Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Document

Transféré par

retCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Document

Transféré par

retDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Original Paper

Med Princ Pract 2008;17:290295

DOI: 10.1159/000129608

Received: July 10, 2007

Revised: October 7, 2007

Psychiatric Disorders in Tsunami-Affected

Children in Ranong Province, Thailand

Nawanant Piyavhatkul a Srivieng Pairojkul b Chanyut Suphakunpinyo b

Departments of a Psychiatry and b Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand

Abstract

Objective: To study the prevalence of psychiatric disorders

in children affected by the Asian tsunami in Ranong province, Southern Thailand 10 months after the disaster. Subjects and Methods: The subjects were 47 boys and 47 girls,

age 118 years, who were affected by the tsunami. They

were participants in the Psychosocial Care and Protection

System for Tsunami-Affected Children in Ranong Province

project. The subjects were interviewed by a psychiatrist and

diagnoses were made according to DSM IV criteria. Results:

Of the 94 children, 47 (50%) had at least one psychiatric diagnosis: posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): n = 31 (33%);

major depression: n = 9 (9.6%); adjustment disorder: n = 9

(9.6%), and separation anxiety disorder: n = 3 (3.2%). The psychiatric diagnoses, specifically PTSD, were significantly associated with the childs age and exposure to the traumatic

events. Conclusion: Ten months after the tsunami disaster,

there is a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders in children, suggesting the importance of early identification, intervention and follow-up.

Copyright 2008 S. Karger AG, Basel

2008 S. Karger AG, Basel

10117571/08/01740290$24.50/0

Fax +41 61 306 12 34

E-Mail karger@karger.ch

www.karger.com

Accessible online at:

www.karger.com/mpp

Introduction

The Asian tsunami on the morning of December 26,

2004, as a result of an earthquake centered in the Indian

Ocean, measuring 9.09.3 on the Richter scale [1], devastated coastal areas of Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, Sri

Lanka, India and the Maldives. In Thailand, the area

along its Andaman Sea coastline of Krabi, Phang Nga,

Phuket, Ranong, Satun and Trang provinces were affected: 5,395 people died, 8,457 were injured and 2,817 were

missing [2], and 1,215 Thai children became orphans [3].

The tsunami destroyed 4,806 houses, 315 hotels and resorts, 4,365 fishing boats, 5,977 fish traps, and thousands

of acres of agricultural land, beach and coral reefs [24].

The disaster has had a major impact on the fishing and

coastal communities as well as the tourism industry.

Children experienced physical trauma from exposure

to the wave and psychological trauma from being in the

disaster. In addition they experienced the loss of significant persons, home, familiar community, school, teachers, property and lifestyle. The effect on livelihoods of

parents, resulting in economic and occupational disruption, also had an impact on the children. The Mental

Health Center for Thai Tsunami Disaster reported regressive symptoms in children, including enuresis, fear of

stranger, sleeping and eating problems, school and night

phobia, attention seeking, poor concentration, social isolation, poor school performance, depression, separation

Associate Prof. Nawanant Piyavhatkul

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine

Khon Kaen University

Khon Kaen 40002 (Thailand)

Tel./Fax +66 43 348 384, E-Mail nawanant@kku.ac.th

Downloaded by:

139.195.64.201 - 7/2/2014 4:26:17 PM

Key Words

Psychiatric disorders Disaster Tsunami Posttraumatic

stress disorder Children

Background of the Study

In Ranong province, 156 Thai died, 215 were injured,

9 were missing, and 103 children lost their parents [3].

Three districts, 47 villages, 1,509 households and 5,942

individuals were affected by the tsunami. Two local health

centers were severely damaged and one school was totally destroyed [3]. One dyke, 27 piers, 10 bridges and 21

streets were destroyed [4]. The majority of the affected

people were Muslim.

