Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Feminism's Futures: The Limits and Ambitions of Rokeya's Dream

Transféré par

Sumeet SahooTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Feminism's Futures: The Limits and Ambitions of Rokeya's Dream

Transféré par

Sumeet SahooDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

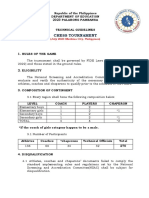

PERSPECTIVES

Feminisms Futures

The Limits and Ambitions

of Rokeyas Dream

Rajeswari Sunder Rajan

What do feminists want? What

visions of an ideal society have

we conceptualised or dreamt of?

What are the possibilities and

limits of iterations of a feminist

futurity? Even as we ask,

however, we are brought up short

by a more fundamental question:

is such a teleological conception

of any theory or social movement

however we define feminism

valid? Can we expect feminism to

function with a single blueprint of

an ideal political order or society

to come?

Rajeswari Sunder Rajan (rajeswari.sunderrajan@

googlemail.com) teaches at New York University.

Economic & Political Weekly

EPW

OCTOBER 10, 2015

1 Begum Rokeya

egum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain,

the author of Sultanas Dream,

is one of our feminist mothers,

and a writer for our times as much as she

was for her own. Her short life was filled

with remarkable achievements as writer,

journalist, educationist and pioneering

reformer of Bengali Muslim society in

the early 20th century.

Begum Rokeya was born in 1880 and

died in 1932. Born into a wealthy upperclass zamindari family in Rangpur District in present-day Bangladesh, to an

orthodox mother and a strict traditional

father who did not encourage womens

education, Rokeya and her sister nevertheless managed to learn Bangla and

English with the help and encouragement of their brothers. She was married

off at 16 to a widower many years older

than her, Syed Sakhawat Hossain.

Sakhawat Hossain was a highly educated man, and a civil servant. The critic

Roushan Jahan describes him as a man

of liberal attitude (1988: 39). He urged

his wife to go out into society, provided

her with books, encouraged her writing

and supported the cause of womens

education. Their married life was a short

one howeverSakhawat died in 1909

after a long and painful illness. He left

Rokeya a sizeable fortune with which

to start a girls school, which she did,

first in Bhagalpur and then in Calcutta,

encountering along the way a great deal

of opposition and criticism from her

community, and even from the parents

of her students.

Starting with only eight students the

Sakhawat Memorial Girls School in

Calcutta grew to be a thriving institution.

It continues to serve the cause of the

education of girls to this day, more than

vol l no 41

a hundred years later, a fitting memorial

as Jahan writes, to her wonderful husband as well as Rokeya herself (1988: 41).

In 1916 she founded a Muslim Womens

Association, going among poor Muslim

women and offering them financial

assistance, literacy classes and shelter.

She had begun writing for various

publications as early as 1903, and continued to write essays, stories, tracts

and fiction to the end of her life. In her

writing as in her other public work,

Rokeya addressed the problem of womens, especially Muslim womens, narrow

domestic lives in seclusion, campaigning

for their greater participation in public

life chiefly through education. She

addressed women readers directly in

her writings, using reason and persuasion to convince them of the harm of

confinement, endowing them with the

agency of their own emancipation. In

1973, the Bangla Academy collected her

scattered writings and published them

as Rokeya Racnavali, a sign of her iconic

status as intellectual, reformer, educationist and philanthropist in present-day

Bangladesh.

I have to confess that I know only a

portion of Rokeyas prolific writings in

Bangla through the few available translations. In this essay however I will be

focusing on Sultanas Dream, a text

written originally and uniquely, in English, and now firmly established in the

feminist literary canon. It is a short fable, only a little over 10 pages long,

which Rokeya wrote in 1905. Roushan

Jahan relies on Rokeyas own account of

how she came to write the story during

an idle interlude when she was alone at

home. Her writing was partly to demonstrate her proficiency in English to her

non-Bengali husband, Jahan surmises;

he was her immediate and appreciative

audience (1988: 1). Although this was

to be her sole attempt to write in English,

she had already begun to publish strongly

worded articles in various Bengali

journals protesting womens lack of

opportunities, and would also go on to

write several pieces of fantastical fiction:

so there is a thematic continuity in her

work. The story was first published

39

PERSPECTIVES

in the Indian Ladies Magazine, a

Madras-based English periodical, and

later republished in 1908 in book form

by a Calcutta publisher. As the title indicates, it narrates a fantasy dreamt by a

young woman, Sultana. In her dream

Sultana visits an unusual land that she

calls Ladyland governed and run solely

by women, while the men are confined

to the zenana. In this country Sultana

encounters perfect order, natural beauty

and harmony everywhere, all achieved

through technological advances and the

scientific knowledge that the women

have acquired. A feminist tract in the

generic form of a science fiction utopia

raises for us a number of reflections about

what I have called feminisms futures.

2 What Do Feminists Want?

Through the examination of Rokeyas

dream that I undertake here, I wish to

engage the question of feminisms ends

anew. The ends of feminism, in terms of

the futures that feminism has envisaged, and the end of feminism, as an

aspect of its futurity, are connected.

When and how will the longest revolution, as Juliet Mitchell (1984) called it,

end? What would it have achieved at

its conclusion?

Feminism is paradoxically situated

today. One American feminist famously

diagnosed feminisms defeat in a political climate in which a dominant moral

right asserts the triumph of family and

family values over womens careers and

legal rights (Faludi 1991). More recently

however, a popular American journalist

announced the sensational end of men

and rise of women, attributing both

phenomena to the current crisis of capitalism and to changes in reproductive

technologies (Rosin 2010). In Britain the

end of feminism has been explained in

terms of a post-feminismits goals have

ostensibly already been reached and it

has nowhere further to go (McRobbie

2004). From a different perspective

however feminism is pronounced a success (although many gender inequalities remain). Feminism is taking powerful new forms, which make it unrecognisable to some (Walby 2011: 1).

All this in the advanced industrial

West. In other parts of the world,

40

however, it seems as if feminism has

never been heard of, so unchecked and

rampant is misogynistic violence against

women. In the Indian subcontinent two

incidents of unspeakably brutal violence

committed against women in the recent

past (although neither is unique) have

awakened the conscience of our societies in an unprecedented way. The world

followed the fates of the victims for

weeks, with pity and terror. The survival

of one woman and the death of the other

have been deeply cathartic; and they

have been attended by lessons, both

moral and political, that we are still trying to absorb.1 In light of the widespread

realisation that has come in their wake,

that women have been and continue to be

subjected to violence by men on the

grounds of their gender, the demand of

feministsand no longer feminists

alonethat such violence cease has

come to seem a matter of the simplest

humanitarianism, even of a basic humanity. All that women ask, it seems, is that

they not be hurt. It is the modesty, not to

say abjection, of this demand that should

lead us to ask what do we, as feminists,

want for women?

