Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

6.26 Priest Scandal Jump.a4

Transféré par

Reading_EagleCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

6.26 Priest Scandal Jump.a4

Transféré par

Reading_EagleDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A4

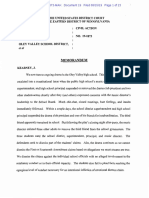

SUNDAY, JUNE 26, 2016

READING EAGLE, READING, PA.

Clergy sex abuse

Horric stories: Silence has ended, struggle goes on

[ From A1 >>> ]

Like many in their shoes, they havent had

the chance to see their alleged abusers convicted of a crime as the narrow window for

criminal charges as well as the window for

lawsuits had long closed by the time they

were able to come forward.

They are just a small few of those with ties

to the Berks and Tri-County areas. They are

among the slim percentage of victims who

have come forward, according to child trauma

researchers.

The lives of so many others, researchers say,

have been claimed by suicide, overdoses and

other diseases and conditions brought on by

a life of pain.

Here are their stories.

Mark Berkery

When Mark Berkery was a boy, he was raped

by a family friend, and afterward his parents

knew hed need good counseling to heal.

So they introduced

him to the man they

trusted most to help,

the Rev. Stanley Gana,

a priest at Ascension

of Our Lord Church in

Kensington.

The Berkerys were

Catholic and lived in

that north Philadelphia neighborhood,

and Gana convinced

them he could help Mark Berkery at 17.

the boy more than a

private counselor.

Ganas archdiocese

bio included youth

counseling among his

talents and interests.

He was very persuasive, said Berkery,

now 53, of Pottstown.

The rst counseling

session was in 1977,

when Berkery was 14.

When it wrapped up,

Gana forced a hug on Rev. Stanley Gana

him, even though he

knew it would make the boy uncomfortable,

Berkery said.

You have to realize that not everybody

wants to abuse you or have sex with you,

Berkery recalled Gana telling him.

More counseling meant more hugs, which

progressed to kisses on the cheek, then to

kisses on the mouth, Berkery said.

And over time, Gana began touching Berkerys genitals, then masturbating him, then

committing oral and anal sodomy on him,

said Berkery, whose account is backed up in a

2005 Philadelphia grand jury report on abuse

in the Philadelphia Archdiocese.

He knew what he was doing, Berkery said

of the way Gana groomed him as a victim.

It was very slow, very measured and very

insidious.

The abuse lasted for more than four years,

and over that time Gana raped Berkery hundreds of times, according to Berkery and the

grand jury report.

Gana also sexually abused countless boys

in a succession of parishes, the grand jury

report said.

Gana, now 73, was never charged because

by the time the grand jury report was released,

the two- or ve-year windows his victims had

to bring criminal charges (depending on when

they were abused) had long expired. Church

officials, however, have publicly called abuse

allegations against Gana credible.

A Reading Eagle reporter placed a phone

call to a number connected with the Orlando,

Fla., address that public records list for Gana.

A man answered the phone. He asked who was

calling when asked by the reporter if he was

Gana. When the reporter identied himself,

the man quickly hung up.

Further calls to the same number made over

two weeks were not answered. Messages were

left indicating a reporter was seeking Ganas

comments about accusations that he molested

a child. Those messages were not returned. Last

week, the number had been disconnected.

The grand jury report states the archdiocese

had been hearing allegations about Ganas

sexual misconduct since the early 1970s. Berkery is appalled that the archdiocese allowed

Gana continued access to boys years after

being told of his abuse.

If the diocese had done its job correctly, Id

have never been abused, he said. All theyve

done is hide behind secret settlements and

nondisclosure agreements, and all thats done

is perpetuated the problem.

He was known to kiss, fondle, anally sodomize,

and impose oral sex on his victims. He took

advantage of altar boys, their trusting families,

and vulnerable teenagers with emotional

problems. He brought groups of adolescent

male parishioners on overnights and would

rotate them through his bed. He collected

nude pornographic photos of his victims. He

molested boys on a farm, in vacation houses,

in the church rectory. Some minors he abused

for years.