Most of the affected children in Ranong had a disadvantaged background before the disaster. Many were

from the lower socioeconomic class, had poor housing or

grew up in a dysfunctional family with domestic violence, stepfamilies and single-parent homes with poor

child protection. These children were prone to chronic

developmental trauma associated with trauma spectrum

Post-Tsunami Psychiatric Disorders in

Children

disorders and other emotional and behavioral disturbance [16]. Trauma exposure affects what children anticipate and focus on and how they organize the way they

appraise and process information. Trauma-induced alterations in threat perception are expressed in how they

think, feel, behave, and regulate their biologic systems

[17]. And, trauma early in the life cycle has long-term effects on the neurochemical response to stress [18]. Therefore, some of the children may have already been vulnerable to psychological problems, which affected the incidence of psychiatric illnesses, when the natural disaster

occurred.

Longitudinal studies on the long-term effect of natural

disaster on children found that symptoms decreased with

time, but continue to have effects on the children. Shaw

et al. [19] evaluated the 21-month follow-up in schoolchildren exposed to Hurricane Andrew. There were a continuing high level of posttraumatic stress symptoms and

evidence of increasing emotional and behavioral problems. The result of the study of Karakaya et al. [20] on

secondary school students 3.5 years after the Marmara

earthquake showed that 22.2% of them had probable

PTSD and 30.8% had probable depression diagnoses.

Their anxiety levels were also higher than in the normal

population. Green et al. [21] did a 17-year follow-up of

child survivors of the Buffalo Creek dam collapse. The

rate of PTSD at the time of follow-up was 7% compared

to a postflood rate of 32%. This suggests that children

seem to continue to suffer from psychiatric disorders and

psychopathologies for many years after the disaster and

therefore, it is important to screen tsunami-affected children for the treatment and follow-up continuously. A

screening instrument is also needed to identify the severely affected population as the target group for intervention.

The objective of this research was to study the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in children affected by the

tsunami and investigate the association of the psychiatric

morbidity and the nature of the traumatic experience in

the 10 months following the tsunami.

Subjects and Methods

Two hundred and six children who lived in difficult situations

such as poverty, parental death or divorce after the tsunami were

enrolled in this project. However, only 94 who were directly affected by the tsunami were assessed; 89 were not directly affected

and the parents of the remaining 23 did not allow them to participate in the study. The 94 children were 47 boys and 47 girls,

ages 118 years. They were participants in the Psychosocial Care

Med Princ Pract 2008;17:290295

291

Downloaded by:

139.195.64.201 - 7/2/2014 4:26:17 PM

anxiety and somatic symptoms in 148 children up to 18

years old who were evaluated a few weeks after the disaster [5].

Exposure to the trauma, age, gender, social support,

difficulties at home and loss of significant others are variables that have been reported to be associated with psychiatric disorders or psychiatric symptoms in the children who have experienced natural disasters [613].

There are data available about psychiatric disorders in

children affected by the tsunami. For example, Neuner et

al. [14] studied 264 Sri Lankan children who lived in

coastal communities in severely affected areas and found

the prevalence rate of tsunami-related posttraumatic

stress disorder (PTSD) ranged between 14 and 39%. Five

hundred and twenty-three juvenile survivors of the tsunami in Tamil Nadu were studied using instruments validated in Tamil Nadu and found that the prevalence of

acute PTSD was as high as 70.7% and that there was delayed-onset PTSD in 10.9% [7]. Thienkrua et al. [15] studied children affected by the tsunami in Phang Nga,

Phuket, and Krabi provinces, Thailand, using a modified

version of the PsySTART Rapid Triage System, the UCLA

PTSD Reaction Index, and the Birleson Depression SelfRating Scale 2 months after tsunami. They found the

prevalence of PTSD symptoms were 13% among children

living in camps, 11% among children in affected villages

contrasted with 6% among children from unaffected villages. For depressive symptoms, the prevalence rates were

11, 5 and 8%, respectively. There was no epidemiological

data available on psychiatric disorders in tsunami-affected children in other areas of Thailand.

