Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Acting Techniques: Body Language Facial Expression Campy Marshall Neilan

Transféré par

Marathi CalligraphyTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Acting Techniques: Body Language Facial Expression Campy Marshall Neilan

Transféré par

Marathi CalligraphyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Acting techniques[edit]

Lillian Gish, the "First Lady of the American Cinema", was a leading star in the silent era with one of the longest careers, working from

1912 to 1987

Silent film actors emphasized body language and facial expression so that the audience could better understand what

an actor was feeling and portraying on screen. Much silent film acting is apt to strike modern-day audiences as

simplistic or campy. The melodramatic acting style was in some cases a habit actors transferred from their former stage

experience. Vaudeville was an especially popular origin for many American silent film actors.[2] The pervading presence

of stage actors in film was the cause of this outburst from director Marshall Neilan in 1917: "The sooner the stage

people who have come into pictures get out, the better for the pictures." In other cases, directors such as John Griffith

Wray required their actors to deliver larger-than-life expressions for emphasis. As early as 1914, American viewers had

begun to make known their preference for greater naturalness on screen.[16]

Silent films became less vaudevillian in the mid 1910s, as the differences between stage and screen became apparent.

Due to the work of directors such as D W Griffith, cinematography became less stage-like, and the thenrevolutionary close up allowed subtle and naturalistic acting. Lillian Gish has been called film's "first true actress" for her

work in the period, as she pioneered new film performing techniques, recognizing the crucial differences between stage

and screen acting. Directors such as Albert Capellani and Maurice Tourneur began to insist on naturalism in their films.

By the mid-1920s many American silent films had adopted a more naturalistic acting style, though not all actors and

directors accepted naturalistic, low-key acting straight away; as late as 1927, films featuring expressionistic acting

styles, such as Metropolis, were still being released. [17] Greta Garbo, who made her debut in 1926, would become

known for her naturalistic acting.

According to Anton Kaes, a silent film scholar from the University of Wisconsin, American silent cinema began to see a

shift in acting techniques between 1913 and 1921, influenced by techniques found in German silent film. This is mainly

attributed to the influx of emigrants from the Weimar Republic, "including film directors, producers, cameramen, lighting

and stage technicians, as well as actors and actresses.[18]"

Projection speed[edit]

Cinmatographe Lumire at the Institut Lumire, France. Such cameras had no audio recording devices built into the cameras.

Until the standardization of the projection speed of 24 frames per second (fps) for sound films between 1926 and 1930,

silent films were shot at variable speeds (or "frame rates") anywhere from 12 to 40 fps, depending on the year and

studio.[19] "Standard silent film speed" is often said to be 16 fps as a result of the Lumire brothers' Cinmatographe, but

industry practice varied considerably; there was no actual standard. William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, an Edison

employee, settled on the astonishingly fast 40 frames per second.[2] Additionally, cameramen of the era insisted that

their cranking technique was exactly 16 fps, but modern examination of the films shows this to be in error, that they

often cranked faster. Unless carefully shown at their intended speeds silent films can appear unnaturally fast or slow.

However, some scenes were intentionally undercranked during shooting to accelerate the actionparticularly for

comedies and action films.[19]

Slow projection of a cellulose nitrate base film carried a risk of fire, as each frame was exposed for a longer time to the

intense heat of the projection lamp; but there were other reasons to project a film at a greater pace. Often projectionists

received general instructions from the distributors on the musical director's cue sheet as to how fast particular reels or

scenes should be projected.[19] In rare instances, usually for larger productions, cue sheets produced specifically for the

projectionist provided a detailed guide to presenting the film. Theaters alsoto maximize profitsometimes varied

projection speeds depending on the time of day or popularity of a film,[20] or to fit a film into a prescribed time slot.[19]

All motion-picture film projectors require a moving shutter to block the light whilst the film is moving, otherwise the image

is smeared in the direction of the movement. However this shutter causes the image to flicker, and images with low

rates of flicker are very unpleasant to watch. Early studies by Thomas Edison for his Kinetoscope machine determined

that any rate below 46 images per second "will strain the eye."[19] and this holds true for projected images under normal

cinema conditions also. The solution adopted for the Kinetoscope was to run the film at over 40 frames/sec, but this was

expensive for film. However, by using projectors with dual- and triple-blade shutters the flicker rate is multiplied two or

three times higher than the number of film frames each frame being flashed two or three times on screen. A threeblade shutter projecting a 16 fps film will slightly surpass Edison's figure, giving the audience 48 images per second.