When Gana took Berkery on trips he often

took other boys as well and abused them, too,

the grand jury report said.

Gana would have them take turns coming

into his bed, the report said, and Gana sometimes sexually assaulted Berkery and another

boy at the same time.

He abused me at least once a week for those

four years, and usually more than once a week,

Berkery said.

Those assaults occurred most often in the

Ascension of God rectory where Gana lived,

Berkery said.

When they were alone in church, Gana fondled him almost constantly, Berkery said.

One year I missed the Christmas Mass, so

he brought me into a sacristy for a private

Mass, Berkery said. He locked the door and

raped me.

The first year that Gana was counseling

Berkery, he had the boys family spend the

summer on the more than 100-acre property he owned in Friendsville, Susquehanna

County, Berkery said.

There Gana raped him out of view of his

parents, Berkery said. He also brought him

back the next three summers without Berkerys family to assault him again and again,

Berkery said.

Gana also abused Berkery on trips to Disney

World, Niagara Falls, Notre Dame University

and the Jersey Shore, turning what should

have been special memories for an inner city

kid into a nightmare that still haunts him,

Berkery said.

Gana was good at isolating Berkery to

make him easier to prey on, telling him that

he should be seen but not heard, and that he

wasnt allowed to speak with anyone about

their time together, Berkery said.

Gana even turned the boy against his own

family, while also giving Berkerys parents

money when they needed it for things like

groceries to keep them on his side, Berkery

said.

He was not only working me, he was working them, Berkery said.

Emotional, mental toll

Berkery separated from Gana when he went

to college, but his problems didnt go away.

I didnt have the same college experience as

other people, he said. I was suicidal.

Berkery went to the student health center

on campus, which was the rst place he ever

talked about the abuse hed suffered.

After college, Berkery struggled with substance abuse.

When he got sober in 1995, he called the

archdiocese to report Ganas abuse.

The diocese arranged for him to meet Monsignor William Lynn, who at the time was

often the rst one alleged abuse victims within

the diocese talked to. Lynn was convicted in

2012 of putting a known child molester, the

Rev. Edward J. Avery, in contact with children;

Avery was convicted and remains jailed on

child abuse charges. Lynn remains in prison

while his case is on appeal.

After Berkery entered the room, he said

these were the rst words he heard from Lynn:

We dont make nancial settlements.

Berkery has since learned that wasnt true.

But more disturbing to him was that hed

never asked for money, yet that was still the

churchs focus.

What I wanted was to make sure he (Gana)

didnt have access to any more kids, Berkery

said.

Gana was ultimately defrocked in 2006

as a result of credible allegations of sexual

abuse of a minor, according to a listing of the

status of accused priests on the archdioceses

website.

The grand jury in 2005 used Ganas case to

illustrate church leaders response to abuse.

According to the report, Lynn justied not

removing Gana after learning he had abused

children by saying that Gana was not a pure

pedophile because he also had sex with adult

women, abused alcohol and stole money from

the church.

According to the grand jury report, Gana

was moved to a lower-prole role in 1997 but

continued to serve as a priest until 2002, when

he was removed from his assignment during national attention on abuse by Boston

priests.

Countless boys

Berkery told Lynn that he knew there were

The grand jury report detailed Ganas acmany other victims of Gana, but Lynn told him

tions this way:

He sexually abused countless boys in a suc- that he shouldnt try to nd other victims or

cession of Philadelphia Archdiocese parishes. speak to those alleging abuse, Berkery said.

The diocese referred Berkery to a nun for

counseling, but that therapy was mostly her

telling him any sexual contact he had with

Gana was his fault because he let it happen,

Berkery said.

Berkery said child abuse victims already

live with enough guilt and shame, but to have

a nun make him feel even worse about what

happened was unconscionable.

Kenneth A. Gavin, archdiocese spokesman,

said he couldnt comment on specic victims

cases.

