Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Caluzor V Llanillo

Transféré par

fcnrrs0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

295 vues1 pageTenancy relationship; Agrarian reform law

Titre original

Caluzor v Llanillo

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentTenancy relationship; Agrarian reform law

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

295 vues1 pageCaluzor V Llanillo

Transféré par

fcnrrsTenancy relationship; Agrarian reform law

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 1

Caluzor v.

Llanillo, Moldex Realty

Facts:

Petitioner Romeo Caluzor alleges that Lorenzo Llanillo took him as

a tenant, giving him (Caluzor) a sketch of the the land he will be

cultivating. Even after the death of Lorenzo, Caluzor continued

giving Lorenzos share to his overseer, Martin Ricardo. In 1990,

Deogracias Llanillo, son of Lorenzo, offered to pay Caluzor P17,000

per hectare of the cultivated land in exchange for turning his

(Caluzors) tillage over to Deogracias. However, no payment was

made and instead, Caluzor was ejected from the land. Efforts

before the Barangay Agrarian Reform Council proved futile which

gave authority to Caluzor to file the instant case.

Before the PARAD

Petitioner prayed for the restoration of land to his possession and

prayed for the payment of disturbance compensation. On the other

hand, Deogracias denied any tenancy relationship existed between

him and Caluzor; he presented several documents, among which

are the master list of tenants and landowners, and a letter for

requesting a change in the classification of the land.

Meanwhile, DAR granted the application of the land from

agricultural to residential and commercial use filed by Deogracias

through his attorney-in-fact, Moldex.

PARAD ultimately dismissed the complaint. It ruled that petitioner

failed to adduce evidence that the landowner gave his consent for

Caluzor to become tenant of the land. Caluzor failed to present

evidence he has a leasehold contract, and that any receipt of

payment for his alleged leasehold rentals. It is a well settled

doctrine that mere cultivation without proof of tenancy conditions

does not suffice to establish tenancy relations.

Before the DARAB

Caluzor appealed to the DARAB, and the latter ruled in favour of

Caluzor. It held that the institution of Caluzor as tenant in the land

and sharing of the produce sufficiently established tenancy

relationship between them. The subsequent conveyance of the land

to the heirs does not extinguish Caluzors right to till the land (See

Section 10, Agricultural leasehold relation not extinguished by

expiration of period, etc.).

Before the Court of Appeals

Deogracias and Moldex appealed the decision of the DARAB. The

CA revised the ruling of the DARAB and reinstated the decision of

PARAB. It held that the application for conversion of land was

granted because the land is no longer suitable for agricultural

production, the property has been classified as residential/

commercial, and MARO, PARO, RD, CLUPPI) recommended the

approval. In fact, subject land is not a developed subdivision. There

can be no agricultural tenant on a residential land.

With regards the disturbance compensation, the records are bereft

of evidence showing that Caluzor is tenant of Llanillo.

Hence, this recourse to the Supreme Court.

Issue:

Whether a tenancy relationship exists between Caluzor and Llanillo.

Ruling:

There is no tenancy relationship between Caluzor and Llanillo.

Tenancy relationship and entitlement to disturbance compensation

requires factual and legal bases. Section 5 provides that a tenant

shall mean a person who, himself and with the aid available from

his immediate farm household cultivates the land belonging to, or

possessed by another, with the latters consent for purposes of

production, sharing the produce with the landholder under the

share tenancy system, or paying to the landholder a price certain

or ascertainable in produce or in money or both, under the

leasehold tenancy system.

The following elements must concur: (PACPPH)

1, the parties are the landowner and tenant;

2, the subject matter is agricultural land;

3, there is consent between the parties and the relationship;

4, the purpose of the relationship is to bring about agricultural

production;

5, there is personal cultivation on the part of the tenant or

agricultural lessee;

6, the harvest is shared between landowner and tenant or

agricultural lessee.

The absence of one will not make an alleged tenant a de jure

tenant. Unless a person has established that he is a de jure tenant,

he is not entitled to security of tenure or to be covered by the land

reform program.

In establishing tenancy relationship, independent evince should

prove the consent of the landowner to the relationship and the

sharing of the harvest. In this case, the third and sixth elements

are not present.

Caluzor testified that Lorenzo allowed him to cultivate the land by

giving to him (Caluzor) the sketch of the lot in order to delineate

the portion of his tillage. Yet, the sketch did not establish that

Lorenzo had categorically taken the petitioner as his agricultural

tenant. This element (consent) demanded that the landowner and

tenant should have agreed to the relationship freely and voluntarily,

with neither of them unduly imposing his will on the other. In this

case, there is no showing of such consent.

