Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Stout 2003

Transféré par

Gabriel Mercado InsignaresCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Stout 2003

Transféré par

Gabriel Mercado InsignaresDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Assessment

http://asm.sagepub.com/

Factor Analysis of the Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe)

Julie C. Stout, Rebecca E. Ready, Janet Grace, Paul F. Malloy and Jane S. Paulsen

Assessment 2003 10: 79

DOI: 10.1177/1073191102250339

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://asm.sagepub.com/content/10/1/79

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Assessment can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://asm.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://asm.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://asm.sagepub.com/content/10/1/79.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Mar 1, 2003

What is This?

Downloaded from asm.sagepub.com at Afyon Kocatepe Universitesi on May 12, 2014

ASSESSMENT Stout

ARTICLE

10.1177/1073191102250339

et al. / FrSBe FACTOR ANALYSIS

Factor Analysis of the Frontal

Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe)

Julie C. Stout

Indiana University

Rebecca E. Ready

Janet Grace

Paul F. Malloy

Brown University

Jane S. Paulsen

University of Iowa

The Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe), formerly called the Frontal Lobe Personality

Scale (FLOPS), is a brief behavior rating scale with demonstrated validity for the assess-

ment of behavior disturbances associated with damage to the frontal-subcortical brain cir-

cuits. The authors report an exploratory principal factor analysis of the FrSBeFamily

Version in a sample including 324 neurological patients and research participants, of which

about 63% were diagnosed with neurodegenerative diseases (Huntingtons, Parkinsons,

and Alzheimers diseases). The three-factor solution accounted for a modest level of vari-

ance (41%) and confirmed a factor structure consistent with the three subscales proposed on

the theoretical basis of the frontal systems. Most items (83%) from the FrSBe subscales of

Apathy, Disinhibition, and Executive Dysfunction loaded saliently on three corresponding

factors. The FrSBe factor structure supports its utility for assessing both the severity of the

three frontal syndromes in aggregate and separately.

Keywords: disinhibition; executive function; apathy; frontal

Damage to the prefrontal cortex is associated with a lies and on society at large. Neuropsychological methods

wide range of behavioral changes, including disinhibition, for assessing cognitive changes associated with frontal

irritability, apathy, decreased initiation, emotional lability, systems damage have been a focus of study for many

distractibility, irresponsibility, as well as problems with years, and neuropsychological tests are available that ef-

executive functions, working memory, attention, abstract fectively address many of these cognitive disturbances

thinking, mental flexibility, and recall (for a recent review, (Lezak, 1995; Spreen & Strauss, 1998). Fewer measures

see Lichter & Cummings, 2001b). These symptoms pose a are available to assess behavioral disturbances lying out-

threat to personal autonomy and increase burden on fami- side of the cognitive realm, although recent years have

Jessica Jones at Indiana University provided excellent assistance in preparation of this manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge the

contributions of Mary Wyman at Indiana University, who assisted in compiling data. We thank Drs. Guerry Peavy and David Salmon at

the University of California, San Diego Alzheimer Disease Research Center, for providing data from patients with Alzheimers disease.

Beth Turner and Laura Stierman provided assistance in data compilation at the University of Iowa. The project was supported by National

Institutes of HealthNational Institute of Aging AGO-5131 (UCSD-ADRC) and T32AG00214 (predoctoral fellowship to second au-

thor). Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Julie C. Stout, Department of Psychology, Indiana University, 1101

E. 10th St., Bloomington, IN 47405-7007; e-mail: jcstout@indiana.edu.

Assessment, Volume 10, No. 1, March 2003 79-85

DOI: 10.1177/1073191102250339

2003 Sage Publications

Downloaded from asm.sagepub.com at Afyon Kocatepe Universitesi on May 12, 2014

80 ASSESSMENT

seen an increase in the availability of such measures (the & Salloway, 2001; Paulsen et al., 1996, 2000; Zawacki

Neuropsychiatric Inventory, Cummings et al., 1994; the et al., 2002). The Family Version of the FrSBe has been

Frontal Systems Behavior Scale [FrSBe], formerly re- used in the majority of the reports, including the primary

ferred to as the Frontal Lobe Personality Scale [FLOPS], validity study of the FrSBe (Grace et al., 1999).

