Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Critical Success Factors For International Projects

Transféré par

zaki_abdrahmanTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Critical Success Factors For International Projects

Transféré par

zaki_abdrahmanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Critical Success Factors for International Projects

Sue Freedman, Ph.D. and Lothar Katz

The future of project management involves an ever increasing number of projects that

require the cooperation of geographically and culturally diverse teams. Leaders in the

international project arena today are more aware of the challenges and more excited by

the opportunities to work with international teams and partners.

As experience with these international project partnerships grows, the organizational

competencies needed for success are emerging. Most prominent among them are the

knowledge and skill to select the right projects and the right project partners for

international efforts, as well as the ability to select, develop, and support leaders for

projects and programs who have the skills and flexibility to make cross-border

collaboration successful.

The Challenges of Working in an International Project Environment

As corporations all over the world have found time and time again, international project

success requires mastering numerous challenges in a complex context. Conducting

projects in different countries, with their unique legal and political environment, security

issues, economic factors, and infrastructure limitations and requirements, increases

complexity far beyond that of projects executed in domestic settings. In addition, the

geographic distances, language barriers, and cross-cultural gaps that are typical of an

international project environment introduce further leadership challenges and additional

risk. Consider the following example:

A high-technology company has assigned an experienced project manager to

initiate, plan, and execute a project to develop and manufacture a complex new

electronic product. A formal selection process named a major manufacturing

company in Bratislava, Slovakia as the best production facility for the product.

This manufacturer combines the necessary experience and competence with a

significant cost advantage over competing vendors. The products hardware

design will be done in the US, while the development of the complex system

software will mostly take place in a wholly-owned company subsidiary in

Bangalore, India. The Slovakian manufacturer has assigned a number of test and

production specialists as members of the project team.

Being under a tight timeline, the project receives much attention from the

technology companys senior management. Nevertheless, a number of issues start

surfacing as the project moves through the planning and execution phases.

Among them are the discovery that the manufacturers quality systems do not

meet the projects requirements, high staff turnover rates in Bratislava that make

it difficult to build and maintain the required know-how, changing labor

regulations by Slovakian government agencies that lead to significant cost

overruns, as well as frequent misunderstandings between the engineering teams

Sue Freedman and Lothar Katz 1

www.managingprojectsacrossborders.com

in the US, Slovakia, and India. Making matters worse, Slovakian management,

upon learning that the software team in India encountered a delay of several

weeks, temporarily reassign key people to other tasks. The project manager does

his best to get all tasks back on schedule, but with limited success. The first

production prototypes from Bratislava end up being two months late and failing

several critical tests.

After further attempts to get the project back on track failed, it becomes clear that

the product would miss its market opportunity. The companys senior

management decides to stop the project and terminate the contract with the

manufacturer in Bratislava, who subsequently brings up a legal case in a

Slovakian court.

Clearly, this international product development project was troubled by a number of the

before mentioned factors. For most projects, it would be impossible to pinpoint any one

such factor as the sole root cause for the projects struggle or failure. Taken in isolation,

each of them represents a task an experienced project manager might find challenging but

nonetheless manageable. Collectively, however, these factors elevate international

projects to higher degrees of overall risk and greater complexity than domestic projects

with similar technical scope.

Three factors are most prominent in determining the success of international projects:

Selecting the right projects

Selecting the right partners

Providing effective project leadership

Selecting International Projects and Partners

When making decisions about cross-border projects and partners, such as outsourcing

vendors, suppliers, manufacturers, development houses, or venture partners, it is

important to consider all relevant legal, political, security, economic, infrastructure, and

cultural factors.

Cultural aspects are often overlooked or receive inadequate consideration. For example,

orientations towards risk and time may have a substantial impact on the planning and

execution of international projects. Assigning a high-risk project to a team whose

members belong to a somewhat risk-averse culture, such as Japan, China, or Germany,

often leads to disappointing results: team members may spend excessive time planning

unpredictable tasks, attempt to reduce risks by changing performance aspects, or waste

energy on coming up for reasons why it wont work instead of focusing on how to

make the project successful. Similarly, executing time-critical projects in cultures where

being patient and accepting fate are crucial values, for instance in Indonesia, Thailand, or

certain African countries, presents a poor cultural fit that will likely cause friction, as

does sharing critical knowledge with partners in countries like China that lack a strong

culture of IP protection. It is therefore vital to review such cultural characteristics in the

context of a projects priorities, considering alternatives where appropriate.

