Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Intro To Linguistics PDF

Transféré par

Anonymous abwXcGDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Intro To Linguistics PDF

Transféré par

Anonymous abwXcGDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Introduction to Linguistics / 1

Introduction to linguistics

Textbook

The textbook is Barry J. Blake, All about Language (Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 2008; ISBN 978-0-19-923840-8), which you must buy. (You can buy it wherever

you wish; within amazon.co.jp its at http://snipurl.com/amj-blake . Of course you are

welcome to buy a used copy, but beware of scribbling by the previous owner, delays,

or expensive postage.)

Because Blakes book is new, I dont think it has yet been reprinted. It has some

faults. Ill point out those that I notice. If you look hard you might notice one or two

more; if so, please tell me. (If your copy has been corrected, please tell me that too.)

Supplementary texts: why and where

If theres something you cant understand in the book (or in what I say or write),

read it again slowly or ask me, and also check that youve understood what preceded

it. If youre still in trouble, try looking in an additional book sometimes a different

perspective makes everything clear.

Im going to name a lot of books. You wont have to look in any of them, but its

more helpful to let you choose than to specify just one or two books that might have

already been borrowed by somebody else.

For each of the books below, you see the location:

[CR] , [RR] in the GIS Common Room; in the GIS Reference Room: note that a

book can move between the two

[L1]

on the 1st floor of Ichigaya library

[LB1], [LB2], [LB3], [LB4] on the 1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th basement of Ichigaya

library

[TL]

in Tama library (can easily be ordered from/for Ichigaya)

Whats between { and } is the call number: the number on the label on the

spine that says where the book should be. And <*> means that its in the series

Oxford Introductions to Language Study; these books are particularly compact and

are written for beginners.

General books on language and linguistics

Bergmann, Anouschka, et al., eds. Language Files: Material for an Introduction to

Language and Linguistics. 10th ed. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2007.

[RR] {801/BE}

Cruz-Ferreira, Madalena, and Sunita Anne Abraham. The Language of Language: Core

Concepts in Linguistic Analysis. 2nd ed. Singapore: Longman Pearson, 2005. [LB4]

{801/1256}

Fasold, Ralph W., and Jeff Connor-Linton, eds. An Introduction to Language and Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [L1] {801/FA}

Fromkin, Victoria, et al. An Introduction to Language. 8th ed. Boston: Thomson, 2006.

[LB4] {801/814/8}

Hall, Christopher. An Introduction to Language and Linguistics: Breaking the Language

Spell. London: Continuum, 2005. [LB4] {801/1138}

Hudson, Grover. Essential Introductory Linguistics. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2000.

[LB4] {801/781}

OGrady, William, et al. Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction. 5th ed. New York:

Introduction to Linguistics / 2

Bedford/St Martins, 2005. [RR] {801/OG}

Radford, Andrew, et al., Linguistics: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2009. [RR] {801/RA}

Widdowson, H. G. Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. <*>

[CR] {801/WI}

Yule, George. The Study of Language. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

2006. [L1] {801/YU}

Reference books about language

Bauer, Laurie. The Linguistics Students Handbook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University

Press, 2007. [CR] {801/BA}

Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Abingdon,

Oxon: Routledge, 2006. [RR] {803.3/BU}

Crystal, David. A Dictionary of Language. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

2001. [CR] {803.3/CR}

Crystal, David. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 5th ed. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2003. [RR] {803/CR} This will probably be too difficult for you.

Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. 2nd ed., ed. Keith Brown. 14 vols. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006. [LB1] {R803/28}

Encyclopedia of Linguistics, ed. Philipp Strazny. 2 vols. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn,

2005. [LB1] {R803/29}

Finch, Geoffrey. Key Concepts in Language and Linguistics. Basingstoke, Hants:

Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. [CR] {801/FI}

International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed., ed. William J. Frawley. 4 vols.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. [LB1] {R803/9/2}

Trask, R. L. Key Concepts in Language and Linguistics. London: Routledge, 1999.

[CR] {803.3/TR}

General-interest books about language

Bauer, Laurie, and Peter Trudgill, eds. Language Myths. London: Penguin, 1998.

[CR] {801/BA}

Bauer, Laurie, et al. Language Matters. Basingstoke, Hants: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

[RR] {801/BA}

Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. [RR] {830.36/CR}

Jackendoff, Ray. Patterns in the Mind. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1993.

[LB4] {801/320} / New York: Basic, 1994. [L1] {801/JA}

Napoli, Donna Jo. Language Matters: A Guide to Everyday Questions about Language.

New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. [CR] {801/NA}

Pinker, Steven. The Language Instinct The New Science of Language and Mind.

London: Penguin, 1995. [CR] {801.01/PI}

Rickerson, E. M., and Barry Hilton, eds. The Five-Minute Linguist. London: Equinox,

2006. [CR] {804/RI}

Introduction to Linguistics / 3

Barry J. Blake, All about Language

Introduction

p. 3

all languages have a vowel sound like the one in words like cut. . . . For the

kind of English that I happen to speak, this particular sound is either [] (openmid back unrounded) or [] (near-open central), probably the former. Only a

minority of languages have exactly [], though all languages have one much

like it.

2. Word Classes

Blake has a rather traditional idea of which English words are which parts of

speech. This doesnt agree with much recent theoretical work or even recent descriptive work, such as Huddleston and Pullums The Cambridge Grammar of the English

Language, a book that he recommends (pp. 100, 310) and that Ill call CGEL.

pp. 1112

Nouns can modify nouns: e.g. the brick in brick wall. Some writers distinguish between verbs, which have clear meaning (cut, throw, complete, live,

hear, etc), and auxiliaries, which do not (be, do, may, shall); others (such as

Blake himself later in the book) call the former lexical verbs (or thematic verbs)

and the latter auxiliary verbs (or auxiliaries).

pp. 1213

CGEL calls these determinatives rather than determiners.

p. 14 Some writers put who, anybody, etc among quantifiers (a group that includes

any, all, every, etc) rather than pronouns, put my, etc among pronouns, and/or

put all pronouns among determiners.

p. 15 CGEL puts what Blake calls subordinating conjunctions among adverbs.

pp. 1718

CGEL classes Blakes verbal particles (e.g. out in took the rubbish out)

as intransitive prepositions: just as cough is a verb without an object, so out is a

preposition without an object.

Below and for the later chapters, Reference means books that you might use for

additional reference purposes (in addition to the books listed above); Sources and

further reading tells you where Blakes recommended books and other materials can

be found (if Ive located them anywhere at Hosei or on the web), and adds materials I

have mentioned and a very few of my own recommendations.

Reference

Biber, Douglas, et al, eds. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow,

Essex: Longman, 1999. [RR] {835/BI} [LB4] {R835/135}

Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey K. Pullum, eds. The Cambridge Grammar of the

English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [RR] {835/HU}

[LB4] {835/154}

Introduction to Linguistics / 4

Sources and further reading

Bloor, Thomas, and Meriel Bloor. The Functional Analysis of English: A Hallidayan

Approach. 2nd ed. London: Arnold, 2004. [LB4] {835/167}

Radford, Andrew. English Syntax: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2004. [RR] {835.1/RA} / [LB4] {835/162} Chapter 2.