Grace, Stout, & Malloy, 1999; the Frontal Behavior In- The FrSBe has been shown to have high internal consis-

ventory, Kertesz, Davidson, & Fox, 1997; the Apathy tency reliability, and there is growing evidence for the

Evaluation Scale, Marin, Biedrzycki, & Firincioguliari, tests validity for assessing behavioral changes associated

1991). Accurate conceptualization and measurement of with frontal systems damage (Boyle, Grace, Zawacki, Ott,

frontal behavior disturbances are essential steps for de- & Stout, 2001; Grace et al., 1999). The clinical utility of

termining their prevalence and their impact on activities the instrument is indicated by the fact that it measures

of daily living. Furthermore, the precise measurement of characteristics that are at least partly independent of cog-

treatment efficacy depends on the availability of nitive dysfunction and thus is not redundant with cognitive

psychometrically sound scales for measuring specific be- measures (Paulsen et al., 1996; Stout, Wyman, Peavy, &

havioral disturbances. Salmon, 2001; Zawacki et al., 2002). Ratings on the FrSBe

Of the scales listed above, the FrSBe is of particular in- also are associated with important outcome criteria, such

terest for characterizing behavior disturbances related to as functional status (Norton et al., 2001; Stout et al., 2001;

frontal system dysfunction.1 The FrSBe is a behavior rat- Zawacki et al., 2002).

ing scale designed to provide a total frontal disturbance Evidence is beginning to accrue that the FrSBe

score and three subscale scores made up of items devel- subscales are differentially associated with clinical fea-

oped to assess particular behavioral disturbances. Apathy, tures. For example, the Apathy Subscale of the FrSBe was

disinhibition, and executive function were chosen by the more strongly related to activities of daily living in vascu-

scales authors following an extensive search of the clini- lar dementia (Zawacki et al., 2002) and mixed dementia

cal research literature that revealed these three categories groups (Norton et al., 2001). Furthermore, Ready,

of behavior as the most frequently cited behavioral distur- Stierman, and Paulsen (2001) reported evidence of eco-

bances associated with damage to the frontal lobes and logical validity for the various subscales in a healthy un-

frontal-subcortical brain circuitry. In fact, these three fron- dergraduate student sample; the Disinhibition Subscale

tal behavior syndromes have been linked to regional dis- showed differential relationship to engaging in risky and

turbances in frontal lobe function. Specifically, damage to aggressive behaviors (Ready et al., 2001). Sufficient data

the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has been linked to prob- from neurological patients and research participants has

lems with executive function, the mesial frontal and ante- now accumulated so that it is possible to conduct a factor

rior cingulate cortex with apathy and akinesia, and the analysis of the scale items and to determine if the factor

orbitofrontal cortex with disinhibited behavior and emo- structure of the instrument corresponds to the hypothe-

tional outbursts. These behavioral disturbances are found sized three-subscale structure. This is an essential step for

in individuals who have frontal lobe damage and in indi- determining whether the psychometric features of the

viduals whose damage is at the subcortical levels in brain scale support the intended use of the measure for assessing

structures known to be linked in a regionally specific fash- overall frontal behavior disturbance, as well as differential

ion to frontal cortex (Levin, Eisenberg, & Benton, 1991; presentation of the three frontal syndromes of apathy,

Lhermitte, Pillon, & Serdaru, 1986; Lichter & Cummings, disinhibition, and executive dysfunction.

2001a; Mega & Cummings, 1994; Stuss & Benson, 1986). The goal of this study was to determine whether the fac-

The FrSBe is a 46-item behavior rating scale (Grace & tor structure of the FrSBe supports the subscale structure

Malloy, 2001). Parallel forms exist for use by a family of the scale. For this purpose, we evaluated data from a

member or close caregiver (Family Version), a staff mem- mixed group of neurological patients and research partici-

ber caring for a patient in a professional setting (Staff Ver- pants regarding the frequency ratings of recent behaviors

sion), and for self-ratings by the patient/subject (Self on the FrSBeFamily Version. The study sample was de-

Version). The FrSBe is designed to allow ratings to be signed to include a wide range of neurological disorders

made of recent behavior, and for comparison, an optional that is representative of those for whom the scale will be

retrospective rating of behavior prior to accident, injury, or used in clinical and research settings. Diagnostic heteroge-

treatment. The majority of the studies that have used the neity in the sample ensured that a wide and comprehensive

FrSBe have focused on ratings only of recent (post- range of FrSBe item scores would be represented in the

accident, postinjury, or posttreatment) behavior (Hulver- data, as is recommended for optimal factor analysis

shorn, Stout, Paulsen, & Siemers, 1999; Norton, Malloy, (Gorsuch, 1997; Reise, Waller, & Comrey, 2000).

Downloaded from asm.sagepub.com at Afyon Kocatepe Universitesi on May 12, 2014

Stout et al. / FrSBe FACTOR ANALYSIS 81

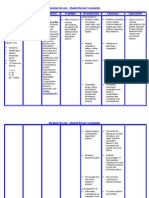

TABLE 1

Descriptive Statistics for Age, Education, and FrSBe Scales by Diagnosis (N = 324)

