Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Sacred Cow Response

Transféré par

pianoplayer7242Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Sacred Cow Response

Transféré par

pianoplayer7242Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Bryan Luu

Dr. Monteiro

Soc 100

Eastern University

Cow reverence has long since been a cultural norm in most of India

where there is a dense Hindu population. In some regions it is against the

law to slaughter cows. Even during times when food is scarce and people

are barely surviving with the resources they have, cows are still not used for

food. Essentially, spiritual values are prioritized over human life. Many

people, especially in the Western hemisphere, see this ideology as

nonsensical and inefficient. However, anthropologist Marvin Harris, argues

that cows play a much bigger role in Indian society than simply a religious

icon.

It is important to note that Indian society runs largely on agriculture as

a sustaining source of food. Since tractors and other modern farming tools

are lacking in India, cattle are the primary vehicle of working the field.

Farmers use oxen and bulls to plow, seed, and harvest their fields. If his

animal dies, the farmer essentially has no tools with which to farm. He

cannot eat; he cannot feed his family, and he cannot make any income.

Female cows are held to an even higher position than bulls because they can

produce more oxen or bulls. Though the cattle population is large, there are

still not enough cattle to service Indias 70 million farms. In addition to being

an agricultural need, cattle provide both fertilizer and energy fuel through

their dung. Indian cattle return 17% of the energy they consumer compared

to the meager 4% from US cattle. For this reason, nearly 100% of cattle

dung is recovered in India. Harris emphasizes that if India switched from

natural fertilizer to commercial fertilizer and coal, expenses would rise by a

huge factor. In this perspective, cows are important for the survival of the

Indian family through agriculture and provide fertilizer and fuel in an

affordable manner.

The reality of Indian peoples dependence on cows highlights why the

cow is sacred. Harris writes, Like all concepts of the sacred and profane,

this one affects the physical world; it defines the relationships that are

important for the maintenance of Indian society (p10). Dysfunction

concerning the cow also means dysfunction concerning the people. Not only

is the cow directly involved within Indian society, it plays a role in their

identity as a Hindu people as well. Hindu India was once invaded by a

Muslim nation in 800 A.D.; in efforts to separate themselves from the

invaders, they took pride and emphasis in their restriction of beef eating,

going against the culture of their invaders. Events like these illustrate how

the cow is significant in Indian individualism and how that further builds upon

its sacredness.

In terms of ethnocentrism and cultural relativism, this article is inclined

more to the side relativism than ethnocentrism. The author opens by stating

how most westerners view the Indian culture as illogical and

counterproductive. However, he rebukes that statement by explaining how it

is a surface level observation and fails to show true understanding of the

Indian way of life. At this point in the article, the author switches over to a

cultural relativistic lens in which he describes cows as how natives see them.

He describes native interactions with the cow as opposed to a foreigners.

Rather than a sense of counter-productivity, the reader begins to empathize

and sees reason for the sacredness of the cow. On the other hand, the

ethnocentric view of the Westerners portrays Indian society negatively to the

reader. Because ethnocentrism comes with a biasness that often prevent

deeper understandingas demonstrated in this articleit is clear why the

sociologist prefers to understand cultures based on their own unique terms

and experiences.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Social DemographyD'EverandSocial DemographyKarl E. TaeuberPas encore d'évaluation

- Knowledge and Power in Morocco: The Education of a Twentieth-Century NotableD'EverandKnowledge and Power in Morocco: The Education of a Twentieth-Century NotableÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2)

- A Necessary Engagement: Reinventing America's Relations with the Muslim WorldD'EverandA Necessary Engagement: Reinventing America's Relations with the Muslim WorldÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (1)

- We Were Adivasis: Aspiration in an Indian Scheduled TribeD'EverandWe Were Adivasis: Aspiration in an Indian Scheduled TribePas encore d'évaluation

- Conservation in a Crowded World: Case studies from the Asia-PacificD'EverandConservation in a Crowded World: Case studies from the Asia-PacificPas encore d'évaluation

