Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Assessment and Approach of Patients With Severe Dementia: by Bernard Groulx, MD, FRCPC

Transféré par

sonoiochecomandoDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Assessment and Approach of Patients With Severe Dementia: by Bernard Groulx, MD, FRCPC

Transféré par

sonoiochecomandoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Assessment and Approach of

Patients with Severe Dementia

In the past five years, a number of instruments have been made available for the treatment of

moderate to advanced Alzheimers disease (AD). The second installment of this two-part

article focuses on 12 principles for treating advanced AD.

by Bernard Groulx, MD, FRCPC

he first part of this article,1

expertly written by Dr. Serge

Gauthier, updated us on new instruments and evaluation scales that

allow us to better study the advanced

stages of Alzheimers disease (AD),

as well as the clinical benefits of

cholinergic agents and memantine.

For the second part of this article,

I could have written about the benefits of neurotropics (antidepressants,

neuroleptics, etc.), especially for

behavioral problems commonly

associated with the advanced stages,

but I chose not to. First of all, several articles on the subject have

already been published in past

issues of the Review.2,3 Second, as

the disease progresses, behavioral

problems that do not respondor

respond poorlyto neurotropics

also increase. Such is the case, for

example, observed in disinhibition,

and screaming and wailing.4,5

What can we do when our routine toolsmedicationsgive us

disappointing results? We need to

get back to basics, back to square

one, to a better understanding of the

very nature of this terrible disease.

Retrogenesis

Dr. Groulx is Chief Psychiatrist,

Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue Hospital

and Associate Professor, McGill

University, Montreal, Quebec.

No one understood the nature of AD

better nor described it as well as

Reisberg when he introduced the

concept

of

retrogenesis.6-8

Retrogenesis, already described in

the Review,9,10 demonstrates that

people suffering from AD lose their

cognitive skills and abilities virtually

in the reverse order in which they

learned them. This explains the fact

that, in the early stages of the dis-

10 The Canadian Review of Alzheimers Disease and Other Dementias

ease, patients lose skills acquired

during adolescence (planning,

judgment, social skills, etc.) at the

same time or perhaps even before

their cognitive skills deteriorate.

In the later stages of this disease,

patients regress, feeling and

behaving like two- to five-year-old

children (stage 6) and zero- to

two-year-olds (stage 7), with emotional needs, fears and anxieties.

Stage 6

During this stage, which lasts

approximately two and a half years

and is typically characterized by

behavioral disorders, patients

quickly go from an MMSE score of

10 to a score of zero. When we try

to classify them, we quickly find

evidence to this effect.11 Some of the

dysfunctional behavior is the result

of psychiatric problems that have a

good chance of responding to a pharmacologic approach (Table 1).

Many more behavioral disorders,

however, will not respond or will

respond poorly because they are the

result of retrogenesis. In many cases,

behavioral disorders are reactions to

this regressive or even normal state,

given the context (Table 2). If we

think of an agitated two- or threeyear-old child in an unfamiliar environment with strangers taking care

of them, some of this behavior

(intrusive behavior, disinhibition,

obstinacy, hoarding items, getting

dressed or undressed inappropriately, asking repetitive questions, hiding objects, trying to remove any

restraints, etc.) is certainly not atypical or incomprehensible.

Stage 7

Many patients, I would almost say

happily, do not make it to stage 7.

Many die at the end of stage 6,

often due to pneumonia, a disease

Mark Twain referred to as the

elderlys best friend. Patients

who progress until the final stage of

AD will regress to a mental age of

two to zero years. At the beginning

of this stage, they are able to walk,

but they will eventually lose that

ability. They will only be able to sit

down and will become bedridden,

lying in increasingly fetal positions

due to muscle contraction.