AD HD PD FLD Dem, NOS HI CVA

M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD

Age 75.4 7.8 46.5 12.2 68.2 7.8 69.9 8.8 70.7 11.8 41.8 17.5 60.0 19.2

Education 13.1 3.6 13.1 2.3 14.0 2.8 12.5 2.6 11.4 3.7 12.6 3.2

Apathy 41.6 10.7 39.0 11.8 34.8 10.7 48.6 7.9 35.6 12.2 32.3 10.3 36.0 11.5

Disinhibition 27.4 8.9 29.1 9.0 23.8 7.5 34.5 11.0 27.7 9.8 29.5 7.6 29.2 10.3

Executive dysfunction 55.9 12.9 46.1 14.3 40.0 11.1 57.8 13.5 48.8 16.3 41.3 10.4 44.3 15.6

Total 124.9 27.9 114.2 31.0 98.63 23.3 140.9 27.0 112.1 34.6 103.1 25.5 109.6 33.6

N 76 91 38 13 27 29 50

NOTE: AD = probable Alzheimers disease; HD = Huntingtons disease; PD = Parkinsons disease; FLD = frontal lobe dementia; Dem, NOS = dementia,

not otherwise specified, Lewy Body Variant, vascular dementia, traumatic dementia, dementia due to multiple sclerosis; HI = head injury; CVA = cerebral

vascular accident.

METHOD ticipants gave institutionally approved informed consent.

Some of these data have appeared in prior publications

Sample (Grace et al., 1999; Hulvershorn et al., 1999; Paulsen et al.,

1996; Stout et al., 2001).

The sample consisted of 324 neurological outpatients

and research participants from eight diagnostic categories Instrument

(Table 1). Alzheimers disease was diagnosed according to

The FrSBe is a 46-item behavior rating scale that mea-

National Institutes of Neurological and Communicative

sures behaviors that are clinically and theoretically linked

Disorders and Stroke criteria (McKhann et al., 1984). The

to frontal lobe damage. The items on the scale were devel-

diagnosis of Huntington Disease was made by a senior

oped from a list of descriptors used in the neuropsycho-

staff neurologist on the basis of chorea as screened on the

logical, neurological, and psychiatric literatures. Next, a

Unified Huntingtons Disease Rating Scale (Huntington

panel of experts reviewed the items, and a set of items

Study Group, 1996) and the presence of a confirmed fam-

judged to be redundant or poorly worded were eliminated.

ily history of Huntingtons disease. Parkinsons disease

Items were then assigned to three subscales. Q-sort of

was diagnosed using a clinical evaluation to document the

these items by an expert on frontal-subcortical circuits and

presence of symptoms (i.e., stooped posture, bradykinesia,

behavior revealed an acceptable level of agreement ( =

resting tremor, muscular rigidity) and to rule out other pos-

.77, p < .001). Items from the scale were worded to assess

sible diagnoses (Bannister, 1992). Hoehn and Yahr (1967)

the frequency of problems related to three behavioral do-

criteria were used to document the severity of the disorder.

mains: apathy/akinesia (Scale A, 14 items), disinhibition/

Dementia patients with prominent changes in behavior

emotional dysregulation (Scale D, 15 items), and execu-

and personality at the onset of dementia and with major

tive dysfunction (Scale E, 17 items). For all participants,

frontal lobe impairments on neuropsychological testing

ratings of recent behavior were obtained from an infor-

and single photon emission computed tomography

mant (i.e., close family member or caregiver) using the fol-

(SPECT) were diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia.

lowing instructions:

Dementia due to Lewy Bodies was diagnosed in dementia

patients with at least two of the following three character-

Below is a list of phrases used to describe someone.

istics: visual hallucinations, parkinsonian symptoms, or How well does each of these descriptions character-

fluctuating cognitive ability. Patients with dementia and an ize the person you were asked to evaluate? Please

Hachinski ischemia score greater than or equal to 7 rate these items according to the persons behavior

(Hachinski et al., 1975) were diagnosed with vascular de- in the past two weeks. Place a number in each box

mentia. These data were obtained in clinical research set- that corresponds to your rating.

tings at the Indiana University Department of Psychology,

the Brown University Department of Psychiatry and Hu- Below these instructions and reprinted at the top of each

man Behavior, the University of California San Diego Alz- page was a box containing the list of possible ratings with

heimer Disease Research Center and Genetically descriptors. For the first 35 items, informants were asked

Handicapped Persons Program, and the University of to rate each item according to the following 5-point scale:

Iowa Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology. All par- 1 = almost never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, 4 = frequently,

Downloaded from asm.sagepub.com at Afyon Kocatepe Universitesi on May 12, 2014

82 ASSESSMENT

and 5 = almost always. The 5-point scale on the last page TABLE 2

(containing the final 11 positively stated scale items) was Pattern Matrix From Principal

reversed so that 1 = almost always, 2 = frequently, 3 = Factor Analysis With Oblique Rotation

sometimes, 4 = seldom, and 5 = almost never, and a rating to Simple Structure (N = 324)

scheme was maintained such that higher ratings corre- A Priori Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

sponded to relatively more abnormal behavior. Item Abbreviation (number) Scale E D A

