Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Architecture

Transféré par

Rinny Rebécca0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

19 vues5 pagesARCHITECTURE

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentARCHITECTURE

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

19 vues5 pagesArchitecture

Transféré par

Rinny RebéccaARCHITECTURE

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 5

CHAPTER 2

THE PROTO-HISTORIC PERIOD: THE INDUS

VALLEY CIVILIZATION

Before 1924 the history of Indian art in surviving monuments could not

be traced farther back than the Macedonian invasion in the fourth century

B.C. The entire concept of the early cultures of India was changed by the

dramatic discovery of a great urban civilization that existed

contemporaneously with the ancient culture of Mesopotamia in the tliird

millennium B.c.^ Although the chief centres ofthis civihzation were

brought tohght in the Indus Valley, there are indications that it extended

uniformly as far north as the Punjab and the North-west Frontier

(Pakistan) and may have included all or part of Rajputana and the Ganges

Valley. The term Indo-Sumerian, sometimes used to describe this period

of Indian history, derives from the resemblance ofmany objects at the

cliiefcentres ofthis culture to Mesopotamian forms. It is, in a sense, a

misleading designation because it impUes that this Indian civihzation was

a provincial offshoot of Sumeria, whereas it is more proper to think of it

as an entirely separate culture that attained just as high a level as that of

the great Mesopotamian empires. A better title would be the 'Indus Valley

Period', since this designation is completely descriptive of the principal

centres of this civihzation. As will be seen, it is not so much the

relationships to Mesopotamia and Iran that are surprising, as the complete

separateness and autonomy of this first great civihzation in Indian history

in the major aspects of its development. Typical of the independence of

the Indus Valley art, and the mysteries surrounding it, is the undeciphered

script which appears on the many steatite seals or tahsmans found at all

the centres excavated.^ The Indus Valley Period certainly cannot be

described as prehistoric, nor does the evidence of the fmds entirely permit

the definition of chalcohthic in the sense of a bronze or copper age. In

view of the many well-forged links with later developments in Indian

culture, a better descriptive term would be 'proto-historic', wliich defines

its position in the period before the begiiming ofknown history and its

forecast oflater phases ofIndian civihzation.

The principal cities of the Indus Valley culture are Mohenjo-daro on the

Indus River and Harappa in the Punjab. The character of the finds has led

investigators to the conclusion that the peoples of the Indus culture must

have had some contact with ancient Mesopotamia. These commercial

comiexions with the ancient Near East were maintained by sea and

overland by way of Baluchistan. The dating of the Indus Valley

civilizationdepends almost entirely on comparison with vestiges of

similar architectural and sculptural remains in Mesopotamia and on the

discovery of objects of Indian origin in a

level corresponding to 2400 B.C. at Tel Asmar in Iraq. On the basis of

these finds and other related objects found at Kish and Susa in Iran, the

beginnings of the Indus culture.

have been fixed in the middle of the third millennium B.C. The latest

evidence suggests that the civilization of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa

lasted for about eight hundred years, until the seventeenth century b.c.^ It

was succeeded by an inferior and very obscure culture known as the

Jhukar, wliich endured up to the time of the Aryan invasion in about

1500 B.C.

Allowing about five hundred years for the development of this

civihzation, the great period of the Indus Valley culture occurred in the

later centuries of the third millennium

B.C., and may be described as an urban concentration or assimilation of

isolated and primitive village centres existing in Baluchistan and Sind as

early as 3500 or even 4000 B.C. The trade relations that linked these

settlements with early dynastic Sumer and the culture of Iran apparently

continued as late as the period of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa.

The Indus Valley culture was one of almost monotonous uniformity both

in space and time : there is nothing to differentiate fmds from Sind and

the North-west Frontier ; nor is there any perceptible variation in the style

of objects, such as seals, found in levels separated by hundreds of years,

although it is apparent that such forms of Sumerian art as were introduced

early in the history ofthe culture were gradually absorbed or replaced

by elements of a more truly Indian tradition.

