Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Victorianstudies.56.3.433 Fotografija

Transféré par

Gile BrankovicCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Victorianstudies.56.3.433 Fotografija

Transféré par

Gile BrankovicDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Murder in Black and White: Victorian Crime Scenes and the Ripper Photographs

Author(s): Megha Anwer

Source: Victorian Studies, Vol. 56, No. 3, Special Issue: Papers and Responses from the

Eleventh Annual Conference of the North American Victorian Studies Association (Spring

2014), pp. 433-441

Published by: Indiana University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/victorianstudies.56.3.433

Accessed: 16-05-2016 15:41 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://about.jstor.org/terms

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted

digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about

JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Indiana University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Victorian

Studies

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Murder in Black and White:

Victorian Crime Scenes and the Ripper Photographs

Megha Anwer

he paucity of criticism on the photographic evidence of Jack

the Rippers murders is striking and surprising, particularly

given that these images amount to one of the first visual documentations of what are now called sex crimes. Even Robert McLaughlins pioneering study The First Jack the Ripper Victim Photographs falls

short of adequately decoding whats really going on in the pictures

themselves, in part because he seems less interested in the content of

the photographs than in the biographical details of the photographers

who created them. This essay hopes to address and correct this interpretive gap. Through a close analysis of the few Ripper photographs

that still survive, I seek to recover the representational codes governing

the visual, spatial, and gender politics of these images. In the first

section I examine the postmortem portraits of the victims. In the

second, I explore the continuities I see between the full-body mortuary

photographs of the victims and a broader Victorian art aesthetic. In

the third and final section I study closely the single crime-scene photograph of the body of Mary Kelly (the Rippers fifth victim).1

I.

Suren Lalvani argues that in the nineteenth century, photography was believed to be an apparatus of insight (50) that could

reveal, in the words of Naomi Rosenblum, personality, intellect, and

A bstract: The paucity of criticism on photographic evidence of the Jack the Ripper

murders is surprising, particularly given that these images amount to a first-time visual

documentation of what are now called sex crimes. This essay attempts to correct this

interpretive lag. Through a close analysis of the few Ripper photographs that still

survive, I seek to recover the representational codes governing the buried visual,

spatial, and gender politics implicated in these photographs. In doing so I challenge

the bureaucratic filter of official investigations, police reports, and media reportage

that blinds us to the affective dimension of documenting reality.

spring 2014

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

434

Megha Anwer

character...through the depiction of facial configuration and expression (Rosenblum 39). The human face was believed to confess the

corruptions of the soulif not always to the naked human eye, then to

the camera, which was thought to possess a magical power to elicit our

darkest secrets. The conviction that criminality could be detected

from photographed features was central to the assembling of the

rogues galleries of police photographs of criminal suspects in

England, France, and America.

The bulk of the Ripper photographs resemble criminal mug

shots in that the camera seems to gaze steadfastly at the victims faces

and focus on little elsewe rarely see a full-body picture, and certainly

none (barring the Mary Kelly photograph) of the body located within

the crime scene itself.2 Disconcertingly, by fixating on the victims facial

physiognomy, the camera transforms these forensic photographs into

pure portraits purged of nearly all crime-scene traces. The effect can

imply that crime is somehow resting immanently within the physiological contours of the victim herself, as if there were something in her

appearance that led to her victimization. The prostitute thus becomes

less the crimes victim and more its provocation.

Read in this light, the ghostly portraits of the Rippers victims

seem to operate more as mug shots for a police lineup than as bodies

photographed for details of the injuries they have suffered. Furthermore, they resemble portraits of sleeping women, photographed clandestinely, voyeuristically, without their knowledge. All that is required

of us, the viewers, is a slight associative legerdemain, and the sleeping

women transform into the women who sleep around. The mortuary

photographs, in that case, function less as objective documents that

supplement textual inventories of violence committed by the Ripper

and more as an archive profiling streetwalkersa female counterpart

to the predominantly male mug-shot compilations of criminal types.

What is being diagnosed through the markers available inside these

photographs is not the Rippers sexual pathology, but rather the

provocative sexual profligacy of his female victims. These portrait

photographs thus offer a moral explanation for why these prostitutes

were killedprecisely because they were prostitutes.

