Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Lisovchiki V Moskovii 1607 1616

Transféré par

caracallaxTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Lisovchiki V Moskovii 1607 1616

Transféré par

caracallaxDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

:

Brian L. Davies,

Prof. of History,

University of Texas at San Antonio (USA)

THE LISOVCHIKI IN MUSCOVY, 16071616

An important new study by David Parrott argues that historians assumption that mercenary forces must have been less reliable (costlier, more corrupt and inefficient) than state-recruited and state-administered armies has led

them to underestimate the importance of private military enterprise in European

warfare in the 1590s1630s. Parrott points out that even the Swedish army of

Gustav II Adolf could not rely entirely on Swedish canton-raised militia, so

that by 1629 Gustav II Adolf had to take about 16 000 mercenaries into his

army, some of them troops released from service of bankrupt Denmark, many

of them men newly raised on contract by German and Scottish enterprisers

(Parrott D. The Business of War: Military Enterprise and Military Revolution in

Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. P. 118,

126). Reliance on hired troops was common further east in Europe, too. The

emergency confronting Muscovys Tsar Vasilii Shuiskii forced him to employ

several thousand Swedish-raised mercenaries, and there was a long tradition of

royal resort to hired troops in Poland-Lithuania, where restrictions on the use of

the pospolite ruszenie and the budget and size of the kings Wojsko kwarciane

had pushed the last two Jagiellonian kings and King Stefan Bathory to hire

large numbers of foreign mercenaries for short periods. A factor further promoting military enterprise was the frequency of private military adventures that did

not have the blessing of any legitimate monarch, such as the Magnate Wars in

Moldavia and the involvement of Polish, Lithuanian, and Ukrainian magnates

in the First and Second Dmitriads in Muscovy.

One of the most interesting private forces in the Time of Troubles were the

Lisovchiki (Lisowczycy). They were formed in 1607 from mutinous PolishLithuanian troops outlawed by King Sigismund III after the Rokosz, and led

into Muscovy by their commander Alexander Lisowski, who augmented them

with cossack volunteers and renegade Muscovite servicemen and brought them

into the service of False Dmitrii II. The Lisovchiki participated in most of the

71

major battles of the period of the Second Dmitriad, including the long siege

of Troitse-Sergeev Monastery. Lisowski then obtained pardon and brought

his regiment them over to King Sigismund III in 1610. From 1613 to 1616

the Lisovchiki conducted daring and devastating flying raids across Muscovy.

Polish historians have been very interested in the Lisovchiki from 1843, when

Maurycy Dzieduszycki devoted a two-volume study to them; they were used in

the construction of Polish Sarmatist ideology, and they have been romanticized

in Polish historical painting (Jozef Brandt) and popular literature (Ossendowski,

Sujkowski, Korkozowicz). Rembrandts painting The Polish Rider is said to be

a portrait of a Lisovchik.

The founder and first commander of the Lisovchiki, Alexander Josef

Janowicz Lisowski, was born near Vilnius sometime between 1575 and 1580.

His forebears had emigrated from Ducal Prussia to Zmudz. The Lisowskis were

middling szlachta but had some important political connections in Lithuania and

Poland: Alexanders brother Szczesny was marszalek dworu to Cardinal Jerzy

Radziwill, and his brother Krzysztof was a dworzanin in the service of King

Sigismund August (Dzieduszycki M. Krotki rys dziejw i spraw Lisowczykov.

T. I. Lww, 1843. S. 14; Tyszkowski K. Aleksander Lisowski i jego zagony na

Moskwe // Przeglad Historyczno-Wojskowy 1932. Vol. 5. Nr. 1. S. 2; Wisner H.

Lisowczycy. Warsaw: Ksiazka i Wiedza, 1976. S. 22).

Aleksandr Lisowskis first military service was in Moldavia in 1599, during Chancellor Jan Zamoyskis campaign to install Ieremia Movila as puppet hospodar of Moldavia. Lisowski began as a simple soldier in the private

army of Jan Potocki, starosta of Kamieniec; in 1600 he fought at the battle

of Teleajan, Zamoyskis great victory over Prince Mihei Viteazul (Wisner H.