Sue Freedman and Lothar Katz 2

www.managingprojectsacrossborders.com

Another challenge lies in the approach to selecting international partners. It is never

sufficient to verify that a targeted partner has the required competencies. Inherently,

companies are characterized by their key values, goals, and objectives. When partnering

with others, these factors are rarely fully aligned between domestic business partners, let

alone those working across borders and cultures.

Successful partnering requires sufficiently aligning goals & objectives on both sides.

Reaching similar alignment over the partners values, however, may be hard or even

impossible, especially when working across cultures. Though the collaboration will be

easier if both sides value sets are well aligned, the existence of value gaps per se is not a

reason to abandon a partnership. However, it is crucial to identify and mutually

acknowledge value differences in such a project partnership.

For the above reasons, the process of selecting international partners needs to include a

clear definition of goals and objectives for the partnership. It must start with a candid

assessment of the values, stated and unstated, of the company seeking an international

partnership. Once potential partners have been identified, the next step will be to clarify

and align competencies, intentions, and expectations on both sides. As part of their due

diligence process, both potential partners will be well advised to verify and confirm all of

the information they are given. Lastly, the potential partners must analyze differences

between their respective values that might affect their collaboration and decide how to

deal with them.

Asking the following six questions can be helpful when starting the process of picking

international projects and partners:

1. How complex is the project?

2. How complex is the project infrastructure?

3. What are the key risks areas of the project?

4. How time-critical is the project?

5. What are your long-term objectives?

6. Which cultural barriers will you have to address?

Of these, the first four relate to risk management and help in deciding which projects to

take international and which partners/cultures to work with. The final two questions serve

as guidance for the analysis of value differences between the partners that could affect a

projects success if not properly addressed.

Leading Across Cultures

Working with different cultures places new challenges on those leading the projects and

those who lead the organizations selecting and sponsoring those projects. Cultures have

differing expectations of leaders, different rules about business relationships, and

differing rule sets around ways of work. A look at the following example illustrates some

of these differences:

A team in Hyderabad, India, is responsible for creating a tool for an internal

customer of a US company. Four weeks into the project, the US team lead comes to

Sue Freedman and Lothar Katz 3

www.managingprojectsacrossborders.com

the project manager complaining that India is making the tool too complex and

causing delays. The project manager picks up the phone and calls the Indian team

member working most closely with the US lead. He explains, politely but clearly, that

the Indian team is to develop the tool exactly as requested. The team member in

Hyderabad is very gracious. He assures the project manager that there will be no

problem. The Project manager hangs up the phone, satisfied that the problem is

solved, and moves on to his next action item.

Two weeks later, the US team lead is back in the project managers office, explaining

that she is getting no response from India at all, even though she has called and

emailed a number of times. She is frustrated and discouraged. She voices her opinion

that this whole international project partnership idea is a bad one, because these

people cant be trusted.

This example illustrates how routine project issues escalate into real problems in

international settings. The US project manager dealt with his Indian project team member

in a way that undoubtedly works with US project members. In doing so, he ignored

highly relevant cultural differences between India and the US. He insulted the team

members supervisor by going directly to his subordinate. He put the team member in the

difficult position of speaking for both his boss and his team mates with no opportunity to

consult them. By being so direct, the project manager assured an affirmative answer from

the team member and missed any small opportunity he may have had to get reliable

information about the problem.

India is an authoritarian, group-oriented culture that often uses indirect communication.

The US, on the other hand, is more egalitarian, more individualistic, and much more

direct in its communication. These differences mean that communication is very often

confusing for both sides. If the confusion gets too great, work and communication simply

stop.

To solve this particular problem, the best course for the US project manager is to pick up

the phone and call the manager to whom the Indian team reports. He needs to apologize,

acknowledging that he should have discussed the issue first with the manager. He needs

to listen and then work with the manager to find a solution to which they are both

comfortable. Finally, he needs to spend some time working with his US team lead,

explaining cultural differences and the strategies that work best in adapting to them.