During the silent era projectors were commonly fitted with 3-bladed shutters. Since the introduction of sound with its 24

frame/sec standard speed 2-bladed shutters have become the norm for 35 mm cinema projectors, though three-bladed

shutters have remained standard on 16 mm and 8 mm projectors which are frequently used to project amateur footage

shot at 16 or 18 frames/sec. A 35 mm film frame rate of 24 fps translates to a film speed of 456 millimetres (18.0 in) per

second.[21] One 1,000-foot (300 m) reel requires 11 minutes and 7 seconds to be projected at 24 fps, while a 16 fps

projection of the same reel would take 16 minutes and 40 seconds, or 304 millimetres (12.0 in) per second.[19]

In the 1950s, many telecine conversions of silent films at grossly incorrect frame rates for broadcast television may have

alienated viewers.[22] Film speed is often a vexed issue among scholars and film buffs in the presentation of silents

today, especially when it comes to DVD releases of restored films; the 2002 restoration of Metropolis (Germany, 1927)

may be the most fiercely debated example.[citation needed]

Tinting[edit]

Main

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Acting and Stage Terminology Vocabulary ListDocument3 pagesActing and Stage Terminology Vocabulary Listrsvp2kPas encore d'évaluation

- Actor Training and Emotions - Finding A BalanceDocument317 pagesActor Training and Emotions - Finding A Balanceعامر جدونPas encore d'évaluation

- The Authentic Actor Sample PDFDocument51 pagesThe Authentic Actor Sample PDFkenlee1336100% (1)

- The Art of Directing Actors 25 PagesDocument25 pagesThe Art of Directing Actors 25 PagesErnest Goodman100% (2)

- 9 Ws of ActingDocument7 pages9 Ws of ActingNihar KamblePas encore d'évaluation

- Tips For Student ActorsDocument2 pagesTips For Student ActorsKatie Norwood AlleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Playwriting UnitDocument11 pagesPlaywriting Unitapi-352760849Pas encore d'évaluation

- ActingDocument29 pagesActingTaylor RigginsPas encore d'évaluation

- Wright, 8 Acting TechniquesDocument2 pagesWright, 8 Acting TechniquesTR119Pas encore d'évaluation

- About The Meisner Technique For ActorsDocument1 pageAbout The Meisner Technique For ActorsTeresa Cheung actressPas encore d'évaluation

- 12 Steps To Prepare Your Monologue PDFDocument4 pages12 Steps To Prepare Your Monologue PDFThandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Improvisation GamesDocument6 pagesImprovisation GamesViorel GaitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Character BuildingDocument6 pagesCharacter BuildingMarga CrisostomoPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Shurtleff's 12 Guideposts:: A Roadmap To Creating Honest, Truthful Behavior in An Audition SettingDocument25 pagesMichael Shurtleff's 12 Guideposts:: A Roadmap To Creating Honest, Truthful Behavior in An Audition SettingJennifer Mitchell100% (1)

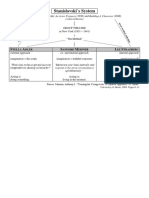

- The Stanislavski System For ActorsDocument35 pagesThe Stanislavski System For ActorsTadele Molla ታደለ ሞላPas encore d'évaluation

- Books and Resources For The ActorDocument2 pagesBooks and Resources For The ActoramarghitoaieiPas encore d'évaluation

- You Are The Reason PDFDocument1 pageYou Are The Reason PDFLachlan CourtPas encore d'évaluation

- Intro To Acting - Sixteen Keys To CharacterizationDocument4 pagesIntro To Acting - Sixteen Keys To CharacterizationKogunPas encore d'évaluation

- Acting Presentation On StellaDocument7 pagesActing Presentation On Stellaapi-463306740Pas encore d'évaluation

- Actors On ActingDocument14 pagesActors On ActingBriareusPas encore d'évaluation

- The Actor in YouDocument9 pagesThe Actor in YouIonut IvanovPas encore d'évaluation

- The New Business of Acting: How to Build a Career in a Changing LandscapeD'EverandThe New Business of Acting: How to Build a Career in a Changing LandscapeÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (2)

- ACTING General HandoutDocument4 pagesACTING General HandoutNagarajuNoolaPas encore d'évaluation

- DRAMA CLUB Chapter 4: Script AnalysisDocument9 pagesDRAMA CLUB Chapter 4: Script AnalysisVagabond LuxuriousPas encore d'évaluation

- StanislávskiDocument18 pagesStanislávskiina_neckel1186100% (1)

- Guide To Self Taping Success by Mark Westbrook Acting Coach ScotlandDocument29 pagesGuide To Self Taping Success by Mark Westbrook Acting Coach ScotlandОля Мовчун100% (1)

- Meditation For AddictionDocument2 pagesMeditation For AddictionharryPas encore d'évaluation

- Pda Teachers GuideDocument2 pagesPda Teachers Guidepeasyeasy100% (2)

- Nina Foch Course Guide PDFDocument18 pagesNina Foch Course Guide PDFVirginia MichailPas encore d'évaluation

