Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Picea Omorika PDF

Transféré par

Dragana Savić Lakić0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

12 vues1 pageTitre original

Picea_omorika.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

12 vues1 pagePicea Omorika PDF

Transféré par

Dragana Savić LakićDroits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 1

Picea omorika

Picea omorika in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats

D. Ballian, C. Ravazzi, G. Caudullo Threats and Diseases

Picea omorika (Pani) Purk., the Serbian spruce, is a living fossil tree restricted to a small area at the boundary of Serbia The current population decline is related to its inability to

and Bosnia Herzegovina. It grows in cool temperate mixed forests on mountain slopes but also withstands poorly aerated compete with other tree forest species12 . The small range of Serbian

soils. Poor regeneration, fire impact in the 19th century and forest tree competition together with climate warming in spruce, composed of isolated populations, and the occurrence of

recent years has left the Serbian spruce with the status of endangered species. Its prominent columnar habit and silvery self-fertility affect the genetic structure which is specific for each

sheen, together with tolerance to pollution, make it a valuable tree for urban landscapes. Frequency of the populations, given genetic drift and depression10, 22, 23.

< 25%

25% - 50%

However, other results show relatively high genetic variation, which

The Serbian spruce (Picea omorika (Pani) Purk.) is a slender 50% - 75% is characteristic for conifers24 . The biggest issue for Serbian spruce

tree up to 50m high and 1m in diameter, featured by a distinctive > 75%

is fires, which have reduced its spread during the last century7, 11, 25.

Chorology

narrow conical crown1 . Root systems are very shallow and branched. Native Another problem is a small number of fertile trees and poor natural

Second order branches are curved downward and adpressed to the regeneration, which may be even worsened by climate change10.

main trunk. This strictly monopodial spire-shape is only typical For this reason Serbian spruce now has the status of endangered

in clean and mixed forests, cultivated individuals in open spaces species12 . Currently there are no reliable data about insects and

becoming wide crowned. Like other spruces, young branchlets bear diseases which attack Serbian spruce, but there is some information

spirally-arranged swellings (pulvini) supporting the needles, but in about some of the pests which are attacking introduced samples in

Serbian spruce the first and second year branchlets are pubescent. North America. Some sources list aphids, mites, scale and budworm

Needles are 0.8-1.8cm long and 1.1 to 1.8mm wide2 , basally as potential insect problems; however so far there are no reports

truncated and horizontally compressed in two sides. Their lower of these pests significantly affecting the trees in Pennsylvania. The

surface has two prominent, white stomatal bands (epistomatic large pine weevil (Hylobius abietis L.) is among the most serious

setting) of 4-6 lines each, giving the tree a silvery sheen. Pollen pests affecting young coniferous forests in Europe26, 27, and Serbian

bears two wings, smaller than in Norway spruce (Picea abies)3; spruce partly coexists with the natural niche of this pest26 . The

pollen morphology and pollination mechanism are not yet fully Serbian spruce is susceptible to the bark beetles Ips typographus

pinpointed4 . Female cones are produced at the top of the crown5 . and Dendroctonus micans28-30. It is also vulnerable to Gremmeniella

They are first erect, then develop a pendulous, resinous, dark abietina28, 31 and may be subject to attacks by Pristiphora abietina28,

bluish-violet ovoid-oblong cone, reaching up to 6.5cm long once 30

. The white pine weevil (Pissodes strobi) also has the potential to

ripe, but often less than 3cm, thus resembling its Canadian relative seriously affect Serbian spruce if not controlled1 .

black spruce (Picea mariana) and even the conifers of genus Tsuga. Map 1: Plot distribution and simplified chorology map for Picea omorika.

Frequency of Picea omorika occurrences within the field observations as

A cone may contain up to 90, nearly spherical seed scales, each reported by the National Forest Inventories. The chorology of the native spatial

containing two wind-dispersed seeds. The old cones remain on the range for P. omorika is derived after Farjon andFiler, and Stevanovi et al.32, 33 .

tree for up to 2 years6 .

Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), alder (Alnus glutinosa) and other

Distribution broad-leaved also occur. The mesoclimate is oceanic, with

Serbian spruce is restricted to a small area along the Drina cold winter temperatures and heavy snow followed by hot dry

River at the boundary of Serbia and Bosnia Herzegovina, with a summers15, 16 . The tree regenerates quite well after catastrophic

total occurrence extent of only 4km2 7-10 . The main stands that fires, but suffers competition from broadleaves; thus only steep

grow in National parks in the Tara Mountains and an isolated slopes and limestone cliffs are successfully re-colonised17.

population in the Mileseva River canyon in Serbia are protected, Serbian spruce also withstands poorly aerated soils in peat bogs,

while in Bosnia and Herzegovina they are on its protected thanks to its ability to root in the upper layer, a common feature

habitats11 . Other isolated spots, each consisting of a few hundred in spruces which are stress avoiders of anoxia18 . This behaviour

individuals, occur between Viegrad, Rogatica and Srebrenica, also recalls its Early Pleistocene ancestors, growing in ancient

Dark bluish-violet female cones at the top of the crown.

and there are two isolated populations further south (ajnie and peatlands and recorded by in situ macrofossils19 . (Copyright Iifar, commons.wikimedia.org: PD)

Foa)10-12 . Palaeobotanical records show that this stenoendemic

pattern results from an overall reduction from a wide range Importance and Usage References

spanning most of Central Europe during cool and moist temperate Wood of Serbian spruce was valued as a technical wood [1] M. Vidakovic, Tree Physiology 12, 319 (1993). [17] P. Burschel, Forstarchiv 36, 113 (1965).

interstadials at the onset of the Last Glaciation, 100000 years because of its good quality. It was also used to make special [2] B. Radovanovi, J. inar Sekuli, T. Raki, [18] R. M. M. Crawford, Studies in plant

I. ivkovi, D. Lakui, Botanica Serbica 38, survival: ecological case histories of

ago13 . Serbian spruce survival in the Dinaric Alps during the Last kinds of pots for cheese1,20 . As a building material, its timber 237 (2014). plant adaptation to adversity (Blackwell

Scientific Publications, Oxford, 1989).

Glacial Maximum is supported by its current genetic structure was mostly used for roof constructions. Today only its aesthetic [3] H.-J. Beug, Leitfaden der

Pollenbestimmung fr Mitteleuropa und [19] v. Bek, Z. Kvaek, F. Hol, Late Pliocene

which retains ancient imprints6, 14 . features and tolerance to city pollution and to insect pests are angrenzende Gebiete (Verlag Dr. Friedrich palaeoenvironment and correlation of

Pfeil, 2004). the Vildtejn floristic complex within

of value21 . This is why people use it more than other conifers Central Europe (Academia Nakladatelstvi

Habitat and Ecology in cities with high levels of pollution. Serbian spruce deserves a

[4] C. J. Runions, K. H. Rensing, T. Takaso, J.

N. Owens, American journal of botany 86, Cesckoslovensk e Akademie Ved, Praha,

190 (1999). 1985).

The modern habitat of Serbian spruce is too limited for a more prominent place in commercial and residential landscapes. [20] G. Krssmann, Manual of Cultivated

[5] J. Jevti, umartsvo 13, 79 (1960).

straightforward evaluation of species tolerance limits. The main It can be used in groups, as a single specimen, or even as an [6] J. M. Aleksic, Genetic structure of natural

Conifers (Timber Press, Portland, 1985).

[21] W. Dallimore, A. B. Jackson, A Handbook

habitats occur on steep, east, north and west facing, often evergreen street tree. It has utility as a natural screen and populations of serbian spruce [picea

of Coniferae and Ginkgoaceae (Edward

omorika (pan.) purk.], Ph.D. thesis,

rocky slopes, mostly on limestone, but also on serpentine, at an selections with a narrow habit are suitable even for small urban University of Natural Resources and Arnold Ltd, London, 1961), third edn.

Applied Life Sciences, Vienna (2008). [22] H. Kuittinen, O. Savolainen, Heredity 68,

altitude of between 800 and 1500m. It may form the dominant landscapes. Serbian spruce represents a welcome alternative to 183 (1992).

