Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Thomas Arthur Brief (As-Filed 09.23.16)

Transféré par

Montgomery AdvertiserTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Thomas Arthur Brief (As-Filed 09.23.16)

Transféré par

Montgomery AdvertiserDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 1 of 73

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 2 of 73

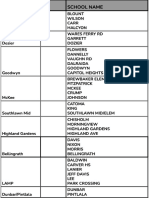

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

Under Fed. R. App. P. 26.1 and 11th Cir. R. 26.1-1, Mr. Arthur

certifies that the following is a complete list of all trial judges, attorneys, persons,

associations of persons, partnerships, or corporations that have an interest in the

outcome of this appeal:

Arthur, Thomas D

Roller, Justin D.

Brebner, Adam R.

Sherman, Meredith C.

Crenshaw, J. Clayton

Simpson, Lauren Ashley

Davenport, Carter

Stone, Sherrie

Dunn, Jefferson S.

Strange, Luther

Govan, Thomas R.

Toprani, Akash M.

Han, Suhana S.

Watkins, William Keith

Houts, James R.

Wicker, Judy (a.k.a. Mary

Turner)

Mar, Stephen S.

Wicker, Jr., Troy

-i-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 3 of 73

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Pursuant to 11th Cir. R. 28-1(c), Appellant Thomas D. Arthur,

through undersigned counsel, hereby respectfully requests that the Court hear oral

argument on this appeal. Oral argument will assist the Court in the disposition of

this action, which includes complex and novel issues of first impression

concerning the appropriate legal and evidentiary burdens placed upon a petitioner

challenging a lethal injection protocol.

-ii-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 4 of 73

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS .........................................................i

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT .............................................. ii

INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION.......................................................................... 4

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES............................................................................... 4

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS ............................................................................... 5

A.

Alabamas Lethal Injection Protocol .................................................... 5

B.

Alternative Methods of Execution ........................................................ 8

C.

ADOC Protocols Consciousness Assessment ..................................... 9

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................................................................. 9

A.

Mr. Arthurs Initial Complaint .............................................................. 9

B.

The States Change to Midazolam in its Protocol............................... 10

C.

Glossip and Mr. Arthurs Alternative Methods of Execution............. 13

D.

The Bifurcated Hearing ....................................................................... 14

E.

The First-Phase Opinion...................................................................... 15

F.

Mr. Arthurs As-Applied Claim .......................................................... 17

G.

Mr. Arthurs Motion for a New Trial .................................................. 18

H.

The District Courts Subsequent Opinions ......................................... 19

I.

Mr. Arthurs Execution Date ............................................................... 20

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ...................................................................... 21

STANDARDS OF REVIEW ................................................................................... 23

-iii-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 5 of 73

ARGUMENT ........................................................................................................... 26

I.

The District Court Misinterpreted the Requirement to Plead a Feasible

Alternative Method of Execution. ................................................................. 26

A.

The District Court Improperly Denied Mr. Arthur Leave to

Plead the Firing Squad as an Alternative Method of Execution. ........ 26

1.

Glossip Does Not Require Alternative Methods of

Execution To Be Permitted by Statute. ................................. 27

2.

Adopting the District Courts Interpretation of Glossip

Would Lead to Absurd Consequences. ..................................... 29

3.

B.

a.

The district courts ruling allows states to

legislatively exempt themselves from Eighth

Amendment review......................................................... 29

b.

The district courts holding will result in state-bystate variation in federal constitutional rights. ............... 31

Even if Glossip Does Require that an Alternative be

Permitted by Statute, Alabamas Death Penalty Statute

Authorizes the Firing Squad. .................................................... 32

The District Court Erred In Dismissing Mr. Arthurs Substantial

Evidence that Pentobarbital Is an Available Alternative to

Midazolam. .......................................................................................... 35

1.

The District Court Misconstrued the Burden Imposed by

Glossip by Effectively Requiring Mr. Arthur To Obtain

an Alternative Execution Drug. ................................................ 35

2.

The Burden Imposed by the District Court Conflicts with

Glossips Requirement that the State Undertake a GoodFaith Effort To Obtain an Alternative....................................... 40

3.

ADOCs Purported Attempts To Procure Pentobarbital

Were Inadequate. ...................................................................... 43

4.

The District Court Abused its Discretion by Prohibiting

Mr. Arthur from Obtaining Discovery To Show the

Availability of Drug Alternatives to ADOC. ............................ 45

-iv-

Case: 16-15549

II.

III.

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 6 of 73

The District Court Erred In Dismissing Mr. Arthurs As-Applied

Challenge Showing That Alabamas Lethal Injection Protocol Creates

a Substantial Risk that He Will Suffer a Painful Heart Attack. .................... 47

A.

The District Court Abused Its Discretion By Excluding Mr.

Arthurs Expert Evidence on Midazolams Hemodynamic

Effects. ................................................................................................. 49

B.

Even If Mr. Arthur Were Required To Plead and Prove an

Alternative for His As-Applied Claim, the District Court

Imposed An Unreasonable Burden of Proof. ...................................... 53

The District Court Erred In Dismissing Mr. Arthurs Equal Protection

Claim. ............................................................................................................. 55

CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................ 61

-v-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 7 of 73

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Page(s)

Cases

Ali v. Fed. Bureau of Prisons,

552 U.S. 214 (2008) ............................................................................................ 35

*Am. Textile Mfrs. Inst., Inc. v. Donovan,

452 U.S. 490 (1981) ..........................................................................36, 37, 39, 47

Arcia v. Fla. Secy of State,

772 F.3d 1335 (11th Cir. 2014) .......................................................................... 34

Arthur v. Allen,

452 F.3d 1234 (11th Cir. 2006) .......................................................................... 25

*Arthur v. Thomas,

674 F.3d 1257 (11th Cir. 2012) ..............................................................11, 24, 63

*Baze v. Rees,

553 U.S. 35 (2008) .......................................................................................passim

Boyd v. Myers,

No. 14-cv-1017, Dkt. # 50 (M.D. Ala. Oct. 7, 2015) ......................................... 34

Branca v. Sec. Ben. Life Ins. Co.,

789 F.2d 1511 (11th Cir. 1986) .......................................................................... 41

Brooks v. Warden,

810 F.3d 812 (11th Cir. 2016) ......................................................................37, 41

Buckler v. Israel,

2014 WL 6460112 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 25, 2014) .................................................... 48