Assessment

In stages 6 and 7, understanding

what the patient is experiencing,

making astute observations and having a good imagination will help

alleviate patients mental pain and

resolve their behavioral problems. Is

there an internal cause for their agitation? Is the patient hungry or

thirsty and unable to express his or

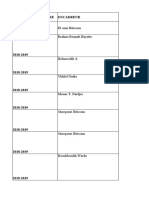

Table 1

Dysfunctional Behaviors in the Elderly with Dementia which

may be Amenable to Pharmacotherapeutic Management

1. Anxiousness: restlessness (hand-wringing, pressured pacing, etc.), fidgeting,

agitation, sometimes self-mutilation

2. Sadness: crying, anorexia, insomnia (particulaly terminal awakening),

nihilism, guilty/paranoid thinking, morbid preoccupation with death

3. Withdrawn: apathy, quiet negativity, anorexia, sullenness, uncooperation,

frequent mutedness, stuporous

4. Markedly bizarre or regressed behavior from previous standards (including

personal appearance and lifetime moral standards)

5. Over-elation: insomnia, psychomotor hyperactivity, rapid/pressured speech,

often disorganized thinking

6. Overly boisterous: verbal hostility, aggressiveness, argumentativeness,

belligerence, physically assaultive

7. Delusions: ideas of influence and reference, jealousy, paranoia, fear,

persecution, grandiosity, and/or tactile (formication)

8. Hallucinations: primarily auditory, visual, and/or tactile (formication)

her needs because he or she has lost

the ability to speak? Is the patient

constipated? Is he or she suffering

from a urinary infection or any other

hidden medical problem? Above all,

is the patient in pain and, again, incapable of expressing himself or herself verbally?

Does the patient respond to an

external cause, meaning the

patients setting or environment? Is

the environment too complex? Does

the patient have too many elements

to cope with? Do the physical, psychological, architectural or other

(environmental) demands exceed

their abilities? Is the environment

overstimulating? Understimulating?

More important, is the environment

hostile? Are the interventions or

interactions from caregivers not

consistent enough, given that

patients see three different groups of

caregivers on the same day?

It is clear that, in the advanced

stages of AD, the most therapeutic

approach is based on understanding retrogenesis: constantly

adjusting to patients (and not the

other way around), understanding

what they are feeling as they are

undergoing this inevitable regression. This approach will result in

interventions that meet the real

needs of patients, delivered in a

professional and, it must be stated,

compassionate manner.

Therapeutic Approach

Allow me to refer to some principles9 that are useful in providing

healthcare interventions to patients

in the advanced stages of AD who

are agitated or in mental pain.

Determine who is agitated.

Ask yourself who is really agitated in a specific situation. Is it the

patient, a member of the family or

The Canadian Review of Alzheimers Disease and Other Dementias 11

Table 2

Dysfunctional Behaviors in the Elderly with Dementia

Usually Not Amenable to Pharmacotherapeutic Management

1. Wandering without aim, pacing

11.Spitting

2. Inappropriate ambulation into

others rooms, toilets, beds

12. Inappropriate undressing/dressing

3. Inappropriate, insulting, hostile or

obnoxious verbalizing (including

perseveration, echolalia,

incoherence, calling out, cursing,

strange noises, yelling or screaming)

13.Constant requests, comments, or

questions

14.Prolonged, frequent repetition of

words/sentences

15. Hiding things

4. Annoying activities (touching, hugging,

unreasonable requests, invading

personal space, banging a walker,

repetitive tapping, rocking, etc.)

16.Pushing a wheelchair-bound

patient

5. Hypersexuality (verbal or physical)

18.Inadvertently putting oneself or

someone else in a hazardous

situation/place

6. Innappropriate sexual activities

(including public masturbation,

exposing oneself)

7. Willfulness or other difficult

personality traits (including refusing

treatments, medications, care or food)

17.Tearing things; flushing items

down the toilet

19.Eating inedible objects (including

feces)

20.Bumping into objects, tripping

over someone or something

8. Hoarding materials (pencils,

straws, cups, toiletries, clothes,

etc. from other patients, nursing

stations, med carts, etc.)

21. Tugging at/removal of restraints

9. Appropriating (stealing) items

from other patients and staff

(glasses, teeth, etc.)

23.Inappropriate isolation (e.g.,

refusal to leave room or socialize)

22.Physical self-abuse (e.g.,

scratching or picking at oneself,

banging head, removing catheter)

10.Inappropriate urination/defecation

(including smearing feces)

24. Physically disruptive (dumping or

throwing food trays, eating from

anothers tray, lying on the floor)

a healthcare provider who is concerned with the patients behavior?

