Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Technology Article 1

Transféré par

api-302210367Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Technology Article 1

Transféré par

api-302210367Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Creating Technology-Enhanced, Learner-Centered Classrooms:

K12 Teachers Beliefs, Perceptions, Barriers, and Support Needs

Yun-Jo An Charles Reigeluth

University of West Georgia Indiana University

Abstract

Although a wealth of literature dis- The learner-centered model focuses of the meta-analytical research on the

cusses the factors that affect technol- on developing real-life skills, such as effectiveness of problem-based learn-

ogy integration in general and how collaboration, higher-order thinking, ing (PBL), one of the learner-centered

to improve professional development and problem-solving skills, and better approaches. Their results indicate that

efforts, few studies have examined is- meets the complex needs of the informa- PBL is significantly more effective than

sues related to learner-centered tech- tion age. The learner-centered model traditional instruction when it comes to

nology integration. Thus, this study also addresses the personal domain, long-term knowledge retention, perfor-

aims to explore K12 teachers be- which is often ignored in conventional mance improvement, and satisfaction of

liefs, perceptions, barriers, and sup- schools and classrooms, and it results in students and teachers, whereas tradi-

port needs in the context of creating increased student motivation and learn- tional approaches are more effective for

technology-enhanced, learner-cen- ing. In learner-centered classrooms, stu- short-term retention. These are just a few

tered classrooms. The researcher used dents feel accepted and supported, feel examples. Numerous studies provide evi-

an online survey to collect data, and ownership over their learning, and are dence that students are motivated to learn

126 teachers participated in the sur- more likely to be involved and willing to and develop more in-depth understand-

vey. The findings of this study provide learn (Bransford et al. 2000; Cornelius- ing of content as well as real-world skills

practical insights into how to support White & Harbaugh, 2009; McCombs & in learner-centered environments.

teachers in creating technology-en- Whisler, 1997; Reigeluth, 1994). Todays students, often called digital

hanced, learner-centered classrooms. Research evidence on the effective- natives or the Net Generation, grow up

This article discusses the implica- ness of learner-centered approaches con- with technology. Most of them have nev-

tions for professional development tinues to grow. Recently, Cheang (2009) er known life without the Internet. They

and the need for paradigm change. examined the effects of learner-centered have spent their entire lives using com-

(Keywords: Learner-centered instruc- teaching on motivation and learning puters, cell phones, and other digital me-

tion, technology integration, teacher strategies in a third-year pharmaco- dia and have integrated technology into

beliefs, perceptions, barriers, support therapy course in a doctor of pharmacy almost everything they do. It is obvious

needs, teacher education, professional program. In the study, the students that technology is an integral part of their

development, paradigm change) were asked to complete the Motivated lives (Oblinger, 2008; Prensky, 2007). To

Strategies for Learning Questionnaire engage them in learning, there has been

(MSLQ) before and after taking the increased emphasis on the integration

O

ur information society needs course. Students also assessed the extent of technology into K12 classrooms.

people who can effectively to which the learner-centered approach Although a wealth of literature discusses

manage and use ever-increasing facilitated their learning. Results show technology integration in general, there

amounts of information to solve com- that students intrinsic goal orientation, is a lack of research on learner-centered

plex problems and to make decisions control of learning beliefs, self-efficacy, technology integration. This study aims

in the face of uncertainty. There is little critical thinking, and metacognitive to explore K12 teachers beliefs, percep-

argument that the traditional factory self-regulation significantly improved tions, barriers, and support needs in the

model of education is incompatible after taking the course. Students were context of creating technology-enhanced,

with the evolving demands of the in- also positive in their assessment of learner-centered classrooms.

formation age (Reigeluth, 1999b). The the learner-centered experience in the

factory model also does not take into course. These results indicate that the Learner-Centered Classrooms

account students varying needs, which learner-centered approach is effective in The American Psychological Association

leads to student dissatisfaction and de- promoting several domains of motiva- (1993, 1997) identified 12 learner-centered

motivation. Students and parents often tion and learning strategies. psychological principles. The domains of

perceive school learning as irrelevant to Using a qualitative metasynthesis ap- the learner-centered principlesthe meta-

their personal and real-life needs and proach, Strobel and van Barneveld (2009) cognitive and cognitive, affective, personal

interests. compared and contrasted the findings and social, developmental, and individual

54 | Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education | Volume 28 Number 2

Copyright 201112, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.3777 (Intl), iste@iste.org, iste.org. All rights reserved.

Learner-Centered Technology Integration

differences factorsemphasize both the Collaborative and authentic learning three main components: content, peda-

learner and learning. McCombs and experiences. Learner-centered teachers gogy, and technology. However, TPACK

Whisler (1997) contend that the learner- provide students with authentic learning goes beyond these three components.

centered perspective focuses equally on experiences that help students develop Emphasizing the importance of dynamic

the learner and learning and that the real-world skills, such as communication, relationships among these components,

ultimate goal of education is to foster the collaboration, critical-thinking, creative- Mishra and Koehler (2006, 2008) iden-

learning of all learners (p. 14). Learner- thinking, problem-solving, and decision- tified pedagogical content knowledge

centered instruction (LCI) does not take making skills. Students are encouraged to (PCK), technological content knowledge

only one form, but learner-centered work collaboratively with others, to solve (TCK), technological pedagogical knowl-

classrooms tend to have the following problems, and to create new knowl- edge (TPK), and technological pedagogi-

general characteristics in common: edge rather than just recall or restate cal content knowledge (TPCK) in addition

knowledge. Learning activities are often to content knowledge (CP), pedagogical

Personalized and customized learn- global, interdisciplinary, and integrated knowledge (PK), and technological knowl-

ing. Learner-centered teachers have (Bransford et al., 2000; Cornelius-White edge (TK). The TPACK framework shows

high expectations for all students and & Harbaugh, 2009; McCombs & Whisler, that technology integration requires much

pay close attention to the knowledge, 1997; Reigeluth, 1994). more than technical skills.