Chavez v. Credit Nation Auto Sales, LLC,

641 Fed. Appx 883 (11th Cir. 2016) ................................................................. 43

City of Miami v. Wells Fargo & Co.,

801 F.3d 1258 (11th Cir. 2015) .......................................................................... 24

-vi-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 8 of 73

*Cooey v. Kasich,

801 F. Supp. 2d 623 (S.D. Ohio 2011) ............................................................... 58

Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharm., Inc.,

509 U. S. 579 (1993) .........................................................................20, 51, 53, 54

Ellison v. Nw. Engg Co.,

709 F.2d 681 (11th Cir. 1983) ............................................................................ 26

Gissendaner v. Commr, Georgia Dept of Corr.,

803 F.3d 565 (11th Cir. 2015) ............................................................................ 56

*Glossip v. Gross,

135 S. Ct. 2726 (2015) .................................................................................passim

Inv. Props. Intl, Ltd. v. IOS, Ltd.,

459 F.2d 705 (2d Cir. 1972) ............................................................................... 48

Martin v. Hunters Lessee,

14 U.S. (1 Wheat.) 304 (1816) ........................................................................... 33

Moore v. Balkcom,

716 F.2d 1511 (11th Cir. 1983) .......................................................................... 24

OKeefe v. Adelson,

2016 WL 4750213 (11th Cir. Sept. 13, 2016) .................................................... 47

*In re Ohio Execution Protocol Litig.,

671 F.3d 601 (6th Cir. 2012) .............................................................................. 58

Proudfoot Consulting Co. v. Gordon,

576 F.3d 1223 (11th Cir. 2009) .......................................................................... 25

Quiet Tech. DC-8, Inc. v. Hurel-Dubois UK Ltd.,

326 F.3d 1333 (11th Cir. 2003) ....................................................................26, 27

Quigg v. Thomas Cty. Sch. Dist.,

814 F.3d 1227 (11th Cir. 2016) .......................................................................... 26

Rosenfeld v. Oceania Cruises, Inc.,

654 F.3d 1190 (11th Cir. 2011) .......................................................................... 53

-vii-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 9 of 73

In re Rothstein, Rosenfeldt, Adler, P.A.,

717 F.3d 1205 (11th Cir. 2013) .......................................................................... 35

Seamon v. Remington Arms Co., LLC,

813 F.3d 983 (11th Cir. 2016) ............................................................................ 54

Smith v. Montana,

2015 WL 5827252 (Mont. Dist. Ct. Oct 6, 2015) ........................................31, 32

Smith v. United States,

133 S. Ct. 714 (2013) .......................................................................................... 42

Sprye v. Ace Motor Acceptance Corp.,

2015 WL 5136511 (D. Md. Aug. 31, 2015) ....................................................... 49

Toole v. Baxter Healthcare Corp.,

235 F.3d 1307 (11th Cir. 2000) .......................................................................... 25

Travelers Prop. Cas. Co. of Am. v. Moore,

763 F.3d 1265 (11th Cir. 2014) .......................................................................... 25

*United States v. Alabama Power Co.,

730 F.3d 1278 (11th Cir. 2013) ....................................................................26, 54

United States v. Jacques,

2011 WL 3881033 (D. Vt. Sept. 2, 2011) .......................................................... 33

*United States v. Johnson,

900 F. Supp. 2d 949 (N.D. Iowa 2012) .............................................................. 33

United States v. Jones,

125 F.3d 1418 (11th Cir. 1997) .......................................................................... 25

*United States v. One TRW, Model M14, 7.62 Caliber Rifle,

441 F.3d 416 (6th Cir. 2006) .............................................................................. 36

Warner v. Gross,

776 F.3d 721 (10th Cir. 2015) ............................................................................ 41

Wika Instrument I, LP v. Ashcroft, Inc.,

2014 WL 11970547 (N.D. Ga. June 3, 2014)..................................................... 48

-viii-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 10 of 73

Statutes

28 U.S.C. 1291 ........................................................................................................ 4

28 U.S.C. 1331 ........................................................................................................ 4

28 U.S.C. 1343(a)(3) ............................................................................................... 4

42 U.S.C. 1983 ...................................................................................................... 10

Ala. Code 15-18-82.1(c) .................................................................................34, 35

Colo. Rev. Stat. 18-1.3-1202 ................................................................................ 32

Miss. Code Ann. 99-19-51 .................................................................................... 32

Okla. Stat. tit. 22, 1014(A) .................................................................................... 29

Or. Rev. Stat. 137.473 ........................................................................................... 32

Other Authorities

29 Am. Jur. 2d Evidence 178 ................................................................................ 42

Websters Third New International Dictionary of the English Language (1976) ... 36

Websters Third New International Dictionary of the English Language (1981) ... 36

-ix-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 11 of 73

INTRODUCTION

Some methods of execution are unconstitutional; it follows that there

must be a way to prove it. In Glossip v. Gross, the U.S. Supreme Court set forth a

two-step roadmap for making that showing: first, a condemned prisoner must

show that the challenged method presents a substantial risk of severe pain, and

second, identify a known and available alternative method of execution that

entails a lesser risk of pain. 135 S. Ct. 2726, 2731 (2015).

In a little over a month, on November 3, 2016, the State of Alabama

intends to execute Thomas D. Arthur using a three-drug protocol that, as

established by expert evidence of record, bears a substantial risk of causing severe

pain and suffering.1 Mr. Arthurs constitutional challenge to this protocol using

midazolam as the first drug has been cut off without review of the merits of his

claim, however, by the district courts conclusion that Mr. Arthur cannot show the

availability of an alternative. The district courts rulingin effect, a nullification

of the Eighth Amendment rightwas in error. Mr. Arthur offered several feasible

alternatives to Alabamas protocolconstitutional alternatives actually used in

other statesincluding a firing squad or a single-drug protocol using pentobarbital.

In ruling that these alternatives were not feasible and readily implemented, the

1

On September 6, 2016, Judge Hull granted Mr. Arthur until October 4, 2016

to file his opening brief. In light of the execution order, Mr. Arthur has accelerated

his filing.

-1-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 12 of 73

district court misread Glossip, applied an impossibly stringent standard and

disregarded the evidence.

First, Mr. Arthur alleged that the firing squada method of execution

that is constitutionally acceptable and has been recently used in another stateis

available to Alabama as a practical matter, and is a more humane alternative to

Alabamas current execution protocol. The district court denied Mr. Arthur the

opportunity to plead this alternative, based on the unsupported legal conclusion

that the firing squad is not available, solely because it is not expressly prescribed

by Alabamas current execution statute. This is a profound misinterpretation of

Glossip. If condemned prisoners could plead only alternatives that are already

expressly permitted by statute, states could simply rule out all alternatives in their

execution laws and thus legislatively exempt any method of execution from Eighth

Amendment scrutiny. That is, in effect, the result of the district courts ruling here.

Second, despite being denied access to critical discovery, Mr. Arthur

amassed substantial evidence demonstrating the availability of an alternative drug,

pentobarbital, that could be used in an effective single-drug protocol that would not

present the substantial risks of Alabamas current protocol. Mr. Arthurs evidence,

including the unrebutted expert testimony of a doctor of pharmaceutical chemistry,

showed that several other neighboring states have in fact used Mr. Arthurs

proposed alternative in recent executions, and also that this alternative is available

-2-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

to Alabama through a variety of channels.

Page: 13 of 73

The district court misapplied the

standard and found that Mr. Arthur had not proven the drugs availability because

Mr. Arthur had not actually taken steps to procure the drug for Alabamawhich,

of course, he could not doand a lawyer for Alabamas department of corrections

testified that she was unable to obtain the drug through perfunctory telephone calls

to a number of Alabama pharmacies identified by Mr. Arthur.

Third, as a final alternative, Mr. Arthur identifiedat the district

courts directionmodifications to the implementation of Alabamas current

protocol using a drug in that protocol, which would alleviate at least some (but not

all) of the deficiencies of the current method, and address specific concerns arising

from Mr. Arthurs medical condition. This, too, was rejected by the district court

because Mr. Arthurs medical expert did not provide step-by-step execution

instructions, which he could not have done without violating ethical rules and his

oath as a physician.

The district courts holding renders it impossible for a

condemned inmate to propose an alternative based on medical evidence because no

medical expert could supply the detailed protocol that the district court demanded.

Additionally, the district court erroneously dismissed Mr. Arthurs

Equal Protection claim that Alabamas consciousness assessmentthe states

only purported safeguard against a torturous executionhas been inadequately

applied in previous executions. There was overwhelming evidence showing that

-3-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 14 of 73

execution team members did not know how to properly conduct the assessment

(because they were never instructed on how to do so).

The district court

disregarded this evidence by applying the wrong testthe district court analyzed

the claim through the Eighth Amendment, while this Court (and the district courts

own prior rulings) has clearly held that deviations from an execution protocol state

a Fourteenth Amendment claim.

*

Absent this Courts intervention, Mr. Arthur will soon be executed

without having been afforded the chance to prove that Alabamas method of

execution is highly likely to subject him to agonizing pain. The district courts

erroneous application of Glossip must be reversed.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The district court had jurisdiction over Mr. Arthurs action under 28

U.S.C. 1331 and 1343(a)(3), and dismissed Mr. Arthurs action on July 19,

2016.