Ensure that the physical environment meets the patients

needs. Organizing the patients

environment should be the first

therapeutic measure taken. The

patients room should be well lit

and adapted to the elderly (calendars, schedules, a clock and familiar objects from the patients

home should also be placed within view). The patient must be able

to have contact with family mem-

bers and have enough room to

move around.

Particular attention should

be paid to the attitude of caregivers. They must reassure

patients, treat them with respect,

help them become aware of their

environment and orient them

every time they interact with

them. The patients functional

capacity must be re-assessed on a

regular basis so caregivers can

modify their interactions accordingly. Personality conflicts

12 The Canadian Review of Alzheimers Disease and Other Dementias

between patients and healthcare

providers must be resolved quickly.

Speak to your patients. It is

easy for us to forget to speak to

patients with advanced AD, especially if they are aphasic and unresponsive. There is nothing better

to reassure AD patients and calm

them than speaking to them in a

natural manner. Telling them what

is going on in the care unit, speaking to them about their past interests or giving them news about

their family creates a normal environment, not to mention that talking to them has therapeutic value

and helps to strengthen the bond

between healthcare professionals

and patients.

Resist the natural temptation to

probe AD patients for information.

It may be difficult for them to answer

simple questions, such as What is

wrong? or Why are you angry?

which will only make them more

confused. Connect with them instead

by saying, for example, I know that

you are angry or You are not feeling well, but I will help youmessages that are much more positive.

Develop efficient communication strategies. In Table 3, you will

find the acronym FOCUSED

which reminds us of the major principles of efficient communication

with patients with advanced AD.12

Avoid construing a patients

agitation, aggressiveness or violence as a personal attack.

Caregivers should never think that

such behavior is directed at them

personally or that their patient is

angry with them.

Never underestimate the benefits of physical activity. Regular

physical activity channels patients

energy, helps them sleep better, and

increases their general well-being.

Never underestimate the benefits of distracting patients during

a crisis. Bring the patient into

another room or suggest another

activity, such as eating, which may

help diffuse aggressive outbursts.

Provide consistent interventions. Regardless of the type of care

plan or strategies that have been

adopted for the patient, make sure

the plan is applied on a regular basis

by the staff of all three work shifts.

The patients family members

are the professional caregivers

best allies. When patients are agitated, the presence of their loved

ones reassures them.

Finally, if the patient is agitated, determine the cause. If the

behavioral problem is a new one,

assess the patients gestures and

try to find out what causes it. If

the disruptive behavior is something the patient has done before,

References:

1. Gauthier S. Treatment of Advanced

Alzheimers Disease (Part I). The Canadian

Alzheimer Disease Review 2005; 8(1):4-6.

2. Van Reekum R. Disinhibitions in

Alzheimers disease: Assessment, prevalence and management. The Canadian

Alzheimer Disease Review 2002; 5(1):4-9.

3. Herrmann N. Pharmacotherapy of

Behavioral Disturbances in Dementia.

The Canadian Alzheimer Disease

Review 1998; 1(2):6-8.

4. Groulx B. Screaming and Wailing in

Dementia patients (Part I). The Canadian

Alzheimer Disease Review 2004; 6(2):11-14.

Table 3

FOCUSED Communication Strategies in Dementia

Face to face:

- face the patient directly

- attract the patients attention

- maintain eye contact

Orientation:

- orient the patient by repeating key words several times

- repeat sentences exactly

- give the patient time to comprehend

Continuity:

- continue the same topic of conversation for as long as possible

- prepare the patient if a new topic must be introduced

Unsticking:

- help the patient become unstuck if he uses a word

incorrectly by suggesting the word hes looking for

- repeat the patients sentence using the correct word

Structure:

- structure your questions to give the patient a simple choice to

respond with

- provide only two options at a time

- provide options the patient would like

Exchange:

- keep up normal exchange of ideas found in conversation

- begin conversations with pleasant, normal topics

- ask easy questions the patient can answer

- give the patient clues as to how to answer

Direct:

- keep sentences short, simple and direct

- use and repeat nouns rather than pronouns

- use hand signals, pictures and facial expressions

find out what caused it in the past

and, more important, find out

what helped resolve the problem.