Results

There were 24 Buddhists and 70 Muslims. Most of

their parents were blue-collar workers and fishermen. At

the time of the evaluation, 57 (60.6%) children were living

with their parent(s) and the others were living with other

relatives. Sixty-five (69.1%) of them lost an important figure in their lives from the tsunami, 52 (55.3%) lost their

parent(s), and 31 (33.0%) lost other close relatives. Seventeen (18.1%) children lost the familys property. Sociodemographic data are shown in table 1. Sixty-five (69.1%)

children were exposed to the traumatic events caused by

the tsunami, 40 (42.6%) of them were directly exposed to

the tsunami and 42 (44.7%) were exposed to the traumatic events subsequent to the tsunami such as seeing dead

bodies or hearing about a horrible death of their loved

ones (table 2).

Psychiatric Disorders

Half of the children (n = 47) had at least one psychiatric diagnosis: PTSD: n = 31 (33%); major depressive episodes: n = 9 (9.6%); chronic adjustment disorder (unresolved grief): n = 9 (9.6%), and separation anxiety disorder: n = 3 (3.2%). One young girl had developmental

trauma. There were 4 (4.3%) children with mental retardation and 4 (4.3%) with attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder, 4 (4.3%) children had developmental disorders

unrelated to the tsunami. There were 8 (8.5%) children

with more than one diagnosis.

292

Med Princ Pract 2008;17:290295

Table 1. Sociodemographic data of the 94 children

Sociodemographic factors

Gender

Male

Female

Age, years

05

610

1115

1618

Religion

Buddhism

Islam

Educational status

Underage and kindergarten

Primary school

Secondary school

Parents occupation

Fisherman

Agricultural

Blue-collar worker

Merchant

Government service

Unemployed

Living status

With parent(s)

Other relative

Family background

Death of parent(s) from other causes

Parental divorce

47

47

50.0

50.0

18

36

37

3

19.1

38.3

39.4

3.2

24

70

25.5

74.5

26

44

24

27.4

46.8

25.5

34

5

34

18

2

1

36.2

5.3

36.2

19.1

2.1

1.1

57

37

60.6

39.4

19

31

20.2

33.0

Younger children had a higher prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses than the older children. The highest prevalence of PTSD and unresolved grief was among those 6

10 years of age. Boys had a higher prevalence of depression but lower unresolved grief than girls. There was a

higher prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the children

who were exposed to the event and the group that lost

a significant figure in their lives. Forty of 65 children

(61.5%) who were exposed to the traumatic events caused

by the tsunami had some psychiatric diagnosis. The children who were directly exposed to the tsunami had a

higher prevalence of PTSD but lower prevalence of depression and unresolved grief than the group that was

exposed to the traumatic events subsequent to the tsunami (seeing dead bodies or hearing about the horrible

death of their loved ones, table 2).

Factors Associated with Psychiatric Disorders

There was no association between psychiatric disorders and religion, parents occupation, parental divorce,

Piyavhatkul /Pairojkul /Suphakunpinyo

Downloaded by:

139.195.64.201 - 7/2/2014 4:26:17 PM

and Protection System for Tsunami-Affected Children in Ranong

Province project funded by Enfant Development, in the areas of

Kaper district and Sooksamran subdistrict. The information

leading to the inclusion of these children in the program was derived from information provided by the school and local citizens.

The study authors received permission from caretakers for the

children to participate in the research in October 2005, 10 months

after the tsunami.

Demographic data on age, gender, religion, parents occupations and education, current caretaker data and the nature of the

trauma from the tsunami were collected by research assistants at

the same time the assessment was being carried out by a psychiatrist doing the semistructured psychiatric interview protocol as

part of a broader psychosocial evaluation of the children in the

project. With younger children, the accompanied caretakers were

also interviewed. If a child had any psychiatric symptoms, additional probes were asked to determine a diagnosis. A checklist for

PTSD criteria and diagnoses was used to determine if a child met

DSM IV criteria. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics, univariate analysis and bivariate logistic regression analysis

with a SPSS 11.5 program.