What do feminists want? What visions

of an ideal society have we conceptualised or dreamt of? What are the possibilities and limits of iterations of a feminist futurity? Even as we ask, however,

we are brought up short by a more fundamental question: is such a teleological

conception of any theory or social movementhowever we define feminism

valid? Can we expect feminism to function

with a single blueprint of an ideal political order or society to come? Feminism

has been identified in terms of historical

phasesfirst wave, second wave, third

wave; it has also been interpreted differently by different constituencies, each

marked by a distinctive set of imperatives. Therefore feminisms future and

feminist futures, it might be argued, are

contingent on changing historical conditions and on the divergent agendas of a

non-unitary constituency conceptualised

under the rubric of women. In seeking

the feminist equivalent of Marxist classless

society as telos and revolutionary praxis

as method, would feminism then be

barking up the wrong tree?

We could say that feminism is primarily a form of critique rather than a programme. It has, variously, sought to

demystify difference, to isolate the

sources of womens subordination, to

identify patriarchy as a universal

regime of male domination, to analyse

its roots, and to deconstruct the sexgender system. Critique finds its limits in

an implicit reformism, the rectification

of the wrongs it uncovers.

Here is what I mean. Feminist analysis

of the condition of women has for the

most part been articulated in terms of

the following negative existential aspects:

discrimination; oppression; exploitation;

subordination; dispossession; powerlessness; violence (this is not a comprehensive list). Such a critique assumes the

implicit demand that the terms should

be altered if not reversed: thus equality

(in response to discrimination); emancipation (from forms of oppression); justice (freedom from exploitation); domination (as reversal of subordination);

ownership of property (as against dispossession); power (versus powerlessness); and counter-violence as the response to violence. And yet several of

these terms have hardly been pressed

into service in the context of feminism:

not domination; not power;2 not even

ownership of property; and certainly

not counter-violence.

Feminisms demands have for the

most part been coded instead in terms of

reform, to be achieved by legislative fiat

or mind-changing education or both.

Full-fledged opposition to the status quo

is rarely articulated and feminist futures

are not predicated on an overthrow of

existing economic, social or political

arrangements. It should be clear that my

critique here is not issued as a call for a

revolutionary feminism, which would be

merely glib. For we know only too well

why gendered antagonism on the model

of class antagonism is difficult if not

impossible to sustain: women are implicated with men in heterosexual relations

and in kinship structures (my father

was a man, as a character in Elizabeth

Gaskells novel Cranford observes [1851]),

and hence complicit with existing social

arrangements. The sex wars have always

been reductive as an explanation of

OCTOBER 10, 2015

vol l no 41

EPW

Economic & Political Weekly

PERSPECTIVES

what feminism stands for. And feminists, all too aware that power, domination, ownership of property and violence

are precisely the masculinist values that

underpin gender oppression and hierarchy, and confronted by the impossible

predicament of deploying these as the

means to overthrow patriarchy, have

had to rethink the goals as well as the

means of the feminism they espouse.

So, to sum up: feminism is non-teleological in its philosophy and praxis,

which is to say that its analysis is linked

to causes not outcomes; its function

is critical, rather than visionary; it is

ameliorative rather than oppositional in

its politics; and it questions established

value-systems rather than proposes alternative ones. But what might seem like

the limits of feminism and a constraint

on its politics is not necessarily so. To

bring about even one of the changes

mentioned above, however modest in

scope, would cause enough social

upheaval to be considered radical, if not

utopian in ambition.

All the same, an exploration of the

extent and kind of explicit feminist imagining, in theory and fiction, of positive

alternatives, an affirmative politics, and

constructive visions could provide

access to the realm of desire, while also

exposing its contradictions.

I identify two of the most radical

forms that such imagining has taken.

One is the vision of a separation of the

sexes resulting in a world without men,

a society exclusively of women, a Ladyland or Herland. And the other is the

destabilisation of gender, conceptualised

in terms both of an absence of gender

difference as well as of its opposite, the

proliferation of genders. The first form

of imagining identifies men as the source

of the problem and seeks to exclude

them; the second diagnoses gender as

the structural cause of the problem and

seeks to trouble the conceptual schema

of male and female. I shall return to

the implications of these ideas for

feminism, but for now I want to draw

attention to their utopian dimensions

utopian because they do not as yet exist

in pure form anywhere, although like

all utopias they have a prefigurative

dimension.

Economic & Political Weekly

EPW

OCTOBER 10, 2015

Rokeya Shekawat Hossains Sultanas

Dream is, as I said earlier, a utopian

fiction, or as the title says more simply, a

dream. Utopia is an ideal place

(eu-topia) or a no-place (ou-topia)

(Bagchi 2005: xviii); that is, it simultaneously offers an ideal and acknowledges that it is beyond reach. But insofar as

it is a place or world that has been imagined, it brings it within the scope of human imagination. What can be thought

can be realised; or to put it in less hubristic terms, what has never been thought

cannot ever be realised. The utopic

imagination represents hope, freedom,

a politics of the possible, or an immature

politics with its attendant minoritarian

and anarchic dimensions.3 What interests

me about utopia however is what a

symptomatic reading might reveal: what

reality is the utopian vision reactive to?

What are the conditions of its possibility? What limits does it operate within,

and why? What aspects of reality is it

guilty of repressing? A certain reality

is always the condition of utopia, acting

as both its constraint and its inspiration.

To recapitulate: Even if feminism has

not articulated its ends in any systematic

way in the form of a Feminist Manifestoand for good reason, as we sawit

is nevertheless not lacking in speculative explorations of questions of gender.

These have been articulated in the

generic terms of a utopia. Where this

utopia bears the specific lineaments of

science fictioneither the scientific fantasy of a world where science and technology deliver womankind (and mankind) from their condition of enslavement, or alternatively where women

acquire and use scientific knowledge to

transform the worldwe have a futurity

whose emancipatory possibilities are

uniquely feminist.

3 Sultanas Dream

I imagine that most readers are familiar

with Sultanas Dream, but here is the

obligatory synopsis nevertheless. It is not

a story driven by anything like a plot.