Lisowczycy. S. 23; Dzieduszycki M. Krotki rys T. I. S. 1719). The 1593

1617 Magnate Wars in Moldavia were not only contemporaneous with much

of the Time of Troubles in Muscovy; they provided some important precedents

for Polish intervention in the latter. The Magnate Wars offered an excuse for

sejmik-organized cavalry choragwie to break rules forbidding campaigning

abroad; they were waged contrary to the interests of King Sigsimund III, fought

by the private armies of magnate adventurers (the Potockis, Koreckis, and

Vyshnevetskys, with whom the Movila clan was allied by marriage); and they

revealed the tensions between szlachta forces and Ukrainian and Zaporozhian

cossacks, the latters interest in continuing fighting against the Tatars eventually

aligning them with Viteazul and thereby threatening to embroil Poland in war

with the Turks. To prevent further cossack interference with Polish operations

72

in Moldavia Zamojski eventually ordered Field Hetman Stanislaw Zolkiewski

and the Ukrainian magnate Kirik Ruzhynsky to campaign in Ukraine to crush

the armies of Nalivaiko and Loboda (Semenova L. E. Kniazhestva Valakhiia

i Moldaviia konets XIV nachalo XIX v. Moskva: Indrik, 2006. S. 171173;

Hrushevsky M. History of Ukraine-Rus. T. 7: The Cossack Age to 1625. Trans.

Bohdan Struminski. Edmonton and Toronto: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian

Studies, 1999. P. 166.)

In 1604 the newly-crowned king of Sweden, Charles X, challenged

Sigismund III Wasa by invading Livonia. Lisowski was among the Polish

Crown officers in Livonia joining their troops in confederatio and mutinying over pay arrears. The mutineers proceeded to despoil Crown and magnate

estates in Livonia and Lithuania in compensation. In a letter of 10 December

1604 Lithuanian Field Hetman Jan Karol Chodkiewicz denounced Lisowski

as a godless man and a rebel. Lisowski was sentenced to deprivation of

szlachta privileges and banishment from the Commonwealth. But instead of

emigrating he joined the Zebrzydowski Rebellion against the King (also called

the Rokosz, 16051607). In the Rokosz he joined the regiment of his patron

Janusz Radziwill and fought at the Battle of Guzow (July 5 1607) as the rotmistrz of a choragiew of mounted cossacks (Wisner H. Lisowczycy. S. 2733;

Grabowski R. Guzw 5 VII 1607. Zabrze: Wydawnictwo Inforteditions, 2005.

S. 78). The Rokoszanie were soundly defeated at Guzow, but the King found

it advisable to complete the suppression of the Rokosz by offering amnesty

to the rebellions most important leaders. Such amnesty was not extended to

Lisowski, however, because of his previous involvement in mutiny in Livonia.

After Guzow Lisowski took about a hundred men and crossed the frontier to

Starodub.

A continuing controversy in the historiography of the Troubles is the question of whether the attachment of several Polish, Lithuanian, and Ukrainian

colonels to the new army of False Dmitrii II in 1607 represented a camouflaged military intervention by King Sigismund III, or represented private initiatives undertaken by certain magnates without the kings approval. Jarema

Maciszewski placed this question at the center of his famous 1968 study, and

Igor Olegovich Tiumentsev has recently re-examined it through a close analysis

of the diary and papers of Jan Sapieha, Hetman of False Dmitrii IIs hired troops

(Maciszewski J. Polska a Moskwa 16031618. Opinie i stanowiska szlachty

polskiej. Warsaw: Panstwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1968. S. 3738, 5051,

7475, 112113, 116167; Tiumentsev I. O. 1) Inozemnye soldaty na sluzhbe

Lzhedmitriiu II, 1607 nachalo 1610 gg. // Inozemtsy v Rossii v XVXVII vekakh.