But he said the archdioceses response to

reports of abuse has changed dramatically

since the 1990s. Now, he said, law enforcement is immediately notied and outreach to

victims and the investigation of the allegations

are handled separately and by former law

enforcement professionals, not clergy.

Berkery has been identied in other news

accounts as the boy described in the grand

jury report. He also testied about his alleged

abuse by Gana during Lynns trial. And he has

been involved in activism for abuse victims at

the state Capitol.

I cant trust people

Berkery remained a devout Catholic and

continued to attend Masses. But more than

once while standing in the back of the church,

he heard older women gossiping about boys

victimized by priests, not knowing he was

one of them.

Theyd say we were lying, and we just

wanted the money, that we encouraged it

(the abuse) and that we were the ones who

molested the priests, he said.

But what Berkery said ultimately crushed

his Catholicism and his faith in God was a

meeting with Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua,

whom until that moment Berkery had believed would help him get justice.

The grand jury report says Bevilacqua refused to grant Berkerys request for a meeting

in 1995. But Berkery said he eventually met

with the cardinal years later.

But basically he just told me to shut up,

Berkery said. That was it for me.

The grand jury, citing the archdioceses

own les, said Bevilacqua knew about sexual

abuse of children by archdiocean priests and

was engaged in efforts to conceal it. The 2011

grand jury that recommended charges against

Lynn said it did not recommend charging

Bevilacqua only because there wasnt enough

evidence directly linking him to the two specic cases that led to charges against Lynn.

Bevilacqua died in 2012.

Several times a day Berkery still thinks of

his abuse, the pain rushing back, along with

the feeling of being helpless.

Im 53 and Im still guring it out, still dealing with the effects of that abuse, he said.

Berkery cant work now, relying on disability payments he receives for post-traumatic

stress disorder and major depressive disorder,

he said.

He rarely leaves the house other than to pick

up groceries or for the therapy appointments

he attends four times a week, he said.

I cant be around people, he said. I cant

trust people.

He supports the bill that would extend time

limits for fellow abuse victims to bring criminal charges or le lawsuits. But he wishes a

proposal to revive already-expired lawsuits

went further.

It eliminates people who are over 50 and

were victimized, he said. I want those people

to have their day in court and their justice,

too.

Ive been seeking justice for more than 20

years, but Im always getting cut off by some

ambiguous (age) number. First the age was

raised to 30, and now theyre trying for 50,

but each time Im just outside of it.

Doesnt want money

Berkery said he still has no interest in money from the church, but very much wants

Gana to receive his just punishment in a

courtroom.

Society says thats where these things

should be settled (nowadays), he said. Ive

been seeking true justice for years, but Ive

come up against roadblock after roadblock

after roadblock.

Berkery not only received no monetary

compensation from the church, but no direct

apology or admission of guilt, he said.

The archdiocese pays for his counseling,

sending the payments directly to his therapist,

and for his medication. He used to receive letters from the archdiocese telling him they were

paying his counseling bills out of charitable

or compassionate concern, but the letters

now just indicate his bills are being paid.

Gavin said the archdiocese, as its support

services for victims evolved, stopped using

the language about charitable concern in correspondence to victims.

Berkery said the letters dont acknowledge

the impact of the abuse.

They dont mention its because they ruined

my life, he said.

Thomas Humma

The day is seared into Thomas Hummas

memory.

It was the moment,

he said, that he nally

broke free of the priest

who snaked into a

central role in his life

only to sexually molest

him.

Though Humma

hasnt told his story

publicly until now,

parts of it have been

recounted in media Thomas Humma at 12.

reports, at press conferences, even during

state legislative sessions.

His story is intertwined with that of his

childhood friend Mark

Rozzi, whos since become a state lawmaker

representing part of

Berks County and an

advocate for abuse

victims.

Their alleged abuser, Edward R. Graff

Edward R. Graff, died

in 2002 while awaiting trial in Texas on charges he abused a 15-year-old boy there.