Challenges in Leading Across Cultures

As illustrated above, the challenges a project leader at any level faces in leading across

cultures are significant. In addition to altering behaviors to accommodate the different

expectations of leaders, he or she must recognize and adapt to differences in decision

making and work styles, adjust to differences in influence and negotiation rules/tactics,

and deal with the communication challenges that accompany language differences and

separation by distance and time zones.

Project leadership is the responsibility of the project manager. Leadership can be defined

as the ability of an individual to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute

Sue Freedman and Lothar Katz 4

www.managingprojectsacrossborders.com

toward the effectiveness and success of the organization (House et.al., 1999). Thinking

of leadership in this way helps clarify why it is so important for the international project

leader to adapt his or her behavior to the expectations and values of the culture of his or

her foreign colleagues. Most cultures value authoritarian leadership more than the US

does. People in these cultures expect the leader to be more autocratic and directive.

Leaders who are too familiar, too casual, or just too friendly with subordinates generate

distrust and confusion. On the other hand, there are cultures whose members expect their

leaders to be more egalitarian than in the US and will resent and often ignore the leader

who acts as if he or she is in any way superior to them. They expect their leaders to

consult with them and to treat them as equals. This means that it is entirely possible to

behave in a way that will be viewed as weak and ineffective in one culture and viewed as

boorish and ineffective in another. Cultures who value more authoritarian leadership

include almost all countries south of the US, as well as Russia, China, India, and most of

the Mid and Far East. Cultures that value more egalitarian styles include Scandinavia,

Israel, Australia, and New Zealand. The US is more egalitarian than most other cultures,

but not as much as those listed in the previous sentence.

In addition to these adaptation issues, leaders of international projects face significant

development issues, as international work at the project level is still new territory for

everyone involved. Even those with many years of experience report they are still

learning how to best understand and communicate with their international colleagues.

Project leaders at all levels, as well as project team members, have to both learn, and

teach everyone involved, new ways of working together.

Among the most challenging people to work with on an international project are

superiors who are unaware of differences in leading across cultures. These people often

miscommunicate, misunderstand, and misinterpret the behaviors and intentions of their

colleagues. At the upper levels of the organization, this can be particularly difficult for

the project manager. Below is a list of behaviors typical of an uninformed and unhelpful

supervisor of an international project manager:

Delegates completely, doesnt see any reason to get involved.

They work for usyou make that clear to them!

Asks if the project manager is keeping bankers hours when he/she comes in

late after being on the phone from 11-3 the night before.

Sees no reason to be selective (except technically) in placing people on an

international project.

Selects high risk/high collaboration projects for international work.

Assumes the time required is the same for international and domestic projects

Is unwilling or unable to change leadership style to meet cultural expectations.

The behaviors are indicative of a leader who simply does not understand the realities of

an international project. In this situation, the project manager has the added burden of

educating his or her boss on the realities of international project work. This is perhaps

another reason for selecting project managers who are very skilled at influencing,

negotiating, and adapting their behavior to different people and contexts.

Sue Freedman and Lothar Katz 5

www.managingprojectsacrossborders.com

Ideally, the project managers supervisor is aware of the challenges of international

projects and is able to provide support and advice to the project manager. In addition, that

ideal supervisor will have close relationships with his counterparts in partnering

organizations and can use his influence when necessary to resolve issues or expedite

solutions.

There are also project managers who should not be assigned to international projects,

even when they are very successful in their own cultures. Below is a list of the behaviors

or perspectives that make a project manager most likely to fail in an international project:

Doesnt work to build relationships.

Insults or ignores foreign subordinate managers (often unknowingly).

Spends little or no time in designing/building communication systems.

Always supports the US side in conflicts.

Talks very fast and very loud

Expects all the adapting to be done by foreign colleagues

Attributes problems to laziness or stupidity (and shows it).

Refuses to change his/her behavior to accommodate differences

Doesnt follow up to insure that agreements are understood and executed.

Assume there is agreement on rules around time and quality.