Even assuming that Lorenzo permitted Caluzor to till the land, there

is still no tenancy relationship established because they had not

discussed any fruit sharing scheme, with Lorenzo simply telling him

that he would just ask his share from Caluzor. Petitioner disclosed

that he did not see Lorenzo after he received the sketch and until

Lorenzos death. Although he still continued sharing the

fruits through Ricardo evidenced by a list of produce to

support his claim, the list did not indicate Ricardos

receiving the fruits listed. It did not also contain Ricardos

authority to receive Lorenzos share.

The absence of the clear cut sharing agreement between Caluzor

and Lorenzo could only signify that the latter merely tolerated

Caluzors cultivation sans tenancy. It did not make him de jure

tenant. There must be concrete evidence on record

adequate to prove the element of sharing. To prove sharing

of harvests, a receipt or any other credible evidence must

be presented. Tenancy relationship cannot be presumed.

Leasehold tenancy is not brought about by mere

congruence of facts but, being a legal relationship, the

mutual will of the parties to that relationship should be

primordial.

To be entitled to disturbance compensation, one should be a de

jure tenant. The de jure tenant should allege and prove (1) the

cost and expenses incurred in the cultivation, planting, or

harvesting and other expenses incidental to the improvement of his

crop and (2) necessary and useful improvements made in

cultivationg the land.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Residential Lease AgreementDocument7 pagesResidential Lease AgreementpeteradrianPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Blank Letter of Intent Real Estate Lease DownloadDocument4 pagesSample Blank Letter of Intent Real Estate Lease DownloadRiver HousePas encore d'évaluation

- Real Estate MortgageDocument4 pagesReal Estate MortgageCyril OropesaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cadastral Registration ProceedingsDocument61 pagesCadastral Registration ProceedingspaultimoteoPas encore d'évaluation

- DAR-v-Carriedo-2018 Part 2Document2 pagesDAR-v-Carriedo-2018 Part 2Bill Mar100% (1)

- Ohio Residential Lease AgreementDocument8 pagesOhio Residential Lease AgreementSantonio CarterPas encore d'évaluation

- Nuñez v. VillanozaDocument2 pagesNuñez v. VillanozaAbby Abby100% (1)

- G.R. No. 188174 DAR V WOODLANDDocument1 pageG.R. No. 188174 DAR V WOODLANDRIZA WOLFEPas encore d'évaluation

- 20 Estribillo Vs Department of Agrarian Reform - CastilloDocument2 pages20 Estribillo Vs Department of Agrarian Reform - CastilloAb Castil100% (1)

- Jaime D. Dela Cruz v. PeopleDocument1 pageJaime D. Dela Cruz v. PeoplefcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of The SeaDocument5 pagesLaw of The SeafcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- PDIC Vs CasimiroDocument2 pagesPDIC Vs Casimirofcnrrs100% (2)

- Cabral v. Heirs of AdolfoDocument3 pagesCabral v. Heirs of AdolfoKarilee Salcedo Ayunayun67% (3)

- Rent Agreement Format MakaanIQDocument3 pagesRent Agreement Format MakaanIQsrinivas50% (2)

- Transfer of Property Law Notes IndiaDocument96 pagesTransfer of Property Law Notes IndiaArunaML100% (1)

- JV Lagon vs. Heirs of LeocadiaDocument3 pagesJV Lagon vs. Heirs of LeocadiaSORITA LAWPas encore d'évaluation

- Crisostomo v. VictoriaDocument2 pagesCrisostomo v. VictoriaLimar Anasco Escaso100% (1)

- Gabriel v. Pangilinan DigestDocument3 pagesGabriel v. Pangilinan DigestApple Lentejas - Quevedo100% (1)

- Land Reform Ruling Favors Landless TenantsDocument2 pagesLand Reform Ruling Favors Landless TenantsRhea Mae A. SibalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Milestone Realty and Co., Inc. v. Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesMilestone Realty and Co., Inc. v. Court of AppealsdollyccruzPas encore d'évaluation

- 02 - Heirs of Leonilo P. Nuñez, Sr. v. Heirs of Gabino T. VillanozaDocument2 pages02 - Heirs of Leonilo P. Nuñez, Sr. v. Heirs of Gabino T. VillanozaPaul Joshua SubaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vianzon vs. Macaraeg DigestDocument4 pagesVianzon vs. Macaraeg DigestLouPas encore d'évaluation