Mr. Arthur timely appealed on August 18, 2016, and this Court has

jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. 1291.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1.

Whether the district court erred in its interpretation of Glossips

requirement that a method-of-execution challenger prove a feasible alternative by

(a) requiring that any alternative be expressly permitted by statute, and (b)

-4-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 15 of 73

imposing a requirement that Mr. Arthur must actually procure, or provide a

specific willing source, for drugs to be used in an alternative method of execution.

2.

Whether the district court erred in dismissing on summary

judgment Mr. Arthurs as-applied challenge on the basis that (a) Mr. Arthurs

medical expert had no experience administering lethal doses of drugs, and (b) Mr.

Arthurs medical expert did not provide an execution protocol because doing so

would have been a violation of ethical rules and his medical oath.

3.

Whether the district court erred in dismissing Mr. Arthurs

Equal Protection claim, challenging the States significant deviations from its

execution protocol, by analyzing Mr. Arthurs claim under the Eighth Amendment

instead of the Fourteenth, as this Court has instructed.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

A.

Alabamas Lethal Injection Protocol

To execute condemned prisoners, the Alabama Department of

Corrections (ADOC) currently uses a lethal injection protocol comprising the

injection of the following three drugs in order: (1) midazolam hydrochloride,

(2) rocuronium bromide, and (3) potassium chloride. R.E. Tab 2 at 3.2 It is

undisputed that the administration of the second and third drugs in the protocol

would cause agonizing pain and suffering if administered alone. The second drug

2

The record excerpts are cited as R.E. followed by the tab number and page

number within the document.

-5-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 16 of 73

in the protocol is a paralytic that stops muscle usage (but not the sensation of pain

or brain function), and so would effectively suffocate a conscious inmate in a

manner that has been compared to being buried alive. The third drug is a caustic

agent that produces a sensation akin to fire running through the veins. See Baze v.

Rees, 553 U.S. 35, 53 (2008); R.E. Tab 12 at 8-9. Accordingly, the only way to

avoid a torturous execution using these two drugs is to first use an anesthetic that

will render the condemned unconscious and insensate to pain.

Midazolamthe first drug in ADOCs lethal injection protocol, and

the only drug responsible for shielding an inmate from the second and third

drugsis not up to this task. Rather, midazolam is commonly used in clinical

settings to relieve anxiety and sedate patients before surgery; and although

midazolam is sometimes used for anesthesia in concert with one or (more

typically) several anesthetics, it isaccording to the FDA and the products own

packagingnot approved for use as a standalone general anesthetic. R.E. Tab 12

at 9-10.

There are well-accepted scientific reasons why midazolam is not used

as a general anesthetic for major surgery, and these reasons demonstrate equally

that it is not suitable for use in a constitutionally acceptable execution protocol.

Studies have shown that midazolam exhibits a ceiling effect, which means that

there is a level after which no additional dose of midazolam will have any impact.

-6-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 17 of 73

R.E. Tab 12 at 12. Critically, that ceiling for midazolam is below the level

necessary to induce a depth of anesthesia required for invasive surgeryor painful

executions. R.E. Tab 12 at 13-14. For example, practicing anesthesiologists

around the world utilize an FDA-approved device called a bispectral index (BIS)

monitor to measure an individuals depth of unconsciousness, using a scale ranging

from 0 (known as burst suppression or flatline EEG) to 100 (fully awake).

R.E. Tab 12 at 6-7. On this scale, midazolam has been shown to reliably result in a

depth of unconsciousness insufficient for use in a painful invasive procedure

requiring a general anesthetic. R.E. Tab 12 at 7.

Additionally, midazolam also has well-documented hemodynamic

effectsi.e., effects on the flow of blood within the body. R.E. Tab 10 at 5-7. In

particular, midazolam induces a sharp reduction in blood pressure immediately

upon injection; and for elderly individuals with coronary heart disease, the drop in

blood pressure that would accompany a large dose of midazolam is highly likely to

induce a heart attack. R.E. Tab 10 at 12-13. This drop in blood pressure happens

prior to any of the drugs sedative effects because the hemodynamic effects of

midazolam occur directly at the level of the vasculature (the blood vessels),

whereas midazolam must travel through the blood stream to reach the brain and

penetrate the blood-brain barrier before having any sedative effect. R.E. Tab 10 at

6.

-7-

Case: 16-15549

B.

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 18 of 73

Alternative Methods of Execution

Pentobarbital is part of a family of drugs called barbiturates, which

have been used to achieve deep anesthesia in decades of medical practice. R.E.

Tab 12 at 10-11. In contrast, midazolam is a benzodiazepine, part of the same drug

family as anti-anxiety medications Valium and Xanax. R.E. Tab 12 at 9. ADOC

has asserted that it changed its protocol from using pentobarbital to midazolam

because it could no longer acquire pentobarbital, even though (1) pharmacies

throughout Alabama are capable of compounding the drug (i.e., preparing the drug

for administration from its ingredients), (2) the active ingredient for pentobarbital

is available for sale in the United States or could be synthesized for the State, and

(3) four other states have used pentobarbital in executions in the past year alone.

R.E. Tab 2 at 10-14.

Additionally, other states have recently employed alternative forms of

capital punishment. For example, in 2010, Utah executed an inmate using the

firing squad, and experience with that form of execution has shown that if properly

implemented, it is both reliable and relatively painless. R.E. Tab 6 at 43-44.

Indeed, over the past century, a firing squad execution has never resulted in a

botched execution (i.e., resulting in an agonizing death for the inmate), in contrast

to more than 7% of lethal injection executions. R.E. Tab 6 at 44.

-8-

Case: 16-15549

C.

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 19 of 73

ADOC Protocols Consciousness Assessment

Under ADOCs lethal injection protocol, after the first drug is

administered, but before the last two drugs, ADOC personnel must perform a

consciousness assessment. R.E. Tab 50 at 10. The purpose of this assessment is

to ensure the inmate has been sufficiently anesthetized to withstand the pain of the

second and third drugs in the protocol.

R.E. Tab 2 at 22.

The assessment

prescribed by ADOCs protocol requires three steps:

R.E. Tab 50 at 10. If there is no response following this third step, ADOC

personnel will administer the second and third drugs of the protocol. R.E. Tab 50

at 10.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A.

Mr. Arthurs Initial Complaint

Thomas D. Arthur is a seventy-four year old inmate incarcerated at

Holman Correctional Facility (Holman), under sentence of death.

Mr. Arthur filed this action in the Middle District of Alabama on June

8, 2011, against ADOC, its commissioner, and the warden of Holman.3 Under 42

3

For convenience, this brief will hereafter refer to defendants collectively as

ADOC or the State.

-9-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 20 of 73

U.S.C. 1983, Mr. Arthur challenged the then-existing lethal injection protocol

ADOC intended to use for his execution. R.E. Tab 48. Mr. Arthur advanced

claims under the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and soon

afterwards, amended his complaint to include claims under the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the separation of

powers clause of the Alabama Constitution. R.E. Tab 47.

Soon after Mr. Arthur filed his action, ADOC moved to dismiss,

which the district court (Fuller, J.) granted on November 3, 2011. R.E. Tab 46.

The district court held that Mr. Arthurs Eighth Amendment claim was untimely,

and that his Fourteenth Amendment claim failed to state a claim. R.E. Tab 46. On

appeal, this Court reversed, holding that Mr. Arthurs Eighth and Fourteenth

Amendment claims could not be resolved without Mr. Arthur being afforded an

opportunity to conduct discovery and develop a factual record. Arthur v. Thomas,

674 F.3d 1257, 1261-63 (11th Cir. 2012).

B.

