Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

(Homo) Eroticism and Calixthe Beyala, by Sybille Ngo Nyeck, On Witness Mag.

Transféré par

IRNwebTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

(Homo) Eroticism and Calixthe Beyala, by Sybille Ngo Nyeck, On Witness Mag.

Transféré par

IRNwebDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

http://www.thewitness.org/article.php?

id=190

(Homo)eroticism and Calixthe Beyala

By Sybille Ngo Nyeck

Cameroonian writer Calixthe Beyala's recent novel, Femme nue Femmes noire

(Naked Woman Black Woman, Albin Michel, 2003), continues the author's prolific career

since she first published C'est le soleil qui m'a bûlé (1987). Femme nue Femme noire is

Calixthe Beyala's first erotic novel, an audacity that has won her many critics as well as

admirers. Fully aware of the fact that in "Africa, eroticism does exist even though it is not

named as such" (see this reference) Femme nue Femme noire puts an end to the muteness

assigned to women's bodies.

"To understand how women become pregnant, because in our world, some words

are nonexistent" is Irene Fofo's primary goal as the main character of this novel. After

waiting for 15 years, she finally frees herself from the grip of a mother who is too

worried about "the blood that flows between her legs." But Irene's spirit is just as

energetic as her menstrual flow. On a morning when the sky seems to be incredibly

undisturbed, Irene decides to leave the insular world of her mother for a journey that is to

help her name the unnamed sex and to devour it until ecstasy.

On the quay, she makes herself an explorer; a detector of "things that are not

given [to me] . . .domains inaccessible to ordinary miracles." In the midst of men's voices

and children's cries, Irene detects the object of her dreams: a bag "laying between the legs

of a woman." Unfortunately for Irene, what she has happily discovered is not a man.

In her escape, angry men denounce Irene using the masculine "Au voleur! Au

voleur!" (Oh robber! Oh robber!). Irene is actually accused of stealing the dead baby's

body: a crime that could send her to jail for the rest of her life, or, indeed, to the mortuary.

©2004 by Sybille Ngo Nyeck

The society believes that Irene's behavior puts her in the ranks of the "burning-women"

killers or the robbers of men's bags (bursa), and by extension their paternity/virility. Irene

is one of these "women-husbands" whose sexual desires kindle men's fears, and, worse,

their inquisitorial zeal. Her crime of "outrage against paternity" makes her eligible to join

the sorority of witches who challenge the "circles of fire" until she vanishes into exile.

She takes refuge in a Negro-Muslim neighborhood "unknown to her" where

women "speak to one another with warm words" despite the violence and inequalities

exhibited in the surrounding "social comedy." Once in this marshy little town, Irene

pretends to be a wealthy heiress as a mantel in the face of poverty. But "innocence as

good manners is nothing but deceit." She fornicates with the "unknown" while

"pretending to move forward in the furnace of this sleepy town" she hates.

Irene is not fond of ruins. The lifeless colors of the city leave her breathless,

similar to her lack of emotions for the men in her life. In sum, Irene "understands [the

posturing of different characters] . . . but disapproves" of their hypocrisy; showing

difference by her indifference. "Here, the ugliness, sublimated by human intelligence,

explodes under the sky of a cataclysmic disorder."

In her exile, Irene forgets the hierarchical settings of sexual roles. She is lost in

her frolics with Ousmane under a mango tree. Then with Fatou (Ousmane's wife) both

women tune in to their respective secret frequencies "as long distance radio stations

intercept hazardously by thick nights" until they extract from their bodies "the last juices

of inhibition." But it is difficult for two women, even in the closet, to really be alone.

Neither the bedrooms nor the newspapers are willing to hide them for long or to protect

them from the sex police. There are too many unforeseen obstacles; too many injunctions

to "change direction" or to be strangled by the terrifying shadows of the police.

Although many men, both fictional and real, appear in Irene's erotic, empiric

universe, only Fatou feeds her with love. Both women discuss childbearing, but maternity

is not the only focus of their lives. Sexuality in Femme nue Femme noire is jauntily

unproductive and magisterially creative. As an example, the levirate [the law by which a

©2004 by Sybille Ngo Nyeck

man marries his brother's widow] imprisons grandmothers as bedfellows for younger

males but even in an "artificial situation" like this, the "withered old women" reinvent

their relationships in pro-creative and re-creative dimensions.

Calixthe Beyala's female characters are far from being egg-laying chickens.

Libidinous women, they form a web of mixed desires. Fatou offers to Irene a "roof"; an

intimate but open space for both sexual and political activism; denunciation and

reconciliation. They create a space to navigate men's fancies and speculations, each one

featuring his portion of indifference.