Humma, who grew up in Reading and now

lives on the West Coast, gures Graff pushed

his luck the day he took both boys together

into the rectory at Holy Guardian Angels in

Muhlenberg Township. At the time, Humma

was 12, and Rozzi was 13.

To Humma, Graff s transition from surrogate uncle to sexual predator had been seamless and subtle. It wasnt until that day that

he was suddenly hit with the reality of what

was happening.

He remembers lying naked and half-drunk

on Graff s bed with pornography playing on

the television as Rozzi darted out of the shower, picked up his clothes and motioned that it

was time to leave.

Im in the room and Rozzi comes running,

Humma said. And I saw pure fear in his eyes.

And a switch went on.

Humma said he would later learn Graff had

raped Rozzi in the shower, the act that pushed

the abuse over the edge and cost Graff both

boys trust. But then in the room, Humma saw

Rozzi, the alpha male in his group of friends,

broken and frightened like a little boy.

He didnt say anything to me, Humma said.

He just looked at me. It was the scariest thing

that I have ever dealt with.

Rozzi conrmed the events of that day.

The boys made a pact never to speak about

what had happened. The secret drove a wedge

between them, Humma said, and the onceclose friends became distant acquaintances.

It wasnt until both were in their late 30s

and ready to talk about their abuse that they

began to repair their friendship.

Humma promised his parents when he

eventually told them about the abuse that

he wouldnt go public with his story until

after his grandmothers death. She was a devout Catholic and he said he has no doubt the

heartbreak would have killed her.

Master manipulator

Humma was a seventh-grader at Holy

Guardian Angels school when Graff arrived

at the school and parish.

Graff would pay Humma and other boys to

rake leaves and do other chores around the

campus. Graff and Humma would talk about

football and horses. Soon, Graff was a regular

guest at Hummas family cookouts. The family

trusted him.

He was a master, there was no doubt, Humma said. He was a master manipulator.

It wasnt long, Humma said, before he and

Graff were taking trips together.

They would go to Penn National Race Course

near Harrisburg where Graff would bet on the

horses and give Humma money to do the same.

Graff gave Humma a snap-brim newsboy cap to

wear, saying it made the boy look older. Humma

said the sight of such a cap still triggers painful

ashbacks. So does the smell of cigar smoke,

which permeated Graff s car and rectory.

Humma said Graff started to sneak him into

the rectory, telling him that he wasnt supposed to be there and it must be kept secret.

They would drink wine and talk about sports.

Humma said he was honored and attered

that Graff treated him like an adult. He felt

special.

The transition happened slowly.

First, he said, Graff would show him pornography and talk with him about sex, telling

him he needed a teacher. That led to Graff

[ >>> 5 ]

masturbating him while touching

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Marys of the Bible: The Original #MeToo MovementD'EverandThe Marys of the Bible: The Original #MeToo MovementÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Epistles on Clergy Abuse: The Clergy Abuse Scandal Chronicled Through LettersD'EverandEpistles on Clergy Abuse: The Clergy Abuse Scandal Chronicled Through LettersPas encore d'évaluation

- PDFDocument8 pagesPDFAnonymous k8GaVHKPas encore d'évaluation

- Clergy Abuse 2 Final ReportDocument128 pagesClergy Abuse 2 Final Reportcsand1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ernie Willis Accused of Raping Teenage Girl Who Belonged To His ChurchDocument6 pagesErnie Willis Accused of Raping Teenage Girl Who Belonged To His ChurchfourbzboysmomPas encore d'évaluation

- Eileen Flynn June 9 2008Document4 pagesEileen Flynn June 9 2008Eboni HarrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Alahverdian Family Emails With ParkerDocument12 pagesAlahverdian Family Emails With ParkerNBC 10 WJARPas encore d'évaluation

- Was Cardinal Bernadin A Secret Satanist? (Bro. Michael Dimond)Document7 pagesWas Cardinal Bernadin A Secret Satanist? (Bro. Michael Dimond)luvpuppy_ukPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Jacques Story Aug 08Document4 pagesMichael Jacques Story Aug 08Tracy GilmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Reed 40: Submitted By: Submitted ToDocument15 pagesReed 40: Submitted By: Submitted ToStephanie EumaguePas encore d'évaluation

