Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Scaffolding Study

Transféré par

Danilo MoggiaCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Scaffolding Study

Transféré par

Danilo MoggiaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Systemic Therapies, Vol. 29, No. 4, 2010, pp.

7491

SCAFFOLDING AND CONCEPT FORMATION

IN NARRATIVE THERAPY:

A QUALITATIVE RESEARCH REPORT

HEATHER L. RAMEY

Brock University

KAREN YOUNG, MSW

ROCK (Reach Out Centre for Kids)

and Brief Therapy Training Centres International

DONATO TARULLI, PH.D

Brock University

In his most recent writings Michael White made extensive reference to the work

of Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky, taking up several Vygotskian concepts

(e.g., scaffolding) into a re-visioning of his narrative conversations maps. We

used observational coding to test Whites newly formulated scaffolding conversations map against actual process in therapy with children, and the current

paper is a qualitative report of our findings. We found that most speech turns

were codable at some level of the map, that children responded to therapists

scaffolding, and that therapists and children tended to proceed through the steps

of the map in single-session therapy. These findings demonstrate that Whites

model of therapy is observable and suggest that change occurred at the level

of language over the session. This study lays the foundation for future research

regarding potential links between Whites process and therapeutic outcomes.

In his most recent writings Michael White (2006, 2007) made extensive reference to the work of Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1978, 1987). Indeed, the

increasing use of ideas and terms such as distancing, space, scaffolding, social

Heather L. Ramey, Department of Psychology, Brock University; Karen Young, Manager of Clinical

Services, ROCK (Reach Out Centre for Kids), Training/Research Faculty, Brief Therapy Training

Centres International, and Donato Tarulli, Department of Child & Youth Studies, Brock University.

We thank Scot Cooper, Haldimand-Norfolk Resources, Education and Counselling Help (REACH),

and Reach Out Centre for Kids (ROCK), for generously granting us access to the data, and Scot also

for providing constructive input on all phases of the research. We also thank the children and youth and

their families who participated in the study.

Correspondence concerning this article should be directed to Heather Ramey, Department of Psychology, Brock University, 500 Glenridge Avenue, St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1, Canada. Email: heather.

ramey@brocku.ca.

74

Scaffolding and Concept Formation

75

collaboration, and personal agency in his work suggests a Vygotskian re-visioning

of his narrative conversations maps. This newest map developed by White (2007),

called the scaffolding conversations map, inspired the following research questions:

Do narrative therapy sessions demonstrate the type of conversation described in

Whites scaffolding conversations map? If so, do children respond to therapists

scaffolding by responding to therapists questions at the same level of the map?

Finally, do therapists and children proceed through the steps of the map over the

course of a single session? While we examined similar questions in a previously

published study (Ramey, Tarulli, Frijters, & Fisher, 2009), that report focused largely

on establishing the utility of a quantitative methodologysequential analysisfor

examining the dynamic, moment-to-moment unfolding of therapeutic social interactions over individual narrative therapy sessions. In the present report, we seek

to revisit these questions from the analytic vantage point of a qualitative, practicebased perspective. Accordingly, we draw extensively on specific examples from

individual narrative therapy sessions to illustrate our claims.

We begin by outlining a brief history of the theories that have informed Whites

(2006, 2007) thinking in narrative therapy, with particular attention to the most recent influence of Vygotskys (1978, 1987) work. We then summarize some concepts

from Vygotskys writings, how these influenced recent developments in narrative

practice maps, and how these developments informed our research questions. The

research and its results are then described in detail. We conclude with a discussion

of the implications of our findings for both practice and future research.

Development of the Theory and Practice of Narrative Therapy

White and Epstons narrative therapy began evolving in the 1980s with their foundational Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends, published in North America in

1990. In this work they drew on the theories of several philosophers and critical

thinkers and applied these theories to their practice, creating a new model of family

therapy built around the metaphor of stories. From that time White continued to

explore this story metaphor, over the years expanding his thinking and narrative

practice through the accommodation of the insights of many additional theorists.

White and Epston (1990) began exploring their story metaphor in therapy using

ideas from Bruner (1986) and Geertz (1986). These initial explorations led eventually to the formulation of cornerstone concepts in narrative therapy: externalizing and unique outcomes. Externalizing in narrative therapy involves naming,

objectifying, and even personifying the problem to separate people from dominant,

problem-saturated stories. These dominant stories often do not reflect peoples

preferred ways of being and may obscure alternative interpretations. Alternative interpretations, also known as unique outcomes or initiatives (White,

2006), are any stories, ideas, or events that would not have been predicted by the

dominant problem story. Intertwining with and elaborating on these notions are

Batesons (1979) ideas of explanation and change, Derridas (Derrida & Caputo,

76

Ramey et al.

1997) deconstruction, Geertz (1973) and Myerhoffs (1982, 1986) anthropological

contributions, Foucaults (1980) deliberation of power (see also Danaher, Schirato,

& Webb, 2000) and, finally, Whites (2007) vision of scaffolding in Vygotskys

(1978) zone of proximal development.

Michel Foucaults work appears to have had the most significant influence on

White (Duvall & Young, 2009; White, 1989), with White and Epstons (1990) narrative therapy approach clearly incorporating Foucaults ideas on the modern power/

knowledge nexus, the socio-political context it creates, and its constitutive effects

(Besley, 2002; White, 2002). Foucauldian notions of power (Danaher et al., 2000;

Foucault, 1980) lead to the practice of deconstruction in narrative therapy, which

manifests itself in a persistent questioning of the taken-for-granted (White, 2002,

2007). More specifically, deconstruction is accomplished by questioning the meaning and history of problems and other significant constructs that arise in therapy, and

by examining unique outcomes that fall outside the dominant story. Deconstruction

also takes place through the unpacking of dissembled or unrecognized practices

of power and disciplinary technologies of the self, and by questioning therapeutic

discourses themselves.

Instead of classifying and objectifying individuals, the narrative therapy practice

of externalization re-situates the problem outside of people, challenging cultural

discourses that pre-suppose that individuals can be categorized and their potentials

fully contained by those categorizations. Together with deconstruction, externalizing

the problem questions this social control and these normalizing truths, unsettling

the effects of modern power (White, 1989). The use of externalizing and deconstruction in therapy is intended to liberate people from labels, allow cooperation to

influence the effects of the problem, present opportunities for multiple interpretations, discourage conflict about blame, and encourage agency instead of feelings

of failure and oppression (White, 1989).

White (2007) later developed maps, such as the statement of position maps, to

guide narrative conversations. These maps suggest particular lines of questioning

for therapists to follow, assisting in the development of understandings of where

people stand in relation to problems and unique outcomes. The narrative therapist

does not attempt to lead clients to any specific understandings or ideas, but rather

creates opportunities for people to make discoveries. Although these maps for

therapy continue to be offered as a useful tool, they usually have been accompanied by the caution that a map is not the territory (Korzybski, 1933, p. 58); that

is, the steps on the map are only that, and cannot reflect or capture the emergent,

temporally open nature of what happens in the course of therapy.

