Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Week 3 Caiata-Zufferey

Transféré par

coffeedanceCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Week 3 Caiata-Zufferey

Transféré par

coffeedanceDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

This article was downloaded by: [NUS National University of Singapore]

On: 03 November 2012, At: 19:35

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Health Communication

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hhth20

Physicians' Communicative Strategies in Interacting

With Internet-Informed Patients: Results From a

Qualitative Study

a

Maria Caiata-Zufferey & Peter J. Schulz

a

Department of Sociology, University of Geneva

Institute of Communication and Health, University of Lugano

Version of record first published: 19 Jan 2012.

To cite this article: Maria Caiata-Zufferey & Peter J. Schulz (2012): Physicians' Communicative Strategies in Interacting With

Internet-Informed Patients: Results From a Qualitative Study, Health Communication, 27:8, 738-749

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2011.636478

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic

reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to

anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents

will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should

be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims,

proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in

connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Health Communication, 27: 738749, 2012

Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 1041-0236 print / 1532-7027 online

DOI: 10.1080/10410236.2011.636478

Physicians Communicative Strategies in Interacting With

Internet-Informed Patients: Results From a Qualitative Study

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

Maria Caiata-Zufferey and Peter J. Schulz

Department of Sociology, University of Geneva

and Institute of Communication and Health, University of Lugano

This article describes the strategies used by physicians to interact with Internet-informed

patients, alongside illustrating the motives underlying such strategies. Semistructured interviews were conducted with a sample of 17 physicians from primary care and medical specialist

practices in the Italian part of Switzerland. The sample was diversified in terms of specialty,

age, and gender. Data collection and analysis were driven by grounded theory and supported

by a computer-assisted qualitative analysis program. A typology of four communicative strategies has been outlined. The adoption of these strategies is shaped by physicians general

attitude toward Internet-informed patients, based on their conception of medical information

for lay people through the Internet. However, this general attitude is mediated by doctors

interpretation of the specific communicative context, that is, their appraisal of three aspects:

the patients health literacy, the relevance of the online information to be discussed, and their

own communicative efficacy. At the end, the process of interpretation underlying the strategies

is discussed to expand on it and to identify implications for practice and research.

Nothing has recently changed clinical practice more fundamentally than a communication innovation: the Internet.

This statement reflects the position of a number of scholars and health practitioners concerning the impact of the

Internet on patients, doctors, and their relationship with one

another. In general, the Internet has been seen as having

remarkable potential for improving the physicianpatient

relationship by increasingly sharing the responsibility for

knowledge, by offering the possibility of more collaborative

models of physicianpatient interaction, and by fostering

greater patient involvement in health maintenance and care

(Wald, Dube, & Anthony, 2007). As a matter of fact, numerous studies have shown that the role of the Web in regard to

health care delivery and the physicianpatient relationship

is actually more complex than these positive expectations

suggest.

It is well established that patients increasingly use the

Internet for health information in all western societies (Fox,

2006; Spadaro, 2003). Despite its potential to challenge the

position of the health care provider, patients appear to see the

Correspondence should be addressed to Maria Caiata-Zufferey,

University of Lugano, Institute of Communication and Health, Via G. Buffi

13, 6900 Lugano, Switzerland. E-mail: caiatazm@usi.ch

Internet as an additional resource to support existing and valued relationships with their doctors (Caiata Zufferey et al.,

2010). Moreover, Internet-informed patients (IIPs) usually

report the improvement of their understanding and their ability to manage their health conditions (Akesson, Saveman,

& Nilsson, 2007). But if the lay public generally thinks

positively about health information on the Internet, physicians perceptions are more ambivalent. According to some

authors, health care professionals hold that the popularization of information alerts patients to important symptoms

at an earlier stage (Laing, Hogg, & Winkelman, 2004) and

helps them in the decision-making process (Giveon et al.,

2009). Consultations with IIPs can thus involve a more

patient-centered interaction (Wald, Dube, & Anthony, 2007).

Yet many studies also report negative reactions from physicians. Some doctors believe that Internet information can

generate patient misinformation, leading to distress, or an

inclination toward wrong self-diagnosis and/or detrimental

self-treatment (Ahmad et al., 2006). The consequence is an

increase in the number of patients questions and in requests

for inappropriate or unavailable testing or treatment, which

complicates the medical consultation (Dilliway & Maudsley,

2008) and adds a new interpretive role to the doctors clinical responsibilities (Sommerhalder et al., 2009). In addition,

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

PHYSICIANS COMMUNICATIVE STRATEGIES

several authors observed that providerpatient discussions

about Internet health information can be difficult, as the former may feel that patients will be unwilling to accept treatments offered to them or that patients are challenging their

authority (Ziebland et al., 2004). In her review article on

how patients online information-seeking behavior affects

their relationship with health providers, McMullan (2006)

synthesizes physicians reactions to IIPs by identifying

three outcomes: The health professional feels threatened by

patients bringing information into consultation, and reacts

defensively by asserting an expert opinion (professionalcentered relationship); the health professional and patient

work together to find and analyze the information (patientcentered relationship); the health professional guides

patients to reliable health websites (Internet prescription).

If attitudes and behaviors of physicians who are confronted with IIPs are ambivalent, understanding the motives

and the mechanisms underlying these attitudes and behaviors is crucial. Indeed, several studies indicate that physicians validation of patients efforts in health information

seeking on the Internet is essential to patient satisfaction and the reduction of worries (Bylund et al., 2007).

In addition, consultations can be disempowering if physicians refuse to discuss health-related Internet information

with patients (Sommerhalder et al., 2009). Therefore, the

question emerges of how to explain the differential responses

of physicians to IIPs.

A review of the literature provides some insight into

this issue. A first factor that influences the way doctors

respond to IIPs concerns physicians personal characteristics. On this point, Hardey (1999) considers that physicians

who are more accustomed to an authoritarian or paternal

role may have difficulty adjusting to a more collaborative role. Another important factor is the interrelatedness

between physicians and patients attitudes and behaviors.

The literature on doctorpatient interaction states that the

way doctors behave with patients strongly depends on the

way they perceive them and on the inferences they make

from various information cues. For example, Willems and

colleagues (2005) show that doctors are more likely to adopt

a participative style of communication with high-educated

patients than with low-educated patients. Concerning the

specific interaction between doctors and IIPs, Malone et al.

(2004) note that patients who use online information for

self-diagnosis and self-treatment (thus before the consultation) are likely to make doctors feel disempowered; on

the other hand, patients who search for online health information in order to better understand their diagnosis (thus

after the consultation) evoke a more positive attitude from

physicians.