3. Forming New Words

p. 29 Various dictionaries say that metrosexual and retrosexual come from metroand heterosexual. Actually neologisms (new words) tend to trigger more neologisms (so the new word maser, a term thats now of only historic interest, led

to laser), and retrosexual is likely to have come primarily from metrosexual.

p. 33 Nigger is definitely not the Latin word for black, although it is derived from

the Latin word for black.

Reference

Bauer, Laurie. A Glossary of Morphology. Washington, DC: Georgetown University

Press, 2004. [RR] {801.5/BA}

Sources and further reading

Adams, Valerie. Complex Words in English. Harlow, Essex: Longman, 2001. [RR] {835/

AD}

Adams, Valerie. An Introduction to Modern English Word Formation. London: Longman,

1975. [LB3] {E3/549/7}

Aronoff, Mark, and Kirsten Fudeman. What is Morphology? Malden, Mass.: Blackwell,

2005. [RR] {801.5/AR} / [LB4] {801/1110}

Bauer, Laurie. English Word-Formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

[LB3] {E3/576}

Bauer, Laurie. Introducing Linguistic Morphology. 2nd ed. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2003. [RR] {801.5/BA}

Carstairs-McCarthy, Andrew. An Introduction to English Morphology: Words and Their

Structure. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003. [RR] {831.5/CA}

Coates, Richard. Word Structure. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 1999. [CR] {801.5/CO}

Katamba, Francis. English Words: Structure, History, Usage. 2nd ed. Abingdon, Oxon:

Routledge, 2005. [RR] {832/KA}

4. Meaning of Words

p. 46 Huddleston and Pullum reject the notion of phrasal verbs, and instead regard

them as verbs with particles (most of which are intransitive prepositions). See A

Students Introduction to English Grammar, pp. 14446.

p. 47 The word crayfish came from an Old French word escrevisse, and the -visse part

of that sounded similar to the way that fish was pronounced at the time.

Introduction to Linguistics / 5

Dictionaries

Here are some of the dictionaries that Blake briefly describes. (In order to save space,

Ill skip most of the publication details) The library is particularly well stocked with

EnglishEnglish (and EnglishJapanese) dictionaries, and a little investigation will show

you which other ones are notable and where they are in the library.

Cawdrey, Robert. A Table Alphabeticall. 1604. Reprinted 1970. [TL] {A3/182/226}

Johnson, Samuel. A Dictionary of the English Language. 2 vols. 1755. Reprinted 1882.

[LB3] {E2a/21} / Reprinted 1968. [LB3] {E2a/243} / Reprinted 1983 (in one

volume). [LB1] {R833/80} / Reprinted 1985. [LB4] {R 833/38}

Oxford English Dictionary. 12 vols (plus supplements). 1933. [LB3] {E2a/5} / [LB3]

{E2a/58}

Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 20 vols. 1989. [LB1] {R833/25}

Webster, Noah. American Dictionary of the English Language. 2 vols. 1828. Reprinted

1970. [LB3] {E2a/122} / [LB3] {E2a/247}

Websters Third New International Dictionary. 1961 ed. [LB3] {E2a/82}/ 1993 ed. [LB1]

{R833/28/93}

Sources and further reading

Cruse, Alan. Meaning in Language: An introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics. 2nd

ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. [LB4] {801/1130} / [RR] {801.2CR}

Hurford, James R., and Brendan Heasley. Semantics: A Coursebook. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1983. [LB3] {E1/335}

Whorf, Benjamin Lee. Language, Thought and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin

Lee Whorf. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 1956. [LB3] {E1/34}

56. The Simple Sentence, Compound and Complex Sentences

p. 61 a truly descriptive grammar would be comprehensive: For English, the best

examples are The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language and Longman

Grammar of Spoken and Written English (for details see above, in Reference

for Chapter 2); for Japanese, its Samuel E. Martins A Reference Grammar of

Japanese (for details see Reference below).

p. 62 as far as I know, nobody deviates from standard usage on this point: Although

in many lects (dialects, sociolects) them is used instead of, or as well as, those.

p. 71 The way that English genitive -s attaches itself to the end of a phrase shows

that its whats called a clitic.

p. 82 This book reads well is an example of whats called the middle intransitive

(where middle means something like halfway between active and passive).

p. 83 You may wonder how this example of whats claimed to be a long word from

Southern Tiwa is different from a sentence whose short words are separated by

Introduction to Linguistics / 6

hyphens instead of spaces. The answer is that this passes various tests for a

single word. If youre interested, see Chapter 4, Defining the Word-Form, of

Laurie Bauers Introducing Linguistic Morphology.

p. 89 She said that she wanted a red sports car a complement clause introduced

by a subordinator; other writers (such as Andrew Radford, in English Syntax)

call the latter a complementiser.

p. 91 The first two thirds of this page all the stuff about stones and drugs is confused. The resemblance between stones (small rocks) and Stones (Rolling

Stones) is distracting when we remember the Stones earlier use of drugs, and

there are some typos, and so forth. Instead, lets consider My students seem to

enjoy syntax. What this sentence means is that My students enjoy syntax

seems to be true. We can say It seems that my students enjoy syntax. Whats

the meaning of It in this sentence? Nothing at all. But English (unlike Japanese,

Spanish, etc.) demands an overt subject, so here English provides the meaningless (dummy or expletive) word It. The process by which My students enjoy

syntax is transformed into It seems that my students enjoy syntax is called raising. The verb seem is a raising predicate, as it raises the subject (My students)

of a lower clause to become the subject of the larger (matrix) clause.

p. 91 The rest of the sentences just provides context: Change provides to provide.

p. 91 For the green pair at the foot of the page, substitute: Bruce is eager to [Bruce]

see and is easy [not-Bruce] to see [Bruce]. Or for the former, Bruce is eager

for himself to see Cats, and for the latter, is easy for people other than Bruce

to see Bruce.

p. 92 He left after the meeting concluded, etc: CGEL regards the word after here as a

preposition.

pp. 9293

In the example here, driving across the plains is conventionally called a

dangling participle, which is something that is often criticized by prescriptivists.

p. 94 The division of relative clauses into restrictive and non-restrictive is a conventional one but Huddleston and Pullum call them integrated and supplementary

respectively (for their reason for rejecting restrictive, see A Students Introduction to English Grammar, p. 188).

p. 94 In fact the grammar check in Word has just put a green line. . . . Silly old Word;

theres nothing wrong with using the word that with a restrictive/integrated

relative clause (see A Students Introduction to English Grammar, p. 191).

p. 95 Possessor is a useful term, but remember that it doesnt necessarily imply

possession in any normal sense. I saw that student whose cold developed into

flu last month but if you have a cold you dont possess it.

p. 96 At the very foot of the page: the furlong is a measure of length (about 201

metres). Even in the English-speaking world (anglosphere) its obsolete, other

than in horse racing. Lester Piggott (b. 1935) was a jockey.

Introduction to Linguistics / 7

p. 98 When Winston Churchill was rebuked for this supposed solecism, he replied

That is the sort of English up with which I will not put. Forget about this. Keep

reading only if you wonder why Id tell you to forget it. Churchill was a British

prime minister, rebuked means told off, and solecism means mistake

(especially of language or logic). Churchills point here, and Blakes, is that this

is a very strange way to say This is the sort of English I wont put up with,

which has a preposition at the end and is idiomatic. The former sentence is just

one of many versions that appear in this legend; their general form is:

This/That is the sort/ kind/type of [noun phrase] up with which I will not put.