Concept Formation and the Zone of Proximal Development

Vygotsky provided a basis for much of Whites more recent writing (e.g., White,

2006, 2007), leading White in new directions in defining the tasks and maps of

narrative therapy and opening space both for re-thinking narrative practice and for

Scaffolding and Concept Formation

77

incorporating research to analyze the performance of therapist tasks. Vygotsky

(1978) emphasized that learning was an achievement not of independent effort

but of social collaboration. A critical notion for White (2007) was the zone of

proximal development, which Vygotsky defined as the distance between the

actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and

the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under

adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers (p. 86). The zone of

proximal development bridges the gap between what is known and what is possible

to know, and it is in this gap that learning occurs. According to Vygotsky, the zone

of proximal development is traversed through social collaboration between a child

and some other adult or peer with greateror perhaps just differentknowledge

of a concept at hand. Traversing the zone of proximal development only can be

achieved if the developmental gap is broken down into manageable tasks. It is

these tasks, which are structured at first but allow for the gradual progression from

collaborative to independent performance, that scaffold childrens development of

concepts. Verbal interactions provide the starting point for concept formation. The

learning collaborator or partner assists the child to distance from their immediate

experience and thereby to stretch her or his mind (White, 2007, p. 272), making new connections that lead to the development of higher-level thinking. This

makes it possible for concepts about life and identity to develop, which supplies

the foundation for deliberate actions to shape the course of life (White, 2007).

Wertsch (1985) applied the term decontextualization to Vygotskys emphasis

on the abstraction and generalization inherent in concept development. Decontextualization may be seen as a process involving the creation of a universal concept

that is readily applied to different contexts. As applied to narrative therapy, decontextualization, or concept formation, is a way of rethinking externalizing. The

process of externalizing does not produce a concept that is free from context, but

rather broadens and shifts it, making it more readily available for use. The concept

becomes de-limited, not unlimited, distancing the client from the known and

familiar (White, 2006, p. 39).

The Turn to Vygotsky in Mapping Narrative Conversations

Using Vygotskys theories of development and learning, White (2006, 2007) created a revised version of his statement of position maps. The first version of the

statement of position map focused on externalizing the problem, the second on

the initiative, and this third, latest version accommodates either the problem or the

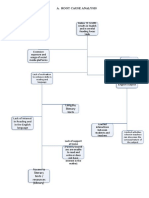

initiative. Known as the scaffolding conversations map (see Figure 1), it outlines

the therapists tasks in introducing concepts pertaining to client problems and

initiatives and scaffolding the clients mastery of them. In the current study, this

map serves as the basis for coding observations of therapist and client speech turns.

In the scaffolding conversations map the narrative therapists role is elucidated

as supporting people in distancing themselves from the known and familiar that is

78

Ramey et al.

FIGURE 1. Sample scaffolding conversations and coding map. Samples in quotes

are all therapist statements taken from White (2007, pp. 223227).

Distancing level/Code

Possible to know

Very high level (Plans)

High level (Intentions)

Medium-high (Evaluate)

Do you know why this development

makes you feel good?

Whats it like for you to see

this happening . . . ?

Medium level (Consequences)

Low level (Name)

What happened after this . . . ?

It was about

walking away from trouble.

Known and familiar

Time

being reproduced in their relationships with problems. The therapist provides scaffolding by asking incremental questions that support movement from the known

and familiar to what is possible to know and do. The therapist and client work in

partnership to traverse the zone of proximal development. The therapists scaffolding allows clients to distance themselves from aspects of problems so that they

can develop new conceptions of self, identity, problems, and resources. Distance

and increased mastery over concepts invite clients to gradually exercise personal

agency over the problems they are struggling with, or with the solutions they may

have already begun to find, but that may be lacking a strong foundation for continuance. This is in keeping with the notions of mastery and voluntary control/personal

agency that Vygotsky (1987) associated with conceptual thought.

The scaffolding conversation is organized according to a hierarchy, with increasing levels of generalizations that parallel the steps in the statement of position

maps. In accordance with this hierarchy, the revised map begins with naming and

characterizing the problem or initiative. For Vygotsky, developing words formed

the most primitive level of understanding concepts, and in this version of the map

White (2006) referred to this step as low-level distancing (p. 45). This marks the

early stages of concept formation, as unthematized, unorganized, and unconnected

Scaffolding and Concept Formation

79

experiences are united under a common name or category. Medium-level distancing

is the next step in the map, and these tasks produce chains of association between

the problem or initiative and its consequences, a step previously described as exploring the effects of the problem or initiative. White clearly correlated his second step

with Vygotskys notions of the development of complexes and chains of association, which establish objective (but not yet abstract) relationships between objects

or events. Medium-high-level distancing tasks (previously known as evaluating

the effects of the problem or initiative) have the client reflect on these chains of

association. In high-level distancing tasks (justifying and explaining evaluations,

according to earlier versions of Whites conversational maps) clients are invited to

generalize their learning from specific circumstances into other areas of their lives.

White stated that it is at this level, where learnings are both generalized from the

concrete and abstracted from the totality of experience, that the formation of concepts occurs. Very high-level distancing tasks, which were not formally included in

previous maps, invite clients to make plans of action based on the newly understood

concepts and the positions they have taken.

While the specific tasks of the partner/collaborator in the zone of proximal development received relatively little attention from Vygotsky (1978), he was quite clear

that instruction should be pitched ahead of the childs actual level of development.

In the context of narrative therapy, this means that therapists leading activities

should occur ahead of clients abilities, preceding (and indeed, promoting) their

development. Theoretically, then, both childrens and therapists tasks can be seen

in Whites map. The levels of a therapists leading questions and a childs responses

on the map should be readily available to observation. For example, if a child

switches from one aspect of an externalization to another, as would be expected at

the complex stage, the therapists task in the zone of proximal development might

be observed as re-circulating language (Duvall et al., 2003) so that it consistently

directs attention to those elements that the client denotes as relevant.

According to Whites (2006) utilization of Vygotsky (1978, 1987), the overarching tasks of the therapist are: to abstract elements from the totality of clients

experiences; to foreground clients current base of knowledge about concepts and

to make this knowledge more available to clients without their being fully defined

by the concepts; to develop these concepts more richly; and ultimately to assist

people in revising their relationship with concepts, thereby expanding their options.

A successful outcome will lead to the clients improved self-mastery in functioning.

All of this is accomplished through the tasks the therapist and subsequently the

clients perform, as outlined in Whites scaffolding conversations map.

The current study aimed to examine the scaffolding process in the zone of proximal development, as defined by the client-therapist interactions. This research was

the first known attempt to empirically study therapist and client movement through

the stages of the map. Toward that end, the following section provides a review of the

extant research literature on the externalizing process that White (2007) delineated

in the statement of position and scaffolding conversations maps.

80

Ramey et al.

Externalizing in Narrative Therapy

Few studies exist on the externalizing process in narrative therapy. None that we

found looked at Whites maps explicitly, and none included in its definitions or

analysis the full richness of the externalizing process as White more clearly described it in his maps and in the later years of his work (e.g., White, 2007).