Lalvani points out that Victorian photography was entrenched

in the politics of upward mobility. Lower-class men and women made

their way into studios where they could momentarily conceal their

working-class backgrounds and be made visible in the light of their

victorian studies / Volume 56, no. 3

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Murder in Black and White

435

aspirations (69). This privilege of temporarily inhabiting desired social

identities is typically not extended to sex workers, however. In fact, the

Ripper victim portraits do just the reverse: they everlastingly freeze these

women, who from all accounts were part- rather than full-time prostitutes, into a singular identity. Jennifer Green-Lewis suggests that every

instance of photography has a potential to be used against its subject

(180); the photographs of the Rippers victims are, indeed, used against

them as a means to typecast them, to pin them down as prostitutesas

criminalized and illegal citizens.

II.

Images of the faces of dead women were, of course, far from

unusual in Victorian England. In Idols of Perversity, Bram Dijkstra lays

bare the nineteenth centurys cult of feminine invalidism (28), in

which physical vigor in women was associated with dangerous, masculinising attitudes (26) and women were encouraged to appear starving

and consumptive as proof of their superior breeding, feminine refinement, and spiritual purity. The sheer number of paintings that depict

women in various stages of abject physical degeneration (28) offers a

parallel and complementary narrative through which to read and

understand the Ripper photographs. Paintings that mysticized and

eroticized dying women may appear sedate, exalting, and even alluring

in comparison to the unbridled maniacal violence suggested by the

Ripper photographs. Still, a certain affinity between them should not

pass unnoticed. Nineteenth-century art had consolidated and celebrated a sadistic culture that pushed women into self-sacrifice to the

point of deatha process that transferred responsibility for the womans

wellbeing to her husband. Womens self-chosen degeneration in

marriage thus was the key to their husbands spiritual and physical

success and long life (Dijkstra 30): behind every successful man is a

decaying woman. And painters and poets relentlessly recorded and

disseminated images commemorating and in effect validating the

slow, sacrificial decay by which women of virtue waste away.

This kind of artistic violence that aestheticizes dying women, I

would argue, resembles the necrophiliac, murderous outpourings of

the Ripper photographs. The full-body postmortem photograph of

Catherine Eddowes could easily be replaced by Albert Von Kellers

1885 painting Study of a Dead Woman, and we would barely notice

spring 2014

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

436

Megha Anwer

the difference. Their gaping mouths, sagging breasts, and sunken abdomens allow these visual documents to function as paired mirror images

of one another. What is remarkable about this surgical iconography is

that it cuts across distinct modes and genres of visual documentation.

Both nineteenth-century medical portmortem photographs and

painted portraits intended for galleries and drawing rooms share

many of the same characteristics. These shared codes of representation produce a hybrid form characterized at once by a pseudoscientific

exactitude in painting and by a morbid aestheticization in medical and

mortuary photography.

In the case of the Ripper mortuary photographs, the images

attest to the obliterative artistic might and agency of the Ripper,

while also acknowledging the technical prowess of medical personnel,

the doctors and coroners engaged, with just as much skill as the Ripper,

in reassembling these dismembered and mutilated female bodies. As

Judith Walkowitz notes in City of Dreadful Delight, the Ripper murders

exacerbated popular suspicion of anatomists. Given this atmosphere

of hostility toward medical men, the surgeons involved in conducting

postmortems on the Ripper victims were eager to differentiate their

profession and medical knowledge from the Rippers handiwork. They

humbly asserted that they themselves could not perform such injuries

as efficiently and quickly as the Ripper had (Walkowitz 211). The postmortem photographs may thus be understood as participating in and

contributing to the medical communitys attempts at moral self-

rehabilitation. The victim photographs are evidence of the salutary

functions of medicine, its ability to piece and suture back beleaguered

body parts and recover a semblance of the human contours of a woman

disfigured and mutilated beyond recognition. The doctors may not

have had the knowledge to inflict injuries as masterfully as the Ripper,

yet they had the expertise and know-how to reverse the damage, to

repair the bodies left in his wake. The photographs therefore transform these women into canvases upon which menwith competing

motivationsprove their aesthetic and scientific mastery.

III.

