Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Addl Cases

Transféré par

imXinYCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Addl Cases

Transféré par

imXinYDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Mirasol vs.

DPWH

Facts: On 19 February 1968, Secretary Antonio V. Raquiza of the

Department of Public Works and Communications issued AO 1,

which, among others, prohibited motorcycles on limited access

highways. Accordingly, petitioners filed an Amended Petition on

February 8, 2001 wherein petitioners sought the declaration of

nullity of the aforesaid administrative issuances. Moreover,

petitioners prayed for the issuance of a temporary restraining order

and/or preliminary injunction to prevent the enforcement of the

total ban on motorcycles along the entire breadth of North and

South Luzon Expressways and the Manila-Cavite (Coastal Road) Toll

Expressway under DO 215.

Issue: Is DPWH Administrative Order No.1, DO 74 violative of the

right to travel? Are all motorized vehicles created equal?

Held: DO 74 and DO 215 are void because the DPWH has no

authority to declare certain expressways as limited access facilities.

Under the law, it is the DOTC which is authorized to administer and

enforce all laws, rules and regulations in the field of transportation

and to regulate related activities. The DPWH cannot delegate a

power or function which it does not possess in the first place.

We find that it is neither warranted nor reasonable for petitioners to

say that the only justifiable classification among modes of transport

is the motorized against the non-motorized. Not all motorized

vehicles are created equal. A 16-wheeler truck is substantially

different from other light vehicles. The first may be denied access

to some roads where the latter are free to drive. Old vehicles may

be reasonably differentiated from newer models.46 We find that

real and substantial differences exist between a motorcycle and

other forms of transport sufficient to justify its classification among

those prohibited from plying the toll ways. Amongst all types of

motorized transport, it is obvious, even to a child, that a motorcycle

is quite different from a car, a bus or a truck. The most obvious and

troubling difference would be that a two-wheeled vehicle is less

stable and more easily overturned than a four-wheeled vehicle.

Police Power

City of Manila v. Judge Laguio

On 30 Mar 1993, Mayor Lim signed into law Ordinance No. 7783

entitled AN ORDINANCE PROHIBITING THE ESTABLISHMENT OR

OPERATION OF BUSINESSES PROVIDING CERTAIN FORMS OF

AMUSEMENT, ENTERTAINMENT, SERVICES AND FACILITIES IN THE

ERMITA-MALATE AREA, PRESCRIBING PENALTIES FOR VIOLATION

THEREOF, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES. It basically prohibited

establishments such as bars, karaoke bars, motels and hotels from

operating in the Malate District which was notoriously viewed as a

red light district harboring thrill seekers. Malate Tourist

Development Corporation avers that the ordinance is invalid as it

includes hotels and motels in the enumeration of places offering

amusement or entertainment. MTDC reiterates that they do not

market such nor do they use women as tools for entertainment.

MTDC also avers that under the LGC, LGUs can only regulate

motels but cannot prohibit their operation. The City reiterates that

the Ordinance is a valid exercise of Police Power as provided as well

in the LGC. The City likewise emphasized that the purpose of the

law is to promote morality in the City.

ISSUE: Whether or not Ordinance 7783 is valid.

HELD: The SC ruled that the said Ordinance is null and void. The

SC noted that for an ordinance to be valid, it must not only be

within the corporate powers of the local government unit to enact

and must be passed according to the procedure prescribed by law,

it must also conform to the following substantive requirements:

(1) must not contravene the Constitution or any statute;

(2) must not be unfair or oppressive;

(3) must not be partial or discriminatory;

(4) must not prohibit but may regulate trade;

(5) must be general and consistent with public policy; and

(6) must not be unreasonable.

The police power of the City Council, however broad and farreaching, is subordinate to the constitutional limitations thereon;

and is subject to the limitation that its exercise must be reasonable

and for the public good. In the case at bar, the enactment of the

Ordinance was an invalid exercise of delegated power as it is

unconstitutional and repugnant to general laws.

