Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

SSRN Id1274605

Transféré par

galatimeTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

SSRN Id1274605

Transféré par

galatimeDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A LIGHTWEIGHT NOTE ON SUCCESS IN MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS

June 2004

Dr Staffan Canback, Canback Dangel LLC

Merger and acquisition activity is picking up.

The first quarter saw the highest level of global

M&A activity since 2000.1 It may therefore be

interesting to review what we have learnt about

the science of M&A lately. Perhaps surprisingly,

there is growing evidence that making acquisitions is one of the best and safest ways to sustain

shareholder value.

Yet should we not have learnt that M&A usually

does not make sense? That most acquisitions

destroy value? That deal making is prompted by

CEO vanity and not by economic reality? Not

necessarily. Contrary to popular opinion, the

vast majority of M&A deals succeed and add

value to shareholders and society.2

Conventional wisdom holds that much less than

half of all mergers succeed.3 The facts tell a different story. This story is well known in academic circles, but is at best only anecdotally known

among business executives. This review summarizes the most important research findings and

explains why executives pursue acquisitions. It

is not because of folly, but rather because it is in

the interest of their shareholders.

The first lesson learnt is that mergers and acquisitions pay off. That is, the shareholders of the

new entity earn their required return or more.

Nine studies conducted since 1990 (averaging

190 deals each) report an average return of 5%

above the shareholders opportunity cost.4

The mistake we frequently make is to expect

extraordinarily high returns. 2030% of deals

show such returns.5 Maybe this explains the

common belief that few deals succeed. But as

Professor Bruner at the Darden Graduate School

of Business points out: One should conclude

that M&A does payThe reality is that 6070%

of all M&A transactions are associated with financial performance that at least compensates

investors for their opportunity cost.6

Within this context, it is not surprising that the

shareholders of target companies have high re-

turns. Acquisition premiums are around 20

40%,7 which is the reward to shareholders for

giving up control of their company. The average

return reported in 13 studies since 1990 (averaging 324 deals each) was 26%.8

Shareholders of the acquiring company break

even. That is, they earn their cost of capital. 22

studies conducted since 1990 (averaging 505

deals each) report an average return of 0.5%.9

Bear in mind though that the bidder usually is

larger than the target, so the 0.5% return underreports the actual return (around 23%).10 Interestingly, other classes of investments such as

R&D, marketing, and capital expenditures have

similar returns above the cost of capital: around

1%.11

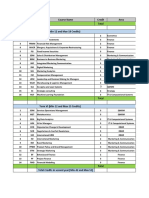

The table below averages the results from

various studies. We should recognize that

numbers disguise significant variability. For

ample, deals during the 19982001 bubble

less well.

Combined

Target

Bidder

the

the

exdid

AVERAGE M&A RETURNS

Return above

Probability of

opportunity cost positive return

5%

68%

26%

86%

0.5%

51%

The second lesson learnt is that certain types of

deals are more successful than others. An important finding is that value companies are more

successful than glamour companies in M&A.

A value company is a company with a moderate

or low market-to-book ratio; a glamour company

is a company with a high relative valuation

where executives are lauded by the business

press and analysts. Typically, value acquirers

show returns of +3% while glamour acquirers

show returns of 6%.12

Related to the value and glamour distinction,

cash tender offers outperform deals where the

acquirer pays with stock. On average, this effect

leads to a 4% difference in return.13 In fact,

Staffan Canback is Managing Director of Canback Dangel (http://canback.com)

Inquiries: scanback@canback.com or +1-617-399-1300

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1274605

when a glamour company makes an all-stock

acquisition, the market views this as a signal that

the acquirer is overvalued. Thus, a glamour

stock-deal has a high probability of failing and

the glamour acquirer on average loses 17% of its

value over a three-year period.14

Further, related acquisitions are more successful

than diversifying deals. The days of conglomerates and diversification as a strategy are long

gone, and focusing on the core business is the

hallmark of most companies. This is understandable because unrelated acquisitions show negative returns of 14% on average.15 We also know

that geographic expansion is less attractive than

product expansion, reducing the shareholder return by 23%.16

Finally, small acquirers do better than large acquirers. While the shareholders of large acquirers show slightly negative returns, small acquirers show positive returns of 23%.17 This is in

part because small acquirers tend to buy private

companies or divisions of public companies,

while large acquirers often buy public companies;18 in part because large acquirers tend to

overestimate synergies.19

The third lesson is that preparation and discipline matter. Pre-deal, it is critical to pinpoint the

strategic logic of the deal and the synergies that

will be extracted. The market tends to favor hard

synergies such as cost cutting more than soft

synergies such as cross-selling opportunities.20

This is rational because, on average, close to

90% of declared cost synergies are realized, but

only 60% of declared revenue synergies.21

During deal execution, maintaining bid discipline is critical. Many failed acquisitions are the

results of unrealistically high bids. However,

this does not imply that bids should be accretive.

