Pas encore d'évaluation

- Resource Room - Tips For A Working Model: 1. Be PreparedDocument5 pagesResource Room - Tips For A Working Model: 1. Be PreparedLouneil Kenneth Tago GuivencanPas encore d'évaluation

- Writ 109ed wp1 DraftDocument5 pagesWrit 109ed wp1 Draftapi-439312924Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ed698 9 1Document4 pagesEd698 9 1api-664166199Pas encore d'évaluation

- Literacy Essay Test 1Document9 pagesLiteracy Essay Test 1api-303293059Pas encore d'évaluation

- American EducationDocument62 pagesAmerican EducationN San100% (1)

- Lesson Study Cycle 2 Literature SynthesisDocument4 pagesLesson Study Cycle 2 Literature Synthesisapi-615424356Pas encore d'évaluation

- Social Studies Defined: Interesting Quote Big IdeaDocument2 pagesSocial Studies Defined: Interesting Quote Big IdeasimplebreezePas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Observations DoneDocument6 pages5 Observations Doneapi-384852100Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bramley BP 7Document4 pagesBramley BP 7api-328474438Pas encore d'évaluation

- English EssayDocument5 pagesEnglish Essayapi-645986333Pas encore d'évaluation

- math framing statementDocument4 pagesmath framing statementapi-722424133Pas encore d'évaluation

- Top 10 CollaborativeDocument3 pagesTop 10 Collaborativeapi-317619349Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reflective Journal For Module 2Document4 pagesReflective Journal For Module 2api-350630106Pas encore d'évaluation

- Artifact 1Document6 pagesArtifact 1api-469670656Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anyon Critical Paper 1st DraftDocument4 pagesAnyon Critical Paper 1st Draftcbooth7Pas encore d'évaluation

- Social Studies Defined: Interesting Quote Big IdeaDocument2 pagesSocial Studies Defined: Interesting Quote Big IdeasimplebreezePas encore d'évaluation

- Description: Tags: Indeck-KenDocument2 pagesDescription: Tags: Indeck-Kenanon-592946Pas encore d'évaluation

- Contextual Learning - Assignment IIDocument4 pagesContextual Learning - Assignment IIArdelianda AugeslaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Guide To School Reform BOOKLET Build The Future Education (Humanistic Education) Compiled by Steve McCrea and Mario LlorenteDocument34 pagesA Guide To School Reform BOOKLET Build The Future Education (Humanistic Education) Compiled by Steve McCrea and Mario LlorenteJk McCreaPas encore d'évaluation

- In MiddleDocument3 pagesIn Middleapi-300394682Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Draft Signature Pedagodgy PaperDocument9 pagesFinal Draft Signature Pedagodgy Paperapi-253275550Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Synthesis of Middle School CurriculumDocument16 pagesSample Synthesis of Middle School CurriculumRon Knorr. PhDPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy of Education PaperDocument5 pagesPhilosophy of Education Paperapi-623772170Pas encore d'évaluation

- Do Something: Closing the Gap in Lesson PlansDocument5 pagesDo Something: Closing the Gap in Lesson PlansRoscela Mae D. ArizoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gradual Release of Responsibility 2Document5 pagesGradual Release of Responsibility 2Plug SongPas encore d'évaluation

- Action Research - 2Document10 pagesAction Research - 2api-509978569Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ed227 Inquiry Paper 12 4 18 CostelloDocument17 pagesEd227 Inquiry Paper 12 4 18 Costelloapi-384795626Pas encore d'évaluation

- IvyDocument4 pagesIvyKarl Ivan GervacioPas encore d'évaluation

- My Philosophy of Education PaperDocument9 pagesMy Philosophy of Education Paperapi-338530955Pas encore d'évaluation

- Differentiation ManagementDocument8 pagesDifferentiation ManagementLeio NeioPas encore d'évaluation

- Final ReflectionDocument11 pagesFinal Reflectionjfisher1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ued 496 Isabella Szczur Student Teaching Rationale and Reflection Paper 3Document7 pagesUed 496 Isabella Szczur Student Teaching Rationale and Reflection Paper 3api-445773759Pas encore d'évaluation

- Molzahn Racheal - Disciplinary Literacy PaperDocument7 pagesMolzahn Racheal - Disciplinary Literacy Paperapi-393590191Pas encore d'évaluation

- Disciplinary Literacy Position PaperDocument7 pagesDisciplinary Literacy Position Paperapi-487905844Pas encore d'évaluation

- inquiry part 2Document5 pagesinquiry part 2api-706158898Pas encore d'évaluation

- Literacy Case Study Te 846Document27 pagesLiteracy Case Study Te 846api-351865218Pas encore d'évaluation

- George J0817Document53 pagesGeorge J0817ZYRELYN MENDOZAPas encore d'évaluation

- Argument EssayDocument4 pagesArgument Essayapi-549251596Pas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated BibliographyDocument7 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-237191226Pas encore d'évaluation