The end of the Indus culture is as mysterious as its origin. Whether the

end came in a sudden cataclysm, or whether the culture underwent a long

period of disintegration and dechne, is impossible to say."* The most

hkely explanation for its disappearance is that the great cities had to be

abandoned because ofthe gradual desiccation of the region of Sind.

The descriptions by Arrian ofthe terrible deserts encountered by

Alexander in his march across Sind leave no doubt that the region had

been a desert for some time before the Macedonian invasion. Indeed,

even in Alexander's time the legend was current that fabled Semiramis

and Cyrus the Achaemenian had lost whole armies in the deserts of

Gedrosia. Later Greek writers described the region as filled with ' the

remains of over a thousand towns and villages once full of men'. It is

highly probable that the Aryan invasions from 1500 to 1200 B.C.

coincided with the end of this Dravidian civilization.'

Viewed from an aesthetic point of view, the ruins of the Indus Valley

cities are, as Percy Brown has remarked, 'as barren as would be the

remains of some present-day

working town in Lancashire'.^ Certainly there is notliing more boring to

the layman or less revealing than those archaeological photographs of

endless cellar holes that might as well be views ofPompeii or the centre

of present-day Berlin. Archaeologists have, however, been able to draw

certain conclusions on the basis of these architectural renmants

of the skeleton of the Indus culture that enable us partially to clothe that

frame in flesh.The architecture, as one would expect ofa commercial

urban civihzation, was ofa startling utUitarian character, with a uniform

sameness of plan and construction that alsotypifies the products of the

Indus culture in pottery. The buildings consisted of houses,

markets, storerooms, and offices ; many of these structures consisted of a

brick groundstorey with one or more additional floors in wood.

Everytliing about the construction

of the ancient city of Mohenjo-daro reflects a completely matter-of-fact,

business-like point of view, from the city plan as a whole to the almost

total lack of architectural ornamentation.

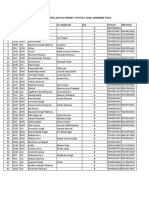

The excavations ofMohenjo-daro have revealed that the site v^as

systematically laid out on a regular plan in such a w^ay that the principal

streets ran north and south in order to take full advantage of the

prevailing winds (Figure i). This type of urban plan is in itself

a puzzling novelty, different from the rabbit-warren tradition ofcity

planning so universal in both ancient and modem times in India and

Mesopotamia. It must have been introduced when such plans were

already perfected in ancient Mesopotamia. The baked brick construction

is perhaps the feature most suggestive of the building methods of the

ancient cities of Mesopotamia, but the bricks of Mohenjo-daro and

Harappa are firebaked, and not sun-dried, like the fabric of Sumer and

Babylon. This teclinique ob-viously implies the existence of vast amounts

of timber to fire the kilns, and reminds us once again that the province of

Sind in these remote times was heavily forested, and not the arid desert

that we know to-day. Certain architectural features, such as the use of

narrow pointed niches as the only forms of interior decoration along the

Indus, are also found as exterior architectural accents at Khorsabad in

Mesopotamia, and are suggestive of a relationship with the ancient Near

East. Many examples of vaulting of a corbelled type have been

discovered, but the true arch was apparently unknown to the builders of

Mohenjo-daro. No buildings have been discovered at either Mohenjodaro or Harappa riiat can be identified as temples, although at both sites

there were great artificial mounds presumably serving as citadels. On the

liighest tumulus at Mohenjo-daro are the ruins of a Buddhist stupa that

may well have been raised on the remains of an earher sanctuary.

Among the more interesting structures at Mohenjo-daro were the remains

of a great public bath, and it is possible tliat this establishment, together

with the smaller baths attached to almost every private dwelling, may

have been intended for ritual ablutions such as are performed in the tanks

of the modern Hindu temple.

