Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Gradualism

Transféré par

Anshuman PandeyCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gradualism

Transféré par

Anshuman PandeyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Assignment:

Critical Reasoning and Systems Thinking

Anshuman Pandey, Priya Yadav, Vivek Sundar, Yashkiranjeet Singh

Has Gradualism in Indias economic policy worked?

India was a latecomer to economic reforms (claim), embarking on the process in earnest only in

1991, in the wake of an exceptionally severe balance of payments crisis (data). The need for a

policy shift had become evident much earlier (claim), as many countries in East Asia achieved

high growth and poverty reduction through policies that emphasized greater export orientation and

encouragement of the private sector (data). India took some steps in this direction in the 1980s,

but it was not until 1991 that the government signaled a systemic shift to a more open economy

with greater reliance upon market forces, a larger role for the private sector including foreign

investment, and a restructuring of the role of government (data).

Indias economic performance in the post-reform period has many positive features (claim). The

average growth rate in the ten-year period from 19921993 to 20012002 was around 6.0 percent,

as shown in Table 1, which puts India among the fastest growing developing countries in the 1990s

(data). This growth record is only slightly better than the annual average of 5.7 percent in the

1980s (data), but it can be argued that the 1980s growth was unsustainable (claim), fuelled by a

buildup of external debt that culminated in the crisis of 1991 (evidence). In sharp contrast, growth

in the 1990s was accompanied by remarkable external stability despite the East Asian crisis

(claim). Poverty also declined significantly in the post-reform period and at a faster rate than in

the 1980s, according to some studies (as Ravallion and Datt discuss in this issue) (data). However,

the ten-year average growth performance hides the fact that while the economy grew at an

impressive 6.7 percent in the first five years after the reforms, it slowed down to 5.4 percent in the

next five years (data). India remained among the fastest growing developing countries in the

second sub-period because other developing countries also slowed down after the East Asian crisis,

but the annual growth of 5.4% was much below the target of 7.5%, which the government had set

for the period (data). Inevitably, this has led to some questioning about the effectiveness of the

reforms (claim).

Opinions on the causes of Indias growth deceleration vary (Assumption). World economic growth

was slower in the second half of the 1990s (data), and that would have had some dampening effect

(claim), but Indias dependence on the world economy is not large enough for this to account for

the slowdown (Moderate Argument). Critics of liberalization have blamed the slow down on the

effect of trade policy reforms on domestic industry (for ex- Nambiar, Mungekar and Tadas, 1999;

Chaudhuri, 2002) (external evidence). However, the opposite view is that the slowdown is due not

to the effects of reforms, but rather to failure to implement the reforms effectively (counter

evidence). Thus, in turn is often attributed to Indias gradualist approach to reform, which has

meant a frustratingly slow pace of implementation (evidence). However, even a gradualist pace

should be able to achieve significant policy changes over ten years (claim). This paper examines

Indias experience with gradualist reforms from this perspective (claim).

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Top 10 Cyber Security Challenges For BusinessesDocument3 pagesThe Top 10 Cyber Security Challenges For BusinessesAnshuman Pandey100% (1)

- GTÇTÇ Eéç Xåväâá - Äx: Bharat Petroleum Corporation LTDDocument12 pagesGTÇTÇ Eéç Xåväâá - Äx: Bharat Petroleum Corporation LTDAnshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Whistle-Blowing/ Vigil Mechanism Under Companies Act, 2013Document6 pagesWhistle-Blowing/ Vigil Mechanism Under Companies Act, 2013Anshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

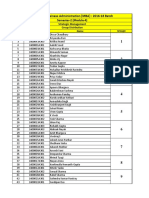

- Strategic Management (Group Distribution)Document1 pageStrategic Management (Group Distribution)Anshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Final ReportDocument12 pagesFinal ReportAnshuman Pandey100% (1)

- Social Media Marketing in The Film IndustryDocument19 pagesSocial Media Marketing in The Film IndustryAnshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- StarbucksDocument28 pagesStarbucksAnshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bausch Lomb Case StudyDocument5 pagesBausch Lomb Case StudyAnshuman Pandey100% (1)