Shows poor judgment (19) E .73 .04 .04

Data Analysis Repeats same mistakes (7) E .70 .00 .08

Mixes up a sequence (5) E .67 .00 .00

We conducted exploratory principal component factor Is disorganized (15) E .65 .01 .13

analysis with iterated communalities on the 46 FrSBe Forgets to do things (25) E .57 .02 .11

Does not finish things (23) A .57 .02 .21

items. A three-factor solution was specified based on the

Is inflexible (26) E .54 .02 .11

theoretical conceptualization of the scale. Because we ex- Unaware of problems (13) E .54 .03 .06

pected the three factors to be correlated, as typically oc- Repeats certain actions (3) E .54 .03 .06

curs when the factors are components of a more general Says one thing, does another (22) E .53 .24 .07

a

construct (e.g., frontal system dysfunction), we used an Thinks things through (35) E .53 .00 .17

a

Pays attention (34) E .52 .11 .16

oblique rotation to simple structure as recommended by a

Is able to plan ahead (37) E .47 .06 .39

Reise and colleagues (2000). In this rotation, equal weight Cannot do two things at once (17) E .47 .01 .27

was given to the two criteria that enter into the oblique ro- Laughs or cries too easily (6)

b

D .37 .21 .10

b

tation, namely, orthogonal and correlated factors. Makes up stories (20) E .36 .25 .05

The fit of the resulting factor structure was evaluated Does embarrassing things (10) D .20 .67 .05

Makes sexual comments (9) D .05 .64 .02

using the following criteria: eigenvalues greater than or

Swears (32) D .03 .51 .02

equal to 1, scree test, and the interpretability of the factors Does things impulsively (4) D .33 .49 .17

with respect to the specific subscales proposed by the au- Is overly silly (30) D .30 .49 .10

a

thors in developing the FrSBe. We used a value greater Acts appropriately (45) D .18 .48 .14

than .40 as a criterion to define a salient factor loading as Talks out of turn (18) D .39 .47 .22

Neglects personal hygiene (11) A .02 .45 .43

recommended by Gorsuch (1997). A sample size of at a

Gets along with others (44) D .06 .42 .14

least 300 is recommended to identify item loadings of this b

Does risky things (28) D .08 .37 .03

magnitude in item-level data (Gorsuch, 1997). This rela- b

Is easily angered (2) D .24 .34 .06

b

tively large sample size also is recommended to ensure that Is hyperactive (12) D .23 .34 .16

b

the factors will emerge from error variance associated Trouble with the law (27) D .02 .27 .07

b

Loss of taste or smell (31) D .10 .24 .13

item-level data, which are known (in comparison to scales)

Lacks energy (29) A .25 .11 .61

to have relatively low intercorrelations, low reliability, Lost interest in things (21) A .24 .02 .60

varying distributions, and noncontinuous response for- Does nothing (14) A .31 .07 .60

a

mats (Gorsuch, 1997). Gets involved spontaneously (41) A .23 .14 .59

a

Starts conversations (46) A .04 .06 .51

a

Does things without reminders (42) A .22 .03 .50

Unconcerned and unresponsive (24) A .18 .06 .48

RESULTS Lacks initiative, motivation (8) A .40 .05 .48

a

Cares about appearance (39) A .04 .29 .46

a

Results of the factor analytic study supported the ex- Is sensitive to others (43) D .07 .22 .42

a, b

traction of three factors, which were consistent with the Benefits from feedback (40) E .22 .20 .37

a, b

Is interested in sex (38) A .10 .14 .36

subscales designed by the authors of the FrSBe. Below we b

Incontinence (16) A .12 .32 .36

describe the primary factor analysis results, followed by Uses memory strategies (36)

a, b

E .22 .09 .35

item-loading characteristics. a, b

Apologizes for misbehavior (33) E .04 .15 .30

b

Speaks only when spoken to (1) A .10 .07 .30

Primary Factor Analysis NOTE: E = Executive Dysfunction; A = Apathy; D = Disinhibition. Fac-

tor loadings of .40 or greater are in italics.

The three-factor solution accounted for 40.7% of the a. Reverse-keyed item.

b. Items with no salient loading on any of the three factors.

common variance among the 46 items (see Table 2). Three

lines of evidence supported the extraction of the three fac-

tors. First, the eigenvalues for the factors were all greater extracting factors beyond three in regard to accounting for

than 1. Second, the factors were above the elbow on the additional variance. Third, items from each of the three

scree plot, indicating significantly diminishing returns for FrSBe subscales tended to have primary loadings on the

Downloaded from asm.sagepub.com at Afyon Kocatepe Universitesi on May 12, 2014

Stout et al. / FrSBe FACTOR ANALYSIS 83

same factor, and thus, it was possible to make substantive the subscale to which they were theoretically assigned

interpretations of the factors based on item loadings. were Neglects personal hygiene from the Apathy sub-