Photography in the Victorian period participated vigorously in

consolidating the post-Enlightenment perception of a coherent autonomous subject (Pultz 716). Photographs championed the idea of a freely

victorian studies / Volume 56, no. 3

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Murder in Black and White

437

observing individual who also had infinite access to the signs and means

of self-representationa right that had until recently been the exclusive

preserve of the aristocracy. The photograph of Mary Kelly at the crime

scene in Millers Court, however, unnervingly disrupts this coherently

self-fashioning function of photography. If, as Peter J. Hutchings reminds

us, a reduction of reality to what can be seen, or measured...involves a

will to mastery (241), then surely the photograph of Mary Kellys

disaggregated body brings to light an inverse phenomenon: the awareness that even if something can be documented, this does not guarantee

that it can be grasped or understood.

In contrast to the mortuary portraits of the Rippers other

victims, Mary Kellys brutalized body and disfigured features signal a

chilling loss of identity or identification. Her hopelessly anonymous,

vanished face becomes infinitely transposable: the defaced prostitute

could be literally anyone. In this case the photograph, like the butchered body, does not in the least facilitate a cohering identification

function. Instead, it sets in motion a reeling sense of instability and

exchangeable selves, what Daniel Novak calls an economy of interchangeable people brought on by the mechanics of effacement (30).

This breakdown of distinction between the self and the sexual

otherthe prostituteelicits our visceral response of incomprehension mingled with terror. To use Julia Kristevas theory of horror,

Kellys mangled corpse, seen without God and outside of science, is

the utmost of abjection. It is death infecting life (4).

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes suggests that photographs

invariably convey the idea of death in the future (101). When we look

at the photograph of a loved one after she has died, temporality blurs

in such a way that we transpose the knowledge of her death into the

past and think: she is going to die. [We] shudder...over a catastrophe

which has already occurred. Whether or not the subject is already dead,

every photograph is this catastrophe (96). Mary Kellys photograph

does something even more devastating. Its empty, dismantled orifices

markers of the Rippers violencepredict not death, but the traumas

of the body postmortem: the Rippers ripping prefigures the process of

slicing, opening up, and investigating the body during autopsy procedures. What this photograph reproduces to infinity is not a moment

that could never be repeated existentially (Barthes 4), but one that

will in fact be reenacted the very instant after this photograph has

been takenthe body will be removed from the crime scene, placed

spring 2014

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

438

Megha Anwer

on a surgical table, taken apart, and then repackaged all over again. If

the abject revolts us because it is (as Kristeva suggests) death infecting

life, then this photograph is nauseating twice over.

Ironically, in our attempt to detect and decipher death, we

shift and move about the dead body (and with it, figuratively, the traces

of the crime scene) into multiple, discontinuous spaces: from the

venue of the crime to the postmortem room, and thence to the morgue,

the graveyard, the police station, the courtroom. The crime scene

morphs into something variable, portable, and locationally nonspecific, spilling out in all directions. Confronted with this fluidity and

expansibility of the scene, the crime-scene photograph struggles to

fixate, stabilize, and localize the crime through chemicals on a piece

of paper. Thus to photograph crime is not just to document it, but also

to hope to contain its threatened overflow, to limit its proliferative

potential and neutralize its danger. The forensic photograph is meant

at least in part to disconnect and exclude the contents of the photographic frame from the world that lies beyond its bordersthe very

world that must be protected from being turned into a crime scene.

Kellys crime-scene photograph, however, seems to resist and

sabotage the drive to contain it. If photography often attempts to decontextualize the event, to disjoin it from history, then Kellys photograph

reinstates itself within history. Among other things, this photograph

presents a direct challenge to Victorian journalism and media hype

regarding the missing organ at the time of Kellys murder. In the

aftermath of the murders discovery, rumors about the Ripper having

stolen his fifth victims body parts enveloped the city. The truncated

inquest, which revealed very little information about the body, sent

journalists into a febrile goose chase to find out what parts of the body

were missing (Curtis 19697). In this atmosphere of media mayhem,

the photograph seems to discourage such fetishist preoccupations,

which distracted the populace from confronting the truly horrific

condition of Kellys body as found. To focus on the absent body part

becomes a self-deluding detour that allows us to turn a blind eye to the

remnants of the savaged body left behind by the murderer. The photograph offers a very different visual counternarrative to such journalistic pieces, forcing the viewer to take stock of the sheer evidence of

Kellys misshapen body. In fact, the sight of her organs ranged on the

bedside table undermines any diversionary tactics to fixate on missing

parts. When a human being is reduced to the sum of her hewn and

victorian studies / Volume 56, no. 3

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Murder in Black and White

439

scattered body parts, it becomes impossible to fetishize any one missing

organ. The question we are forced to tackle when we see the photograph is not what is missing, but rather, what is left?