Tuason v. Register of Deeds

FACTS:

Petitioners bought in 1965 from Carmel Farms Inc. a piece of land in

Caloocan City by virtue of which they were issued a title in their

names and they took possession of their property. In 1973,

President Marcos, exercising martial law powers, issued PD 293

cancelling the certificates of titles of Carmel Farms and declaring

the lands covered to be open for disposition and sale to members

of the Malacaang Association Inc.

ISSUE: W/N the President has the power to cancel certificates of

titles

HELD:

The Decree reveals that Mr. Marcos exercised an obviously judicial

function. Since he was never vested with judicial power -- such

power, as everyone knows, being vested in the SC and such inferior

courts as may be established by law -- the judicial acts done by him

were under the circumstances alien to his office as chief executive.

OSMEA vs. ORBOS

GR No. 99886, March 31, 1993

" To avoid the taint of unlawful delegation of the power to tax, there

must be a standard which implies that the legislature determines

matter of principle and lays down fundamental policy."

FACTS:

Senator John Osmea assails the constitutionality of paragraph 1c

of PD 1956, as amended by EO 137, empowering the Energy

Regulatory Board (ERB) to approve the increase of fuel prices or

impose additional amounts on petroleum products which proceeds

shall accrue to the Oil Price Stabilization Fund (OPSF) established

for the reimbursement to ailing oil companies in the event of

sudden price increases. The petitioner avers that the collection on

oil products establishments is an undue and invalid delegation of

legislative power to tax. Further, the petitioner points out that since

a 'special fund' consists of monies collected through the taxing

power of a State, such amounts belong to the State, although the

use thereof is limited to the special purpose/objective for which it

was created. It thus appears that the challenge posed by the

petitioner is premised primarily on the view that the powers

granted to the ERB under P.D. 1956, as amended, partake of the

nature of the taxation power of the State.

ISSUE:

Is there an undue delegation of the legislative power of taxation?

HELD:

None. It seems clear that while the funds collected may be referred

to as taxes, they are exacted in the exercise of the police power of

the State. Moreover, that the OPSF as a special fund is plain from

the special treatment given it by E.O. 137. It is segregated from the

general fund; and while it is placed in what the law refers to as a

"trust liability account," the fund nonetheless remains subject to

the scrutiny and review of the COA. The Court is satisfied that these

measures comply with the constitutional description of a "special

fund." With regard to the alleged undue delegation of legislative

power, the Court finds that the provision conferring the authority

upon the ERB to impose additional amounts on petroleum products

provides a sufficient standard by which the authority must be

exercised. In addition to the general policy of the law to protect the

local consumer by stabilizing and subsidizing domestic pump rates,

P.D. 1956 expressly authorizes the ERB to impose additional

amounts to augment the resources of the Fund.

Lozano vs Martinez, G.R. No. L-63419, December 18, 1986

Facts:

Petitioners were charged with violation of Batas Pambansa Bilang

22 (Bouncing Check Law). They moved seasonably to quash the

informations on the ground that the acts charged did not constitute

an offense, the statute being unconstitutional. The motions were

denied by the respondent trial courts, except in one case, wherein

the trial court declared the law unconstitutional and dismissed the

case. The parties adversely affected thus appealed.

Issue:

1. Whether or not BP 22 is violative of the constitutional provision

on non-imprisonment due to debt;

2. Whether it impairs freedom of contract;

3. Whether it contravenes the equal protection clause.

Held:

1. The enactment of BP 22 is a valid exercise of the police power

and is not repugnant to the constitutional inhibition against

imprisonment for debt. The gravamen of the offense punished by

BP 22 is the act of making and issuing a worthless check or a check

that is dishonored upon its presentation for payment. It is not the

non-payment of an obligation which the law punishes. The law is

not intended or designed to coerce a debtor to pay his debt. The

thrust of the law is to prohibit, under pain of penal sanctions, the

making of worthless checks and putting them in circulation.