- Six Acting Exercises-FinalDocument6 pagesSix Acting Exercises-Finalsujit44Pas encore d'évaluation

- Actioning & Blocking AssignmentDocument8 pagesActioning & Blocking AssignmentAllison McPherson TitusPas encore d'évaluation

- Meisner PDFDocument246 pagesMeisner PDFasslii_83100% (1)

- Script Analysis NotesDocument29 pagesScript Analysis NotesBrian IrelandPas encore d'évaluation

- Diploma in Film ActingDocument6 pagesDiploma in Film ActingGaikwad KishorPas encore d'évaluation

- Principles of ActingDocument15 pagesPrinciples of Actingmlbranham2753100% (1)

- 2 2 Year 7 Drama Lesson Plan 2 Week 7Document7 pages2 2 Year 7 Drama Lesson Plan 2 Week 7api-229273655100% (1)

- Stanislavski TechniquesDocument2 pagesStanislavski Techniquesapi-509765058Pas encore d'évaluation

- Advanced Acting Workshop (Being and Doing)Document43 pagesAdvanced Acting Workshop (Being and Doing)Fernan Fangon TadeoPas encore d'évaluation

- Director Actor Coach: Solutions for Director/Actor ChallengesD'EverandDirector Actor Coach: Solutions for Director/Actor ChallengesPas encore d'évaluation

- DEE CANNONS Hand Out On Character Building and AnalysisDocument7 pagesDEE CANNONS Hand Out On Character Building and AnalysisCatherine DemonteverdePas encore d'évaluation

- Acting II 17 SyllabusDocument8 pagesActing II 17 SyllabusJulia BakerPas encore d'évaluation

- Stanislavski Method HandoutDocument2 pagesStanislavski Method HandoutJustynaPas encore d'évaluation

- Acting NotesDocument19 pagesActing NotesTashuYadav100% (1)

- Playing Objectives: by Rena Cook. DRAMATICS. November 1994Document4 pagesPlaying Objectives: by Rena Cook. DRAMATICS. November 1994FRANCISCO CARRIZALES VERDUGOPas encore d'évaluation

- Theatre Semester ExamDocument4 pagesTheatre Semester ExamAutumnPas encore d'évaluation

- Kampfgruppe KerscherDocument6 pagesKampfgruppe KerscherarkhoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Using The Stanislavski Method To Create A PerformanceDocument32 pagesUsing The Stanislavski Method To Create A PerformanceAlexSantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Blueprint: PREPARATION For First Read: 2 Hours of No Interruption - Phones Off!!!Document7 pagesBlueprint: PREPARATION For First Read: 2 Hours of No Interruption - Phones Off!!!TeneishaCPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Vocal Exercises.Document2 pagesList of Vocal Exercises.RupeshBavisker0% (2)

- StanislavskiDocument4 pagesStanislavskiIrma MuminovićPas encore d'évaluation

- The Persisting VisionDocument12 pagesThe Persisting VisionKiawxoxitl Belinda CornejoPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus Directing II RevDocument5 pagesSyllabus Directing II RevEricZavadskyPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 6 Bone Tissue 2304Document37 pagesChapter 6 Bone Tissue 2304Sav Oli100% (1)

- Laban Advanced Characterization PDFDocument8 pagesLaban Advanced Characterization PDFKatie Norwood AlleyPas encore d'évaluation

- 5g-core-guide-building-a-new-world Переход от лте к 5г английскийDocument13 pages5g-core-guide-building-a-new-world Переход от лте к 5г английскийmashaPas encore d'évaluation

- Manalili v. CA PDFDocument3 pagesManalili v. CA PDFKJPL_1987100% (1)

- Verb To Be ExerciseDocument6 pagesVerb To Be Exercisejhon jairo tarapues cuaycalPas encore d'évaluation

- Acting NotesDocument3 pagesActing Notesapi-676894540% (1)

- Suppressing Acting Phobia S: General Psychology For ActingDocument26 pagesSuppressing Acting Phobia S: General Psychology For ActingmxtimsPas encore d'évaluation

- Composition Fall05Document6 pagesComposition Fall05Juciara NascimentoPas encore d'évaluation

- Mindmap - Varieties of The MethodDocument1 pageMindmap - Varieties of The MethodJanetDoePas encore d'évaluation

- Working With ActorsDocument21 pagesWorking With ActorsJoel BrandãoPas encore d'évaluation

- 58 Explore Identity Through DramaDocument20 pages58 Explore Identity Through DramaSisim24Pas encore d'évaluation

- Only Casting Name Only AprilDocument9 pagesOnly Casting Name Only AprilAna TalosPas encore d'évaluation