These results show that investigating reciprocity and

mutual influence is a promising direction for the understanding of the interaction between doctors and IIPs. However,

although some hints are provided concerning physicians

differential responses to IIPs, the mechanisms underlying

739

these responses still need to be the focus of a systematic and

deep investigation (Ahmad et al., 2006).

This article reports the results of a qualitative study conducted among a heterogeneous group of Swiss Italian physicians, whose common characteristic was having ever treated

IIPs. The Italian part of Switzerland is a particularly interesting field for this study. The number of regular Internet

users has grown remarkably in recent years in Switzerland:

They were 60% in 2004 (Froidevaux & Tube, 2006) and

75% in 2010 (Froidevaux, 2011). Among Internet users, the

number of those who searched for health information on

the Web has grown from 20% (Froidevaux & Tube, 2006)

to 55% (Froidevaux, 2011) in the same period. The situation is slightly different in the Italian part of Switzerland;

in this region, only 64% of Swiss residents were found to

use the Internet regularly in 2010 (Froidevaux, 2011). While

no prior data exist, we can infer that the percentage was

even lower in the years before. The number of Internet users

for health information is not known, but we can conclude

that using the Internet for health information in the Italian

part of Switzerland is not yet an ordinary behavior, even

though it is certainly becoming more and more frequent.

Swiss Italians physicians are thus good informants of physicians responses to IIPs: The increasing frequency and the

novelty of patients information seeking on the Internet in

their region make them especially able to report what they

do and why.

From a more theoretical point of view, investigating

physicians communicative strategies with IIPs in the Italian

part of Switzerland allows exploration of medical interactions in a context of uncertainty. For Swiss Italian physicians, indeed, patients use of the Internet for health information is a relatively new pattern of behavior that could

undermine the professional monopoly of medical knowledge. When they face IIPs, these physicians have to ask

themselves what the expectations and the preferences of

these patients are. At the same time, they have to reconsider their role as information providers and more generally

as doctors. An increasing level of uncertainty then characterizes this kind of interaction, in the sense that subjects cannot

ascribe a predetermined meaning to a given behavior and

cannot anticipate the outcome of the interaction.

To explore how physicians manage IIPs, a set of sensitizing concepts was used (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The

concept of reflexivity of Anthony Giddens (1990) appeared

to be appropriate for this study. Reflexivity refers to the fact

that human beings constantly have to monitor their social

practices and to adapt them in the light of incoming information. Reflexivity has always formed an integral part of

the self and of the social relations. However, Giddens argues

that it becomes particularly pertinent in circumstances of

increasing uncertainty: When social practices are no longer

structured by established ways of doing things, the reflexive

monitoring of behavior becomes central and constant. This

study was also informed by the concept of good reasons

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

740 CAIATA-ZUFFEREY AND SCHULZ

of French sociologist Raymond Boudon. According to

Boudon (1989), peoples actions are determined by motives

that, despite not always being objectively rational, are

subjectively valid given the situation in which people are.

Subjectively good reasons are seen as valid because they are

founded on theories or conjectures that have been proven

valid in many cases. Therefore, subjectively good reasons

are not arbitrary, but tend to be general in the sense that

most individuals who are placed in the same situation will

tend to perceive the same reasons as good.

This conceptual framework is in line with the interpretative sociology of Max Weber (1968), which is focused on

understanding agency and motives of individuals. On the

basis of it, explaining the differential responses of physicians

to IIPs requires describing physicians actions (strategies)

in this situation and illustrating the good reasons behind

these actions. Illustrating the good reasons of physicians

strategies, then, requires, on one side, depiction of the theories, and, on the other side, highlighting the conjectures that

legitimate these strategies.

Consistently with this framework, three research questions oriented this study:

RQ1: What are the communicative strategies used by physicians when facing IIPs?

RQ2: What are physicians general representations (theories) behind their communicative strategies?

RQ3: What are physicians specific interpretations (conjectures) that influence, in turn, their communicative

strategies?

METHODS

This article forms part of a larger Swiss study that was

designed to explore the impact of popularization of health

information on the Internet on doctorpatient relationships. We adopted a qualitative methodology using a general grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

Approval for the whole study was obtained from the governing ethical committee, and informed consent was obtained

from each participant before data were collected.

Semistructured interviews were completed between

2006 and 2008 with a sample of physicians from primary

care and medical specialist practices. We decided to recruit

physicians in one city of the Italian part of Switzerland and

to exclude psychiatrists and paediatricians because of the

specificity of their relationship with their patients. Based on

these criteria, a prominent physician helped us to identify

a set of medical practices that would allow us to explore

physicians communicative strategies with IIPs. Sixty-nine

medical practices were identified, contacted first by letter

and then by telephone. Ten never answered. Twenty-eight

answered that they did not have time. Nine felt that they were

not able to participate because their caseload was old and not

used to the Internet; at our insistence, four of them agreed

to participate only in case we did not find enough participants, but then were unreachable when we tried to recontact

them some weeks later. Twenty-two agreed to participate

straightaway.

In line with the grounded theory approach, data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously until data

saturation was achieved. At the beginning, we interviewed

physicians chosen among those who were more willing to

participate. Then we selected physicians according to the

ongoing analysis: First, we tried to diversify the sample in

terms of physicians age; then, we tried to diversify the sample in terms of their specialty. This procedure allowed us to

maximize the variability of physicians experiences. At the

end, the sample size of 17 participants was judged large

enough to provide a variety of experiences and to allow

sufficient depth in the analysis. Participants were 3 women

and 14 men aged between 40 and 64 years (mean age 52).

They had between 15 and 39 years of practice (mean years

25). They were general practitioners (n = 5), gynecologists

(n = 3), orthopedic surgeons (n = 2), urologists (n = 2),

oncologists (n = 2), and one each were allergist (n = 1),

endocrinologist (n = 1), and rheumatologist (n = 1).

Interviews were conducted in physicians medical practices and lasted about 45 minutes. Participants were asked to

describe their experience with IIPs in the order and manner

desired. However, to make sure all the points were covered, we prepared a flexible interview grid with the main

topics to be treated. Sixteen interviews were recorded and

transcribed to improve data management and content examination. One physician refused to be recorded. In this case,

detailed notes were taken during and immediately after the

interview. The collected data did not allow for a systematic

and refined analysis, as was the case with the other interviews. However, they were used to test the emerging model

and to expand on it. The interview was thus included in the

final sample, even though the lack of verbatim transcription

precludes quotations from it in this article.

