Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Green Purchasing Strategies-Trend and Implications - 0

Transféré par

Dipesh BaralTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Green Purchasing Strategies-Trend and Implications - 0

Transféré par

Dipesh BaralDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Green Purchasing Strategies:

Trends and Implications

BY

Hokey Min and William P. Galle

IN BRIEF

Hokey Min is an Associate Professor of

Logistics and Operations Management at

Auburn University. He earned his Ph.D.

degree in management science from Ohio

State University. His research interests

include logistics, materials and purchasing

management, international operations

management, and service quality.

William Galle is Professor of Management

and Coordinator of Continuous Quality

Improvement at the University of New

Orleans. He earned his Ph.D. degree from

the University of Arkansas. Dr. Galle is

currently researching trends in electronic

purchasing.

Over the last two decades, growing concerns about ecosystem quality

have led to a renewed interest in environmentalism. Purchasing professionals should also be concerned and need to rethink purchasing

strategies which have traditionally neglected environmental impacts.

To help foster environmentally concerned purchasing strategies, this

article presents the findings of an empirical survey of NAPM members in firms with a high level of awareness and frequent applications

of green purchasing. Environmental factors are identified that may

reshape supplier selection decisions. The role of green purchasing

in reducing and eliminating waste is discussed. Also, effects of

green purchasing on packaging decisions are explored. Finally,

some important practical guidelines are suggested which may enhance

the effectiveness of regulatory compliance, pollution prevention, and

resource recovery.

BACKGROUND

apid environmental deterioration over the last few decades has

dramatically increased consumer awareness of environmental

problems. As consumers become increasingly critical of industrys

reactive environmental policies, a growing number of companies are

developing company-wide environmental programs and green (environmentally sound) products. Recognizing the increased importance of

environmental programs to market success, firms in the United States

are expected to invest more than $200 billion during the 1990s to make

their products green. 1 The Marketing Intelligence Service also

reported that the share of green products as a percentage of total new

products introduced in the first half of 1990 rose to 9.2 percent from

0.5 percent in 1985.2 Increased investment in green products alone,

however, does not guarantee a successful environmental program.

The establishment of a company-wide environmental program should

begin with source reduction of solid wastes. Examples of such wastes

Module 4

10

International Journal of Purchasing and Materials

Management Copyright August 1997, by the

National Association of Purchasing Management, Inc.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Richard Boyle of the Center for Advanced Purchasing Studies

for his assistance and support for this research. The authors also wish to thank the NAPM members

who responded to the questionnaires and provided valuable data for this research.

International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management , Summer 1997

include packaging materials, metal scrap, food

waste, yard waste, and organic waste. Among

these, packaging materials account for 30.3 percent

of the municipal waste stream, the largest single

component.3 Considering that packaging materials

represent a major source of solid waste, an effective

green packaging program is vital to the success of

the overall environmental program. Leading U.S.

companies such as Du Pont, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo,

Procter & Gamble, H.J. Heinz, and International

Paper have launched various forms of green packaging programs through the introduction of recyclable and reusable packages.4

Green packaging, in turn, cannot be totally successful without the systematic reduction of

upstream waste sources associated with purchased

materials/parts and their packaging (see Figure 1).

Bloemhof-Ruwaard, et al.,5 observed that waste and

emissions caused by the supply chain have become

the main sources of serious environmental problems including global warming and acid rain. Furthermore, the importance of the supply chain in

improving overall environmental performance has

been recognized in environmental standards such

as BS 7750 on Environmental Management Systems

and the parallel European Union (EU) regulation on

eco-management and auditing.6 Thus, one of the

most effective ways to tackle environmental problems is to focus on waste prevention and control at

the source through green purchasing. This sentiment is echoed by purchasing professionals. In a

1994 survey, purchasing managers picked environmental and regulatory costs as their second most

important economic concerns.7

Formulation of a green purchasing strategy is

not a simple matter. Green purchasing may result

in increased material cost and qualified suppliers

may be limited because of the need for non-traditional materials and parts. In light of these challenges, this research addresses the following

questions about green purchasing strategies:

1. How knowledgeable are purchasing professionals about environmental advances in

products, parts, materials, and packaging?

2. What are the most prevalent green purchasing strategies among source reduction and

waste management programs?

3. Do state and federal environmental regulations significantly influence green purchasing

efforts?