The author offers only a lively guided

tour through a new world, where a

charmed visitor, Sultana, is introduced

by a native, Sister Sara, to the wonders

of Ladyland as she calls the dream

vol l no 41

world. Sultana is intrigued to find that

there are no men to be seen on the

streets of the fantasy Ladyland. The men

have all been shut up indoors. In response to Sultanas protest that surely it is

womens place to be secluded since they

are naturally weak, Sara offers the

irrefutable logic that since men are dangerous like wild animals or lunatics, it is

they who must be locked upwhereas

in our world Men who do or at least are

capable of doing no end of mischief, are

let loose and the innocent women are

shut up in the zenana! Sara blames

women for their own incarceration:

You have neglected the duty you owe to

yourselves, and you have lost your natural rights by shutting your eyes to your

own interests (Hossain 1988: 9).

Sister Sara moves easily between the

old world and the new to draw comparisons, for the changes in her own country

had happened only 30 years before with

the succession of their queen. The

young queen introduced compulsory

education for all the women and banned

marriage for them before the age of 21.

As a result there were women scientists

in her realm who were able to conduct

marvellous researches; and they invent

machines to draw water from the atmosphere and store the heat of the sun.

When the enemy attacked the country,

the men went out to fight and got killed,

while the women were able to beat back

the enemy with the help of their heat

machines. The queen took over the reins

of government and had the men retreat

into seclusion, where they have remained ever since. Under her enlightened

rule, the land thrives. We make nature

yield as much as she can, Sara explains,

so that there is electricity and aerial

transport, clean streets and lush gardens

in the land; and pleasurable labour,

plenty of leisure, no crime and no disease. Sultana meets the Queen who

repeats Saras encomiums on scientific

education: We dive deep into the ocean

of knowledge and try to find out the precious gems that Nature has kept in store

for us (Hossain 1988: 17). After she has

visited all the places of learning in Ladylandthe universities, the laboratories

and the observatoriesSultana wakes up

from her dream and the story ends there.

41

PERSPECTIVES

Sultanas Dream is rightly admired

for its charming conceit of a reversal of

gendered roles which places women in

government and visible in public space

(streets, gardens), and men in powerless

roles and invisible in domestic spaces

(kitchens, the mardana). The consequences are entirely beneficial; and there

is poetic justice in the fate that men

suffer as it is their own self-destructive

aggression that brings them to defeat.

Women, given the opportunity, use their

political and military power wisely and

with restraint, and they put their scientific knowledge to the best possible use,

for development and environmental

purposes. Rokeyas expressed admiration for Gullivers Travels suggests that

Swifts satirical fantasy may have given

her the idea of constructing an imaginary, alternative world and exploiting its

potential for the play of ideas. Sultanas

Dream is bound to remind us of Alice in

Wonderland too (although I have not

been able to find out if Rokeya had actually read Lewis Carrolls classic story).

The parallels between the two works lie

in the similar dream/fantasy plot of a

young girl driven by curiosity to explore

strange worlds; the openness and wonder with which in each case she receives

an initiation into novel experiences and

a continuous education in ideas; and the

internal logic with which these worlds

cohere. Other writers too have developed the premise of separate worlds in

their novels, notably Charlotte Perkins

Gilman in Herland (1915), published only

a few years later.

Resemblance to Hind Swaraj

But Sultanas Dream bears as well an

unexpected resemblance to yet another

literary oddity from the Indian subcontinent almost contemporary with it:

Gandhis Hind Swaraj (1909). The dialogic form of both texts, between a leading guide and an interlocutor, is strikingly similar. When Gandhi in the persona of the Editor corrects the reader,

who gives the credit for Britains conquest of India to its superior civilisation,

by pointing out: The English have not

taken India; we have given it to them.

They are not in India because of their

strength, but because we keep them

42

(Gandhi 1997: 39), he places both blame

and agency on the conquered, in

exactly the same way as Rokeya, in

the persona of Sister Sara, chides the

women of Bengal for losing their

freedom to men. But just as striking

are the opposed positions the authors

take on the question of science and

technology. Where Gandhi famously

rejects everything about western modernity including Enlightenment rationalism

and the advances of science, Rokeya

seeks the clear light of reason and the

benefits of technology in establishing a

good society.

Rokeya wrote that when her husband

finished reading her story, he immediately commented A terrible revenge!

(cited in Jahan 1998: 2). It is of course

mens disappearance into the zenana

that will strike readers as the masterstroke of the narrative. But although

much has been made of the revenge

motif, Sultanas Dream cannot be read

as primarily an attack on the male sex.

Rokeya could not have been blind to the

ideological implications of an idealised

female ruler maintaining segregation

and retaining the sexual division of

labour while merely inverting it. The

text is noticeably reticent about the politics of the reverse enslavement of men. It

displays a similar reticencesurely a

sign of discomfortabout womens

recourse to military might and bloodshed in defence of their land (even if the

weapons be advanced scientific inventions). Gandhi on the other hand mocks

the fiery nationalistic reader who would

keep English rule, without the Englishman. You want the tigers nature, but not

the tiger. As for himself, he makes it

clear that this is not the Swaraj that I

want (Jahan 1998: 28). Rokeya however

is pushed to acknowledge that a female

regime would be possible only if men

were overthrown and kept under control; and that for this to happen, force

would be required. The necessity of

force as an aspect of the stateeven if

Ladyland does away with police and

magistratesis obviously contrary to the

philosophy of Hind Swaraj. The difficult

conditions of possibility of a Ladyland

cannot be wished away, but Sultanas

Dream does not celebrate them in a

triumphalist spirit. The contradictions

underlying feminisms futures are made

transparent in Sultanas Dream.

Rokeya seems to accept without question that there are essential female

values such as pacifism, the cultivation

of nature, harmonious social coexistence,

and avoidance of conflict which will

inform a female-dominated society. More

questionable still, especially to readers

today (although her defenders point out

that she wrote before the two world

wars and the atom bomb), is her unquestioned faith in the beneficial value of

technological advances and scientific

discoveries. Humankinds conquest of

nature is embraced as unadulterated

good. Sultanas wonderment at the

absence of mosquitoes and at the

well-run kitchens in Ladyland is typical

of the navely awed responses of many

in the underdeveloped world to the

condition of Western societies with their

shining marvels of gadgetry and functioning order.