During the transcription process, participants personal

data were removed. Data analysis was inspired by the constant comparative method (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). A general inductive approach was used to code every interview, to

link and group the identified codes into larger categories, and

to define more abstract concepts. These operations, which

had to be creative and rigorous at the same time, allowed

for reduction and interpretation of the large amount of data

and were realized with the support of the software for qualitative analysis Atlas.ti (Muhr, 2004). Literature was used

throughout the process of analysis as a means of questioning

and interpreting the retrieved categories. For example, after

we noticed that physicians appraised several characteristics

of the patient in order to decide how to behave, the article

of Willems et al. (2005) helped us to interpret these data by

suggesting the importance of patients education and, finally,

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

PHYSICIANS COMMUNICATIVE STRATEGIES

by suggesting the category of patients health literacy. We

sought then evidence for this category by returning to the

data.

The results proposed in this article are the outcome of this

continual to-and-fro movement between empirical data and

developing theory, and provide a general model of physicians communicative strategies with IIPs. The first author

performed the interviews and the analysis. However, the

analysis was regularly discussed by both authors. Some quotations have been chosen from the qualitative data for their

illustrative power. They have been translated word-for-word

from Italian to English. When the extracts were not understandable with a literal translation, we preserved the cultural

meanings and nuances.

RESULTS

According to the participants, patients who search information on the Internet before their medical consultation are still

a minority, although their number has increased in recent

years. However, physicians recognize that probably some

IIPs do not explicitly say that they have been on the Internet

for fear of offending the physician.

When online information is brought to consultationon

the initiative of the patient or at the doctors invitation

doctors state that patients requests are threefold. Patients

may ask for clarification in order to better understand what

they have found. This request is usually followed by one

for contextualization: Patients may ask whether the retrieved

information can be applied to their case. Lastly, patients may

make suggestions on diagnosis and treatment, based on what

they found online.

For all the doctors, patients online information seeking constitutes a potential nuisance for their professional practice, as it disturbs the traditional course of

the consultation. Participants consider that the popularization of health information through the Internet has made

their role more complex, has broken routines and modified standard procedures. The following physician clearly

expresses this feeling, which was actually shared by all the

participants:

You are required to do more. More. You are required to

go beyond a known way of doing things, a usual way of

doing things. And this is not only due to the form of the

information or to the electronic tool. This has really to do

with the content of what you have to say. (endocrinologist,

man, 42)

The key word of the preceding excerpt is more:

Physicians have the feeling that they have to do more, in

terms of the content and of the form of their professional

practice, when they face IIPs. The analysis of the interviews

allows exploring what is behind the word more.

741

Managing the Internet-Informed Patient: A Fourfold

Typology of Communicative Strategies

We can identify four strategies doctors use to deal with IIPs.

These strategies are presented as Weberian ideal types, that

is, as conceptual abstractions from reality described in their

extreme pure form (Weber, 1968).

Resistance to online information. The purpose of

this strategy is to neutralize the IIP. The physicians

communication aims at avoiding the confrontation with

Internet-derived material the patient tries to enter into the

consultation.

Physicians use several techniques to reach this purpose.

Usually they start with ignoring the Internet-derived information offered by the patient, as far as this is possible.

Indeed, some patients do not explicitly say that they have

been on the Internet. Although the content of their speech

and the words they use suggest that this was the case, physicians pretend not to notice it. When doctors cannot avoid

acknowledging the patients information seeking behavior,

they tend to discredit the Internet in a strong and peremptory

way. No dialogue is encouraged on the topic:

When patients tell me, yes, but on the Internet . . . , I

always cut short: On the Web you find everything and its

opposite, so forget it all and listen to what Im saying, which

is the standard. (gynecologist, man, 63)

Another technique to resist consists in devaluing the

online information brought by the patient into the consultation: Physicians show that they knew the information

perfectly and that they have already considered it, even if

they have not discussed it with the patient.

As a last technique, physicians often enjoin IIPs to

choose between the doctor and the Internet. Basically, the

message sent is that going on the Internet was not a good

idea at all, as this 60-year-old surgeon expresses it:

Patients who begin to talk about the Internet, I dont make a

long speech. I mean, if I see that they think they know more

than me, I let them understand that they can go and be treated

by Mister Web. (surgeon, man, 60)

Repairing online information. The purpose of this

strategy is to correct IIPs and relate to them the point of view

of the doctor. The communication process is thus characterized by the transmission of selected medical information

chosen by the doctor according to their representation of

what the patient should know.

Usually physicians start with identifying IIPs, if these do

not mention that they have been on the Internet. For example,

this gynecologist says that he is able to identify IIPs based

on the terms used during the consultation:

Sometimes patients tell me; some others I gather it from

the way they speak. In the sense that sometimes they come

out saying Ah, but dysplasia and I think that they do

not even know if this is ham or cheese! And thus I say:

742 CAIATA-ZUFFEREY AND SCHULZ

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

Excuse me, but where did you read that? And then I have

it. (gynecologist, man, 52)

Once the IIP has been identified, the repairing strategy

requires that the physician warns the patient and argues the

limits of the Internet. Attempts at persuasion take place and

several arguments are used: The quality of online information is bad, patients do not have enough experience to

identify relevant information, etc.

Physicians continue with evaluating the information

brought up by the IIP according to what they think the

patient should know. It is possible that the physician takes

time to understand the information brought to the consultation and suggests discussing it in a further consultation.

Regardless, when the discussion takes place, the physician

determines the value of the information. Once the doctor has

appraised it, the communication process is understood to be

a one-way flow: The doctor clarifies and contextualizes the

information following evidence-based criteria, and usually

no place is left for a dialogue around it. Doctors consider

this process of evaluation a necessary work in order to set

the record straight:

For us, the doctors, the problem is that before starting you

have to destroy. Patients come already with their theory and

you have to dismantle it. It takes some care, and then you

need to start anew. (allergist, man, 52)

Doctors who adopt the repairing strategy usually finish

by dissuading the patient from turning to the Internet again.

The dissuasion is often an implicit message of the warning process, but sometimes physicians also suggest explicitly abandoning the Internet information-seeking behavior.

Basically, the ultimate message is that going online to find

health information is not a good idea, but as it was done, it

is now necessary to make good on this mistake.

Coconstruction around online information. The purpose of this strategy is to build a shared reality with the

patient using the online information brought to the consultation as a springboard for the discussion. Doctors aim to

create a consensus concerning the diagnosis and the treatment, and they use the online information as a starting point

to understand the patients point of view and to explain their

own.