Table 2. Trauma, demographic data and psychiatric disorders

Gender

Male

Female

Age, years

05

610

1118

Trauma

Any loss

Loss of parent(s)

Loss of close relative(s)

Any exposure

Exposure to tsunami

Exposed to traumatic

events related to tsunami

Children

Any diagnosis

PTSD

Depression

SAD

47

47

50.0

50.0

24

23

51.1

48.9

18

36

40

19.1

38.3

42.6

10

25

12

65

52

31

65

40

69.1

55.3

33.0

69.1

42.6

42

44.7

Unresolved grief

15

16

31.9

34.0

7

2

14.9

4.3

0

3

0

6.4

3

6

6.4

12.8

55.6

69.4

30.0

3

18

10

16.7

50.0

25.0

3

2

4

16.7

5.6

10.0

1

1

1

5.6

2.8

2.5

2

6

1

11.1

16.7

2.5

37

29

18

40

24

56.9

55.8

56.3

61.5

60.0

22

14

11

31

21

33.8

26.9

34.4

47.7

52.5

8

7

4

7

3

12.3

13.5

12.5

10.8

7.5

3

2

1

2

1

4.6

3.8

3.1

3.1

2.5

9

9

4

6

1

13.8

17.3

12.5

9.2

2.5

26

61.9

18

42.9

11.9

2.4

16.7

SAD = Separation anxiety disorder.

Table 3. The positive results of binary backward stepwise logistic regression

Diagnosis

p value

Odds ratio

95% confidence interval

lower

upper

Any diagnosis

age 610 years

exposed to tsunami

exposed to event related to tsunami

0.000

0.012

0.031

7.631

3.961

2.929

2.483

1.361

1.103

23.452

11.525

7.781

PTSD

age 610 years

exposed to tsunami

exposed to event related to tsunami

0.017

0.000

0.019

3.894

7.635

3.655

1.279

2.514

1.240

11.854

23.194

10.770

Grief

age 610 years

exposed to event related to tsunami

0.015

0.042

24.987

7.810

1.879

1.078

332.368

56.577

Post-Tsunami Psychiatric Disorders in

Children

Discussion

In this study, psychiatric morbidity, especially PTSD,

was significantly associated with the childs age and exposure to the traumatic event, supportive of previous

findings [6, 11, 13, 1518]. Gender was not significantly

associated with PTSD, similar to the finding of McDermott et al. [10], which contrasted with the findings of

John et al. [6], Pynoos et al. [7] and Roussos et al. [9].

Our finding of a high prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in this sample fits with the concept of complex

trauma in children [22]. Our sample was from the popuMed Princ Pract 2008;17:290295

293

Downloaded by:

139.195.64.201 - 7/2/2014 4:26:17 PM

parental death from other causes, and the current caretaker when analyzed by univariate analysis. The results

of binary logistic stepwise backward regression analysis

showed that the psychiatric diagnosis and PTSD were significantly associated with the childs age and exposure to

the traumatic event caused by the tsunami (direct exposure to the tsunami or traumatic events related to tsunami). Major depressive episodes, separation anxiety disorder and comorbidity were not significantly associated

with any variables. Chronic adjustment disorder (unresolved grief reaction) was evidenced in the 6- to 10-year

age group who were exposed to the event (table 3).

294

Med Princ Pract 2008;17:290295

assessment or, most significant for this study, the time of

assessment after the disaster.

Our study demonstrates that chronic adjustment disorder (unresolved grief) was seen in children aged 610

years and was associated with exposure to dead bodies of

their loved ones or associated with hearing about horrible

deaths of their loved ones. There are no other studies that

mention this diagnosis and this association. Major depressive episodes, separation anxiety disorders and comorbidity were not significantly associated with any

variables.

We plan to follow up our sample for another 2.5 years

to see the long-term effect of tsunami on our children.

Limitation

A limitation of the study was the fact that the subjects

were selected from the Psychosocial Care and Protection

System for Tsunami-Affected Children in Ranong Province. Children were included who lost their parents in the

tsunami or were affected by the tsunami in other ways,

who were previously living in difficult situations, such as

divorce, death of the parents, or living with relatives.

Thus, they may not represent the general population of

the children who experienced the disaster.