- Milestone Farms, Inc. vs. Office of The PresidentDocument4 pagesMilestone Farms, Inc. vs. Office of The PresidentVilpa VillabasPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Digest - SALAS VS CABUNGCAL GR 191545Document3 pages5 Digest - SALAS VS CABUNGCAL GR 191545Paul Joshua Suba50% (2)

- Gabriel V Pangilinan DigestDocument3 pagesGabriel V Pangilinan DigestYvey Rose CaringalPas encore d'évaluation

- SC Rules CA Erred in Ruling Livestock Lands AgriculturalDocument2 pagesSC Rules CA Erred in Ruling Livestock Lands AgriculturalPaul Joshua SubaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sources of International LawDocument8 pagesSources of International Lawfcnrrs0% (1)

- 8 DAR v. ROBLES - Peralta, J (Digest)Document2 pages8 DAR v. ROBLES - Peralta, J (Digest)Susie SotoPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAP 9 - Heirs of Gonzales v. de LeonDocument2 pagesCHAP 9 - Heirs of Gonzales v. de LeonShachia MicaellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Alarcon Vs CA Case Digest - Agrarian LawDocument3 pagesAlarcon Vs CA Case Digest - Agrarian LawDamien100% (1)

- Estate Tax and Some Exempt TransfersDocument3 pagesEstate Tax and Some Exempt TransfersfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- CENEZE VS. RAMOS: No Tenancy Relationship EstablishedDocument3 pagesCENEZE VS. RAMOS: No Tenancy Relationship EstablishedDiana BoadoPas encore d'évaluation

- POPARMUCO V InsonDocument2 pagesPOPARMUCO V InsonLawrence Y. Capuchino100% (1)

- SC Acquits Wagas of Estafa Due to Insufficient EvidenceDocument2 pagesSC Acquits Wagas of Estafa Due to Insufficient EvidencefcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- E Razon Vs Phil Ports AuthorityDocument1 pageE Razon Vs Phil Ports AuthorityfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Comment Legal FormsDocument2 pagesComment Legal Formsfcnrrs100% (1)

- LBP v. Rural Bank of Hermosa dispute over land valuationDocument1 pageLBP v. Rural Bank of Hermosa dispute over land valuationCecile FederizoPas encore d'évaluation

- Exclusionary Rules Evidence ConstitutionDocument1 pageExclusionary Rules Evidence ConstitutionfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Rent AgreementDocument3 pages1 Rent AgreementAmit A KulkarniPas encore d'évaluation

- Pagarigan vs Yague case summaryDocument8 pagesPagarigan vs Yague case summaryPhilippe CamposanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Victory Liner V GammadDocument1 pageVictory Liner V GammadfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurisdiction of DAR over agrarian casesDocument4 pagesJurisdiction of DAR over agrarian casesbrigettePas encore d'évaluation

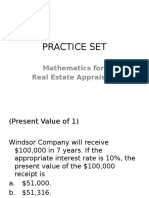

- Practice SetDocument39 pagesPractice SetDionico O. Payo Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act 2002Document161 pagesComprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act 2002fcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Manuel Jusayan v. Jorge SombillaDocument3 pagesManuel Jusayan v. Jorge SombillaDan LocsinPas encore d'évaluation

- 087 Hrs of Buensuceso Vs PerezDocument2 pages087 Hrs of Buensuceso Vs PerezcrisPas encore d'évaluation

- DARAB Jurisdiction Over Property Under CARP Retention LimitDocument2 pagesDARAB Jurisdiction Over Property Under CARP Retention Limitjilliankad100% (1)

- Traders Royal Bank v. CADocument2 pagesTraders Royal Bank v. CARam Adrias100% (1)

- Ferrer Vs Carganillo - CADIZDocument26 pagesFerrer Vs Carganillo - CADIZNikki Diane CadizPas encore d'évaluation

- LBP Vs Ciriaco, G.R. No. 206992Document2 pagesLBP Vs Ciriaco, G.R. No. 206992andek oniblaPas encore d'évaluation

- Landowners cannot question beneficiary qualificationsDocument1 pageLandowners cannot question beneficiary qualificationsrommel alimagnoPas encore d'évaluation

- 12 - Heirs of Sandueta v. Robles - TorresDocument2 pages12 - Heirs of Sandueta v. Robles - TorresNicole PTPas encore d'évaluation