As in the reparation strategy, physicians who adopt

coconstruction often start with identifying the IIP. Different

from the repairing strategy, however, a dialogue is conducted

once the discussion takes place. The communication process is understood to be a two-way flow: Physicians ask IIPs

questions in order to understand their motivations for searching for information, their views on their situation, eventually

their fears and preferences concerning the treatment; at the

same time, they clearly propose their own evaluation of the

information, based on their scientific knowledge but also

taking into account the point of view of the patient. Risks

implied in relying on the Internet are not stressed, as the

online information is not the main focus of the discussion

but only the starting point to build a shared reality. A patientcentered evaluation of the online information brought to the

consultation is thus realized. On this point, a male urologist

stresses the importance of working together to decide a

diagnosis and a therapy:

I simply say: Explain to me your problem. I try to focus

on their problem. Then we examine, we evaluate, we reject

hypotheses and we make the diagnosis. . . . We do not

discuss the validity of the Internet. In the end, retrieved information is marginal. I try to give patients a hand, I try to better

understand them, we make the diagnosis together, and we

decide the therapy together. (urologist, man, 44)

Evidence-based medicine guidelines are used as an indispensable resource in order to evaluate the information.

However, doctors accept going beyond these guidelines in

order to integrate the patients perspective. As an illustration, another urologist justifies the importance of integrating

the patients perspective by claiming that each patient is

unique, while the doctor is not necessarily in possession of

the absolute truth:

We take care of patients, we do not treat prostates. Thus,

guidelines are suitable as they show a direction, but one must

be able to go beyond standard indications. Because, after all,

who needs guidelines? Those who are not good, those who

are not able to take responsibility for their patient. . . . I have

learnt to take responsibility for my patients. I do things, I

observe, I look, but I know that I am not the truth holder just

because I am the physician. Thats why I always take into

account the point of view of the patient. (urologist, man, 53)

Coconstructive doctors usually end by encouraging the

patient to come back with other information and to discuss

it. The message sent, thus, is that going on the Internet is a

good idea, as it is gives patients a chance for discussing their

health problem more deeply with the physician.

Enhancement of online information. The purpose of

this strategy is to empower IIPs, that is, to make them proactive and provide them with the instruments to obtain other

good quality information.

In this case also, physicians often start with identifying

IIPs. They tend then to ask them about their information

searching process, that is, about how they performed it and

what they found. In this way, they evaluate patients competences in searching for health information online, and they

explore what kind of information patients have found, and

what kind of information they still need or want in order to

have a clear picture of the situation.

Regarding the specific online information brought to the

consultation, physicians conduct a neutral evaluation of it:

They complete it by adding other details, they mention

costs and benefits of the therapies, and they clearly talk

about possible risks. This evaluation is supplied in a very

objective way, and is usually devoid of value judgments

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

PHYSICIANS COMMUNICATIVE STRATEGIES

743

or personal suggestions. This excerpt from a 60-year-old

surgeon provides a good example:

than curing, one has to discuss. Yet discussing is by far not

considered the most important part of the job of physicians:

When patients come in my medical practice, they often get

scared [laughing]. Maybe then they regret that they have

asked me . . . [laughing]. Even though it is simply a gall

bladder or an inguinal hernia, I explain to them everything, I

explain also that they can die. Yes, I prefer doing it that way.

(surgeon, man, 60)

That kind of patient puts you on the spot, because you always

have to justify yourself, and the discussion takes long time.

. . . You fail to do your job, you cannot stop explaining.

(general practitioner, woman, 46)

Physicians usually finish by suggesting new valuable

information sources and by instructing patients about how to

recognize high-quality websites. The message sent by doctors who adopt the enhancement strategy is therefore that

going on the Internet is an excellent idea, as long as one is

able to select high-quality information sources.

The Good Reasons Behind the Strategies: General

Representations

How can we explain the adoption of the strategies just

described? The analysis of the interviews shows that a first

factor to be taken into account is the doctors representation of the IIP in general. In other words, physicians are

strongly influenced by their idea of health information for

patients and, consequently, by their idea of the Internet as

a tool for health information. Based on these conceptions,

doctors can be categorized as having a primarily resistant,

repairing, coconstructive, or enhancing attitude.

There is a clear difference between resistant physicians

and the three other categories concerning the conception of

health information patients hold. Resistant physicians tend

to consider patients information harmful. They consider

that the role of the doctor is curing the patient, and that the

role of the patient is complying with the doctor in order to

recover as soon as possible. Information is not taken into

consideration, as the two partners are considered too different to communicate on medical questions. A 59-year-old

surgeon exemplifies this point of view:

Doctors and patients . . . speak two completely different languages. As if I said my motor car has 120 horsepower and

one thinks that in my car there are 120 horses riding! The

problem is that the patient does not understand the problem

of the motorcar; they have a different idea of horses. This is

why you need to put things in order. Computer, informatics,

I do not understand anything about that, and I do not debate

with experts. (surgeon, man, 59)

Information is seen as harmful because it prevents the

doctor and the patient from doing their real jobs, which are

curing people (the doctor) and being committed to recovering (the patient). Consistent with this conception of patients

information, the Internet, as any other media source, is

considered a danger to the patients health and to the doctor successfully doing his work. A 46-year-old participant,

for example, emphasizes that patients who are too wellinformed make physicians unable to do their job: More

In contrast to resistant physicians, doctors belonging to

the three other categories agree in considering information

a necessary and positive aspect of the patients health care

and the doctorpatient relationship. All suggest that it is

the patients right to be informed and that well-informed

patients will be more compliant and satisfied. However,

physicians differ with regard to who should inform the

patient.

Repairing physicians think that health information should

be delivered exclusively by health professionals in the context of the medical consultation. They think that the popularization of health information generates confusion and

misunderstanding. Information should thus be selectively

provided by doctors, based on their experience and on their

knowledge of the patient. The underlying conception of the

doctors and the patients roles implies that the former is to

cure patients and transmit to them some information to make

them understand what is happening; the latter is to try to

understand the medical intervention and to comply with it.

As a 57-year-old general practitioner says:

Information is not necessarily good for everybody. It can

generate useless worries, lead people to imagine wrong

diagnoses, lead people to imagine side effects, etc.

Therefore, information is okay, but only if it is a well-judged

information, if it is adjusted to single patients and to their

capacity to integrate it. This is why informing is a doctors

task: because the doctor knows their patients. (general

practitioner, man, 57)

As a consequence, repairing doctors consider the Internet

a risk that they have to defuse. This risk is all the more acute

because of the characteristics of the tool: The Internet is

considered easily accessible, yet greatly unreliable.

Coconstructing physicians do not discriminate against

primary sources of health information. On one side, they

conceive that their role is to build an agreement on the diagnosis and the treatment, taking into account both patients

point of view and objective biological facts. On the other

side, they define the patients role as participating in

healthcare, providing information, suggesting preferences,

and negotiating decisions. Thus, coconstructing physicians

consider any health information the patient can find as valuable, provided that this information is discussed with a

health professional in the context of the medical consultation. This point of view is observable in the next excerpt:

In my opinion, people have to be informed, people have to

know what they have to face. In my opinion, this is right.