Some steps on the map, such as naming the problem and recognizing unique

outcomes, have arisen in examinations of client and therapists descriptive experiences of narrative therapy (OConnor, Meakes, Pickering, & Schuman, 1997;

OConnor, Davis, Meakes, Pickering, & Schuman, 2004), but overall the findings

from these studies suggest that these aspects of externalizing, which are situated

earliest on the map, played a smaller role than other aspects of narrative therapy,

such as reflecting teams and respectful therapist posture. In contrast, studies that

have analyzed language in counselling session (Kogan & Gale, 1997; Muntigl,

2004) suggest that therapists emphasis on naming the problem and its effects have

aided client development of resources in meaning-making and in shifting client

language around problems and unique outcomes.

Even fewer studies have examined outcomes in narrative therapy as they relate to

externalizing, and these findings also have been mixed. A single-case study by Besa

(1994) relied on naming the problem and its effects as the initial, baseline period

of therapy, and no change was observed until the implementation of behavioral

contracts in subsequent sessions. A study by Weber, Davis, and McPhie (2006)

was hampered by an insufficient number of participants for statistical analyses,

although in qualitative reports participants identified that naming and characterizing

the problem contributed to a sense of increased personal agency. Most informative, however, is a recent study by Matos, Santos, Gonalves, and Martins (2009),

which found that unique outcomes and metacognitive reflections were associated

with problem-reduction.

The study by Matos et al. (2009) is the most rigorous of the outcome studies

and also provides the most positive evaluation of the outcomes of externalizing. Its

evaluation of narrative therapy process, however, relied on the authors own coding

system, rather than on Whites formulation. In contrast, the present study extends

previous research on aspects or individual steps of the externalizing process by

examining Whites (2006, 2007) more recent, broader definition of externalizing,

as clarified in the scaffolding conversations map.

Research Questions

In this study we sought to examine whether narrative sessions demonstrated the

type of conversation described in Whites (2006, 2007) scaffolding conversations

map. If this concordance could be observed, we sought further to explore whether

children responded to therapists scaffolding by responding to therapists at the

same level of the map, and whether therapists and children proceeded through the

Scaffolding and Concept Formation

81

steps of the map over the course of a single session. In this latter regard, we are not

suggesting that therapists will necessarily move through the complete scaffolding

conversations map in single session, nor that it is preferable to do so, but only that

it is possible to do so and hence worth exploring.

PARTICIPANTS AND CODING

In this study, we used previously recorded videos of eight single sessions of narrative

therapy. Children and youth were 6 to 15 years of age, and usually were participating

in services at one of two childrens mental health agencys walk-in clinics (Young,

Dick, Herring, & Lee, 2008). Children and parents specifically consented to the

use of the data for the current study. The therapists had not previously met with

any of the children and youth, who had a variety of reasons for coming to therapy,

such as worry, fear, and ADHD. Three therapists were involved in the study, each

a well-established narrative therapist who also had a history of providing training

in narrative therapy. One of the therapists (Karen Yang) is also an author of this

article. Any concerns that therapists usual practices may have been altered by a

prior knowledge of the research were mitigated by the fact that the study had not

been conceived at the time of the recorded sessions.

Coding

Each of the video recordings was transcribed verbatim; then, using the transcript,

each therapist and child speech turn was coded according to its corresponding

step on Whites (2006, 2007) scaffolding conversations map. The coding system

comprised five categories or levels, each of which applied equally to both therapist and client contributions to the process, with an additional code of Other for

utterances that did not fall into any of the existing categories. These codes, along

with examples of their use, are described more fully below. As the more detailed

procedures for coding and establishing inter-rater reliability are described in depth

in a previous publication (Ramey et al., 2009), they will not be repeated here. It

bears noting, however, that the therapists who conducted the sessions were not

involved in coding the sessions and that a manual (available from the corresponding author upon request) was prepared to describe therapist and client coding in

detail and to guide raters.

To demonstrate the coding system, we will describe each of the levels as they

were coded, and provide an example from a transcript by Michael White (2007).

In the example we will use, White was meeting with Peter, a 14-year-old with a

history of angry outbursts and criminal charges. Peters referring therapist noticed

that Peter had lately been involved in a situation that he found very frustrating, but

Peter chose to leave the room rather than lashing out. In each of the quotes from

the sample, White made a statement or asked a question about Peters initiative, and

82

Ramey et al.

Peter responded at the same level of coding. This observed pattern was not assumed

to be the case in the sessions under studyindeed, whether such a pattern could

be detected was one of our research questions; we draw on these examples only to

illustrate and simplify the explanation of the various levels of the coding system.

Name. In the first level, therapists and childrens speech turns included naming

or characterizing problems or unique outcomes/initiatives. This often involved the

therapist re-circulating significant child language. Names and characterizations

were offered by children spontaneously or invited through therapist questions or

suggestions. As part of characterizing the externalization, speech turns coded Name

also included conversation about the history of problems or initiatives, or the tactics

and strategies used by the problem. In the conversation between White (2007) and

Peter, White responded to a statement from Peter by saying, So thats a name for

what you did? It was about walking away from trouble. Peter confirmed Whites

statement and elaborated on it, saying Yeah. I figured, Who needs it? (p. 223).

In our coding system, these both would be coded as Name.

Consequences. In the second level, chains of association were made between

problems and initiatives and consequences in childrens lives. Speech turns focused

on the effects or potential effects of the problem or initiative on aspects of childrens

lives, such as their relationships, behaviour, or feelings about themselves.1 In the

sample from Whites (2007) transcript, White asked about the effects walking away

had on Peters life: What did this make possible for you? . . . What happened after

that wouldnt have happened if youd lost it? Peter responded at the same level:

I kept my privileges . . . Weekend leave. My metalwork class. I didnt have to go

to counseling (p. 224).

Evaluate. In the third level of coding, therapists and children drew realizations and learnings about these consequences. This included therapists inviting

or children spontaneously presenting an evaluation, or statement of position, on

the problem or initiative or its effects. These statements indicated where children

stand in regard to the problem or initiative. Occasionally, this level also included

other realizations about the problem or initiative or its effects as new learnings

emerged about previously established chains of associationfor example, what

children felt the problem needed or what should be done to it. At this level White

(2007) summarized the changes Peter had made, and asked What is it like for

you to see this happening in your life? and Peter responded, Its good to see I

suppose . . . Its positive (p. 227).

Intentions. At the fourth level of coding, therapists and children reflected on

realizations from the previous level (Evaluate), and childrens statements about

1Michael

White has used the terms consequences, effects, and chains of association to describe

this level of scaffolding. We will use the term consequences for the remainder of this paper, as it is

clearer than chains of association, and avoids the connotations of the term effects, particularly in

the context of its use in experimental research designs (e.g., main effects, program effects).

Scaffolding and Concept Formation

83

what they want with regard to the problem or initiative were connected to what

children value and intend for their lives. Speech turns were about the broader

purposes, beliefs, intentions, hopes, wishes, commitments, or dreams children or

youth have for their lives or identities. At this level, White (2007) asked Peter to

explain why walking away from trouble and other changes were positive: Do you

know why this development makes you feel good . . . Why is getting somewhere

important to you?, and Peter replied Because Ill be able to do something with my

life . . . Ill be able to say what I want and do something about it (pp. 227228).

Plans. In the final level, therapists and children expanded their conclusions into

plans. Speech turns involved next steps, possibilities, or outcomes, given childrens

conclusions and what they want for their future. Making plans included using what

had been learned about problems, expanding on initiatives, and recruiting support

systems. There are no speech turns at this level in the section of transcript from White

(2007), but it is possible to imagine that speech turns at this level might include

plans to do something that worked in the past, such as Peter reminding himself that

he has done this before and that he wants a say in the direction of his life.