The regularity of the city plan of Mohcnjo-daro and the dimensions of the

individual houses are fir superior to the arrangements of later Indian

cities, as, for example, the Greek and Kushan cities at TaxOa in the

Punjab. Indeed, it could be said that the population of the Indus cities

Hved more comfortably than did their contemporaries in the

crowded and ill-built metropohses of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Even more

remarkable in comparison to secular arcliitecture in Mesopotamia is the

high development of rubbish- shoots and drains in private houses and

streets. This superiority to, and independence from, the Near East may

again be explained by the availabihty offuel for the manufacture

of terra-cotta in the Indus Valley. On the basis of the many imiovations

and conveniences in civic arcliitecture, as more than one authority has

stated, we are led to the conclusion that the centres of civihzation along

the Indus in the tliird millennium b.c. were vastly rich commercial cities

in which the surplus wealth was invested for the pubhe

good in the way of municipal improvement, and not assigned to the

erection of huge and expensive monuments dedicated to the royal cult.

Among the fragments of sculpture found at Mohenjo-daro is a male bust

carved of a whitish limestone originally inlaid with a red paste (Plate i).''

Most likely it was a votive portrait of a priest or shaman. There has been

a great deal of speculation on the identification of this and other bearded

heads found at Mohenjo-daro. Some scholars have argued that they

represent deities or portraits of priests. In the present example the

disposition of the robe over the left shoulder is not unlike the Buddhist

sahghat'i. The way in which the eyes are represented, as though

concentrated on the tip of the nose, is suggestive

of a well-known method of yoga meditation, and would therefore favour

the identification as a priest or holy man.

The similarities of these statues to Mesopotamian sculpture in the plastic

conception of the head in hard, mask-hke planes and certain other

teclinical details are fairly close, and yet not close enough to prove a real

relationsliip. The resemblance to Sumerian heads consists mainly in the

general rigidity and in such aspects as the wearing of the beard with

shaven upper lip, the method of representing the eyebrows in sahent

rehef, and the indication of the hair by lines incised on the surface of the

stone. These devices of essentially conceptual portraiture, however, are

too common a teclinique among all ancient peoples to permit us to draw

any conclusions. Details such as the trefoil design on

the costume, as well as the mode ofhairdressing, may be matched in

Sumerian sculpture. More suggestive of a real connexion between the

sculpture of the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia are a number of statuettes

reputed to have been excavated in the Indus

Valley. They are quite comparable to the log-like statues of Gudca and

other Mesopotamian statues of the tliird miUennium B.C. One of these

figurines has a cartouche inscribed in the Mohenjo-daro script.

Presumably these idols are provincial - that is, Indian

variants of Sumerian cult statues - and their presence in the Indus Valley

reveals that at least some relation, perhaps religious as well as styhstic,

existed between the civihzations of the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia.^

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Cadava of Veils and MourningDocument20 pagesCadava of Veils and MourningRinny RebéccaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Divine Rider On A Composite Elephant Preceded by A Demon: Let'S LookDocument4 pagesDivine Rider On A Composite Elephant Preceded by A Demon: Let'S LookRinny RebéccaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- His648:History of Indian Diaspora: Course OutcomesDocument1 pageHis648:History of Indian Diaspora: Course OutcomesRinny RebéccaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dholavira PDFDocument23 pagesDholavira PDFRinny RebéccaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Force Which Is Born of Truth and Love or NonviolenceDocument4 pagesThe Force Which Is Born of Truth and Love or NonviolenceRinny RebéccaPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- National Student Union of India: Rahul Prakash DukandeDocument3 pagesNational Student Union of India: Rahul Prakash Dukandejoshi_mandar749Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Ancient Tamil CivilizationDocument11 pagesAncient Tamil CivilizationUday DokrasPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- List of Persona 2 Spell ListDocument7 pagesList of Persona 2 Spell Listrafaela428Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Astrology Yoga For EducationDocument14 pagesAstrology Yoga For EducationTanishq SahuPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Trifurcation Penstock ModellingDocument9 pagesTrifurcation Penstock Modellingtsinghal_19Pas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- List of Candidates Selected For The Session 2012-2013Document11 pagesList of Candidates Selected For The Session 2012-2013Vinod JoshiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Avalokitesvara DharaniDocument8 pagesAvalokitesvara DharaniYaho HosPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Bharat Sarkar Ko Sandesh Aur Sindhi Samaj Ka SudharDocument3 pagesBharat Sarkar Ko Sandesh Aur Sindhi Samaj Ka SudharpavangoldPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- I Mostly Use Parashari and Jaimini Method of Timing EventsDocument3 pagesI Mostly Use Parashari and Jaimini Method of Timing Eventsvinayak bhalekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution of Hindu LawDocument18 pagesEvolution of Hindu LawDhavalPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- VakyanirmanamDocument72 pagesVakyanirmanamramishPas encore d'évaluation