However, it is not right to think that if one is informed,

744 CAIATA-ZUFFEREY AND SCHULZ

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

then they will be free to decide. This is not right, because

those who face a health problem, they are not free. It is up

to the doctor to propose a treatment, and to persuade them,

as well. Because one needs to be convinced. (gynecologist,

woman, 53)

This type of physician considers the Internet, as well

as any other source of health information, a powerful tool.

Certainly, the Internet can eventually involve some risk.

Starting from the online information, nonetheless, doctors

can better understand their patients, they can propose a

diagnosis and a treatment that takes into account patients

psychosocial characteristics, and they can obtain patients

trust and adherence. As this 44-year-old urologist says, then,

in the end the Internet constitutes an opportunity for the

doctor:

I see a lot of advantages for the doctor. I mean, the patients

have got information, they have seen with their own eyes,

they have dealt with the topic. Therefore it is possible to

talk . . . extensively. Because they are prepared, they already

know something, and then it is easier to explain and to

discuss. (urologist, man, 44)

Similar to coconstructive physicians, enhancing doctors

do not discriminate against primary sources of health information. They consider that any medium is a legitimate

provider of health information, as long as high quality is

guaranteed. Implicitly, these doctors consider that patients

have the responsibility for decisions in their health care,

and that they are able to make the best decision, provided

that they base their decision on high-quality information.

For example, this 44-year-old doctor argues that high-quality

information helps patients in recognizing symptoms:

I think it is a good thing for patients to have access to medical

information. . . . But this only applies to high-quality information. Because it makes people proactive. For instance, it

makes people aware of insidious health problems that are

often discovered too late. (urologist, man, 44)

In this conception, the Internet is considered an opportunity for the patient. However, the condition to exploit it at

its best is that patients acquire a high competence in searching and evaluating information. It is part of the doctors role,

then, to instruct the patient in properly using this medium.

The Good Reasons Behind the Strategies: Specific

Interpretations

The doctors general representation of the IIP as already

discussed is important to understand the adoption of

the communicative strategies. Resistant, repairing,

coconstructive, and enhancing doctors, indeed, differ

in their level of openness toward online health information

for patients: Resistant physicians are the least open, while

enhancing doctors are best disposed toward it. Based on

their level of openness, physicians tend to adopt different

behaviors.

However, the interviews show that things are more complicated than it might appear. When asked to describe specific examples of interactions with IIPs, it clearly appears

that participants vary their strategies between and within

consultations. The majority of the participants are thus

not bound to a particular position: Although they claim

a basic general attitude toward IIPs, their actual way of

managing them, in the end, depends. A 53-year-old urologist provides the best illustration of this phenomenon.

He describes his communicative strategies as being often

between reparation and coconstruction. Asked about this

apparent contradiction, he answers:

You need to do the right thing with the right person. With

some people you take the time to look at the information

together, to evaluate it together. But there are also situations

where you say no, I dont want to go into it. You have to

consider, evaluate and grade, you need to weed some things

out and to keep others. (urologist, man, 53)

A closer examination of the physicians accounts shows

that the level of openness toward health information held by

patients can be increased or decreased based on a second

factor, that is, the physicians interpretation of the specific

communicative context with the IIP. In particular, doctors

act relying on their assessment of three aspects: the patients

health literacy, the relevance of the online information, and

their own communicative efficacy.

Patients health literacy. A perceived low level of

patients health literacy encourages physicians to adopt

a closed-minded position toward Internet information,

whereas a perceived high level pushes them to be more welldisposed. Health literacy is usually judged on the basis of

the patients cognitive and social skills. Regarding cognitive

skills, a highly educated patient is considered better able to

manage health information than someone with only a basic

education. Nonetheless, sometimes physicians are open to

IIPs with a lower level of education if these can count on the

assistance of highly educated family members. Additionally,

patients cognitive skills are evaluated also based on the

quality of the information brought into the consultation.

A 42-year-old physician emphasizes this point:

On electronic media, patients find information that is quite

crazy, and it puts me off beginning to have a closer look at it.

Yes, I say, My goodness, from where do we begin? Dont

you want to listen to me and thats enough? (endocrinologist, man, 42)

As for social skills, they refer to the patients ability to

behave properly with the doctor, that is, to respect the roles

by recognizing the doctors expertise and by remaining open

to their suggestions and remarks. If doctors think that IIPs

behave properly, it is likely that they will treat them with

PHYSICIANS COMMUNICATIVE STRATEGIES

more benevolence than someone with a self-important attitude. A 53-year-old urologist provides a clear example of

this:

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

A few times, when I was really exasperated, I have said:

Time is up! Those people were arrogant, and I have said

Time is up! Two of them then left really pissed, but after

the third repetition of the same thing . . . Some patients do

not want to understand: They have their idea and they want

me to agree with it. (urologist, man, 53)

Relevance of the online information to be discussed.

A perceived low level of relevance encourages physicians to

adopt a closed-minded position toward the Internet-retrieved

information held by a patient, whereas a high level pushes

them to be more well-disposed. Relevance is primarily

defined in terms of its direct influence on the patients health

and general well-being. Usually, the information is considered relevant if it refers to rare or chronic diseases. In these

cases the information-seeking behavior is considered perfectly legitimate, as it helps patients to better understand

their health problem and to manage it in their daily life.

The physicians position toward information seeking in

case of serious disease is more ambiguous. Some doctors

think that in case of serious disease the patient has neither the

skills nor the tranquility to search and evaluate health information on the Internet. In contrast, other physicians consider

it perfectly legitimate that patients search for health information in the case of life-threatening diseases, because of the

issues involved in their situation. Some physicians also evaluate the relevance of the information based on the interest

the patient shows toward it and on their preferences.

Physicians communicative efficacy. When they

have to decide how to respond to IIPs, physicians also estimate their own capacity or possibility of discussing the

online information in a satisfactory way. If they estimate that

their communicative efficacy in a specific situation is low,

physicians tend to adopt a closed-minded position toward

IIPs. On the other hand, if they think that the level of

their communicative efficacy is high, they tend to be more

well-disposed.

Physicians primarily assess their communicative efficacy

on the basis of their medical knowledge around the information brought into the consultation. The next account is particularly illustrative on this point. The participant explains

that he tends to adopt a resistant attitude with IIPs when he

feels uncertain on the topic to be discussed.

The problem is that today it is not easy to make things

understandable, because often even us, the doctors, we do

not understand what we are saying. . . . I give an example:

breastfeeding and allergy. I have heard everything and its

opposite: Avoid everything, otherwise the baby will become

allergic; eat everything to diminish intolerance; eat everything, except this and this. Every three years there is a new

theory. . . . A woman comes and tells me that she has heard

this and that. As a doctor, I tell her the current theory and

745

meanwhile I think: What a fib am I telling? In three years,

this will be worthless. . . . This is our problem: we are

not sure anymore. We, the doctors, we are more and more

unsure, and we are not able to give good reasons. You can

imagine that I didnt feel very comfortable with this woman.