In this sense the terrible photograph of what remains of Mary

Kellys body visually defies Victorian Londons claims to civilizational

supremacy. The image exposes journalists as inept documenters of a

crisis: they remain preoccupied with reporting irrelevant, sensational

details, missing the forest for the trees. It mocks our belief in humanitys

claimed superiority over the beast, and unravels the distinction

between medical knowledge and the hatchet skills of slaughterers; the

battered body on the bed could just as well be the butchered carcass of

an animal. Walter Benjamin suggested that Eugne Atgets photographs of Paris were reminiscent of the scene of a crimethe morbid

gloom over the night city in his work evoked a deathly, murderous

crime scene (Salzani 169; MacFarlane 23). Kellys photograph is literally an image of a crime scene, but one that questions and undermines

many of its societys premises and presumptions.

Yet even as the photograph does all this, it can also enhance our

emotional sense and experience of the crime scene. For me, the photographs punctumthe preexistent yet unnoticed detail that provokes a

tiny shock (Barthes 49), the incongruous gesture [that]...arrest[s] my

gaze (51)resides in the fact that Mary Kellys face is bizarrely turned

toward the camera. She is looking directly at us through her battered,

swollen eyes. This creates the eerie sensation that she, a dead woman, has

shifted the angle of her head to gaze directly into the cameraas though

to return the photographers gaze. It makes one imagine Kelly turning

her head to watch her murderer walk about the room as he prepared to

mutilate his victim. Somehow, this innocuous minor detail has the

capacity to make us alive to her torment much more than any postmortem

report can. The past tense in which the report catalogues the victims injuriesThe bed clothing...was saturated with blood... the face was

gashed in all directions...both breasts were more or less removed (Dr.

Bonds Post Mortem, emphases added)turns the human being into a

distanced, remote entity, an object of clinical reportage.3 Her face looking

straight at us in the photograph, on the other hand, alerts and returns us

to the real Mary Kelly as a (once) living and intact human being, as a

woman who changes her posture in response to the activities in the room,

who turns her head and rests her hand on her abdomen, and who gazes at

a person, perhaps even at her assailant.

spring 2014

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

440

Megha Anwer

If we read this visual text for its forensic aestheticswhich

emerge when an object of forensic analysis is removed from its legal

and criminalistic connotations and addressed or reframed as a work of

art (Jones 174)it hits us with a power it was never meant to have

(Rugoff 184). In this context, this photograph augments the crime

scene so that we begin to notice things that would have no place in a

juridical context. Even as the crime scene in the photograph is extraneous to the ordered space of the everyday (Wollen 23)the bloody

chaos it records marks it as a calamitous momentit is still ridden by

an overwhelming sense of the banal and vacuous, the hyperreal. If we

look at the image long enough we will begin to notice the wooden slats

of the cot upon which the mattress rests, the design of the bedpost, the

grimy walls of the roomthings that constitute the ordinary, everyday

drabness, the austerity and minimalism, of working-class dwellings.

The usual bureaucratic filter of official investigations, police

reports, and even media reportage blinds us to the affective dimension

of depictions of crime scenes. In this essay, through revisiting the

Ripper photographs, I have tried at once to demonstrate the operations of this blindnessto show why we do not normally see certain

details and qualities in such imagesand to undo those operations, to

allow us to see that which we would have missed.

Purdue University

NOTES

I would like to thank Emily Allen, Dino Felluga, and Lance Duerfahrd for helping me

through different stages of this essay. A special thank you to Daniel Novak, Paul

Deslandes, and Marlene Tromp for suggesting future directions for this project.

1

Mary Kellys crime-scene photograph is reproduced in Begg (14849).

2

Refer, for instance, to the mortuary photographs of Martha Tabram, Mary

Ann Nichols, and Catherine Eddowes. The mortuary photographs of Tabram and

Nichols are reproduced in Eddleston (11, 19). Postmortem photographs of Eddowes

can be found on the Casebook: Jack the Ripper website at <http://www.casebook.org/

victims/eddowes.html>.