Through poetic writing, Calixthe Beyala undresses the mechanical sexuality of

false modesty and the status quo and transforms it into political eroticism. Beyala's

engagé eroticism is a collective movement of submissions and withdrawals, revolts and

coups, in which orgies rebel against the monopoly and other forms of privatization and

abject domestication. Women's bodies are invested with innate rights.

When Irene couples with Eva (Hayatou's wife) in a homosexual union, it is

formed to resist the destructive forces that "suck" the vital energies that empower

creativity. Be it global or local, eroticism for the sake of egoistic pleasure is immoral. In a

mystical embrace, Irene and Eva cross and uncross the knots of abstinence until new

visions are born in their nude bodies; a "heavenly music [that only they can]

understand . . .a woman . . .the elixir against death." For Irene and Eva, "the sun has not

yet set." There is enough light for the seeds of freedom to bloom when resignation and

resistance kiss each other.

However, it is important to notice that Femme nue Femme noire is not about

sexual identities. Sexuality here "is not an idea to debate, a law to parley, a scarecrow to

agitate, an insanity to protest against or simulate on TV screens." According to one

character, sex is not where to find a "sense of orientation." Sexuality is liberated of any

orientation and expectation. It is naked and terrifically creative. However, this

metamorphosis is not yet beneficial to women nor to their fetuses, which are merely

viewed as commodities. Eva becomes pregnant but never delivers her baby.

©2004 by Sybille Ngo Nyeck

Far from prescribing, Beyala describes what is simply mimed in the heart of her native

equatorial forest. By deconstructing the categories, she also deconstructs the agents and

their fields of action. The characters are never static: "Ousmane holds a chicken that he

sodomized as if it was a woman."

The black woman in the image of Africa is a naked woman; the pre-colonial

woman of ever-present dreams. A woman's desires, however, are still censored on the

"Black Continent." Africa is a house where no one "supports the cries of pleasures of

women."

At 16, when Irene decides to return to her mother, she is fully aware of the

dangers ahead. She wants to "remain mistress of her skin" because of the threat of being

sold on the "matrimonial" markets where women are viewed as 'congélés' (**). These

purchased marriages are problematic, as many don't last and women are "recycled" on the

market. Irene's return home exhibits her willingness to break the vicious circle of denial

of the vice in this formal and informal industry.

These traditional and modern markets are growing, thanks in part to the World

Bank's development-related "restrictions" that negatively affect the representations of

women's bodies. This is especially true in Africa where war is becoming the biggest

employer of all. How are we going to break the powerful "norm" of national and global

dictatorships that successfully manage to tax the impoverished? With whom are we going

to "blow up his buttons, his zippers, his belts, all that is dear to man and gives him a

complex of superiority" but not security? Considering the cultural, economic, political

nudities and the growth of insecurity, Irene Fofo suggests a therapy of a "shared

pleasure." She and her same-sex partners create a new way of relating to the socio-

cultural, the economic, the political, and the religious.

This is a noble dream, but a difficult one to fulfill for a black woman who knows

that her destiny "is decided there, in the hands of men who carry iron's bars." Irene

succeeds in her adventurous life to undress some men but disarms none. Battered and

abandoned at a corner of a route, her clothes are torn up by her aggressors, as was the

©2004 by Sybille Ngo Nyeck

robe of Christ. She is left naked with only her skin as a garment and her congealed blood

as its color. "Help! Please help me!" cries Irene's mother, who wants her daughter to

come back to life. Please, if you hear her crying, help save Irene from dying. We have so

much to learn from her.

Notes:

* The book reviewed here is not yet translated into English. All of the translations in the following article

are my own.

** 'Congélé' is a Cameroonian slang word to designate second-hand merchandise imported from Europe.

The 'congélé' (frozen) is a commodity that loses its sensibility. The 'congélé' verbalizes the anti-social and

anti-(real and sustainable) development processes and actions that keep the global South economically

dependent on the North. The 'congélé' (cold) occupies a lot of space and melts under the fire (sun) of Africa

without leaving a souvenir. So, indeed, are women melting under patriarchy. This is because they are

"recycled" and treated in commercial and sexist ways.

First published by The Witness (www.thewitness.org), January 29, 2004.