The States Change to Midazolam in its Protocol

Following remand, limited discovery took place concerning the

timeliness of Mr. Arthurs claims and the likelihood that ADOC would fail to

adequately conduct the consciousness assessment required by its protocol. After a

hearing on these two issues, ADOC moved for summary judgment, which the

-10-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 21 of 73

district court denied on September 30, 2013, finding genuinely disputed issues of

materials fact on both questions. R.E. Tab 27.

Thereafter, ADOC repeatedly sought and obtained adjournments of

further proceedings. See, e.g., R.E. Tab 40; R.E. Tab 39. But on September 11,

2014, the day before a scheduled status conference, ADOC filed a motion in the

Alabama Supreme Court to set a date for Mr. Arthurs execution. R.E. Tab 36. In

the motion, filed without any advance notice to Mr. Arthur or the district court,

ADOC disclosed for the first time that, the day before, it had changed its lethal

injection protocol to provide for the use of midazolam (a sedative) in place of

pentobarbital (an anesthetic) as the first lethal injection drug. R.E. Tab 36 at 2-3.

Concurrently with its filing of a motion to set an execution date, ADOC filed a

motion in the district court seeking dismissal of Mr. Arthurs Eighth Amendment

claim on the ground of mootness. R.E. Tab 37.

Shortly after the change to ADOCs protocol, Mr. Arthur moved for

leave to file a second amended complaint to challenge ADOCs new lethal

injection protocol. The district court (Watkins, J.)4 granted the motion, R.E. Tab

34, and denied ADOCs subsequent motion to dismiss, R.E. Tab 32.

On August 21, 2014, the action was reassigned from Judge Fuller to Judge

Watkins. R.E. Tab 38.

-11-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 22 of 73

The Second Amended Complaint alleged two constitutional

inadequacies in ADOCs protocol: First, Mr. Arthur alleged that midazolam was

not an appropriate anesthetic, both facially (because it is incapable of inducing

anesthesia prior to the administration of the other two agonizing drugs) and asapplied in Mr. Arthurs unique circumstances (because it would cause someone

with his particular health condition to suffer and feel an excruciating heart attack),

thereby violating Mr. Arthurs right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment

under the Eighth Amendment. Second, Mr. Arthur alleged that the States preexecution consciousness assessment has been inconsistently and inadequately

performed, violating Mr. Arthurs right to Equal Protection under the Fourteenth

Amendment. R.E. Tab 33.

The Second Amended Complaint also alleged two alternative methods

of execution: single-drug protocols using pentobarbital or sodium thiopental. Mr.

Arthur alleged that both of these drugs, administered gradually and in a sufficient

dose, were capable of inducing deep anesthesia and death without the substantial

risks of pain and suffering of Alabamas three-drug protocol.5

5

Although Mr. Arthur had challenged ADOCs prior protocol using

pentobarbital, that was in the context of a rapid bolus dose in a three-drug protocol:

Mr. Arthurs allegation was that pentobarbital would not adequately anesthetize

him in time for the administration of the second and third drugs and that the bolus

dose would induce a heart attack. The gradual administration of pentobarbital

without use of the second and third drugs would not implicate the risks identified

in Mr. Arthurs initial complaints.

-12-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 23 of 73

On December 23, 2014, while Mr. Arthurs motion to amend his

complaint was still pending, the Alabama Supreme Court granted ADOCs motion

to set an execution date, scheduling Mr. Arthurs execution for February 19, 2015.

R.E. Tab 35. On February 13, 2015, Mr. Arthur filed an emergency motion for a

stay of execution, R.E. Tab 59, which the district court granted, finding that Mr.

Arthur had met his burden of proving a likelihood of success on the merits of his

Equal Protection claim, R.E. Tab 31 at 12. This Court affirmed the stay, and no

appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was sought.

C.

Glossip and Mr. Arthurs Alternative Methods of Execution

On February 24, 2015, the State requested that Mr. Arthurs action be

stayed based on the U.S. Supreme Courts grant of certiorari in Glossip v. Gross,

which the State contended could change the legal framework for Mr. Arthurs

challenge. R.E. Tab 30. The district court granted the motion and stayed the case.

R.E. Tab 29. On June 29, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court released its opinion in

Glossip, which clarified that a method-of-execution challenger must plead and

prove a known and available alternative method of execution that is feasible,

readily implemented, and in fact significantly reduces a substantial risk of severe

pain. 135 S. Ct. at 2731, 2737 (internal quotation marks and alteration omitted).

Under the new Glossip framework, Mr. Arthur moved for leave to

amend his complaint to add further allegations concerning alternative methods of

-13-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 24 of 73

execution. R.E. Tab 28. The district granted the motion in part, allowing Mr.

Arthur to add additional allegations concerning his proposed alternative singledrug protocols, but denied Mr. Arthur leave to plead the firing squad as an

alternative, on the basis that Alabama law does not expressly permit the firing

squad as a method of execution. R.E. Tab 4.

Following Glossip, Mr. Arthur also sought discovery from ADOC on

its investigation and knowledge of available alternative methods of execution,

which the district court largely denied. R.E. Tab 27. Relevant to this appeal, the

district denied any discovery on: (1) the attempts or efforts by ADOC to obtain

any drugs for the purposes of lethal injection, including the identity of any

suppliers; (2) any alternative methods of execution identified or considered by

ADOC; and (3) ADOCs communications and knowledge concerning other states

uses of midazolam. R.E. Tab at 6-7.

D.

The Bifurcated Hearing

On October 8, 2015, the district court ordered a hearing on Mr.

Arthurs claims, to begin on January 12, 2016. Subsequently, Mr. Arthur and

ADOC finished document discovery, exchanged expert reports and completed

depositions.

On January 6, 2016, six days before the hearing, and after the parties

filed pre-trial briefs, exhibit lists and objections, deposition designations and

-14-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 25 of 73

objections, motions in limine, and briefs on an ADOC summary judgment motion,

the court orderedover Mr. Arthurs objectionthat the hearing would be limited

to two issues: (1) the availability of an alternative to ADOCs current lethal

injection protocol; and (2) Mr. Arthurs Equal Protection claim. R.E. Tab 23. Mr.

Arthur was thus barred in the first phase of the hearing from introducing evidence

on the significant harm that would be caused by ADOCs lethal injection protocol.

That is, only if Mr. Arthur prevailed on the first phase of the bifurcated hearing,

the district court ordered, would Mr. Arthur be permitted to show the substantial

risk of pain and suffering presented by the States three-drug protocol. R.E. Tab

23. The first phase of the bifurcated hearing, limited to the availability of an

alternative method and the Equal Protection claim, was held on January 12-13,

2016. See generally R.E. Tab 21; R.E. Tab 22.

E.

The First-Phase Opinion

On April 15, 2016, the district court released its opinion concerning

the issues litigated at the hearing (the First-Phase Opinion). R.E. Tab 2. The

court dismissed Mr. Arthurs facial Eighth Amendment claim on the basis that he

had failed to prove that the State could obtain the alternative drugs Mr. Arthur pled

in his complaint.6 R.E. Tab 2 at 19-21. Among other things, the district court

Citing Glossip, the district court stated that Arthur must prove by a

preponderance of the evidence an alternative method of execution that is feasible

-15-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 26 of 73

accepted Mr. Arthurs evidence that numerous pharmacies in Alabama could

compound pentobarbital, and that several other statesGeorgia, Missouri, Texas

and Virginiahad within the past year executed individuals using that drug, but

concluded that although pentobarbital may be available, that showing fell far

short of Arthurs burden. R.E. Tab 2 at 18, 20. The court also dismissed Mr.

Arthurs Equal Protection claim. R.E. Tab 2 at 52-54. The court stated that the

Eighth Amendment does not require a consciousness assessment, and therefore,

Mr. Arthur failed to state an Equal Protection claim challenging the adequacy of

this assessment. R.E. Tab 2 at 53. The court also rejected Mr. Arthurs evidence

showing that the consciousness assessment had not been performed in prior

executions.