This list characterizes a project manager who is uninformed about the impact of cultural

differences on international projects. One of the most common complaints from

experienced international professionals is about the number of people sent to work with

or for them who are and remain unaware of the very real impact of culture and language

on the way in which a project must be managed. An emerging best practice is to assure

that adequate training in cultural differences is provided to all those managing or working

on international projects. In addition, it is best to select those project leaders who have

significant relationship building skills and are well aware of the role relationships play in

international project success.

Summary

Projects that cross borders offer unique opportunities and significant risk. Best practices

that mitigate some, although certainly not all, of that risk are available. These include

disciplined project and partner selection practices that weigh legal, political, security,

economic, infrastructure, and cultural factors. Also critical is the careful alignment of the

goals and objectives of all participating parties.

Careful selection and alignment, however, are not enough. Organizations that excel in

international project management must select, train and support project leaders at all

levels flexible enough to adapt to significant cultural differences, and deliberate enough

to manage the systems and structures that assure adequate and timely communication and

adherence to strict quality standards. Leaders who possess those unique set of talents are

rare, but their numbers are growing.

Sue Freedman and Lothar Katz 6

www.managingprojectsacrossborders.com

Sue Freedman, Ph.D. and Lothar Katz are the creators and primary instructors of Managing

Projects Across BordersTM, a series of three workshops on Leading International Projects and

International Project Organizations. Managing International Projects and Negotiating and

Working with International Customers, Suppliers and Other Partners are offered as public

workshops through the University of Texas at Dallas Project Management Program. Initiating

International Projects and Executing International Projects are offered as online classes.

Leading International Project Organizations is currently taught only as an in-house offering.

For information on these workshops, visit ManagingProjectsAcrossBorders.com. Sue and

Lothar also teach in the Executive Education Project Management MBA Program at the

University of Texas at Dallas.

Sue specializes in the people and organizational aspects of projects and project based

organizations. She spent 12 years with Texas Instruments, serving as Manager of

Organizational Effectiveness at the Division and Corporate level and 2 years as Vice-President

of Organizational Development and Human Resources in a large real estate investment trust.

She is a co-author of Beyond Teams: Building the Collaboration Organization (Jossey-Bass,

2003) and author of Managing Virtual Teams that Cross Borders in The Handbook on

Virtual Teams (Jossey Bass, 2008). Sue is a frequent presenter/trainer at professional

conferences, and through Webinars and in house training programs.

Lothar specializes in several aspects of international business. He is a former Vice President

and General Manager with Texas Instruments. During his 18-year corporate career, Lothar

managed large distributed product development organizations across the U.S., Germany, India,

China, Japan, and Australia. His extensive interactions with employees, customers, outsourcing

partners, and third parties in more than 25 countries around the world included many parts of

Asia. Originally from Germany, he has lived and worked both in the United States and in

Europe. Lothar also serves as a Business Leadership Center instructor at Southern Methodist

Universitys Cox School of Business and is the author of Negotiating International Business

The Negotiators Reference Guide to 50 Countries around the World (BookSurge, 2nd edition

2007).

Contact Sue and Lothar at sue_and_lothar@managingprojectsacrossborders.com

Sue Freedman and Lothar Katz 7

www.managingprojectsacrossborders.com

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- 6802988C45 ADocument26 pages6802988C45 AJose Luis Pardo FigueroaPas encore d'évaluation

- Documents - The New Ostpolitik and German-German Relations: Permanent LegationsDocument5 pagesDocuments - The New Ostpolitik and German-German Relations: Permanent LegationsKhairun Nisa JPas encore d'évaluation

- New Microsoft Office Power Point PresentationDocument21 pagesNew Microsoft Office Power Point PresentationSai DhanushPas encore d'évaluation

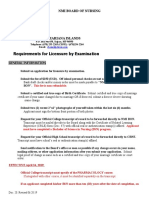

- 20 and 21. Requirements For Licensure by Examination Nclex. Revised 06.20.19 1Document2 pages20 and 21. Requirements For Licensure by Examination Nclex. Revised 06.20.19 1Glennah Marie Avenido RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- A330-200 CommunicationsDocument42 pagesA330-200 CommunicationsTarik BenzinebPas encore d'évaluation