Other. Any speech turn that did not correspond with one of the steps on the map

was coded as Other.

In the example with Peter it is an initiative, namely walking away from trouble,

that is the focus of the scaffolding and concept formation conversation. However,

as White (2006, 2007) incorporated both problems and initiatives in his revised

version of the map, both were included in the sessions coded in the current study.

This first level of coding for the therapist and child speech turns was used for

the initial frequency counts. Once the first level of coding was complete, speech

turns were paired, so that each therapist speech turn and the following child speech

turn contained two units of coding, but each pair contributed one data point to the

analysis. Speech turn pairs were also coded according to whether they occurred

in the beginning, middle, or end of the session, to see if the patterns of talk were

different at different points in the session.

Analysis

In addition to simple descriptive data on whether and how often therapists and

childrens statements corresponded with the levels of the map, the original quantitative study relied on sequential analysis (Bakeman & Gottman, 1997). As its name

indicates, sequential analysis allows for the examination of sequential behaviors,

to discover what patterns of serial behaviors occur in social interactions. The use

of sequential analysis allowed us to determine whether children were significantly

more likely to respond at the same level of the map as the therapist, rather than

pursuing conversation at another level of the map or another line of discussion

altogether. It also allowed us to examine whether the conversation advanced along

the steps of the map over the course of the session.

84

Ramey et al.

RESULTS

Overall Frequencies

In total, more than 2,300 individual speech turns were coded. Overall, therapist

and child speech turns were most frequently coded as Name (46% and 47%, respectively), followed at some distance by speech turns at other levels. The coding

frequencies were as follows: Consequences (therapist 14%, child 13%), Evaluate

(6%, 6%), Intentions (12%, 12%), Plans (10%, 9%), and Other (13%, 13%).

The coding frequencies tell us a number of things about what occurred in the

sessions. First, in light of the fact that relatively few speech turns were coded as

Other, and in answer to our first research question, most therapist and child speech

turns were codable at some level of the scaffolding conversations map. In the sessions under study, therapists and childrens speech turns matched some level of the

map approximately 87% of the time. Also interesting was the distribution of the

codes. Almost half of the speech turns were dedicated to naming and characterizing

the problem or initiative, perhaps the most widely recognizable aspect of narrative

therapy. The remainder of therapists and childrens speech turns were coded at

the levels of Consequences, Intentions, Plans, and Other an approximately equal

number of times, with somewhat fewer speech turns dedicated to the Evaluate level.

The Other category was not broken down more precisely, so the conclusions that

can be drawn from it are limited. However, speech turns at this level sometimes

contained discussion about strengths and interests, and about other people in the

childrens lives, such as parents and coaches. These might simply be considered

ways to facilitate joining, but such questions also might have acted as precursors

to the final level, Plans, as the information gathered sometimes contributed to the

development of plans to recruit support people or build on strengths in the future.

Further analysis was necessary to provide answers to our second and third research questions. To analyze the coded data, the paired therapist-child speech turns

first were compiled in a frequency table (see Table 1 for a condensed version). We

have also made extensive use of the qualitative data contained in the transcripts to

explore these questions and further illustrate our findings.

TABLE 1. Frequencies (and Percentages) of Therapist by Child Codes (N = 1187)

Child/youth level

Therapist level

Name

Consequences

Evaluate

Intentions

Plans

Name

Consequences

Evaluate

Intentions

Plans

Other

502 (42.3%)

18 (1.5%)

2 (0.2%)

5 (0.4%)

4 (0.3%)

11 (0.9%)

18 (1.5%)

134 (11.3%)

3 (0.3%)

3 (0.3%)

2 (0.2%)

5 (0.4%)

5 (0.4%)

8 (0.7%) 4 (0.3%)

2 (0.2%)

0 (0.0%) 3 (0.3%)

54 (4.6%)

7 (0.6%) 2 (0.2%)

7 (0.6%) 117 (9.9%) 0 (0.0%)

0 (0.0%)

1 (0.1%) 95 (8.0%)

3 (0.3%)

4 (0.3%) 9 (0.8%)

Other

16 (1.4%)

1 (0.1%)

2 (0.2%)

10 (0.8%)

4 (0.3%)

126 (10.6%)

Scaffolding and Concept Formation

85

Therapist Scaffolding

In answer to our second research question, we found that children responded to the

scaffolding provided by the therapists, as indicated by their tendency to respond at

the same level of the scaffolding conversations map. This tendency is illustrated

by the following excerpts from the transcript data:

Example Name:

Therapist: Can you think of times when ADHDs tried to get the steering wheel

but youve managed to take it yourself?

Child: Helping out with the gardening.

Example Consequences:

Therapist: Whereabouts does [the ADHD] get you in trouble?

Child: Fighting with [my brother].

Example Evaluate:

Therapist: How do you feel about that now?

Child: I feel good that I didnt do it.

Example Intentions:

Therapist: Why would you worry about that?

Child: Because I want to be strong and get bigger.

Example Plans:

Therapist: How can your mom and dad help for back up?

Child: Maybe talk to me in private sometimes, to see how its going.

Movement Through the Map

Our third research question was whether therapists and children proceeded through

the steps of the map over the course of single sessions of therapy. Again, as expected, we found that both therapists and children tended to move away from the

earlier stages in the map and toward later stages of the map over the course of a

single session. The following therapist quotes are all taken from the same session,

and illustrate this movement.

Example, early in session:

Is it okay to call it perfectionism? (Name)

What else does perfectionism demand from you? . . . Does it demand of you to act

certain ways with people or be certain ways with people? (Consequences)

86

Ramey

Example, mid-session:

So, if you were going to evaluate this on sort of like it/dont like it, appreciate it/dont

appreciate it, or even good/bad, where would that be? (Evaluate)

Does that have to do with that idea of Im fine how I am . . . And I guess Im talking

about it because I think that the more you can understand that to be a big part of yourself and who you are, the more you have some words to describe that, kind of like the

more available it can be to you. (Intentions)

Example, later in session:

I wonder if there might be some way that you can actually begin to protest this? To

protest the way that perfectionism creates frustration for you. (Plans)

Our results show that childrens movement across the stages of the map was similar

to therapists movement.

Example, early in session:

Its a little bit of feeling worried, a little bit of stomach acid, and burning. (Name)

[The worry] kind of tells me to feel the pain sometimes, because it doesnt want me

to do something sometimes. (Consequences)

Example, mid-session:

I just really dont want to think about the worry. (Evaluate)

Example, later in session:

[Because the worry] kind of makes me not believe in myself. It makes me think that I

cant do it. Its like almost the exact opposite of, that I can believe in myself. (Intentions)

[I could ask my parents] about what I should do if I feel sick. What they did about

their worries when they were a kid. Like, they might have got their parents to help

them or something, and my dad, hed probably tell me and it could just work! (Plans)

DISCUSSION

The results demonstrate that therapists and children and youths conversations were

reliant on the scaffolding conversations map, primarily at the level of naming and

characterizing the problem, but also at the four other levels of externalizing. In

answer to our first research question, whether narrative therapy sessions demonstrate

the type of conversation described in Whites scaffolding conversations map, we

found that the majority of speech turns were coded at one of these levels of the map.