73

Sbornik materialov konferentsiia 20022004 gg. Ed. A. K. Levykin. Moskva:

Drevnekhranilishche, 2006. S. 270271, 283; 2) Smutnoe vremia v Rossii

nachala XVII stoletiia. Dvizhenie Lzhedmitriia II. Moskva: Nauka, 2008.

S. 92127, 144, 148, 151152, 154 passim.). Tiumentsevs study of the army

and administration of False Dmitrii II is the most thorough yet produced. He

finds that most of the hired troops first assembling under False Dmitrii IIs banner at Starodub in 1607 were Belarusian and Ukrainian szlachta organized in

companies of petyhorcy (Circassian-style armored lancers); that some of them

were Rokoszanie, but many not; that the movement of Rokosz veterans into

Muscovy was not encouraged by the King, but strongly forbidden by him; that

their colonels and hetmans, including Jan Sapieha, were not operating under the

secret instruction of the king or Chancellor Lew Sapieha; that the hired troops

brought over to False Dmitrii II by Jan Sapieha in early 1608 were mostly

Lithuanian and Belarusian szlachta who had served under Chodkiewicz in

Livonia and joined in the Confederatio over pay arrears; and that the King

strongly disapproved of these adventurers because he saw their involvement

in Muscovy as making the pacification of the Rokosz all the more difficult and

pulling Muscovy into his war with Sweden.

A summary of Lisowskis role in the army of False Dmitrii II shows that

he arrived sometime before November 1607 with a few hundred men; that

he showed himself of value in recruiting to False Dmitrii IIs veterans of the

now-dispersed Bolotnikov movement, especially in Seversk region, as well as

cossacks (some Zaporozhian and Don Host cossacks, some Host-unaffiliated

aspirant cossacks from Ukraine and southern Muscovy); that his regiment of

Lisovchiki comprised a few companies of husarz lancers and petihorcy but a

larger contingent of cossacks, bringing its maximum strength to five or six thousand men in August 1608; that in the scheme of the de facto division of command authority among Ruzhynsky, Zarutsky, and Jan Sapieha, the Lisovchiki

generally served under Sapieha, but separated from him after the first siege of

Troitse-Sergeev monastery was lifted. The Lisovchiki participated in several

of the major battles against the armies of Vasilii Shuiskii (Bolkhov, Karachev,

Briansk, Rakhmantsevo, Tver, etc.) and played a leading role in extending the

Tushinite movement towards Riazan, Kolomna, Iaroslavl, and the Volga. Over

time, however, Lisowski reduced his infantry contingents and artillery in order

to maximize his mobility, and this made it more difficult for him to contribute

to protracted sieges. The Lisovchiki did participate intermittently in the siege

of Troitse-Sergeev Monastery, which long remained an important Tushinite

objective not only because of the reputed wealth of its treasury but because

74

monastery estates offered mercenary companies better prospects for forage

and kormlenie. A sign of Lisowskis frustration at the interminable TroitseSergeev siege was his response to the death of his brother beneath its walls: he

massacred 202 prisoners taken from a munitions train trying to reinforce the

monastery, in response to which the monasterys defenders executed an equal

number of their own prisoners atop their fortress walls. Lisowski ruthlessly

suppressed an anti-Tushinite rebellion in Iaroslavl; Conrad Bussow describes

Lisowski as then pushing deeper into the interior, killing and exterminating

all who were encountered on his path: men, women children, dvoriane, townsmen, and peasants (Bussow C. Moskovskaia khronika Konrada Bussova //

Smuta v Moskovskom gosudarstve. Rossiia nachala XVII stoletiia v zapiskakh

sovremennikov. Ed. A. I. Pliguzov and I. A. Tikhoniuk. Moskva: Sovremennik,

1989. S. 350, 355; Budzilo J. Istoriia lozhnogo Dmitriia (iz dnevnika Budily) //

Pamiatniki smutnogo vremeni: Tushinskii vor. Lichnost, okruzhenie, vremia.