[7] P. Fukarek, Godinjak Biolokog instituta

canopy in a closed forest together with Norway spruce (Picea the all-to-common Norway and Colorado spruce (Picea pungens). Univerziteta u Sarajevu 3, 141 (1951). [23] T. Geburek, Silvae genetica 35, 169

(1986).

abies) and black pine (Pinus nigra) at higher elevations, or with Today there are many cultivars of Serbian spruce produced in [8] P. Fukarek, Problems of Balkan flora

and vegetation: proceedings of the first [24] H. Kuittinen, O. Muona, K. Krkkinen,

beech (Fagus sylvatica) at lower ones, but silver fir (Abies alba), nursery gardens and grown in parks20 . International Symposium on Balkan Flora v. Borzan, Canadian Journal of Forest

and Vegetation, Varna, June 7-14, 1973, Research 21, 363 (1991).

D. Jordanov, ed. (Bulgarian Academy of [25] D. B. oli, Zatita prirode 33, 1 (1966).

Sciences, Sofia, 1975), pp. 146161.

[26] J. I. Barredo, et al., EPPO Bulletin 45, 273

[9] P. Fukarek, Hrvatski umarski List 2, 25 (2015).

(1941).

[27] CABI, Hylobius abietis (large pine weevil)

[10] D. Ballian, et al., Plant Systematics and (2015). Invasive Species Compendium.

Evolution 260, 53 (2006). http://www.cabi.org

[11] M. Toi, Akademija nauka i umjetnosti [28] D. de Rigo, et al., Scientific Topics Focus 2,

Bosne i Hercegovine 72, 267 (1983). mri10a15+ (2016).

[12] M. Mataruga, D. Isajev, M. Gardner, T. [29] R. Vujii, S. Budimir, Somatic

Christian, P. Thomas, The IUCN Red List of Embryogenesis in Woody Plants, S. M. Jain,

Threatened Species (2011), pp. 30313/0+. P. K. Gupta, R. J. Newton, eds. (Springer

[13] C. Ravazzi, Review of Palaeobotany and Netherlands, 1995), vol. 44-46 of Forestry

Palynology 120, 131 (2002). Sciences, pp. 8197.

[14] J. Aleksi, T. Geburek, Plant Systematics [30] D. Doom, Nederlands bosbouw tijdschrift

and Evolution 285, 1 (2010). 46, 79 (1974).

[15] V. Stefanovi, V. Beus, v. Burlica, H. [31] I. M. Thomsen, Forest Pathology 39, 56

Dizdarevi, I. Vukorep, Ekoloko- (2009).

vegetacijska rejonizacija Bosne i [32] A. Farjon, D. Filer, An Atlas of the Worlds

Hercegovine, Posebna izdanja br. 17 Conifers: An Analysis of their Distribution,

(umarski fakultet Univerziteta u Biogeography, Diversity and Conservation

Sarajevu, Sarajevo, 1983). Status (Brill, 2013).

[16] M. Jankovi, N. Panti, V. Mii, N. Dikli, M. [33] V. Stevanovi, et al., Botanica Serbica 38,

Gaji, Vegetacija SR Srbije, vol. 1 (SANU 251 (2014).

Odeljenje prirodno-matematikih nauka,

Beograd, 1984).

This is an extended summary of the chapter. The full version of

this chapter (revised and peer-reviewed) will be published online at

https://w3id.org/mtv/FISE-Comm/v01/e0157f9. The purpose of this

summary is to provide an accessible dissemination of the related

main topics.

This QR code points to the full online version, where the most

updated content may be freely accessed.

Please, cite as:

Ballian, D., Ravazzi, C., Caudullo, G., 2016. Picea omorika in Europe:

Serbian spruce in Bosnia Herzegovina where it codominates a mixed forest with several broadleaves. distribution, habitat, usage and threats. In: San-Miguel-Ayanz,

(Copyright Dalibor Ballian: CC-BY) J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A. (Eds.),

European Atlas of Forest Tree Species. Publ. Off. EU, Luxembourg,

pp. e0157f9+

Tree species | European Atlas of Forest Tree Species 117

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- 09 - Chapter 1Document4 pages09 - Chapter 1Aftab HusainPas encore d'évaluation

- UK Carbon Lookup GidanceDocument19 pagesUK Carbon Lookup GidancePanna R SiyagPas encore d'évaluation