©2004 by Sybille Ngo Nyeck

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas Has Many Different Messages Throughout The Story and Evil Is Hidden Within This StoryDocument2 pagesThe Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas Has Many Different Messages Throughout The Story and Evil Is Hidden Within This Storyapi-242538912Pas encore d'évaluation

- Things Fall Apart Role of WomanDocument4 pagesThings Fall Apart Role of WomanHafiz Ahmed100% (1)

- Descendants of the Ebony Path: A Tale of the 12 Risen, Book One UnrestD'EverandDescendants of the Ebony Path: A Tale of the 12 Risen, Book One UnrestPas encore d'évaluation

- Aphra Behns The Rover A Pertinent ModernDocument5 pagesAphra Behns The Rover A Pertinent Modernaditya gogoiPas encore d'évaluation

- PoetryDocument16 pagesPoetryRitam GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Feuille D'albumDocument3 pagesFeuille D'albumAndreea SimonPas encore d'évaluation

- A Dance of The ForestDocument11 pagesA Dance of The ForestAnkita KaliramanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rhetorical Analysis AssignmentDocument7 pagesRhetorical Analysis Assignmentapi-460455366Pas encore d'évaluation

- Yerma: Full Text and Introduction (NHB Drama Classics)D'EverandYerma: Full Text and Introduction (NHB Drama Classics)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bride PriceDocument12 pagesBride PriceGabiPas encore d'évaluation

- Elisabeth Von Samsonow. Anti-ElectraDocument52 pagesElisabeth Von Samsonow. Anti-ElectraMaria Eduarda ChecaPas encore d'évaluation

- All Out: The No-Longer-Secret Stories Of Queer Teens Throughout The AgesD'EverandAll Out: The No-Longer-Secret Stories Of Queer Teens Throughout The AgesÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2)

- Henrik Johan IbsenDocument2 pagesHenrik Johan IbsenMrinmoyee MannaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender RoleDocument2 pagesGender Roleavishek sahaPas encore d'évaluation

- In Favor of the Sensitive Man: And Other EssaysD'EverandIn Favor of the Sensitive Man: And Other EssaysÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Ports of Call by Amin Maalouf (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideD'EverandPorts of Call by Amin Maalouf (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuidePas encore d'évaluation

- Feminism and Ibsen's A Doll's HouseDocument7 pagesFeminism and Ibsen's A Doll's HouseSamy Ismail100% (1)

- Bac Llce Oral ChiaraDocument5 pagesBac Llce Oral ChiaraDominique KamaPas encore d'évaluation

- American Greed and Poverty Assunta Kent: and What of The Night?: Fornes' Apocalyptic Vision ofDocument16 pagesAmerican Greed and Poverty Assunta Kent: and What of The Night?: Fornes' Apocalyptic Vision ofAksharaPas encore d'évaluation

- Feminist Themes in A Literary FormDocument2 pagesFeminist Themes in A Literary FormhPas encore d'évaluation

- Pan S Labyrinth El Laberinto Del Fauno RDocument12 pagesPan S Labyrinth El Laberinto Del Fauno Rkivanc.ermanPas encore d'évaluation

- Henrik IbsenDocument3 pagesHenrik IbsenNimra SafdarPas encore d'évaluation

- A Game of ChessDocument19 pagesA Game of ChessJl WinterPas encore d'évaluation

- Wole Soyinka - Death and The King's HorsemanDocument6 pagesWole Soyinka - Death and The King's HorsemantarsilapassosPas encore d'évaluation

- Feminism PurpleDocument11 pagesFeminism PurpleDidi Gump EddiePas encore d'évaluation

- The Years by Virginia Woolf (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideD'EverandThe Years by Virginia Woolf (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuidePas encore d'évaluation

- The Curse of Zainab, Pharaonic Blood: Son of Chaos, #3D'EverandThe Curse of Zainab, Pharaonic Blood: Son of Chaos, #3Pas encore d'évaluation

- James Joyce - DublinersDocument8 pagesJames Joyce - DublinersEnđ RiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sexualities and Social Life in SpainDocument1 pageSexualities and Social Life in SpainIRNwebPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 Sexualities and Science in Eastern EuropeDocument3 pages11 Sexualities and Science in Eastern EuropeIRNwebPas encore d'évaluation

- The Status of Sexual Diversity in Islam TodayDocument8 pagesThe Status of Sexual Diversity in Islam TodayIRNweb0% (1)

- IRN News 2010 SpringDocument2 pagesIRN News 2010 SpringIRNwebPas encore d'évaluation

- CFP: LGBT Activism in Eastern Europe - Sextures 3rd IssueDocument2 pagesCFP: LGBT Activism in Eastern Europe - Sextures 3rd IssueIRNwebPas encore d'évaluation

- Sephis Codes Ia Ext Wkshop 2010Document2 pagesSephis Codes Ia Ext Wkshop 2010IRNwebPas encore d'évaluation