Because of its deleterious effects on the public interest, the

practice is proscribed by the law. The law punishes the act not as

an offense against property, but an offense against public order.

Unlike a promissory note, a check is not a mere undertaking to pay

an amount of money. It is an order addressed to a bank and

partakes of a representation that the drawer has funds on deposit

against which the check is drawn, sufficient to ensure payment

upon its presentation to the bank. There is therefore an element of

certainty or assurance that the instrument will be paid upon

presentation. For this reason, checks have become widely accepted

as a medium of payment in trade and commerce. Although not

legal tender, checks have come to be perceived as convenient

substitutes for currency in commercial and financial transactions.

The basis or foundation of such perception is confidence. If such

confidence is shaken, the usefulness of checks as currency

substitutes would be greatly diminished or may become nil. Any

practice therefore tending to destroy that confidence should be

deterred for the proliferation of worthless checks can only create

havoc in trade circles and the banking community.

The effects of the issuance of a worthless check transcends the

private interests of the parties directly involved in the transaction

and touches the interests of the community at large. The mischief it

creates is not only a wrong to the payee or holder, but also an

injury to the public. The harmful practice of putting valueless

commercial papers in circulation, multiplied a thousand fold, can

very wen pollute the channels of trade and commerce, injure the

banking system and eventually hurt the welfare of society and the

public interest.

2. The freedom of contract which is constitutionally protected is

freedom to enter into lawful contracts. Contracts which

contravene public policy are not lawful. Besides, we must bear in

mind that checks cannot be categorized as mere contracts. It is a

commercial instrument which, in this modem day and age, has

become a convenient substitute for money; it forms part of the

banking system and therefore not entirely free from the regulatory

power of the state.

3. There is no substance in the claim that the statute in question

denies equal protection of the laws or is discriminatory, since it

penalizes the drawer of the check, but not the payee. It is

contended that the payee is just as responsible for the crime as the

drawer of the check, since without the indispensable participation

of the payee by his acceptance of the check there would be no

crime. This argument is tantamount to saying that, to give equal

protection, the law should punish both the swindler and the

swindled. The petitioners posture ignores the well-accepted

meaning of the clause equal protection of the laws. The clause

does not preclude classification of individuals, who may be

accorded different treatment under the law as long as the

classification is not unreasonable or arbitrary.

Republic vs. Rosemoor

Republic of the Philippines vs. Rosemoor Mining and

Development Corporation, et al.

G.R. No. 149927 March 30, 2004

Panganiban, J.:

Facts: Petitioner Rosemoor Mining and Development Corporation

after having been granted permission to prospect for marble

deposits in the mountains of Biak-na-Bato, San Miguel, Bulacan,

succeeded in discovering marble deposits of high quality and in

commercial quantities in Mount Mabio which forms part of the Biakna-Bato mountain range.

The petitioner then applied with the Bureau of Mines, now Mines

and Geosciences Bureau, for the issuance of the corresponding

license to exploit said marble deposits.

License No. 33 was issued by the Bureau of Mines in favor of the

herein petitioners. Shortly thereafter, Respondent Ernesto Maceda

cancelled the petitioners license stating that their license had

illegally been issued, because it violated Section 69 of PD 463; and

that there was no more public interest served by the continued

existence or renewal of the license. The latter reason was

confirmed by the language of Proclamation No. 84. According to

this law, public interest would be served by reverting the parcel of

land that was excluded by Proclamation No. 2204 to the former

status of that land as part of the Biak-na-Bato national park.

Issue: Whether or not Presidential Proclamation No. 84 is valid.

Held: Yes. We cannot sustain the argument that Proclamation No.

84 is a bill of attainder; that is, a legislative act which inflicts

punishment without judicial trial. Its declaration that QLP No. 33 is

a patent nullity is certainly not a declaration of guilt. Neither is the

cancellation of the license a punishment within the purview of the

constitutional proscription against bills of attainder.