- Syesis: Vol. 8, Supplement 1: Vegetation and Environment of the Coastal Western Hemlock Zone in Strathcona Provincial Park, British Columbia, CanadaD'EverandSyesis: Vol. 8, Supplement 1: Vegetation and Environment of the Coastal Western Hemlock Zone in Strathcona Provincial Park, British Columbia, CanadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Copts and the Security State: Violence, Coercion, and Sectarianism in Contemporary EgyptD'EverandCopts and the Security State: Violence, Coercion, and Sectarianism in Contemporary EgyptPas encore d'évaluation

- Paradoxes of the Popular: Crowd Politics in BangladeshD'EverandParadoxes of the Popular: Crowd Politics in BangladeshPas encore d'évaluation

- Unity and Diversity in World’S Living Religions: A Compact SurveyD'EverandUnity and Diversity in World’S Living Religions: A Compact SurveyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Food Question in the Middle East: Cairo Papers in Social Science Vol. 34, No. 4D'EverandThe Food Question in the Middle East: Cairo Papers in Social Science Vol. 34, No. 4Malak S. RouchdyPas encore d'évaluation

- God in the Tumult of the Global Square: Religion in Global Civil SocietyD'EverandGod in the Tumult of the Global Square: Religion in Global Civil SocietyPas encore d'évaluation

- Politics of Indigeneity: Challenging the State in Canada and Aotearoa New ZealandD'EverandPolitics of Indigeneity: Challenging the State in Canada and Aotearoa New ZealandÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Sources of Indian Traditions: Modern India, Pakistan, and BangladeshD'EverandSources of Indian Traditions: Modern India, Pakistan, and BangladeshPas encore d'évaluation

- The Vanished Imam: Musa al Sadr and the Shia of LebanonD'EverandThe Vanished Imam: Musa al Sadr and the Shia of LebanonÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (5)

- A Social Revolution: Politics and the Welfare State in IranD'EverandA Social Revolution: Politics and the Welfare State in IranPas encore d'évaluation

- Islamic Divorce in the Twenty-First Century: A Global PerspectiveD'EverandIslamic Divorce in the Twenty-First Century: A Global PerspectiveErin E. StilesPas encore d'évaluation

- Coming of Age in Medieval Egypt: Female Adolescence, Jewish Law, and Ordinary CultureD'EverandComing of Age in Medieval Egypt: Female Adolescence, Jewish Law, and Ordinary CulturePas encore d'évaluation

- Claiming the Oriental Gateway: Prewar Seattle and Japanese AmericaD'EverandClaiming the Oriental Gateway: Prewar Seattle and Japanese AmericaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Great Social Laboratory: Subjects of Knowledge in Colonial and Postcolonial EgyptD'EverandThe Great Social Laboratory: Subjects of Knowledge in Colonial and Postcolonial EgyptPas encore d'évaluation

- Exile and the Nation: The Parsi Community of India & the Making of Modern IranD'EverandExile and the Nation: The Parsi Community of India & the Making of Modern IranPas encore d'évaluation

- Selective Remembrances: Archaeology in the Construction, Commemoration, and Consecration of National PastsD'EverandSelective Remembrances: Archaeology in the Construction, Commemoration, and Consecration of National PastsPas encore d'évaluation

- The New Food Activism: Opposition, Cooperation, and Collective ActionD'EverandThe New Food Activism: Opposition, Cooperation, and Collective ActionAlison AlkonPas encore d'évaluation

- Islamic Modern: Religious Courts and Cultural Politics in MalaysiaD'EverandIslamic Modern: Religious Courts and Cultural Politics in MalaysiaÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- Modernity and Culture from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, 1890--1920D'EverandModernity and Culture from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, 1890--1920Évaluation : 1 sur 5 étoiles1/5 (1)

- The Making of Southeast Asia: International Relations of a RegionD'EverandThe Making of Southeast Asia: International Relations of a RegionPas encore d'évaluation

- Eleven Great Religions of the World Today: A Quick DescriptionD'EverandEleven Great Religions of the World Today: A Quick DescriptionPas encore d'évaluation

- Strangers in the World: Multireligious Reflections on ImmigrationD'EverandStrangers in the World: Multireligious Reflections on ImmigrationHussam S. TimaniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Quest for God and the Good: World Philosophy as a Living ExperienceD'EverandThe Quest for God and the Good: World Philosophy as a Living ExperiencePas encore d'évaluation

- Precarity and Belonging: Labor, Migration, and NoncitizenshipD'EverandPrecarity and Belonging: Labor, Migration, and NoncitizenshipPas encore d'évaluation

