Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

NAFTA Intellect Disconnect: Actual Costs and Benefits Versus Popular Perceptions

Transféré par

Latinos Ready To VoteTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

NAFTA Intellect Disconnect: Actual Costs and Benefits Versus Popular Perceptions

Transféré par

Latinos Ready To VoteDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The NAFTA Intellect

Disconnect

Actual Costs and Benefits

versus Popular Percep ons

RAYMOND ROBERTSON

The Bush School of Government and Public Service

WHATS THE TAKEAWAY?

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA),

which was initiated during the Republican administration

of George H.W. Bush and completed during the Democrat

administration of Bill Clinton, has been studied intensively

since it went into effect in 1994. Although an objective

review of the literature suggests that NAFTAs overall

effects have been small but positive for both Mexico and

the United States, Donald Trump has called it the worst

trade agreement ever. Others have claimed that NAFTA

bene its Mexico at the expense of the United States. This

brief revisits the evidence surrounding NAFTA, in

particular, and free trade agreements, in general.

There are many ways to evaluate trade agreements. Perhaps the best place to start is

by evaluating how well an

VOLUME 7 | ISSUE 3 | 2016

agreement achieved its stated goals. The Preamble to the

NAFTA lists ifteen goals.1

Most focus on increasing the

Overall, NAFTAs eects have

been small but posi ve for both

Mexico and the United States.

Free trade agreements lead to

increased exports and imports.

US exports are o en linked to

US jobs.

US consumers benefit

significantly from imports.

The overall benefits of trade

outweigh the costs.

volume of trade by reducing barriers to trade

and investment. It is clear that since NAFTA,

trade and investment have signi icantly increased between the three NAFTA countries.

In particular, goods traded between Mexico

and the United States increased by more than

a factor of ive between 1994 and 2015.2 US

exports to Mexico increased from $50.84 to

$235.7 billion, while US imports from Mexico

increased from $49.5 billion to $296.4 billion.

Goods traded between Canada and the United

States more than doubled over the same period. In other words, NAFTA appears to have

accomplished its primary objectives.

Since US imports from Mexico increased more

than our exports to Mexico, some have suggested that NAFTA and trade agreements like

NAFTA bene it our trading partners much

more than they bene it the United States. In

the case of Mexico, however, the facts do not

support the claim that Mexico has bene itted

more from NAFTA than the United States. In

fact, recent evidence suggests that earnings in

the two countries have grown at about the

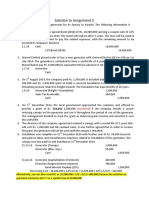

same rate since NAFTA.3 Adjusted for in lation, US GDP per capita increased steadily

(with the exception of the 2001 and 2008 recessions) from $36,566 to $51,486 between

1992 and 2015 (in constant 2010 US dollars).

Mexicos GDP growth has experienced larger

luctuations (including the December 1994

peso crisis), but over the same time period

Mexican GDP per capita increased from

$7,509 to $9,517 (in constant 2010 US dollars).4 See igure 1.

If Mexico gained more than the United States,

the gap between Mexican and US incomes

would have closed. On the contrary, the ratio

of Mexican to US GDP per capita fell from

Figure 1: GDP per Capita (constant 2010 US$)

Source: The World Bank

20.5% of US GDP per capita in 1992 to 18.5%

in 2015. This means that, at least in terms of

rising incomes, there seems to be no evidence

that Mexico has bene itted more than the

United States from NAFTA. See igure 2.

Furthermore, even though imports have

grown rapidly, much of the value of the US

imports from Mexico includes parts produced

in the United States that are exported to Mexico for assembly and then re-exported to the

United States. This arrangement, known as

outsourcing, increases the demand for US

workers doing higher-productivity work.

Figure 2: Ratio Mexican to US GDP per capita

(constant 2010 US$)

Source: The World Bank and authors calculations

The NAFTA Intellect Disconnect | Volume 7 | Issue 3| December 2016

EMPLOYMENT EFFECTS OF TRADE

But doesnt trade explain why families are

poor in the irst place? Doesnt importing lower-cost products cost jobs at home and lower

incomes? There are de initely some examples

of these adverse effects. Several mainstream

academics5 have produced empirical evidence

suggesting that imports are associated with

job losses. However, these effects are extremely localized and tend to affect lesseducated workers in especially hard-hit areas

(e.g. Detroit) and industries (e.g. apparel).

Even under the assumption that these effects

are entirely due to trade, the number of workers who have been adversely affected is in the

thousands while the number of people who

bene it from trade runs in the millions. The

overall bene its of trade outweigh the costs.