Also of interest, almost half of the speech turns were coded at the first level of the

map, naming and characterizing the problem. Although this study was a process

Scaffolding and Concept Formation

87

analysis and did not consider outcomes, the high proportion of therapist questions

and statements at the first level of the scaffolding conversations map suggests that

naming and characterizing the problem is an important part of narrative therapy.

In answer to our second question, the results indicated that when therapists offered a statement or question, children and youth were likely to reply at the same

level of externalization. In other words, we found that children tended to respond

to therapists scaffolding by responding to therapists questions or statements at

the same level of the map.

In answer to our third research question, the results also indicated that both therapists and children and youth demonstrated movement through the general steps of

externalizing during single-sessions of therapy. According to Whites interpretation of

Vygotsky (1978, 1987), therapists tended toward increasing levels of scaffolding and

children tended toward increasing levels of concept formation as the session progressed.

It may be taken as self-evident that children follow the lead of therapists in

therapeutic conversations. The scaffolding metaphor certainly suggests this much:

through the linguistic scaffold constituted by externalizing talk the therapist assists the client in moving toward ways of thinking and speaking that afford the

latter greater choice for action and increased opportunities for self-reflective engagement with multiple voices and narratives (Par & Lysack, 2004), all toward

the end of enhancing possibilities for self-definition. However, it is in no way a

natural consequence that children mechanically follow the reasoning or language

of adult therapists, nor, more generally, that they play a passive role in therapeutic

conversations. As Par and Lysack (2004) have argued, although the therapist may

introduce the externalizing talk into the therapeutic conversation,

clients can and do bring material to therapeutic conversations that subsequently provide

structure for co-shaping meanings. Like the non-metaphorical sense of the worda

temporary structure for aiding in constructionthe scaffold that [the therapist] introduces is subsequently reshaped and modified by both he and [the client] through

their responses to each other. (p. 13)

It is also important to note in this regard that Vygotsky (1934/1987) himself strongly

disputed the belief that imitation is independent of understanding. Vygotsky stated

that children can only imitate what lies within their potential:

if I do not know higher mathematics, a demonstration of the resolution of a differential

equation will not move my own thought in that direction by a single step. To imitate,

there must be some possibility of moving from what I can do to what I cannot (p. 209).

In considering the stages of Whites map, blind imitation must have been especially

unlikely at higher levels of externalizing, as children had to comprehend lower

levels of externalizing sufficiently to respond and formulate new understandings

based on prior therapist scaffolding. The intricacy of this task is apparent in the

following example from the transcripts:

88

Ramey

Therapist: So, worry kind of equals, is the same thing as, thinking about the bad

feeling. So your wish for yourself is . . .

Child: Is, I really dont want the pain anymore. I dont want to think about the

worrying anymore because it really hurts and it makes me think that I cant do

it when I actually can, and like, so many people tell me that I actually probably

could and the worry tells me that they are wrong but like the people who tell me

this are actually right, it just takes me a little while to figure out they are right,

because I feel better over time . . .

In the example (see also Young, 2008), the therapist briefly summarized at the

first level of the map, naming and characterizing the problem, and scaffolded with

a question at the fourth level, regarding intentions the child has for his life. The

child responded with his wish for a life without the pain or worry, at the same time

drawing together evaluations and realizations from earlier in the conversation (including the realizations that the worry lies, that the hurting is an effect of the worry,

and the feeling better is an effect of his initiatives into carrying on despite the

worry). Such complex responses were not unique, and do not demonstrate speech

or behaviour that is automatic, mechanical, or passively repetitive of authoritative

therapeutic discourse; rather, they disclose childrens active efforts to appropriate

the linguistic resources of the therapeutic encounter (cf. Muntigl, 2004).

Limitations and Future Directions

As already noted, the study reported here did not attempt to establish effectiveness

or efficacy outside of sessions. Further, as it involved a limited number of therapists,

clients, and sessions, the results are not necessarily generalizable or reflective of

narrative therapy as such. The study also was limited to the statement of positions

maps (externalizing, unique outcomes) and their incarnation in the scaffolding

conversations map. It was not possible to incorporate other maps used in narrative

therapy, such as the re-membering or re-authoring maps (White, 2007), within

the limited scope of this study. Future directions for research might include the

longer-term use of narrative therapy, replication with other therapists, children, and

youth, the use of other narrative therapy maps and, with caution, outcome research.

Implications

The current study has implications both for research and practice. With regard

to research, the findings demonstrate that Michael Whites (2006, 2007) model

of therapy is observable in sessions. This opens the door for further research on

process in narrative therapy, possibly as described above. Also, although the nonexperimental research design does not allow us to attribute changes in childrens

language specifically to the therapist scaffolding, the findings do suggest that change

occurred at the level of language over the course of the session. As such, this

Scaffolding and Concept Formation

89

study lays the foundation for research questions regarding potential links between

Whites process and therapeutic outcomes around childrens thinking and actions

outside of sessions.

It must be noted, however, that the current study was not an attempt to manualize process in narrative therapy in order to lay the groundwork for effectiveness or efficacy research. Rather, it wasin partan attempt to respond to

Foucauldian ideals in establishing a self-reflective platform for offering therapy

by evaluating Whites (2006) ideas about what narrative therapy is intended to

accomplish. Such systematic self-reflection is necessary for therapists to be accountable to the people who consult with them. We believe that research is a form

of self-examination, as it involves re-visiting (Young & Looper, 2008) therapy

work that has been done, and thus can provide one, although not the only, tool

for self-reflection. Nonetheless, and despite the usefulness of research as a form

of systematic self-reflection, research alone should not drive therapy. Research

findings must be balanced by other contributions to practitioner knowledge, and

research in narrative therapy must be conducted with attention to the philosophical foundations provided by Foucault (White & Epston, 1990).

With regard to implications for practice, the findings demonstrate that the narrative therapy approach of scaffolding and the use of maps can be learned by therapists

other than Michael White; the model that White (2006, 2007) has presented is reproducible. As well, in supporting Whites claim that scaffolding and concept formation

occur in session, the study clarifies what is happening in narrative conversations.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings indicated that Whites (2006, 2007) scaffolding conversations

map and model of therapy was observable in single-sessions of therapy with children

and youth. Patterns of therapists and children and youths interactions demonstrated

Whites interpretation of scaffolding and the development of concept formation. The

occurrence of change in a therapy session, with its potential to influence subsequent

action, is the first step toward change in a child or youths life.

REFERENCES

Bakeman, R., & Gottman, J. M. (1997). Observing interaction: An introduction to sequential

analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and nature. New York: E. P. Dutton.

Besa, D. (1994). Evaluating narrative family therapy using single-system research designs.

Research on Social Work Practice, 4, 309325.

Besley, A. C. (2002). Foucault and the turn to narrative therapy. British Journal of Guidance and Counseling, 30, 125143.

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

90

Ramey

Danaher, G., Schirato, T., & Webb, J. (2000). Understanding Foucault. London: Sage.

Derrida, J., & Caputo, J. D. (1997). Deconstruction in a nutshell: A conversation with Jacques

Derrida. New York: Fordham University Press.