Although the district court found the fact and expert testimony

presented by Mr. Arthur credible, and noted the existence of contemporaneous

records supporting Mr. Arthurs claims (ADOCs own execution logs), the court

held the testimony of ADOCs employees tasked with performing the

consciousness assessment overrode the evidence to the contrary. R.E. Tab 2 at 5152.

[and] readily implemented . . . or, in other words, is known and available. R.E.

Tab 2 at 9 (citation omitted).

-16-

Case: 16-15549

F.

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 27 of 73

Mr. Arthurs As-Applied Claim

Prior to issuance of the First-Phase Opinion, the district released an

order on February 24, 2016 stating that Mr. Arthur had failed to meet his burden to

show an available alternative and that an opinion addressing those issues would be

forthcoming (i.e., the subsequent First-Phase Opinion). R.E. Tab 20. The order

also stated that the court must now consider Arthurs idiosyncratic health

concerns relating to lethal injection, and directed both parties to propose a

modified protocol that reasonably addressed these issues. R.E. Tab 20 at 2. If the

parties failed to come to a stipulated solution, the district court ordered that the

parties file their respective proposals, supported by briefing and evidence, with

the court, and [i]f necessary, the court [would] conduct an evidentiary hearing.

R.E. Tab 20 at 3.

Following the district courts February 24 order, the parties exchanged

positions on modifications to ADOCs protocol. Mr. Arthur stated that because his

as-applied challenge to midazolam was based on the drugs rapid administration,

the harm could be significantly reduced by modifying the protocol to administer

midazolam more gradually, and to incorporate mechanisms to monitor the inmates

health. R.E. Tab 18 at 2-3. ADOC maintained that the protocol required no

modification. R.E. Tab 19. Accordingly, the parties reached an impasse, and

submitted their positions to the district court. Mr. Arthur also submitted a further

-17-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 28 of 73

expert declaration of a board-certified cardiologist, providing support for his

proposed modifications. R.E. Tab 11.

On April 21,2016, the district court identified a number of issues it

believed may not be in dispute, and a number of legal issues that required briefing.

R.E. Tab 16. Accordingly, the district court ordered ADOC to submit a motion for

judgment on the pleadings, and in the alternative, summary judgment. R.E. Tab

16. ADOC so moved, and Mr. Arthur opposed.

G.

Mr. Arthurs Motion for a New Trial

On April 14, 2016, the day before the First-Phase Opinion was

released, Mr. Arthurs counsel learned of new evidence. In a separate Eighth

Amendment challenge brought by other condemned inmates, the States

pharmacist expert, Dr. Daniel Buffingtonalso an ADOC expert in Mr. Arthurs

action (but who did not testify at the hearing due to the bifurcation order)

testified that he personally knew compounding pharmacists who would be willing

to compound pentobarbital for ADOC, and that to obtain pentobarbital, ADOC

would just have to ask. R.E. Tab 14 at 98:3-15; 101:6-102:12. Because this

evidence directly contradicted the (non-expert) evidence offered by the State in the

first-phase hearing, Mr. Arthur filed a motion for a new trial as to the availability

of pentobarbital on May 13, 2016. R.E. Tab 13.

-18-

Case: 16-15549

H.

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 29 of 73

The District Courts Subsequent Opinions

On July 19, 2016, the district court issued an opinion resolving

ADOCs motion for summary judgment and Mr. Arthurs motion for a new trial.

R.E. Tab 3. The district court granted summary judgment for ADOC, holding that

Mr. Arthur was obligated to plead and prove an alternative method of execution in

support of his as-applied challenge, and had failed to do so. R.E. Tab 3. The court

ruled that Mr. Arthurs proposed modifications to the existing midazolam-based

protocol were inadequate because he failed to offer expert medical evidence that

showed specific, detailed and concrete alternatives or modifications to the

protocol with precise procedures, amounts, times and frequencies of

implementation. R.E. Tab 3 at 24 (internal quotation marks omitted).

The district court also held that Mr. Arthur had failed to raise a

genuine issue of material fact concerning the risk posed by ADOCs protocol asapplied to Mr. Arthur. Mr. Arthur had relied primarily upon expert evidence from

a practicing cardiologist with decades of experience, but the district court excluded

this evidence under Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharm., Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

R.E. Tab 3 at 35-36. The district court reasoned that Mr. Arthurs expert was not

permitted to extrapolate his opinions on midazolam from a clinical dose to the dose

used in ADOCs protocol, and that the expert was unqualified because he had no

-19-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 30 of 73

experience administering midazolam at the potentially lethal dose called for in

ADOCs protocol. R.E. Tab 3 at 35-36.

The district court further denied Mr. Arthurs motion for a new trial,

crediting a declaration submitted by Dr. Buffington, wherein he supplemented

his deposition testimony by stating that he subsequently contacted a number of

pharmacists and they were either unable or unwilling to supply compounded

pentobarbital to ADOC. R.E. Tab at 41-42.

I.

Mr. Arthurs Execution Date

Two days after the First-Phase Opinion was released, the State moved

the Alabama Supreme Court to set an expedited execution date for Mr. Arthur

before any other pending motions to set an execution date are addressed. Mot. to

Reset Arthurs Execution Date, Ex parte Arthur, No. 1951985 (Ala. Jul. 21, 2016).

Thus, rather than seeking execution dates based on when the proceedings of

condemned inmates had been finalized, the State apparently put Mr. Arthur at the

top of the list and sought an execution date before any decision on his appeal. Mr.

Arthur opposed, and timely appealed the district courts judgment on August 18,

2016.

Despite Mr. Arthurs pending appeal, the Alabama Supreme Court on

September 14, 2016 set an execution date for November 3, 2016. R.E. Tab 7.

-20-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 31 of 73

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

I.A. The district court improperly denied Mr. Arthur leave to amend

his complaint to include the firing squad as an alternative method of execution. In

so doing, the district court incorrectly applied Glossip by requiring Mr. Arthur to

plead an alternative method that is expressly authorized by statute.

This

interpretation is untenable; if allowed to stand, it would permit states to

legislatively exempt themselves from Eighth Amendment scrutiny (by providing

for only a single method of execution) and create state-by-state variations in

Constitutional protections.

I.B. Despite Mr. Arthurs substantial showing that pentobarbital is a

feasible and readily implemented alternative execution drugincluding that the

active ingredient for pentobarbital is available for sale in the United States and a

number of pharmacies in Alabama are capable of compounding it, and that several

other states have used compounded pentobarbital recently in executionsthe

district court ruled that Mr. Arthur failed to show that this drug is an available

alternative. Indeed, the court essentially placed on Mr. Arthur the impossible

burden of procuring the drugs himselfwhich he had no practical ability to do

while simultaneously preventing him from obtaining discovery as to ADOCs

ability to obtain the drug. As well, the court relieved ADOC of the obligation to

undertake good-faith efforts to obtain pentobarbitalas Glossip demandsyet

-21-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 32 of 73

credited ADOCs half-hearted, insubstantial efforts to create a record of

unavailability.

II.A. Mr. Arthur offered unrebutted expert evidence that the

administration of midazolam, as directed by ADOCs lethal injection protocol,

would cause him to suffer a painful heart attack before being sedated. The district

court erroneously dismissed this claim on summary judgment by excluding the

unchallenged testimony of an eminently qualified cardiologist. The court reasoned

that the expert could not reliably extrapolate findings regarding a clinical dose of

midazolam to the massive overdose called for in ADOCs protocoleven though

such extrapolation was expressly sanctioned in Glossipand the expert was

unqualified because he had no personal experience administering a potentially

lethal overdose of midazolam. Both reasons are unsupportable.

II.B.

At the district courts request, Mr. Arthur proposed

modifications to ADOCs current protocol involving the use of midazolam that is

in ADOCs possession and therefore obviously readily available. The district

court nonetheless erroneously rejected this proposed alternative because Mr.