Too, there is no merit in the argument that the proclamation is an

ex post facto law. It is settled that an ex post facto law is limited in

its scope only to matters criminal in nature. Proclamation 84, which

merely restored the area excluded from the Biak-na-Bato national

park by canceling respondents license, is clearly not penal in

character.

Also at the time President Aquino issued Proclamation No. 84 on

March 9, 1987, she was still validly exercising legislative powers

under the Provisional Constitution of 1986. Section 1 of Article II of

Proclamation No. 3, which promulgated the Provisional Constitution,

granted her legislative power until a legislature is elected and

convened under a new Constitution. The grant of such power is also

explicitly recognized and provided for in Section 6 of Article XVII of

the 1987 Constitution.

JMM vs CA

Due to the death of one Maricris Sioson in 1991, Cory banned the

deployment of performing artists to Japan and other destinations.

This was relaxed however with the introduction of the

Entertainment Industry Advisory Council which later proposed a

plan to POEA to screen and train performing artists seeking to go

abroad. In pursuant to the proposal POEA and the secretary of

DOLE sought a 4 step plan to realize the plan which included an

Artists Record Book which a performing artist must acquire prior to

being deployed abroad. The Federation of Talent Managers of the

Philippines assailed the validity of the said regulation as it violated

the right to travel, abridge existing contracts and rights and

deprives artists of their individual rights. JMM intervened to bolster

the cause of FETMOP. The lower court ruled in favor of EIAC.

ISSUE: Whether or not the regulation by EIAC is valid.

HELD: The SC ruled in favor of the lower court. The regulation is a

valid exercise of police power. Police power concerns government

enactments which precisely interfere with personal liberty or

property in order to promote the general welfare or the common

good. As the assailed Department Order enjoys a presumed

validity, it follows that the burden rests upon petitioners to

demonstrate that the said order, particularly, its ARB requirement,

does not enhance the public welfare or was exercised arbitrarily or

unreasonably. The welfare of Filipino performing artists, particularly

the women was paramount in the issuance of Department Order

No. 3. Short of a total and absolute ban against the deployment of

performing artists to high risk destinations, a measure which

would only drive recruitment further underground, the new scheme

at the very least rationalizes the method of screening performing

artists by requiring reasonable educational and artistic skills from

them and limits deployment to only those individuals adequately

prepared for the unpredictable demands of employment as artists

abroad. It cannot be gainsaid that this scheme at least lessens the

room for exploitation by unscrupulous individuals and agencies.

1 UTAK VS COMELEC

GR 206020 April 14 2015

Facts:

In 2013, the COMELEC promulgated Resolution 9615 providing rules

that would implement Sec 9 of RA 9006 or the Fair Elections Act.

One of the provisions of the Resolution provide that the posting of

any election propaganda or materials during the campaign period

shall be prohibited in public utility vehicles (PUV) and within the

premises of public transport terminals. 1 UTAK, a party-list

organization, questioned the prohibition as it impedes the right to

free speech of the private owners of PUVs and transport terminals.

Issue 1: W/N the COMELEC may impose the prohibition on PUVs

and public transport terminals during the election pursuant to its

regulatory powers delegated under Art IX-C, Sec 4 of the

Constitution

No. The COMELEC may only regulate the franchise or permit to

operate and not the ownership per se of PUVs and transport

terminals. The posting of election campaign material on vehicles

used for public transport or on transport terminals is not only a

form of political expression, but also an act of ownership it has

nothing to do with the franchise or permit to operate the PUV or

transport terminal.

Issue 2: W/N the regulation is justified by the captive audience

doctrine

No. A government regulation based on the captive-audience

doctrine may not be justified if the supposed captive audience

may avoid exposure to the otherwise intrusive speech. Here, the

commuters are not forced or compelled to read the election

campaign materials posted on PUVs and transport terminals. Nor

are they incapable of declining to receive the messages contained

in the posted election campaign materials since they may simply

avert their eyes if they find the same unbearably intrusive. Hence,

the doctrine is not applicable.