Duvall, J., Katz, E., Chambon, A., Mishna, F., & Beres, L. (2003). Narrative Research Project

phase 1 report: Research as retelling (20022003). Toronto: Brief Therapy Training

CentersInternational HincksDellcrest Centre and the Faculty of Social Work,

University of Toronto. Retrieved October 27, 2009 from www.hincksdellcrest.org

Duvall, J., & Young, K. (2009). Keeping the faith: A conversation with Michael White.

Journal of Systemic Therapies, 28, 118.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 19721977

(Colin Gordon, Ed. & Trans.). New York: Pantheon Books.

Geertz, C. (1986). Making experience, authoring selves. In V. W. Turner & E. M. Bruner

(Eds.), The anthropology of experience (pp. 373380). Chicago: University of Illinois

Press.

Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description: Toward an interpretative theory of culture. In The

interpretation of cultures (pp. 330). New York: Basic Books.

Kogan, S. M., & Gale, J. E. (1997). Decentering therapy: Textual analysis of a narrative

therapy session. Family Process, 36, 101126.

Korzybski, A. (1933). Science and sanity: An introduction to non-Aristotelian systems and

general semantics. Lakeville, CT: International Non-Aristotelian Library Publishing

Company.

Matos, M., Santos, A., Gonalves, M., & Martins, C. (2009). Innovative moments and change

in narrative therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 19, 6880.

Muntigl, P. (2004). Ontogenesis in narrative therapy: A linguistic-semiotic examination of

client change. Family Process, 43, 109131.

Myerhoff, B. (1982). Life history among the elderly: Perfomance, visibility, and remembering. In J. Ruby (Ed.), A crack in the mirror: Reflexive perspective in anthropology

(pp. 99117). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Myerhoff, B. (1986). Life not death in Venice: Its second life. In V. W. Turner & E. M.

Bruner (Eds.), The anthropology of experience (pp. 261286). Chicago: University

of Illinois Press.

OConnor, T. S., Davis, A., Meakes, E., Pickering, M. R., & Schuman, M. (2004). Narrative

therapy using a reflecting team: An ethnographic study of therapists experiences.

Contemporary Family Therapy, 26, 2339.

OConnor, T. S., Meakes, E., Pickering, M. R., & Schuman, M. (1997). On the right track:

Client experience of narrative therapy. Contemporary Family Therapy, 19, 479495.

Par, D., & Lysack, M. (2004). The willow and the oak: From monologue to dialogue in the

scaffolding of therapeutic conversations. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 23, 620.

Ramey, H. L., Tarulli, D., Frijters, J. C., & Fisher, L. (2009). A sequential analysis of externalizing in narrative therapy with children. Contemporary Family Therapy, 31, 262279.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes

(M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In R. W. Rievery & A. S. Carton (Eds.) &

N. Minnick (Trans.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky, Volume 1: Problems of

general psychology (pp. 39285). New York: Plenum Press.

Scaffolding and Concept Formation

91

Weber, M., Davis, K., & McPhie, L. (2006). Narrative therapy, eating disorders and groups:

Enhancing outcomes in rural NSW. Australian Social Work, 59, 391405.

Wertsch, J. V. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

White, M. (1989). Selected papers. Adelaide, Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications.

White, M. (2002). Addressing personal failure. The International Journal of Narrative

Therapy and Community Work, 3, 3376.

White, M. (2006). Externalizing conversations revisited. In A. Morgan & M. White (Eds.),

Narrative therapy with children and their families (pp. 256). Adelaide, Australia:

Dulwich Centre Publications.

White, M. (2007). Maps of narrative practice. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: W.W.

Norton & Company.

Young, K. (2008). Narrative practice at walk-in therapy: Developing childrens worry inside.

Journal of Systemic Therapies, 27, 5474.

Young, K., Dick, M., Herring, K., & Lee, J. (2008). From waiting lists to walk-in: Stories

from a walk-in therapy clinic. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 27, 2339.

Young, K., & Cooper, S. (2008). Toward co-composing an evidence base: The narrative

therapy re-visiting project. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 27, 6783.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Mighty Metaphor A Collection of Therapists Favourite Metaphors and AnalogiesDocument13 pagesMighty Metaphor A Collection of Therapists Favourite Metaphors and AnalogiesCern Gabriel100% (1)

- Mycroanalysis in Communication PsychotherapyDocument20 pagesMycroanalysis in Communication PsychotherapyEvelyn PeckelPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence Base For DIR 2020Document13 pagesEvidence Base For DIR 2020MP MartinsPas encore d'évaluation

- Louis G. Castonguay, J. Christopher Muran, Lynne E. Angus, Jeffrey A. Hayes, Nicholas Ladany, Timothy Anderson-Bringing Psychotherapy Research to Life_ Understanding Change Through the Work of Leading.pdfDocument401 pagesLouis G. Castonguay, J. Christopher Muran, Lynne E. Angus, Jeffrey A. Hayes, Nicholas Ladany, Timothy Anderson-Bringing Psychotherapy Research to Life_ Understanding Change Through the Work of Leading.pdfDanilo Moggia100% (2)

- Caetano-Defining Personal Reflexivity-A Critical Reading of Archer's Approach (Febrero)Document16 pagesCaetano-Defining Personal Reflexivity-A Critical Reading of Archer's Approach (Febrero)Luis EchegollenPas encore d'évaluation

- Session No. 5: Growing in The SpiritDocument6 pagesSession No. 5: Growing in The SpiritRaymond De OcampoPas encore d'évaluation

- Collaborative Practice and Carl RogersDocument22 pagesCollaborative Practice and Carl RogersDanilo Moggia100% (1)

- Russo2007 History of Cannabis and Its Preparations in Saga, Science, and SobriquetDocument35 pagesRusso2007 History of Cannabis and Its Preparations in Saga, Science, and SobriquetArnold DiehlPas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative Therapy QuotesDocument7 pagesNarrative Therapy QuotesSchecky0% (1)

- Duvall, Jim - Béres, Laura - Innovations in Narrative Therapy - Connecting Practice, Training, and Research-W. W. Norton & Company (2011)Document266 pagesDuvall, Jim - Béres, Laura - Innovations in Narrative Therapy - Connecting Practice, Training, and Research-W. W. Norton & Company (2011)Danilo Moggia100% (7)

- The Hypothesis As Dialogue: An Interview With Paolo BertrandoDocument12 pagesThe Hypothesis As Dialogue: An Interview With Paolo BertrandoFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezPas encore d'évaluation

- Collaborative Therapy Relationships and Conversations That Make A DifferenceDocument25 pagesCollaborative Therapy Relationships and Conversations That Make A Differenceisiplaya2013Pas encore d'évaluation

- 12 Characteristics of A Godly WomanDocument13 pages12 Characteristics of A Godly WomanEzekoko ChinesePas encore d'évaluation

- The Externalisation of The Problem and The Re-Authoring of Lives and Relationships by Michael WhiteDocument21 pagesThe Externalisation of The Problem and The Re-Authoring of Lives and Relationships by Michael WhiteOlena Baeva93% (15)

- Narrative Means To Transformative EndsDocument7 pagesNarrative Means To Transformative EndsRaphaël Ophidius Auf-derBrierPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review On Narrative TherapyDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Narrative Therapyc5eyjfnt100% (1)

