Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Holland's Theory (1959-1999) - 40 Years of Research and Application

Transféré par

Thais Lanutti ForcioneTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Holland's Theory (1959-1999) - 40 Years of Research and Application

Transféré par

Thais Lanutti ForcioneDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

JOHN L.

HOLLAND

Journal of Vocational Behavior 55, 1 4 (1999)

Article ID jvbe.1999.1694, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on

INTRODUCTION

Hollands Theory (1959 1999): 40 Years of Research

and Application

Mark L. Savickas

Behavioral Sciences Department, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine

and

Gary D. Gottfredson

Gottfredson Associates, Inc.

During World War II, John L. Holland served in the Army for 3 years and 5

months. Working as a personnel clerk, he began to think that just a few types

were required to account for much of the regularity he noticed in soldiers

occupational histories. Following the war, Holland developed a classification that

research has shown does just that. He began work on his classification system at

the University of Minnesota with the encouragement of his Ph.D. advisor, John

Darley. At Minnesota, Holland became convinced that college students with

different interests have different personalities. He generalized this conclusion to

occupational groups while working as a college instructor and vocational counselor at Western Reserve University (1950 1953). Holland began studying

which personalities fit which occupations by formulating personality sketches of

people employed in different occupations using the scoring keys from the Strong

Interest Inventory as his data. These interpretive character sketches eventually

became the fomulations in Hollands theory of personality types and work

environments, first published in 1959.

In that seminal article about his theory, Holland articulated the two goals that

motivated him to formulate the theory. First, he sought to comprehend and

integrate existing knowledge about vocational choice. Second, he hoped that the

theory would prompt further research. Within a few years after the theory was

published, it became obvious that Holland achieved both of these goals, and by

1991 Borgen concluded that research on Hollands theory is voluminous and

unabating (p. 275). From our perspective four decades after publication of the

1

0001-8791/99 $30.00

Copyright 1999 by Academic Press

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

INTRODUCTION

theory, we conclude that Hollands theory has been a surpassing achievement in

vocational psychology. In addition to prompting a tremendous amount of empirical research in vocational and I/O psychology, the theory has provided major

breakthroughs in conceptualizing vocational interests and career decision making, constructing interest inventories, organizing occupational information, counseling for career development, and structuring career education curricula.

As Borgen (1999) recently stated, Holland wrote the book on interest measurement. His creative contributions have been integrative for more than 35

years . . .. His assertion that interests and personality are related stakes out the

center ground of theoretical and counseling integration (p. 405). Appropriately,

since its publication in 1973 , Hollands book entitled Making Vocational

Choices has been by far the most cited work in the field of vocational psychology. Hollands RIASEC hexagon is the icon for vocational psychology; it even

adorns the cover of the Journal of Vocational Behavior. More importantly, this

structural arrangement of six personality types into a hexagon is one of the most

well-replicated findings in the history of vocational psychology (Rounds, 1995).

On the 40th anniversary of the theorys first statement, this special issue of the

Journal of Vocational Behavior documents and celebrates how Holland has

elaborated his theory during the past four decades as well as looks ahead to

further developments of the theory. This festschrift begins with an article by G.

Gottfredson that discusses Hollands major contributions to vocational psychology. Gottfredson explains how Hollands approach to science enabled Holland to

transform and improve the delivery of vocational assistance worldwide.

Gottfredsons overview is followed by two articles that address the bedrock of

Hollands theorypersonalities in environments. First, Hogan and Blake compare Hollands six types of vocational personalities to the Five-Factor Model of

personality (FFM). They conclude that Hollands interest inventories measure

identity, that is, a persons own aspirations, hopes, or dreams, whereas personality inventories measure reputation, that is, personality from the observers

point of view. Hogan and Blake offer the heuristic conclusion that Holland has

provided a taxonomy of identity choices from the actors perspective in the same

way that the FFM offers a taxonomy of reputation from the observers perspective. In the second article on personalities in environments, L. Gottfredson and

Richards sagaciously concentrate on a core element of Hollands theory, one that

researchers and practitioners too often disregardthe environmental formulations. They show how Holland has moved his theory toward an ecological

perspective for building a science of environments.

One of Hollands best ideas was to describe occupations in terms of the

psychological attributes of their incumbents, which enabled him to characterize

personality types and work environments using parallel constructs and parallel

taxonomies. This contribution appears to be even more important in contemporary society as the content of jobs rapidly changes (Dawis, 1996). Occupational

information systems based on job content require constant updating and major

INTRODUCTION

revisions, whereas Hollands method of describing occupations based on psychological attributes remains rather stable and needs only minor revisions as the

world of work changes. This may be why, as McDaniel explains in his article,

Hollands occupational taxonomy is used in about 50 different career information

delivery systems, including two prominent systemsthe Department of Defenses ASVAB Career Exploration Program and the Department of Labors

O*NET sytem.