Whatever words are in it, the strangeness of this sentence does not show that

avoidance of stranding a preposition at the end of a sentence leads to strange

results. Briefly, this is because here its not a matter of a single word but

instead of two (up with). For details, see Geoffrey K. Pullum, A Churchill story

up with which I will no longer put, Language Log, 8 December 2004,

http://snipurl.com/not-put-cheating . (Incidentally, although Churchill is widely

reported to have written this, or something like it, its very unlikely that he did

so. See Benjamin G. Zimmer, A misattribution no longer to be put up with,

Language Log, 12 December 2004, http://snipurl.com/not-put-strand .)

p. 101

In Q2: Red Rum is running at Aintree: Red Rum was a horse that was famous

in the mid 1970s; Aintree is the name of a famous racetrack near Liverpool.

p. 102

In Q8: earn a pedants censure: this means be criticized by a language

prescriptivist (a language maven)

Reference

Martin, Samuel E. A Reference Grammar of Japanese. Rev. ed. Rutland, Vt.: Tuttle,

1988. [LB4] {815/2}

Trask, R. L. A Dictionary of Grammatical Terms in Linguistics. London: Routledge,

1996. [RR] {801.5/TR}

Trask, R. L. Dictionary of English Grammar. London: Penguin, 2004. [CR] {835/TR}

Sources and further reading

Bauer, Laurie. Introducing Linguistic Morphology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C. Georgetown University Press, 2003. [RR] {801.5/BA}

Brjars, Kersti, and Kate Burridge. Introducing English Grammar. London: Arnold,

2001. [CR] {835/80}

Brinton, Laurel J. The Structure of Modern English: A Linguistic Introduction. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2000. [LB4] {835/163}

Comrie, Bernard. Language Universals and Linguistic Typology. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 1989. [LB4] {801/130}

Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey K. Pullum. A Students Introduction to English

Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. [CR] {835/HU}

Radford, Andrew. English Syntax: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2004. [RR] {835.1/RA} / [LB4] {835/162}

Swan, Michael. Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. <*> [CR] {835/SW}

Introduction to Linguistics / 8

Tallerman, Maggie. Understanding Syntax. 2nd ed. London: Hodder Arnold, 2005.

[RR] {801.5/TA}

Whaley, L. J. Introduction to Typology. J. :

: , 2006. [L1] {901/WH}

7. Using Language

p. 106

sonuvabitch: i.e. son of a bitch. This is whats called eye dialect, deliberately

incorrect spelling to suggest that whats said is nonstandard without actually

demonstrating how its nonstandard. (In this example, son and a bitch are

preserved, but of becomes uv. Yet in standard English, of would here be pronounced /v/, and uv is a straightforward way to represent this in the normal

alphabet.

p. 108

It was Viduka who won the game for us and The one who won the game for

us was Viduka are examples of what are called cleft and pseudo-cleft sentences

respectively.

p. 114

Second line: As an example of including too much information, take the

following. . . . This example is confusing, and I suggest that you skip it, which

means that you can skip this explanation as well. Keep reading only if youre

interested. Blake says that I would have thought most people are familiar with

the fact that [Porgy and Bess] is for an entirely black cast. . . . Not exactly.

Just as many of Shakespeares historical plays are for white characters, Porgy

and Bess is for black characters. But just as these plays by Shakespeare can be,

and are, played by casts (groups of actors) of all colors (even within Britain,

where theres no shortage of white people), Porgy and Bess can be, and is,

played by casts (groups of actor/singers) of all colors. Still, its likely that

Glyndebourne (an opera company) was particularly keen to employ black

people. Moreover, the singer might have thought that her friend (more used to

less popular works) might benefit from a subtle reminder of what Porgy and

Bess is. Anyway, I dont think that it violates the principle/maxim of quantity for

the singer to say this.

p. 119

Third line: to bags the next turn: Schoolboy English; bags (or bag in my

English): is informal for say [you] want [something] before anybody else does.

Sources and further reading

Bloor, Thomas, and Meriel Bloor. The Functional Analysis of English: A Hallidayan

Approach. 2nd ed. London: Arnold, 2004. [LB4] {835/167}

Grice, H. Paul. Logic and Conversation. In Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3, Speech

Acts, ed. by Peter Cole and Jerry L. Morgan. New York: Academic Press 1975.

[LB4] {835/16/3} Available at http://snipurl.com/grice-lc

Widdowson, H. G. Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. <*>

[CR] {801.03/WI}

Yule, George. Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. <*> [CR] {801/YU} /

[L1] {801/YU}

Introduction to Linguistics / 9

8. Phonetics

Tips for typing IPA characters: You dont need any special phonetic font. Instead,

just use a large font that includes IPA characters in addition to others. Here, I am using

Bitstream Vera Sans, which can legally be downloaded free

( http://www.gnome.org/fonts/ ). DejaVu, which is based on Vera, is much bigger and

can also legally be downloaded free ( http://dejavu.sourceforge.net/ ). Lucida Sans

Unicode and Lucida Grande (which come with Windows and Mac OS X respectively)

also include IPA characters, and other fonts that may already be in your computer may

do as well. Fonts can expand over time: when I started typing this, I found that

phonetic characters I typed into it using one computer would not appear on another

computer: this was because the version of Bitstream Vera Sans installed in the second

computer was older than the one installed in the first and didnt include as many

characters.

p. 126

p. 129

rhyme: Other writers spell this rime.

There is an American version of IPA. No there is not. Take this to mean There

is a de facto American alternative to IPA. This alternative has various names.

Wikipedia calls it Americanist phonetic notation and the article on this is good

(at least when not vandalized, e.g. http://snipurl.com/american-phonetic ). In

their Phonetic Symbol Guide, Pullum and Ladusaw refer to it as American

usage. Briefly, its a phonetic alphabet that was designed by Americans, and

primarily for Americanists (people studying native American languages, as

briefly listed on p. 210); it had some advantages over IPA until computers, Unicode and large fonts made it easy for us to type such IPA characters as .

Now it seems rather pointless, although many American linguists remain

attached to it and you may have to read some paper or book that uses it.

p. 129 (foot of the page) As youll read on p. 139, there are languages with rounded

front vowels.

p. 130

Received Pronunciation: Here, received means generally accepted. This

use of the word is rather unusual, and is associated with RP and The Dictionary

of Received Ideas, the standard English title for Flauberts satirical work Le

Dictionnaire des ides reues ().

p. 130

This distinction between kinds of English in which the r of hard (a) is and

(b) isnt pronounced is the distinction between (a) rhotic and (b) non-rhotic

kinds of English: see p. 136.

p. 130

In General American [a] [is also used] for words like cot and hog, which

have [] in RP. I think these should be [a] and not [] respectively.

p. 134

There are two th-sounds in English made by putting the tip of the tongue

between the upper and the lower teeth. For most speakers of RP, the tongue

does not go between the teeth (see Gimsons Pronunciation of English, 6th ed.,

pp. 18384).

p. 135

In IPA the symbol . . . upside down-r [is used] for the sound found in the

mainstream pronunciation of words like Garry: This is written [] and its

Introduction to Linguistics / 10

better called turned r.

p. 139

The clicks [ | ! ], together with much else, are described in Peter

Ladefogeds Vowels and Consonants (see Sources and further reading below)

and are demonstrated on the CD-ROM that comes with that book.