Arthurs medical expert refused to violate his ethical obligations and oath as a

physician by providing step-by-step execution instructions.

This holding

essentially renders it impossible to prove an available alternative and should be

rejected.

-22-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 33 of 73

III. This Court has made clear that substantial deviations from the

States execution protocol burden Mr. Arthurs right to Equal Protection under the

Fourteenth Amendment, Arthur, 674 F.3d at 1262, and Mr. Arthur made an

overwhelming showing that the State had, and would continue to, inadequately and

inconsistently apply its consciousness assessment.

The court erroneously

dismissed this claim by recasting it as an Eighth Amendment claim and thus

applied the wrong legal standardcontrary to this Courts instructions and the

district courts own prior rulings.

STANDARDS OF REVIEW

Argument I.A. (Mr. Arthurs Challenge to the Courts Erroneous

Decision to Deny Mr. Arthur Leave to Amend his Complaint to Allege the

Firing Squad as an Alternative Method of Execution). This Court generally

review[s] the district courts decision to deny leave to amend for an abuse of

discretion, but . . . will review de novo an order denying leave to amend on the

grounds of futility, because it is a conclusion of law that an amended complaint

would necessarily fail. City of Miami v. Wells Fargo & Co., 801 F.3d 1258, 1265

(11th Cir. 2015).

Moreover, in a capital case, the district court should be

particularly favorably disposed toward a petitioners motion to amend. Moore v.

Balkcom, 716 F.2d 1511, 1526 (11th Cir. 1983). Here, because the district courts

-23-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 34 of 73

denial of leave to amend was based on an error of law, it should be reviewed de

novo. City of Miami, 801 F.3d at 1265.

Arguments I.B. (Mr. Arthurs Challenge to the District Courts

Misapplication of Glossip) and III (Mr. Arthurs Challenge to the District

Courts Erroneous Dismissal of his Equal Protection Claim).

After a bench

trial, [this Court] review[s] the district courts conclusions of law de novo and the

district courts factual findings for clear error.

Proudfoot Consulting Co. v.

Gordon, 576 F.3d 1223, 1230 (11th Cir. 2009). Similarly, [t]he question whether

the district court correctly interpreted . . . controlling legal precedent is subject to

de novo review. United States v. Jones, 125 F.3d 1418, 1427 (11th Cir. 1997).

Under the clear error standard, [this Court] may reverse the district courts

findings of fact if, after viewing all the evidence, [the Court is] left with the

definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been committed. Travelers Prop.

Cas. Co. of Am. v. Moore, 763 F.3d 1265, 1268 (11th Cir. 2014).

A motion for a new trial is reviewed for abuse of discretion. Toole v.

Baxter Healthcare Corp., 235 F.3d 1307, 1316 (11th Cir. 2000)

Argument I.B.4 (Mr. Arthurs Challenge to the District Courts

Improper Denial of Discovery on ADOCs Sources of Lethal Injection Drugs

and Efforts To Procure Them). This Court review[s] for abuse of discretion the

district courts denial of discovery. Arthur v. Allen, 452 F.3d 1234, 1243 (11th

-24-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 35 of 73

Cir. 2006). [A] district court by definition abuses its discretion when it makes an

error of law. Id.

Argument II (Mr. Arthurs Challenge to the District Courts

Dismissal on Summary Judgment of Mr. Arthurs As-Applied Claim

Regarding His Unique Health Circumstances).

This Court review[s] de novo a summary judgment determination,

drawing all reasonable inferences in the light most favorable to the non-moving

party. Quigg v. Thomas Cty. Sch. Dist., 814 F.3d 1227, 1235 (11th Cir. 2016).

Summary judgment is only appropriate if a case is so one-sided that one party

must prevail as a matter of law. Id. Summary judgment may be inappropriate

even where the parties agree on the basic facts, but disagree about the factual

inferences that should be drawn from these facts. If reasonable minds might differ

on the inferences arising from undisputed facts, then the court should deny

summary judgment. Ellison v. Nw. Engg Co., 709 F.2d 681, 682 (11th Cir.

1983).

A district courts exclusion of expert evidence is reviewed for abuse

of discretion. United States v. Alabama Power Co., 730 F.3d 1278, 1282 (11th

Cir. 2013). However, it is not the role of the district court to make ultimate

conclusions as to the persuasiveness of the proffered evidence. Quiet Tech. DC-8,

Inc. v. Hurel-Dubois UK Ltd., 326 F.3d 1333, 1341 (11th Cir. 2003). The district

-25-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 36 of 73

courts gatekeeping role . . . is not intended to supplant the adversary system or

the role of the [factfinder]: vigorous cross-examination, presentation of contrary

evidence, and careful instruction on the burden of proof are the traditional and

appropriate means of attacking shaky but admissible evidence. Id.

ARGUMENT

I.

THE DISTRICT COURT MISINTERPRETED THE REQUIREMENT

TO PLEAD A FEASIBLE ALTERNATIVE METHOD OF

EXECUTION.

A.

The District Court Improperly Denied Mr. Arthur Leave to Plead

the Firing Squad as an Alternative Method of Execution.

After Glossip, Mr. Arthur sought leave to amend his complaint to

include the firing squad as an alternative method of execution. R.E. Tab 28. Mr.

Arthurs proposed amended complaint alleged that the firing squad was a known

and available alternative in the state of Alabama, that there are numerous people

employed by the State who have the training necessary to successfully perform an

execution by firing squad, and that the State already has a stockpile of both

weapons and ammunition.

R.E. Tab 6 135.

Additionally, Mr. Arthurs

proposed complaint alleged that execution by firing squad, if implemented

properly, would result in a substantially lesser risk of harm than the States

continued use of a three-drug protocol involving midazolam. R.E. Tab 6 136.

The State did not deny any of Mr. Arthurs allegations, but contended that the

-26-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 37 of 73

firing squad was not a feasible alternative under Glossip because it is not a

method contemplated by or provided in the Code of Alabama. R.E. Tab 26 at 8.

The district court adopted the States argument and denied Mr. Arthur

the opportunity to plead the firing squad as an alternative, based on the erroneous

reasoning that because execution by firing squad is not permitted by statute, it

therefore is not a method of execution that could be considered either feasible or

readily implemented by Alabama at this time. R.E. Tab 4 at 2.

1.

Glossip Does Not Require Alternative Methods of Execution

To Be Permitted by Statute.

The district courts ruling misconstrues Glossip.

In Glossip, the

Supreme Court expressly permitted inmates to challenge a method of execution by

pleading and proving a known and available alternative method of execution

that is feasible, readily implemented, and in fact significantly reduce[s] a

substantial risk of severe pain. 135 S. Ct. at 2737-38 (quoting Baze, 553 U.S. at

52) (alteration in original). Glossip does not suggest, much less require, that such

an alternative method must be statutorily authorized to be considered feasible or

readily implemented. By holding that Mr. Arthur cannot plead an alternative

method of execution if that method is not already permitted by statute, the

district court crafted out of whole cloth a prerequisite that was neither required nor

envisioned by Glossip.

-27-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 38 of 73

Indeed, the Glossip opinion itself contemplated the pleading of

alternatives that are not permitted by statute.

At issue in Glossip was

Oklahomas death penalty law, which provides in relevant part that [t]he

punishment of death shall be carried out by the administration of a lethal quantity

of a drug or drugs. Okla. Stat. tit. 22, 1014(A). Under the district courts

reasoning, only a drug or drugs would be permitted by statute in Oklahoma,

and thus, a petitioner would be barred from pleading anything else. Yet in Glossip,

the Supreme Court held that petitioners in that case had not identified any

available drug or drugs that could be used in place of those that Oklahoma is now

unable to obtain[, n]or have they shown a risk of pain so great that other

acceptable, available methods must be used.