- Rev. Walker Article, 1-3-2013Document3 pagesRev. Walker Article, 1-3-2013Gilion DumasPas encore d'évaluation

- 6.26 Priest Scandal Jump.a5Document1 page6.26 Priest Scandal Jump.a5Reading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Spotlight Church Abuse Report - Church Allowed Abuse by Priest For Years - The Boston GlobeDocument19 pagesSpotlight Church Abuse Report - Church Allowed Abuse by Priest For Years - The Boston GlobeBenevant MathewPas encore d'évaluation

- Matt Lauer Open LetterDocument3 pagesMatt Lauer Open LetterNew York Post100% (4)

- Child Sexual Abuse Investigation in AustraliaDocument4 pagesChild Sexual Abuse Investigation in AustraliasirjsslutPas encore d'évaluation

- False Intimacy: Understanding the Struggle of Sexual AddictionD'EverandFalse Intimacy: Understanding the Struggle of Sexual AddictionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (9)

- Boy Erased: A Memoir of Identity, Faith, and Family by Garrard Conley | Conversation StartersD'EverandBoy Erased: A Memoir of Identity, Faith, and Family by Garrard Conley | Conversation StartersPas encore d'évaluation

- Hell Minus One From The Child Abuse Wiki - Confirmed Satanic Ritual AbuseDocument2 pagesHell Minus One From The Child Abuse Wiki - Confirmed Satanic Ritual Abusesmartnews100% (2)

- The Lisa Miller StoryDocument7 pagesThe Lisa Miller StoryLoneStar1776Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Disappearance of Bianca Carrasco : An Anthology of True CrimeD'EverandThe Disappearance of Bianca Carrasco : An Anthology of True CrimePas encore d'évaluation

- Pedophilia - Jimmy Hinton & Church ProtectDocument164 pagesPedophilia - Jimmy Hinton & Church ProtectRuben Miclea50% (2)

- Woman Says Mike Bickle Used Prophecy To Sexually Abuse HerDocument1 pageWoman Says Mike Bickle Used Prophecy To Sexually Abuse HerVanessa MainãPas encore d'évaluation

- Do RCs Know RSCH Shows People Trust Rabid DOGs More Than Priests?Document6 pagesDo RCs Know RSCH Shows People Trust Rabid DOGs More Than Priests?.Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Last Thing He Told Me: A Novel by Laura Dave: Conversation StartersD'EverandThe Last Thing He Told Me: A Novel by Laura Dave: Conversation StartersPas encore d'évaluation

- Faraway: A Suburban Boy's Story as a Victim of Sex TraffickingD'EverandFaraway: A Suburban Boy's Story as a Victim of Sex TraffickingÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Valentina Blackhorse Dreamed of Being A Navajo Leader Then Died of Covid-19Document4 pagesValentina Blackhorse Dreamed of Being A Navajo Leader Then Died of Covid-19api-633254734Pas encore d'évaluation

- Strength in Vulnerability: Reclaimed Voices of Domestic Violence & Sexual AssaultD'EverandStrength in Vulnerability: Reclaimed Voices of Domestic Violence & Sexual AssaultPas encore d'évaluation

- Karen Hinkley's Response To TVC's EmailDocument20 pagesKaren Hinkley's Response To TVC's EmailwatchkeepPas encore d'évaluation

- Praise The Lord & Pass The Pastrami: A Jewish Psychiatrist's Family Finds Their MessiahD'EverandPraise The Lord & Pass The Pastrami: A Jewish Psychiatrist's Family Finds Their MessiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Finishing Strong-CreedDocument12 pagesFinishing Strong-CreedLee MasukaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gone GirlDocument27 pagesGone GirlUdit SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Prisoners of FearDocument267 pagesPrisoners of FearCindy GoddardPas encore d'évaluation

