Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

About C. V. Raman

Transféré par

IrfanCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

About C. V. Raman

Transféré par

IrfanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

C. V.

Raman

Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman[2] (7 November 1888 21 November 1970), an

Indian physicist born in the former Madras Province in India, carried out groundbreaking work in the field of light scattering which earned him the 1930 Nobel Prize

for Physics. He discovered that when light traverses a transparent material, some of

the deflected light changes in wavelength. This phenomenon, subsequently known

as Raman scattering, results from the Raman effect.[3] In 1954 India honoured him

with its highest civilian award, the Bharat Ratna

Early years

C.V.Raman was born to a Tamil Brahmin Iyer family in Thiruvanaikaval, Trichinopoly, (presentday Tiruchirapalli), Madras Presidency Tamil Nadu, in British India to Parvati Amma.

Family

Raman's father initially taught in a school in Thiruvanaikaval, became a lecturer of mathematics

and physics in Mrs. A.V. Narasimha Rao College, Vishakapatnam (then Vishakapatnam) in the

Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, and later joined Presidency College in Madras (now Chennai).[1][6]

Early education

At an early age, Raman moved to the city of Visakhapatnam and studied at St. Aloysius AngloIndian High School. Raman passed his matriculation examination at the age of 11 and he passed

his F.A. examination (equivalent to today's Intermediate exam, PUC/PDC and +2) with a

scholarship at the age of 13.

In 1902, Raman joined Presidency College in Madras where his father was a lecturer in

mathematics and physics.[7] In 1904 he passed his Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) examination: He stood

first and won the gold medal in physics. In 1907 he gained his Master of Arts (M.A.) degree with

the highest distinctions.[1]

Career

In 1917, Raman resigned from his government service after he was appointed the first Palit

Professor of Physics at the University of Calcutta. At the same time, he continued doing research

at the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS), Calcutta, where he became the

Honorary Secretary. Raman used to refer to this period as the golden era of his career. Many

students gathered around him at the IACS and the University of Calcutta.

C. V. Raman

Energy level diagram showing the states involved in Raman signal

On 28 February 1928, Raman led experiments at the IACS with collaborators, including K. S.

Krishnan, on the scattering of light, when he discovered what now is called the Raman effect. [8] A

detailed account of this period is reported in the biography by G. Venkatraman. [9] It was instantly

clear that this discovery was of huge value. It gave further proof of the quantum nature of light.

Raman had a complicated professional relationship with K. S. Krishnan, who surprisingly did not

share the award, but is mentioned prominently even in the Nobel lecture.[10]

Raman spectroscopy came to be based on this phenomenon, and Ernest Rutherford referred to it

in his presidential address to the Royal Society in 1929. Raman was president of the 16th session

of the Indian Science Congress in 1929. He was conferred a knighthood, and medals and

honorary doctorates by various universities. Raman was confident of winning the Nobel Prize in

Physics as well, but was disappointed when the Nobel Prize went to Owen Richardson in 1928

and to Louis de Broglie in 1929. He was so confident of winning the prize in 1930 that he

booked tickets in July, even though the awards were to be announced in November, and would

scan each day's newspaper for announcement of the prize, tossing it away if it did not carry the

news.[11] He did eventually win the 1930 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his work on the scattering of

light and for the discovery of the Raman effect".[12] He was the first Asian and first non-white to

receive any Nobel Prize in the sciences. Before him Rabindranath Tagore (also Indian) had

received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913.

Raman and Suri Bhagavantam discovered the quantum photon spin in 1932, which further

confirmed the quantum nature of light.[13]

Raman had association with the Banaras Hindu University in Varanasi; he attended the

foundation ceremony of BHU[14] and delivered lectures on "Mathematics" and "Some new paths

in physics" during the lecture series organised at BHU from February 5 to 8, 1916. [15] He also

held the position of permanent visiting professor at BHU.[16]

During his tenure at IISc, he recruited the talented electrical engineering student, G. N.

Ramachandran, who later went on to become a distinguished X-ray crystallographer.

C. V. Raman

Raman also worked on the acoustics of musical instruments. He worked out the theory of

transverse vibration of bowed strings, on the basis of superposition velocities. He was also the

first to investigate the harmonic nature of the sound of the Indian drums such as the tabla and the

mridangam.[17] He was also interested in the properties of other musical instruments based on

forced vibrations such as the violin. He also investigated the propagation of sound in whispering

galleries.[18] Raman's work on acoustics was an important prelude, both experimentally and

conceptually, to his later work on optics and quantum mechanics.[19]

Raman and his student, Nagendra Nath, provided the correct theoretical explanation for the

acousto-optic effect (light scattering by sound waves), in a series of articles resulting in the

celebrated RamanNath theory.[20] Modulators, and switching systems based on this effect have

enabled optical communication components based on laser systems.