Conclusion

Ten months after the Asian tsunami, there was a high

percentage of psychiatric disorders in tsunami-affected

children. The overall psychiatric morbidity and PTSD

were significantly associated with the childs age and exposure to the traumatic event. These results suggest the

importance of screening, follow-up and intervention for

these children.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Enfant Development for funding support for the Psychosocial Care and Protection System for Tsunami-Affected Children in Ranong Province project during

20052006.

Piyavhatkul /Pairojkul /Suphakunpinyo

Downloaded by:

139.195.64.201 - 7/2/2014 4:26:17 PM

lation who had a disadvantaged background prior to the

disaster, and who might have been exposed to repeated

trauma, which has been found to impact on the childs

affect regulation, attachment, behavioral regulation, integration of information and experience, cognition, selfconcept and regulation of the biologic systems [12]. Furthermore, kindling phenomena might occur when people

are repeatedly traumatized, which may lead to lasting

neurobiological and behavioral (characterological)

changes mediated by alterations in the temporal lobe [11].

Therefore, exposure to the developmental trauma before

the disaster might make some children more susceptible

to traumatization by the tsunami and the suffering of

loss.

Other researchers have studied the psychological impact of children affected by the tsunami and also found

a high prevalence of PTSD [6, 14]. On the other hand,

research on Thai children who lived in Phang Nga, Phuket, and Krabi provinces showed lower prevalence of

PTSD symptoms (613%) in tsunami-affected children

2 months after the tsunami [15] compared to 33% of

PTSD in our sample. They found the prevalence of depressive symptoms to be 511%, which is lower than the

prevalence in our study. Furthermore, when we combined major depressive disorder and chronic adjustment

disorder (unresolved grief), the prevalence of children

with significant depressive symptoms reached 19.2%.

The difference might be explained by the screening instruments that were utilized, since the cutoff points in

the Thai version [15] had not been validated for sensitivity and specificity in Thai children, and this study utilized a clinical diagnostic interview performed by a native Thai psychiatrist. There may also have been differences in the demographics of the study samples. For

example, there are more Muslim children and more

children with lower socioeconomic status and difficult

backgrounds in the affected communities in our study

that could have caused vulnerability as discussed

above.

As compared with other types of natural disaster, our

researchers found a high prevalence of PTSD and a moderate prevalence of depression in children. Other studies

reported PTSD in the range of 4.595% and a 776%

prevalence of depression in children exposed to earthquakes, super-cyclone and wildfire disasters. Separation

anxiety disorder and conversion disorder were also reported to be found in these children [20, 23, 24]. The different rates observed in our study as contrasted with other studies may be explained by differences in culture, severity of the trauma, nature of the disaster, method of

References

Post-Tsunami Psychiatric Disorders in

Children

8 Goenjian AK, Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Najarian LM, Asarnow JR, Karayan I, Ghurabi

M, Fairbanks LA: Psychiatric comorbidity in

children after the 1988 earthquake in Armenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry

1995;34:11741184.

9 Roussos A, Goenjian AK, Steinberg AM,

Sotiropoulou C, Kakaki M, Kabakos C,

Karagianni S, Manouras V: Posttraumatic

stress and depressive reactions among children and adolescents after the 1999 earthquake in Ano Liosia, Greece. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:530537.

10 McDermott BM, Lee EM, Judd M, Gibbon P:

Posttraumatic stress disorder and general

psychopathology in children and adolescents following a wildfire disaster. Can J Psychiatry 2005;50:137143.

11 Kolaitis G, Kotsopoulos J, Tsiantis J, Haritaki S, Rigizou F, Zacharaki L, Riga E, Augoustatou A, Bimbou A, Kanari N, Liakopoulou M, Katerelos P: Posttraumatic stress

reactions among children following the Athens earthquake of September 1999. Eur Child

Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 12:273280.

12 Vijayakumar L, Kannan GK, Daniel SJ: Mental health status in children exposed to tsunami. Int Rev Psychiatry 2006;18:507513.

13 La Greca A, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM,

Prinstein MJ: Symptoms of posttraumatic

stress in children after Hurricane Andrew: a

prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol

1996;64:712723.