In addition to organizing occupational information, Hollands theory has

come to dominate the design of interest inventories, even reshaping the

venerable Strong Interest Inventory. Borgen (1991) cited Campbell and

Hollands (1972) application of Hollands theory to Strongs data as one of

the remarkable advances in interest measurement because it integrated two

diverse paradigmsStrongs dustbowl empiricism and Hollands conceptual

abstractions. Of course the instruments developed by Holland and his colleagues, such as the Self-Directed Search and Vocational Preference Inventory, continue to be among the most popular inventories used by career

counselors. Campbell and Borgen, in this issue, explain how Hollands

hexagon has brought structure, organization, and simplification to interest

measurement. In the next article, Reardon and Lentz discuss how counselors

use Hollands model and methods in career assessment.

The article by Rayman and Atanasoff explains why Hollands theory has been

so useful for practitioners. The authors also spell out the features of the SelfDirected Search and other tools developed by Holland that account for their

success. Among these useful features are the way the classification organizes

information and a transparent, self-scored inventory intended to have effects on

users. Muchinskys article also shows why Hollands theory has been so useful

to I/O psychologists as they address issues of person environment fit.

In the next article, Chartrand and Walsh remind readers why person

environment fit remains a central tenet of Hollands theorysatisfaction and

success depend on the goodness of fit between the worker and the job. Chartrand

and Walsh review some of the voluminous research that has examined the

validity of this congruence hypothesis and then analyze the difficulties in measuring person environment fit.

Making congruent choices stymies many individuals, causing them to seek

career counseling to resolve their difficulties in deciding. Hollands continuing

interest in the problem of indecision resulted in a major innovation when he

reformulated the dichotomy between decided and undecided into a continuum

and then linked that continuum to a new construct, namely vocational identity.

Osipow discusses how Hollands construct of vocational identity emerged from

his persistent attempts to conceptualize and measure career indecision.

In addition to advancing a heuristic theory, Holland has been a generative

mentor in advancing the careers of his students and colleagues, as attested to

by Astin in the final article in this issue. The festschrift concludes with

INTRODUCTION

Hollands bibliographya resource for the young scholars who will extend

Hollands theory for decades to come. For the contributions documented in

this volume and more, we thank the consummate vocational psychologist

John L. Holland.

REFERENCES

Borgen, F. H. (1991). Megatrends and milestones in vocational behavior: A twenty-year counseling

psychology retrospective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 39, 263290.

Borgen, F. H. (1999). New horizons in interest theory and measurement: Toward expanded meaning.

In M. L. Savickas & A. R. Spokane (Eds.), Vocational interests: Meaning measurement, and

counseling use (pp. 383 411). Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black Publishing.

Campbell, D. P., & Holland, J. L. (1972). A merger in vocational interest research: Applying

Hollands theory to Strongs data. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 2, 353376.

Dawis, R. W. (1996). Vocational psychology, vocational adjustment, and the workforce: Some

familiar and unanticipated consequences. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 2, 229 248.

Holland, J. L. (1959). A theory of vocational choice. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 6, 35 44.

Holland, J. L. (1966). Making vocational choices. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Rounds, J. B. (1995). Vocational interests: Evaluating structural hypotheses. In D. Lubinski & R. V.

Dawis (Eds.), Assessing individual differences (pp. 177232). Palo Alto,CA: Davies-Black

Publishing.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Linux For Beginners - Shane BlackDocument165 pagesLinux For Beginners - Shane BlackQuod Antichristus100% (1)

- Reverse Engineering in Rapid PrototypeDocument15 pagesReverse Engineering in Rapid PrototypeChaubey Ajay67% (3)

- Effectiveness of A Career Time Perspective InterventionDocument14 pagesEffectiveness of A Career Time Perspective InterventionThais Lanutti ForcionePas encore d'évaluation

- 1934 PARIS AIRSHOW REPORT - Part1 PDFDocument11 pages1934 PARIS AIRSHOW REPORT - Part1 PDFstarsalingsoul8000Pas encore d'évaluation

- Catalog Celule Siemens 8DJHDocument80 pagesCatalog Celule Siemens 8DJHAlexandru HalauPas encore d'évaluation