Raman was succeeded by Debendra Mohan Bose as the Palit Professor in 1932. In 1933, Raman

left IACS to join Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore as its first Indian director.[21] Other

investigations carried out by Raman were experimental and theoretical studies on the diffraction

of light by acoustic waves of ultrasonic and hypersonic frequencies (published 19341942), and

those on the effects produced by X-rays on infrared vibrations in crystals exposed to ordinary

light.

He also started the company called Travancore Chemical and Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (now

known as TCM Limited) which manufactured potassium chlorate for the match industry[22] in

1943 along with Dr. Krishnamurthy. The Company subsequently established four factories in

Southern India. In 1947, he was appointed as the first National Professor by the new government

of Independent India.[23]

In 1948, Raman, through studying the spectroscopic behaviour of crystals, approached in a new

manner fundamental problems of crystal dynamics. He dealt with the structure and properties of

diamond, the structure and optical behaviour of numerous iridescent substances (labradorite,

pearly feldspar, agate, opal, and pearls). Among his other interests were the optics of colloids,

electrical and magnetic anisotropy, and the physiology of human vision.

Raman retired from the Indian Institute of Science in 1948 and established the Raman Research

Institute in Bangalore, Karnataka, a year later. He served as its director and remained active there

until his death in 1970, in Bangalore, at the age of 82.

During a voyage to Europe in 1921, Raman noticed the blue colour of glaciers and the

Mediterranean sea. He was motivated to discover the reason for the blue colour. Raman carried

out experiments regarding the scattering of light by water and transparent blocks of ice which

explained the phenomenon.

Raman employed monochromatic light from a mercury arc lamp which penetrated transparent

material and was allowed to fall on a spectrograph to record its spectrum. He detected lines in the

spectrum which he later called Raman lines. He presented his theory at a meeting of scientists in

Bangalore on 16 March 1928, and won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930.

C. V. Raman

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Limitations of Learning by Discovery - Ausubel PDFDocument14 pagesLimitations of Learning by Discovery - Ausubel PDFOpazo SebastianPas encore d'évaluation

- Khutba Before Majlis PDFDocument2 pagesKhutba Before Majlis PDFIrfan71% (7)

- 3700 RES 5.5.1 Install GuideDocument38 pages3700 RES 5.5.1 Install Guidejlappi100% (1)

- Chem 1211 Lab ReportDocument9 pagesChem 1211 Lab Reportansleybarfield0% (1)

- READMEDocument3 pagesREADMEIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Yaris PDFDocument23 pagesYaris PDFHarishPas encore d'évaluation

- Syll. Dip. in Callig. & Grafic Design PDFDocument2 pagesSyll. Dip. in Callig. & Grafic Design PDFIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Prof Ali Mohammed NaqiDocument8 pagesProf Ali Mohammed NaqiIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- 3-D Printing Training ProgramDocument1 page3-D Printing Training ProgramIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Certificate in Recitation of Quran - QiratDocument2 pagesCertificate in Recitation of Quran - QiratIrfan AliPas encore d'évaluation

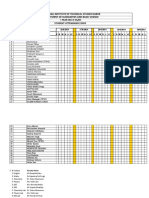

- Sec D Attendence Record 26 Aug - 5 SepDocument4 pagesSec D Attendence Record 26 Aug - 5 SepIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

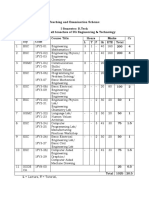

- First Year Scheme and Syllabus Effective From 2012-13Document21 pagesFirst Year Scheme and Syllabus Effective From 2012-1350849Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anti GravitatorDocument1 pageAnti GravitatorIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Basics of Solar Power For Producing ElectricityDocument5 pagesThe Basics of Solar Power For Producing ElectricityJason HallPas encore d'évaluation

- 2011-2012 Ec Circuit Analysis and SynthesisDocument1 page2011-2012 Ec Circuit Analysis and SynthesisIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Completed FormDocument1 pageCompleted FormIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Diffraction Grating1 PDFDocument3 pagesDiffraction Grating1 PDFIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods of Wiring: Three-Plate MethodDocument2 pagesMethods of Wiring: Three-Plate MethodIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 and 4 TH Sem Syllabus of ECDocument60 pages3 and 4 TH Sem Syllabus of ECIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Muslim Antisemitism and Anti-Zionism in PDFDocument4 pagesMuslim Antisemitism and Anti-Zionism in PDFIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Power System Modelling LabDocument1 pagePower System Modelling LabIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Physics Lab Practical Exam - 2018Document1 pagePhysics Lab Practical Exam - 2018IrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Scheme 2Document3 pagesScheme 2IrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Faculty Development Programme On Recent Trends in Nano-Electronics (RTNE-2018)Document1 pageFaculty Development Programme On Recent Trends in Nano-Electronics (RTNE-2018)IrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering Physics - I LabDocument1 pageEngineering Physics - I LabIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering Physics - I LabDocument2 pagesEngineering Physics - I LabIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Analysis of The Week - 27th July 2018Document5 pagesPolitical Analysis of The Week - 27th July 2018IrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- BTech - Syllabus EE 3-8 SemDocument52 pagesBTech - Syllabus EE 3-8 SemNikhil BhatiPas encore d'évaluation