- Filipino Gods and GoddessesDocument2 pagesFilipino Gods and GoddessesKiyomi LabradorPas encore d'évaluation

- Hotel Build India 2013 - Attendee ListDocument10 pagesHotel Build India 2013 - Attendee ListJanaki Rama Manikanta NunnaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Institute Name: National Law University, Jodhpur (IR-L-U-0414)Document5 pagesInstitute Name: National Law University, Jodhpur (IR-L-U-0414)Jinu JosePas encore d'évaluation

- Sikkim Tour PlanDocument4 pagesSikkim Tour Planfireballhunter646Pas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Loan Application Updates Aavya Homes - 4Th Oct 2018, Workinf FilesDocument4 pagesLoan Application Updates Aavya Homes - 4Th Oct 2018, Workinf Fileskrishan chaturvediPas encore d'évaluation

- Raga Pravagam English FullDocument312 pagesRaga Pravagam English Fullmithili71% (7)

- Catalog 2019 PDFDocument237 pagesCatalog 2019 PDFDinesh RupaniPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Judge Vimshotri DahsaDocument7 pagesHow To Judge Vimshotri DahsaNirmal Kumar Bhardwaj100% (22)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Lucknow JNVST 2017Document404 pagesLucknow JNVST 2017Kaushal Sagar100% (1)

- Subhan Rao v. Parvathi BaiDocument12 pagesSubhan Rao v. Parvathi BaideekshatripathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Telephone Udaipur Important PersonsDocument12 pagesTelephone Udaipur Important Personsjohnyramnani50% (2)

- The Cultural Survivals of Kurru People Gleaned From The Ritual Re Enactment of " Kuravar Padukalam'Document6 pagesThe Cultural Survivals of Kurru People Gleaned From The Ritual Re Enactment of " Kuravar Padukalam'Editor IJTSRDPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- MUMBAI Notes PDFDocument72 pagesMUMBAI Notes PDFSudhama100% (1)

- Nishanta PDFDocument48 pagesNishanta PDFRahul GhoshPas encore d'évaluation

- JEET ResumeDocument3 pagesJEET ResumeAkash ModiPas encore d'évaluation

- Education DepartmentDocument4 pagesEducation DepartmentDakshu SindhuPas encore d'évaluation

- No Nama Siswa Agama PKN B Indo MTK IPA IPS SBDP Pjok B Jawa B InggrisDocument2 pagesNo Nama Siswa Agama PKN B Indo MTK IPA IPS SBDP Pjok B Jawa B InggrisSD HARAPAN SURABAYAPas encore d'évaluation

- Audit PC JainDocument20 pagesAudit PC JainadityaduaPas encore d'évaluation

- Comprehensive Philosophy of Gurbani - Amritpal Singh UKDocument6 pagesComprehensive Philosophy of Gurbani - Amritpal Singh UKGiani Amritpal SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)