Even weapons of war are used with

restraint for good ends in Ladyland

(they were not even invented primarily

for killing), and they function mainly as

deterrent. Barnita Bagchi stresses that

the driving force behind the success of

the utopian feminist country of Ladyland is womens education, and science,

technology and virtue work together in

perfect harmony. Ladyland, she concludes, embodies the triumph of the

virtuous, enquiring, scientific, enlightened and welfare-oriented spirit in

women. (Bagchi 2005: xii, xiii) It is also

worth noting that the education of girls

at the time (as even now) tended to

stress the useful domestic skills and

soft subjects rather than the hard

sciences; so Rokeya is also making the

point that women must acquire the same

knowledge as men, and are perfectly

capable of acquiring mastery of the

sciences. Knowledge is not only power in

Ladyland, but also enlightenment. The

faith displayed here in all innocence,

both in the capacity of technology to

achieve a good society and in womens

differentethical, purposiveuse of

scientific knowledgehave understandably been subjected to questioning. I

want now to contextualise this aspect

OCTOBER 10, 2015

vol l no 41

EPW

Economic & Political Weekly

PERSPECTIVES

of Rokeyas storyits techno-scientific

utopianismwithin a broader feminist

theoretical frame.

4 Conceptualising Alternatives

It is usual to identify three distinctive

feminist modes of conceptualising alternative social relations or political structures, namely, the political-liberal, the

ethical-radical, and the sexual-technoscientific. I am sure there is no need to

rehearse each of these in any detail since

this is a widely used classification of

feminist thought and praxis.

The first, political-liberal feminism, is

usually traced back to the French Revolution which provided the language of

equality to women, however inadvertently (Scott 1996). The demand for

political equality for women, starting

with the right to vote and moving quickly on to other kinds of parityequal pay

at the workplace, equal opportunity for

education and entry into careers, childcare and maternity benefits, wages for

housework and the kind. The feminist

campaign against violence is also

couched in the language of rights, more

recently in human rights language,

where even culturally and socially sanctioned violence is deemed to constitute

an offence against womens human

rights and comes into conflict with

them. Although this kind of juridical

equality has by and large been conceded

to women worldwide by national constitutions and through universal United

Nations mandates and conventions, it

constitutes its own limits. Quite apart

from the distance we can track between

formal equality and actually obtaining

conditions of inequality in many contextsand the difficulty of enforcing

equal rights for women or other disadvantaged constituencieseven as an

achieved goal it has to acknowledge a

ceiling. More recently, influential critiques of liberal feminism have originated from feminist and other intellectuals adopting and advocating culturally

other perspectives.4

The differing emphases of womens

demands are sometimes envisaged as

constituting evolutionary stages or

phases of the feminist movement. Thus,

Juliet Mitchell (1984) sees the historical

Economic & Political Weekly

EPW

OCTOBER 10, 2015

trajectory of second-wave Western feminism in the following terms:

The first stage of our movement was directed to putting right the wrongs of women, the

second to an emphasis on the values, the importance of the qualities of womanhood and

femininitypeace, caring, nurturance.

The second phase that I have identified

by the label radicalethical, is a move

away from liberal equality and the struggle for rights/justice, now perceived not

just as insufficient but as actually complicit with masculinist values. The major

move towards embracing an alterity

coded as feminine involves simultaneously envisaging social relations and

political structures in a radically different mode; essential female attributes of

care, nurture, cooperation, pacifism

and the like displace conflict, competition, instrumental reason now deemed

essentially male in origin and as ideology. Rokeyas feminism is both liberal

political in urging social reform, education and political participation for

women, as well as ethicalradical in

advocating a separate and different

female world.

More radical still is a relatively recent

development in feminismthe questioning of the sex-gender system itself. It

draws upon the post-structuralist deconstruction of binary structures with

which the name of Jacques Derrida is

associated and upon Michel Foucaults

studies in the History of Sexuality. Drawing on their work, French feminist theorists like Monique Wittig and Luce Irigaray have sought to unground sexual

identities. If the opposition manwoman

has been built on the ostensible biological difference between the sexes and has

in turn supported the sexual division of

labour, then this structure itself would

have to be demystified in order to dismantle the system. Why two sexes? Why

not a proliferation of sexual identities on

a much broader spectrum? If sexual difference is the ground of womens oppressionconsigned to child-bearing and

maternal functions, and perceived as

the object of sexual violencethen the

removal of sexual difference alone can

liberate them. The refusal of biology as

destinyprogrammatically argued in

Simone de Beauvoirs Second Sex (1951)

vol l no 41

has of course long constituted one of

feminisms stands. Donna Haraway

expressed the utopian dream of the hope

for a monstrous world without gender

(1985: 181). Judith Butlers argument

about the performativity of gender is

intended to render it flexible and open to

transformation. In the view of feminists,

Butler explains, gender is something

that should be overthrown, eliminated,

or rendered fatally ambiguous precisely

because it is always a sign of subordination for women (1999: xiii). Genderlessness through the abolition of gender is a

feminist future, arguably analogous to

Marxisms goal of achieving a classless

society by eradicating class.

While much of the impetus for this

theoretical thinking has come from the

lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender (LGBT)

movement in recent years, and, in turn,

informed it, the dissolution of gender

identities and of the sexual difference

itself has been an aspect of the utopian

imagination for much longer.5 In Sultanas

Dream, the very ease with which the

reversal of gender roles is brought about

is an indication of its performative

condition. To her surprise Sultana is

viewed in Ladyland as mannish in her

appearance. Sister Sara enlightens her

it is because she is so shy that she resembles the new men in her country.

Sultanas shyness is of course the result

of her being a purdanashin woman in

her own society, one unaccustomed to

being out on the streets without her

veilin contrast to the fearlessness and

confidence with which women in Ladyland move around. Here it is the men

who are shy and reclusive.

I have connected the sexual radicalism

to techno-scientific developments, but it

must be noted that the connection does

not explicitly figure in either French

feminist thought or Judith Butlers work.

Nor has it been prominent in the contemporary LGBT movement. Rokeya herself is vague about the sexual order of

Ladyland; the queen has a little daughter, although we learn that childcare is

left to the men in their domestic roles.

Presumably men play their traditional

role in sexual reproduction, but there

is no explicit mention of marriage or

the usual forms of heterosexual union. It

43

PERSPECTIVES

is of course their superiority in scientific

and technological knowhow that gives

women the upper hand in Ladyland and

inverts the power structure, but Rokeya

does not stretch her imagination so far

as to envisage the biological order itself

being disturbed by scientific advances in

the field. This had to await discoveries

and innovations that came later in the

20th century.

5 Techno-Scientific Utopias?

The earliest of the feminist works which

seized on the potential for womens liberation through scientific advances in

biotechnology and cybernetics was

Shulamith Firestones The Dialectic of

Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution,

published in 1970. Firestone called for a

feminist revolution whose goal would

be not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself:

genital differences between human

beings would no longer matter culturally

(p 11). Her vision was futuristic, but it

grew from a Marxist consciousness of

history. Drawing on Engels, she maintained that only the proper identification of the origins of antagonism could

provide the means to end it. The source

of womens oppression lies in biology,

specifically the sexual uniqueness that

makes women the sole reproducers of

the species. Child-bearing and childrearing are physically constraining and

painful for women, not merely socially

demanding roles.