- Agrarian Law (Hermoso vs. CL Realty)Document3 pagesAgrarian Law (Hermoso vs. CL Realty)Maestro LazaroPas encore d'évaluation

- CSC resolution invalidating appointment not subject to certiorari petitionDocument2 pagesCSC resolution invalidating appointment not subject to certiorari petitionfcnrrs100% (1)

- Mindanao Shopping V DuterteDocument2 pagesMindanao Shopping V DutertefcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Admin Case Digest Set As of 01-21-19Document2 pagesAdmin Case Digest Set As of 01-21-19MokeeCodilla0% (2)

- Landowner's consent and sharing of harvests absentDocument2 pagesLandowner's consent and sharing of harvests absentAr LinePas encore d'évaluation

- 194846-2015-Saguin v. People PDFDocument10 pages194846-2015-Saguin v. People PDFJeunice VillanuevaPas encore d'évaluation

- DAR Vs Robles, GR No. 190482Document3 pagesDAR Vs Robles, GR No. 190482Aileen Peñafil0% (2)

- Vianzon v. MacaraegDocument3 pagesVianzon v. MacaraegSusie SotoPas encore d'évaluation

- 04 Del Castillo Vs OrcigaDocument2 pages04 Del Castillo Vs OrcigaJermaeDelosSantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Pilipinas Shell v. Royal FerryDocument2 pagesPilipinas Shell v. Royal Ferryfcnrrs100% (2)

- Reformation of contracts denied in land sale disputeDocument1 pageReformation of contracts denied in land sale disputefcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- LEBRUDO Vs LOYOLA DIGESTDocument1 pageLEBRUDO Vs LOYOLA DIGESTrommel alimagnoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pangilinan vs. BalatbatDocument2 pagesPangilinan vs. BalatbatMichaelPas encore d'évaluation

- Dar Vs CuencaDocument2 pagesDar Vs CuencaSarahPas encore d'évaluation

- 37 Caluzor Vs LlanilloDocument2 pages37 Caluzor Vs LlanilloJanno SangalangPas encore d'évaluation

- Tenancy Dispute JurisdictionDocument15 pagesTenancy Dispute JurisdictionAilaMarieB.Quinto100% (1)

- Heirs of Sandueta v. RoblesDocument3 pagesHeirs of Sandueta v. RoblesPaul Joshua SubaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gabriel v. Pangilinan, G.R. No. L-27797, August 26, 1974, 58 SCRA 590Document2 pagesGabriel v. Pangilinan, G.R. No. L-27797, August 26, 1974, 58 SCRA 590Hazel Eliza MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Landbank Vs AranetaDocument1 pageLandbank Vs AranetarhobiecorboPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.sutton Vs Lim - G.R.no.191660Document5 pages1.sutton Vs Lim - G.R.no.191660patricia.aniyaPas encore d'évaluation

- DAR Vs Polo Coconut PlantationDocument1 pageDAR Vs Polo Coconut Plantationtimothymarkmaderazo0% (1)

- DAR v. WoodlandDocument1 pageDAR v. WoodlandMlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Roxas vs. DAMBA Net DigestDocument3 pagesRoxas vs. DAMBA Net DigestChristian Carl GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2012mendoza Landtitlesanddeeds Carl VianzonvmacaraegDocument1 page2012mendoza Landtitlesanddeeds Carl VianzonvmacaraegBianca Nerizza A. Infantado IIPas encore d'évaluation

- Jusayan v. SombillaDocument3 pagesJusayan v. SombillaMariel QuinesPas encore d'évaluation

- LAPULAPUSocleg Case DigestDocument4 pagesLAPULAPUSocleg Case DigestJennica Gyrl G. Delfin100% (1)

- Heirs of Cadeliña Vs CadizDocument9 pagesHeirs of Cadeliña Vs CadizMary Fatima Tolibas BerongoyPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. MolinaDocument3 pagesPeople vs. MolinaSahara RiveraPas encore d'évaluation

- Agrarian Law DigestsDocument9 pagesAgrarian Law DigestsNElle SAn FullPas encore d'évaluation

- CASE DIGESTS (Agra Law)Document20 pagesCASE DIGESTS (Agra Law)Miguel Anas Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Land Reform Case DisputeDocument1 pageLand Reform Case DisputeJay-ar TeodoroPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 CALUZOR v. Llanillo, July 1, 2015, G.R. No. 155580Document4 pages7 CALUZOR v. Llanillo, July 1, 2015, G.R. No. 155580SORITA LAWPas encore d'évaluation