skills, and attitudes that each student Assessment for learning. Learner-cen- Recognizing the importance of the

brings into the classroom. Considering tered teachers assess different students links among technology, pedagogy, and

the unique and diverse needs and styles differently. They conduct assessments content, researchers have examined

of the students, they include person- not just to generate grades but to pro- ways to improve technology integration

ally meaningful and relevant goals and mote learning. They monitor individual practices and professional development

provide personalized learning experi- students progress continually to provide efforts. For instance, Ertmer et al. (2003)

ence and support. They are also sensitive feedback on their growth and progress. designed and implemented professional

to cultural issues as well as individual They also promote students reflection development activities to help teachers

differences. Students actively engage in on their growth as learners and help create problem-based learning environ-

learning and work at their own individ- them develop self- and peer-assessment ments that promote meaningful uses of

ual pace (Bransford et al., 2000; DiMar- skills. What they assess is congruent technology within the learner-centered

tino, Clark, & Wolk, 2003; McCombs & with students learning goals. Teachers context. Brush and Saye (2009) provided

Whisler, 1997; Reigeluth, 1994, 1999a; make all assessments as authentic as preservice social studies teachers with

Reigeluth & Duffy, 2008). possible (Bransford et al., 2000; Mc- opportunities to explore innovative,

Social and emotional support. Learner- Combs & Whisler, 1997; Weimer, 2002). emerging technologies in authentic social

centered teachers foster students social It is worth noting that different learn- studies learning and teaching situations.

and emotional growth as well as intel- er-centered teachers have varying but Kopcha (2010) presented a systems-

lectual growth by creating a supportive overlapping beliefs and that any single based model of technology integration

and positive environment. They assume learner-centered instruction will not that uses mentoring and communities of

that all students want to learn and necessarily include all of these attributes practice to prepare teachers to integrate

provide them with emotional support (McCombs & Whisler, 1997). technology in more student-centered

and encouragement. Students feel like ways. Polly and Hannafin (2010) pro-

they belong in the class (McCombs & Technology Integration posed a Learner-Centered Professional

Whisler, 1997; Reigeluth, 1999a). Although there is no clear definition of Development (LCPD) framework, which

Self-regulation. Learner-centered technology integration in K12 contexts includes six major features. LCPD efforts

teachers serve as facilitators rather than (Bebell, Russell, & ODwyer, 2004), tech- are (a) focused on student learning, (b)

transmitters of knowledge. They give nology integration is generally viewed teacher-owned, (c) intended to develop

students increasing responsibility for the as the use of technology for instruc- knowledge of content and pedagogies,

learning process and provide an optimal tional purposes. Mishra and Koehler (d) collaborative, (e) ongoing, and (f)

amount of structure without being over- (2006, 2008) introduced Technological, reflective. Overall, research suggests that

ly directive. They encourage students Pedagogical, and Content Knowledge professional development efforts move

participation and empower students by (TPACK) as a framework for teacher their focus from building teachers iso-

sharing power. They also help students knowledge for technology integration lated technical skills to preparing teachers

develop metacognitive skills and learn- and argued that the development of to implement technology-enhanced,

ing strategies. Students are actively TPACK is critical for effective technol- learner-centered instruction.

engaged in and take ownership of their ogy integration. The TPACK framework Despite generally improved conditions

learning (Cornelius-White & Harbaugh, builds on Shulmans (1986, 1987) idea of for technology integration, including in-

2009; McCombs & Whisler, 1997; Reige- pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). creased access to technology and increased

luth, 1994, 1999a; Weimer, 2002). As the name suggests, the framework has training for teachers, and research efforts

Volume 28 Number 2 | Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education | 55

Copyright 201112, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.3777 (Intl), iste@iste.org, iste.org. All rights reserved.

An & Reigeluth

for improving technology integra- to teachers, include such barriers as 4. Teachers perceptions of the effective-

tion practices, high-level technology lack of resources, institution, subject ness of current professional develop-

use is still low. In general, high-level culture, and assessment. On the other ment programs and suggestions for

technology uses tend to be associated hand, second-order barriers are intrin- improvement

with learner-centered or constructivist sic to teachers and include such obsta- 5. Teachers support needs

practices. Rather than using technology cles as attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and

in the ways that the literature suggests, skills. Pointing out that the first- and By examining K12 teachers beliefs,

teachers tend to use technology mostly second-order barriers are inextricably perceptions, barriers, and support

for communication and low-level tasks, linked together, researchers suggest that needs in the context of learner-centered

such as word processing, drill-and-prac- it is necessary to address both types of technology integration, this study

tice activities, and exploring websites, barriers rather than addressing them aims to inform teacher educators and

many of which align minimally with separately (Ertmer, 1999; Hew & Brush, administrators of how they can better

core pedagogical goals (Becker, 1994, 2007). Hew and Brush (2007) analyzed support teachers in creating technology-

2000; Brush & Saye, 2009; Ertmer, 2005; previous research studies from 1995 to enhanced, learner-centered classrooms.

Russell, Bebell, ODwyer, & OConnor, spring 2006 and identified six major

2003; Strudler & Wetzel, 1999; Willis, categories of the barriers faced by K12 Method

Thompson, & Sadera, 1999; U.S. Depart- schools when integrating technology The researchers used an online survey

ment of Education, 2003). into the curriculum for instructional to collect data in this study. The survey

To better understand and improve purposes: (a) resources, (b) knowledge included the following eight sections:

ineffective or inadequate technol- and skills, (c) institution, (d) attitudes

1. Demographic questions

ogy integration practices, researchers and beliefs, (e) assessment, and (f) sub-

2. Technology beliefs

have examined factors that may affect ject culture. Then they classified strate-

3. Learner-centered instruction

K12 teachers technology integration gies to overcome the barriers into five

4. Current practices in creating tech-

positively or negatively. Becker (2000) categories: (a) obtaining the necessary

nology-enhanced, learner-centered

argued that certain conditions can help resources, (b) having a shared vision

classrooms

teachers use technology effectively: and technology integration plan, (c)

5. Perceived barriers to creating tech-

facilitating changes in attitudes/beliefs,

However, under the right con- nology-enhanced, learner-centered

(d) professional development, and (e)

ditionswhere teachers are classrooms

reconsidering assessment.