Furthermore, exports are unambiguously associated with job gains. Overall in 2015, 11.5

million US jobs were dependent on export

trade. Of those jobs, Texas, California, Washington, Illinois, and New York bene itted the

most with 2.8 million jobs, or 41% of jobs re-

lated to goods exports (not including service

exports).6

MEXICO AS PARTNER

Mexico is one of the United States most important trading partners. In 2015, total exports to Mexico accounted for 11.8% of overall US exports and total imports from Mexico

accounted for 11.5% of overall US imports.7

The total value of trade between Mexico and

the United States exceeded half a trillion dollars, and Mexico was the second largest market for US good exports. (Our other neighbor

and NAFTA trading partnerCanadawas

irst.)

The most accurate way to

think of the NAFTA

economic area is as one

combined market.

Trade with Mexico is especially important for

Texas. The automobile sector in particular in

Texas is very closely integrated with production in Mexico. Parts made in the United

States are shipped to Mexico for assembly

(often into more aggregated parts) and returned to the United States for additional processing by working Texans. As a result, the

most accurate way to think of the NAFTA economic area is as one integrated economy rather than three separate ones. That is, rather

than thinking of Mexico as a competitor, we

should think of Mexico as a partner in our national production process.

My own research supports this idea. Comparing the changes in employment in Mexico and

the United States over time and across differ-

The NAFTA Intellect Disconnect | Volume 7 | Issue 3| December 2016

Not all products imported from Mexico were

assembled from US parts. Mexico has also increased its exports of many other goods, including agricultural products (like avocados

and tomatoes) that show up on the dinner

tables of US consumers. In fact, trade theory

and empirical evidence both suggest that US

consumers bene it signi icantly from imports

from Mexico, in particular, and from imports

in general. Countries import goods that cost

less than products produced at home. The

availability of these cheaper products has

helped lower-income families stretch their

dollars and make ends meet.

ent manufacturing industries, the data show

that when employment expands in the United

States, it also expands in Mexico, and when it

contracts in the United States, it also contracts

in Mexico.8 In other words, Mexican and US

workers are complements and not substitutes

in production. The anecdotal evidence we observe in particular industries, such as the automotive industry, indicates that the strong

connections between US and Mexican employment are because they are part of the same

production process.

IMPLICATIONS

The potential for future gains from globalization for US consumers, producers, and workers, is very large. With the United States constituting only 5% of the world economy, 95%

of the world's consumers (with roughly three

fourths of the worlds purchasing power) lay

outside the United States. Research by the Peterson Institute estimates that eliminating the

remaining global trade barriers would increase the bene it America already enjoys

from trade by another 50%.9 Free trade

agreements are a proven way to improve economic conditions for both the United States

and our trading partners.

Raymond Robertson is a professor and holder of

the Helen and Roy Ryu Chair in Economics and

Government at the Bush School of Government

and Public Service. He serves as faculty

coordinator of the Mosbacher Ins tutes Program

in Integra on of Global Markets and is widely

published in the field of labor economics and

interna onal economics.

Notes:

1 The preamble to NAFTA is available at http://tech.mit.edu/Bulletins/

Nafta/00.preamble.

2 US Census Bureau, 2016. https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/

balance/c2010.html

3 Gandol i, Halliday, and Robertson (2016).

4 World Bank Development Indicators. http://data.worldbank.org/datacatalog/world-development-indicators

5 Kletzer, Lori (2001). Job loss from imports: Measuring the costs.

Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington D.C.; White,

Roger (2015). Making sense of anti-trade sentiment international trade

and the American worker. Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY; and David

H. Autor, David Dorn & Gordon H. Hanson (2016). The China shock:

Learning from labor market adjustment to large changes in trade. Annual

Review of Economics, 8(1), pp. 205-240.

6 http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/employment/ and

http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/build/groups/public/@tg_ian/

documents/webcontent/tg_ian_005503.pdf

7 Of ice of the United States Trade Representative, 2016.

8 Robertson, Raymond (2016). Are Mexican and U.S. workers

complements or substitutes? Unpublished Working Paper: The

Mosbacher Institute for Trade, Economics and Public Policy, The Bush

School of Government, Texas A&M University.

9 https://ustr.gov/issue-areas/economy-trade

ABOUT THE MOSBACHER INSTITUTE

The Mosbacher Ins tute was founded in 2009 to honor Robert A. Mosbacher, Secretary of Commerce from 1989

1992 and key architect of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Through our three core programsIntegra on

of Global Markets, Energy in a Global Economy, and Governance and Public Servicesour objec ve is to advance the

design of policies for tomorrows challenges.