Issue 3: W/N the regulation constitutes prior restraints on free

speech

Yes. It unduly infringes on the fundamental right of the people to

freedom of speech. Central to the prohibition is the freedom of

individuals such as the owners of PUVs and private transport

terminals to express their preference, through the posting of

election campaign material in their property, and convince others

to agree with them.

Issue 4: W/N the regulation is a valid content-neutral regulation

No. The prohibition under the certain provisions of RA 9615 are

content-neutral regulations since they merely control the place

where election campaign materials may be posted, but the

prohibition is repugnant to the free speech clause as it fails to

satisfy all of the requisites for a valid content-neutral regulation.

The restriction on free speech of owners of PUVs and transport

terminals is not necessary to a stated governmental interest. First,

while Resolution 9615 was promulgated by the COMELEC to

implement the provisions of Fair Elections Act, the prohibition on

posting of election campaign materials on PUVs and transport

terminals was not provided for therein. Second, there are more

than sufficient provisions in our present election laws that would

ensure equal time, space, and opportunity to candidates in

elections. Hence, one of the requisites of a valid content-neutral

regulation was not satisfied.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemD'EverandThe Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 61649 May 14, 1991 en Banc Paras, J.Document5 pagesG.R. No. 61649 May 14, 1991 en Banc Paras, J.Meah BrusolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 2 CasesDocument80 pagesConsti 2 CasesJillandroPas encore d'évaluation

- Police Power Case DigestDocument10 pagesPolice Power Case Digestalbert alonzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Police Power Case DigestsDocument3 pagesPolice Power Case Digestsaphrodatee75% (4)

- Consti Complete CasesDocument171 pagesConsti Complete CasesQueenVictoriaAshleyPrietoPas encore d'évaluation

- Bill of Rights Case DigestDocument95 pagesBill of Rights Case DigestAboy SantiagoPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Manila Vs LaguioDocument5 pagesCity of Manila Vs LaguioKhen Steven RoblesPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 2 Case DigestDocument74 pagesConsti 2 Case DigestPring SumPas encore d'évaluation

- Due Process of LawDocument11 pagesDue Process of LawLorelei B RecuencoPas encore d'évaluation

- Non-Delegation of Taxation PowerDocument4 pagesNon-Delegation of Taxation PowerCon PuPas encore d'évaluation

- Digest For Week 4Document12 pagesDigest For Week 4John Peter YrumaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine LiteratureDocument9 pagesPhilippine LiteratureisaiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine LiteratureDocument8 pagesPhilippine LiteratureisaiahPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Manila V Judge LaguioDocument6 pagesCity of Manila V Judge LaguioJay CezarPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest Pubcorp3Document12 pagesCase Digest Pubcorp3Myles Laboria100% (1)

- Laguna Lake Development Authority v. Court of Appeals and OthersDocument6 pagesLaguna Lake Development Authority v. Court of Appeals and OthersRushid jay SanconPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On Police PowerDocument7 pagesNotes On Police Powerapril arantePas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 2 CasesDocument15 pagesConsti 2 CasesCarlos DauzPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 15 To 18Document12 pagesConsti 15 To 18Jelaine JimenezPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Manila v. Laguio DigestDocument5 pagesCity of Manila v. Laguio DigestKarmille BuenacosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 2 Police PowerDocument32 pagesConsti 2 Police PowerBrent TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Law 2 Case DigestsDocument14 pagesConstitutional Law 2 Case DigestsMirafelPas encore d'évaluation

- Rutter Vs Esteban G.R. NO. L-3708. MAY 18, 1953)Document5 pagesRutter Vs Esteban G.R. NO. L-3708. MAY 18, 1953)abethzkyyyyPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Law 2 Case DigestsDocument15 pagesConstitutional Law 2 Case DigestsRed Hood100% (2)