- Short Speech OnDocument10 pagesShort Speech OnAnshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Hrishikesh: by Anshuman PandeyDocument16 pagesHrishikesh: by Anshuman PandeyAnshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Finance AssignmentDocument10 pagesFinance AssignmentAnshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- BNL StoreDocument19 pagesBNL StoreAnshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Case About Remedial Training: Praveen B Rahul Rohilla Puneeth NishanthDocument8 pagesThe Case About Remedial Training: Praveen B Rahul Rohilla Puneeth NishanthAnshuman PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Uncle SamDocument3 pagesUncle SamJonnyPas encore d'évaluation

- Article On Joseph RoyeppenDocument4 pagesArticle On Joseph RoyeppenEnuga S. ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Terrorism in NigeriaDocument40 pagesTerrorism in NigeriaAkinuli Olaleye100% (5)

- Letter To Swedish Ambassador May 2013Document2 pagesLetter To Swedish Ambassador May 2013Sarah HermitagePas encore d'évaluation

- Full Drivers License Research CaliforniaDocument6 pagesFull Drivers License Research CaliforniaABC Action NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- AseanDocument1 pageAseanSagar SahaPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Narrative Report in Senior High School 2018 2019Document34 pagesFinal Narrative Report in Senior High School 2018 2019Maica Denise Sibal75% (4)

- ThePrinciplesofBiology 10045931Document674 pagesThePrinciplesofBiology 10045931jurebiePas encore d'évaluation

- Private Military CompaniesDocument23 pagesPrivate Military CompaniesAaron BundaPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab-Palestinian Relations E.karshDocument4 pagesArab-Palestinian Relations E.karshsamuelfeldbergPas encore d'évaluation

- Eo 11478Document3 pagesEo 11478Marla BarbotPas encore d'évaluation

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- FijiTimes - Feb 15 2013Document48 pagesFijiTimes - Feb 15 2013fijitimescanadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cultural and Trade Change Define This PeriodDocument18 pagesCultural and Trade Change Define This PeriodJennifer HoangPas encore d'évaluation

- What If Jose Rizal Did Not Challenge The Power of Colonizer SpainDocument2 pagesWhat If Jose Rizal Did Not Challenge The Power of Colonizer SpainHarry CalaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics IntroDocument2 pagesEthics IntroExekiel Albert Yee TulioPas encore d'évaluation

- ENG 49-Istoria Na BulgariaDocument34 pagesENG 49-Istoria Na BulgariaJerik SolasPas encore d'évaluation

- ContractDocument2 pagesContractRaffe Di Maio100% (1)

- Where Did The Dihqans GoDocument34 pagesWhere Did The Dihqans GoaminPas encore d'évaluation

- Two Party System PresentationDocument18 pagesTwo Party System PresentationMelanie FlorezPas encore d'évaluation

- Jan 28 Eighty Thousand Hits-Political-LawDocument522 pagesJan 28 Eighty Thousand Hits-Political-LawdecemberssyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bank Account - ResolutionDocument3 pagesBank Account - ResolutionAljohn Garzon88% (8)

- Solution 22Document2 pagesSolution 22Keisha ReynesPas encore d'évaluation

- Qutb-Ud-Din Aibak (Arabic:: Ud-Dîn Raziyâ, Usually Referred To in History As Razia SultanDocument8 pagesQutb-Ud-Din Aibak (Arabic:: Ud-Dîn Raziyâ, Usually Referred To in History As Razia SultanTapash SunjunuPas encore d'évaluation

- Mg350 All PagesDocument24 pagesMg350 All PagessyedsrahmanPas encore d'évaluation

- An Introduction To PostcolonialismDocument349 pagesAn Introduction To PostcolonialismTudor DragomirPas encore d'évaluation

- Property Syllabus With Case AssignmentsDocument5 pagesProperty Syllabus With Case AssignmentsJued CisnerosPas encore d'évaluation

- KFHG Gender Pay Gap Whitepaper PDFDocument28 pagesKFHG Gender Pay Gap Whitepaper PDFWinner#1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Liberties: Liberty of Abode and TravelDocument14 pagesCivil Liberties: Liberty of Abode and TravelJuris MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- 3.3 Gelar Awal NugrahaDocument10 pages3.3 Gelar Awal NugrahaGelar Awal NugrahaPas encore d'évaluation