Contact:

Cynthia Gause, Program Coordinator

Mosbacher Ins tute for Trade, Economics, and Public Policy

Bush School of Government and Public Service

4220 TAMU, Texas A&M University

College Sta on, Texas 778434220

To share your thoughts

on The Takeaway,

please visit

http://bit.ly/1ABajdH

Email: bushschoolmosbacher@tamu.edu

Website: h p://bush.tamu.edu/mosbacher

The views expressed here are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Mosbacher Ins tute, a center for

independent, nonpar san academic and policy research, nor of the Bush School of Government and Public Service.

The NAFTA Intellect Disconnect | Volume 7 | Issue 3| December 2016

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- How The United-States-Mexico-Canada Agreement Can Address U.S. Labor Market MismatchesDocument25 pagesHow The United-States-Mexico-Canada Agreement Can Address U.S. Labor Market MismatchesLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Improving K-12 Education For Hispanic Students in Las Vegas and BeyondDocument23 pagesImproving K-12 Education For Hispanic Students in Las Vegas and BeyondLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- US 2050 The Role of Institutions in Shaping Americas Future DemographicsDocument35 pagesUS 2050 The Role of Institutions in Shaping Americas Future DemographicsLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- The Decline in Mexican Migration To The US: Why Is Texas DifferenDocument56 pagesThe Decline in Mexican Migration To The US: Why Is Texas DifferenLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Health Care and Education Access of Transnational Children in MexDocument49 pagesHealth Care and Education Access of Transnational Children in MexLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Pew Research Center U.S. Unauthorized Immigrants Total Dips 2018-11-27Document78 pagesPew Research Center U.S. Unauthorized Immigrants Total Dips 2018-11-27Latinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- A Profile of Highly Skilled Mexican Immigrants in Texas and The United StatesDocument12 pagesA Profile of Highly Skilled Mexican Immigrants in Texas and The United StatesLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- The Latino Vote in 2020 by State and Voter RegistrationDocument10 pagesThe Latino Vote in 2020 by State and Voter RegistrationLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Harming Our Common Future: America's Segregated Schools 65 Years After BrownDocument44 pagesHarming Our Common Future: America's Segregated Schools 65 Years After BrownLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- The Latino Vote in 2018 by State and Voter RegistrationDocument8 pagesThe Latino Vote in 2018 by State and Voter RegistrationLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- The Economic Benefits of Latino Immigration: How The Migrant Hispanic Population's Demographic Characteristics Contribute To US GrowthDocument50 pagesThe Economic Benefits of Latino Immigration: How The Migrant Hispanic Population's Demographic Characteristics Contribute To US GrowthLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- The US Needs Workers Not A WallDocument9 pagesThe US Needs Workers Not A WallLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Revving Up The Deportation Machinery: Enforcement Under Trump and The PushbackDocument116 pagesRevving Up The Deportation Machinery: Enforcement Under Trump and The PushbackLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Texico: The Texas-Mexico Economy and Its Uncertain FutureDocument32 pagesTexico: The Texas-Mexico Economy and Its Uncertain FutureLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Renegotiating NAFTA in The Era of Trump: Keeping The Trade Liberalization in and The Protectionism OutDocument18 pagesRenegotiating NAFTA in The Era of Trump: Keeping The Trade Liberalization in and The Protectionism OutLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Fiscal Year 2017 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations ReportDocument18 pagesFiscal Year 2017 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations ReportLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- The Latino Vote in 2016 State-By-StateDocument9 pagesThe Latino Vote in 2016 State-By-StateLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Immigrants in Texas: Illegal Immigrant Conviction and Arrest Rates For Homicide, Sexual Assault, Larceny, and Other CrimesDocument8 pagesCriminal Immigrants in Texas: Illegal Immigrant Conviction and Arrest Rates For Homicide, Sexual Assault, Larceny, and Other CrimesLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- America Goes Polls 2016Document35 pagesAmerica Goes Polls 2016Matthew HamiltonPas encore d'évaluation

- Enforcement of The Immigration Laws To Serve The National Interest - DHSDocument6 pagesEnforcement of The Immigration Laws To Serve The National Interest - DHSIndy USAPas encore d'évaluation

- Implementing The Presidents Border Security Immigration Enforcement ImprovementDocument13 pagesImplementing The Presidents Border Security Immigration Enforcement Improvementjroneill100% (1)

- Migration Policy Report On DAPA: Illegal Immigrants Would Earn More If Court Approves Obama ActionDocument37 pagesMigration Policy Report On DAPA: Illegal Immigrants Would Earn More If Court Approves Obama ActionLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- The Outstate Effect - Why Clinton Lost The ElectionDocument16 pagesThe Outstate Effect - Why Clinton Lost The ElectionLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- THE $900 BILLION QUESTION: A Complete Fiscal Analysis of Donald J. Trump's Immigration Reform PlanDocument16 pagesTHE $900 BILLION QUESTION: A Complete Fiscal Analysis of Donald J. Trump's Immigration Reform PlanLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- Washington Post-Univision News National Survey of Hispanic VotersDocument17 pagesWashington Post-Univision News National Survey of Hispanic VotersLatinos Ready To VotePas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Assignment 2 SolutionDocument4 pagesAssignment 2 SolutionSobhia Kamal100% (1)