14 Neuner F, Schauer E, Catani C, Ruf M, Elbert

T: Post-tsunami stress: a study of posttraumatic stress disorder in children living in

three severely affected regions in Sri Lanka.

J Trauma Stress 2006;19:339347.

15 Thienkrua W, Cardozo BL, Chakkaraband

ML, Guadamuz TE, Pengjuntr W, Tantipiwatanaskul P, Sakornsatian S, Ekassawin S,

Panyayong B, Varangrat A, Tappero JW,

Schreiber M, van Griensven F: Symptoms of

post traumatic stress disorder and depression among children in tsunami-affected areas in southern Thailand. JAMA 2006; 296:

576578.

16 van der Kolk BA: The body keeps the score:

memory and the evolving psychobiology of

posttraumatic stress. Harv Rev Psychiatry

1994;1:253265.

17 van der Kolk BA: The neurobiology of childhood trauma and abuse. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2003;12:293317.

18 van der Kolk BA, Saporta J: The biological

mechanisms and treatment of intrusion and

numbing. Anxiety Res 1991;4:199212.

19 Shaw JA, Applegate B, Schorr C: Twentyone-month follow-up study of school-age

children exposed to Hurricane Andrew. J

Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;35:

359364.

20 Karakaya I, Agaoglu B, Coskun A, Sismanlar

SG, Yildiz Oc O: The symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety in adolescent students

three and a half years after the Marmara

earthquake. Turk Psikiyatri Derg 2004; 15:

257263.

21 Green BL, Grace MC, Vary MG, Kramer TL,

Gleser GC, Leonard AC: Children of disaster

in the second decade: a 17-year follow-up of

Buffalo Creek survivors. J Am Acad Child

Adolesc Psychiatry 1994;33:7179.

22 Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C,

Blaustein M, Cloitre M, DeRosa R, Hubbard

R, Kagan R, Mallah K, Olafson E, van der

Kolk BA: Complex trauma in children and

adolescents. Psychiatr Ann 2005;35:390

398.

23 Grigorian HM: The Armenian earthquake;

in Linda SA (ed): Responding to Disaster.

Washington, American Psychiatric Press,

1992, pp 157167.

24 Kar N, Mohapatra PK, Nayak KC, Pattanaik

P, Swain SP, Kar HC: Post-traumatic stress

disorder in children and adolescents one

year after a super-cyclone in Orissa, India:

exploring cross-cultural validity and vulnerability factors. BMC Psychiatry 2007;7:8.

Med Princ Pract 2008;17:290295

295

Downloaded by:

139.195.64.201 - 7/2/2014 4:26:17 PM

1 Wikipedia contributors: 2004 Indian Ocean

earthquake [homepage on the Internet].

Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia [updated

2006 May 22; cited 2006 May 23]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.

php?title=2004_Indian_Ocean_earthquake

&oldid=54573150.

2 Tsunami Memorial Project [homepage on

the Internet]. Ministry of Natural Resources

and Environment Thailand: Information on

the disaster [updated 2006 May 17; cited

2006 May 23]; Available from: http://www.

tsunamimemorial.or.th/information.htm

3 Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, Ministry of the interior of Thailand:

2006 Disaster report [homepage on the Internet]. Ministry of the interior of Thailand

[updated 18 May 2006; cited 2006 May 22].

Available from: www.disaster.go.th/disaster01/page/report_2547_2548/p210228.

4 Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, Ministry of the interior of Thailand:

Earthquake/Tsunami Victims Relief Effort

[homepage on the Internet]. Ministry of the

interior of Thailand [updated 18 May

2006;cited 2006 May 22]. Available from:

http://www.disaster.go.th/html/english/

general/ddpm_tsunami.pdf

5 The Mental Health Center (MHC) for Thai

Tsunami Disaster: Symptoms Report of

Mental Health Services for Tsunami Victims

[homepage on the Internet]. Department of

Mental Health, Ministry of Public Health of

Thailand. c2005 [cited 2005 Feb 2]. Available

from: http://www.mis12.moe.go.th/tsunami/index.asp

6 John PB, Russell S, Russell PS: The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among

children and adolescents affected by tsunami disaster in Tamil Nadu. Disaster Manag

Response 2007;5:37.