Reference

Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the

International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

[RR] {801.1/IN}

Pullum, Geoffrey K., and William A. Ladusaw. Phonetic Symbol Guide. 2nd ed. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1996. [RR] {801.1/PU} / [LB4] {R801/124/2}

Trask, R. L. A Dictionary of Phonetics and Phonology. London: Routledge, 1996.

[RR] {801.1/TR}

Sources and further reading

Carr, Philip. English Phonetics and Phonology: An Introduction. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1999. [CR] {831.1/CA} / [LB4] {831/58}

Catford, J. C. A Practical Introduction to Phonetics. 2nd ed. Oxford Oxford University

Press, 2001. [RR] {801.1/CA}

Cruttenden, Alan, ed. Gimsons Pronunciation of English. 6th ed. London: Hodder

Arnold, 2001. [RR] {831.1/GI} / [LB4] {831/506} {L1} {831/GI}

Ladefoged, Peter. A Course in Phonetics. 5th ed. N.p.: Thomson Wadsworth, 2006.

[L1] {801.1/LA} With CD-ROM.

Ladefoged, Peter. Vowels and Consonants: An Introduction to the Sounds of Languages. 2nd ed. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2005. With CD-ROM. [RR] {801.1/LA} /

[LB4] {801/921/2}

fnetks: The Sounds of Spoken Language. (Alternative title Phonetics Flash Animation

Project; previous title Phonetics: The Sounds of English and Spanish.) University of

Iowa. The sounds of US English, Spanish, and German. (You must have Flash 7 or

higher plug-in to use this web site.) http://www.uiowa.edu/~acadtech/phonetics/ or

http://snipurl.com/iowa-ph

Roach, Peter. Phonetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. <*> [CR] {801.1/RO}

Roach, Peter. English Phonetics and Phonology: A Practical Course. 3rd ed. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2000. [CR] {831.1/RO}

Wells. J. C. What ever happened to Received Pronunciation? Medina and Soto, eds, II

Jornadas de Estudios Ingleses, Universidad de Jan, 1997. http://snipurl.com/wells-rp

or http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/wells/rphappened.htm

9. Phonology

p. 144

For a Japanese analogy, consider the sounds of in , and to

me, they sound like [m], [], and [n] respectively.

p. 147(in the box) an intervocalic /t/ pronounced by flicking the tongue up to the

alveolar ridge, with continuous voicing: such a flap is written []. This is close to

the sound of Japanese , although the latter is more correctly [].

Introduction to Linguistics / 11

p. 151 Table 9.1: Blake writes * for several initial consonant clusters that do occur

very occasionally in English, and even in the following notes (pp. 15152)

doesnt mention all of these. Try thinking of some!

p. 152 End of note (v): They presumably aim at [s] and dont notice when it comes out

as []. If its a majority, it seems likely that the pronunciation is regarded as

correct. Barry Blake says in email that he has talked with people who believe

they are saying [s] but are actually saying [].

p. 153 near the foot: since we are all persons of the highest probity: since we are all

very decent people, which rules out an alternative interpretation of /ltrz/. (I

shant tell you what that alternative is; have fun working it out for yourselves!)

p. 155

p. 155

p. 159

alpha, bravo, Charlie: This is the international radiotelephony spelling alphabet.

Clearly something is missing: For missing, read different.

Note that [c] in [laca] represents a voiceless palatal stop: which means that

its something between [t] and [k].

Reference

Trask, R. L. A Dictionary of Phonetics and Phonology. London: Routledge, 1996.

[RR] {801.1/TR}

Sources and further reading

Carr, Philip. English Phonetics and Phonology: An Introduction. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1999. [CR] {831.1/CA} / [LB4] {831/58}

Roach, Peter. English Phonetics and Phonology: A Practical Course. 3rd ed. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2000. [CR] {831.1/RO}

10. Writing

p. 164

the rebus principle: Think of , such as the way that was first thought

of (or in Japan and in China and Korea).

p. 164

mainly by adding a determinative: Think of the commonest kind (,

xngshngz) of compound Chinese characters; Blake discusses these on p. 171.

p. 169

syllabic script: Something like Japanese kana or Korean hangul.

p. 172

syllables in which the coda is the same as the onset of the succeeding

syllable: If youre wondering what to call this thing written with little , its a

geminate.

p. 175

Slough (the place and the Slough of Despond in Pilgrims Progress): In

case your command of IPA is rusty, Slough rhymes with cow. The word slough

may be archaic and perhaps obsolete, but its an old word meaning bog.

Slough is also a town west of London. The Slough of Despond is a fictional bog

in the 17th-century religious work The Pilgrims Progress (usual Japanese title

Introduction to Linguistics / 12

). Despond is now obsolete; it used to mean misery. (The related word

despondency is still used.)

Sources and further reading

Campbell, George L. Handbook of Scripts and Alphabets. New York: Routledge, 1997.

[LB4] {801/649}

Coulmas, Florian. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford: Blackwell,

1996. [LB4] {R801/576}

Coulmas, Florian. Writing Systems: An Introduction to their Linguistic Analysis.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. [LB4] {801/998}

Coulmas, Florian. The Writing Systems of the World. Oxford: Blackwell, 1989.

[LB4] {801/186}

Daniels, Peter T., and William Bright. The Worlds Writing Systems. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1996. [LB4] {801/569}

Marcus, J. Mesoamerica: Scripts. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. 2nd ed.,

ed. Keith Brown 14 vols. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006. [LB1] {R803/28}

11. Varieties

p. 183

Scottish English is a dialect within Britain: Perhaps. What Blake calls Scottish

English is more often called Scots (while Scottish English is more often used to

mean a fairly standardized, Scotland-wide form of English). To give you a taste,

I quote the top page of lallans.co.uk:

This wabsteid rowes swackest wi Realplayer dounladit an set as defaut for pleyin

MP3 file types. Gin ye need this saftware the link til the corrie o this jot will tak ye

til thair wabsteid. See an howk for the free pleyer that dis aa yell need.

[This] website runs most smoothly with Realplayer downloaded and set as default

for MP3 file types. If you need this software the link at the left of this note will take

you to their website. Remember to search for the free player that does everything youll need.

Of course the division between dialect and language is rather arbitrary, but

youll probably agree that Scots is very different from standard English. And

since 2002 it has been a protected language under the European Charter for

Regional or Minority Languages.

p. 187

In Britain and the Commonwealth the Oxford English Dictionary is the accepted standard [for spelling]: No it isnt. In English, many verbs can be written

either -ise or -ize (and nouns, either -isation or -ization). In the US, -ize (-ization)

is normal. In Britain, both are used, but -ise (-isation) is much commoner. The

Oxford English Dictionary uses -ize (-ization). My impression is that theres no

single authority for spelling in Britain.

p. 191

a professional linguist might point out that AAVE has its own system: They

can and do. For a short and simple piece, see Pullum, Why Ebonics is no joke.