AD, especially in the advanced

stages, seems to be the most horrible disease. Nonetheless, when we

think of the last 15 years and the

next 25, hope reigns. With two dif-

ferent classes pf medication now

available, there is every reason to

hope for major therapeutic breakthroughs with pharmacologic

research and, perhaps, source cells.

With a better understanding of the

real needs of AD patients, clinicians

and caregivers will be able to provide

a level of healthcare that is increasingly human and compassionate.

5. Groulx B. Screaming and Wailing in

Dementia patients (Part II). The Canadian

Alzheimer Disease Review 2005; 8(1):7-11.

6. Eastwood R, Reisberg B. Mood and behavior, in: Gauthier S (ed): Clinical Diagnosis

and Management of Alzheimer's Disease,

Martin Dunitz, London, 1996, pp. 175-89.

7. Reisberg B, Ferris SH, DeLeon MJ. The

global deterioration scale for assessment

of primary degenerative dementia. Am. J

Psychiatry 1982; 139(9):1136-9.

8. Reisberg B. Functional assessment staging (FAST). Psychopharmacological

Bulletin 1988; 24:653-9.

9. Groulx B. Nonpharmacologic Treatment

of Behavioral Disorders in Dementia.

The Canadian Alzheimer Disease

Review 1998; 2(1):6-8.

10. Tanguay A. The progressive course of

AD: A training tool for caregivers. The

Canadian Alzheimer Disease Review

2002; 5(1):10-2.

11. Maletta GJ. Treatment of behavioral symptomatology of AD, with emphasis on

aggression: Current clinical approaches. Int

Psychogeriatr 1992; 4(Suppl 1):117-30.

12. Ripich DN. Functional communication

with AD patients: A caregiver training

program. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord

1994; 8(3):95-109.

Conclusion

The Canadian Review of Alzheimers Disease and Other Dementias 13

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Mental Status ExamDocument3 pagesThe Mental Status ExamShrests SinhaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Mental Status Exam (MSE)Document5 pagesThe Mental Status Exam (MSE)Huma IshtiaqPas encore d'évaluation

- A Simple Guide to Dementia and Alzheimer's DiseasesD'EverandA Simple Guide to Dementia and Alzheimer's DiseasesÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- PsychopathologyDocument6 pagesPsychopathologybrookegzi88Pas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Case Scenarios PDF 136292509 PDFDocument23 pagesClinical Case Scenarios PDF 136292509 PDFRheeza Elhaq100% (2)

- Global Mental Health Around The World: A Global Look At Depression: An Introductory Series, #9D'EverandGlobal Mental Health Around The World: A Global Look At Depression: An Introductory Series, #9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Azheimer Disease III How is it treated? What is its evolution? How do you prevent it?D'EverandAzheimer Disease III How is it treated? What is its evolution? How do you prevent it?Pas encore d'évaluation

- Behavioral and Psychological Disturbances in Alzheimer Disease: Assessment and TreatmentDocument11 pagesBehavioral and Psychological Disturbances in Alzheimer Disease: Assessment and Treatmenttiara perdana pPas encore d'évaluation

- Tugas Skill - UnlockedDocument9 pagesTugas Skill - Unlockednamasaya1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Autism Spectrum Disorder: A guide with 10 key points to design the most suitable strategy for your childD'EverandAutism Spectrum Disorder: A guide with 10 key points to design the most suitable strategy for your childPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of The Older Adults (Geriatrics)Document14 pagesAssessment of The Older Adults (Geriatrics)Yna Joy B. LigatPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: by Oliver Sacks | Includes AnalysisD'EverandSummary of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: by Oliver Sacks | Includes AnalysisPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Capstone PaperDocument15 pagesFinal Capstone Paperapi-478784238Pas encore d'évaluation