- Doing Business in Canada GuideDocument104 pagesDoing Business in Canada Guidejorge rodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Bwff1013 Foundations of Finance Quiz #3Document8 pagesBwff1013 Foundations of Finance Quiz #3tivaashiniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Berenstain Bears Blessed Are The PeacemakersDocument10 pagesThe Berenstain Bears Blessed Are The PeacemakersZondervan45% (20)

- (Rev.00) Offer For Jain Solar 15 HP Ac Pumping System - 03.12.2020Document5 pages(Rev.00) Offer For Jain Solar 15 HP Ac Pumping System - 03.12.2020sagar patolePas encore d'évaluation

- Manifesto: Manifesto of The Awami National PartyDocument13 pagesManifesto: Manifesto of The Awami National PartyonepakistancomPas encore d'évaluation

- Golden Tax - CloudDocument75 pagesGolden Tax - Cloudvarachartered283Pas encore d'évaluation

- Disinvestment Policy of IndiaDocument7 pagesDisinvestment Policy of Indiahusain abbasPas encore d'évaluation

- Titan MUX User Manual 1 5Document158 pagesTitan MUX User Manual 1 5ak1828Pas encore d'évaluation

- War, Peace and International Relations in Contemporary IslamDocument7 pagesWar, Peace and International Relations in Contemporary IslamJerusalemInstitute100% (1)

- MELENDEZ Luis Sentencing MemoDocument9 pagesMELENDEZ Luis Sentencing MemoHelen BennettPas encore d'évaluation

- Denmark Trans Fats LawDocument2 pagesDenmark Trans Fats LawPerwaiz KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- DuplicateDocument4 pagesDuplicateSakshi ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- Quiz Week 3 AnswersDocument5 pagesQuiz Week 3 AnswersDaniel WelschmeyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Mary Rieser "Things That Should Not Be"Document22 pagesMary Rieser "Things That Should Not Be"Tony OrtegaPas encore d'évaluation

- ISO 13485 - Carestream Dental - Exp 2022Document2 pagesISO 13485 - Carestream Dental - Exp 2022UyunnPas encore d'évaluation

- Lucas TVS Price List 2nd May 2011Document188 pagesLucas TVS Price List 2nd May 2011acere18Pas encore d'évaluation

- Schnittke - The Old Style Suite - Wind Quintet PDFDocument16 pagesSchnittke - The Old Style Suite - Wind Quintet PDFciccio100% (1)

- Chapter Two 2.1 Overview From The Nigerian Constitution (1999)Document7 pagesChapter Two 2.1 Overview From The Nigerian Constitution (1999)Ahmad Khalil JamilPas encore d'évaluation

- LPB Vs DAR-DigestDocument2 pagesLPB Vs DAR-DigestremoveignorancePas encore d'évaluation

- STRONG vs. REPIDEDocument1 pageSTRONG vs. REPIDENicolo GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Accreditation of NGOs To BBIsDocument26 pagesAccreditation of NGOs To BBIsMelanieParaynoDaban100% (1)

- Educations of Students With DisabilitiesDocument6 pagesEducations of Students With Disabilitiesapi-510584254Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter Two: A Market That Has No One Specific Location Is Termed A (N) - MarketDocument9 pagesChapter Two: A Market That Has No One Specific Location Is Termed A (N) - MarketAsif HossainPas encore d'évaluation

- Format For Computation of Income Under Income Tax ActDocument3 pagesFormat For Computation of Income Under Income Tax ActAakash67% (3)

- G. M. Wagh - Property Law - Indian Trusts Act, 1882 (2021)Document54 pagesG. M. Wagh - Property Law - Indian Trusts Act, 1882 (2021)Akshata SawantPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Pop Culture On PoliticsDocument3 pagesImpact of Pop Culture On PoliticsPradip luitelPas encore d'évaluation

- SEMESTER-VIDocument15 pagesSEMESTER-VIshivam_2607Pas encore d'évaluation

- COMMERCIAL CORRESPONDENCE ADDRESSINGDocument44 pagesCOMMERCIAL CORRESPONDENCE ADDRESSINGKarla RazvanPas encore d'évaluation

- 0.US in Caribbean 1776 To 1870Document20 pages0.US in Caribbean 1776 To 1870Tj RobertsPas encore d'évaluation