- 6 - 10 Inherent LimitationsDocument3 pages6 - 10 Inherent LimitationsLAW10101Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ermita-Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Association, Inc. vs. City Mayor of Manila 20 SCRA 849 FactsDocument80 pagesErmita-Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Association, Inc. vs. City Mayor of Manila 20 SCRA 849 FactsLaila Ismael SalisaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ermita-Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Association, Inc. vs. City Mayor of Manila 20 SCRA 849 FactsDocument80 pagesErmita-Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Association, Inc. vs. City Mayor of Manila 20 SCRA 849 FactsLaila Ismael SalisaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ermita-Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Association, Inc. vs. City Mayor of Manila 20 SCRA 849 FactsDocument80 pagesErmita-Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Association, Inc. vs. City Mayor of Manila 20 SCRA 849 FactsLaila Ismael SalisaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pascual v. Secretary of Public Works: Legal StandingDocument7 pagesPascual v. Secretary of Public Works: Legal StandingAvarie BayubayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Exemptions To Be Considered, and No More. Since The Law States That, To Be Tax Exempt, EquipmentDocument7 pagesThe Exemptions To Be Considered, and No More. Since The Law States That, To Be Tax Exempt, EquipmentNorman jOyePas encore d'évaluation

- 261 280Document10 pages261 280Gabriel ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Art 13-18Document47 pagesArt 13-18Monika LangngagPas encore d'évaluation

- ConstiLaw 1Document21 pagesConstiLaw 1Ninotchka AbabaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 2 Case Digests RevisedDocument269 pagesConsti 2 Case Digests RevisedRecon DiverPas encore d'évaluation

- Equal Protection of The LawsDocument16 pagesEqual Protection of The LawsGlyza Kaye Zorilla PatiagPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 181293 - Topic - Power of The President - The Control PowerDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 181293 - Topic - Power of The President - The Control PowerGwendelyn Peñamayor-MercadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax Case Digests (Constitutional Limitations)Document5 pagesTax Case Digests (Constitutional Limitations)Meet MeatPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 2 CasesDocument75 pagesConsti 2 CasesYen055Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pasei V. DrilonDocument25 pagesPasei V. DrilonLyka Dennese SalazarPas encore d'évaluation

- Contract Clause (Case Digest)Document3 pagesContract Clause (Case Digest)Chris InocencioPas encore d'évaluation

- Case ConstiDocument9 pagesCase ConstiJincy Biason MonasterialPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 660 Art III CollatedDocument487 pages1 660 Art III CollatedGabriel ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- CONSTI Case DigestsDocument79 pagesCONSTI Case DigestsMegan Nate100% (3)

- Public Corporation Case DigestDocument139 pagesPublic Corporation Case DigesteipangilinanPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti2 Case DigestsDocument17 pagesConsti2 Case DigestsMyco MemoPas encore d'évaluation

- Solicitor General V Metropolitan Manila AuthorityDocument10 pagesSolicitor General V Metropolitan Manila AuthorityDon So HiongPas encore d'évaluation

- A. Police Power Until Non Impairment ClauseDocument84 pagesA. Police Power Until Non Impairment ClauseTogz MapePas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 2 Digests (Finals) (Final Edit)Document124 pagesConsti 2 Digests (Finals) (Final Edit)Jotham FunclaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest On Police PowerDocument10 pagesCase Digest On Police PowerKatrina Anne Layson YeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Basco vs. PAGCOR (G.R. No. 91649) - DigestDocument51 pagesBasco vs. PAGCOR (G.R. No. 91649) - DigestChristle PMDPas encore d'évaluation

- Police PowerDocument6 pagesPolice Powerkailamarie.ekabusyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Digest White Light Vs City of ManilaDocument2 pagesDigest White Light Vs City of ManilaCherry BepitelPas encore d'évaluation