personally comfortable and at 6. Perceived effectiveness of current

Although previous research provides

least moderately skilled in using professional development programs/

useful insights into the factors that affect

computers themselves, where suggestions for improvement

technology integration in general and

the schools daily class schedule 7. Support needs

how to improve professional develop-

permits allowing time for students 8. Addresses

ment efforts, few have examined issues

to use computers as part of class

related to learner-centered technology The researchers developed survey

assignments, where enough equip-

integration. To effectively help teachers items based on an extensive literature

ment is available and convenient

create technology-enhanced, learner-cen- review and feedback from 11 teachers

to permit computer activities to

tered classrooms, it is essential to under- who participated in the pilot testing

flow seamlessly alongside other

stand: (a) how they perceive learner-cen- of the survey instrument. The survey

learning tasks, and where teachers

tered instruction as well as technology; originally included more open-ended

personal philosophies support a

(b) what kinds of barriers they face in questions, but teachers often pro-

student-centered, constructivist

creating technology-enhanced, learner- vided short or vague answers to these

pedagogy that incorporates col-

centered classrooms; and (c) what kind questions. Therefore, the researchers

laborative projects defined partly

of support they need to create such class- added more Likert-style questions and

by student interestcomputers

rooms. Therefore, this study focuses on changed wordings. The Results section

are clearly becoming a valuable

the following: describes more information about the

and well-functioning instructional

survey.

tool. (Becker, 2000, p. 25)

1. Teachers beliefs and attitudes toward The first author sent e-mail invita-

There are many barriers to inte- the use of technology in learning and tions, including the link to the online

grating technology into teaching and teaching survey, to K12 teachers in northeast

learning. Ertmer et al. (1999) classified 2. Teachers perceptions of learner- Texas and southwest Arkansas in the

technology integration barriers in two centered instruction United States. To recruit participants,

major categories: first- and second- 3. Teachers perceptions of barriers the researchers used Wal-Mart gift cards

order barriers. First-order barriers, to creating technology-enhanced, as participant incentives. The research-

which refer to obstacles that are external learner-centered classrooms ers informed the participants that they

56 | Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education | Volume 28 Number 2

Copyright 201112, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.3777 (Intl), iste@iste.org, iste.org. All rights reserved.

Learner-Centered Technology Integration

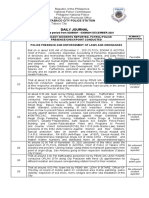

Table 1. Technology beliefs (n = 126)

Statement M SD

1. I support the use of technology in the classroom. 4.83 .39

2. A variety of technologies are important for student learning. 4.78 .45

3. Incorporating technology into instruction helps students learn. 4.73 .48

4. Technology enables me to accomplish tasks more effectively and efficiently. 4.64 .61

5. Technology is an important part of teaching and learning. 4.56 .52

6. I am willing to take some time to learn and use new technologies. 4.52 .70

7. Teachers should keep up with new technologies. 4.50 .67

8. Incorporating technology into the curriculum isnt my job. 1.61 (4.39) .75

9. Teachers should focus on content and pedagogy, and technologists should be in charge of the technology. 1.69 (4.31) .71

10. Technology may draw students attention but is not helpful for student learning. 1.76 (4.24) .89

would receive a $10 Wal-Mart gift card if Results Perceptions of Learner-Centered Instruction

they completed the survey and provided The Perceptions of Learner-Centered

their mailing address at the end of the Technology Beliefs Instruction (LCI) section of the survey

survey. This study was supported by a Brush, Glazewski, and Hew (2008) de- included 11 Likert-style items and 3

research grant from the previous institu- veloped 12 items that addressed teachers open-ended questions. Table 2 (p. 58)

tion of the first author. technology beliefs. By adapting them, reports the means and standard de-

The researchers conducted the the researchers developed 10 items to viations in rank order. The numbers

survey, including Likert-style ques- measure K12 teachers technology represent responses on the same 5-point

tions and open-ended questions, from beliefs (see Table 1). A 5-point scale was Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5.

April through May 2010. One hun- used for responses: 1 = strongly disagree, Overall, participants had positive

dred twenty-six teachers participated 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and perceptions of LCI. About 70% of par-

in the study (32% response rate). The 5 = strongly agree. ticipants agreed or strongly agreed that

participants were from 27 schools (14 Findings from the Technology Beliefs they were learner-centered teachers, and

elementary schools, 4 middle schools, section of the survey revealed K12 27.6% were neutral. Only a few teachers

and 9 high schools) in a number of teachers positive attitudes toward the thought that learner-centered approach-

different rural school districts, includ- use of technology in teaching and learn- es are time-consuming, diminish the

ing Texarkana Independent School ing. This is consistent with Brush et al.s amount of content they can teach, are

District (TISD), Texarkana Arkansas (2008) field-test results, even though incompatible with their subject areas, or

School District (TASD), and Pleasant their participants were preservice teach- require too much work. A majority of

Grove Independent School District. ers. Table 1 reports technology beliefs teachers believed that LCI is challeng-

The school environments varied from means (M) and standard deviations (SD) ing but rewarding (M = 4.14, SD = .73).

technology poor to technology rich. are reported in rank order. The numbers Participant responses to open-ended

Of the sample, 93% were female. The represent responses on a 5-point Likert questions also revealed that most par-

teachers had an average of 10.2 years of scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) ticipants had learner-centered beliefs.

teaching experience. They ranged in age to 5 (strongly agree). Items in italics are Whereas about 40% indicated that

from 20s to 60s (2125: 10%, 2630: negatively worded, so the transposed they had enough knowledge about LCI,

21%, 3135: 17%, 3640: 14%, 41-45: value is listed in parentheses. a majority of the participants wanted

14%, 4650: 9%, 5155: 9%, 5660: 6%, Overall, participants believed that to learn more about it (M = 4.14, SD=

6165: 1%). technology, as an important part of teach- .63). This seemed to be contradictory at

The researchers collected both quan- ing and learning, helps students learn first, but qualitative data showed that,

titative and qualitative data from the (M = 4.73, SD = .48) and enables them although many teachers understood

online survey. Quantitative data were to accomplish tasks more effectively and the basic ideas of LCI, they still wanted

analyzed by using descriptive statistics. efficiently (M = 4.64, SD = .61). Most to learn more about learner-centered

Qualitative data were analyzed using the participants indicated that they supported pedagogy, especially practical strategies

constant comparative method (Glaser & the use of technology in the classroom (M for the implementation of LCI.

Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). = 4.83, SD = .39) and were willing to take

All responses were examined, coded, time to learn and use new technologies Current Practices

and constantly compared to other data. (M = 4.52, SD = .70). They also indicated This section of the survey included 18

In the process, some coded data were a belief that incorporating technology into items rated using the same 5-point Likert

renamed or merged into new categories. the curriculum was part of their job. scale ranging from 1 to 5. Table 3 (p. 58)

Volume 28 Number 2 | Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education | 57

Copyright 201112, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.3777 (Intl), iste@iste.org, iste.org. All rights reserved.

An & Reigeluth

Table 2. Perceptions of Learner-Centered Instruction

Statement M SD

1. My job is to teach the material. If some students dont learn it, that is their problem. 1.46 (4.54) .61

2. Learner-centered approaches require too much work for me. 1.75 (4.25) .72

3. Learner-centered approaches are incompatible with my subject area. 1.81 (4.19) .83

4. I want to learn more about learner-centered instruction. 4.14 .63

5. Learner-centered instruction is challenging but rewarding. 4.14 .73

6. Learner-centered approaches diminish the amount of content I can teach. 1.87 (4.13) .82

7. Learner-centered approaches are too time-consuming. 1.89 (4.11) .80

8. I am a learner-centered teacher. 3.82 .76

9. I am not very familiar with learner-centered approaches. 2.21 (3.79) .89

10. My students are passive and not always responsible. They are not ready for learner-centered approaches, in which they take responsibility for their learning. 2.35 (3.65) .92

11. I have enough knowledge about learner-centered instruction. 3.15 .99

Table 3. Current Practices in Creating Learner-Centered Classrooms

Statement M SD

1. I provide positive emotional support and encouragement to students. 4.61 .49

2. I have high expectations of every student. 4.61 .53

3. I help students feel like they belong in the class. 4.53 .52

4. I am sensitive to student differences in learning styles, culture, values, perspectives, customs, and so forth. 4.40 .59

5. I allow students to express their own unique thoughts and beliefs. 4.36 .63

6. I encourage students to work collaboratively with other students. 4.31 .63

7. I monitor individual process continually in order to provide feedback on growth and progress. 4.30 .67

8. I provide learning experiences that are relevant and meaningful to individual students. 4.28 .57

9. I provide personalized learning experiences that take into account the different needs of individual students. 4.27 .58

10. I provide learning activities or tasks that stimulate students higher-order thinking and self-regulated learning skills. 4.27 .64

11. I give students increasing responsibility for the learning process. 4.25 .66

12. I provide activities that are personally challenging to each student. 4.23 .62

13. I help students in developing and using effective learning strategies. 4.16 .57

14. I assess different students differently. 4.06 .76

15. I help students develop self- and peer-assessment skills. 3.99 .84

16. I provide structure without being overly directive. 3.96 .80

17. I allow students to work at their own individual pace. 3.90 .78

18. I include students in decisions about how and what they learn and how that learning is assessed. 3.88 .79

reports means and standard deviations count the different needs of individual barrier) to 3 (a major barrier). Table 4

in rank order. All participants indicated students (M = 4.27, SD = .58). In terms reports perceived barriers means and

that they were providing positive emo- of assessment, 82% indicated that they standard deviations ) in rank order. Lack

tional support and encouragement to assessed different students differently (M of technology, lack of time, and assess-

their students (M = 4.61, SD = .49). Most = 4.06, SD = .76). Participants gave the ment were identified as the major bar-

participants indicated that they had lowest ranking to the statements I allow riers to creating technology-enhanced,

high expectations of every student (M = students to work at their own individual learner-centered classrooms, but their

4.61, SD = .53); were sensitive to student pace and I include students in deci- mean scores are relatively low. About

differences in learning styles, culture, sions about how and what they learn 57% perceived lack of technology and

values, perspectives, and customs (M = and how that learning is assessed. time as a barrier or a major barrier. A

4.40. SD = .59); and helped students feel little more than half of the participants

like they belong in the class (M = 4.53, Perceived Barriers (51%) perceived assessment as a barrier

SD = .52). Most (93%) agreed or strongly The Perceived Barriers section of the or a major barrier.

agreed that they provided personalized survey included 11 items rated using In terms of knowledge, about 35%

learning experiences that take into ac- a 3-point scale ranging from 1 (not a indicated that lack of knowledge about

58 | Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education | Volume 28 Number 2

Copyright 201112, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.3777 (Intl), iste@iste.org, iste.org. All rights reserved.

Learner-Centered Technology Integration

Table 4. Barriers to Creating Technology-Enhanced, Learner-Centered Classrooms

Statement M SD

1. Lack of technology 1.74 .74

2. Lack of my time 1.71 .69

3. Assessment (school and national high-stakes testing) 1.66 .73

4. Institutional barriers (school leadership, school schedule, school rules) 1.46 .59

5. Lack of my knowledge about learner-centered instruction (methods training) 1.44 .59

6. Lack of my knowledge about ways to integrate technology into learner-centered instruction (training in technology integration techniques) 1.44 .59

7. Lack of tech support 1.39 .62

8. Subject culture (the general set of institutionalized practices and expectations which have grown up around a particular school subject) 1.35 .54

9. Lack of my knowledge about technology (tech training) 1.33 .48

10. My attitude toward learner-centered instruction 1.05 .29

11. My attitude toward technology 1.03 .22

Table 5. Perceived Effectiveness of Current Professional Development Programs

Statement M SD

1. They help me improve my technology knowledge. 3.78 .91

2. They help me understand how teaching and learning change when particular technologies are used. 3.47 1.05

3. They help me improve my pedagogical knowledge. 3.46 .91

4. They help me create a technology-enhanced, learner-centered classroom. 3.39 1.02

5. They help me improve my content knowledge about the subject matter I teach. 3.36 1.09

6. They help me create a learner-centered classroom. 3.18 1.05

7. I am satisfied with my current professional development programs and activities. 3.16 1.09

8. They provide subject-specific technology integration ideas. 3.13 1.00

9. They focus primarily on how to merely operate the technology. 2.93 1.07

10. They provide some technology integration ideas but they are too general to be applied easily to my classroom. 2.85 1.00

learner-centered instruction and ways deviations. About 43% indicated that give us are so broad it is hard to target

to integrate technology into learner-cen- they were satisfied with their current it to one specific subject area, especially

tered instruction are barriers to creating professional development programs math, and Not enough subject-specific

technology-enhanced, learner-centered and activities (M = 3.16, SD =1.09). and certain learner-specific informa-

classrooms. Participants gave the lowest Participants gave the highest ranking to tion. We need more ideas for our certain

ranking to my attitude toward technolo- the statement: They help me improve subject areas involving technology.