- Hymns of a Raving Heart: The True Crime of S. Althea BerrieD'EverandHymns of a Raving Heart: The True Crime of S. Althea BerriePas encore d'évaluation

- From Anger to Intimacy: How Forgiveness Can Transform Your MarriageD'EverandFrom Anger to Intimacy: How Forgiveness Can Transform Your MarriageÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Rape CasesDocument2 pagesRape CasesChristine Joy AbrantesPas encore d'évaluation

- Finding the Will of God in a Crazy, Mixed-Up WorldD'EverandFinding the Will of God in a Crazy, Mixed-Up WorldÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

- Innocence Beyond The Glass House: A Story of Injustice and the Final Battle for FreedomD'EverandInnocence Beyond The Glass House: A Story of Injustice and the Final Battle for FreedomPas encore d'évaluation

- Sexual Abuse in The ChurchDocument28 pagesSexual Abuse in The ChurchMoriah MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Hell Minus One - Signed Verified Confessions of Satanic Ritual AbuseDocument3 pagesHell Minus One - Signed Verified Confessions of Satanic Ritual Abusesmartnews100% (2)

- Summary of Boy Erased: A Memoir of Identity, Faith, and Family: Conversation StartersD'EverandSummary of Boy Erased: A Memoir of Identity, Faith, and Family: Conversation StartersPas encore d'évaluation

- Is This Domestic Abuse?: A Handbook for Christian Women Who Feel Hopeless in Their MarriageD'EverandIs This Domestic Abuse?: A Handbook for Christian Women Who Feel Hopeless in Their MarriagePas encore d'évaluation

- Home Should Be Safe: Hope and Help for Domestic Violence VictimsD'EverandHome Should Be Safe: Hope and Help for Domestic Violence VictimsPas encore d'évaluation

- Philadelphia Report: The Sixth Report On The Catholic Abuse Crisis (Philadelphia, EEUU - 2005)Document423 pagesPhiladelphia Report: The Sixth Report On The Catholic Abuse Crisis (Philadelphia, EEUU - 2005)Vatican Crimes ExposedPas encore d'évaluation

- Church Allowed Abuse by Priest For Years - The Boston GlobeDocument14 pagesChurch Allowed Abuse by Priest For Years - The Boston GlobePriscila ReigadaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Price of Safety: Hidden Costs and Unintended Consequences for Women in the Domestic Violence Service SystemD'EverandThe Price of Safety: Hidden Costs and Unintended Consequences for Women in the Domestic Violence Service SystemPas encore d'évaluation

- Script KatieDocument12 pagesScript KatieMāh Wīßh FātīmāPas encore d'évaluation

- Domestic Abuse Victim RememberedDocument5 pagesDomestic Abuse Victim RememberedTony GicasPas encore d'évaluation

- People of The Philippines vs. Pedro Buado, JR., y CiprianoDocument19 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Pedro Buado, JR., y CiprianoMichael VariacionPas encore d'évaluation

- Aileen WuornosDocument3 pagesAileen WuornosJesseBajenaru100% (1)

- Jon Jacobo Can't Have Any More VictimsDocument7 pagesJon Jacobo Can't Have Any More VictimsMissionLocal100% (2)

- Instances of Child Sexual Abuse Allegedly Perpetrated by Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints-2017-06Document316 pagesInstances of Child Sexual Abuse Allegedly Perpetrated by Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints-2017-06Manu Zein100% (1)

- DBT in BPD Case PresentationDocument105 pagesDBT in BPD Case PresentationPrasanta Roy100% (1)

- The Living Sacrifice on an Assignment: God Turns Curses into BlessingD'EverandThe Living Sacrifice on an Assignment: God Turns Curses into BlessingPas encore d'évaluation