- Aztec Empire: A Brief History from Beginning to the EndD'EverandAztec Empire: A Brief History from Beginning to the EndPas encore d'évaluation

- Family Activism: Immigrant Struggles and the Politics of NoncitizenshipD'EverandFamily Activism: Immigrant Struggles and the Politics of NoncitizenshipPas encore d'évaluation

- Dreams Made Small: The Education of Papuan Highlanders in IndonesiaD'EverandDreams Made Small: The Education of Papuan Highlanders in IndonesiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Extreme Longevity: Discovering Earth's Oldest OrganismsD'EverandExtreme Longevity: Discovering Earth's Oldest OrganismsPas encore d'évaluation

- Making and Unmaking Public Health in Africa: Ethnographic and Historical PerspectivesD'EverandMaking and Unmaking Public Health in Africa: Ethnographic and Historical PerspectivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Dilemmas of Modernity: Bolivian Encounters with Law and LiberalismD'EverandDilemmas of Modernity: Bolivian Encounters with Law and LiberalismPas encore d'évaluation

- Pride and Produce: The Origin, Evolution, and Survival of the Drowned Lands, the Hudson ValleyD'EverandPride and Produce: The Origin, Evolution, and Survival of the Drowned Lands, the Hudson ValleyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Deoband Madrassah Movement: Countercultural Trends and TendenciesD'EverandThe Deoband Madrassah Movement: Countercultural Trends and TendenciesÉvaluation : 1 sur 5 étoiles1/5 (1)

- Revolutions and Rebellions in Afghanistan: Anthropological PerspectivesD'EverandRevolutions and Rebellions in Afghanistan: Anthropological PerspectivesM. Nazif ShahraniPas encore d'évaluation

- Compassionate Communalism: Welfare and Sectarianism in LebanonD'EverandCompassionate Communalism: Welfare and Sectarianism in LebanonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Palestinian-Arab Citizens of Israel: Towards the Internationalisation of National AspirationsD'EverandThe Palestinian-Arab Citizens of Israel: Towards the Internationalisation of National AspirationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Marginalizing Access to the Sustainable Food System: An Examination of Oakland's Minority DistrictsD'EverandMarginalizing Access to the Sustainable Food System: An Examination of Oakland's Minority DistrictsPas encore d'évaluation

- Everyday Occupations: Experiencing Militarism in South Asia and the Middle EastD'EverandEveryday Occupations: Experiencing Militarism in South Asia and the Middle EastPas encore d'évaluation

- SN2285 Individual Assignment A0192262H TD3 LakshmiDocument7 pagesSN2285 Individual Assignment A0192262H TD3 LakshmiLakshmi AnnamalaiPas encore d'évaluation

- After A Century and A Quarter by G.S GhuryeDocument185 pagesAfter A Century and A Quarter by G.S Ghuryenrk1962100% (1)

- Bomb Calorimetry LabDocument8 pagesBomb Calorimetry Labpianoplayer7242100% (1)

- Thermo Lab Report3Document2 pagesThermo Lab Report3pianoplayer7242Pas encore d'évaluation

- Multistep Synthesis Lab ReportDocument1 pageMultistep Synthesis Lab Reportpianoplayer72420% (1)

- Bryan Luu Mike AxlerDocument1 pageBryan Luu Mike Axlerpianoplayer7242Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gulliver's Travels Literary Analysis - DraftDocument6 pagesGulliver's Travels Literary Analysis - Draftpianoplayer7242Pas encore d'évaluation

- Monuments Men PaperDocument4 pagesMonuments Men Paperpianoplayer7242Pas encore d'évaluation

- Literary Analysis - A Valediction Forbidding Mourning - John DonneDocument4 pagesLiterary Analysis - A Valediction Forbidding Mourning - John Donnepianoplayer7242Pas encore d'évaluation

- Senior Class Trip: Rancocas Valley Regional High SchoolDocument22 pagesSenior Class Trip: Rancocas Valley Regional High Schoolpianoplayer7242Pas encore d'évaluation