But if Firestone concedes female biological oppression, she also argues her

way out of it with the confidence that

modern scientific progress will make it

possible to conquer Nature, providing

deliverance from the primitive and

oppressed animal life that mankind

lives. Her scenario of the future extends the possibilities of a present in

which humanity has begun to transcend Nature (p 10). She is filled with

optimism about the potential of the

20th century scientific revolution to

bring about the emancipation of women

and workers:

A feminist revolution could be the decisive factor in establishing a new ecological

balance: attention drawn to the popula

tion explosion, a shifting of emphasis from

44

r eproduction to contraception and demands

for the full development of artificial reproduction would provide an alternative to the

oppressions of the biological family; cybernation, by changing mans relationship to

work and wages, by transforming activity

from work to play (activity done for its

own sake), would allow for a total redefinition of the economy, including the family unit in its economic capacity. The double

curse, that man should till the soil by the

sweat of his brow, and that woman should

bear in pain and travail, would be lifted

through technology to make humane living,

for the first time, a possibility (p 184).

Juliet Mitchell (1971) paraphrases

these ideas in terms of Firestones radical feminism:

Radical feminism, the revolution for the

release of the oppressed majority of the

world, would liberate test-tube babies, babyfarms, big-brother control, from their confinement within the horrors of brave new

world and 1984, and guarantee that their

humane application would finally free mankind from the trap of painful biology. Thus

culture would at last overcome nature and

the ultimate revolution would be achieved.

I have quoted at some length from The

Dialectic of Sex and Mitchells gloss on

the book in order to show the extent of

faith that a certain strand of feminist

thought has invested in biotechnological

means of liberating women from their

biologically-produced oppression.

In the late 1980s Donna Haraways

Cyborg Manifesto would revisit the

by then largely forgotten and aban

doned agenda of Firestones work. The

cyborg is our ontology, Haraway anno

unced, using the present tense in an

anticipatory way (1991: 150). We are

c yborgs, she affirmed, creatures simultaneously animal and machine, who

populate worlds ambiguously natural

and crafted (p 149). She takes recourse

to feminist science fiction to read in

these texts the quite different political

possibilities and limits from those proposed by the mundane fiction of Man

and Woman (p 180). The feminist position in these postmodern times would

be to face radical scientific transformations of the biological, and by extension

the social world, squarely. By taking

responsibility for the social relations of

science and technology and refusing

an anti-science metaphysics, a demono

logy of technology (p 181), women

would be enabled to transcend gender.

What aligns Haraways work with

Subscribe to the Print edition

What do you get with

a Print subscription?

50 issues delivered to your door every year

All special and review issues

Access to Archives of the past two years

Web Exclusives

And a host of other features on www.epw.in

To subscribe, visit: www.epw.in/subscribe.html

Attractive rates available for students, individuals and institutions.

Postal address: Economic and Political Weekly,

320-321, A to Z Industrial Estate, GK Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai 400 013, India.

Tel: +91-22-40638282 | Email: circulation@epw.in

OCTOBER 10, 2015 vol l no 41 EPW Economic & Political Weekly

PERSPECTIVES

Firestones, despite considerable differences between them, is their shared

faith in overcoming the gendered condition through the opportunities afforded

by the biotechnological revolution.

However, what is not clear from Firestones position (or for that matter Haraways) is what role women in general or

the feminist movement in particular

would play in bringing about this development. Twentieth century advances in

contraception, the birth control pill in

particular, have undeniably produced a

transformation in heterosexual relations

and in the female condition itself for

which the term liberation can be used

(even if ironically). As more forms of

reproduction through artificial insemination, artificial wombs, the freezing of

embryos, test-tube babies, cloning and

the like proliferate, the relationship of

the sexes is bound to change definitively.

But it is not women, women scientists, or

feminist demands that are driving these

changes, or not primarily. And we would

be right to ask how much of an unmixed

good the advances themselves represent. There is no doubt that these, like

labour-saving machinery and the condition of women in the workplace, have to

be articulated with capitalist developments in production and technology.

Not that either Firestone or Haraway

was blind to modern science and technologys connections with capitalism, in

both production and consumption. As

self-identified and recognisable socialist

feminists they worked with (although

not within) Marxist categories. But neither of them gets into the details of how

a feminist praxis that would overturn

capitalist domination and take over its

instruments will be staged. Indeed Haraway does not propose a revolutionary

praxis at all; her postmodern position

implies faith in the more diffuse expression of subversion and ambivalence. It is

Rokeya who envisages womens capture

of the state as well as the takeover of the

scientific establishment by women scientists as the implicit preconditions of

science and technology being put to progressive uses. True, in Sultanas Dream

these ends are not directly in the service

of womens biological and physical emancipation, being broadly environmental

Economic & Political Weekly

EPW

OCTOBER 10, 2015

and developmental. However between

them the woman writer from early 20th

century colonial India and the feminist

theorists from late-capitalist United

States cover complementary aspects of a

feminist utopia.

I am conscious that my essay has left

several pressing questions unanswered

and unattempted. There is the politics of

utopia itself, a much-debated issue that I

have not touched upon.6 There is also

the controversial content of this utopia,

the imaginary of a brave new world (it is

not for nothing that the majority of

visions of a scientifically advanced society are dystopic). Arguably too, the goal

of social emancipation achieved through

the radical destabilisation of gender systems requires much greater thought.7

But this is precisely the point. Technoscientific utopias that envisage social

well-being as nothing less than the amelioration of the human condition itself,

challenge us to interrogate their premises

and their reasoning. Rokeyas dream

repays consideration today as much as it

did over one hundred years agoeven

though it may not be responsive to our

immediate fire-fighting urgenciesif

only because it pushes us to consider

what it is we want.

Notes

1

5

6

The first was the shooting of a schoolgirl Malala

Yousafzai by the Taliban in the Swat District in

Afghanistan in October 2012, and the second

the gang rape and killing of a young woman,

Jyoti Singh Pandey, on a bus in New Delhi,

India in December 2012.

Instead we have the term empowerment to refer

to a kind of muscle-building, self-improvement

exercise for women.

The last phrase is Leela Gandhis Affective Communities (2006). See especially Chapter 7,

pp 177ff.

