Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

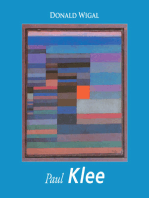

Paul Klee Fuga Enrojo

Transféré par

Ernesto0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

65 vues3 pagesAnalisis de Paul Klee-Musica y pintura

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentAnalisis de Paul Klee-Musica y pintura

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

65 vues3 pagesPaul Klee Fuga Enrojo

Transféré par

ErnestoAnalisis de Paul Klee-Musica y pintura

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 3

Paul Klee: Fugue in Red

Paul Klee (1879-1940) craved

the freedom to explore radical and modernist experimentations in his

paintings. In music, however, he could never come to terms with

contemporary works of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. In fact, he

even disliked the compositions of Wagner, Bruckner and Mahler. Klee

was a gifted musician who studied voice, piano, organ and violin at

the Stuttgart Conservatory. At age 11, he became a member of the

violin section of the Bern Music Association, and was on track for a

professional musical career. Yet during his teenage years, Klee

decided to focus on the visual arts because he found the idea of

going in for music creatively not particularly attractive in view of the

decline in the history of musical achievement. For Klee, modern

music lacked meaning, and he believed that the ultimate greatness of

Bach and Mozart could never be reproduced in the musical medium.

For Klee, the music of Bach and Mozart was the essential key to the

mysteries of creation. Both composers, according to Klee, aspired to

the notion of universality. Their musical compositions hold appeal for

everyone, the connoisseur, the professional and the amateur. Since

music in the 20th century had lost this sense of universality, Klee

envisioned an art of the future, which translated the musical

accomplishments of Bach and Mozart into visual terms. Klee became

intensely preoccupied with the parallels between music and painting,

and in his opinion rhythm was an important link between the two

genres, capable of illustrating temporal movements in both.

Theoretically, the philosopher and social critic Theodore Adorno had

described these points of convergence between music and painting,

but practically, it was Paul Klees work that visually revealed the

points of contact between two different art forms.

Credit: http://bauhaus-online.de/

Klee perceived a clear visual connection to the structural articulations

found in music. Focusing on polyphony and counterpoint, Klee

produced his watercolor Fugue in Red in 1921. This early attempt to

achieve a synthesis between music and art exposes a number of

floating forms, either figurative or as abstract derivations.

Overlapping shapes float over a two-dimensional surface, with the

temporal aspect graphically represented by a gradual shift in color.

Moving from the dark background to maximum transparency, the

visualized counterpoint combines in a cosmic harmony that reaches

towards a new sense of spirituality. Although essentially structural in

approach, this painting embodies Klees believe in harmony,

autonomy, and universality in humankind. As a musician and a

painter, Klee essentially created a harmonious arrangement that

echoes a universal order.

For the novelist Wilhelm Hausenstein, Klees attitude is immediately

understandable for musical people. Klee is one of the most

delightsome violinists, playing Bach and Mozart, who ever walked on

earth. For Klee, the musical world became his companion, possibly

even a part of his art. Given the ease with which Klee moved

between artistic worlds, it is hardly surprising that a number of

composers have musically encoded his paintings as well. Among

them, Peter Maxwell Davies, Harrison Birtwistle, Edison Denisov and

Tru Takemitsu, to name only a selected few. On occasion, you can

still hear Gunther Schullers Seven Studies on Klee Pictures performed

on stage. Composed in 1959, the work is located halfway between

jazz and classical music. Each of the seven pieces bears a slightly

different relationship to the original Klee picture from which it stems,

Schuller wrote. Some relate to the actual design, shape, or color

scheme of the painting, while others take the general mode of the

picture or its title as a point of departure. The music of Bach and

Mozart has inspired some of the most progressive art of our time, and

artists like Paul Klee devoted their lives to translate this universal

music into the language of visual art.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Cohen Birgid - Stefan Wolpe and The Avant-Garde DiasporaDocument342 pagesCohen Birgid - Stefan Wolpe and The Avant-Garde DiasporaMUSIK MEISTERPas encore d'évaluation