- Basco vs. PAGCOR (G.R. No. 91649) - Digest FactsDocument18 pagesBasco vs. PAGCOR (G.R. No. 91649) - Digest FactsApril CelestinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Carlos Superdrug vs. DSWDDocument2 pagesCarlos Superdrug vs. DSWDAnge DinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Progressive Vs QC: Basco V PagcorDocument5 pagesProgressive Vs QC: Basco V PagcorJoshuaLavegaAbrinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Demolition Agenda: How Trump Tried to Dismantle American Government, and What Biden Needs to Do to Save ItD'EverandDemolition Agenda: How Trump Tried to Dismantle American Government, and What Biden Needs to Do to Save ItPas encore d'évaluation

- Fire & Smoke: Government, Lawsuits, and the Rule of LawD'EverandFire & Smoke: Government, Lawsuits, and the Rule of LawPas encore d'évaluation

- Questions 3 and 4 JurisprudenceDocument1 pageQuestions 3 and 4 JurisprudenceimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs Henry Go - Private IndividualDocument3 pagesPeople Vs Henry Go - Private IndividualimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Brief TemplateDocument1 pageProject Brief TemplateimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Solidum vs. People, 718 SCRA 263Document2 pagesSolidum vs. People, 718 SCRA 263imXinY100% (1)

- Frivaldo Vs Comelec Frivaldo Vs COMELEC (174 SCRA 245)Document7 pagesFrivaldo Vs Comelec Frivaldo Vs COMELEC (174 SCRA 245)imXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs SoriaDocument3 pagesPeople Vs SoriaimXinY100% (2)

- People Vs JanjalaniDocument3 pagesPeople Vs JanjalaniimXinY100% (1)

- Jimenez Vs SorongonDocument2 pagesJimenez Vs SorongonimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Uy Vs Javellana 680 SCRA 13Document1 pageUy Vs Javellana 680 SCRA 13imXinY100% (2)

- Enrile vs. People, 766 SCRA 1Document3 pagesEnrile vs. People, 766 SCRA 1imXinY100% (1)

- #50 People Vs Estomaca (Arraignment and Plea)Document2 pages#50 People Vs Estomaca (Arraignment and Plea)imXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Asistio V PeopleDocument1 pageAsistio V PeopleimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Fenequito vs. Vergara, Jr. 677 SCRA 113Document2 pagesFenequito vs. Vergara, Jr. 677 SCRA 113imXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Ramiscal Vs Sandiganbayan FinalDocument3 pagesRamiscal Vs Sandiganbayan FinalimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Case No. 35 Antiquera V PeopleDocument1 pageCase No. 35 Antiquera V PeopleimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- People v. SandiganbayanDocument3 pagesPeople v. SandiganbayanimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- 46 People v. LaraDocument2 pages46 People v. LaraimXinY100% (1)

- Burgundy Vs ReyesDocument2 pagesBurgundy Vs ReyesimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Miguel v. SandiganbayanDocument2 pagesMiguel v. SandiganbayanimXinY100% (2)

- People v. Dumlao DigestDocument1 pagePeople v. Dumlao DigestimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Solgen CommentDocument97 pagesSolgen CommentimXinY100% (1)

- Lim V Kuo Co PingDocument2 pagesLim V Kuo Co PingimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Disini, Jr. vs. Secretary of Justice, 716 SCRA 237, February 18, 2014Document2 pagesDisini, Jr. vs. Secretary of Justice, 716 SCRA 237, February 18, 2014imXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Data Requirements For The TrainingDocument1 pageData Requirements For The TrainingimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Lacson V Executive SecretaryDocument2 pagesLacson V Executive SecretaryimXinY100% (1)

- Comerciante vs. PeopleDocument3 pagesComerciante vs. PeopleimXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- Case List 021117Document1 pageCase List 021117imXinYPas encore d'évaluation

- C C E (N) : ASH AND ASH Quivalents OtesDocument13 pagesC C E (N) : ASH AND ASH Quivalents OtesJoan LaroyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3 MCQDocument4 pagesChapter 3 MCQLương Vân Trang50% (2)