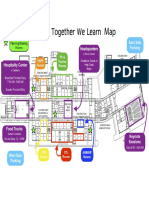

- WCHS Together We Learn MapDocument1 pageWCHS Together We Learn MapLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- Together We Learn Sessions at A Glance 2017Document4 pagesTogether We Learn Sessions at A Glance 2017Lisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- Volunteer BreakfastDocument1 pageVolunteer BreakfastLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- Volunteer PDFDocument1 pageVolunteer PDFLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- ICT Literacy CoachDocument4 pagesICT Literacy CoachLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Patriot Press: Administrative CornerDocument4 pagesThe Patriot Press: Administrative CornerLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- Volunteer BreakfastDocument1 pageVolunteer BreakfastLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- Volunteer PDFDocument1 pageVolunteer PDFLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- March NewsletterDocument4 pagesMarch NewsletterLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Patriot Press: Administrative CornerDocument5 pagesThe Patriot Press: Administrative CornerLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Patriot Press: Administrative CornerDocument4 pagesThe Patriot Press: Administrative CornerLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- Pine View TechTalk-2 PDFDocument1 pagePine View TechTalk-2 PDFLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- October NewsletterDocument4 pagesOctober NewsletterLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Patriot Press: Administrative CornerDocument4 pagesThe Patriot Press: Administrative CornerLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- InSync Information FlyerDocument3 pagesInSync Information FlyerLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- August Newsletter 2013Document2 pagesAugust Newsletter 2013Lisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- InSync Education FAQDocument2 pagesInSync Education FAQLisa LukerPas encore d'évaluation

- Ontario - Institutional Vision, Proposed Mandate Statement and Priority Objectives - Nipissing UniversityDocument17 pagesOntario - Institutional Vision, Proposed Mandate Statement and Priority Objectives - Nipissing UniversityclimbrandonPas encore d'évaluation

- Features of Choice Based Credit SystemDocument2 pagesFeatures of Choice Based Credit SystemFaizargarPas encore d'évaluation

- ARB 1911 C Outline Fall 2016Document3 pagesARB 1911 C Outline Fall 2016samyPas encore d'évaluation

- Tut Engineering CousesDocument228 pagesTut Engineering Cousesfarchipmm58Pas encore d'évaluation

- Online Grading SystemDocument3 pagesOnline Grading SystemMariella Angob0% (1)

- Teacher Education in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesTeacher Education in The PhilippinesRamil GofredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Practice of Learning in School/Reporting of GradeDocument2 pagesBest Practice of Learning in School/Reporting of GradeElma LlagasPas encore d'évaluation

- NZ Diploma Business Online 2010Document22 pagesNZ Diploma Business Online 2010debbiewalker87Pas encore d'évaluation

- DiaryDocument92 pagesDiaryAbhigyan RamanPas encore d'évaluation

- Elvira O. Pillo Practical Research - Maed - FilipinoDocument20 pagesElvira O. Pillo Practical Research - Maed - FilipinoAR IvlePas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing The Impacts of Student Transportation Via TransitDocument14 pagesAssessing The Impacts of Student Transportation Via TransitYana SerranoPas encore d'évaluation

- FFCS Academic Regulations - Version 210Document45 pagesFFCS Academic Regulations - Version 210asjdkfjskaldjf;klasdfPas encore d'évaluation

- Power of AttorneyDocument2 pagesPower of AttorneyCFBISD100% (1)

- Solving Math Equations ProblemsDocument26 pagesSolving Math Equations ProblemsJorrel SeguiPas encore d'évaluation

- Accommodations and Modifications GuideDocument64 pagesAccommodations and Modifications GuideCharline A. Radislao100% (1)

- SPARK Program Overview 2018Document3 pagesSPARK Program Overview 2018mortensenkPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalog 2011-2012 Skidmore CollegeDocument208 pagesCatalog 2011-2012 Skidmore CollegeMario Gustavo Juárez RosalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Msu-Tcto Preparatory High School Computerized Student Information System (Proposal)Document11 pagesMsu-Tcto Preparatory High School Computerized Student Information System (Proposal)Fermin J. Hamja100% (2)

- Brown University Brown UniversityDocument61 pagesBrown University Brown UniversityRuy CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- College ST - Scholastica: The ofDocument44 pagesCollege ST - Scholastica: The ofscholasticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gatton Academy 2009-10 School ProfileDocument20 pagesGatton Academy 2009-10 School ProfileGatton AcademyPas encore d'évaluation

- Preceptor Training - Post-Licensure Graduate Programs (MSN DNP)Document38 pagesPreceptor Training - Post-Licensure Graduate Programs (MSN DNP)Nipankar GuhaPas encore d'évaluation

- LU Course Catalog 10-11Document467 pagesLU Course Catalog 10-11gtsampras100% (1)

- Lesson Plan RPP Bahasa InggrisDocument5 pagesLesson Plan RPP Bahasa InggrisAli AmrullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To The Sargent Report On EducationDocument26 pagesIntroduction To The Sargent Report On EducationvamsibuPas encore d'évaluation

- Richard RetrosiDocument1 pageRichard Retrosimichelle92610Pas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: DSIB ESSAYDocument13 pagesRunning Head: DSIB ESSAYapi-435007358Pas encore d'évaluation

- Campus JournalismDocument5 pagesCampus JournalismxirrienannPas encore d'évaluation

- Sunway University College Monash University Foundation Year (MUFY) 2010Document24 pagesSunway University College Monash University Foundation Year (MUFY) 2010Sunway UniversityPas encore d'évaluation

- MIT Special Student Information SheetDocument7 pagesMIT Special Student Information SheetKrupa SaraiyaPas encore d'évaluation