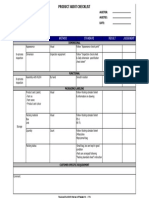

FIGURE 1

CLASSIFICATION OF GREEN PURCHASING STRATEGIES

Green Purchasing

Strategies

Source Reduction

Waste Elimination

Recycling

(On-site and

Source

Reuse

Changes and

Off-site)

Biodegrading

Control

Input Material

Low-Density

Purification and

Packaging

Substitution

Design

Green Purchasing Strategies: Trends and Implications

Nontoxic

Scrapping or

Incineration

Dumping

11

International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management , Summer 1997

4. What kinds of green packaging materials are

available?

5. How do purchasing professionals work with

suppliers to reduce upstream waste?

6. How do environmental partnerships affect

supplier evaluation and selection?

green purchasing initiatives, the current finding

implies a growing awareness of green purchasing

among purchasing professionals. Somewhat surprisingly, however, less than half of the respondents

(46.2 percent) said their firms had environmental

mission statements. This may be due, in part, to

the unavailability of defined green purchasing

strategies which can lead to more environmentally

conscious choices of supply sources.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

To help answer these questions, a survey questionnaire was developed for selected industry groups

which are heavy producers of scrap and waste

materials. These industries include chemicals (26.6

percent of the responding firms), food (12.3 percent), printing (9.8 percent), paper (9.2 percent),

oil/gas extraction (6.7 percent), textiles (3.9 percent),

furniture (3.9 percent), petroleum refineries (2.9 percent), lumber (2.5 percent), apparel (1.9 percent),

and others (20 percent). The survey was sent to a

random sample of 3,000 NAPM members employed

in those industries. From this sample, a total of 527

responses were received, a response rate of 17.6 percent. The Statistical Packages for Social Sciences

(SPSSX) was used to analyze the data.8

INFLUENCE OF GREEN PURCHASING ON

SUPPLIER SELECTION

Recent world-wide polls show that consumers are

increasingly in favor of green products.10 For example, a survey of 400 Midwestern consumers in the

United States indicated that 312 of the respondents

would be very likely or likely to switch to more

environmentally friendly food brands.11 Many firms

have viewed this heightened environmental consciousness among consumers as a great marketing

opportunity. Because purchasing is at the beginning

of the green supply chain, green marketing efforts

cannot be successful without integrating the companys environmental goals with purchasing activities. Accordingly, purchasing professionals need to

address the relationship between environmental

factors and supplier selection.

Most of the sample firms (90 percent) had more

than 100 employees; 52.7 percent had more than

500. Fifty percent employed more than four purchasing professionals. Annual purchasing volume

of most sample firms (97.4 percent) ranged from $1

million to over $1 billion. The majority were in the

$1 million to $300 million range (67.2 percent).

Finally, a majority of respondents (76.8 percent)

indicated that they were familiar with the concept

of green purchasing.

This research examined the influence of environmental factors on supplier selection strategies. As

shown in Table I, the most important influences on

supplier selection are potential liability, followed

by cost associated with the disposal of hazardous

material, and compliance with state and federal

environmental regulations. The importance of the

factors may stem from fear of liability litigation

and fines and subsequent negative publicity. For

example, the Clean Air Amendments have provided broad enforcement authority enabling the

Most of the respondents (84.4 percent) indicated

that they have participated in some form of green

purchasing initiative. In contrast with an earlier

purchasing survey9 indicating that only 40 percent

of the purchasing professionals were involved in

TABLE I

KEY FACTORS THAT AFFECT A BUYING FIRMS CHOICE OF SUPPLIERS

Factors

Average Degree of Importance1

Raw Rank

Adjusted Rank2

Potential liability for disposal of hazardous materials

1.488 (0.966)

Cost for disposal of hazardous materials

1.703 (1.073)

State environmental regulations

1.844 (1.111)

Federal environmental regulations

1.852 (1.104)

Cost of environmentally friendly goods

2.135 (1.046)

Cost of environmentally friendly packages

2.145 (1.047)

Buying firms environmental mission

2.420 (1.288)

Suppliers advances in providing environmentally friendly packages

2.640 (1.115)

Suppliers advances in developing environmentally friendly goods

2.745 (1.102)

Environmental partnership with suppliers

2.829 (1.190)

10

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations.