- Psych p3Document8 pagesPsych p3Fatima MajidPas encore d'évaluation

- Alzheimer's Disease Student's Name Student's ID Course NameDocument7 pagesAlzheimer's Disease Student's Name Student's ID Course NameandrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Research ProposalDocument17 pagesResearch Proposalmullamuskaan95Pas encore d'évaluation

- Complex Cases and Comorbidity in Eating Disorders: Assessment and ManagementD'EverandComplex Cases and Comorbidity in Eating Disorders: Assessment and ManagementPas encore d'évaluation

- CBT Manual OcdDocument19 pagesCBT Manual OcdRedefining Self with MeghaPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding The Individual With Alzheimer's Disease: Can Socioemotional Selectivity Theory Guide Us?Document10 pagesUnderstanding The Individual With Alzheimer's Disease: Can Socioemotional Selectivity Theory Guide Us?Andre ZulkhasogiPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Health Case StudyDocument15 pagesMental Health Case Studyapi-508142358Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dealing with Depression: A commonsense guide to mood disordersD'EverandDealing with Depression: A commonsense guide to mood disordersÉvaluation : 2 sur 5 étoiles2/5 (1)

- CognitiveDocument19 pagesCognitiveLaila MajenumPas encore d'évaluation

- The Dysregulated Adult: Integrated Treatment ApproachesD'EverandThe Dysregulated Adult: Integrated Treatment ApproachesPas encore d'évaluation

- Older People - Patterns of Illness, Physiological Changes and Multiple PathologyDocument4 pagesOlder People - Patterns of Illness, Physiological Changes and Multiple PathologyTweenie DalumpinesPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 6 Revised Final Research With AppendicesDocument71 pagesGroup 6 Revised Final Research With AppendicesAbby GutierrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Hysteria: Personal PracticeDocument2 pagesHysteria: Personal PracticeNando AswinPas encore d'évaluation

- Weathering the Storm: A Guide to Understanding and Overcoming Mood DisordersD'EverandWeathering the Storm: A Guide to Understanding and Overcoming Mood DisordersPas encore d'évaluation

- Abnormal Psychology IntroductionDocument11 pagesAbnormal Psychology IntroductionAyesha FayyazPas encore d'évaluation

- Ocd-Treatment Publishing NardoneDocument62 pagesOcd-Treatment Publishing Nardoneneri100% (2)

- When Traditional CareDocument23 pagesWhen Traditional CareEvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Alzheimer's Disease: The Complete IntroductionD'EverandAlzheimer's Disease: The Complete IntroductionÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (3)

- Study Notes PsychiatryDocument50 pagesStudy Notes PsychiatryMedShare90% (10)

- Mood DisordersDocument14 pagesMood DisordersHayat AL AKOUMPas encore d'évaluation

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Clinical Picture and Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment ImplicationsDocument45 pagesObsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Clinical Picture and Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Implicationstennisnavis4Pas encore d'évaluation

- Alzheimer's Disease MemorDocument11 pagesAlzheimer's Disease MemorPatrick OrtizPas encore d'évaluation

- Overcoming Bipolar Disorder - 17 Ways To Manage Depression And Multiple Moods Without Going CrazyD'EverandOvercoming Bipolar Disorder - 17 Ways To Manage Depression And Multiple Moods Without Going CrazyPas encore d'évaluation

- Examen Final de Idioma II InglesDocument5 pagesExamen Final de Idioma II InglesLa Spera OttavaPas encore d'évaluation

- Body Dysmorphic DisorderDocument6 pagesBody Dysmorphic DisorderAllan DiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Final PaperDocument7 pagesFinal Paperapi-339682129Pas encore d'évaluation

- Davys Ongwae Assignment 2Document5 pagesDavys Ongwae Assignment 2Isaac MwangiPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesLiterature ReviewResianaPutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Depression and The Elderly - FinalDocument8 pagesDepression and The Elderly - Finalapi-577539297Pas encore d'évaluation

- Psychopathology PDFDocument26 pagesPsychopathology PDFBenedicte NtumbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Abnormal PsychologyDocument70 pagesAbnormal PsychologyHec ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- Chap12 Abnormal PsychDocument34 pagesChap12 Abnormal PsychshaigestPas encore d'évaluation