(allergist, man, 52)

Sometimes, it also happens that physicians evaluate their

communicative efficacy based on the time they have for discussing with patients. On this point, the experience of this

57-year-old GP is illustrative:

It depends how the day is going on, too: A few days ago,

there was a medical emergency and afterward the waiting

room was crowded. A patient came with some printed sheets

and I passed him by in a flash. Of course, I am not proud of it,

but one has to come to terms with the reality. And to discuss

takes time. (general practitioner, man, 57)

To summarize, doctors communicative strategies are

influenced by their appraisal of the communicative context

in which they are involved. As three aspects are taken into

consideration, the chosen communicative strategy is usually

a kind of compromise. The following physician is clear

about this point:

You know, apparently physicians behave having in their head

an idea of what the doctorpatient relationship should be, but

actually I can assure you that for every act I commit, I have a

lot of things in my head. Every act is ... how to say ... a reasonable compromise between several alternatives. (general

practitioner, man, 49)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this article, we have outlined a general model of the

strategies used by physicians in interacting with IIPs, starting from the point of view of the physicians themselves.

In general, the analysis confirms that patients online information seeking is not yet the norm in the Italian part of

Switzerland. According to the participants, only a minority

of patients searched for health information in the Internet

prior to their appointment. This perception may be explained

by the fact that the number of IIPs is still moderate in this

region (Froidevaux, 2011). It is also possible that IIPs did

not tell the doctor that they had surfed the Internet, as this

behavior may be seen as improper. This is all the more likely,

as physicians still represent the most legitimate source of

information for health topics among the Swiss population

(Seematter-Bagnoud & Santos-Eggimann, 2007). Thus, it

is no accident that the interviewed physicians consider the

course of the medical consultation as being disturbed by

patients who introduce the Internet in it.

In this context, four physicians responses to IIPs emerge:

resistance, repairing, coconstruction, and enhancement. The

former two can be considered physician-centered strategies, the latter two patient-centered strategies. Physicians

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

746 CAIATA-ZUFFEREY AND SCHULZ

opt for a particular communicative strategy on the basis

of their conception of the medical information available to lay people on the Internet. This general attitude toward IIPs is then mediated by physicians interpretation of the specific communicative context, that is,

their appraisal of the patients health literacy, the relevance of the online information to be discussed, and their

own communicative efficacy. These results are summarized in Table 1. Based on these considerations, we can

argue that physicians communicative strategies are partly

personality-dependent, that is, resulting from a stable

system of beliefs, and partly context-dependent, that is,

depending on circumstances, time and place, thus subject to

vary across situations.

The variety of physicians responses to IIPs is consistent with the consulted literature. Several studies have

observed the same diversity in physicians attitudes toward

IIPs. The Internet has been found to be seen both as a

source of opportunity and a source of trouble (Ahmad

et al., 2006; Sommerhalder et al., 2009). Similar to our

study, furthermore, the literature shows that physicians

may react to IIPs in different ways. For example, the

three responses identified by McMullan (2006) can be

related to the four communicative strategies described

in this article (defensive reaction parallels resistance and reparation, collaborative reaction parallels

coconstruction, Internet prescription reaction parallels

enhancement).

If we consider how the Internet influences the doctor

patient relationships in general, we can see that it does not

necessarily shift consultations toward patient-centeredness,

as it could be expected (Wald, Dube, & Anthony, 2007).

With reference to Roters (2000) prototypes of doctor

patient relationship, we can assume that the physicians

strategies of resistance and repairing will generate a paternalistic relationship, provided that the patient accepts the

doctors dominance in agenda setting, goals, and decision

making. In contrast, a default relationship will develop if

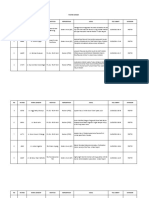

TABLE 1

Physicians Communicative Strategies in Interacting With Internet-Informed Patients

Resistance

Characteristics of the

communication

strategies

General

representations

behind the

strategies

Specific

interpretations

behind the

strategies

Repairing

Coconstruction

Enhancement

Purpose

Neutralize the

patient

Correct the patient

Build a shared reality

with the patient

Empower the patient

Techniques

Ignore the patient

Discredit the Internet

Devalue the online

information

Enjoin to avoid other

online information

Identify the patient

Argue the limits of the

Internet

Evaluate the online

information in a

physician-centered

way

Dissuade from

looking for other

online information

Identify the patient

Ask about motives of

online health

information

Evaluate the online

information in a

patient-centered

way

Encourage to come

back with other

online information

Identify the patient

Ask about modalities

and results of

online health

information

Evaluate the online

information

neutrally

Suggest new

high-quality online

information

Ultimate message

Its bad that you

were on the

Internet.

Its bad that you

were on the

Internet, but lets

consider what you

have found.

Its great that you

were on the

Internet. Lets

consider what you

have found.

Its great that you

were on the

Internet. Here are

some other good

websites.

Conception of health

information for

patients

Information is useless

or harmful

Information is fine

only if it comes

from the

consultation

Information is fine

only if it is brought

to the consultation

Information is fine

only if it is of good

quality

Conception of the

Internet as provider

of health information

Internet as a damage

Internet as a risk

Internet as an

opportunity for the

doctor

Internet as an

opportunity for the

patient

Patients health literacy

Low health literacy- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -High health literacy

Information relevance

Low relevance- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -High relevance

Physicians

communicative

efficacy

Low efficacy- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - High efficacy

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

PHYSICIANS COMMUNICATIVE STRATEGIES

the patient contests it. Coconstruction is likely to produce

mutuality, that is, the doctor and the patient are both experts

in their fieldsmedical discipline for the doctor; values,

needs, and experience of the body for the patientand

become partners in negotiating goals, agenda, and decisions.

Yet the relationship may come to a kind of default if the

patient refuses to go along with the physicians expectations.

Lastly, enhancement will generate a consumerist relationship if the patient accepts being an autonomous decision

maker, or a default relationship if the patient refuses to

assume this role. In brief, the Internet may affect the doctor

patient relationship differently, depending on physicians

responses and on patients expectations. The default relationship may be frequent, since it is not rare that physicians

and patients perspectives differ in terms of the way of treating the online information during the medical consultation

(Imes et al., 2008).