gy and my attitude toward learner-cen- my technology knowledge. About 70% Programs cram too much information

tered instruction. Most (98%) believed indicated that their professional devel- into short trainings. Participants reported

their attitude toward learner-centered opment programs helped them improve that their current professional programs

instruction were not a barrier. their technology knowledge. provide way too much information at

The researchers identified other bar- Participant responses to open-ended one time, and they dont have enough

riers that Table 4 does not address from questions identified the major weak- time to practice and thoroughly learn

participant responses to an open-end nesses of current professional develop- what is being presented to them.

question. These include lack of funding, ment programs as:

limited resources, student behavior, class In terms of technology training, partici-

size, inclusion of severe-needs students, Programs are too broad and not sub- pants pointed out that many technology

and parents who complain about chal- ject specific. A number of participants training sessions are geared toward new

lenging activities. pointed out that most of their current users, and they often teach about technol-

professional development programs tend ogy that is not available to teachers. Partic-

Evaluation of Current Professional to be very broad and do not provide sub- ipant responses included: They are geared

Development Programs ject-specific information or examples. towards a new user so many times I

This section included 10 items rated us- Participant responses included: Most of find myself bored or attending something

ing the same 5-point Likert scale ranging the professional development we have is that I have already prior knowledge of, or

from 1 to 5. Table 5 reports the per- to merely teach us how to use the spe- have been using already, and The prob-

ceived effectiveness means and standard cific system, and any examples that they lem with our professional development

Volume 28 Number 2 | Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education | 59

Copyright 201112, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.3777 (Intl), iste@iste.org, iste.org. All rights reserved.

An & Reigeluth

is that many times we have had to attend classrooms, participants indicated that much cool stuff, but they still have

technology training for technology that they needed (a) more equipment, tech- difficulty applying it for their students

we do not have in the classroom and are nology, or funding; and (b) more train- learning. As noted already, technology

not expected to receive. ing, workshops, models, and examples. integration requires much more than

Several participants reported that They also believed that schools need to technical skills. Technology integration

they had no or few opportunities for (c) focus more on students and learner- training must help teachers develop

professional development. Specifically, centered instruction and (d) focus less TPACK by providing them with subject-

kindergarten teachers mentioned that on state test scores. Specific participant specific technology integration ideas

most professional development programs responses included: and opportunities to explore technolo-

were for older students. On the other gies in authentic teaching and learning

More focus starting in K on learner-

hand, some people mentioned that their contexts. Teachers should be able to

centered instruction.

districts provided many opportunities to build technology skills in the context

Learner-centered strategies need

explore and learn more about technology of designing learner-centered learning

to start in elementary so that they

and learner-centered instruction. activities in their subject areas (Brush &

[students] will be comfortable with

Saye, 2009; Ertmer, 2003; Hew & Brush,

this approach.

2007; Mishra & Koehler, 2006; Koehler &

Support Needs Schools need to focus on students

Mishra, 2008; Polly & Hannafin, 2010).

beginning at the youngest age and

Ways to improve professional develop- More training on learner-centered in-

not on the TAKS test. They need to

ment programs. How could professional struction. Becker (2000) pointed out that

start with the 4-year-olds and build

development programs be improved to teachers are much more constructivist

a base of knowledge using technol-

better help teachers create technology- in philosophy than in actual practice.

ogy. The students with even the most

enhanced, learner-centered classrooms? Research studies have documented

severe disability should be included

Participants suggested that they (a) allow incongruence between teachers beliefs

in all technology decisions.

time for hands-on practice; (b) be subject- and practices (Lim & Chan, 2007; Pe-

Schools need to quit focusing so

specific; (c) provide more training about terson, 1990; Polly & Hannafin, in press;

much on the state tests and more on

learner-centered instruction; and (d) stop Wilson, 1990). It is possible that teachers

the students, and they will see more

telling and show how to create technology- who are learner-centered in philosophy

well-rounded students as well as

enhanced, learner-centered classrooms. are teacher-centered in actual practice.

good test scores.

Specific participant responses included: Learner-centered philosophy does not

A small number of the participants necessarily lead to learner-centered

Give teachers time during in-service

pointed out the need for mindset practice. Many things can cause such

training to really get the hands-on

change, customized or individualized inconsistency. Based on our findings,

training we need to provide effective

support, tech support, more planning it appears that lack of knowledge about

instruction to our students.

time to research and develop ideas, more LCI might prevent teachers from creat-

Break it up into area-specific work-

freedom to incorporate new ideas, lon- ing learner-centered classrooms, even

shops. Right now, all teachers are

ger class periods, and smaller classes. though they are learner-centered in

thrown into the cafeteria together

philosophy. Most participants in this

to all learn the same thing during

Discussion and Conclusion study indicated that they wanted to learn

in-service. That really doesnt work...

The findings of this study are from 126 more about LCI, especially practical

What English teachers need to learn

teachers in northeast Texas and south- strategies. Many of them suggested that

is different than what the Computer

west Arkansas. Their generalizability is professional development programs

teacher or the Art teacher needs to

unknown. However, they provide useful provide more training on LCI. It is clear

know but the district doesnt want

insights into how to support teachers in that there is a need for more training on

to spend the time or money to train

creating technology-enhanced, learner- how to implement LCI.

small groups. They prefer the one

centered classrooms. Customized and learner-centered

size fits all mentality.

training. Pointing out the different needs

More training about learner- Implications for Professional Development

of different teachers, the participants of

centered classrooms

Strengthened links among technology, this study reported that the one size fits

Have someone come in and dem-

pedagogy, and content. The results of this all approach does not work. They also

onstrate this type of classroom. Give

study show that much technology inte- suggested that professional development

lesson plans, activities, and ways to

gration training appears to focus mainly programs provide more time for hands-

organize and get started.

on technology knowledge and skills on practice rather than cramming a

Institutional support. In terms of while overlooking the dynamic relation- large amount of information into a short

institutional support needed to create ships between technology, pedagogy, and training. To better help teachers create

technology-enhanced, learner-centered content. As a result, teachers learn about technology-enhanced, learner-centered

60 | Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education | Volume 28 Number 2

Copyright 201112, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.3777 (Intl), iste@iste.org, iste.org. All rights reserved.