7 Pynoos RS, Goenjian A, Tashjian M, Karakashian M, Manjikian R, Manoukian G,

Steinberg AM, Fairbanks LA: Post-traumatic stress reactions in children after the 1988

Armenian earthquake. Br J Psychiatry 1993;

163:239247.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Jadwal Jaga IGD 1Document25 pagesJadwal Jaga IGD 1retPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Itinerary BALIDocument7 pagesItinerary BALIretPas encore d'évaluation

- Daftar Kelulusan Osce November 2018 PDFDocument73 pagesDaftar Kelulusan Osce November 2018 PDFAisyah Althafunnisa Bayu PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- EaasmcDocument27 pagesEaasmcretPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Ante Natal CareDocument82 pagesAnte Natal CareretPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Group Moderators' Manual BookDocument37 pagesGroup Moderators' Manual BookretPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- New Text DocumentDocument1 pageNew Text DocumentretPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Soy Milk Consumption and Blood Pressure Among Type 2 Diabetic Patients With NephropathyDocument7 pagesSoy Milk Consumption and Blood Pressure Among Type 2 Diabetic Patients With NephropathyretPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- A B C D E: Senin Selasa Rabu Kamis Jumat SabtuDocument11 pagesA B C D E: Senin Selasa Rabu Kamis Jumat SabturetPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- New Text DocumentDocument1 pageNew Text DocumentretPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grafik GDS Ny. I: Tanggal PemeriksaanDocument7 pagesGrafik GDS Ny. I: Tanggal PemeriksaanretPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- 4-Planning Tools & TechniquesDocument17 pages4-Planning Tools & TechniquesretPas encore d'évaluation

- Bali Corat CoretDocument1 pageBali Corat CoretretPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Meeting 3Document28 pagesMeeting 3retPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Countries' Etiquette ARGENTINADocument3 pagesCountries' Etiquette ARGENTINAretPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Optimiz Ing The Membe R'S: Pation in SDC (Art Div Ision)Document7 pagesOptimiz Ing The Membe R'S: Pation in SDC (Art Div Ision)retPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Etipro Kelompok 4 (Kelas G)Document12 pagesEtipro Kelompok 4 (Kelas G)retPas encore d'évaluation

- Cleaning AgentSuppliesDocument5 pagesCleaning AgentSuppliesretPas encore d'évaluation

- Equipment HKDocument43 pagesEquipment HKretPas encore d'évaluation

- Organization ChartDocument29 pagesOrganization Chartret100% (1)

- Countries' Etiquette AFGHANISTANDocument4 pagesCountries' Etiquette AFGHANISTANretPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- 1-Introduction To Management & OrganizationDocument22 pages1-Introduction To Management & OrganizationretPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Strategic ManagementDocument13 pages3 Strategic ManagementretPas encore d'évaluation

- FlooringDocument20 pagesFlooringretPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Tata Boga (India)Document5 pagesTata Boga (India)retPas encore d'évaluation

- 5-Organization Structure & DesignDocument19 pages5-Organization Structure & DesignretPas encore d'évaluation

- 9-Foundations of ControlDocument13 pages9-Foundations of ControlretPas encore d'évaluation

- 447Document10 pages447retPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- 5-Organization Structure & DesignDocument19 pages5-Organization Structure & DesignretPas encore d'évaluation

- Meeting 3Document33 pagesMeeting 3retPas encore d'évaluation

- Trail Mix Cookies IKDocument24 pagesTrail Mix Cookies IKDwi Intan WPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Health Issues - ADHD Among ChildrenDocument9 pagesMental Health Issues - ADHD Among ChildrenFelixPas encore d'évaluation