- #Hardwood and Softwood Hardwood: HARDWOOD Is Wood From Dicot Trees. These AreDocument6 pages#Hardwood and Softwood Hardwood: HARDWOOD Is Wood From Dicot Trees. These Areharsh wardhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Spring tree and shrub offer from Periland NurseryDocument13 pagesSpring tree and shrub offer from Periland NurseryCuravalea Nicolae Si ElenaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 - g8 - The Wonderful Pear TreeDocument8 pages2 - g8 - The Wonderful Pear Treejustinbasic100% (2)

- Tree GrowingDocument2 pagesTree Growinglink2u_007Pas encore d'évaluation

- Broom Style Bonsai GuideDocument5 pagesBroom Style Bonsai GuidePolyvios PapadimitropoulosPas encore d'évaluation

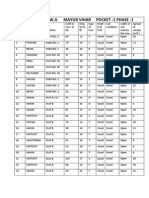

- Tree+Census+RWA+MAYUR+VIHAR+POCKET-1+PH +1Document13 pagesTree+Census+RWA+MAYUR+VIHAR+POCKET-1+PH +1Amit KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Supw ProjectDocument9 pagesSupw ProjectSiddharth Katoch100% (1)

- Hard and Soft Woods: Monocot WoodDocument1 pageHard and Soft Woods: Monocot WoodDissasekaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Descriptions of The 16 Major Forest Type-Groups According To Champion and Seth (1968)Document4 pagesDescriptions of The 16 Major Forest Type-Groups According To Champion and Seth (1968)RajKumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Privet Bonsai Carving 3 Trunks Into 1Document4 pagesPrivet Bonsai Carving 3 Trunks Into 1Dheanx InteristaPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Trim A Coral TreeDocument4 pagesHow To Trim A Coral TreeEzzie DoroPas encore d'évaluation

- Teco 1Document297 pagesTeco 1Rizal FebriantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Brown's Telugu - English DictionaryDocument1 pageBrown's Telugu - English DictionarybadaboyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ficus Species Tree List Ornamental PDF UkDocument2 pagesFicus Species Tree List Ornamental PDF UkKiaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Cherry Blossom FestivalDocument4 pagesCherry Blossom FestivalNonoy GuiribsPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Fruit Bearing Trees Found in The Philippines PDFDocument1 pageList of Fruit Bearing Trees Found in The Philippines PDFMon Kiego MagnoPas encore d'évaluation

- Donar's Oak: "Bonifacius" (1905) by Emil DoeplerDocument5 pagesDonar's Oak: "Bonifacius" (1905) by Emil DoeplerCarl Ritchie TemplePas encore d'évaluation

- Top 50 Fruit Trees in the PhilippinesDocument1 pageTop 50 Fruit Trees in the PhilippinesAmberValentine100% (1)

- Arbustedas Termófilas Mediterráneas (Asparago-Rhamnion)Document7 pagesArbustedas Termófilas Mediterráneas (Asparago-Rhamnion)DavidPas encore d'évaluation

- Pending Work As of May 2017Document1 pagePending Work As of May 2017Shivaram SuppiahPas encore d'évaluation

- High End Wood For PensDocument2 pagesHigh End Wood For PensInform7105Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bus 61 and 63 ScheduleDocument11 pagesBus 61 and 63 ScheduleMuhammad Akbar WalennaPas encore d'évaluation

- # Abbr Botanical Name Common Name Reference Image Qty Unit TreeDocument14 pages# Abbr Botanical Name Common Name Reference Image Qty Unit TreeUTTAL RAY100% (1)

- DeKalb County Tree Protection - MunicodeDocument33 pagesDeKalb County Tree Protection - MunicodeBrookhaven PostPas encore d'évaluation

- Scientific NameName of TreeDocument6 pagesScientific NameName of Treenestor donesPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 2: Math 4 Unit 1Document16 pagesLesson 2: Math 4 Unit 1Zaimin Yaz MarchessaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Survey of Albanian Tree and Shrub Names - Robert ElsieDocument37 pagesA Survey of Albanian Tree and Shrub Names - Robert ElsieajegeniPas encore d'évaluation

- Vegetation IndiaDocument5 pagesVegetation IndiaKedar BhasmePas encore d'évaluation