Learner-Centered Technology Integration

classrooms, professional development development programs is insufficient. examine the issues related to learner-

must take into account teachers needs; As the participants suggested, schools centered technology integration in

provide active, hands-on, and learner- need to focus more on learner-centered greater depth using observation and

centered learning experiences; and instruction and less on state test scores, interviews in addition to an online sur-

provide personalized support. beyond providing technology tools vey. Also, it would be useful to involve

Vicarious experiences. The effec- and training. For this to happen, more students and other stakeholders as well

tiveness of observational or vicarious fundamental changes to our education as teachers. Third, further research is

learning is well known (Bandura, 1997). system would need to occur. Pointing out needed to explore various ways to design

Previous research suggests that vicari- that our current education system was and implement professional develop-

ous experiences, especially observing designed more for sorting than for learn- ment programs that are learner-centered

successful others, can not only provide ing, Reigeluth (1994, 1999b) contends and subject-specific; show how to create

how-to information but also increase that there is a need to change our current technology-enhanced, learner-centered

teachers confidence for performing paradigm of public education to one bet- classrooms; provide hands-on learning

successfully (Ertmer, 2005; Schunk, ter suited to the educational needs of the experiences; and help teachers develop

2000). The participants of this study also information age. TPACK. Finally, future research could

suggested that professional develop- Specifically, Reigeluth and Duffy explore ways to help all stakeholders to

ment programs stop telling and show or (2008) argue that three paradigm chang- evolve their mindsets about education.

demonstrate how to create technology- es must occur in parallel to achieve a

enhanced, learner-centered classrooms. paradigm that is learning-focused rather Author Notes

However, locating high-quality models than sorting-focused: (a) transforming Yun-Jo An is an assistant professor in the Depart-

and exposing teachers to the models are ment of Educational Innovation at the University of

teaching and learning to a paradigm that

West Georgia. She received her PhD in instructional

difficult. Realizing the difficulties in- is customized and attainment-based, systems technology from Indiana University Bloom-

volved in providing various experiences, (b) transforming the school systems ington. She has practical experience in the areas of

researchers have suggested presenting social infrastructure to a participatory instructional design, e-learning course development,

models via electronic media, such as organization design, and (c) trans- corporate training, and multimedia development.

video or web-based tools (Albion, 2003; Her current research focuses on learner-centered

forming the relationship between the

technology integration, teacher education, and

Brush & Saye, 2009; Ertmer et al., 2003; school system and its environment to a problem-based learning. Please send correspondence

Ertmer, 2005). collaborative and proactive stance. As regarding this article to Yun-Jo An, University of

Communities of practice or social they emphasize, the paradigm change West Georgia, Educational Annex, Carrollton, GA

networks. Noting that teachers beliefs requires helping all stakeholders to 30118. E-mail: yan@westga.edu

and practices are continually shaped by evolve their mindsets about education. Charles Reigeluth has a BA in economics from

the values, opinions, and expectations of Even if teachers have all the knowledge, Harvard University and a PhD in instructional

influential others, researchers have sug- skills, attitudes, and tools they need, psychology from Brigham Young University.He

taught high school science for three years.He

gested building communities of practice, they will not be able to create effective

has been a professor in the Instructional Systems

social networks, or collegial groups in learner-centered classrooms if they still Technology Department at Indiana Universitys

which teachers can share and explore new have to cover a large amount of content School of Education since 1988.His research focuses

teaching methods and tools and help each in a short time and focus on preparing on paradigm change in public education utilizing

other (Becker, 1994; Becker & Riel, 1999; students for high-stakes tests. It appears digital technology and brain-based, personalized

educational methods. He is also advising the US Air

Ertmer, 2005; Kopcha, 2010; Marcinkie- that effective learner-centered learning

Force on the application of instructional theory to

wicz & Regstad, 1996; Orill, 2001; Putnam experiences require all those involved improving digital learning.Professor Reigeluth is

& Borko, 2000). Appropriate communities with the system, including administra- internationally known for his work on instructional

of practice or social networks have the po- tion, parents, and students, to support methods and theories.. Please send correspondence

tential to provide ongoing support outside the learning-focused paradigm and be regarding this article to Charles Reigeluth, Indiana

University, W. W. Wright Education Building, Room

the formal training. willing to perform the new roles that the

2236, 201 North Rose Avenue, Bloomington, IN

new paradigm requires. 47405. E-mail: reigelut@indiana.edu

Paradigm Change

Interestingly, teachers appeared to face Suggestions for Future Research

References

more first-order barriers, which are Further studies might test the general- Albion, P. (2003). PBL + IMM = PBL2: Problem

external to teachers, rather than second- izability of these results by examining based learning and interactive multimedia

order barriers, when creating technology- K12 teachers beliefs, perceptions, development. Journal of Technology and

enhanced, learner-centered classrooms. barriers, and support needs in the con- Teacher Education, 11, 243257.

American Psychological Association Board of

Lack of technology and time, assessment, text of creating technology-enhanced,

Educational Affairs. (1997). Learner-centered

and institutional structure turned out learner-centered classrooms in differ- psychological principles: A framework for

to be the top perceived barriers. This ent school districts, states, or coun- school reform and redesign. Washington, DC:

suggests that improving professional tries. Second, future research could American Psychological Association.

Volume 28 Number 2 | Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education | 61

Copyright 201112, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.3777 (Intl), iste@iste.org, iste.org. All rights reserved.