There are several good books; Greens African American English is particularly

Introduction to Linguistics / 13

good.

p. 194 (foot of the page): The following could have been written by Bridget Jones:

Bridget Jones is the fictional author of a regular column in the British newspaper

The Independent; the material has been turned into books and films.

p. 198

Dutch treat: I find this explanation hard to believe, partly because treat

doesnt rhyme with any relevant noun (meal, dinner, feast, etc), and

partly because of the long history within English of non-rhyming, pejorative uses

of Dutch (Dutch courage, Dutch wife, etc). The Oxford English Dictionary

partly agrees with me, and finds the earliest use of Dutch treat to be

American, not British.

p. 199

In Switzerland, for instance, High German is the high form and Swiss German the low form. Change the first two words to In much of Switzerland. (In

some parts of Switzerland, a form of French thats close to the standard is used

for almost all purposes.) If youre interested, there are further complexities in

Switzerland. For example, somebody living in the east may routinely switch

among High German (i.e. standard German), the local form of Swiss German,

and also the local form of Romansh (a language thats only spoken by a small

minority of Swiss people). And for business this person may on occasion have to

use French or Italian or both.

Sources and further reading

Britain, David, ed. Language in the British Isles. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2007. [RR] {802.33/BR}

Cameron, J. Gender. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. 2nd ed., ed. Keith

Brown. 14 vols. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006. [LB1] {R803/28}

Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. [RR] {830.36/CR} /

[LB4] {R830/121/2}

Eckert, Penelope, and Sally McConnell-Ginet. Language and Gender. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2003. [LB4] {801/962}

Green, Lisa J. African American English: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2002. [LB4] {830/265} / [TL] {830/90}

Holmes, Janet. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. London: Longman, 1992. [L1] {801/

HO}

Kramsch, Claire. Language and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. <*>

[CR] {801.03/KR} / [TL] {807/53}

Pullum, Geoff. Why Ebonics is no joke. Lingua Franca. Australian Broadcasting

Corporation, 17 October 1998. http://snipurl.com/aave-no-joke or

http://www.abc.net.au/rn/arts/ling/stories/lf981017.htm

Romaine, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1994. [TL] {801/159}

Spolsky, Bernard. Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. <*>

[CR] {801.03/SP} / [TL] {801/545}

Trudgill, Peter. The Dialects of England. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

[LB4] {838/15/2}

Introduction to Linguistics / 14

Trudgill Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed.

London: Penguin, 2000. [L1] {801/TR}

Trudgill, Peter, and Jean Hannah. International English: A Guide to Varieties of

Standard English. 4th ed. London: Arnold, 2002. [L1] {838/TR} / [LB4] {838/44/4}

Wolfram, Walt, and Natalie Schilling-Estes. American English: Dialects and Variation.

Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1998. [LB4] {838/66}

12. Language Change

p.205

I think that Blake understates the difficulty that most present-day native

speakers of English face in understanding Shakespeare and Chaucer.

p. 206

Its true that Anglosaxon languages replaced languages that are commonly

called Celtic. However it seems that this replacement happened in a way that

was very different from the story thats commonly told and that Blake summarizes. If youre interested, see Oppenheimers writing, listed below.

pp. 208, 211

In his third list item (The Turkic family . . .), Blake mentions an Altaic

family; at the end of his list he mentions the isolates Japanese, Korean and

Basque. Some linguists believe that Japanese and Korean are linked in the Altaic

family. Although the distinction between dialect and language is vague, many

linguists regard Ryukyuan () as languages rather than dialects, and if they

are then together with Japanese theyre in the Japonic family.

p. 208

p. 213

When writing about the languages in the Caucasus, Blake says that three

families have typological similarities. (He mentions typology again on p. 278.)

Typological similarities are similarities of form, regardless of origin. Consider

Chinese and English: they are different in many ways and they are not members

of the same family, but typologically they are similar in that they both have

SVO (subjectverbobject) as the standard order.

in actual osculation: in actual kissing

p. 215

Perhaps phenomena and criteria are starting to become used as singular

which would not be surprising, in view of agenda, data, and opera but they

havent arrived there yet. Use phenomenon and criterion for the singular if you

dont want people to laugh at you.

p. 218

There goes the neighborhood: For Here/There + come/go see CGEL p. 1390.

(For There stood the killer, etc, see CGEL pp. 14021403 on the presentational

construction.)

p. 218

we still put an auxiliary in second position after certain adverbs: These adverbs are what CGEL calls absolute negators (such as never) and approximate

negators (such as scarcely and rarely) but this only works for clausal negation;

see CGEL pp. 78889.

p. 219

on the face of, at the bottom of, and at the back of, which can be considered compound prepositions: Its true that they are often called compound

Introduction to Linguistics / 15

prepositions (or phrasal prepositions), but they are not prepositions. See

Geoffrey K. Pullum, Phrasal prepositions in a civil tone, Language Log, 3

February 2005, http://snipurl.com/phrasal-prep

p. 220

AC/DC: Originally, AC meant alternating current and DC meant direct

current. AC/DC means bisexual, but strangely neither AC nor DC is used by

itself to mean heterosexual or homosexual. (Moreover, the bisexual usage is

now uncommon: the word seems to have been usurped by the name of a rock

group.)

p. 220

Spam, for example, formerly referred to canned meat. . . . Even now,

Spam is the registered trademark of Hormel Foods Corporation for its brand of

luncheon meat; spam (small s) is indeed used for junk mail, and unusually

we know how this extension of meaning came to happen (but Ill let you find

this out for yourselves).

p. 221

Common itself has gone downhill as in Theyre quite common. To me,

the use of common in the dismissive Her manners are very common seems oldfashioned. Theres nothing pejorative about iPods are common among students,

and I suspect that common has experienced amelioration.

p. 221

Urbane [. . .] came to mean sophisticated: Yes, but only in the presentday meaning of sophisticated, which itself has undergone considerable amelioration since its roots in sophistry.

pp. 22122 Although awful, terrible and the others do indeed mean very bad, the

adverbs from some of them can be used as simple intensifiers.

p. 224

You might have trouble with the Shakespeare quotation. First, the planet

Neptune hadnt been discovered in Shakespeares day, and here Neptune is

instead the Roman god of the sea. Heres my attempt at a translation into

modern English: Will all great Neptunes ocean wash this blood clean from my

hand? No, this hand of mine will instead turn the many seas pink, making the

green seas red. (The word incarnadine is hardly ever used now, but when it is

used it means red rather than pink.)

p. 225

To spare you the embarrassment that might arise if you asked a Spanishspeaking friend, Ill point out that cojones are balls (i) in the male, anatomical

sense (e.g. He was kicked in the balls; a use that itself is metaphorical), and

(ii) also in the metaphorical sense that arises from that (e.g. Hes really got

balls). And now cojones (not always spelled correctly) is used in the metaphorical sense within English too: Anyone who thinks Bill Clinton doesnt have the

cajones [sic] to speak up needs corrective lenses (Jayne Lyn Stahl, Cojones

and Conservative Hit Jobs!, The Huffington Post, 25 September 2006,

http://snipurl.com/c-jones .)

p. 227

This has lead to the notion that. . . . A simple typo. Not lead (which would be

present tense) but led.

p. 228

see the Prodigal Son example above: This is on p. 214.

Introduction to Linguistics / 16

Reference

Campbell, George L. Compendium of the Worlds Languages. 2nd ed. 2 vols. London:

Routledge, 2000. {801/204/2}

Comrie, Bernard. The Worlds Major Languages. London: Croom Helm, 1987.