Scale: 5 = not at all important, 1 = extremely important

Note: The same adjusted rank indicates no statistically significant difference in means at p = 0.05.

12

Green Purchasing Strategies: Trends and Implications

International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management , Summer 1997

United States Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) to issue field citations and seek civil and

criminal penalties against polluters.12 Furthermore,

the environmental regulations in the United States

are very strict and complicated, encompassing

95,000 different state and federal environmental

protection laws and regulations. These results are

somewhat congruent with Monczka and Trents

conclusion that one of the most important future

concerns for purchasing management is the impact of

environmental regulation on purchasing activities.13

As purchasing professionals become increasingly attentive to environmental regulations, they

have begun to perform environmental compliance

audits to review applicable environmental regulations, identify new restrictions, and evaluate how

environmental initiatives help their companies

conform to evolving regulatory guidelines. More

than half (57.8 percent) of the respondents to this

survey indicated that their company had an environmental auditing program. On the other hand,

only 31.9 percent of the respondents include a suppliers environmental commitment as part of their

supplier quality assurance criteria.

THE ROLE OF GREEN PURCHASING IN

SOURCE REDUCTION

Effective source reduction strategies should reduce

the amount or change the type of waste generated

at the beginning of the supply chain through recycling, reuse, and source changes and control (see

Figure 1). Purchasing can enhance the effectiveness of a source reduction strategy in a number of

ways such as:

1. reducing the purchased volume of items that

are difficult to dispose of or are harmful to

the ecosystem

2. reducing the use of hazardous virgin materials by purchasing a higher percentage of recycled or reused content

3. requiring that suppliers minimize unnecessary packaging and use more biodegradable

or returnable packaging14

In this study, respondents were asked to indicate

the frequency of use of three strategies which

could be used to reduce the sources of upstream

waste. These results are shown in Table IIA.

in Table III, (see page 14) frequently recycled commodities are paper, cardboard, aluminum, pallets,

plastics, and ferrous metal.

Reuse

The next common strategy for source reduction is

reuse (see Table IIA). While only 37 percent of the

respondents said they either frequently or somewhat frequently utilized reuse, 67.6 percent said

their firms asked their employees to separate

reusables from other waste. One explanation for

the lack of the reuse strategy is that it requires the

use of a product or part in its same form for the

same use, but wear and tear resulting from the

previous use may make many non-durable

products or parts unreusable. As such, reuse seems

to be restricted to more durable commodities, such

as pallets, cardboards, and paper (see Table IV,

page 14). The popularity of pallets for reuse may

be attributed to their sturdier design (e.g., blockstyle) and ease of handling.16

THE ROLE OF GREEN PURCHASING IN

WASTE ELIMINATION

Waste elimination strategies may not necessarily

prevent pollution, but they can simplify waste disposal at landfills and incinerators. These strategies

include scrapping, sorting for nontoxic incineration, and biodegradable packaging. While sorting

for nontoxic incineration and biodegradable packaging are not widely used by the respondents,

nearly half (48.9 percent) either frequently or

somewhat frequently scrap or dump waste that

cannot be reclaimed. The somewhat frequent use

TABLE II A

MAJOR WASTE SOURCE REDUCTION STRATEGIES

Strategies

Average Frequency of Use1

Rank2

Recycling

1.832 (1.075)

Reuse

2.865 (1.282)

Low-density packaging

3.169 (1.278)

TABLE II B

MAJOR WASTE ELIMINATION STRATEGIES

Average Frequency

of Use1

Raw

Rank

Adjusted

Rank3

Scrapping or dumping

2.571 (1.228)

Sorting for nontoxic incineration

3.248 (1.513)

Biodegradable packaging

3.437 (1.349)

Recycling

Survey results indicate that 73.8 percent of the

respondents either frequently or somewhat frequently use recycling for source reduction. This

may be due in part to the more than 400 solid

waste and recycling laws enacted by state governments in the United States.15

Strategies

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations.

Scale: 5 = never used, 1 = frequently used

2

Note: The difference between all of the means is statistically significant at p = 0.05.

3

Note: The same adjusted rank indicates no statistically significant difference in means

at p = 0.05.