The accretion/dilution distinction is a false issue

and it has little or no impact on the markets

reaction, while price-versus-value fundamentals

do.22 Further, the use of bulge-bracket investment banks tends to increase the likelihood of

closing a deal, but reduces the return to shareholders.23

Post-deal, two success factors stand out.24 First,

successful acquirers tend to integrate the targets

operations quickly. An acquirer that lets the target maintain independence is less likely to be

successful. Second, it is critical to retain the targets executives. Too often, the executives flee

the new company as soon as their incentive programs allow it. If this happens, we can predict

that the acquisition will not pay off.

In sum, M&A often pays off and we have made

major strides in turning successful deal making

from an art to a science. Indeed, a KPMG survey

shows that more than 80% of executives are satisfied with their M&A activities.25 This does not

mean that M&A is easy and, as always, the details in the pudding. But we do see the contours

of what makes a deal succeed. It is now possible

to calculate the value-creation starting point for

any prospective deal based on the deals characteristics. This is in sharp contrast to knowledge

only a decade ago.

1

Thomson Financial, p. 1

Lu, p. 32

3

e.g., Grubb and Lamb, pp. 9-14

4

Bruner, p. 21

5

Andrade et al., p. 27; Bruner, p. 5

6

Bruner, p. 14

7

Andrade et al., p. 27; Christofferson et al., p. 1

8

Bruner, p. 17

9

Bruner, pp. 18-20

10

Moeller et al., p. 30; Bruner, p. 6

11

Andrade et al., p. 20

12

Lu, p. 11; Rau and Vermaelen, p. 1

13

Andrade et al., p. 11

14

Rau and Vermaelen, p. 1

15

Bruner, p. 9

16

Canback, pp. 169-176

17

Moeller et al., p. 29

18

Moeller et al., pp. 30, 32

19

Moeller et al., pp. 4, 23-24

20

Bruner, p. 9

21

Christofferson et al., pp. 2-3

22

Andrade, pp. 5-6

23

Rau and Rodgers, p. 5

24

Zollo and Leshchinskii, pp. 23, 31

25

Kelly et al., p. 2

2

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1274605

REFERENCES

Andrade, G. 1999. Do Appearances Matter? The Impact of EPS Accretion and Dilution on Stock Prices. Boston:

Harvard Business School.

Andrade, G., M Mitchell and M Stafford. 2000. New Evidence and Perspectives on Mergers. Boston: Harvard Business School.

Bruner, F. 2001. Does M&A Pay? A Survey of Evidence for the Decision-Maker. Charlotteville: Darden Graduate

School of Business.

Canback, S. 2002. Bureaucratic Limits of Firm Size: Empirical Analysis Using Transaction Cost Economics. Uxbridge: Brunel University.

Christofferson, SA, RS McNish and DL Sias. 2004. Where Mergers Go Wrong. McKinsey Quarterly, 40 (Winter):

1-6.

Grubb, TM and RB Lamb. 2000. Capitalize on Merger Chaos. New York: Free Press

J. Kelly, C. Cook, and D. Spitzer. 1999. Unlocking Shareholder Value: The Key to Success. London: KPMG.

Lu, Q. 2001. Do Mergers Destroy Value? Evidence from Failed Bids. Chicago: Kellogg Schoolof Management.

Moeller, SB, FP Schlingemann and RM Stulz. 2003. Firm Size and the Gains from Acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, Forthcoming.

Rau, PR and KJ Rodgers. 2002. Do Bidders Hire Top-Tier Investment Banks to Certify Value? West Lafayette:

Krannert Graduate School of Management.

Rau, PR and T Vermaelen. 1998. Glamour, Value and the Post-Acquisition Performance of Acquiring Firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 49 (2): 223-253.

Thomson Financial. 2004. Mergers Unleashed. March 31, 2004 [cited May 22, 2004]. Available from

<http://www.thomson.com/financial/investbank/fi_investbank_league_table.jsp#mergers_acquisitions>.

Zollo, M and D Leshchinskii. 2000. Can Firms Learn to Acquire? Do Markets Notice? Wharton

Business School.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- SSRN Id4335210Document50 pagesSSRN Id4335210galatimePas encore d'évaluation

- 50 Journals Used in FT Research Rank - Financial TimesDocument3 pages50 Journals Used in FT Research Rank - Financial TimesgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- SMJ Author Instructions January 2022Document17 pagesSMJ Author Instructions January 2022galatimePas encore d'évaluation