- Systemic Therapy and The Influence of Postmodernism 2000Document8 pagesSystemic Therapy and The Influence of Postmodernism 2000macmat1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Foucault & Turn To Narrative TherapyDocument19 pagesFoucault & Turn To Narrative TherapyJuan AntonioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Milan Approach - Roots and EvolutionDocument4 pagesThe Milan Approach - Roots and EvolutionVivir Sin ViolenciaPas encore d'évaluation

- JST Chang & NylundDocument18 pagesJST Chang & Nylundab yaPas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative TherapyDocument7 pagesNarrative TherapyRashidi Hamzah100% (1)

- My Story Terapia NarrativaDocument13 pagesMy Story Terapia NarrativaVissente TapiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Systemic-Dialogical Therapy Integrates Systemic Understanding and Dialogical PracticeDocument14 pagesSystemic-Dialogical Therapy Integrates Systemic Understanding and Dialogical PracticeFelipe SotoPas encore d'évaluation

- Working With Sexual Issues in Systemic Therapy by Desa MarkovicDocument13 pagesWorking With Sexual Issues in Systemic Therapy by Desa MarkovicOlena BaevaPas encore d'évaluation

- NTRYQ1 Russell 2Document18 pagesNTRYQ1 Russell 2Melissa Zuleika Caballero CastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Karl Tom - Externalize - The - ProbDocument5 pagesKarl Tom - Externalize - The - ProbGiorgio MinuchinPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethnography Co Research and Insider Knowledges by David EpstonDocument4 pagesEthnography Co Research and Insider Knowledges by David EpstonignPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1Document20 pagesChapter 1Andreea GăveneaPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing Resilience As An EducatorDocument2 pagesDeveloping Resilience As An EducatorGodman KipngenoPas encore d'évaluation

- IntersubjectivityDocument8 pagesIntersubjectivityIan Rory Owen100% (1)

- Externalizacion en AdolecentesDocument19 pagesExternalizacion en AdolecentesVissente TapiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Identity, Agency, and Therapeutic Change: Jimena Castro Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FloridaDocument16 pagesIdentity, Agency, and Therapeutic Change: Jimena Castro Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FloridaBetzi RuizPas encore d'évaluation

- Bábterápia (Angol)Document10 pagesBábterápia (Angol)Kiss LiliPas encore d'évaluation

- The Absent But Implicit - A MapDocument14 pagesThe Absent But Implicit - A Mapsun angelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Working With Sexual Issues in Systemic Therapy by Desa Markovic PDFDocument13 pagesWorking With Sexual Issues in Systemic Therapy by Desa Markovic PDFsusannegriffinPas encore d'évaluation

- Dimensions of Majority and Minority GroupsDocument18 pagesDimensions of Majority and Minority GroupsMariana PorfírioPas encore d'évaluation

- Meehan Guilfoyle-Narrative Formulation-Pre PubDocument29 pagesMeehan Guilfoyle-Narrative Formulation-Pre PubDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Judit Hajdu - Narr Med in Restor JusticeDocument19 pagesJudit Hajdu - Narr Med in Restor JusticeSaúl Miranda RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Collaborative Relationships and Dialogic Conversation, Ideas For A Relationally Responsive PracticeDocument23 pagesCollaborative Relationships and Dialogic Conversation, Ideas For A Relationally Responsive Practiceisiplaya2013Pas encore d'évaluation

- Meme CounsellingDocument25 pagesMeme CounsellingstephaniePas encore d'évaluation

- Therapeutic Practice As Social ConstructionDocument29 pagesTherapeutic Practice As Social ConstructionA MeaningsPas encore d'évaluation

- Dimensions of Majority and Minority GroupsDocument17 pagesDimensions of Majority and Minority GroupsAfrida MasoomaPas encore d'évaluation

- CAP 1lay TheoriesDocument33 pagesCAP 1lay TheoriesMaría José VerrónPas encore d'évaluation

- NARRATIVE FAMILY THERAPYDocument28 pagesNARRATIVE FAMILY THERAPYIrish Grace DubricoPas encore d'évaluation

- Enacting Stories_ Discovering Parallels of Narrative and ExTDocument40 pagesEnacting Stories_ Discovering Parallels of Narrative and ExTViva PalavraPas encore d'évaluation

- Collaborative Inquiry Chapter 22 Gehart Tarragona Bava PDFDocument12 pagesCollaborative Inquiry Chapter 22 Gehart Tarragona Bava PDFnicolas mossoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Absent But Implicit A Map To SupportDocument13 pagesThe Absent But Implicit A Map To SupportDr Self HelpPas encore d'évaluation

- Working With Metaphor in Narrative TherapyDocument10 pagesWorking With Metaphor in Narrative TherapySidney OxboroughPas encore d'évaluation

- L7 Ray&Borer 2007Document9 pagesL7 Ray&Borer 2007Elizabeth KentPas encore d'évaluation

- Verbal Communication EssayDocument4 pagesVerbal Communication EssayafhbhgbmyPas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative Means To Transformative Ends:towards A Narrative Language For TransformationDocument7 pagesNarrative Means To Transformative Ends:towards A Narrative Language For TransformationDiana CortejasPas encore d'évaluation

- Askehave and Swales - Genre Identification and Communicative PurposeDocument18 pagesAskehave and Swales - Genre Identification and Communicative PurposeSamira OrraPas encore d'évaluation

- Fragmentation or Differentiation: Questioning The Crisis in PsychologyDocument13 pagesFragmentation or Differentiation: Questioning The Crisis in PsychologyAndrra DadyPas encore d'évaluation

- Building On Each Other's Ideas: A Social Mechanism of Progressiveness in Whole-Class Collective InquiryDocument36 pagesBuilding On Each Other's Ideas: A Social Mechanism of Progressiveness in Whole-Class Collective InquiryJaime FauréPas encore d'évaluation

- Foreign Policy AnalysisDocument22 pagesForeign Policy AnalysisNaima ZiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fragmentation or Differentiation: Questioning The Crisis in PsychologyDocument12 pagesFragmentation or Differentiation: Questioning The Crisis in Psychologyfakeusername01Pas encore d'évaluation

- Projective DrawingsDocument14 pagesProjective DrawingsLeya CallantaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unresolved Issues Socratic Questioning - Authors - VersionDocument18 pagesUnresolved Issues Socratic Questioning - Authors - VersionSakti ManPas encore d'évaluation

- Increasing Awareness of Stigmatization - Advocating The Role of OtDocument109 pagesIncreasing Awareness of Stigmatization - Advocating The Role of OtGiselle Pezoa WattsonPas encore d'évaluation

- 2024 Philosophical PsychologyDocument28 pages2024 Philosophical PsychologymarianabalbuenasanchexPas encore d'évaluation

- The Advance of Poststructuralism and Its Influence On Family TherapyDocument14 pagesThe Advance of Poststructuralism and Its Influence On Family TherapyBetzi RuizPas encore d'évaluation

- Anderson2012 Collaborative Relationships and DialogicDocument17 pagesAnderson2012 Collaborative Relationships and DialogicJosé BlázquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Inherent Self, Invented Self, Empty Self: Constructivism, Buddhism, and PsychotherapyDocument22 pagesInherent Self, Invented Self, Empty Self: Constructivism, Buddhism, and PsychotherapyNarcisPas encore d'évaluation