An & Reigeluth

American Psychological Association Task Force Ertmer, P. A., Lehman, J. D., Park, S. H., Cramer, Reigeluth, C. M. (1994). Envisioning a new

on Psychology in Education. (1993). Learner- J., & Grove, K. (2003) Adoption and use system of education. In C. M. Reigeluth & R. J.

centered psychological principles: Guidelines for of technology-supported learner-centered Garfinkle (Eds.), Systemic change in education

school redesign and reform. Washington, DC: pedagogies: Barriers to teachers implementation. (pp. 5970). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational

American Psychological Association. Retrieved from http://www.edci.purdue.edu/ Technology Publications.

Bandura, A. (1977) Social learning theory. ertmer/docs/EdMedia_TKB_paper.PDF Reigeluth, C. M. (1999a). Visioning public

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery education in America. Educational Technology,

Bebell, D., Russell, M., & ODwyer, L. (2004). of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative 39(5), 5055.

Measuring teachers technology uses: Why research. Chicago: Aldine. Reigeluth, C. M. (1999b). What is instructional-

multiple-measures are more revealing. Journal Hew, K. F., & Brush, T. (2007). Integrating design theory and how is it changing? In C.M.

of Research on Technology in Education, 37(1), technology into K12 teaching and learning: Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-design theories

4563. Current knowledge gaps and recommendations and models: A new paradigm of instructional

Becker, H. J. (1994). How exemplary computer- for future research. Educational Technology theory (Volume II, pp. 529). Mahwah, NJ:

using teachers differ from other teachers: Research and Development, 55(3), 223252. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Implications for realizing the potential of Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing Reigeluth, C. M., & Duffy, F. M. (2008). The AECT

computers in schools. Journal of Research on TPCK. In AACTE Committee on Innovation FutureMinds initiative: Transforming Americas

Computing in Education, 26, 291321. and Technology (Eds.), Handbook of school systems. Educational Technology, 48(3),

Becker, H. J. (2000). Findings from the teaching, technological pedagogical content knowledge for 4549.

learning, and computing survey: Is Larry Cuban educators (pp. 329). New York: Routledge. Russell, M., Bebell, D., ODwyer, L., & OConnor,

right? Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8(51), Kopcha, T. J. (2010). A systems-based approach K. (2003). Examining teacher technology

Retrieved June 29, 2010, from http://epaa.asu. to technology integration using mentoring and use: Implications for preservice and inservice

edu/ojs/article/viewFile/442/565 communities of practice. Educational Technology teacher preparation. Journal of Teacher

Becker, H. J., & Riel, M. M. (1999). Teacher Research and Development, 58(2), 175190. Education, 54(4), 297310.

professionalism and the emergence of Lim, C. P., & Chan, B. C. (2007). MicroLESSONS Schunk, D. H. (2000). Learning theories: An

constructivist-compatible pedagogies. in teacher education: Examining pre-service educational perspective (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle

Retrieved September 9, 2010, from http:// teachers pedagogical beliefs. Computers & River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

www.crito.uci.edu/tlc/findings/special_ Education, 48(4), 474494. Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand:

report2/aerj-final.pdf Marcinkiewicz, H. R., & Regstad, N. G. (1996). Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. Using subjective norms to predict teachers Researcher, 15(2), 414.

R. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, computer use. Journal of Computing in Teacher Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching:

experience, and school. Washington, D.C.: Education, 13(1), 2733. Foundations of the new reform. Harvard

National Academy Press. McCombs, B. L., & Whisler, J. S. (1997). The Educational Review, 57(1), 122.

Brush, T., & Saye, J. W. (2009). Strategies for learner-centered classroom and school: Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of

preparing preservice social studies teachers to Strategies for increasing student motivation and qualitative research: Grounded theory

integrate technology effectively: Models and achievement. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. procedures and techniques. Newbury Park,

practices. Contemporary Issues in Technology Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological CA: Sage.

and Teacher Education, 9(1), 4659 pedagogical content knowledge: A new Strobel, J., & van Barneveld, A. (2009). When

Brush, T., Glazewski, K. D., & Hew, K. F. framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers is PBL more effective? A meta-analysis of

(2008). Development of an instrument to College Record, 108(6), 10171054. meta-analyses comparing PBL to conventional

measure preservice teachers technology Oblinger, D. G. (2008). Growing up with Google: classrooms. The Interdisciplinary Journal of

skills, technology beliefs, and technology What it means to education. Emerging Problem-based Learning, 3(1), 4458.

barriers. Computers in the Schools, 25(12), Technologies for Learning, 3, 1129. Strudler, N., & Wetzel, K. (1999). Lessons from

112125. Orrill, C. H. (2001). Building technology-based, exemplary colleges of education: Factors

Cheang, K. I. (2009). Effects of learner-centered learner-centered classrooms: The evolution affecting technology integration in preservice

teaching on motivation and learning strategies of a professional development framework. programs. Educational Technology Research and

in a third-year pharmacotherapy course. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(4), 6381.

American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, Development, 49(1), 1534. U.S. Department of Education. (2003). Federal

73(3), Article 42. Peterson, P. L. (1990). Doing more of the same: funding for educational technology and how it

Cornelius-White, J. H. D., & Harbaugh, A. P. Cathy Swift. Educational Evaluation and Policy is used in the classroom: A summary of findings

(2009). Learner-centered instruction: Building Analysis, 12(3), 261280. from the integrated studies of educational

relationships for student success. Thousand Oaks, Polly, D., & Hannafin, M. J. (2010). Reexamining technology. Washington, DC: Office of the

CA: Sage. technologys role in learner-centered Under Secretary, Policy, and Program Studies

DiMartino, J., Clark, J., & Wolk, D. (Eds.) (2003). professional development. Educational Service.

Personalized learning: Preparing high school Technology Research and Development, 58(5), Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered teaching: Five

students to create their futures. Lanham, MD: 557571. key changes to practice. San Francisco: Jossey-

The Scarecrow Press. Polly, D., & Hannafin, M. J. (2011). Examining Bass.

Ertmer, P. A. (1999). Addressing first- and how learner-centered professional development Willis, J., Thompson, A., & Sadera, W. (1999).

second-order barriers to change: Strategies for influences teachers espoused and enacted Research on technology and teacher education:

technology integration. Educational Technology practices. Journal of Educational Research, Current status and future directions.