Dokumenty i materialy. Ed. V. I. Kuznetsov and I. P. Kulakova. Moskva: Izd.

Moskovskogo universiteta, 2001. S. 220221). In 1610 Lisowski gave the

commune of Pskov military assistance against de la Gardies Swedes, but his

foraging and kormlenie exaction around Pskov so alarmed the Pskovichi they

decided not to admit his regiment within their walls. The Lisovchiki then settled

in at Voronach to feed (Budzilo J. Istoriia lozhnogo Dmitriia S. 223, 287, 290).

Lisowski spent the winter of 16091610 at Voronach. His Russians and

cossacks having deserted him, he decided to march on Krasnoe with a handful of Lisovchiki (and 800 English and Irish mercenaries he had convinced to

defect from de la Gardie), hold Krasnoe for King Sigismund III, and bargain for

it the Kings pardon for his role in the Livonian mutiny. Having seized Krasnoe,

he got Adam Talosz, kasztelan of Zmudz, to intervene and convince the King

and Chancellor Lew Sapieha to pardon him. He also received a reward of 200

gold pieces and permission to take service under Chodkiewicz and raise a new

regiment of 1000 horse without pay, to be remunerated solely by plunder.

This regiment soon rose to 2000 horse. (Bussow C. Moskovskaia khronika

S. 358; Tyszkowski K. Aleksander Lisowski S. 8; Wisner H. Lisowczycy. S. 39).

After Hetman Chodkiewiczs withdrawal from Moscow in August 1612

most Polish operations in Muscovy took the form of independently undertaken

raids by particular colonels, including Lisowski. In 1613 Lisowski raided the

districts of Suzdal, Kostroma, Iaroslavl, Pereiaslavl-Riazan, Tula, Serpukhov,

and Aleksin, and then returned to his base at Krasnoe. In 1614 the Lisovchiki

made a successful sortie on behalf of Andrej Sapiehas force besieged at

Smolensk. For his 1615 campaign Lisowski, now based at Mogilev, issued

75

a call to volunteers from across the Commonwealth to join his regiment without pay and campaign in Muscovy in support of Hetman Chodkiewicz. When

he started this campaign in May he had just 600 horse, but his pulk increased

to over 2000 men by September. That year Lisowskis campaign again took

the form of a flying raid across a vast distance, starting from Briansk, circling

through Viazma, Rzhev, Tver and nearly as far north as Sol Galitskaia before

turning south through Shuiia, Suzdal, Kolomna, and Tula and dashing west

back to Seversk. Once again his strategy focused on burning towns, plundering monasteries, and moving fast enough to avoid interception by Dmitrii

Pozharskii and other Muscovite commanders (Tyszkowski K. 1) Aleksander

Lisowski S. 1426; 2) Materialy do zycoriusa Aleksandru Lisowskiego //

Przeglad Historyczno-Wojskowy. Vol. 5. Nr. 1. 1932. S. 101102; Wisner H.

Lisowczycy. S. 4264). These raids may have been inspired by the success

of Krzysztof Radziwills 1581 corps volante expedition, which covered over

1400 kilometers and nearly captured Ivan IV at Staritsa (Kupisz D. The PolishLithuanian Army in the Reign of King Stefan Bathory // Warfare in Eastern

Europe, 15001800. Ed. Brian Davies. Leiden and Boston: EJ Brill, 2012.

P. 8890). Lisowski was preparing another campaign from Starodub when he

fell from his horse and died of a stroke on 11 October 1616.