[LB3] {801/12}

Comrie, Bernard, et al., eds. The Atlas of Languages: The Origin and Development of

Languages Throughout the World. New York: Facts on File, 2003. [RR] {801.8/CO} /

[LB4] {801/1008}

Trask, R. L. The Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000. [RR] 803.3/TR}

Sources and further reading

Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay? 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2001. [LB4] {801/899}

Austin, Peter K. One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost. University of

California Press, 2008. [LB4] {801/1254}

Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More than 400

Languages. Rev. ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004. [CR] {803/DA}

Oppenheimer, Stephen. Myths of British ancestry. Prospect, October 2006.

http://snipurl.com/celt-myth1

Oppenheimer, Stephen. Myths of British ancestry revisited. Prospect, June 2007.

http://snipurl.com/celt-myth2

Price, Glanville. Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998.

[LB4] {R803/20}

Pyles, Thomas, and John Algeo. The Origins and Development of the English Language.

3rd ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982. [TL] {830/45}

Schendl, Herbert. Historical Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. <*>

[CR] {801.02/SC} / [L1] {801/SC}

13. Language Acquisition

p. 234

is exposed to repeated tokens of [pa]: is played a recording of [pa pa pa pa

pa pa pa pa]

p. 245

Followers of Chomsky have posited that there are innate principles of Universal Grammar (UG) that constrain and guide the child. The idea that there

are innate principles, or an innate instinct to learn language, is called innatism

or nativism.

p. 246

the first twelve years constitutes a critical or sensitive period: This is usually

called the Critical Period (CP). Evidence suggests that there is no simple cut-off

point for a single CP, and that instead the CP ends earlier for phonology than it

does for syntax.

p. 247

The ice-cream cost three dollars There has long been discussion among linguists about the reason why sentences with verbs of measure (cost, measure,

etc.) cant be put in the passive. Blake says one needs to consider discourse

Introduction to Linguistics / 17

principles. Another reason is given by Frederick Newmeyer, who says (Language Form and Language Function, pp. 18687) that three dollars here is not

an object but instead a predicate nominative, like a young lady in Your

daughter has become a young lady. You cant say *A young lady has been

become by your daughter, and in the same way you cant say *Three dollars is

cost by the ice cream.

p. 249

La plume de ma tante: a phrase that is commonly given as an example when

people make fun of unrealistic language exercises. (The stereotype of an absurd

English sentence is My postilion has been struck by lightning; this is confidently

stated to have appeared in this or that kind of textbook or phrasebook, but nobody has yet actually found it, so its almost certainly apocryphal.)

Sources and further reading

Aitchison, Jean. The Articulate Mammal: An Introduction to Psycholinguistics.

: : , 1985. [LB3] {E1/477}

Bavin, E. L. Syntactic development. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. 2nd

ed., ed. Keith Brown. 14 vols. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006. [LB4] {R803/28}

CHILDES. http://childes.psy.cmu.edu/

Ellis, Rod. Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. <*>

[CR] {807/EL}

Fletcher, Paul, and Brian MacWhinney. The Handbook of Child Language. Oxford:

Blackwell, 1995. [LB4] {801/534}

Lieven, E. Language development: An overview. Encyclopedia of Language and

Linguistics. 2nd ed., ed. Keith Brown. 14 vols. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006.

[LB4] {R803/28}

Lightbown, Patsy M., and Nina Spada. How Languages Are Learned. 3rd ed. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2006. [CR] {807/LI}

Lust, Barbara. Child Language: Acquisition and Growth. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2006. [RR] {801.04/LU}

Newmeyer, Frederick. Language Form and Language Function. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT,

1998. [LB4] {801/1236}

Peccei, Jean Stilwell. Child Language: A Resource Book for Students. Abingdon, Oxon:

Routledge, 2006. [RR] {807/PE}

Pinker, Steven. The Language Instinct. New York: Harper Perennial, 1994.

[LB4] {801/583} The Language Instinct: The New Science of Language and Mind.

London: Penguin. [CR] {801.01/PI}

Scovel, Thomas. Psycholinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. <*>

[CR] {801.04/SC} / [TL] {801/546}

Below is the sequence of papers with arguments for and against Chomskys position.

Its a learned dispute between on the one hand Noam Chomsky and the biologists

Marc Hauser and Tecumseh Fitch, and on the other the psychologist Steven Pinker and

the linguist Ray Jackendoff. (Although these people shouldnt be compartmentalized so

quickly: Pinker, for example, has written books about language.) Youll probably find

the papers difficult to understand (and if you dont find them difficult to understand, I

fear that you will have found this course shallow and boring). Still, Blake does recom-

Introduction to Linguistics / 18

mend this exchange of views and the material is worthwhile.

1. Marc D. Hauser, Noam Chomsky, and W. Tecumseh Fitch. 2002. The language

faculty: What is it, who has it, and how did it evolve? Science 298 (2002), 156979.

Available at http://snipurl.com/fl-what-who-how

2. Steven Pinker and Ray Jackendoff. The faculty of language: Whats special about

it? Cognition 95 (2005), 201236. Available at http://snipurl.com/fl-what

3. W. Tecumseh Fitch, Marc D. Hauser, and Noam Chomsky. The evolution of the

language faculty: Clarifications and implications. Cognition, 97 (2005): 179210.

Available at http://snipurl.com/evol-lf

4. Ray Jackendoff and Steven Pinker. The nature of the language faculty and its implications for evolution of language (Reply to Fitch, Hauser, and Chomsky). Cognition

97 (2005), 21125. Available at http://snipurl.com/nlf-jp

14. Language Processing: Brains and Computers

p. 255

p. 258

Blake quotes Wikipedia, which I find alarming. (On p. 268 he also says he

has relied on it for what he writes on mondegreens.) The Wikipedia article cites

H. Goodglass and N. Geschwind, Language disorders, in E. Carterette and M.

P. Friedman, eds, Handbook of Perception: Language and Speech 7 (New York:

Academic Press, 1976). He should really have checked that, and, if he found it

was correct, cited it (perhaps with a note about Wikipedia).

on your internal video: in your imagination

p. 259

So youre getting calls from the other side, eh? Here, the other side means

the world of the dead.

p. 259

when the goats are lambing: The verb to lamb is usually used in just this way

(but for sheep). Likewise, foal and calve are used for horses and cows respectively. Lambs are to sheep what kids are to goats, so you might think that when

the goats are kidding would do the job. Sure enough, kid does have this meaning. However, the other meaning of the verb to kid The mayor of some suburb

of Anchorage for veep? You must be kidding! is so strong that it seems to

have blocked this out.

p. 260

The stories about Spooners spoonerisms are hard to believe. What might

the context be for weary benches? Most of these stories are apocryphal (although they are enjoyable).

p. 261

If mondegreens look interesting, you should enjoy

http://www.kissthisguy.com

p. 265

cepstrum: Even if the mathematics doesnt interest you, you can see

examples of quefrency alanysis via cepstrum in Gessl, Cepstrum analysis.

Sources and further reading

Gessl, Guido. Cepstrum analysis. Institute for Measurement Technology, Johannes

Kepler University of Linz. 2004. (PDF file, over 500kB) http://snipurl.com/cepstrum

Introduction to Linguistics / 19

Ladefoged, Peter. A Course in Phonetics. 5th ed. N.p.: Thomson Wadsworth, 2006.

[L1] {801.1/LA} With CD-ROM.