- D - MMDA vs. Concerned Residents of Manila BayDocument13 pagesD - MMDA vs. Concerned Residents of Manila BayMia VinuyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Identity Construction and Career Development Interventions With Emerging AdultsDocument7 pagesIdentity Construction and Career Development Interventions With Emerging AdultsThais Lanutti ForcionePas encore d'évaluation

- Identity in Vocational DevelopmentDocument9 pagesIdentity in Vocational DevelopmentThais Lanutti ForcionePas encore d'évaluation

- Entrevista Com SavickasDocument18 pagesEntrevista Com SavickasThais Lanutti ForcionePas encore d'évaluation

- Missouri Courts Appellate PracticeDocument27 pagesMissouri Courts Appellate PracticeGenePas encore d'évaluation

- Online Learning Interactions During The Level I Covid-19 Pandemic Community Activity Restriction: What Are The Important Determinants and Complaints?Document16 pagesOnline Learning Interactions During The Level I Covid-19 Pandemic Community Activity Restriction: What Are The Important Determinants and Complaints?Maulana Adhi Setyo NugrohoPas encore d'évaluation

- QUIZ Group 1 Answer KeyDocument3 pagesQUIZ Group 1 Answer KeyJames MercadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduce Letter - CV IDS (Company Profile)Document13 pagesIntroduce Letter - CV IDS (Company Profile)katnissPas encore d'évaluation

- Final ExamSOMFinal 2016 FinalDocument11 pagesFinal ExamSOMFinal 2016 Finalkhalil alhatabPas encore d'évaluation

- 4th Sem Electrical AliiedDocument1 page4th Sem Electrical AliiedSam ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Underwater Wellhead Casing Patch: Instruction Manual 6480Document8 pagesUnderwater Wellhead Casing Patch: Instruction Manual 6480Ragui StephanosPas encore d'évaluation

- Wendi C. Lassiter, Raleigh NC ResumeDocument2 pagesWendi C. Lassiter, Raleigh NC ResumewendilassiterPas encore d'évaluation

- Javascript Applications Nodejs React MongodbDocument452 pagesJavascript Applications Nodejs React MongodbFrancisco Miguel Estrada PastorPas encore d'évaluation

- 004-PA-16 Technosheet ICP2 LRDocument2 pages004-PA-16 Technosheet ICP2 LRHossam Mostafa100% (1)

- Process States in Operating SystemDocument4 pagesProcess States in Operating SystemKushal Roy ChowdhuryPas encore d'évaluation

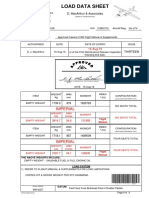

- Load Data Sheet: ImperialDocument3 pagesLoad Data Sheet: ImperialLaurean Cub BlankPas encore d'évaluation

- PVAI VPO - Membership FormDocument8 pagesPVAI VPO - Membership FormRajeevSangamPas encore d'évaluation

- Aisladores 34.5 KV Marca Gamma PDFDocument8 pagesAisladores 34.5 KV Marca Gamma PDFRicardo MotiñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gabby Resume1Document3 pagesGabby Resume1Kidradj GeronPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Media Marketing Advice To Get You StartedmhogmDocument2 pagesSocial Media Marketing Advice To Get You StartedmhogmSanchezCowan8Pas encore d'évaluation

- Check Fraud Running Rampant in 2023 Insights ArticleDocument4 pagesCheck Fraud Running Rampant in 2023 Insights ArticleJames Brown bitchPas encore d'évaluation

- Exp. 5 - Terminal Characteristis and Parallel Operation of Single Phase Transformers.Document7 pagesExp. 5 - Terminal Characteristis and Parallel Operation of Single Phase Transformers.AbhishEk SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Historical Development of AccountingDocument25 pagesHistorical Development of AccountingstrifehartPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Insurance in Switzerland ETHDocument57 pagesHealth Insurance in Switzerland ETHguzman87Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1.1. Evolution of Cloud ComputingDocument31 pages1.1. Evolution of Cloud Computing19epci022 Prem Kumaar RPas encore d'évaluation

- 2021S-EPM 1163 - Day-11-Unit-8 ProcMgmt-AODADocument13 pages2021S-EPM 1163 - Day-11-Unit-8 ProcMgmt-AODAehsan ershadPas encore d'évaluation

- Sophia Program For Sustainable FuturesDocument128 pagesSophia Program For Sustainable FuturesfraspaPas encore d'évaluation

- Audit Certificate: (On Chartered Accountant Firm's Letter Head)Document3 pagesAudit Certificate: (On Chartered Accountant Firm's Letter Head)manjeet mishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Efs151 Parts ManualDocument78 pagesEfs151 Parts ManualRafael VanegasPas encore d'évaluation