His regiment continued under his name, and the Lisovchiki actually

achieved their greatest fame in Polish historiography and popular culture for

operations they conducted after his death, when they were under the command

of Stanislaw Czaplinski and then Walenty Rogawski. After 1617 the Lisovchiki

withdrew from Muscovy and took station at Brailov in Podolia. In 1619 and

1620 they took hire under Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand II, who used them in

Hungary against Bethlen Gabor, as a counterweight to Gabors hussars; they

also raided in Moravia, where they killed Lutheran noblemen and pastors. Their

service with the Emperor was permitted by King Sigismund III because this was

a way to honor his obligations to the Emperor without committing to a full-scale

intervention by Polish Crown forces and thereby risking war with the Turks; it

also had the advantage of removing the Lisovchiki from Commonwealth soil

(Gajecky G., Baran A. The Cossacks in the Thirty Years War. Vol. I. Rome:

PP. Basiliani, 1983. P. 29, 30, 32, 40). After Zolkiewskis disastrous defeat by

the Turks at Cecora in 1620 the Emperor released the Lisovchiki from service

so they could return to the Commonwealths Podolian frontier and join the

forces of Chodkiewicz and Sahaidaczny in their great stand against the Turks at

Khotin. Ten companies of Lisovchik I about 1200 horse fought at Khotin

76

in 1621. (Podhorodecki L. Chocim 1621. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Obrony

Narodowej, 1988. S. 57, 95; Dzieduszycki M. Krotki rys T. II. S. 9, 32).

In 1624 Stanislaw Lubomirski, Palatine of Ruthenia, negotiated with

Emperor Ferdinand II to send several thousand hired cossacks and Lisovchiki

into the Emperors service in Silesia, but by then King Sigismund III and

the Sejm had lost all patience with the tumultuous passages of Lisovchiki,

and their Constitution of 1624 abolished the Lisovchik formation. Veteran

Lisovchiki did participate in the 1624 Silesian campaign, but as troops in a

special cossack corps under Polish Crown officers. Other former Lisovchiki

entered the private detachments of Commonwealth magnates, and many emigrated to the Zaporozhian Sich and participated in rebellions that had to be put

down by Crown Hetman Stanislaw Koniecpolski. (Gajecky G., Baran A. The

Cossacks Vol. II. P. 28, 72).

Key words: Time of Troubles, Lisovchiki, Cossacks

77

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Book TurmericDocument14 pagesBook Turmericarvind3041990100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Filehost - CIA - Mind Control Techniques - (Ebook 197602 .TXT) (TEC@NZ)Document52 pagesFilehost - CIA - Mind Control Techniques - (Ebook 197602 .TXT) (TEC@NZ)razvan_9100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- 500 Great Military Leaders PDFDocument881 pages500 Great Military Leaders PDFcaracallax100% (1)

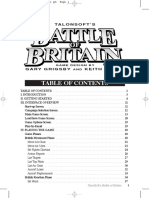

- Battle of Britain ManualDocument144 pagesBattle of Britain ManualcaracallaxPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Meditation For AddictionDocument2 pagesMeditation For AddictionharryPas encore d'évaluation

- Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists PDFDocument49 pagesRoot, Prefix, and Suffix Lists PDFLara AtosPas encore d'évaluation

- Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions - ExcerptsDocument39 pagesConcordia: The Lutheran Confessions - ExcerptsConcordia Publishing House28% (25)

- Hanumaan Bajrang Baan by JDocument104 pagesHanumaan Bajrang Baan by JAnonymous R8qkzgPas encore d'évaluation

- Kumar-2011-In Vitro Plant Propagation A ReviewDocument13 pagesKumar-2011-In Vitro Plant Propagation A ReviewJuanmanuelPas encore d'évaluation

- Gregory Napoleons ItalyDocument243 pagesGregory Napoleons ItalycaracallaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Economics and Agricultural EconomicsDocument28 pagesEconomics and Agricultural EconomicsM Hossain AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Pea RubricDocument4 pagesPea Rubricapi-297637167Pas encore d'évaluation

- Stilicho, The Rise of The Magister Utriusque Militiae and The Path To Irrelevancy of The Position of Western EmperorDocument93 pagesStilicho, The Rise of The Magister Utriusque Militiae and The Path To Irrelevancy of The Position of Western EmperorcaracallaxPas encore d'évaluation