- My 10 Rules For Public Speaking - by Ted GioiaDocument15 pagesMy 10 Rules For Public Speaking - by Ted GioiagalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- An Mturk Crisis? Shifts in Data Quality and The Impact On Study ResultsDocument10 pagesAn Mturk Crisis? Shifts in Data Quality and The Impact On Study ResultsgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- FT50 Journals Used in FT Research Rank - Financial TimesDocument3 pagesFT50 Journals Used in FT Research Rank - Financial TimesgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- Kurt Vonnegut - Troubling - Info PDFDocument1 pageKurt Vonnegut - Troubling - Info PDFgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S2212144719301206 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S2212144719301206 Main PDFgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- Pandit 1957 ENT in IndiaDocument4 pagesPandit 1957 ENT in IndiagalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- Scopus CiteScore 2021 PDFDocument3 pagesScopus CiteScore 2021 PDFgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- My Teacher - Charlie MungerDocument6 pagesMy Teacher - Charlie MungergalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- Chanmyay Practical Insight PDFDocument64 pagesChanmyay Practical Insight PDFgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate Venture CapitalDocument32 pagesCorporate Venture CapitalgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- Venture CapitalDocument10 pagesVenture CapitalgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Talent PDFDocument8 pagesThe Little Book of Talent PDFgalatime93% (14)

- Constellation SoftwareDocument11 pagesConstellation SoftwaregalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- Business ModelDocument1 pageBusiness ModelgalatimePas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Small & Medium-Sized Entities (Smes)Document8 pagesSmall & Medium-Sized Entities (Smes)Levi Emmanuel Veloso BravoPas encore d'évaluation

- Brief Note On The Trusteeship Approach As Proposed by Mahatma Gandhi - Business Studies - Knowledge HubDocument2 pagesBrief Note On The Trusteeship Approach As Proposed by Mahatma Gandhi - Business Studies - Knowledge HubSagar GavitPas encore d'évaluation

- Uber & The Ethics of SharingDocument11 pagesUber & The Ethics of SharingEileen OngPas encore d'évaluation

- SDLC ResearchgateDocument10 pagesSDLC ResearchgateAlex PitrodaPas encore d'évaluation

- Stock Update - HCL Tech - HSL - 061221Document12 pagesStock Update - HCL Tech - HSL - 061221GaganPas encore d'évaluation

- Infosys - Competitor AnalysisDocument2 pagesInfosys - Competitor AnalysisAkhilM100% (1)

- Techm Work at Home Contact Center SolutionDocument11 pagesTechm Work at Home Contact Center SolutionRashi ChoudharyPas encore d'évaluation

- Activiity 2 Investment in AssociateDocument3 pagesActiviity 2 Investment in AssociateAldrin Cabangbang67% (3)

- Price Action TradingDocument1 pagePrice Action TradingMustaquim YusopPas encore d'évaluation

- Annual Return of A Company (Other Than A Company Limited by Guarantee)Document5 pagesAnnual Return of A Company (Other Than A Company Limited by Guarantee)ramiduyasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Functional RequirementDocument6 pagesFunctional RequirementmanishPas encore d'évaluation

- Parkin Laboratories Sales Target Dilemma: Submitted To-Dr.. Sandeep Puri Submitted byDocument13 pagesParkin Laboratories Sales Target Dilemma: Submitted To-Dr.. Sandeep Puri Submitted byRomharshit KulshresthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Word DiorDocument3 pagesWord Diorlethiphuong15031999100% (1)

- Understanding Process Change Management in Electronic Health Record ImplementationsDocument35 pagesUnderstanding Process Change Management in Electronic Health Record ImplementationsssimukPas encore d'évaluation

- Configuration Management Process GuideDocument34 pagesConfiguration Management Process GuideRajan100% (4)

- Main BodyDocument7 pagesMain Bodykamal lamaPas encore d'évaluation

- EY - Robotic Process Automation (RPA) in InsuranceDocument25 pagesEY - Robotic Process Automation (RPA) in InsuranceEric LinderhofPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Zayredin AssignmentDocument26 pagesFinal Zayredin AssignmentAmanuelPas encore d'évaluation

- Graphic Design Intern (WFH) : FampayDocument4 pagesGraphic Design Intern (WFH) : FampayS1626Pas encore d'évaluation

- New Heritage Doll - SolutionDocument4 pagesNew Heritage Doll - Solutionrath347775% (4)

- Virtusa Pegasystems Engagement Success StoriesDocument20 pagesVirtusa Pegasystems Engagement Success StoriesEnugukonda UshasreePas encore d'évaluation

- BA TecniquesDocument55 pagesBA Tecniquesloveykhurana5980100% (2)

- Project of Merger Acquisition SANJAYDocument65 pagesProject of Merger Acquisition SANJAYmangundesanju77% (74)

- Electives Term 5&6Document28 pagesElectives Term 5&6GaneshRathodPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Hub: National Case Study Challenge 2021Document13 pagesBusiness Hub: National Case Study Challenge 2021HimansuRathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Eaas Executive SummaryDocument15 pagesEaas Executive SummarystarchitectPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 07Document72 pagesCH 07Ivhy Cruz Estrella100% (1)

- Assistant Manager - CSR (Mumbai)Document2 pagesAssistant Manager - CSR (Mumbai)Kumar GauravPas encore d'évaluation

- Electronic Business SystemsDocument44 pagesElectronic Business Systemsmotz100% (4)

- Details FM DATADocument212 pagesDetails FM DATAAbhishek MishraPas encore d'évaluation