135 S. Ct. at 2738 (emphasis

added). Accordingly, the Supreme Court indicated that petitioners could have

pleaded not only alternative drugs, but also other acceptable, available

methods of execution. Id. Indeed, in Glossip, the Supreme Court specifically

noted the constitutionality of the firing squad and electric chair. See id. at 2732.

The inescapable conclusion is that if a method of execution creates a risk of pain

that would violate the Eighth Amendment as compared to known and available

alternatives, those alternatives need not be part of a states existing legislative

scheme.

-28-

Case: 16-15549

2.

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 39 of 73

Adopting the District Courts Interpretation of Glossip Would

Lead to Absurd Consequences.

It is wholly unsurprising that the Supreme Court did not incorporate a

permitted by statute requirement in Glossip, given the objectionable

consequences that logically follow. Not only would states be permitted to shield

themselves from constitutional scrutiny merely by mandating single, specific

methods of execution, but the Eighth Amendment would suddenly take on dozens

of different meanings nationwide.

a.

The district courts ruling allows states to legislatively

exempt themselves from Eighth Amendment review.

Glossip made clear that as long as condemned prisoners plead an

available alternative, they have the right to challenge a method of execution that

would produce a significant risk of serious harm. See Glossip, 135 S. Ct. at 2746

(stating that it was outlandish to suggest prisoners are not able to challenge

inhumane execution methods under the Courts ruling). Affirming the district

courts judgment would negate that right by giving states the perverse incentive to

limit their death penalty statutes to one specific method so as to foreclose any

constitutional challenge. For example, a state could mandate a three-drug protocol

using midazolam hydrochloride, rocuronium bromide, and potassium chloride (i.e.,

ADOCs current protocol). If the state did not specifically delineate alternatives in

a statute, then that would instantly defeat all conceivable method-of-execution

-29-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 40 of 73

challenges. To take a more extreme example, if a state legislated burning at the

stake as the only permissible method of execution, then no alternatives would be

permitted, and no challenge possible. The path to proving an Eighth Amendment

violation provided for in Glossip would then be illusory and the rule instead would

be:

if a state provides for a single method of execution, that method is

constitutional.7

The very real impact of the district courts ruling, if applied by other

courts, would be felt immediately in states that already provide for a narrow range

of statutorily acceptable options for carrying out the death penalty. For example,

the Montana lethal injection statute requires use of an ultra-fast-acting

barbiturate. Smith v. Montana, 2015 WL 5827252, at *2 (Mont. Dist. Ct. Oct 6,

2015).8 One notable drug that is not ultra-fast-acting is pentobarbital, which is

used by 14 states as part of their lethal injection protocols. See id. at *4. Under the

The district court also never provided a principled basis for why it was

drawing the line at permitted by statute. The district court could have just as

easilyand arbitrarilydecreed that an alternative method of execution must be

permitted by law. And since ADOC has delegated authority to determine the

only execution protocol permitted by law, every conceivable alternative to the

current protocol would thus be unavailable. This is, of course, an absurd result

permitting the whim of the executive branch to dictate constitutional standards

but the permitted by statute requirement is conceptually indistinguishable.

8

Several other states death penalty laws provide for equally specific

protocols without contemplating alternatives. See, e.g., Miss. Code Ann. 99-1951; Colo. Rev. Stat. 18-1.3-1202; Or. Rev. Stat. 137.473.

-30-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 41 of 73

district courts interpretation of Glossip, a petitioner in Montana would be

precluded from pleading as an alternative the most widely used form of execution

in the country. That cannot have been the intention of the Glossip Court.

Here, the district courts erroneous ruling denying Mr. Arthur the

opportunity to plead the firing squad as an alternative method of execution

despite its practical availability and use in this country for over a centuryhas

resulted in the ultimate dismissal of his Eighth Amendment challenge to the States

three-drug protocol without review of the evidence demonstrating the substantial

risks of that protocol, including as compared to the firing squad.

b.

The district courts holding will result in state-by-state

variation in federal constitutional rights.

Allowing the district courts decision to stand would also necessarily

mean that the Eighth Amendment has a different meaning in each state. For

example, as discussed above, under the district courts logic, a Montana petitioner

would be barred from pleading pentobarbital as an alternative. Yet in Oklahoma,

where the states lethal injection statute mandates execution by any drug or

drugs, a petitioner would face no such impediment. This outcome violates the

centuries-old basic tenet that constitutional rights should be interpreted uniformly

throughout the country. See Martin v. Hunters Lessee, 14 U.S. (1 Wheat.) 304,

348 (1816).

-31-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 42 of 73

Indeed, courts have specifically rejected the argument that a state-bystate standard should apply when evaluating Eighth Amendment claims, . . .

because such a state-by-state standard would aggravate regional differences in the

application of a national standard. United States v. Johnson, 900 F. Supp. 2d 949,

963 (N.D. Iowa 2012); see also United States v. Jacques, 2011 WL 3881033, at *4

(D. Vt. Sept. 2, 2011) ([A]pplying a state-based standard in evaluating Eighth

Amendment claims . . . would effectively be sanctioning and contributing to

geographic disparities in application of the federal death penalty.). There simply

is no compelling reason to encourage a discordant patchwork of constitutional

rights.

3.

Even if Glossip Does Require that an Alternative be Permitted

by Statute, Alabamas Death Penalty Statute Authorizes the

Firing Squad.

Even if Glossip required inmates to plead alternative methods of

execution that a state statute permits (it does not), Alabamas lethal injection

statute does permit the use of the firing squad.

The statutes savings clause

provides that if lethal injection or electrocution is held unconstitutional, all

persons sentenced to death for a capital crime shall be executed by any

constitutional method of execution. Ala. Code 15-18-82.1(c) (emphasis added);

see also Arcia v. Fla. Secy of State, 772 F.3d 1335, 1344 (11th Cir. 2014)

([A]ny means all.). As the Supreme Court recognized in Glossip, the firing

-32-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 43 of 73

squad is a constitutional method of execution. 135 S. Ct. at 2732, 2739 (citing

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130, 134-35 (1879)). Thus, if lethal injection is held

unconstitutional, Alabamas lethal injection statute allows the use of the firing

squad.9

The district court did not offer any reason why Alabamas savings

clause is inapplicable in Mr. Arthurs case.

R.E. Tab 25.

However, when

presented with this argument in another case challenging Alabamas method-ofexecution, the district court reasoned that because the firing squad is not permitted

by statute in Alabama absent a declaration that Alabamas current method is

unconstitutional, implementing [the firing squad] without lethal injection and

electrocution first being declared unconstitutional would require a statutory

amendment. Boyd v. Myers, No. 14-cv-1017, Dkt. # 50 at 11 (M.D. Ala. Oct. 7,

2015). This interpretation creates a Catch-22 that nullifies the savings clause of

Alabamas statute: to prove that lethal injection is unconstitutional, a condemned

inmate must plead a constitutional alternative method of execution, Glossip,

135 S. Ct. at 2737; but according to the district courts reasoning, such inmate

cannot plead any constitutional method[s] permitted by the savings clause

9

Based on the record in this proceeding, the State seems to contend that the

only manner in which Alabama can carry out lethal injection is according to its

current protocol. Accordingly, a finding that ADOCs protocol is unconstitutional

(and that the alternative lethal injection methods proposed by Mr. Arthur are

unavailable) would implicate the savings clause.

-33-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 44 of 73

without first satisfying both of Glossips requirements: the challenged execution

method is unconstitutional and a feasible alternative method exists. The district

courts reading finds no support in Glossip and strips the broad constitutional

savings clause in Ala. Code 15-18-82.1(c) of its natural meaning. See Ali v. Fed.