- Notice: Agency Information Collection Activities Proposals, Submissions, and ApprovalsDocument2 pagesNotice: Agency Information Collection Activities Proposals, Submissions, and ApprovalsJustia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- N4H InvitationLetter - FinalDocument2 pagesN4H InvitationLetter - Finalluis DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- 2018 MUSE Inspire Conference - Show and Tell SessionsDocument13 pages2018 MUSE Inspire Conference - Show and Tell SessionsMichele LambertPas encore d'évaluation

- Drug Study 1Document2 pagesDrug Study 1Hafza MacabatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Disaster Preparedness IntroDocument10 pagesDisaster Preparedness IntroBernadette-Mkandawire MandolomaPas encore d'évaluation

- Typology of Nursing Problems in Family Nursing PracticeDocument4 pagesTypology of Nursing Problems in Family Nursing PracticeLeah Abdul KabibPas encore d'évaluation

- NCLEX RN Practice Questions Set 1Document6 pagesNCLEX RN Practice Questions Set 1Jack SheperdPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Assoc Between Poor Sleep Quality - Depression Symptoms Among ElderlyDocument8 pagesAssoc Between Poor Sleep Quality - Depression Symptoms Among ElderlyWindyanissa RecitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab Report 15438869 20231127064225Document1 pageLab Report 15438869 20231127064225carilloabhe21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tea and Industrial RevolutionDocument4 pagesTea and Industrial RevolutionPhuong NguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing - Burn InjuryDocument39 pagesNursing - Burn Injuryamaracha2003Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mini Clinical Examination (Mini-CEX)Document21 pagesMini Clinical Examination (Mini-CEX)Jeffrey Dyer100% (1)

- PNA 2012 National Convention LectureDocument60 pagesPNA 2012 National Convention LectureHarby Ongbay AbellanosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Peran Perawat KomDocument27 pagesPeran Perawat Komwahyu febriantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Declaration FormDocument1 pageHealth Declaration FormUzair KhalidPas encore d'évaluation

- Adani Targets Debt Cuts, Income Boost Coastal Shipping To Get Infra Status, Says SonowalDocument20 pagesAdani Targets Debt Cuts, Income Boost Coastal Shipping To Get Infra Status, Says SonowalboxorPas encore d'évaluation

- Disaster Nursing SAS Session 14Document6 pagesDisaster Nursing SAS Session 14Niceniadas CaraballePas encore d'évaluation

- Letters of Intent (Cover Letters)Document6 pagesLetters of Intent (Cover Letters)anca_ramona_s0% (1)

- Care ReportDocument23 pagesCare ReportSindi Muthiah UtamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Pattern Before Hospitalization During HospitalizationDocument2 pagesPattern Before Hospitalization During HospitalizationJean WinPas encore d'évaluation

- Gear Oil 85W-140: Safety Data SheetDocument7 pagesGear Oil 85W-140: Safety Data SheetsaadPas encore d'évaluation

- Fatal Airway Obstruction Due To Ludwig'sDocument6 pagesFatal Airway Obstruction Due To Ludwig'sRegina MugopalPas encore d'évaluation

- Physiological Changes Postpartum PeriodDocument2 pagesPhysiological Changes Postpartum PeriodEurielle MiolePas encore d'évaluation

- Nejmra 2023911Document8 pagesNejmra 2023911Merry LeePas encore d'évaluation

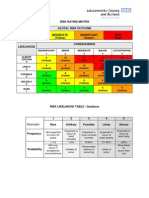

- Example of A NHS Risk Rating MatrixDocument2 pagesExample of A NHS Risk Rating MatrixRochady SetiantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Test Bank For Occupational Therapy in Mental Health A Vision For Participation 2nd Edition Catana Brown Virginia C Stoffel Jaime MunozDocument3 pagesTest Bank For Occupational Therapy in Mental Health A Vision For Participation 2nd Edition Catana Brown Virginia C Stoffel Jaime MunozDavid Ortiz97% (36)

- ResumeDocument4 pagesResumeAaRomalyn F. ValeraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Influence of Music in Horror Games (Final Draft)Document7 pagesThe Influence of Music in Horror Games (Final Draft)Panther LenoXPas encore d'évaluation