- Wolpe, Composer PDFDocument4 pagesWolpe, Composer PDFfakeiaeePas encore d'évaluation

- 2637 2528 Quarta 6 Druk PDFDocument16 pages2637 2528 Quarta 6 Druk PDFKhawlaAzizPas encore d'évaluation

- Pure Mime of Etienne DecrouxDocument9 pagesPure Mime of Etienne DecrouxFlorin StoianPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Film MusicDocument8 pagesWhat Is Film MusicKaslje ApusiPas encore d'évaluation

- Jennifer Shaw and Joseph Auner - The Cambridge Companion To Schoenberg (2010) - Pages-DeletedDocument28 pagesJennifer Shaw and Joseph Auner - The Cambridge Companion To Schoenberg (2010) - Pages-DeletedJulio BacaPas encore d'évaluation

- Painting MusicDocument12 pagesPainting MusicHumberto Virgüez100% (1)

- From Music To Sound Art: Soundscapes of The 21st CenturyDocument12 pagesFrom Music To Sound Art: Soundscapes of The 21st CenturyAlex YiuPas encore d'évaluation

- (P30-40) PanzerbeobachDocument11 pages(P30-40) Panzerbeobachsdcurlee75% (4)

- RETI RUDOLPH Tonality in Modern Music PDFDocument202 pagesRETI RUDOLPH Tonality in Modern Music PDFNabernoe0% (1)

- Ceramic TilesDocument19 pagesCeramic Tilesbarupatty50% (2)

- Boulez - Structures Book 1A AnalisysDocument6 pagesBoulez - Structures Book 1A AnalisysGisela PeláezPas encore d'évaluation

- Pablo Picasso - John W. Selfridge 1994Document112 pagesPablo Picasso - John W. Selfridge 1994Ynnodus100% (2)

- Gould1964a PDFDocument27 pagesGould1964a PDFIgor Reina100% (1)

- 20th Century MusicDocument5 pages20th Century MusicDavidPas encore d'évaluation

- Painting Music-Rhythm and Movement in ArtDocument13 pagesPainting Music-Rhythm and Movement in ArtMaria Melusine100% (1)

- Aspects of The Relationship Between Music and PaintingDocument7 pagesAspects of The Relationship Between Music and PaintingNarayan TimalsenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Spairality of Weft Knit FabricDocument5 pagesSpairality of Weft Knit FabricObak Prithibi100% (1)

- Murail, Tristan - Scelsi, De-ComposerDocument8 pagesMurail, Tristan - Scelsi, De-ComposerJuan Andrés Palacios100% (2)

- Cook PDFDocument9 pagesCook PDFspinalzo100% (1)

- Bach and Numerology: 'Dry Mathematical Stuff'?: DavidDocument23 pagesBach and Numerology: 'Dry Mathematical Stuff'?: DavidMarius BahneanPas encore d'évaluation

- Brothers AmatiDocument7 pagesBrothers AmatiPHilNam100% (1)

- In-Between Painting and MusicDocument24 pagesIn-Between Painting and MusicSinan Samanlı100% (1)

- Traditional Methods of Pattern Designing 1910 PDFDocument368 pagesTraditional Methods of Pattern Designing 1910 PDFEmile Mardacany100% (1)

- Boulez, Pierre (With) - The Man Who Would Be King - An Interview With Boulez (1993 Carvin)Document8 pagesBoulez, Pierre (With) - The Man Who Would Be King - An Interview With Boulez (1993 Carvin)Adriana MartelliPas encore d'évaluation

- Schönberg Escritos SobreDocument24 pagesSchönberg Escritos Sobrebraulyo2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Blad PDFDocument18 pagesBlad PDFJulian Guerrero100% (2)

- Alvar Aalto HousesDocument12 pagesAlvar Aalto HousesJules CornotPas encore d'évaluation