3

Dr. Thomas Bond wrote the postmortem report on Mary Kelly after examining her remains. The report was lost until as recently as 1987, when it was returned

anonymously to Scotland Yard. For a longer discussion of the medical and media

reportage of the Rippers victims, see Curtis (21337).

victorian studies / Volume 56, no. 3

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Murder in Black and White

441

WORKS CITED

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill, 1981.

Benjamin, Walter. A Short History of Photography. Screen 13.1 (1972): 526.

Caputi, Jane. The Sexual Politics of Murder. Gender and Society 3.4 (1989): 43756.

Curtis, L. Perry. Jack the Ripper and the London Press. New Haven: Yale UP, 2001.

Dijkstra, Bram. Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-De-Sicle Culture. New

York: Oxford UP, 1986.

Dr. Bonds Post Mortem on Mary Kelly. Casebook: Jack the Ripper. Ed. Stephen P. Ryder.

19962013. <http://www.casebook.org/official_documents/pm-kelly.html>.

Eddleston, John J. Jack The Ripper: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2001.

Green-Lewis, Jennifer. Framing the Victorians: Photography and the Culture of Realism.

Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1996.

Hutchings, Peter. Modern Forensics: Photography and Other Suspects. Cardozo Studies

in Law and Literature 9.2 (1997): 22943.

Jones, Bronwyn K. Performing Psychopathology: Crime Scene Photography, Forensic

Aesthetics, and Performative Knowledge in the Contemporary Serial Killer Narrative. Diss. Northwestern U. 2004.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia UP, 1982.

Lalvani, Suren. Photography, Vision, and the Production of Modern Bodies. Albany: State U

of New York P, 1996.

McLaughlin, Robert. The First Jack the Ripper Victim Photographs. Edmonton: Zwerghaus,

2003.

MacFarlane, Dana. Photography at the Threshold: Atget, Benjamin and Surrealism.

History of Photography 34.1 (2010): 1728.

Novak, Daniel Akiva. Realism, Photography, and Nineteenth-Century Fiction. Cambridge:

Cambridge UP, 2008.

Pultz, John. The Body and the Lens: Photography 1839 to the Present. New York: Abrams, 1995.

Rosenblum, Naomi. A World History of Photography. New York: Abbeville Press, 1984.

Rugoff, Ralph. Scene of the Crime. Scene of the Crime. Ed. Rugoff. Cambridge: MIT P,

1997.

Salzani, Carlo. The City as Crime Scene: Walter Benjamin and the Traces of the Detective. New German Critique 100 (2007): 16587.

Walkowitz, Judith R. City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian

London. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992.

Wollen, Peter. Vectors of Melancholy. Scene of the Crime. Ed. Ralph Rugoff. Cambridge:

MIT P, 1997.

spring 2014

This content downloaded from 188.2.91.62 on Mon, 16 May 2016 15:41:52 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- You Are The Reason PDFDocument12 pagesYou Are The Reason PDFAutumn JMGPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- How It Feels To Be Colored Me, by Zora Neale HurstonDocument3 pagesHow It Feels To Be Colored Me, by Zora Neale HurstonIuliana Tomozei67% (9)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Footing Tie Beam Details: Left MID RightDocument1 pageFooting Tie Beam Details: Left MID RightLong Live TauPas encore d'évaluation

- Plywood ScooterDocument7 pagesPlywood ScooterJim100% (4)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Lista EurodanceDocument8 pagesLista EurodanceNelson van RoinujPas encore d'évaluation

- Middle Eastern ScaleDocument2 pagesMiddle Eastern ScaleRex MartinPas encore d'évaluation

- Jeff Foster QuotesDocument28 pagesJeff Foster Quotesznyingwa100% (2)

- SR20DET Engine Swap GuideDocument10 pagesSR20DET Engine Swap GuideJeff KentPas encore d'évaluation

- Ivy League VestDocument4 pagesIvy League VestNoémia100% (2)

- 2 XII Practical ManualDocument56 pages2 XII Practical ManualAnonymous OvW9H4ZDB4100% (1)