- Wills, Succession, Contracts, and Marriage LawsDocument2 pagesWills, Succession, Contracts, and Marriage LawsfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Spouses Alcantra V Spouses BelenDocument2 pagesSpouses Alcantra V Spouses BelenfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Deductions On Gross EstateDocument5 pagesDeductions On Gross EstatefcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Malayan Insurance v. LinDocument1 pageMalayan Insurance v. LinfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Retail Trade Liberalization ActDocument1 pageRetail Trade Liberalization ActfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Revocable To Funeral ExpensesDocument1 pageRevocable To Funeral ExpensesfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Homar V People G.R. No. 182534 September 2, 2015Document1 pageHomar V People G.R. No. 182534 September 2, 2015fcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax 2Document3 pagesTax 2fcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate TaxationDocument7 pagesCorporate TaxationfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- 03 Coscolluela V SandiganbayanDocument2 pages03 Coscolluela V SandiganbayanfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- WWW 21 June 2017 EditedDocument3 pagesWWW 21 June 2017 EditedfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- 02 People V UlatDocument1 page02 People V UlatfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Transportation Law NotesDocument2 pagesTransportation Law NotesfcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ainiza Vs Spouses Padua (Digest)Document1 pageAiniza Vs Spouses Padua (Digest)fcnrrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Law Essay - Theories of Land LawDocument10 pagesLand Law Essay - Theories of Land LawnifhlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Tenant Security of Tenure Act 1981Document34 pagesLand Tenant Security of Tenure Act 1981ChristopherLewisPas encore d'évaluation

- De Murga vs. ChanDocument12 pagesDe Murga vs. ChanDaniel OcampoPas encore d'évaluation

- Leases and Licenses Case SummariesDocument9 pagesLeases and Licenses Case SummariesAndriana LoiziaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rent Control JudgmentsDocument30 pagesRent Control JudgmentsArun SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporation Bank DEPOSIT OF TITLE DEED - 2 - 2Document2 pagesCorporation Bank DEPOSIT OF TITLE DEED - 2 - 2Naresh RajuPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Law - Land TitlesDocument23 pagesCivil Law - Land Titlesesmeralda de guzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- 281-279 361 282 - 279 632 PDFDocument6 pages281-279 361 282 - 279 632 PDFraj soniPas encore d'évaluation

- 2009 ESDC Atlantic Yards Lease AbstractDocument3 pages2009 ESDC Atlantic Yards Lease AbstractNorman OderPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Laws Including Any Other Local Laws: Unit I-Introductory PrinciplesDocument28 pagesLand Laws Including Any Other Local Laws: Unit I-Introductory PrinciplesMrinalBhatnagarPas encore d'évaluation

- 2009 Consolidated Foreclosed Property ListDocument48 pages2009 Consolidated Foreclosed Property ListReal Property Solutions75% (4)

- Apartment Rules and RegulationsDocument2 pagesApartment Rules and RegulationsAvreilePas encore d'évaluation

- Top Real Estate EmployersDocument4 pagesTop Real Estate EmployersspencerPas encore d'évaluation

- Rent DeedDocument3 pagesRent DeedArun GoyalPas encore d'évaluation

- Pune Housing and Area Development Board (PHADB)Document2 pagesPune Housing and Area Development Board (PHADB)rutujaPas encore d'évaluation

- HoyDocument6 pagesHoyPaul Arman MurilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Leases and Licences in The Law of ConveyDocument22 pagesLeases and Licences in The Law of ConveyJESSICA NAMUKONDAPas encore d'évaluation

- PowerPoint-Rent Renewal Expiration PresentationDocument15 pagesPowerPoint-Rent Renewal Expiration PresentationMarkD.LevinePas encore d'évaluation

- 5000 Lakewood RD, Stanwood, WA Lease Contract FormDocument8 pages5000 Lakewood RD, Stanwood, WA Lease Contract Formjason walterPas encore d'évaluation

- Balbin V Register of Deeds of Ilocos SurDocument1 pageBalbin V Register of Deeds of Ilocos SurDach S. CasiplePas encore d'évaluation

- Agreement of Subdivision - Sofronio Quimson (Ate Beth)Document2 pagesAgreement of Subdivision - Sofronio Quimson (Ate Beth)Vince Gabriel PerrerasPas encore d'évaluation