- Paul Klee Structural AnalogiesDocument2 pagesPaul Klee Structural AnalogiesSeckin MadenPas encore d'évaluation

- Jack ADocument3 pagesJack AalexhwangPas encore d'évaluation

- This Content Downloaded From 82.49.44.75 On Sun, 28 Feb 2021 13:32:47 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 82.49.44.75 On Sun, 28 Feb 2021 13:32:47 UTCPatrizia MandolinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cornelius CardewDocument10 pagesCornelius CardewIvan Eiji Yamauchi SimurraPas encore d'évaluation

- Música ConceptualDocument22 pagesMúsica Conceptualjordi_f_sPas encore d'évaluation

- Holm-Hudson Kucinskas CIM04 ProceedingsDocument9 pagesHolm-Hudson Kucinskas CIM04 ProceedingsAna CancelaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Priest of BeautyDocument16 pagesThe Priest of Beautyrhuticarr100% (1)

- Schoenberg TchaikovskyDocument2 pagesSchoenberg TchaikovskyAnonymous J5vpGuPas encore d'évaluation

- Lilienfeld, Yıl Belli DeğilDocument27 pagesLilienfeld, Yıl Belli DeğilMeriç EsenPas encore d'évaluation

- Mahnkopf Musical Modernity. From Classical Modernity Up To The Second Modernity Provisional Considerations PDFDocument13 pagesMahnkopf Musical Modernity. From Classical Modernity Up To The Second Modernity Provisional Considerations PDFlinushixPas encore d'évaluation

- Katschthaler MusicasTheatreDocument21 pagesKatschthaler MusicasTheatreNazareno NigrettiPas encore d'évaluation

- rg2 20th CenturyDocument8 pagesrg2 20th Centuryapi-253965377Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Origins of String QuartetsDocument4 pagesThe Origins of String Quartetsmikecurtis1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Boulez InterviewDocument7 pagesBoulez Interviewumayrh@gmail.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Schenker's Major Work ReleasedDocument3 pagesSchenker's Major Work ReleasedAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Tabula Rasa-EstheticsDocument16 pagesTabula Rasa-EstheticsBaran AytacPas encore d'évaluation

- An Apprenticeship and Its Stocktakings Leibowitz Boulez Messiaen and The Discourse and Practice of New MusicDocument23 pagesAn Apprenticeship and Its Stocktakings Leibowitz Boulez Messiaen and The Discourse and Practice of New MusicimanidaniellePas encore d'évaluation

- Fauvism and Expressnism The Creative Intuition PDFDocument6 pagesFauvism and Expressnism The Creative Intuition PDFCasswise ContentCreationPas encore d'évaluation

- FNGR 2019-2 Bonsdorff Anna-Maria Von Article1 1Document8 pagesFNGR 2019-2 Bonsdorff Anna-Maria Von Article1 1Joanie GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Hubert DamischDocument3 pagesHubert DamischLaura TPas encore d'évaluation

- Music Since The First World WarDocument17 pagesMusic Since The First World War8stringsofhellPas encore d'évaluation

- The Religious Music of The Twentieth and Twenty-First CenturiesDocument23 pagesThe Religious Music of The Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuriesmanuel1971Pas encore d'évaluation

- Paul Klee: 1 Early Life and TrainingDocument18 pagesPaul Klee: 1 Early Life and TrainingTimónPas encore d'évaluation

- Stravinsky-Auden EssayDocument17 pagesStravinsky-Auden EssayValjeanPas encore d'évaluation

- MusicalModernism AbstractsDocument15 pagesMusicalModernism Abstractsciprian_tutuPas encore d'évaluation

- Renata Skupin - Giacinto Scelsi - Homo ViatorDocument23 pagesRenata Skupin - Giacinto Scelsi - Homo ViatorDaniel FuchsPas encore d'évaluation