- Letter To Legislative LeadersDocument2 pagesLetter To Legislative LeadersReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- BoyertownLetter Busing 20210921Document1 pageBoyertownLetter Busing 20210921Reading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- 13 Reading Gang Members IndictedDocument53 pages13 Reading Gang Members IndictedReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Board Decision On BieberDocument4 pagesBoard Decision On BieberReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Accidental Shootings by Police (The Associated Press)Document125 pagesAccidental Shootings by Police (The Associated Press)Reading_Eagle100% (1)

- Lebanon County Plane Crash ReportDocument5 pagesLebanon County Plane Crash ReportReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- F&M Poll Release October 2019Document34 pagesF&M Poll Release October 2019Reading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Losing The News The Decimation of Local Journalism and The Search For SolutionsDocument114 pagesLosing The News The Decimation of Local Journalism and The Search For SolutionsReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Legislative Proposals For Property Tax ReformDocument5 pages5 Legislative Proposals For Property Tax ReformReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Bail LawsuitDocument19 pagesBail LawsuitReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Nolde Forest Trail MapDocument1 pageNolde Forest Trail MapReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Canine Parvovirus ExplainedDocument2 pagesCanine Parvovirus ExplainedReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Full Report Hpsci Impeachment Inquiry - 20191203Document300 pagesFull Report Hpsci Impeachment Inquiry - 20191203Mollie Reilly100% (36)

- Bail LawsuitDocument19 pagesBail LawsuitReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- President Trump Ukraine President CallTranscript09.2019Document5 pagesPresident Trump Ukraine President CallTranscript09.2019Reading_Eagle0% (1)

- Oley Drama CaseDocument23 pagesOley Drama CaseReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- U.S. Sen. Bob Casey and U.S. Rep. Chrissy Houlahan's Letter To ICEDocument5 pagesU.S. Sen. Bob Casey and U.S. Rep. Chrissy Houlahan's Letter To ICEReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- U.S. Department of Transportation's August 2019 Guidance On Nondiscrimination On The Basis of Disability in Air TravelDocument28 pagesU.S. Department of Transportation's August 2019 Guidance On Nondiscrimination On The Basis of Disability in Air TravelReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Whistleblower Complaint Against President TrumpDocument9 pagesWhistleblower Complaint Against President TrumpYahoo News90% (84)

- Dog Attack SurveyDocument9 pagesDog Attack SurveyReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Pennsylvania Game Commission Draft CWD Response Plan Public Comment FormDocument2 pagesPennsylvania Game Commission Draft CWD Response Plan Public Comment FormReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Pennsylvania Game Commission Draft CWD Response PlanSept122019Document37 pagesPennsylvania Game Commission Draft CWD Response PlanSept122019Reading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- W. Glenn Steckman LawsuitDocument9 pagesW. Glenn Steckman LawsuitReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Pennsylvania State Pension StudyDocument393 pagesPennsylvania State Pension StudyReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Service Animal Definitions Compared by The U.S. Department of TransportationDocument13 pagesService Animal Definitions Compared by The U.S. Department of TransportationReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- F&M Poll Release August 2019Document35 pagesF&M Poll Release August 2019jmicekPas encore d'évaluation

- Right-Sizing Tuition at Albright CollegeDocument2 pagesRight-Sizing Tuition at Albright CollegeReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Kevin Barnhardt - Berks Co. Residential Center AnnouncementDocument2 pagesKevin Barnhardt - Berks Co. Residential Center AnnouncementReading_EaglePas encore d'évaluation

- F&M Poll Release August 2019Document35 pagesF&M Poll Release August 2019jmicekPas encore d'évaluation

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Somalata (Research Paper)Document5 pagesSomalata (Research Paper)ringboltPas encore d'évaluation

- Short Story 8Document57 pagesShort Story 8tgun25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dhammika Broken-Buddha PDFDocument66 pagesDhammika Broken-Buddha PDFSajalmeghPas encore d'évaluation

- Entire Bible in 180 DaysDocument2 pagesEntire Bible in 180 DaysJaden_JPas encore d'évaluation

- Conflict ResolutionDocument15 pagesConflict ResolutionAngelik77Pas encore d'évaluation