- Cobit 2019 Design Toolkit With Description - Group x.20201130165617871Document46 pagesCobit 2019 Design Toolkit With Description - Group x.20201130165617871Izha Mahendra75% (4)

- Guide To Linux+ (2 Edition) ISBN 0-619-21621-2 End of Chapter Solutions Chapter 4 SolutionsDocument8 pagesGuide To Linux+ (2 Edition) ISBN 0-619-21621-2 End of Chapter Solutions Chapter 4 SolutionsNorhasimaSulaimanPas encore d'évaluation

- Training BookletDocument20 pagesTraining BookletMohamedAliJlidiPas encore d'évaluation

- 9500MPR - MEF8 Circuit Emulation ServicesDocument5 pages9500MPR - MEF8 Circuit Emulation ServicesedderjpPas encore d'évaluation

- ERP and SCM Systems Integration: The Case of A Valve Manufacturer in ChinaDocument9 pagesERP and SCM Systems Integration: The Case of A Valve Manufacturer in ChinaiacikgozPas encore d'évaluation

- BS EN 12536-2000 Gas Welding Creep Resistant, Non-Alloy and Fine Grain PDFDocument11 pagesBS EN 12536-2000 Gas Welding Creep Resistant, Non-Alloy and Fine Grain PDFo_l_0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Coomaraswamy, SarpabandhaDocument3 pagesCoomaraswamy, SarpabandhakamakarmaPas encore d'évaluation

- C3691 - NEC, NPN Transistor, 100v, 7v Base, 5A, High Switching SpeedDocument3 pagesC3691 - NEC, NPN Transistor, 100v, 7v Base, 5A, High Switching SpeedLangllyPas encore d'évaluation

- Nessus 6.3 Installation GuideDocument109 pagesNessus 6.3 Installation GuideminardmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Mathematical Description of OFDMDocument8 pagesMathematical Description of OFDMthegioiphang_1604Pas encore d'évaluation

- Long+term+storage+procedure 1151enDocument2 pagesLong+term+storage+procedure 1151enmohamadhakim.19789100% (1)

- 09931374A Clarus 690 User's GuideDocument244 pages09931374A Clarus 690 User's GuideLuz Idalia Ibarra Rodriguez0% (1)

- Animal and Human Brain Work With Treatment Its Malfunction: Pijush Kanti BhattacharjeeDocument6 pagesAnimal and Human Brain Work With Treatment Its Malfunction: Pijush Kanti BhattacharjeeNilakshi Paul SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- CS 201 1 PDFDocument7 pagesCS 201 1 PDFMd AtharPas encore d'évaluation

- Version 2 Production Area Ground Floor + 1st Floor Samil EgyptDocument1 pageVersion 2 Production Area Ground Floor + 1st Floor Samil EgyptAbdulazeez Omer AlmadehPas encore d'évaluation

- (EngineeringEBookspdf) Failure Investigation of Bolier PDFDocument448 pages(EngineeringEBookspdf) Failure Investigation of Bolier PDFcarlos83% (6)

- DD The Superior College Lahore: Bscs 5CDocument15 pagesDD The Superior College Lahore: Bscs 5CLukePas encore d'évaluation

- Relationship Between Organisations and Information SystemsDocument16 pagesRelationship Between Organisations and Information SystemsJoan KuriaPas encore d'évaluation

- 晴天木塑目录册Document18 pages晴天木塑目录册contaeduPas encore d'évaluation

- Gym Mega ForceDocument3 pagesGym Mega ForceAnonymous iKb87OIPas encore d'évaluation

- Remote SensingDocument30 pagesRemote SensingAdeel AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- 11kv BB1Document1 page11kv BB1Hammadiqbal12Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fault and Alarm Indicators: Planning and Installation Guide For Trident v2 SystemsDocument27 pagesFault and Alarm Indicators: Planning and Installation Guide For Trident v2 SystemsDeepikaPas encore d'évaluation

- MGT104 Assignment 3Document11 pagesMGT104 Assignment 3Lê Hữu Nam0% (1)

- Advanced English Communication Skills LaDocument5 pagesAdvanced English Communication Skills LaMadjid MouffokiPas encore d'évaluation