- Banking and Financial Services Law: University of Nairobi Faculty of LawDocument42 pagesBanking and Financial Services Law: University of Nairobi Faculty of Lawterryrotich86% (7)

- Screenshot 2023-02-21 at 1.23.27 AMDocument12 pagesScreenshot 2023-02-21 at 1.23.27 AMGracy AroraPas encore d'évaluation

- RCBC Vs de Castro (ProvRem)Document4 pagesRCBC Vs de Castro (ProvRem)Mich DonairePas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Services - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument5 pagesFinancial Services - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaKumar PritamPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Financial Management Regulations 2018Document50 pagesPublic Financial Management Regulations 2018mansaraymusa788Pas encore d'évaluation

- STC-NMB BANK - May 2020 PDFDocument13 pagesSTC-NMB BANK - May 2020 PDFaashish koiralaPas encore d'évaluation

- Harmonising Border Procedures - Position PaperDocument10 pagesHarmonising Border Procedures - Position PaperPeter SsempebwaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pardon Application GuideDocument9 pagesPardon Application GuideCBCPolitics100% (1)

- Precautions in Case of Special CustomersDocument6 pagesPrecautions in Case of Special CustomersPoke clips100% (2)

- As Man Engine PartsDocument2 pagesAs Man Engine PartsRAVEENDRA OFFICEPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Source DocumentsDocument10 pagesTypes of Source DocumentsNippun Abhi Attrey90% (10)

- Ist Year Cash Book & BRS, RevenueDocument4 pagesIst Year Cash Book & BRS, RevenueiramanwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Amir 12Document3 pagesAmir 12Dani KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- B.llaw Mcqs FinalDocument19 pagesB.llaw Mcqs FinalAtiq ChishtiPas encore d'évaluation

- Shaping The ICT Banking Inovations For The FutureDocument27 pagesShaping The ICT Banking Inovations For The FutureK T A Priam KasturiratnaPas encore d'évaluation

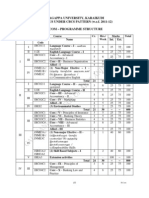

- Alagappa University, Karaikudi SYLLABUS UNDER CBCS PATTERN (W.e.f. 2011-12)Document26 pagesAlagappa University, Karaikudi SYLLABUS UNDER CBCS PATTERN (W.e.f. 2011-12)Mathan NaganPas encore d'évaluation

- Accounting RevisionDocument8 pagesAccounting RevisionAnish KanthetiPas encore d'évaluation

- e3eb6732-2d86-4a7f-9e34-eb3b58c8efdaDocument6 pagese3eb6732-2d86-4a7f-9e34-eb3b58c8efdaraj sahilPas encore d'évaluation

- National Law Institute University, Bhopal: Basics of E-BankingDocument21 pagesNational Law Institute University, Bhopal: Basics of E-BankingDikshaPas encore d'évaluation

- Https WWW - Cimb.bizchannel - Com.my Corp Front Transactioninquiry - Do Action Doprint PDFDocument1 pageHttps WWW - Cimb.bizchannel - Com.my Corp Front Transactioninquiry - Do Action Doprint PDFSyed HanafiePas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Notice of DishonorDocument4 pagesSample Notice of DishonorDon CorleonePas encore d'évaluation

- Applications LawDocument10 pagesApplications LawChasz CarandangPas encore d'évaluation

- Abridged Version of ProspectusDocument12 pagesAbridged Version of ProspectusAbbasi Hira100% (1)

- PDF RequiredDocument3 pagesPDF RequiredMANOJPas encore d'évaluation

- EMS 2010 November Question PaperDocument11 pagesEMS 2010 November Question PaperEstelle EsterhuizenPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Aspect of Banker Customer RelationshipDocument26 pagesLegal Aspect of Banker Customer RelationshipPranjal Srivastava100% (10)

- Job Advert - Asstant BMDocument4 pagesJob Advert - Asstant BMRashid BumarwaPas encore d'évaluation