- Is Female To Male As Nature Is To CultureDocument28 pagesIs Female To Male As Nature Is To CulturePăun Mihnea-DragoșPas encore d'évaluation

- Buddhist Tenet System by Rigpa WikiDocument3 pagesBuddhist Tenet System by Rigpa WikiAadarsh LamaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Essays PteDocument6 pagesSample Essays PteFatima JabeenPas encore d'évaluation

- The KEY To The Crucifixion DateDocument11 pagesThe KEY To The Crucifixion DateAninong BakalPas encore d'évaluation

- Debts Under Hindu Law1 PDFDocument12 pagesDebts Under Hindu Law1 PDFVivek Rai100% (3)

- Mark Juergensmeyer Is Religion The ProblemDocument11 pagesMark Juergensmeyer Is Religion The ProblemMaya GeorgPas encore d'évaluation

- V Scott Oconnor Mdy and Other Citis of The Past in BurmaDocument494 pagesV Scott Oconnor Mdy and Other Citis of The Past in BurmaSawPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 - Riba Its Prohibition and ClassificationDocument21 pages2 - Riba Its Prohibition and Classificationhekmat mayarPas encore d'évaluation

- ForbiddenDocument436 pagesForbiddenMuhammad Tariq NiazPas encore d'évaluation

- The ExpositorDocument501 pagesThe ExpositorAmadi Pierre0% (1)

- Poets of The Tang Dynasty: Li PoDocument52 pagesPoets of The Tang Dynasty: Li PothinorangelinePas encore d'évaluation

- How-To-Study-The-Bible-Kenneth-Copeland-Christiandiet.comDocument7 pagesHow-To-Study-The-Bible-Kenneth-Copeland-Christiandiet.comDaniel Abraham100% (1)

- God Almighty, We Adore Thee PDFDocument1 pageGod Almighty, We Adore Thee PDFSolomonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Son of The East and The Sun of The West Swami KrishnanandaDocument98 pagesThe Son of The East and The Sun of The West Swami KrishnanandakartikscribdPas encore d'évaluation

- Little JohnnyDocument7 pagesLittle JohnnysumitcooltoadPas encore d'évaluation

- Gerald Massey - The Devil of Darkness in The Light of EvolutionDocument18 pagesGerald Massey - The Devil of Darkness in The Light of Evolution2thirdsworld100% (1)

- GilesCoreyoftheSalemFarms 10133323 PDFDocument95 pagesGilesCoreyoftheSalemFarms 10133323 PDFGremlin ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Sri ChakraDocument3 pagesSri ChakraAnonymous gmzbMup100% (1)

- Ajay Kumar Gupta: Curriculum-VitaeDocument2 pagesAjay Kumar Gupta: Curriculum-VitaePeter SamuelPas encore d'évaluation

- It's The Most Wonderful Time of The YearDocument2 pagesIt's The Most Wonderful Time of The YearHarryPas encore d'évaluation

- Reference Material For Study Training Course With Mr. Morinaka - 15 & 16 Oct 2016Document68 pagesReference Material For Study Training Course With Mr. Morinaka - 15 & 16 Oct 2016Sinjini Chanda100% (1)

- Buddhist Councils Everything You Need To KnowDocument4 pagesBuddhist Councils Everything You Need To KnowNITHIN SINDHEPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning About The Angels: Jibreel Meekaa'eel Israafeel Munkar NakeerDocument4 pagesLearning About The Angels: Jibreel Meekaa'eel Israafeel Munkar NakeerErna Karlinna D. YanthyPas encore d'évaluation

- Article Dede Korkut Ki̇tabiDocument12 pagesArticle Dede Korkut Ki̇tabimetinbosnakPas encore d'évaluation

- Swami Dayananda Saraswati-The Spiritual, Philosophical and Social HeroDocument8 pagesSwami Dayananda Saraswati-The Spiritual, Philosophical and Social HeroLife HistoryPas encore d'évaluation