Pratt, N., and H. A. Whitaker. Aphasia syndromes. Encyclopedia of Language and

Linguistics. 2nd ed., ed. Keith Brown. 14 vols. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006.

[LB4] {R803/28}

15. The Origin of Language

p. 271

communicating with their conspecifics: Communicating with other animals of

the same species (dogs communicating with dogs, rats communicating with

rats, etc)

Sources and further reading

Aitchison, Jean. The Seeds of Speech: Language Origin and Evolution. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2003. [LB4] {801/630}

Burling, R. The Talking Ape: How Language Evolved.

: : , 2007. {L1] {801/BU}

Jackendoff, Ray. Foundations of Language: Brain, Meaning, Grammar, Evolution.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. Chap. 8. [LB4] {801/1082}

Todd, Loreto. Pidgins and Creoles. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 1990. [B4] {801/200/2}

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Tools of Argument How The Best LawyersDocument1 pageThe Tools of Argument How The Best LawyersTaga Bukid100% (1)

- Ernst Junger - Copse 125 - Full Text - Basil Creighton 1930Document146 pagesErnst Junger - Copse 125 - Full Text - Basil Creighton 1930Bogdan Costea0% (1)

- Wotw Student WorkbookDocument28 pagesWotw Student Workbookapi-317825538Pas encore d'évaluation

- Similitude & AssimilationDocument1 pageSimilitude & AssimilationMariano Saab100% (1)

- Novels For Students Vol 1-Hemingway, Austen, Hawthorne, Huck Finn PDFDocument365 pagesNovels For Students Vol 1-Hemingway, Austen, Hawthorne, Huck Finn PDFKelemen Zsuzsánna100% (5)

- Accessibility LinksDocument3 pagesAccessibility LinksJanine Rose LumanagPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3 - Literary TheoriesDocument7 pagesChapter 3 - Literary TheoriesApenton Mimi100% (1)

- Sample Stylistic AnalysisDocument49 pagesSample Stylistic AnalysisReuel RavaneraPas encore d'évaluation

- MRW A Maranao Dictionary-Front 1996 PDFDocument31 pagesMRW A Maranao Dictionary-Front 1996 PDFJohairah YusophPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 1: Literature and Literary TheoryDocument29 pagesCHAPTER 1: Literature and Literary TheoryHturamla Ortsaced PacalPas encore d'évaluation

- Genre Analysis ActivityDocument3 pagesGenre Analysis ActivityNoel Philip100% (1)

- Differences Between Spoken and Written DiscourseDocument19 pagesDifferences Between Spoken and Written Discoursehugoysamy29Pas encore d'évaluation

- محاضرات نحو تحويلي رابع اداب انكليزيDocument112 pagesمحاضرات نحو تحويلي رابع اداب انكليزيZahraa KhalilPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Project (Fire & Ice)Document18 pagesResearch Project (Fire & Ice)محمد سعید قاسم100% (1)

- Textual and Reader-Response StylisticsDocument10 pagesTextual and Reader-Response StylisticsDivine ArriesgadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Phatic TokenssDocument21 pagesPhatic TokenssFatima QadeerPas encore d'évaluation

- Handouts RZM, P. 1: Quantity Exhorts Speakers To "Make (Their) Contribution As Informative As Is Required ForDocument5 pagesHandouts RZM, P. 1: Quantity Exhorts Speakers To "Make (Their) Contribution As Informative As Is Required ForAyubkhan Sathikul AmeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng 111 - Children and Adolescent LiteratureDocument7 pagesEng 111 - Children and Adolescent LiteratureMa. Cecilia BudionganPas encore d'évaluation

- By Archibald Macleish: Ars PoeticaDocument3 pagesBy Archibald Macleish: Ars PoeticaYasmin G. BaoitPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 11: American Structuralism: Leonard Bloomfield (1887 - 1949) Got Interested in Language From A ScientificDocument8 pagesLecture 11: American Structuralism: Leonard Bloomfield (1887 - 1949) Got Interested in Language From A ScientificGiras Presidencia100% (1)

- 1 Stylistics (2) Master 2Document47 pages1 Stylistics (2) Master 2Safa BzdPas encore d'évaluation

- General Notes On StylisticsDocument14 pagesGeneral Notes On StylisticsLal Bux SoomroPas encore d'évaluation

- Theoretical Foundations of Language and LitDocument10 pagesTheoretical Foundations of Language and LitJawwada Pandapatan MacatangcopPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On The Emergent PeriodDocument2 pagesNotes On The Emergent PeriodReinopeter Koykoy Dagpin LagascaPas encore d'évaluation

- Introducing Stylistics 1Document25 pagesIntroducing Stylistics 1Bimbola Idowu-FaithPas encore d'évaluation

- Contrastive Studies-History and DevelopmentDocument17 pagesContrastive Studies-History and DevelopmentДрагана Василиевич100% (1)

- 2022 Course Syllabus in LED 62 Teaching and Assessment of Literature StudiesDocument10 pages2022 Course Syllabus in LED 62 Teaching and Assessment of Literature StudiesTejano MaePas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To StylisticsDocument20 pagesIntroduction To StylisticsAbs Villalon100% (1)

- Phonology.1 PHONEMEDocument16 pagesPhonology.1 PHONEMEMOHAMMAD AGUS SALIM EL BAHRI100% (3)

- StylisticsDocument4 pagesStylisticsWahid ShantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To StylisticsDocument7 pagesIntroduction To StylisticsEd-Jay RoperoPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1 Nature of LiteratureDocument6 pagesModule 1 Nature of LiteratureRoldan MapePas encore d'évaluation

- Behaviorist TheoryDocument2 pagesBehaviorist TheoryJenipher Abad100% (1)

- Handouts On RenaissanceDocument52 pagesHandouts On RenaissanceMary AnnPas encore d'évaluation

- Discussion Paper 2 - Pedagogical StylisticsDocument2 pagesDiscussion Paper 2 - Pedagogical StylisticsScooption AdtragePas encore d'évaluation

- English & American Literature: Practice Test in EnglishDocument5 pagesEnglish & American Literature: Practice Test in EnglishApple Mae CagapePas encore d'évaluation

- Literary Analysis:: Structuralist PerspectiveDocument17 pagesLiterary Analysis:: Structuralist PerspectiveJosh RoxasPas encore d'évaluation

- COURSE SYLLABUS Teaching LiteratureDocument2 pagesCOURSE SYLLABUS Teaching Literaturesrregua63% (8)

- Exercise 1: I. Choose The Best Answers To Complete The SentencesDocument3 pagesExercise 1: I. Choose The Best Answers To Complete The SentencesNurhikma AristaPas encore d'évaluation

- PPTDocument31 pagesPPTHaikal Azhari100% (3)

- Mga Anak NG ArawDocument2 pagesMga Anak NG ArawDivine Grace Alejo AcobaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Literature Periods (Gen Ed Reviewer 2017)Document7 pagesPhilippine Literature Periods (Gen Ed Reviewer 2017)glydel tricia tapasPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 The Scope of LinguisticsDocument3 pages1 The Scope of LinguisticsPinkyFarooqiBarfiPas encore d'évaluation

- Commmunicative Language Teaching (CLT) : I-IntroductionDocument6 pagesCommmunicative Language Teaching (CLT) : I-IntroductionHajer MrabetPas encore d'évaluation