Beyond confirming the ambivalence of the Internet in

shaping the doctorpatient consultation, the main contribution of this study is the illustration of the mechanisms

underlying the physicians communicative strategies. In particular, this article highlights the process of interpretation of the communicative context that physicians perform during the medical consultation and that ultimately

informs their responses to IIPs. This finding is consistent

with the literature that claims the importance of interrelatedness of patients and physicians in the understanding

of the medical interaction (Ahmad et al., 2006; Bylund

et al., 2007; Malone et al., 2004; Willems et al., 2005).

However, our study goes beyond that, in the sense that it

describes how in fact physicians interpret the communicative

context.

The process of interpretation is necessary as the interaction with an IIP patient involves a dimension of uncertainty

for the physician: When confronted with IIPs, physicians

have to wonder about the patients capacity to understand,

the patients expectations and preferences in terms of information, and their own capacity to explain. Consultations

with IIPs, indeed, present some risks for the physicians,

such as the risks of misleading the patient, of displeasing the

patient by refusing to join a discussion of online information,

or of losing face. To manage these risks, physicians have to

increase their level of reflexivity, with reflexivity referring

to the constant revision of social activity in light of incoming information (Giddens, 1990). Physicians cannot simply,

as in the golden age of doctoring, serenely dispense

both medication and authoritative judgment (McKinlay &

Marceau, 2002); they are involved in a continuous process of

recognition of self and of other, that is, they have to reflect

actively on their own and others actions in order to make

sense of the best way to act and thus to orient their behaviors. Certainly this is valid for any medical consultation

these days, but it is particularly true for consultations including IIPs, because of the specific dimension of uncertainty

involved in them.

747

What is important to underline is that this process of

interpretation is complex, delicate, and crucial. First, it is

complex because physicians have to take into account three

different factors simultaneously: the patients health literacy, the relevance of the online information to be discussed,

and their own communicative efficacy. These three factors

might suggest contradictory paths of action. For instance, a

health-literate patient would encourage an enhancing strategy, but if this literate patient wants to discuss irrelevant

information in depth, this would rather suggest a resistant strategy. This shows that the process of interpretation

also requires a work of arbitrage in order to decide what

aspect to favor. Second, it is delicate because the risk of

mistakes is always present and cannot be ignored. Indeed,

as doctors adopt their communicative strategies based on

their appraisal of different aspects that might contradict one

another, the adopted strategy might be a compromise that

does not perfectly fit the patient. Additionally, the literature has shown that physicians inferences about patients

are often incorrect (Charles, Gafni, & Whelan, 1997). Third,

the process of interpretation is crucial because wrong inferences can create misunderstandings and decrease the quality

of health care (van Ryn et al., 2006) and, consequently,

impact patients health outcomes (Travaline, Ruchinskas, &

DAlonzo, 2005).

Beyond illustrating the interpretation process that underlies the way physicians adopt their communicative strategies

when facing IIPs, this study provides an example of reflexivity in action. This example confirms Giddenss idea (1990)

that reflexivity is a central issue in uncertain interactions, and

that it has a double-edged nature, meaning that it leads to

greater flexibility of action, but at the same time it requires a

continuous and demanding work to adjust ones behavior

to others. Despite the effort made to monitor their own conduct and that of others and to revise their social activities in

light of incoming information, however, no certainty exists

about the success of the behavioral adjustment and about the

outcome of the interaction.

These findings should be considered in light of the

studys limitations. Physicians strategies were explored

through semistructured interviews. This method was appropriate to understand the logic behind physicians behaviors,

but it did not allow examining the strategies in situ. Data

collected thus rely on physicians reconstruction. Besides,

the sample might be biased toward those doctors who were

willing to tell their experience. We also could not reach a

balance between men and women. Finally, because of the

limited number of the interviews, we could not examine the

role of specific variables, such as physicians age, familiarity

with the Internet, or specialty.

Despite these limitations, this study allows a better understanding of physicians behaviors with IIPs and of the

process by which these behaviors occur. Some practical

implications result from it. From the point of view of the

doctor, all the communicative strategies are legitimate ways

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

748 CAIATA-ZUFFEREY AND SCHULZ

of interacting with IIPs. However, coconstruction can be

considered the best approach, as the Internet is used in this

situation as a means of strengthening rather than weakening

the physicianpatient bond. Two main implications for the

encouragement of coconstruction emerge from this study,

one that is physician oriented and the other that is patient

oriented. First, it would be important to develop health

communication training programs for doctors that take into

account the characteristics of the process of interpretation.

For example, it could be useful to increase physicians

awareness of their communicative strategies and of the

motives underlying their strategies. It may also be important to encourage physicians to avoid implicit inferences,

because these could be erroneous. For example, it is possible that information considered irrelevant by the physician

is important for the patient. Finally, techniques could be

suggested to physicians to face IIPs when they feel unsure

about the online information. For example, the physician

could suggest a follow-up consultation, in order to have

time to examine the online information prior to discussing

it. Second, this study has also shown that patients attitudes and behaviors contribute to shaping the way physicians

think and communicate about the illness that patients suffer

from. Patients could therefore be sensitized to their power in

medical consultation. This could be achieved, for example,

through patients association, through flyers from medical insurances, or through specific educational programs.

Websites monitored by health professionals could furthermore be offered to patients in order to help them retrieve

high-quality health information to be discussed with their

physician.

This study also suggests directions for future investigations. First, a validation study of the process of interpretation

would be useful. In this work, we have identified three

factors that physicians consider simultaneously when they

decide how to manage IIPs. Focus groups with different

kinds of physicians could help to complete these factors

and to deepen our understanding of their role in the choice

of communicative strategies. Second, quantitative designs

could be utilized to investigate the variables associated with

the resistant, repairing, coconstructive, and enhancing strategies. For example, it would be worthwhile to examine the

effects of physicians age, familiarity with the Internet,

and specialty on their choice of communicative strategies.

Old age and low familiarity with the Internet are likely

to be correlated with physician-centered communicative

strategies (Hardey, 1999). The role of medical specialty,

however, seems to be more complex. Our hypothesis is

that the medical specialty may influence the feeling of

self-confidence that physicians have in their medical knowledge. In our study, indeed, physicians with clear expertise

(for example, surgeons) seemed to be more confident in

their communicative efficacy than primary care physicians,

who have to face a large variety of health problems without being a specialist in any of them. Furthermore, some

studies argue that the way patients and doctors communicate influences patients behavior, quality of life, understanding of medical information, and even health outcomes

(Travaline, Ruchinskas, & DAlonzo, 2005). Thus, it would

be important to examine the outcomes of the different communication strategies. Third, experimental studies could

be conducted to investigate the work of arbitrage that

physicians do when their interpretation suggests contradictory communicative strategies. A standardized patient

design, for example, could be implemented to manipulate

the patients health literacy, the information relevance, and

the physicians communicative efficacy, in order to determine which of them has the largest effect on physicians

choice of communication strategies. These are all studies

that could help understand what really happens between

physicians and IIPs, why this happens, and what its consequences are, and that could contribute to making these

interactions as efficacious as possible.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, F., Hudak, P. L., Bercovith, K., Hollenberg, E., & Levinson, W.