- The Colors of The Stars: Thor Olson Management Graphics Inc. Minneapolis, MNDocument10 pagesThe Colors of The Stars: Thor Olson Management Graphics Inc. Minneapolis, MNcaracallaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Pigeon Racing PigeonDocument7 pagesPigeon Racing Pigeonsundarhicet83Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dumont's Theory of Caste.Document4 pagesDumont's Theory of Caste.Vikram Viner50% (2)

- A Beginner's Guide To Cry HavocDocument1 pageA Beginner's Guide To Cry HavoccaracallaxPas encore d'évaluation

- ST274 p22 27Document3 pagesST274 p22 27caracallaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Wargame Tactics For Beginners: in The Zone (Of Control)Document2 pagesWargame Tactics For Beginners: in The Zone (Of Control)caracallaxPas encore d'évaluation

- The Battles of Janos HunyadiDocument19 pagesThe Battles of Janos Hunyadicaracallax100% (1)

- The Battles of Janos HunyadiDocument19 pagesThe Battles of Janos Hunyadicaracallax100% (1)

- CPGDocument9 pagesCPGEra ParkPas encore d'évaluation

- Ob AssignmntDocument4 pagesOb AssignmntOwais AliPas encore d'évaluation

- BSBHRM405 Support Recruitment, Selection and Induction of Staff KM2Document17 pagesBSBHRM405 Support Recruitment, Selection and Induction of Staff KM2cplerkPas encore d'évaluation

- Diva Arbitrage Fund PresentationDocument65 pagesDiva Arbitrage Fund Presentationchuff6675Pas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Perdata K 1Document3 pagesJurnal Perdata K 1Edi nur HandokoPas encore d'évaluation

- Imc Case - Group 3Document5 pagesImc Case - Group 3Shubham Jakhmola100% (3)

- Placement TestDocument6 pagesPlacement TestNovia YunitazamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Https Emedicine - Medscape.com Article 1831191-PrintDocument59 pagesHttps Emedicine - Medscape.com Article 1831191-PrintNoviatiPrayangsariPas encore d'évaluation

- Green and White Zero Waste Living Education Video PresentationDocument12 pagesGreen and White Zero Waste Living Education Video PresentationNicole SarilePas encore d'évaluation

- Spitzer 1981Document13 pagesSpitzer 1981Chima2 SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- End of Semester Student SurveyDocument2 pagesEnd of Semester Student SurveyJoaquinPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflecting Our Emotions Through Art: Exaggeration or RealityDocument2 pagesReflecting Our Emotions Through Art: Exaggeration or Realityhz202301297Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ahts Ulysse-Dp2Document2 pagesAhts Ulysse-Dp2IgorPas encore d'évaluation

- 1b SPC PL Metomotyl 10 MG Chew Tab Final CleanDocument16 pages1b SPC PL Metomotyl 10 MG Chew Tab Final CleanPhuong Anh BuiPas encore d'évaluation

- Positive Accounting TheoryDocument47 pagesPositive Accounting TheoryAshraf Uz ZamanPas encore d'évaluation

- Aqualab ClinicDocument12 pagesAqualab ClinichonyarnamiqPas encore d'évaluation

- GooseberriesDocument10 pagesGooseberriesmoobin.jolfaPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Emerging TechnologiesDocument145 pagesIntroduction To Emerging TechnologiesKirubel KefyalewPas encore d'évaluation

- Parts Catalog: TJ053E-AS50Document14 pagesParts Catalog: TJ053E-AS50Andre FilipePas encore d'évaluation

- Commercial Private Equity Announces A Three-Level Loan Program and Customized Financing Options, Helping Clients Close Commercial Real Estate Purchases in A Few DaysDocument4 pagesCommercial Private Equity Announces A Three-Level Loan Program and Customized Financing Options, Helping Clients Close Commercial Real Estate Purchases in A Few DaysPR.comPas encore d'évaluation