- A New EarthDocument125 pagesA New EarthDaniel KrierPas encore d'évaluation

- A Gift of Ghazals - Louis WernerDocument8 pagesA Gift of Ghazals - Louis WernerTariq MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Electric MotorsDocument12 pagesElectric MotorsVirajitha MaddumabandaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Set A (Cement) PDFDocument1 pageSet A (Cement) PDFIrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To IC Technology Rev 5Document0 pageIntroduction To IC Technology Rev 5manojmanojsarmaPas encore d'évaluation

- STD XTH Geometry Maharashtra BoardDocument35 pagesSTD XTH Geometry Maharashtra Boardphanikumar50% (2)

- TMT Boron CoatingDocument6 pagesTMT Boron Coatingcvolkan1100% (2)

- FI Printing Guide Vinyl-303Document1 pageFI Printing Guide Vinyl-303tomasykPas encore d'évaluation

- Residual Alkalinity Nomograph by John Palmer PDFDocument1 pageResidual Alkalinity Nomograph by John Palmer PDFcarlos pablo pabletePas encore d'évaluation

- Zener Barrier: 2002 IS CatalogDocument1 pageZener Barrier: 2002 IS CatalogabcPas encore d'évaluation

- Class VI (Second Term)Document29 pagesClass VI (Second Term)Yogesh BansalPas encore d'évaluation

- Hindu Temples Models of A Fractal Universe by Prof - Kriti TrivediDocument7 pagesHindu Temples Models of A Fractal Universe by Prof - Kriti TrivediAr ReshmaPas encore d'évaluation

- MIL-PRF-85704C Turbin CompressorDocument31 pagesMIL-PRF-85704C Turbin CompressordesosanPas encore d'évaluation

- User's Manual HEIDENHAIN Conversational Format ITNC 530Document747 pagesUser's Manual HEIDENHAIN Conversational Format ITNC 530Mohamed Essam Mohamed100% (2)

- Simple Harmonic Oscillator: 1 HamiltonianDocument10 pagesSimple Harmonic Oscillator: 1 HamiltonianAbdurrahman imamPas encore d'évaluation

- 5R55W-S Repair DiagnosisDocument70 pages5R55W-S Repair Diagnosisaxallindo100% (2)

- CCNA2 Lab 7 3 8 enDocument6 pagesCCNA2 Lab 7 3 8 enapi-3809703100% (1)

- ITECH1000 Assignment1 Specification Sem22014Document6 pagesITECH1000 Assignment1 Specification Sem22014Nitin KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- API2000 Tank Venting CalcsDocument5 pagesAPI2000 Tank Venting Calcsruhul01Pas encore d'évaluation

- EP 1110-1-8 Vo2 PDFDocument501 pagesEP 1110-1-8 Vo2 PDFyodiumhchltPas encore d'évaluation

- TOEC8431120DDocument522 pagesTOEC8431120Dvuitinhnhd9817Pas encore d'évaluation

- ATR4518R2Document2 pagesATR4518R2estebanarca50% (4)

- VFS1000 6000Document126 pagesVFS1000 6000krisornPas encore d'évaluation

- Bootloader3 PDFDocument18 pagesBootloader3 PDFsaravananPas encore d'évaluation

- Solved - Which $1,000 Bond Has The Higher Yield To Maturity, A T...Document4 pagesSolved - Which $1,000 Bond Has The Higher Yield To Maturity, A T...Sanjna ChimnaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Mbs PartitionwallDocument91 pagesMbs PartitionwallRamsey RasmeyPas encore d'évaluation

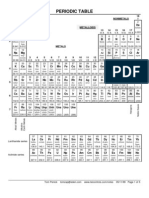

- Periodic Table and AtomsDocument5 pagesPeriodic Table and AtomsShoroff AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Parts Catalog: Parts - Sales - Service - RestorationsDocument32 pagesParts Catalog: Parts - Sales - Service - RestorationsJean BelzilPas encore d'évaluation

- Fiber SyllabusDocument1 pageFiber SyllabusPaurav NayakPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab 3.1 - Configuring and Verifying Standard ACLsDocument9 pagesLab 3.1 - Configuring and Verifying Standard ACLsRas Abel BekelePas encore d'évaluation

- 1.project FullDocument75 pages1.project FullKolliparaDeepakPas encore d'évaluation