(2006). Are physicians ready for patients with Internet-based health

information? Journal of Medical Internet Research, 8, e22.

Akesson, K., Saveman, B. I., & Nilsson, G. (2007). Health care consumers

experiences of information communication technologya summary of

literature. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 76, 633645.

Boudon, R. (1989). Subjective rationality and the explanation of social

behavior. Rationality and Society, 1, 173196.

Bylund, C. L., Gueguen, J. A., Sabee, C. M., Imes, R. S., Li, Y., &

Sanford, A. A. (2007). Providerpatient dialogue about Internet health

information: An exploration of strategies to improve the providerpatient

relationship. Patient Education and Counseling, 66, 346352.

Caiata Zufferey, M., Abraham, A., Sommerhalder, K., & Schulz, P.

J. (2010). Online health information seeking in the context of the

medical consultation in Switzerland. Qualitative Health Research, 20,

10501061.

Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Whelan, T. (1997). Shared decision making in the

medical encounter: What does it mean? Social Science & Medicine, 44,

681692.

Dilliway, G., & Maudsley, G. (2008). Patients bringing information to

primary care consultations: A cross-sectional (questionnaire) study of

doctors and nurses views of its impact. Journal of Evaluation in

Clinical Practice, 14, 545547.

Fox, S. (2006). Online health search 2006. Washington, DC: Pew Internet

& American Life Project.

Froidevaux, Y. (2011). Internet dans les mnages en Suisse [Internet in

Swiss households]. Neuchtel: OFS.

Froidevaux, Y., & Tube, V. G. (2006). Utilisation dInternet dans les

mnages en Suisse. Rsultats de lenqute 2004 et indicateurs [Internet

use in Swiss households. Results of the 2004 survey and indicators].

Neuchtel: OFS.

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Giveon, S., Yaphe, J., Hekselman, I., Mahamid, S., & Hermoni, D. (2009).

The e-patient: A survey of Israeli primary care physicians responses

to patients use of online information during the consultation. Israel

Medical Association Journal, 11, 537541.

Hardey, M. (1999). Doctor in the house: The Internet as a source of lay

health knowledge and the challenge to expertise. Sociology of Health and

Illness, 21, 820835.

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 19:35 03 November 2012

PHYSICIANS COMMUNICATIVE STRATEGIES

Imes, R. S., Bylund, C. L., Sabee, C. M., Routsong, T. R., & Sanford, A. A.

(2008). Patients reasons for refraining from discussing Internet health

information with their healthcare providers. Health Communication, 23,

538547.

Laing, A., Hogg, G., & Winkelman, D. (2004). Healthcare and the information revolution: Re-configuring the healthcare service encounter. Health

Services Management Research, 17, 188199.

Malone, M., Harris, R., Hooker, R., Tucker, T., Tanna, N., & Honnor, S.

(2004). Health and the Internet-changing boundaries in primary care.

Family Practice, 21, 189191.

McKinlay, J. B., & Marceau, L. D. (2002). The end of the golden

age of doctoring. International Journal of Health Services, 32,

379416.

McMullan, M. (2006). Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: How this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient

Education and Counseling, 63, 2428.

Muhr, T. (2004). ATLAS.ti (Version 5) [Computer software]. Berlin,

Germany: Scientific Software Development.

Roter, D. (2000). The enduring and evolving nature of the patientphysician

relationship. Patient Education and Counseling, 39, 515.

Seematter-Bagnoud, L., & Santos-Eggimann, B. (2007). Sources and level

of information about health issues and preventive services among youngold persons in Switzerland. International Journal of Public Health, 52,

313316.

Sommerhalder, K., Abraham, A., Caiata Zufferey, M., Barth, J., & Abel, T.

(2009). Internet information and medical consultations: Experiences

749

from patients and physicians perspectives. Patient Education and

Counseling, 77, 266271.

Spadaro, R. (2003). European Union citizens and sources of information about health (Eurobarometer 58.0). Brussels: European Opinion

Research Group (EORG).

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded

theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Travaline, J. M., Ruchinskas, R., & DAlonzo, G. E. (2005). Patient

physician communication: Why and how. Journal of the American

Osteopath Association, 105, 1318.

van Ryn, M., Burgess, D., Malat, J., & Griffin, J. (2006). Physicians

perceptions of patients social and behavioral characteristics and race

disparities in treatment recommendations for men with coronary artery

disease. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 351357.

Wald, H. S., Dube, C. E., & Anthony, D. C. (2007). Untangling the Web

The impact of Internet use on health care and the physicianpatient

relationship. Patient Education and Counseling, 68, 218224.

Weber, M. (1968). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. New York: Bedminster Press.

Willems, S., De Maesschalck, S., Deveugele, M., Derese, A., & De

Maeseneer, J. (2005). Socio-economic status of the patient and doctor

patient communication: Does it make a difference? Patient Education

and Counseling, 56, 139146.

Ziebland, S., Chapple, A., Dumelow, C., Evans, J., Prinjha, S., &

Rozmovits, L. (2004). How the Internet affects patients experiences of

cancer: A qualitative study. British Medical Journal, 328, 564570.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Textbook Solution Ch8Document10 pagesTextbook Solution Ch8coffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Questions For DSCDocument62 pagesQuestions For DSCcoffeedance0% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Week 3 Health Communication - RuttenDocument4 pagesWeek 3 Health Communication - RuttencoffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- FIN3102 Fall14 Investments SyllabusDocument5 pagesFIN3102 Fall14 Investments SyllabuscoffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- DSC 1Document7 pagesDSC 1coffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Practice MCQ Set 1Document3 pagesPractice MCQ Set 1coffeedance100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- FIN3102 01 IntroductionDocument88 pagesFIN3102 01 IntroductioncoffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Fabozzi Chapter09Document21 pagesFabozzi Chapter09coffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Chapter 1: IntroductionDocument13 pagesChapter 1: IntroductioncoffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Fabozzi ETF SolutionsDocument10 pagesFabozzi ETF SolutionscoffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Corporate Finance Workshop 1Document24 pagesCorporate Finance Workshop 1coffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- CH 13 Ans 4 eDocument33 pagesCH 13 Ans 4 ecoffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Chapter 15 Questions V1Document6 pagesChapter 15 Questions V1coffeedancePas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Fabozzi ETF SolutionsDocument10 pagesFabozzi ETF SolutionscoffeedancePas encore d'évaluation