1

Furthermore, 93.8 percent of the responding

firms indicated that they asked their employees to

separate recyclables from other waste. As shown

Green Purchasing Strategies: Trends and Implications

13

International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management , Summer 1997

TABLE III

FREQUENCY OF RECYCLED COMMODITIES

Commodities

Frequency (in percent)*

Rank

Paper

16.3%

Cardboard

13.8%

Aluminum

12.5%

Pallets

11.9%

Plastic

8.1%

Ferrous metal

7.4%

Motor oil

7.1%

Non-ferrous metal

6.2%

Glass

4.7%

Wooden structure

4.0%

10

Air bubble packaging

2.9%

11

Others

2.1%

12

Corrugated foam

1.4%

13

Syringes

0.8%

14

Vinyl

0.6%

15

Graphite

0.2%

16

*Note: Frequency represents the percentage of the responding firms that recycled each commodity.

TABLE IV

FREQUENCY OF REUSED COMMODITIES

Commodities

Frequency (in percent)*

Rank

Pallets

25.8%

Cardboard

14.5%

Paper

14.3%

Air bubble packaging

9.6%

Wooden structure

5.8%

Aluminum

5.2%

Plastic

4.6%

Motor oil

4.1%

Ferrous metal

4.0%

Others

3.5%

10

Non-ferrous metal

2.9%

11

Corrugated foam

2.7%

12

Glass

2.0%

13

Syringes

0.5%

14

Vinyl

0.3%

15

Graphite

0.1%

16

*Note: Frequency represents the percentage of the responding firms that reused each

commodity.

of scrapping may be associated with the availability of investment recovery programs which assist

purchasing professionals in the most profitable

disposal of their scrap. Investment recovery programs are organized or sponsored by both profit

14

and non-profit organizations. These organizations

include the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries,

Industrial Materials Exchange (IMEX), National

Association for the Exchange of Industrial

Resources (NAEIR), Gifts In Kind America, and

the California Integrated Waste Management

Boards California Materials Exchange (CALMAX).

According to Murphree, 17 there were nearly 30

waste exchange agencies throughout the United

States in 1993 which helped purchasing professionals divert scrap otherwise destined for landfills

or incinerators. Nonetheless, waste elimination

strategies are not as frequently used as waste

source reduction strategies.

INFLUENCING FACTORS IN GREEN

PACKAGING

As discussed earlier, packaging represents over 30

percent of municipal solid waste and it is growing

in proportion. In an effort to reduce packaging

waste at landfills, much of the recent environmental

legislation around the world is directed toward

packaging. Germanys Green Dot Program of 1991

requires shippers to take full responsibility for the

disposal of transport packaging. The German law

specifies that shippers should collect, process, and

recycle 95 percent of transport packaging.18 Both the

state of Wisconsin and the city of Toronto ban the

disposal of certain types of packaging waste such as

expanded polystyrene (EPS) and wood pallets.19

Furthermore, the United Nations performanceoriented packaging requirements mandate that

buyers should know the type of hazard posed by

transport packages.20

Purchasing professionals face the challenge of

protecting items from shipping damage while

reducing wasteful, excessive, and non-recyclable

packaging. To determine how this challenge is met,

this research addressed two specific questions:

1. What factors affect the buying firms green

packaging strategy?

2. What effect does green packaging have on the

type of packaging materials selected?

As shown in Table V, the respondents indicated

that compliance with environmental packaging

legislation, package cost, and the nontoxicity and

recyclability of packages are among the most

important factors affecting green packaging. The

significance of environmental regulations to green

packaging is due to various economic incentives

such as deposits, taxes, bans, labeling, recycling,

manifests, and discharge licenses/permits. Since

most of these economic incentives tie the ultimate

cost of packaging disposal to the waste generator,

regulatory concerns are, to some degree, intertwined with cost concerns.

The second principal issue of green packaging is

the cost associated with packaging materials and

Green Purchasing Strategies: Trends and Implications

International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management , Summer 1997

TABLE V

KEY FACTORS THAT AFFECT A BUYERS GREEN PACKAGING EFFORTS

Factors

Average Degree of Importance1

Raw Rank

Adjusted Rank2

Conform to regulations on hazardous items

1.346 (0.665)

Package material cost

1.625 (0.736)

Package disposal cost

1.754 (0.867)

Nontoxic elements

1.805 (0.932)

Recyclability

1.847 (0.897)

Reusability

2.263 (1.096)

Biodegradability

2.512 (1.143)

Low-density

2.784 (1.062)

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations.