Research and Development, 47(4), 4761. 104(2), 120130. Educational Technology Research and

Ertmer, P. A. (2005). Teacher pedagogical beliefs: Prensky, M. (2007). Digital game-based learning. Development, 47(4), 2945.

The final frontier in our quest for technology St. Paul, MN: Paragon House. Wilson, S. M. (1990). A conflict of interests: The

integration? Educational Technology Research Putnam, R. T., & Borko, H. (2000). What do new case of Mark Black. Educational Evaluation and

and Development, 53(4), 2539. views of knowledge and thinking have to say Policy Analysis, 12(3), 309326.

about research on teacher learning. Educational

Researcher, 29(1), 415.

62 | Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education | Volume 28 Number 2

Copyright 201112, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.3777 (Intl), iste@iste.org, iste.org. All rights reserved.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Las Math 2 Q3 Week 1Document6 pagesLas Math 2 Q3 Week 1Honeyjo Nette100% (7)

- Learner-Centered Teaching Five Key Changes To PracticeDocument6 pagesLearner-Centered Teaching Five Key Changes To Practiceapi-301639691Pas encore d'évaluation

- Learner-Centered Teaching Five Key Changes To PracticeDocument6 pagesLearner-Centered Teaching Five Key Changes To Practiceapi-301639691Pas encore d'évaluation

- Socratic Sales The 21 Best Sales Questions For Mastering Lead Qualification and AcceDocument13 pagesSocratic Sales The 21 Best Sales Questions For Mastering Lead Qualification and Acceutube3805100% (2)

- The21stcenturyclassroom 140330160731 Phpapp01Document16 pagesThe21stcenturyclassroom 140330160731 Phpapp01api-302210367Pas encore d'évaluation

- Positive Classroom EnvironmentsDocument5 pagesPositive Classroom Environmentsapi-302210367Pas encore d'évaluation

- Terry HeickDocument3 pagesTerry Heickapi-302210367Pas encore d'évaluation

- Student Centered Learning-TechnologyDocument3 pagesStudent Centered Learning-Technologyapi-302210367Pas encore d'évaluation

- Positive Classroom EnvironmentsDocument5 pagesPositive Classroom Environmentsapi-302210367Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ventures Onsite Market Awards 22062023 64935868dDocument163 pagesVentures Onsite Market Awards 22062023 64935868dhamzarababa21Pas encore d'évaluation

- List of Mines in IndiaDocument4 pagesList of Mines in IndiaNAMISH MAHAKULPas encore d'évaluation

- AKSINDO (Mr. Ferlian), 11 - 13 Mar 2016 (NY)Document2 pagesAKSINDO (Mr. Ferlian), 11 - 13 Mar 2016 (NY)Sunarto HadiatmajaPas encore d'évaluation

- International Banking & Foreign Exchange ManagementDocument4 pagesInternational Banking & Foreign Exchange ManagementAnupriya HiranwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Taking RPA To The Next LevelDocument48 pagesTaking RPA To The Next LevelRPA Research100% (1)

- Back To School Proposal PDFDocument2 pagesBack To School Proposal PDFkandekerefarooqPas encore d'évaluation

- 12-List of U.C. Booked in NGZ Upto 31032017Document588 pages12-List of U.C. Booked in NGZ Upto 31032017avi67% (3)

- RMK Akl 2 Bab 5Document2 pagesRMK Akl 2 Bab 5ElinePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1Document25 pagesChapter 1Aditya PardasaneyPas encore d'évaluation

- Canada Immigration Forms: E33106Document6 pagesCanada Immigration Forms: E33106Oleksiy Kovyrin100% (1)

- Catalogue 2015-16Document72 pagesCatalogue 2015-16PopokasPas encore d'évaluation

- BMW I3 Wheel Airbag RemovalDocument6 pagesBMW I3 Wheel Airbag RemovalAjmaster.ltPas encore d'évaluation

- Fourth Wall ViolationsDocument7 pagesFourth Wall ViolationsDanomaly100% (1)

- The Manuals Com Cost Accounting by Matz and Usry 9th Edition Manual Ht4Document2 pagesThe Manuals Com Cost Accounting by Matz and Usry 9th Edition Manual Ht4shoaib shakilPas encore d'évaluation

- Abdukes App PaoerDocument49 pagesAbdukes App PaoerAbdulkerim ReferaPas encore d'évaluation

- QinQ Configuration PDFDocument76 pagesQinQ Configuration PDF_kochalo_100% (1)

- Artikel Andi Nurindah SariDocument14 pagesArtikel Andi Nurindah Sariapril yansenPas encore d'évaluation

- Data Communication and Networks Syllabus PDFDocument2 pagesData Communication and Networks Syllabus PDFgearlaluPas encore d'évaluation

- Your Brain Is NOT A ComputerDocument10 pagesYour Brain Is NOT A ComputerAbhijeetPas encore d'évaluation

- Begc133em20 21Document14 pagesBegc133em20 21nkPas encore d'évaluation

- 2-Port Antenna Frequency Range Dual Polarization HPBW Adjust. Electr. DTDocument5 pages2-Port Antenna Frequency Range Dual Polarization HPBW Adjust. Electr. DTIbrahim JaberPas encore d'évaluation

- JournalDocument3 pagesJournalJuvz BezzPas encore d'évaluation

- Analyzing Text - Yuli RizkiantiDocument12 pagesAnalyzing Text - Yuli RizkiantiErikaa RahmaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Board-Management RelationshipDocument32 pagesThe Board-Management RelationshipAlisha SthapitPas encore d'évaluation

- Dlis103 Library Classification and Cataloguing TheoryDocument110 pagesDlis103 Library Classification and Cataloguing Theoryabbasimuhammadwaqar74Pas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 4 Qualitative Lectures 3Document28 pagesTopic 4 Qualitative Lectures 3JEMABEL SIDAYENPas encore d'évaluation

- Fiche 2 ConnexionsDocument2 pagesFiche 2 ConnexionsMaria Marinela Rusu50% (2)

- Mps Item Analysis Template TleDocument11 pagesMps Item Analysis Template TleRose Arianne DesalitPas encore d'évaluation