- Five Uncertain Situations (PQMC/GHMP) - Programme BrochureDocument16 pagesFive Uncertain Situations (PQMC/GHMP) - Programme BrochureIan MikyskaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rudolph Reti PDFDocument3 pagesRudolph Reti PDFfrank orozcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Current - Musicology.55.macdonald.24 55Document32 pagesCurrent - Musicology.55.macdonald.24 55Yang Yang CaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Original Production of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein's: Four Saints in Three ActsDocument16 pagesOriginal Production of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein's: Four Saints in Three ActsJared RedmondPas encore d'évaluation

- MAPEH ReviewerDocument12 pagesMAPEH ReviewerCassandra Jeurice UyPas encore d'évaluation

- Stravinsky PaperDocument5 pagesStravinsky Paperapi-398572298Pas encore d'évaluation

- Music 10 - Quarter 1Document41 pagesMusic 10 - Quarter 1Icy PPas encore d'évaluation

- IMPRESSIONIMDocument5 pagesIMPRESSIONIMAngela GanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Fowlers of Two Revolutionary War PatriotsDocument3 pagesFowlers of Two Revolutionary War PatriotsHerman KarlPas encore d'évaluation

- The Art of Ancient India - 12Document58 pagesThe Art of Ancient India - 12api-19731771Pas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Medieval Art2Document37 pages5 Medieval Art2Crystal Gale DavinPas encore d'évaluation

- Bredekamp, Horst 2003 Art History As BildwissenschaftDocument12 pagesBredekamp, Horst 2003 Art History As BildwissenschaftMitchell JohnsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Porter BerthaDocument5 pagesPorter BerthaMohamed AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Art Appreciation - Lesson 4 Activity Google ResearchDocument1 pageArt Appreciation - Lesson 4 Activity Google ResearchClaro M. GarchitorenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Goharshad Mosque PlanDocument3 pagesGoharshad Mosque PlanKatPas encore d'évaluation

- Allan Braham - The Architecture of The French EnlightenmentDocument289 pagesAllan Braham - The Architecture of The French EnlightenmentDaniela Andreea PredaPas encore d'évaluation

- Paintings of Juan LunaDocument17 pagesPaintings of Juan LunaGerald SolisPas encore d'évaluation

- Lumad SculptureDocument4 pagesLumad Sculpture789scribdaccountPas encore d'évaluation

- Indiana Jones and The Fate of Atlantis WALKTHROUGHDocument14 pagesIndiana Jones and The Fate of Atlantis WALKTHROUGHkanttiPas encore d'évaluation

- ProductskatalogDocument73 pagesProductskatalogotari1774Pas encore d'évaluation

- You Want A Confederate Monument My Body Is A Confederate MonumentDocument4 pagesYou Want A Confederate Monument My Body Is A Confederate MonumentmusabPas encore d'évaluation

- Hair Combs OLA204 - Ashton-LibreDocument32 pagesHair Combs OLA204 - Ashton-LibreAsma MahdyPas encore d'évaluation

- Buddhist ArchitectureDocument8 pagesBuddhist ArchitectureKaushik JayaveeranPas encore d'évaluation

- Arts & Globalization Platform 2019: 'Politics of Space'Document22 pagesArts & Globalization Platform 2019: 'Politics of Space'Rikke JørgensenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Essential Body - Mesopotamian Conception of The Gendered BodyDocument7 pagesThe Essential Body - Mesopotamian Conception of The Gendered BodyKavi kPas encore d'évaluation

- Craft and Creative Media Mosaic Power Point Chap 7Document7 pagesCraft and Creative Media Mosaic Power Point Chap 7Sarah Lyn White-CantuPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice 2 Costa Rican ArtDocument21 pagesPractice 2 Costa Rican ArtJefry Arguello ZuñigaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 4 - Rennaissance and ManneristDocument86 pagesUnit 4 - Rennaissance and Manneristsarath sarathPas encore d'évaluation

- Pastel HistoryDocument3 pagesPastel HistoryfernandocomedoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Art and Science of Facial EstheticsDocument22 pagesArt and Science of Facial EstheticsDiego SolaquePas encore d'évaluation