- On Camera: A Lesson in Film Acting For Students of TheatreDocument8 pagesOn Camera: A Lesson in Film Acting For Students of TheatreRahul MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Stella Adler ResearchDocument1 pageStella Adler Researchapi-568417403Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anne Bogart - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument7 pagesAnne Bogart - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediamauch25Pas encore d'évaluation

- ViewsDocument1 pageViewsMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- JDisability OutreachDocument1 pageJDisability OutreachMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- Arly Life and EducationDocument2 pagesArly Life and EducationMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- Publications: Popular BooksDocument2 pagesPublications: Popular BooksMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- Marriages: Jane WildeDocument1 pageMarriages: Jane WildeMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- In 2007 Hawking and His DaughterDocument1 pageIn 2007 Hawking and His DaughterMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- HIn His WorkDocument2 pagesHIn His WorkMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- See Also: Bibcode DoiDocument1 pageSee Also: Bibcode DoiMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- EthodsDocument2 pagesEthodsMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- Hawking Did Not Rule Out The Existence of A CreatorDocument1 pageHawking Did Not Rule Out The Existence of A CreatorMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- Principles and Terminology PDFDocument2 pagesPrinciples and Terminology PDFMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- Illnesses Portrayed: Gentleman's MagazineDocument1 pageIllnesses Portrayed: Gentleman's MagazineMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- World Health OrganizationDocument2 pagesWorld Health OrganizationMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- Principles and Terminology PDFDocument2 pagesPrinciples and Terminology PDFMarathi CalligraphyPas encore d'évaluation

- Jewish Standard, September 16, 2016Document72 pagesJewish Standard, September 16, 2016New Jersey Jewish StandardPas encore d'évaluation

- Oral Oncology: Jingyi Liu, Yixiang DuanDocument9 pagesOral Oncology: Jingyi Liu, Yixiang DuanSabiran GibranPas encore d'évaluation

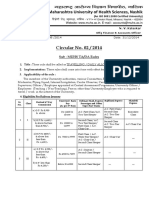

- Circular No 02 2014 TA DA 010115 PDFDocument10 pagesCircular No 02 2014 TA DA 010115 PDFsachin sonawane100% (1)

- Precertification Worksheet: LEED v4.1 BD+C - PrecertificationDocument62 pagesPrecertification Worksheet: LEED v4.1 BD+C - PrecertificationLipi AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Simplified Electronic Design of The Function : ARMTH Start & Stop SystemDocument6 pagesSimplified Electronic Design of The Function : ARMTH Start & Stop SystembadrPas encore d'évaluation

- Research PaperDocument9 pagesResearch PaperMegha BoranaPas encore d'évaluation

- Queen of Hearts Rules - FinalDocument3 pagesQueen of Hearts Rules - FinalAudrey ErwinPas encore d'évaluation

- Chemistry InvestigatoryDocument16 pagesChemistry InvestigatoryVedant LadhePas encore d'évaluation

- Advanced Financial Accounting and Reporting Accounting For PartnershipDocument6 pagesAdvanced Financial Accounting and Reporting Accounting For PartnershipMaria BeatricePas encore d'évaluation

- Intro To Law CasesDocument23 pagesIntro To Law Casesharuhime08Pas encore d'évaluation

- Product Training OutlineDocument3 pagesProduct Training OutlineDindin KamaludinPas encore d'évaluation

- 978-1119504306 Financial Accounting - 4thDocument4 pages978-1119504306 Financial Accounting - 4thtaupaypayPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment File - Group PresentationDocument13 pagesAssignment File - Group PresentationSAI NARASIMHULUPas encore d'évaluation

- Durst Caldera: Application GuideDocument70 pagesDurst Caldera: Application GuideClaudio BasconiPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Interior Architects in Kolkata PDF DownloadDocument1 pageBest Interior Architects in Kolkata PDF DownloadArsh KrishPas encore d'évaluation

- PropertycasesforfinalsDocument40 pagesPropertycasesforfinalsRyan Christian LuposPas encore d'évaluation

- Imc Case - Group 3Document5 pagesImc Case - Group 3Shubham Jakhmola100% (3)

- 1b SPC PL Metomotyl 10 MG Chew Tab Final CleanDocument16 pages1b SPC PL Metomotyl 10 MG Chew Tab Final CleanPhuong Anh BuiPas encore d'évaluation

- Fort - Fts - The Teacher and ¿Mommy Zarry AdaptaciónDocument90 pagesFort - Fts - The Teacher and ¿Mommy Zarry AdaptaciónEvelin PalenciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cat Hydo 10wDocument4 pagesCat Hydo 10wWilbort Encomenderos RuizPas encore d'évaluation

- ENTRAPRENEURSHIPDocument29 pagesENTRAPRENEURSHIPTanmay Mukherjee100% (1)

- Phylogenetic Tree: GlossaryDocument7 pagesPhylogenetic Tree: GlossarySab ka bada FanPas encore d'évaluation