- FRAILTY - Someone Who Is Skinny, Weak and Vulnerable (Cannot Be Diagnosed Based On Appearance)Document14 pagesFRAILTY - Someone Who Is Skinny, Weak and Vulnerable (Cannot Be Diagnosed Based On Appearance)Jhon Mark Miranda Santos100% (1)

- Analyse The Biological and Diathesis-Stress Paradigms To Psychopathology and Comment About Their Strengths and Weaknesses.Document5 pagesAnalyse The Biological and Diathesis-Stress Paradigms To Psychopathology and Comment About Their Strengths and Weaknesses.Paridhi JalanPas encore d'évaluation

- 20 Questions Psychiatric Emergencies PDFDocument4 pages20 Questions Psychiatric Emergencies PDFakelog getahunPas encore d'évaluation

- Patoloji Notlarım: Abnormal Psychology Family AggregationDocument5 pagesPatoloji Notlarım: Abnormal Psychology Family AggregationMelike ÖnolPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental RetardationDocument10 pagesMental RetardationYAMINIPRIYANPas encore d'évaluation

- The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: by Oliver Sacks | Key Takeaways, Analysis & Review: And Other Clinical TalesD'EverandThe Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: by Oliver Sacks | Key Takeaways, Analysis & Review: And Other Clinical TalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument15 pagesReview of Related Literaturemarielle rumusudPas encore d'évaluation

- 16 Schragand Edwards Psychogenic Movement Disorders 2012Document10 pages16 Schragand Edwards Psychogenic Movement Disorders 2012آسيل محمدPas encore d'évaluation

- UnconsciousnessDocument6 pagesUnconsciousnessSeema RahulPas encore d'évaluation

- Calmer: Medical Events with Cognitively Impaired ChildrenD'EverandCalmer: Medical Events with Cognitively Impaired ChildrenPas encore d'évaluation

- Autism Revealed: All you Need to Know about Autism, Autistic Children and Adults, How to Manage Autism, and More!D'EverandAutism Revealed: All you Need to Know about Autism, Autistic Children and Adults, How to Manage Autism, and More!Pas encore d'évaluation

- Harciareketal 2011Document17 pagesHarciareketal 2011sonoiochecomandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychological Correlates of Sleep ApneaDocument14 pagesPsychological Correlates of Sleep ApneasonoiochecomandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Applying Skinner's Analysis of Verbal Behavior To Persons With DementiaDocument21 pagesApplying Skinner's Analysis of Verbal Behavior To Persons With DementiasonoiochecomandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Alzheimer in Down SyndromeDocument12 pagesAlzheimer in Down SyndromesonoiochecomandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Two Dimensions of Anosognosia in Patients With Alzheimer's Disease. Reliability and Validity of The Japanese Version of The Anosognosia Questionnaire For Dementia (AQ-D)Document7 pagesTwo Dimensions of Anosognosia in Patients With Alzheimer's Disease. Reliability and Validity of The Japanese Version of The Anosognosia Questionnaire For Dementia (AQ-D)sonoiochecomandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sumerians Elamites Egyptians: AmoritesDocument5 pagesSumerians Elamites Egyptians: AmoritessonoiochecomandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Abdominsl Surgery MergedDocument141 pagesAbdominsl Surgery MergedTemitope AdeosunPas encore d'évaluation

- Paeds EMQDocument8 pagesPaeds EMQfasdPas encore d'évaluation

- Donanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease: Original ArticleDocument14 pagesDonanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease: Original ArticleBalla ElkhiderPas encore d'évaluation

- Computed Tomography & Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Neurological Disorder Diagnostic TestsDocument20 pagesComputed Tomography & Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Neurological Disorder Diagnostic TestsissaiahnicollePas encore d'évaluation

- Pneumonia in ChildrenDocument22 pagesPneumonia in ChildrenHarsha HinklesPas encore d'évaluation

- PESCI Recalls PDFDocument9 pagesPESCI Recalls PDFDanishPas encore d'évaluation

- PTSD and Autoimmune DiseasesDocument24 pagesPTSD and Autoimmune DiseasesEnida XhaferiPas encore d'évaluation