Bureau of Prisons, 552 U.S. 214, 218-19 (2008) (noting that the word any has

an expansive meaning). Such a construction also runs afoul of the time-honored

canon of construction that [courts] should disfavor interpretations of statutes that

render language superfluous. In re Rothstein, Rosenfeldt, Adler, P.A., 717 F.3d

1205, 1214 (11th Cir. 2013).

Additionally, the district courts interpretation ignores the intent of

Glossip: the alternative method requirement in Glossip was designed to ensure

that a state wishing to do so may implement the death penalty in a constitutional

manner and prevent gamesmanship in Eighth Amendment challenges.

See

Glossip, 135 S. Ct. at 2732-33. It was not intended to limit Eighth Amendment

claims to the selection of an alternative allowed by existing state statute.

-34-

Case: 16-15549

B.

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 45 of 73

The District Court Erred In Dismissing Mr. Arthurs Substantial

Evidence that Pentobarbital Is an Available Alternative to

Midazolam.

1.

The District Court Misconstrued the Burden Imposed by

Glossip by Effectively Requiring Mr. Arthur To Obtain an

Alternative Execution Drug.

In Baze, Chief Justice Roberts explained that a method of execution

challenger could propose any feasible and readily implemented alternative.

Baze, 553 U.S. at 52. The meaning of these terms is no secret. As the Supreme

Court has previously explained, [t]he plain meaning of the word feasible . . . [is]

capable of being done, executed, or effected. Am. Textile Mfrs. Inst., Inc. v.

Donovan, 452 U.S. 490, 508-509 (1981) (quoting Websters Third New

International Dictionary of the English Language 831 (1976)).

Similarly,

Glossips readily implemented requirement should be read to mean that such an

alternative is reasonably practicable under the circumstances. Cf. United States v.

One TRW, Model M14, 7.62 Caliber Rifle, 441 F.3d 416, 422 (6th Cir. 2006)

([R]eadily is a relative term, one that describes a process that is fairly or

reasonably efficient, quick, and easy, but not necessarily the most efficient,

speedy, or easy process. (citing Websters Third New International Dictionary of

the English Language 1889 (1981)) (emphasis in original)).10

10

Under the district courts formulation, feasible [and] readily implemented

means known and available. R.E. Tab 2 at 9 (citation omitted).

-35-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 46 of 73

The Supreme Court certainly did not impose a heightened requirement

that a method-of-execution challenger procure an alternative or identify a

specific source for an alternative. Rather, all Baze and Glossip require is for Mr.

Arthur to identify an alternative [method of execution] that is feasible [and]

readily implemented. Glossip, 135 S. Ct. at 2737 (quoting Baze, 553 U.S. at 52)

(emphasis added). Accordingly, Mr. Arthur should have been able to satisfy his

burden by identify[ing] an alternative method of execution, id., that could be

carried out by the State. See Donovan, 452 U.S. at 508.

Mr. Arthur showed exactly this. In particular, Mr. Arthur offered the

expert testimony of Dr. Gaylen M. Zentner, Ph.D., a pharmaceutical chemist and

registered pharmacist with over three decades of experience in the pharmaceutical

industry. The district court found Dr. Zentners testimony credible. R.E. Tab 2 at

14.11

With respect to the ready availability of pentobarbital, Dr. Zentner

testified, as the district court summarized, that:

(1) no active patents cover

[pentobarbital sodium], meaning that anyone who has the ingredients can make it;

(2) at least four other states have been able to locate sources for compounded

11

To the extent ADOC relies on this Courts decision in Brooks v. Warden,

810 F.3d 812 (11th Cir. 2016), Mr. Arthurs showing far exceeds the showing

made in that case, specifically by providing detailed evidence on capable

pharmacies in Alabama that are equipped to prepare compounded pentobarbital.

-36-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 47 of 73

pentobarbital for use in executions over the past year; (3) creating compounded

pentobarbital [is] a straightforward process and [a]ny pharmacy in any state that

desires to compound pentobarbital could implement that straightforward

process; (4) there is a company in the United States that listed pentobarbital

sodium, the active ingredient for compounded pentobarbital, as among its

products for sale; (5) there are overseas suppliers of pentobarbital sodium;

(6) pentobarbital sodium could be produced by drug synthesis labs in the United

States; and (7) at least two accredited pharmacies in Alabama agreed when

contacted by Dr. Zentner that they had the facilities necessary to do sterile

compounding. R.E. Tab 2 at 11-14. In sum, as to the availability of pentobarbital

to ADOC, Dr. Zentners unrebutted testimony was that there are compounding

pharmacies that have the skills and licenses to perform sterile compounding of

pentobarbital sodium. Therefore, the feasibility for producing a sterile preparation

of pentobarbital sodium does exist.

R.E. Tab 22 at 219:13-16.

The State

presented no expert evidence to the contrary.

Despite this, the district court concluded that Mr. Arthur had not met

his burden because he had presented evidence only of alternatives that should,

could or may be available. R.E. Tab 22 at 20. This conclusion is flawed for

multiple reasons.

-37-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 48 of 73

First, if an identified alternative should, could or may be available,

based on unrebutted and unchallenged expert evidence, then it is capable of being

done, and therefore necessarily feasible within the plain meaning of that word.

See Donovan, 452 U.S. at 508.

Similarly, if an alternative is known and

practicable, it can be readily implemented without unreasonably burdening the

State. But by going furtherapparently requiring Mr. Arthur to identify a specific

willing source, or actually procure an alternative, R.E. Tab 2 at 20)the district

court imposed a much more stringent standard than required by Glossip, one that

would be nigh impossible for a condemned inmate to meet.12

Second, despite the district courts characterization, the unchallenged

evidence was not merely that pentobarbital may be available, but in fact that it

is available, R.E. Tab 22 at 219:12, because all its ingredients are readily

available, R.E. Tab 22 at 205:23, and any qualified pharmacist can perform the

easy and straightforward compounding process necessary to create the drug, R.E.

Tab 22 at 208:20; see generally R.E. Tab 22 at 205-219.

This evidence is

confirmed by the fact that other states have obtained and used compounded

pentobarbital. See R.E. Tab 22 at 218:7-10); R.E. Tab 51.

12

As further explained below, Section II.B., infra, the district court later

further expounded on this to require the pleading and proof of an alternative

protocol with a precise procedure, amount, time and frequencies of

implementation. R.E. Tab 3 at 24-25. All of this demonstrates that the district

court failed to properly apply Glossip.

-38-

Case: 16-15549

Date Filed: 09/26/2016

Page: 49 of 73

The district court further erred in adhering to its conclusion even

when, after the hearing, one of defendants own experts, Daniel Buffington, Pharm.

D., testified in another proceeding that he had met other pharmacists who told him

that they would be willing to compound pentobarbital for use in lethal

injections. R.E. Tab 3 at 41 (quoting R.E. Tab 9 2). This concession further

confirmed the testimony of Dr. Zentner that pentobarbital is, in fact, available to

ADOC as a compounded drug. Nonetheless, the district court allowed ADOC to

gloss over Dr. Buffingtons concession through a supplemental declaration (not

subject to cross-examination), in which Dr. Buffington stated that he had

subsequently contacted certain pharmacists who, he said, told him they were

unable or unwilling to supply compounded pentobarbital to ADOC. R.E. Tab 9

7.13 The district court abused its discretion by disregarding Dr. Buffingtons

admission at deposition, which should have, at the very least, resulted in a new

trial. See Branca v. Sec. Ben. Life Ins. Co., 789 F.2d 1511, 1512 (11th Cir. 1986).

13

However, certain of the pharmacists indicated not that they were unwilling, but

that they would have difficulty with access to the pharmaceutical supplies and

raw materials needed to compounded [sic] pentobarbital. R.E. Tab 9 7. There

is no reason the State could not have assisted such apparently willing pharmacists

to obtain the necessary ingredients.

-39-

Case: 16-15549

2.

Date Filed: 09/26/2016