- LIT 127.7 J Martin Third World Lit SyllDocument5 pagesLIT 127.7 J Martin Third World Lit SyllshipwreckedPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Solve Morphology ProblemsDocument4 pagesHow To Solve Morphology ProblemsUmi0% (1)

- BSEE 21 (Introduction To Linguistics) Course SyllabusDocument3 pagesBSEE 21 (Introduction To Linguistics) Course SyllabusJiyeon ParkPas encore d'évaluation

- FINAL Exam Teaching and Assessment of GrammarDocument2 pagesFINAL Exam Teaching and Assessment of GrammarReñer Aquino BystanderPas encore d'évaluation

- LLD 311 Cel Discourse GrammarDocument41 pagesLLD 311 Cel Discourse GrammarMichael John Jamora100% (1)

- Ling 131 - A Brief History of StylisticsDocument1 pageLing 131 - A Brief History of StylisticsBocoumPas encore d'évaluation

- STYLISTICSDocument14 pagesSTYLISTICSZara Iftikhar100% (1)

- Literary GenreDocument4 pagesLiterary GenreRubz JeanPas encore d'évaluation

- Functional Stylistics of The Modern English LanguageDocument13 pagesFunctional Stylistics of The Modern English LanguageLamy MoePas encore d'évaluation

- Models of Teaching LiteratureDocument7 pagesModels of Teaching LiteratureEdward James Fellington100% (1)

- The Physical Adaptation SourceDocument4 pagesThe Physical Adaptation SourceRubén Zapata50% (2)

- Qualitative Corpus AnalysisDocument11 pagesQualitative Corpus Analysisahmed4dodiPas encore d'évaluation

- Medieval and Renaissance LiteratureDocument6 pagesMedieval and Renaissance LiteratureDemis ImmortalPas encore d'évaluation

- Americanism SDocument26 pagesAmericanism SAni MkrtchyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Stylistics and Discourse Analysis Module 2-The Literary Norms DescriptionDocument6 pagesStylistics and Discourse Analysis Module 2-The Literary Norms DescriptionJazlyn CalilungPas encore d'évaluation

- Stylistics and Discourse Analysis Syllabus DGPDocument8 pagesStylistics and Discourse Analysis Syllabus DGPJsaiii HiganaPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature and Its Literary TheoriesDocument7 pagesLiterature and Its Literary Theoriesdanaya fabregasPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study Guide for Vishnu Sarma's "The Mice that Set the Elephants Free"D'EverandA Study Guide for Vishnu Sarma's "The Mice that Set the Elephants Free"Pas encore d'évaluation

- AUTHORS: Bieswanger, Markus Becker, Annette TITLE: IntroductionDocument7 pagesAUTHORS: Bieswanger, Markus Becker, Annette TITLE: IntroductionDinha GorgisPas encore d'évaluation

- A Linguistics Reading ListDocument7 pagesA Linguistics Reading ListMarcos GonçalvesPas encore d'évaluation

- B.tech Project Report ManualDocument18 pagesB.tech Project Report ManualUdith kumar narayananPas encore d'évaluation

- (School of Chess Excellence 3 - Progress in Chess Vol. 9.) Dvorečkij, Mark Izrailevič - Neat, Kenneth Philip - Strategic Play-Olms (2002) PDFDocument117 pages(School of Chess Excellence 3 - Progress in Chess Vol. 9.) Dvorečkij, Mark Izrailevič - Neat, Kenneth Philip - Strategic Play-Olms (2002) PDFBreno Sniker100% (1)

- Howard ShoreDocument6 pagesHoward ShorevaleeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Jerome RobbinsDocument24 pagesJerome RobbinslauralozconPas encore d'évaluation

- Marriage: The Next Life Series, Study 05Document1 pageMarriage: The Next Life Series, Study 05Haw Ciek ThingPas encore d'évaluation

- Essays-Claim Evidence CommentaryDocument2 pagesEssays-Claim Evidence Commentaryapi-469059724Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1000 English Verbs FormsDocument30 pages1000 English Verbs FormsSannan Ali100% (2)

- Betts - Dating The ExodusDocument14 pagesBetts - Dating The Exodusrupert11jgPas encore d'évaluation

- Fornication, Adultery and Christian MarriageDocument5 pagesFornication, Adultery and Christian MarriagesternagainPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1 - The Big PictureDocument14 pagesLesson 1 - The Big PictureJohnny ThompsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancestros Michelle Margules Cohen: Producido Por MyheritageDocument1 pageAncestros Michelle Margules Cohen: Producido Por Myheritagemichelle margulesPas encore d'évaluation

- Jovic 1992 Process Control Systems Principles of Design Operation and InterfacingDocument437 pagesJovic 1992 Process Control Systems Principles of Design Operation and InterfacingAlexandreCFilhoPas encore d'évaluation

- ASNT Publications CatalogDocument53 pagesASNT Publications CatalogJavier Dominguez100% (2)

- Christian Ethics: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument12 pagesChristian Ethics: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaNorthern ShinePas encore d'évaluation

- Jewish Standard, January 30, 2015, With SupplementsDocument92 pagesJewish Standard, January 30, 2015, With SupplementsNew Jersey Jewish StandardPas encore d'évaluation

- Crimson Rivers 1Document74 pagesCrimson Rivers 1julia.pachanaPas encore d'évaluation

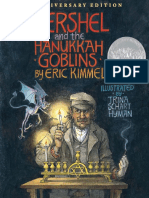

- 1990 Hershel and The Hanukkah GoblinsDocument34 pages1990 Hershel and The Hanukkah GoblinsHUI DAI100% (2)

- Self-Confidence: The Remarkable Truth of How A Small Change Can Boost Your Resilience and Increase Your Success. 10th Edition Paul McgeeDocument43 pagesSelf-Confidence: The Remarkable Truth of How A Small Change Can Boost Your Resilience and Increase Your Success. 10th Edition Paul Mcgeeclyde.harris924100% (3)

- Similes Metaphors Sound and Visual ImagesDocument22 pagesSimiles Metaphors Sound and Visual ImagesClaire TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Exam and Quiz Questions With Multimedia Responses PDFDocument2 pagesExam and Quiz Questions With Multimedia Responses PDFNelson KwamePas encore d'évaluation

- The Tribe of Ishmael PamphletDocument2 pagesThe Tribe of Ishmael PamphletMR.CFowlerELPas encore d'évaluation

- Rig Veda, Book Five, Hymns To Agni, by Vladimir YatsenkoDocument205 pagesRig Veda, Book Five, Hymns To Agni, by Vladimir YatsenkoVladimir Yatsenko100% (1)

- Angels and Angelology in The Middle AgesDocument271 pagesAngels and Angelology in The Middle Agesanon100% (5)

- (Autocritical Disability Studies) David Bolt - Metanarratives of Disability - Culture, Assumed Authority, and The Normative Social Order (2021, Routledge) - Libgen - LiDocument259 pages(Autocritical Disability Studies) David Bolt - Metanarratives of Disability - Culture, Assumed Authority, and The Normative Social Order (2021, Routledge) - Libgen - LiManu RodriguesPas encore d'évaluation

- BlazeVOX22 Spring22Document411 pagesBlazeVOX22 Spring22BlazeVOX [books]Pas encore d'évaluation