- LapodedeDocument12 pagesLapodedemanmohankamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dairy DevelopmentDocument100 pagesDairy DevelopmentidkrishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gaushala and Recommendations of TheDocument10 pagesGaushala and Recommendations of TheDr. Madhu D.N.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Eng Q2 Week 5 D1-5Document68 pagesEng Q2 Week 5 D1-5Laar MarquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Farm Guidelines For Mastitis ControlDocument128 pagesFarm Guidelines For Mastitis ControlShankar Shete0% (1)

- Analysis of Brand Promotions and Successful Marketing Strategies of Parag Milk FoodsDocument20 pagesAnalysis of Brand Promotions and Successful Marketing Strategies of Parag Milk FoodsMandar mahadikPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Agricultural Engineering Standard Paes 407:2001 Agricultural Structures - Housing For Dairy CattleDocument10 pagesPhilippine Agricultural Engineering Standard Paes 407:2001 Agricultural Structures - Housing For Dairy Cattlejoselito dumdumPas encore d'évaluation

- ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute Journal of Southeast Asian EconomiesDocument16 pagesISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute Journal of Southeast Asian Economiesadhissl2013Pas encore d'évaluation

- Beef Eating in The Ancient Tamizhagam - K. V. Ramakrishna RaoDocument10 pagesBeef Eating in The Ancient Tamizhagam - K. V. Ramakrishna Raoanjana nPas encore d'évaluation

- Cow: State Cattle: Animal of Haryana - Smt. Sukanya BerwalDocument17 pagesCow: State Cattle: Animal of Haryana - Smt. Sukanya BerwalNaresh KadyanPas encore d'évaluation

- NSTP2 Output 1Document38 pagesNSTP2 Output 1Save The Day SuppliesPas encore d'évaluation

- Role and Responsibilities of Livestock Sector in Poverty2Document18 pagesRole and Responsibilities of Livestock Sector in Poverty2Sunil GamagePas encore d'évaluation

- Feed Composition T AbleDocument11 pagesFeed Composition T AbleallleeexxxPas encore d'évaluation

- Meatirxtrilogyquestions 1Document2 pagesMeatirxtrilogyquestions 1api-330049990Pas encore d'évaluation

- LED Investment Plan FinalDocument40 pagesLED Investment Plan FinalAlfredPas encore d'évaluation

- 16Document34 pages16admin2146Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lab Manual - FST4924Document31 pagesLab Manual - FST4924Faatimah ShameemahPas encore d'évaluation

- Bovine Mastitis PDFDocument34 pagesBovine Mastitis PDFMamtaPas encore d'évaluation

- Farm Size Factor Productivity and Returns To ScaleDocument8 pagesFarm Size Factor Productivity and Returns To ScaleAkshay YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Meal MasterDocument4 pagesMeal MasterUri DrachPas encore d'évaluation

- Dairy JudgingDocument35 pagesDairy JudgingSimon Jasper J. AmantePas encore d'évaluation

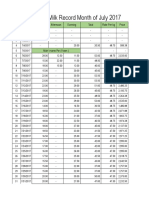

- Milk Record Month of July 2017: Sno Date Morning Afternoon Evening Total Rate Per KG PriceDocument6 pagesMilk Record Month of July 2017: Sno Date Morning Afternoon Evening Total Rate Per KG PriceRab Nawaz KathiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fertility and Hair Coat Characteristics of Holstein Cows in A Tropical EnvironmentDocument8 pagesFertility and Hair Coat Characteristics of Holstein Cows in A Tropical EnvironmentSaifuddin HaswarePas encore d'évaluation

- Breeds of CattleDocument5 pagesBreeds of CattleLeah Hope CedroPas encore d'évaluation

- Affections of HornDocument28 pagesAffections of HornNaveen BasudePas encore d'évaluation

- Agricultural Development Strategy OverviewDocument10 pagesAgricultural Development Strategy OverviewMel ColsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Polyface-The Farm of Many Faces: Case AnalysisDocument9 pagesPolyface-The Farm of Many Faces: Case AnalysisjackPas encore d'évaluation

- March 31, 2015 Central Wisconsin ShopperDocument24 pagesMarch 31, 2015 Central Wisconsin ShoppercwmediaPas encore d'évaluation

- HF CowDocument13 pagesHF Cowkarishma10Pas encore d'évaluation

- Barn SnitationDocument12 pagesBarn SnitationDr MaroofPas encore d'évaluation