Scale: 5 = not at all important, 1 = extremely important

2

Note: The same adjusted rank indicates no statistically significant difference in means at p = 0.05.

disposal. The importance of packaging material

cost may stem from the fact that environmental

advances in packaging often require new designs

and materials and consequently increase package

material cost. For instance, the use of some innovative packages, such as high density polyethylene

pallets, moisture absorbing desiccant packets,

hydraulic pressured compact film, and regenerated cellulose film can escalate package material

cost, but increase durability, recyclability, reusability, and biodegradability.21 Package disposal cost is

another important concern in that it is constantly

rising due to shrinkages in disposal capacity (i.e.,

landfills) across the United States.

The survey asked the respondents to indicate

which types of packaging are environmentally

friendly. The most frequent responses were corrugated fiberboard cases, paper balers, and wood

crates, boxes, and baskets (see Table VI), all traditional forms of package materials. This finding can

be explained in two ways. First, 64.9 percent of the

respondents believe that green packaging does not

have to be significantly different from traditional

packaging. This implies that purchasing professionals green packaging strategy may not include

the latest technological advances in packaging

design and materials. Second, traditional packing

materials provide good product protection and yet

their material cost is low compared with more

innovative and environmentally sound packaging

such as polyethylene films.22

OBSTACLES TO EFFECTIVE GREEN

PURCHASING

Although green purchasing has become a daily

concern for many purchasing professionals, a

number of obstacles may hinder effective green

purchasing efforts. The respondents were asked to

rate the severity of several obstacles. The responses

are shown in Table VII (see page 16).

Green Purchasing Strategies: Trends and Implications

The three most serious obstacles are all based on

costs and revenues: high cost of environmental

programs, uneconomical recycling, and uneconomical reuse. This result is contradictory to Cavinatos observation that public policy in the 1990s

is likely to emphasize environmental and social

considerations, rather than economic considerations.23 This result also implies that many purchasing

professionals do not fully recognize the potential

economic benefits of green purchasing. Green purchasing programs can create economic value, such

as reduced disposal and liability costs, while conserving resources and improving the companys

public image. Nevertheless, many purchasing professionals seem to be dissuaded from green purchasing programs due in part to a misconception

that such programs are expensive to initiate

TABLE VI

TYPES OF ENVIRONMENTALLY FRIENDLY PACKAGING

Percent of Respondents

Indicating Each as

Types

Environmentally Friendly

Rank

Corrugated fiberboard cases

18.3%

Paper balers

13.2%

Wood crates, boxes, and baskets

12.1%

Palletized cardboards or foams

9.3%

4 (tie)

Multiwall paper sacks

9.3%

4 (tie)

Steel, plastic, and fiber drums

9.2%

Barrels

6.9%

Polyethylene films

5.8%

Steel, plastic pails, and wood kegs

5.6%

Plastic film bags

4.9%

Custom-built disposable woods or foams

3.4%

10

Polyvinyl chloride films

1.1%

11

Others

1.1%

12

15

International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management , Summer 1997

TABLE VII

OBSTACLES TO EFFECTIVE GREEN PURCHASING

Variables

Average Seriousness1

Raw Rank

Adjusted Rank2

High cost of environmental programs

1.832 (0.917)

Uneconomical recycling

1.964 (0.977)

Uneconomical reusing

2.028 (0.996)

Lack of management commitment

2.355 (1.201)

Lack of buyer awareness

2.453 (1.012)

Lack of supplier awareness

2.541 (0.977)

Lack of company-wide environmental standards or auditing programs

2.583 (1.190)

Loose state environmental regulation

2.987 (1.156)

Loose federal environmental regulation

3.005 (1.154)

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations.

Scale: 5 = no problem at all, 1 = very serious

Note: The same adjusted rank indicates no statistically significant difference in means at p = 0.05.

and implement. Dassapa and Maggioni24 argued

that recycled material is usually less expensive to

purchase than comparable virgin materials and

sometimes can lower capital and operating costs

for manufacturing facilities. Furthermore, firms

that participate in recycling programs often receive

tax credits and exemptions from some state governments.25 Apparently a hidden obstacle to green

purchasing is the lack of systematic methods to aid

purchasing professionals in accurately measuring

benefits and costs.