The first factor, which we labeled Executive Dysfunc- scale, which cross-loaded on the Apathy and Disinhibition

tion, accounted for 29.1% of the variance. Twelve of the factors, and Has difficulty starting an activity, lacks ini-

original 16 Executive Dysfunction subscale items as well tiative, motivation, which cross-loaded on the Apathy and

as 1 item developed for the Apathy subscale had salient Executive Dysfunction factors.

loadings on the Executive Dysfunction factor. The second

factor, which we labeled Disinhibition, accounted for

7.2% of the common variance. It included salient loadings DISCUSSION

by 8 of the original 15 items from the Disinhibition

subscale as well as 1 item from the Apathy subscale. The The exploratory principal factor analysis of the FrSBe

third factor, which we labeled Apathy, accounted for 4.4% confirmed a factor structure consistent with the three

of the common variance, and 9 of the 15 items proposed in subscales that were proposed on the basis of frontal sys-

the original Apathy subscale loaded saliently on this fac- tems behavioral theory. That is, items from the individual

tor, as did one item from the Disinhibition subscale. FrSBe subscales tended to load together on each of three

Consistent with the notion that the three factors were corresponding factors, Apathy, Disinhibition, and Execu-

related to a similar underlying construct (i.e., frontal sys- tive Dysfunction. The Executive Dysfunction factor ac-

tems abnormality), the three factors were significantly (p < counted for the largest portion of the variance, but the

.01) correlated (Executive Dysfunction with Disinhibition Apathy and Disinhibition factors also emerged as impor-

r = .43, Executive Dysfunction with Apathy r = .43, tant in accounting for the patterns of responses. Thus, the

Disinhibition with Apathy r = .22). Such correlations can factor structure, in conjunction with the previous studies

be troubling when they are a result of a high level of item that have indicated construct validity of the scale, suggests

cross-loadings, because this indicates that items in the that the FrSBe is useful for assessing the severity of the

scale have such a high degree of overlap as to be ineffective three frontal syndromes in aggregate, as well as for assess-

for distinguishing the constructs targeted by the factors. ing these syndromes separately. Additional evidence of

However, only 2 of the 46 items had salient cross-loadings subscale utility has been obtained in clinical and research

as defined by .40 or greater, so item cross-loadings do settings. For example, in several studies, FrSBe subscales

not account for a significant portion of the factor were related to measures of independence in activities of

intercorrelations. daily living (Norton et al., 2001; Stout et al., 2001;

Zawacki et al., 2002).

Item Loading Characteristics The FrSBe has significant intercorrelations between

the factors, ranging from r = .22 to r = .43, a finding that is

Using the criterion of > .40 to indicate salient loading, expected when the constructs underlying the subscales are

29 of the 46 FrSBe items performed as predicted, loading related to a broader construct such as behavioral character-

saliently and solely on the expected factor. An additional 9 istics of frontal system dysfunction. Despite the interrela-

items showed strongest loadings on the expected factor, tionships, a significant level of unshared variance remains

but at a value lower than the criterion of .40. Thus, 38 of the in the factors, supporting the use of FrSBe subscales for

original 46 items loaded on the expected factor in the fac- differentiating specific patterns of behavior disturbances

tor analysis. For the remaining 8 items, 6 had their highest in individuals with frontal systems damage. Also of note,

loading on a factor other than the one corresponding only about 41% of the variance was accounted for by the

subscale to which they were assigned, and 2 had salient factor structure of the FrSBe. Thus, there is a substantial

cross-loadings both on the factor corresponding to their amount of variance in FrSBe scores that is also independ-

subscale assignment and an additional subscale (see Ta- ent of the three factors. Further studies will be necessary to

ble 2). determine whether that variance contributes to the mea-

Of the six items that loaded most highly on factors other surement of more general frontal syndromes.

than the one expected, only two had salient loadings, in- Only two of the items in the FrSBe cross-loaded

cluding Starts things but fails to finish them, which was strongly on more than one factor. Although these items

assigned to the Apathy subscale but which loaded saliently were written to measure part of a single construct, it ap-

on the Executive Dysfunction factor, and Is sensitive to pears that more than one process underlies the behaviors

the needs of other people, which was assigned to the tapped by these two items. Relatively more of the items

Disinhibition subscale but instead loaded saliently on the performed below optimal levels in the factor analysis be-

Executive Dysfunction factor and the Apathy factor, re- cause they loaded less saliently (less than .40) on any of the

spectively. The two items that failed to show specificity to three factors (17 items) or loaded saliently only on a factor

Downloaded from asm.sagepub.com at Afyon Kocatepe Universitesi on May 12, 2014

84 ASSESSMENT

other than the one corresponding to the subscale for which points to the need for additional studies to determine the

they were proposed (2 items). There are several possible predictive validity of the subscales.