From perceiving the limits of equality politics

such critiques have proceeded to question the

hegemony of claims made in the name of its

universality. Ethnographies like Saba Mahmoods Politics of Piety, for instance, have invoked strong cultural relativist arguments (problematically, to my mind) to recognise and legitimise pious Egyptian Muslim (Salafa) womens submissive religiosity in order to challenge

liberal feminism, and have succeeded in considerably destabilising its complacency.

For an interesting discussion, see Noah Berlatsky

(2013).

Frederic Jamesons The Politics of Utopia, is

among the most well-known recent reflections

on the subject.

Cf Angelo Brieussel: to focus on the utopian

ideal of a genderless society might well be

counterproductive to the expansion of freedom

for gendered beings. Attempts at the obliteration of difference throughout history have

vol l no 41

proven to be some of the most violent impositions on the collective human body and psyche,

and which have been distinctly gendered. In

other words, a genderless society might not

even be imaginable, let alone achievable or

desirable, at this stage in Western Lifeworlds.

References

Bagchi, Barnita (2005): Introduction to Rokeya

Sakhawat Hossain, Sultanas Dream and Padmarag, translated and with an Introduction by

Barnita Bagchi, New Delhi: Penguin Books India.

Berlatsky, Noah Berlatsky (2013): Imagine Theres

No Gender: The Long History of Feminist Utopian Literature, The Atlantic, 15 April, online

at http://www.theatlantic.com/sexes/archive/

2013/04/imagine-theres-no-gender-the-longhistory-of-feminist-utopian-literature/274993/

Brieussel, Angelo (nd): Would It be Possible to

Have a Aociety without Gender? If So, What

Might It Look Like?: http://www.academia.

edu/2216281/Would_it_be_possible_to_have_

a_society_without_gender_If_so_what_might

_it_look_like

Butler, Judith (1999): Gender Trouble: Feminism

and the Subversion of Identity, New York:

Routledge Press, 10th anniversary edition.

Faludi, Susan (1991): Backlash: The Undeclared War

against American Women, New York: Crown.

Firestone, Shulamith (1970): The Dialectic of Sex:

The Case for Feminist Revolution, New York:

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Gandhi, Leela (2006): Affective Communities: Anticolonial Thought, Fin-de-Sicle Radicalism and

the Politics of Friendship, Durham: Duke University Press.

Gandhi, M K (1997): Hind Swaraj and Other Writings, edited by Anthony J Parel, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Haraway, Donna (1991): The Cyborg Manifesto,

Socialist Review, 1985, revised and reprinted in

Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The

Reinvention of Nature, New York: Routledge,

pp 14981

Hossain, Rokeya Sakhawat (1988): Sultanas

Dream: A Feminist Utopia and Selections from

the Secluded Ones, edited and introduced by

Roushan Jahan, New York: The Feminist Press.

Jahan, Roushan (1988): Sultanas Dream: Purdah

Reversed and Rokeya: An Introduction to her

Life, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, Sultanas

Dream: A Feminist Utopia and Selections from

the Secluded Ones, edited and introduced by

Roushan Jahan, New York: The Feminist Press.

Jameson, Frederic (2004): The Politics of Utopia,

New Left Review, 25, JanuaryFebruary,

pp 3554.

Mahmood, Saba (2004): The Politics of Piety: The

Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

McRobbie, Angela (2004). Post Feminism and

Popular Culture, Feminist Media Studies, 4, 3,

pp 25564.

Mitchell, Juliet (1971): Womens Estate, London:

Penguin. Excerpt online at: https://www.

marxists.org/subject/women/authors/mitchell-juliet/longest-revolution.htm

(1984): Women: The Longest Revolution: Essays

on Feminism, Literature and Psychoanalysis,

London: Virago.

Rosin, Hanna (2010): The End of Men, The Atlantic,

July/August; online at: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2010/07/the-endof-men/308135/

Scott, Joan (1996): Only Paradoxes to Offer: French

Feminists and the Rights of Man, Cambridge,

Mass: Harvard University Press.

Walby, Sylvia (2011): The Future of Feminism,

London: Polity.

45

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Limitations of Social Media Feminism: No Space of Our OwnD'EverandThe Limitations of Social Media Feminism: No Space of Our OwnPas encore d'évaluation

- Afro SuperhAfro-superheroes: Prepossessing The Futureeroes Prepossessing The FutureDocument5 pagesAfro SuperhAfro-superheroes: Prepossessing The Futureeroes Prepossessing The FutureAlan MullerPas encore d'évaluation

- (Gender in A Global - Local World) Jacqueline Leckie-Development in An Insecure and Gendered World - The Relevance of The Millennium Goals-Ashgate (2009) PDFDocument267 pages(Gender in A Global - Local World) Jacqueline Leckie-Development in An Insecure and Gendered World - The Relevance of The Millennium Goals-Ashgate (2009) PDFDamla YazarPas encore d'évaluation

- An Eco Feminist Study of Alice Walker The Color PurpleDocument6 pagesAn Eco Feminist Study of Alice Walker The Color PurpleAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- The "Demonic" in Ibsen's in The Wild DuckDocument9 pagesThe "Demonic" in Ibsen's in The Wild DuckfitranaamaliahPas encore d'évaluation

- Feminism: Broad Streams of FeminismDocument4 pagesFeminism: Broad Streams of FeminismDexin JoyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Format. Hum-Women in Science Fiction and FeminismDocument8 pagesFormat. Hum-Women in Science Fiction and FeminismImpact JournalsPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Studies - Women and Madness in Film and LiteratureDocument10 pagesGender Studies - Women and Madness in Film and LiteratureLu_fibonacciPas encore d'évaluation

- Synopsis Chetna NegiDocument19 pagesSynopsis Chetna NegiChetna NegiPas encore d'évaluation

- She-who-must-be-obeyed'Anthropology and PDFDocument19 pagesShe-who-must-be-obeyed'Anthropology and PDFmasohaPas encore d'évaluation

- Feminist Criticism A Revolution of Thought A Study On Showalters Feminist Criticism in The Wilderness MR Hayel Mohammed Ahmed AlhajjDocument6 pagesFeminist Criticism A Revolution of Thought A Study On Showalters Feminist Criticism in The Wilderness MR Hayel Mohammed Ahmed Alhajjκου σηικ100% (1)

- Briggs Interview CommunicabilityDocument30 pagesBriggs Interview CommunicabilityTHAYSE FIGUEIRA GUIMARAESPas encore d'évaluation

- Representation of Women in Hijazi Proverbs FinalDocument17 pagesRepresentation of Women in Hijazi Proverbs Finalجوهره سلطان100% (1)