MAJOR FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS

This section summarizes some of the major issues

with green purchasing and develops practical guidelines for green-minded purchasing professionals.

First, current green purchasing strategies seem

to be reactive in that they try to avoid violations

of environmental statues, rather than embedding

environmental goals within the long-term corporate policy. The linkage between green purchasing

and supplier quality assurance is still weak.

Nonetheless, the respondents concern over environmental compliances is understandable given

the added environmental responsibilities imposed

on waste generators at the beginning of the supply

chain. The environmental compliance process is

complicated and environmental liabilities are

based on both willful and negligent violations.

Thus, neither ignorance nor simple carelessness

can free violators from serious convictions and

fines. To make matters more complex, environmental statues are often enforced by several different federal agencies and state governments under

somewhat different compliance rules.

Perhaps the best response to this situation is to

develop more aggressive, proactive environmental

audit programs. As a guideline, the following

audit process is suggested:

16

1. Identify applicable environmental statutes.

2. Develop standard checklists for environmental

compliances.

3. Organize an audit team comprised of both

internal management and outside third-party

inspectors (e.g., private contracting consultants).

4. Maintain records related to handling, storage,

use, and disposal of waste.

5. Assess the nature and degree of potential violations and liabilities.

6. Develop a corrective action plan and monitor

its progress.

Second, purchasing professionals cited recycling

as the most popular waste source reduction strategy. For this strategy to be effective, buying firms

need to specify their recycling policy involving

collection, separation, storage, transportation,

reprocessing, and remanufacturing. For example,

purchasing professionals need to determine which

items are recycled, who collects recyclables, how

recyclables are sorted, and where recyclables are

sold back or remanufactured. Such a policy should

also accompany comprehensive education and

training programs for all participants.

Third, despite world-wide legislative efforts

which enforce the progressive reduction of packaging waste, most purchasing professionals still do

not feel the urgency of pursuing innovative package

materials and design. The survey results showed

that innovative methods such as low-density and

biodegradable packaging are seldom used by purchasing professionals as an important part of green

purchasing strategy. Innovative packaging, however, is certain to increase its role in green purchasing

because a growing number of consumers are willing to buy biodegradable packages, and the United

States Congress has contemplated legislation

which mandates the use of biodegradable packages.26 In response to such changes, purchasing

professionals should consider making systematic

Green Purchasing Strategies: Trends and Implications

International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management , Summer 1997

comparisons between traditional and innovative

packaging in terms of their effects on ecosystem

quality, economic consequences, and resource

recovery. Those comparisons will require careful

cost/benefit analysis and detailed environmental

performance guidelines.

23. J. Cavinato, Reading the Regulatory Tea Leaves, Dis tribution, (January 1991), pp. 68-70.

24. V. Dassapa and C. Maggioni, Reuse and Recycling Reverse Logistics Opportunities, (Oak Brook, IL: Council of

Logistics Management, 1993).

25. Stilwell, Canty, Kopf, and Montrone, op. cit., 1991.

26. S. Selke, op. cit., 1990.

REFERENCES

1. A.O. Garvin, The 12 Commandments of Environmental

Compliance, Industrial Engineering, vol. 25, no. 9 (1993),

pp. 18-22.

2. V.N. Bhat, Green Ma rketing Begins with Green

Design, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, vol.

8, no. 4 (1993), pp. 26-31.

3. Packaging in the 90s - The Environmental Impact,

Modern Materials Handling, (June 1990), p. 54.

4. E.J. Stilwell, R.C. Canty, P.W. Kopf, and A.M. Montrone,

Packaging for the Environment: A Partnership for Progress,

(New York: Arthur D. Little, Inc., 1991).

5. J.M. Bloemhof-Ruwaard, P. van Beck, L. Hordijk, L.N.

Van Wassenhove, Interactions between Operational

Research and Environmental Management, European

Journal of Operational Research, vol. 85 (1995), pp. 229-243.

6. L. Webb, Green Purchasing: Forging a New Link in the

Supply Chain, PPI: Pulp and Paper International, vol. 36,

no. 6 (1994), pp. 52-56.

7. J. Carbone, CFC Phase-Out Spurs Green Purchasing,

Electronic Business Buyer, (July 1994), p. 91.