- Transnational LGBTQ Organizing in The World and On The Web - International Resource Network's One-Day SymposiumDocument1 pageTransnational LGBTQ Organizing in The World and On The Web - International Resource Network's One-Day SymposiumIRNwebPas encore d'évaluation

- IRN 2009 FallDocument1 pageIRN 2009 FallIRNwebPas encore d'évaluation

- IRN Symposium FINALDocument1 pageIRN Symposium FINALIRNwebPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Studies Project For Year 4Document20 pagesSocial Studies Project For Year 4Leena Hmk100% (1)

- Randell James D. Manjarres: UPS - Under Preventive Suspension (Counted Incl. of Saturdays, Sundays & Holidays)Document21 pagesRandell James D. Manjarres: UPS - Under Preventive Suspension (Counted Incl. of Saturdays, Sundays & Holidays)Randell ManjarresPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Preschool Registration FormDocument4 pagesSample Preschool Registration FormSir CalaqueiPas encore d'évaluation

- Tracing Roots Genealogy WorkbookDocument20 pagesTracing Roots Genealogy Workbookveronica.h.recipethisPas encore d'évaluation

- FNCPDocument18 pagesFNCPLyzahearts100% (1)

- Beatles-While My Guitar Gently WeepsDocument1 pageBeatles-While My Guitar Gently WeepsMárcio O BorgesPas encore d'évaluation

- Checklist of Requirements For Municipal MeetDocument1 pageChecklist of Requirements For Municipal MeetKhrizzle Agsalon-VinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lee Harvey Oswald and The Blanket, The Bag and The RifleDocument70 pagesLee Harvey Oswald and The Blanket, The Bag and The RifleJudyth Vary Baker100% (2)

- Ten Shades of Sexy A Free Sampler Collection PDFDocument96 pagesTen Shades of Sexy A Free Sampler Collection PDFMichael GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Empire S First Seljuk Erisgen-ChrysoDocument5 pagesThe Empire S First Seljuk Erisgen-ChrysoNuma BuchsPas encore d'évaluation

- Colonel James Duncan, Clan Duncan Society - Scotland UKDocument2 pagesColonel James Duncan, Clan Duncan Society - Scotland UKEUTOPÍA MÉXICOPas encore d'évaluation

- Goldfish StoryDocument5 pagesGoldfish StoryAsareer TubePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1Document56 pagesChapter 1Vea CamillePas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesReflection PaperShailah Leilene Arce BrionesPas encore d'évaluation

- Adopting An Unrecognized Illegitimate ChildDocument2 pagesAdopting An Unrecognized Illegitimate Childyurets929Pas encore d'évaluation

- Emergent Women, Emergent TextDocument16 pagesEmergent Women, Emergent TextSanaa MughalPas encore d'évaluation

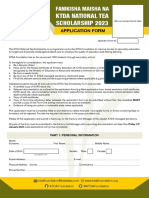

- KTDA Foundation 2023 Application Form 1 1Document5 pagesKTDA Foundation 2023 Application Form 1 1johnny muhatiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Degas PDFDocument12 pagesDegas PDFUna Djordjevic50% (2)

- Princess Diana Work in PairsDocument3 pagesPrincess Diana Work in PairsDaniela SalgadoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Wedding Dance by Amador Daguio Is A Story of Husband and WifeDocument1 pageThe Wedding Dance by Amador Daguio Is A Story of Husband and Wifeleana nhalie100% (1)

- Petition For GuardianshipDocument3 pagesPetition For GuardianshipFara TaradjiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Two Gentlemen of VeronaDocument37 pagesThe Two Gentlemen of VeronachindubgirijanPas encore d'évaluation

- Taking Care of Ron WeasleyDocument5 pagesTaking Care of Ron WeasleyBianka PötördiPas encore d'évaluation

- NYC Family Court DocketDocument1 pageNYC Family Court DocketCity Limits (New York)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Acknowledgement: Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University LucknowDocument21 pagesAcknowledgement: Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University Lucknowsakshi barfalPas encore d'évaluation

- Jane EyreDocument131 pagesJane Eyreadariadna100% (5)

- AICE Sociology As Level Summer 2016 WorkDocument3 pagesAICE Sociology As Level Summer 2016 WorkSashaPas encore d'évaluation

- Familyworksheet Reading Compreh PDFDocument3 pagesFamilyworksheet Reading Compreh PDFJuli VelazquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Forbidden Desire - Jordan SilverDocument156 pagesForbidden Desire - Jordan SilverNicoleta Mihai50% (4)