- Science Fiction Studies Vol 19 Volume InformationDocument5 pagesScience Fiction Studies Vol 19 Volume InformationAlquirPas encore d'évaluation

- Molly Millions As The Absolute "Other": A Futile Rewiring of The Feminine Self in NeuromancerDocument4 pagesMolly Millions As The Absolute "Other": A Futile Rewiring of The Feminine Self in NeuromancerJustin Ian ChiaPas encore d'évaluation

- An Ecofeministic Reading of Leslie Marmon Silko's Select Short StoriesDocument9 pagesAn Ecofeministic Reading of Leslie Marmon Silko's Select Short StoriesMohammedMohsinPas encore d'évaluation

- C. Delphy - The Invention of French FeminismDocument33 pagesC. Delphy - The Invention of French FeminismAne A Ze TxispaPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Communication Inquiry-2008-Dhaenens-335-47 PDFDocument13 pagesJournal of Communication Inquiry-2008-Dhaenens-335-47 PDFkakka kikkarePas encore d'évaluation

- 11 American Gothic HandoutDocument5 pages11 American Gothic HandoutDaniraKucevicPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sex Which Is Not One Luce IrigarayDocument2 pagesThe Sex Which Is Not One Luce IrigaraySAC DUPas encore d'évaluation

- The Male GazeDocument14 pagesThe Male GazeMarthe BwirirePas encore d'évaluation

- Inheritance After ApocalypseDocument13 pagesInheritance After ApocalypseGonzalo_Hernàndez_BaptistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Porter, "Aimé Césaire's Reworking of Shakespeare Anticolonialist Discourse in Une Tempête"Document23 pagesPorter, "Aimé Césaire's Reworking of Shakespeare Anticolonialist Discourse in Une Tempête"MeredithPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes Epistemologies of The SouthDocument7 pagesNotes Epistemologies of The SouthNinniKarjalainenPas encore d'évaluation

- Juda Bennett - Toni Morrison and The Burden of The Passing NarrativeDocument14 pagesJuda Bennett - Toni Morrison and The Burden of The Passing NarrativeIncógnitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Resistance Against Marginalization of Afro-American Women in Alice Walker's The Color PurpleDocument9 pagesResistance Against Marginalization of Afro-American Women in Alice Walker's The Color PurpleIJELS Research JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Julia Desire of LanguageDocument10 pagesJulia Desire of Languagesarmahpuja9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chinese-American Cross-Cultural Communication Through Contemporary American Fiction: The Joy Luck Club As An Illustrative ExampleDocument14 pagesChinese-American Cross-Cultural Communication Through Contemporary American Fiction: The Joy Luck Club As An Illustrative Exampleazam.mukhiddinovPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender and French CinemaDocument309 pagesGender and French CinemaAndrea Saavedra100% (1)

- Ever After Postmemory Fairy Tales and The Body in Second Generation Memoirs by Jewish WomenDocument18 pagesEver After Postmemory Fairy Tales and The Body in Second Generation Memoirs by Jewish WomenHouda BoursPas encore d'évaluation

- Silas Morgan - Lacan, Language and The Self - A Postmodern Vision of SpiritualityDocument7 pagesSilas Morgan - Lacan, Language and The Self - A Postmodern Vision of SpiritualitytanuwidjojoPas encore d'évaluation

- Prof SAYNI M1 2022-23 IntertextualityDocument13 pagesProf SAYNI M1 2022-23 IntertextualityHouphouetlv YaoPas encore d'évaluation

- J 0201247579Document5 pagesJ 0201247579Lini DasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Socio-Cultural Explorations in Shashi Deshpande's "The Dark Holds No Terror"Document7 pagesSocio-Cultural Explorations in Shashi Deshpande's "The Dark Holds No Terror"Anonymous CwJeBCAXpPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Performativity and The Complexities of AndrogynyDocument9 pagesGender Performativity and The Complexities of AndrogynyDouglas HudsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Haraway - A Cyborg Manifesto - ComentarioDocument9 pagesHaraway - A Cyborg Manifesto - ComentarioGabrielaRmerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fin de SiecleDocument25 pagesThe Fin de SiecleBob CollisPas encore d'évaluation

- Costumes of The Mind. Transvestism As Metaphor in Modern LiteratureDocument27 pagesCostumes of The Mind. Transvestism As Metaphor in Modern LiteratureDiego Mayoral MartínPas encore d'évaluation

- Bridging Narratology andDocument80 pagesBridging Narratology andAndreas AlexiouPas encore d'évaluation

- 4674-Telling Feminist StoriesDocument26 pages4674-Telling Feminist StoriesCee Kay100% (1)

- What Is RepresentationDocument3 pagesWhat Is RepresentationrobynmdPas encore d'évaluation

- EDUC3013 Essay 2Document7 pagesEDUC3013 Essay 2Zoie SuttonPas encore d'évaluation

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: A Critical Study: ThesisDocument185 pagesGayatri Chakravorty Spivak: A Critical Study: ThesisJulia BanerjeePas encore d'évaluation

- The Post-Modern Fracturing of Narrative Unity Discontinuity and Irony What Is Post-Modernism?Document2 pagesThe Post-Modern Fracturing of Narrative Unity Discontinuity and Irony What Is Post-Modernism?hazelakiko torresPas encore d'évaluation

- Modernist LiteratureDocument10 pagesModernist LiteratureGabriela PaunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender, Genre, and Myth in Thelma and Louise.Document19 pagesGender, Genre, and Myth in Thelma and Louise.ushiyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Rahul Kumar Singh Gen 740 Ca1 42000223Document11 pagesRahul Kumar Singh Gen 740 Ca1 42000223Rahul Kumar SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Postfeminism and The Girls' Game Movement: Destined For FailureDocument26 pagesPostfeminism and The Girls' Game Movement: Destined For FailureRenee Powers100% (1)

- De Groot Historical NovelDocument20 pagesDe Groot Historical NovelIshmael G100% (2)

- Begum RokeyaDocument2 pagesBegum Rokeyaadyman1100% (1)

- Mel GibsonDocument10 pagesMel GibsonfranjuranPas encore d'évaluation

- Myth of QuestfDocument9 pagesMyth of QuestfshadowhuePas encore d'évaluation

- A Short History of Utopian Studies.2009Document12 pagesA Short History of Utopian Studies.2009Dobriša CesarićPas encore d'évaluation

- Charlotte Hooper Masculinities IR and The Gender VariableDocument18 pagesCharlotte Hooper Masculinities IR and The Gender VariableMahvish Ahmad100% (1)