8. SPSSX Users Guide (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983).

9. Its Not Easy Buying Green, Purchasing, (December 16,

1993), pp. 31-32.

10. P. Winsemius and U. Guntram, Responding to the

Environmental Challenge, Business Horizon, (MarchApril 1992), pp. 12-20; L.M. Litvan, Going Green in

the 90s, Nations Business, (February 1995), pp. 30-32.

11. T. Eisenhart, Theres Gold in that Garbage!, Business

Marketing, (November 1990), pp. 20-24.

12. M.P. Last, Legally Bound to Mother Earth, N A P M

Insights, (March 1991), p. 8.

13. R.M. Monczka and R.J. Trent, Purchasing and Sourcing

Strategy: Trends and Implications (Tempe, AZ: Center for

Advanced Purchasing Studies, 1995).

14. J.R. Stock, Reverse Logistics (Oak Brook, IL.: Council of

Logistics Management, 1992).

15. State Recycling Laws Update, Year-end Edition (Riverdale,

MD: Raymond Communications, 1992).

16. J.A. Cooke, Block vs. Stringer: Which Pallet is Best,

Traffic Management, (February 1993), pp. 36-38.

17. J. Murphree, One Purchasers Trash is Anothers Treasure, NAPM Insights, (August 1993), pp. 24-26.

18. C. Boerner and K. Chilton, The Folly of Demand-side

Recycling, Environment, vol. 36, no. 1 (1994), pp. 7-32

19. T. Andel, New Ways to Take Out the Trash, Trans portation and Distribution, (May 1993), pp. 24-30.

20. T.G. Gorny, Performance-Oriented Packaging Requirements: Dont Be Unprepared, NAPM Insights, (November 1990), p. 4.

21. See for example T. Andel, The Environments Right for

a Packaging Plan, Transportation and Distribution,

(November 1993), pp. 66-74; S. Selke, Biodegradation and

Packaging, (Wiltshire, Great Britain: Pira Information

Services, 1990).

22. See for example J.J. Coyle, E.J. Bardi, and C.J. Langley,

Jr., The Management of Business Logistics, (St. Paul, MN:

West Publishing Co., 1992).

Green Purchasing Strategies: Trends and Implications

17

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Assembly and Disassembly of I.C. Engines LabDocument6 pagesAssembly and Disassembly of I.C. Engines LabDipesh Baral75% (12)

- Ex.6 - Economical Speed TestDocument3 pagesEx.6 - Economical Speed TestDipesh Baral100% (1)

- Machinist Course - Lathe Operation ManualDocument140 pagesMachinist Course - Lathe Operation Manualmerlinson1100% (16)

- Graduate Resume CV GuideDocument10 pagesGraduate Resume CV GuideOluwapeluPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Write A CV: Step by Step GuideDocument8 pagesHow To Write A CV: Step by Step GuideNauman TasaddiqPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 6Document20 pagesUnit 6A.g. VenkatPas encore d'évaluation

- Green Supply-Chain Management.a State-Ofthe-Art Literaturereview.2007.Srivastava.Document28 pagesGreen Supply-Chain Management.a State-Ofthe-Art Literaturereview.2007.Srivastava.Dipesh BaralPas encore d'évaluation

- ME05108Notes 3Document3 pagesME05108Notes 3Dipesh BaralPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Resume Format: (This Should Appear at The Top of Your Resume)Document1 pageSample Resume Format: (This Should Appear at The Top of Your Resume)Kevin Glenn Pacot LabonetePas encore d'évaluation

- ME05108Notes 4Document7 pagesME05108Notes 4Dipesh BaralPas encore d'évaluation

- ME05108Notes 5Document4 pagesME05108Notes 5Dipesh BaralPas encore d'évaluation

- ME05108Notes 5Document4 pagesME05108Notes 5Dipesh BaralPas encore d'évaluation

- Drawings Chapter 4: Computer: Introduction To CadDocument2 pagesDrawings Chapter 4: Computer: Introduction To CadLakshmi ChaitanyaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Operations Method of RFL Plastic LimitedDocument13 pagesOperations Method of RFL Plastic Limitedimranronybd60% (5)