reasons for such findings. For example, a few items had

very low endorsement rates and restricted variance in our

sample (e.g., trouble with the law, does risky things, un- NOTE

concerned about incontinence), which may account for 1. Throughout the article, we refer to the scale as the Frontal Systems

their failure to covary with other items in a manner that Behavior Scale (FrSBe). In publications prior to this, the scale has been

would have resulted in a salient factor loading. Although consistently referred to as the Frontal Lobe Personality Scale (FLOPS).

their psychometric properties are not ideal, they may be

useful for clinical purposes. For example, trouble with

the law is infrequently endorsed and could alert a clini- REFERENCES

cian to the potential involvement of the legal process in the

patients outcome. Similarly, incontinence is a particularly Bannister, Sir Roger. (1992). Brain & Bannisters clinical neurology. Ox-

burdensome problem for caregivers and is associated with ford, UK: Oxford University Press.

higher rates of nursing home placement. Boyle, P. A., Grace, J., Zawacki, T. M., Ott, B. R., & Stout, J. C. (2001).

Frontal behavior change in neurodegenerative and acute neurologi-

Ratings may differ depending on features of the rater cal disorders. Manuscript submitted for publication.

and his or her relationship with the person being rated. In Cummings, J., Mega, M., Gray, K., Rosenberg-Thompson, S., Carusi, D.,

this sample, we did not systematically classify the type and & Gornbein, J. (1994). The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehen-

extent of the relationships between raters and the individu- sive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology, 44(12),

2308-2314.

als they rated. However, all raters considered themselves Finch, J. F., & West, F. G. (1997). The investigation of personality struc-

to be close family members or caregivers, and the majority ture: Statistical models. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4),

were cohabiting with the person whom they rated. None- 439-485.

Gorsuch, R. L. (1997). Exploratory factor analysis: Its role in item analy-

theless, some items may be too difficult for the caregiver or sis. Journal of Personality Assessment, 68, 532-560.

family member to rate because the items require informa- Grace, J., & Malloy, P. F. (2001). Frontal Systems Behavior Scale: Pro-

tion about the patients experience that is typically avail- fessional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources,

able only on self-reflection rather than by observation by Inc.

Grace, J., Stout, J., & Malloy, P. (1999). Assessing frontal behavior syn-

another individual (i.e., interest in sex, food has no taste or dromes with the Frontal Lobe Personality Scale. Assessment, 6(3),

smell, uses memory strategies). Finally, some items may 269-284.

have been ambiguous or confusing (i.e., apologizes for Hachinski, V. C., Iliff, L. D., Zilhka, E., Du Boulay, G. H., McAllister,

misbehavior), leading respondents to interpret the items V. L., Marshall, J., et al. (1975). Cerebral blood flow in dementia. Ar-

chives of Neurology, 32(9), 632-637.

differently than intended by the authors of the FrSBe. In Hoehn, M. M., & Yahr, M. D. (1967). Parkinsonism: Onset, progression

fact, idiosyncratic interpretation of items has been identi- and mortality. Neurology, 17, 427-442.

fied as a major source of discrepancy between self and in- Hulvershorn, L. A., Stout, J. C., Paulsen, J. S., & Siemers, E. (1999).

formant personality ratings (McCrae, Stone, Fagan, & Frontal neuropsychiatric syndromes in Huntingtons disease and Par-

kinsons disease [Abstract]. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology,

Costa, 1998). For several of the remaining items that did 14(1), 133.

not load highly on any of the factors, there does not appear Huntington Study Group. (1996). Unified Huntingtons Disease Rating

to be any systematic reason for their failure to load sa- Scale: Reliability and consistency. Movement Disorders, 11, 136-

142.

liently on their corresponding factor. These items simply Kertesz, A., Davidson, W., & Fox, H. (1997). Frontal Behavioral Inven-

may not have adequately captured the construct that they tory: Diagnostic criteria for frontal lobe dementia. Canadian Journal

were written to assess. of Neurological Sciences, 24, 29-36.

In summary, the results from the present study are con- Levin, J., Eisenberg, J., & Benton, A. (1991). Frontal lobe function and

dysfunction. New York: Oxford University Press.

sistent with the use of the FrSBe subscales in the assess- Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological assessment (3rd ed.). New

ment of behavioral disturbances associated with York: Oxford University Press.

neurological dysfunction. In addition, the item character- Lhermitte, F., Pillon, B., & Serdaru, M. (1986). Human autonomy and the

istics revealed by the factor analysis provide initial indica- frontal lobes. Part I: Imitation and utilization behavior: A

neuropsychological study of 75 patients. Annals of Neurology, 19(4),

tions regarding which items perform best in terms of the 326-334.

goals of the FrSBe. This exploratory factor analysis re- Lichter, D. G., & Cummings, J. L. (Eds.). (2001a). Frontal-subcortical

quires replication with confirmatory factor analysis to circuits in psychiatric and neurological disorders. New York:

Guilford.

avoid capitalization on chance findings (Finch & West,

Lichter, D. G., & Cummings, J. L. (2001b). Introduction and overview. In

1997). Such further studies are essential prior to any modi- D. G. Lichter & J. L. Cummings (Eds.), Frontal-subcortical circuits

fications in the use of the FrSBe, such as eliminating items. in psychiatric and neurological disorders (pp. 1-43). New York:

The finding of the three factors provides psychometric Guilford.

support for the subscale structure of the FrSBe and also

Downloaded from asm.sagepub.com at Afyon Kocatepe Universitesi on May 12, 2014

Stout et al. / FrSBe FACTOR ANALYSIS 85

Marin, R. S., Biedrzycki, R. C., & Firincioguliari, S. (1991). Reliability Stout, J. C., Wyman, M. F., Peavy, G. M., & Salmon, D. P. (2001). Frontal

and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res, 38, 143- neuropsychiatric symptoms in probable Alzheimers disease. Manu-

162. script submitted for publication.

McCrae, R. R., Stone, S. V., Fagan, P. J., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1998). Iden- Stuss, D., & Benson, D. (1986). The frontal lobes. New York: Raven.

tifying causes of disagreement between self-reports and spouse rat- Zawacki, T. M., Grace, J., Paul, R. H., Moser, D. J., Ott, B. R., Gordon,

ings of personality. Journal of Personality, 66, 285-313. N., et al. (2002). Impact of apathy on the prediction of functional abil-

McKhann, G., Drachman, D., Folstein, M., Katzman, R., Price, D., & ities of vascular dementia patients. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and

Stadlan, E. M. (1984). Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimers disease: Re- Clinical Neuroscience, 14, 296-302.

port of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of De-

partment of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimers.

Neurology, 34, 939-944. Julie C. Stout, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at Indiana Univer-

Mega, M., & Cummings, J. (1994). Frontal-subcortical circuits and neu- sity. Her research interests are in the area of basal ganglia and

ropsychiatric disorders. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical frontal diseases, especially Parkinsons and Huntingtons, and in

Neurosciences, 6(4), 38-70. drug abuse.

Norton, L., Malloy, P. F., & Salloway, S. (2001). The impact of behavioral

symptomology on activities of daily living in patients with dementia. Rebecca E. Ready, Ph.D., is a research fellow at Brown Univer-

American Journal of Geriatric Psychology, 9(1), 41-48.

sity. Her research focuses on neuropsychology and caregiving in

Paulsen, J. S., Ready, R. E., Stout, J. C., Salmon, D. P., Thal, L. J.,

Grant, I., & Jeste, D. V. (2000). Neurobehaviors and psychotic symp- dementia.

toms in Alzheimers disease. Journal of the International Neuro-

psychological Society, 6, 815-820. Janet Grace, Ph.D., is an associate professor at Brown Univer-

Paulsen, J. S., Stout, J. C., DeLaPena, J., Romero, R., Tawfik-Reedy, Z., sity. Her research interests include clinical neuropsychology, re-

Swenson, M. R., et al. (1996). Frontal behavioral syndromes in corti- habilitation, and frontal behavior disturbances.

cal and subcortical dementia. Assessment, 3(3), 327-337.

Ready, R. E., Stierman, L., & Paulsen, J. (2001). Ecological validity of Paul F. Malloy, Ph.D., is an associate professor at Brown Uni-

neuropsychological and personality measures of executive functions. versity. His research interests are in the field of frontal-

The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 15(3), 314-324.

subcortical brain systems, neuropsychology, and obsessive-

Reise, S., Waller, N., & Comrey, A. (2000). Factor analysis and scale re-

vision. Psychological Assessment, 12(3), 287-297. compulsive disorder.

Spreen, O., & Strauss, E. (1998). A compendium of neuropsychological

tests: Administration, norms, and commentary (2nd ed.). New York:

Jane S. Paulsen, Ph.D., is a professor at the University of Iowa.

Oxford University Press. Her research focuses on frontal-subcortical brain systems, Hun-

tingtons disease, and schizophrenia.