- 126-131 Sadiya Nair SDocument6 pages126-131 Sadiya Nair SEhsanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rakshanda JalilDocument5 pagesRakshanda JalilSIMRAN MISHRAPas encore d'évaluation

- Gonzalez Elena Critical AnalysisDocument5 pagesGonzalez Elena Critical Analysisapi-535201604Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gothic-Fantastic Lectures OutlineDocument2 pagesGothic-Fantastic Lectures OutlineAnonymous v5EC9XQ30Pas encore d'évaluation

- Simulation and Simulacrum As Ways of Being in The WorldDocument9 pagesSimulation and Simulacrum As Ways of Being in The WorldPilar MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Blah 123Document1 pageBlah 123Sumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Tiffany Case AnalysisDocument3 pagesTiffany Case AnalysisSumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Blah 12Document1 pageBlah 12Sumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Blah 12Document1 pageBlah 12Sumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Blah 1Document1 pageBlah 1Sumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Kuch Bhi 2Document1 pageKuch Bhi 2Sumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Kuch BhiDocument1 pageKuch BhiSumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Is There An Indian Way of Thinking An Informal EssayDocument19 pagesIs There An Indian Way of Thinking An Informal EssayArusree Mohanty ChhayaPas encore d'évaluation

- I Am No Virgin, Yet I Never Made LoveDocument2 pagesI Am No Virgin, Yet I Never Made LoveSumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Zerodha Stock Market PDFDocument108 pagesZerodha Stock Market PDFAnshu GauravPas encore d'évaluation

- Eula Microsoft Visual StudioDocument3 pagesEula Microsoft Visual StudioqwwerttyyPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergence of and Development SociologyDocument54 pagesEmergence of and Development SociologySumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample 1ADocument1 pageSample 1ASumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample ASDDocument1 pageSample ASDSumeet SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Indian Students Are Disliked in USADocument1 pageWhy Indian Students Are Disliked in USASagar MohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Indian Students Are Disliked in USADocument1 pageWhy Indian Students Are Disliked in USASagar MohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Exception Report Document CodesDocument33 pagesException Report Document CodesForeclosure Fraud100% (1)

- Introduction Business EthicsDocument24 pagesIntroduction Business EthicsSumit Kumar100% (1)

- AMCTender DocumentDocument135 pagesAMCTender DocumentsdattaPas encore d'évaluation

- Write A Letter To Your Friend Describing Your Sister's Birthday Party Which You Had Organized. You May Us The Following Ideas To Help YouDocument2 pagesWrite A Letter To Your Friend Describing Your Sister's Birthday Party Which You Had Organized. You May Us The Following Ideas To Help YouQhairunisa HinsanPas encore d'évaluation

- Ang vs. TeodoroDocument2 pagesAng vs. TeodoroDonna DumaliangPas encore d'évaluation

- Position Paper in Purposive CommunicationDocument2 pagesPosition Paper in Purposive CommunicationKhynjoan AlfilerPas encore d'évaluation

- Cruz v. IAC DigestDocument1 pageCruz v. IAC DigestFrancis GuinooPas encore d'évaluation

- Combinepdf PDFDocument487 pagesCombinepdf PDFpiyushPas encore d'évaluation

- Lancesoft Offer LetterDocument5 pagesLancesoft Offer LetterYogendraPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Punishment For Environmental DamageDocument25 pagesCriminal Punishment For Environmental DamagePatricio Castillo DoiziPas encore d'évaluation

- Turriff& District Community Council Incorporating Turriff Town Pride GroupDocument7 pagesTurriff& District Community Council Incorporating Turriff Town Pride GroupMy TurriffPas encore d'évaluation

- Valuation of Fixed Assets in Special CasesDocument7 pagesValuation of Fixed Assets in Special CasesPinky MehtaPas encore d'évaluation

- Split Payment Cervantes, Edlene B. 01-04-11Document1 pageSplit Payment Cervantes, Edlene B. 01-04-11Ervin Joseph Bato CervantesPas encore d'évaluation

- Bus Ticket Invoice 1465625515Document2 pagesBus Ticket Invoice 1465625515Manthan MarvaniyaPas encore d'évaluation

- KW Branding Identity GuideDocument44 pagesKW Branding Identity GuidedcsudweeksPas encore d'évaluation

- BACK EmfDocument12 pagesBACK Emfarshad_rcciitPas encore d'évaluation

- BCI4001 Cyber Forensics and Investigation: LTPJC 3 0 0 4 4Document4 pagesBCI4001 Cyber Forensics and Investigation: LTPJC 3 0 0 4 4raj anaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tri-City Times: New Manager Ready To Embrace ChallengesDocument20 pagesTri-City Times: New Manager Ready To Embrace ChallengesWoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Network: Brazil The PhilippinesDocument1 pageGlobal Network: Brazil The Philippinesmayuresh1101Pas encore d'évaluation

- Admixtures For Concrete, Mortar and Grout ÐDocument12 pagesAdmixtures For Concrete, Mortar and Grout Ðhz135874Pas encore d'évaluation

- FortiClient EMSDocument54 pagesFortiClient EMSada ymeriPas encore d'évaluation

- Arbitration ClauseDocument5 pagesArbitration ClauseAnupama MahajanPas encore d'évaluation

- CHESS TECHNICAL GUIDELINES FOR PALARO 2023 FinalDocument14 pagesCHESS TECHNICAL GUIDELINES FOR PALARO 2023 FinalKaren Joy Dela Torre100% (1)

- G.O.Ms - No.1140 Dated 02.12Document1 pageG.O.Ms - No.1140 Dated 02.12bksridhar1968100% (1)

- Thomas W. McArthur v. Clark Clifford, Secretary of Defense, 393 U.S. 1002 (1969)Document2 pagesThomas W. McArthur v. Clark Clifford, Secretary of Defense, 393 U.S. 1002 (1969)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Grande V AntonioDocument17 pagesGrande V Antoniochristopher1julian1aPas encore d'évaluation

- Subercaseaux, GuillermoDocument416 pagesSubercaseaux, GuillermoMarco Cabesour Hernandez RomanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Carta de Jamaica 1815. Simon BolivarDocument16 pagesThe Carta de Jamaica 1815. Simon BolivarOmarPas encore d'évaluation

- Procedimentos Técnicos PDFDocument29 pagesProcedimentos Técnicos PDFMárcio Henrique Vieira AmaroPas encore d'évaluation

- FW 8 BenDocument1 pageFW 8 BenMario Vargas HerreraPas encore d'évaluation