- Occt651 - Occupational Profile Paper - FinalDocument20 pagesOcct651 - Occupational Profile Paper - Finalapi-293182319Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Head and Neck Lectures: Anas Ibrahim YahayaDocument242 pagesThe Head and Neck Lectures: Anas Ibrahim YahayaBilkisu badamasiPas encore d'évaluation

- UNIVERSITY of SAN AGUSTIN - Capillary Electrophoresis Lecture 2023Document231 pagesUNIVERSITY of SAN AGUSTIN - Capillary Electrophoresis Lecture 2023alyssa apudPas encore d'évaluation

- Activity # 7 Fluid and Electrolyte Balance (WITH NCP)Document15 pagesActivity # 7 Fluid and Electrolyte Balance (WITH NCP)Louise OpinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vitreomacular Traction: I Wayan Ardy Paribrajaka Vitreoretina Division of Bali Mandara Eye HospitalDocument29 pagesVitreomacular Traction: I Wayan Ardy Paribrajaka Vitreoretina Division of Bali Mandara Eye HospitalArdyPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 001Document6 pagesCH 001Maaz KhajaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Case of Alport Syndrome Presented With Bilateral Anterior LenticonusDocument3 pagesA Case of Alport Syndrome Presented With Bilateral Anterior LenticonusBOHR International Journal of Current Research in Optometry and Ophthalmology (BIJCROO)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Icmr Specimen Referral Form For Covid-19 (Sars-Cov2) : (If Yes, Attach Prescription If No, Test Cannot Be Conducted)Document2 pagesIcmr Specimen Referral Form For Covid-19 (Sars-Cov2) : (If Yes, Attach Prescription If No, Test Cannot Be Conducted)ShakirShafiPas encore d'évaluation

- Complications of DialysisDocument7 pagesComplications of DialysisDilessandro PieroPas encore d'évaluation

- Major Intra and Extracellular ElectrolytesDocument9 pagesMajor Intra and Extracellular ElectrolytesJana BluePas encore d'évaluation

- Biological Factors Responsible For Failure of Osseointegration in OralimplantsDocument7 pagesBiological Factors Responsible For Failure of Osseointegration in OralimplantsKarim MohamedPas encore d'évaluation

- Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral NeurologyDocument302 pagesNeuropsychiatry and Behavioral NeurologyTomas Holguin70% (10)

- Mehlmanmedical Hy Neuro Part IDocument18 pagesMehlmanmedical Hy Neuro Part IAzlan OmarPas encore d'évaluation

- Cutaneous Reactions To Chemo and RadiotherapyDocument37 pagesCutaneous Reactions To Chemo and Radiotherapyimdad khanPas encore d'évaluation

- RBCs Abnormal Morphology FinalDocument33 pagesRBCs Abnormal Morphology FinalInahkoni Alpheus Sky OiragasPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Write Killer AdsDocument15 pagesHow To Write Killer Adshfi11939100% (9)

- Gambar Rajah Menunjukkan Satu Neuron.: The Diagram Shows A NeuronDocument3 pagesGambar Rajah Menunjukkan Satu Neuron.: The Diagram Shows A Neuronkikio123Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1 thePoisonedNeedle PDFDocument432 pages1 thePoisonedNeedle PDFcas100% (4)

- Fats and OilsDocument36 pagesFats and Oilstafer692002100% (1)

- Biomechanical Basis of Foot Orthotic PrescriptionDocument6 pagesBiomechanical Basis of Foot Orthotic PrescriptionDusan OrescaninPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogue Master 2019-2021Document309 pagesCatalogue Master 2019-2021ChaoukiMatimaticPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 - Neurodiagnostics II - Essentials of Neuroradiology LectureDocument44 pages6 - Neurodiagnostics II - Essentials of Neuroradiology LectureShailendra Pratap SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Uploaded Activity 3 - Alyssa Angelaccio 1Document3 pagesUploaded Activity 3 - Alyssa Angelaccio 1api-544674720Pas encore d'évaluation