- John Goldsby The Jazz Bass Book For Contrabbasso B00D7IB0GKDocument2 pagesJohn Goldsby The Jazz Bass Book For Contrabbasso B00D7IB0GKCarlos Castro AldanaPas encore d'évaluation

- BentoniteDocument6 pagesBentoniteWahyu MycRyPas encore d'évaluation

- Proofs of A Conspiracy by John RobisonDocument239 pagesProofs of A Conspiracy by John Robisonhasangetinya100% (6)

- Chapter 4 Fashion CentersDocument48 pagesChapter 4 Fashion CentersJaswant Singh100% (1)

- Speech For English CarnivalDocument5 pagesSpeech For English CarnivalshammalabsreetharanPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Review - Doctrine of God by John FrameDocument3 pagesBook Review - Doctrine of God by John FrameJ. Daniel Spratlin100% (1)

- Planting A 1986 Oo WoDocument35 pagesPlanting A 1986 Oo WoGile BrankovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Frankfurtapmr PDFDocument12 pagesFrankfurtapmr PDFGile BrankovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Article Parfit - PersonalIdentity PDFDocument26 pagesArticle Parfit - PersonalIdentity PDFHoupa HoupaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Challenge of Cultural Relativism: James RachelsDocument14 pagesThe Challenge of Cultural Relativism: James RachelsGile BrankovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Moral Relativism in ContextDocument41 pagesMoral Relativism in ContextGile BrankovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Gettier Is Justified True Belief KnowledgeDocument3 pagesGettier Is Justified True Belief KnowledgeantoncamelPas encore d'évaluation

- Staging The Ethical in The State of Emer PDFDocument12 pagesStaging The Ethical in The State of Emer PDFGile BrankovicPas encore d'évaluation

- White Fine TuningDocument9 pagesWhite Fine TuningNasifkhanPas encore d'évaluation

- BoghossianDocument3 pagesBoghossianGile BrankovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Descartes Meditations1 PDFDocument4 pagesDescartes Meditations1 PDFAman RatanPas encore d'évaluation

- Victorianstudies.56.3.433 Fotografija PDFDocument10 pagesVictorianstudies.56.3.433 Fotografija PDFGile BrankovicPas encore d'évaluation

- HABIBIE AINUN, The Recent Less Love StoryDocument2 pagesHABIBIE AINUN, The Recent Less Love StoryCha DhichadherPas encore d'évaluation

- Gujarati Samaj Guest HousesDocument3 pagesGujarati Samaj Guest HousesjitmPas encore d'évaluation

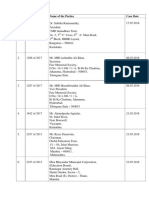

- S.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDDocument4 pagesS.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDAasim Ahmed ShaikhPas encore d'évaluation

- Mapeh 8 Prelim ExamDocument5 pagesMapeh 8 Prelim ExamRonald EscabalPas encore d'évaluation

- The Man Who Sold The WorldDocument9 pagesThe Man Who Sold The WorldJoell Rojas MendezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Satire in 'Gulliver's Travels'Document6 pagesThe Satire in 'Gulliver's Travels'Sarbojeet Poddar100% (1)

- The Image of Man - An Essay On ManDocument3 pagesThe Image of Man - An Essay On ManAna RtPas encore d'évaluation

- English Plus MIDTERM ExamDocument3 pagesEnglish Plus MIDTERM ExamRosanna Navarro100% (1)

- Work of ArchDocument5 pagesWork of ArchMadhu SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Aspie Quiz CorrectedDocument16 pagesAspie Quiz CorrectedKeplerPyePas encore d'évaluation

- The Buddhas Words at Cave Temples PDFDocument42 pagesThe Buddhas Words at Cave Temples PDFVarga GáborPas encore d'évaluation

- MetalDocument5 pagesMetalartemis2529Pas encore d'évaluation

- Always Looking Up - The Adventures of An Incurable Optimist - Michael J. Fox-VinyDocument75 pagesAlways Looking Up - The Adventures of An Incurable Optimist - Michael J. Fox-VinyFatima RafiquePas encore d'évaluation

- Barbeau, Maurius. Totem Poles (Vol. 2)Document25 pagesBarbeau, Maurius. Totem Poles (Vol. 2)IrvinPas encore d'évaluation