Downloaded from asm.sagepub.com at Afyon Kocatepe Universitesi on May 12, 2014

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Initial Clinical Assessment FormDocument10 pagesInitial Clinical Assessment FormOchee De Guzman CorpusPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- QBANKDocument38 pagesQBANKsbarolia2673% (11)

- Surgery QuestionsDocument312 pagesSurgery Questionsmonaliza7100% (9)

- Review Notes in Infection Control - NCLEXDocument1 pageReview Notes in Infection Control - NCLEXwyndz100% (10)

- NURSING CARE PLAN - Liver CirrhosisDocument2 pagesNURSING CARE PLAN - Liver Cirrhosisderic100% (27)

- Landau 1999Document10 pagesLandau 1999Gabriel Mercado InsignaresPas encore d'évaluation

- The Many Faces of Impulsivity PDFDocument8 pagesThe Many Faces of Impulsivity PDFGabriel Mercado InsignaresPas encore d'évaluation

- The Forms and Functions of Impulsive Actions: Implications For Behavioral Assessment and TherapyDocument19 pagesThe Forms and Functions of Impulsive Actions: Implications For Behavioral Assessment and TherapyGabriel Mercado InsignaresPas encore d'évaluation

- NIH Public Access: Behavioral Measures of Impulsivity and The LawDocument16 pagesNIH Public Access: Behavioral Measures of Impulsivity and The LawGabriel Mercado InsignaresPas encore d'évaluation

- 1088767908324430Document15 pages1088767908324430Gabriel Mercado InsignaresPas encore d'évaluation

- Watkins 1992Document53 pagesWatkins 1992Gabriel Mercado InsignaresPas encore d'évaluation

- Bartels 14 PHDDocument222 pagesBartels 14 PHDGabriel Mercado InsignaresPas encore d'évaluation

- Caluschi MarianaDocument5 pagesCaluschi MarianaGabriel Mercado InsignaresPas encore d'évaluation

- The Endocrinopathies of Anorexia NervosaDocument13 pagesThe Endocrinopathies of Anorexia NervosaCarla MesquitaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2004 4050B1 14 Fosinopril Label PedsDocument23 pages2004 4050B1 14 Fosinopril Label PedsМаргарет ВејдPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Causes of BlindnessDocument58 pagesCommon Causes of BlindnesskaunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Harbinger of The Vicious Cycle of DiabetesDocument21 pagesGestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Harbinger of The Vicious Cycle of DiabetesEmma Lyn SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 11 Role of Fungi in Human Welfare: ObjectivesDocument12 pagesUnit 11 Role of Fungi in Human Welfare: Objectivessivaram888Pas encore d'évaluation

- Common Pulmonary Diseases: Emmanuel R. Kasilag, MD, FPCP, FPCCPDocument74 pagesCommon Pulmonary Diseases: Emmanuel R. Kasilag, MD, FPCP, FPCCPDivine Grace FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal TinitusDocument14 pagesJurnal TinitusAndriyani YaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Castle Connolly Graduate Board Review SeriesDocument63 pagesCastle Connolly Graduate Board Review SeriesCCGMPPas encore d'évaluation

- Atkinson R L - Weight CyclingDocument7 pagesAtkinson R L - Weight CyclingmaddafackerPas encore d'évaluation

- DesenteryDocument3 pagesDesenteryAby Gift AnnPas encore d'évaluation

- The Mental and Sexual DisordersDocument5 pagesThe Mental and Sexual DisordersGrace BrionesPas encore d'évaluation

- Approach To The Infant or Child With Nausea and Vomiting - UpToDateDocument47 pagesApproach To The Infant or Child With Nausea and Vomiting - UpToDatemayteveronica1000Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lung FlukesDocument23 pagesLung FlukesGelli LebinPas encore d'évaluation

- Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) - Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentDocument10 pagesChronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) - Causes, Symptoms, Treatmentnurul auliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Flow ChartDocument8 pagesDiabetes Flow ChartNicky ChhajwaniPas encore d'évaluation

- HistoryDocument3 pagesHistoryJennesse May Guiao IbayPas encore d'évaluation

- Racelis Vs United Philippine LinesDocument1 pageRacelis Vs United Philippine LinesEarvin Joseph BaracePas encore d'évaluation

- StomatitisDocument3 pagesStomatitiswidya RDPas encore d'évaluation

- Care For Your Heart While You SleepDocument6 pagesCare For Your Heart While You SleepkrishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Radiology DVTDocument90 pagesRadiology DVTDhruv KushwahaPas encore d'évaluation

- Proceedings of BUU Conference 2012Document693 pagesProceedings of BUU Conference 2012Preecha SakarungPas encore d'évaluation

- Esmr 2Document1 pageEsmr 2Martina FitriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Appendicitis (History & Examination)Document6 pagesAppendicitis (History & Examination)Doctor Saleem Rehman75% (4)

- Undo It!: How Simple Lifestyle Changes Can Reverse Most Chronic Diseases - Dean Ornish M.D.Document5 pagesUndo It!: How Simple Lifestyle Changes Can Reverse Most Chronic Diseases - Dean Ornish M.D.besahahu7% (15)

- Onychauxis or HypertrophyDocument3 pagesOnychauxis or HypertrophyKathleen BazarPas encore d'évaluation

- Covered Diagnoses & Crosswalk of DSM-IV Codes To ICD-9-CM CodesDocument12 pagesCovered Diagnoses & Crosswalk of DSM-IV Codes To ICD-9-CM CodesAnonymous 1EQutBPas encore d'évaluation