- ExperienceDocument22 pagesExperienceHazem ElseryPas encore d'évaluation

- Standard For Mangoes (Codex Stan 184-1993) Definition of ProduceDocument4 pagesStandard For Mangoes (Codex Stan 184-1993) Definition of ProduceFranz DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- Giezelle Ros Alianza Bachelor of Technical-Vocational Teacher Education AS 8: Teaching Common Competencies in Agri-Fishery Arts Sir Jeric A. AngustiaDocument1 pageGiezelle Ros Alianza Bachelor of Technical-Vocational Teacher Education AS 8: Teaching Common Competencies in Agri-Fishery Arts Sir Jeric A. AngustiaGiezelle RosPas encore d'évaluation

- Performing Programmed Horizontal Impacts Using An Inclined Impact TesterDocument4 pagesPerforming Programmed Horizontal Impacts Using An Inclined Impact TesterMei Lee ChingPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundations of Marketing 6Th Edition Pride Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument58 pagesFoundations of Marketing 6Th Edition Pride Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFwilliamvanrqg100% (8)

- Neleo 50Document3 pagesNeleo 50Anjum ParkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Supplier Evaluation FormDocument3 pagesSupplier Evaluation FormmounirbenchammaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ajanta Pacakaging Peer Review Report 2Document3 pagesAjanta Pacakaging Peer Review Report 2Rohit RahangdalePas encore d'évaluation

- CCS Implementation Manual v2.0Document38 pagesCCS Implementation Manual v2.0AndYPas encore d'évaluation

- 43 WTCA QC Manual AC10 Add On COMPLETED EXAMPLEDocument6 pages43 WTCA QC Manual AC10 Add On COMPLETED EXAMPLEAhmed GomaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Previews-ASME AG-1 2012 PreDocument26 pagesPreviews-ASME AG-1 2012 PreFajri01Pas encore d'évaluation

- Packaging 101 - The Corrugated BoxDocument8 pagesPackaging 101 - The Corrugated Boxalex1123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Brandbook UmbroDocument47 pagesBrandbook UmbromaykelcnPas encore d'évaluation

- Pride PackagingDocument2 pagesPride Packagingrooftopsolarpower080% (1)

- Is Iso 4074 2002 PDFDocument59 pagesIs Iso 4074 2002 PDFYara NavasPas encore d'évaluation

- Decree N°239 - 02Document26 pagesDecree N°239 - 02Martk MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Process Check Item Method Standard Result Judgement: Index: Auditor: Product Code: Auditee: Lot No: Date: CustomerDocument1 pageProcess Check Item Method Standard Result Judgement: Index: Auditor: Product Code: Auditee: Lot No: Date: CustomerDuy LePas encore d'évaluation

- SuperTitan Tower Foundation Installation Manual Rev9Document92 pagesSuperTitan Tower Foundation Installation Manual Rev9Tibu NMPas encore d'évaluation

- AF - Fish Processing NC II 20151119Document43 pagesAF - Fish Processing NC II 20151119Lai Serrano100% (1)

- Organic Agriculture ProductionDocument3 pagesOrganic Agriculture Productionxanthea jumawidPas encore d'évaluation

- CM PF 201 Preliminary Inspection ReportDocument5 pagesCM PF 201 Preliminary Inspection ReportJagannath MajhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Food Value Chain - Deloitte POVDocument24 pagesGlobal Food Value Chain - Deloitte POVChib D. Elodimuor100% (1)

- Food Safety Eng Man WebDocument122 pagesFood Safety Eng Man WebYuhui XiePas encore d'évaluation

- RBI FDI Inflows Report TableDocument138 pagesRBI FDI Inflows Report TableRohitSalunkhePas encore d'évaluation

- Continental-Aero SQM RequirementsDocument15 pagesContinental-Aero SQM RequirementsMustafa AydemirPas encore d'évaluation

- Logistic Manual V13 2021 ENG 03052021Document297 pagesLogistic Manual V13 2021 ENG 03052021zebastiaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Product Restrictions and Packaging (Prep) Instructions: Revised Date: July 2022Document20 pagesProduct Restrictions and Packaging (Prep) Instructions: Revised Date: July 2022whupaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gap Analysis ISO 11138-1 2017Document16 pagesGap Analysis ISO 11138-1 2017sumanPas encore d'évaluation

- FEDEX Service Guide 2013Document179 pagesFEDEX Service Guide 2013jan012583Pas encore d'évaluation