- ITTI - Marquis (2009)Document30 pagesITTI - Marquis (2009)Andre MarquisPas encore d'évaluation

- Creating Living Standards of Judgment FoDocument14 pagesCreating Living Standards of Judgment FoEDWIN CASTROPas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond Directive or NondirectiveDocument9 pagesBeyond Directive or NondirectiveNadiya99990100% (2)

- Core Competencies Manual PDFDocument136 pagesCore Competencies Manual PDFDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lieb 2003Document16 pagesLieb 2003Danilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hope in CBT For Anxiety PDFDocument38 pagesHope in CBT For Anxiety PDFDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ambivalence in Moral SelfDocument21 pagesAmbivalence in Moral SelfDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative Therapy, Postmodemism, Social Constructionism, and Constructivism: Discussion and DistinctionsDocument6 pagesNarrative Therapy, Postmodemism, Social Constructionism, and Constructivism: Discussion and DistinctionsDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Foucauldian Influences in NarrativeDocument22 pagesFoucauldian Influences in NarrativeJoão D C MendonçaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2007 - Tu - Et - Al - 2007 - Revisiting The Relation Between Change and Initial ValueDocument15 pages2007 - Tu - Et - Al - 2007 - Revisiting The Relation Between Change and Initial ValueDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2nd Ord Cybernetics and Enaction PerceptionDocument12 pages2nd Ord Cybernetics and Enaction PerceptionDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Quality of Life in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Narrative OverviewDocument8 pagesQuality of Life in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Narrative OverviewDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Meehan Guilfoyle-Narrative Formulation-Pre PubDocument29 pagesMeehan Guilfoyle-Narrative Formulation-Pre PubDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative Methods Primer FINAL - Version For SharingDocument31 pagesNarrative Methods Primer FINAL - Version For SharingDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Allan Clinical Supervision TitleDocument15 pagesAllan Clinical Supervision TitleDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Transcultural Differences in The Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocument1 pageTranscultural Differences in The Irritable Bowel SyndromeDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Deconstruction of Classical Social Ps ExperimentsDocument4 pagesDeconstruction of Classical Social Ps ExperimentsDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognitive Narrative PsychotherapyDocument13 pagesCognitive Narrative PsychotherapyЈован Д. РадовановићPas encore d'évaluation

- Forgiveness Social PsychologyDocument42 pagesForgiveness Social PsychologyDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Method of LevelsDocument6 pagesMethod of LevelsDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2nd Ord Cybernetics and Enaction PerceptionDocument12 pages2nd Ord Cybernetics and Enaction PerceptionDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ambivalence in Moral SelfDocument21 pagesAmbivalence in Moral SelfDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Deconstruction of Classical Social Ps ExperimentsDocument4 pagesDeconstruction of Classical Social Ps ExperimentsDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Autoetnography Narrative ResearchDocument19 pagesAutoetnography Narrative ResearchDanilo Moggia100% (1)

- Integration in Constructivist Psychotherapy: A New ProposalDocument1 pageIntegration in Constructivist Psychotherapy: A New ProposalDanilo Moggia100% (1)

- Integration in Constructivist Psychotherapy: A New ProposalDocument2 pagesIntegration in Constructivist Psychotherapy: A New ProposalDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Integratrion in Constructivist PsychotherapyDocument2 pagesIntegratrion in Constructivist PsychotherapyDanilo MoggiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nerd Gets Revenge On School BullyDocument15 pagesNerd Gets Revenge On School BullyCarmen DelurintuPas encore d'évaluation

- Act1 - StatDocument6 pagesAct1 - StatjayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Ugly TruthDocument94 pagesThe Ugly Truthgeetkumar1843% (7)

- Blackout PoetryDocument12 pagesBlackout PoetryCabbagesAndKingsMagPas encore d'évaluation

- Scattering of Scalar Waves From A Schwarzschild Black HoleDocument6 pagesScattering of Scalar Waves From A Schwarzschild Black HoleCássio MarinhoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Brief History of The ComputerDocument70 pagesA Brief History of The ComputerUjang KasepPas encore d'évaluation

- Canteen Project ReportDocument119 pagesCanteen Project ReportAbody 7337Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2018Ch85 - Pressure Controller FInal LabDocument12 pages2018Ch85 - Pressure Controller FInal LabAdeel AbbasPas encore d'évaluation

- Andrew W. Hass - Auden's O - The Loss of One's Sovereignty in The Making of Nothing-State University of New York Press (2013)Document346 pagesAndrew W. Hass - Auden's O - The Loss of One's Sovereignty in The Making of Nothing-State University of New York Press (2013)EVIP1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Commentary of Suratul JinnDocument160 pagesCommentary of Suratul JinnSaleem Bhimji100% (3)

- English Model Test 1 10Document20 pagesEnglish Model Test 1 10wahid_040Pas encore d'évaluation

- Module 10 - Passive Status KeeperDocument15 pagesModule 10 - Passive Status KeeperFaisal Saeed SaeedPas encore d'évaluation

- Project REAP-Root Cause AnalysisDocument4 pagesProject REAP-Root Cause AnalysisAIRA NINA COSICOPas encore d'évaluation

- PGFO Week 9 - Debugging in ScratchDocument13 pagesPGFO Week 9 - Debugging in ScratchThe Mountain of SantaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lt1039 - Linear Tecnology-Rs232Document13 pagesLt1039 - Linear Tecnology-Rs232Alex SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Humility in Prayer 2Document80 pagesHumility in Prayer 2Malik Saan BayramPas encore d'évaluation

- IMS 7.4 Custom Postprocessor InstallationDocument2 pagesIMS 7.4 Custom Postprocessor InstallationZixi FongPas encore d'évaluation

- 4literacy and The Politics of Education - KnoblauchDocument8 pages4literacy and The Politics of Education - KnoblauchJorge Carvalho100% (1)

- Build A Bootable BCD From Scratch With BcdeditDocument2 pagesBuild A Bootable BCD From Scratch With BcdeditNandrianina RandrianarisonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Shakespearean Sonnet: WorksheetDocument3 pagesThe Shakespearean Sonnet: WorksheetJ M McRaePas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Luptons The Emotional SelfDocument3 pagesReview of Luptons The Emotional SelfDebbie DebzPas encore d'évaluation

- The Society of Biblical LiteratureDocument25 pagesThe Society of Biblical LiteratureAngela NatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Ilp Pat Test On DbmsDocument5 pagesIlp Pat Test On DbmsVijai MoganPas encore d'évaluation

- Timeline of The Philippine Revolution FRDocument2 pagesTimeline of The Philippine Revolution FRGheoxel Kate CaldePas encore d'évaluation

- Ezer or Kinegdo?Document5 pagesEzer or Kinegdo?binhershPas encore d'évaluation

- Use of Social Media For Political Engagement: A Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesUse of Social Media For Political Engagement: A Literature ReviewCharlyn C. Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Hbsc2203 - v2 - Tools of Learning of SciencesDocument10 pagesHbsc2203 - v2 - Tools of Learning of SciencesSimon RajPas encore d'évaluation