Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Essay 2 Wuttivat Sabmeethavorn 835133 PDF

Transféré par

Que SabTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Essay 2 Wuttivat Sabmeethavorn 835133 PDF

Transféré par

Que SabDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Proof of an External World?

By raising his hands, G.E. Moore claims to have proven the existence of an

external world in his Proof of an External World. This proof, he claims, satisfies

three necessary conditions for a rigorous proof. I will explain the proof and its

necessary conditions which Moore claims are satisfied. Subsequently, I will

critically evaluate Moores arguments for the proof satisfying these conditions, and

how the Cartesian sceptic might response to this. Consequently, I will argue that

Moores proof is not a convincing proof of the external world, that is does not provide

a compelling response to the Cartesian sceptic, and that Moore does indeed beg the

question again the Cartesian sceptic.

I will briefly explain G.E. Moores proof and his three conditions for a

rigorous proof. Basically, Moores proof of an external world is as follows:

(P1): If hands exist, there exists an external world.

(P2): Here is one hand, and here is another.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(C): Therefore, there exists an external world (Moore, 1993, p. 166).

He claims this to be a rigorous proof because it satisfies these three conditions:

(1): The premise must be different from the conclusion.

(2): The premise must be known to be true.

(3): The conclusion must follow from the premise (Moore, 1993, p. 166).

835133 Wuttivat Sabmeethavorn Page | 1

The conditions Moore provides are important to him because the conditions justify

his proof as being perfectly rigorous, and that a better or more rigorous proof cannot

be given (Moore, 1993, p. 166).

I will now critically evaluate Moores arguments for the proof satisfying these

conditions, and how the Cartesian sceptic might respond to this. I think that

condition (3) is good because it makes a proof valid. Moore argues that his proof

meets condition (3). He claims that if he were to change his premise to here is one

hand and here is another now, then it follows that there are two hands in existence

now (Moore, 1993, p. 167). It seems here that the Cartesian sceptic would not be

able to respond because Moores proof does appear to satisfy (3) (C) does follow on

from (P1) and (P2).

I think that condition (2) is also good because it makes a proof sound as (2)

states the truth of the premise is required. Moore further claims that his proof

satisfies (2) by arguing that he knows (P2) to be true and says that it would be

absurd to suggest that I did not know it, but only believed it (Moore, 1993, p.

166). The Cartesian sceptic could ask how does he actually know (P2)? And proceed

to refute by providing the following modus ponens argument:

(P1): If I cannot tell the difference between waking and dreaming,

then I cannot be sure that I have two hands.

(P2): I cannot tell the difference between waking and dreaming.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(C): Therefore, I cannot be sure that I have two hands (Preston, 2004).

835133 Wuttivat Sabmeethavorn Page | 2

Moore later concedes to this because he says in his paper that even though he has

conclusive evidence that he is awake, this is a very different thing from being

able to prove it (Moore, 1993, p. 169). However, Moore could respond to the

Cartesian sceptic by changing the modus ponens argument to a modus tollens

argument whilst keeping (P1) the same. This is called the Moore shift and appears

as:

(P1): If I cannot tell the difference between waking and dreaming,

then I cannot be sure that I have two hands.

(P2): Im sure that I have two hands.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(C): Therefore, I can tell the difference between waking and dreaming

(Preston, 2004).

Both arguments are valid because the conclusion follows logically from the

premises. However, only one of these arguments can be sound because if one

premise for example (P2) is true, the other (P2) must be false. Moore would

suggest that we would have more reason to believe in (P2) than in (P2) because

(P2) seems more plausible than the plausibility of hyperbolic doubt that we are

dreaming right now or being controlled by an evil demon a method Cartesian

sceptics use to prove (P2) (Preston, 2004). This comparative plausibility, I think,

gives Moores proof some weight, but ultimately means that condition (2) is

unsatisfied because Moore concedes to not being able to prove that he knows (P2) to

be true.

835133 Wuttivat Sabmeethavorn Page | 3

For condition (1), I think that this condition allows for a premise to be

different from a conclusion, but still presuppose the conclusion. Condition (1)

therefore will make the proof less convincing because begging the question doesnt

further the proof. Moore argues that his proof satisfies (1) because his premise is

more specific than his conclusion (Moore, 1993, p. 166). Which is correct, (P1) and

(P2) are more specific than, and different to (C). Hence, (1) is satisfied. However, the

problem with (1), the Cartesian sceptic may argue, is there are examples which

meet condition (1) but seem to beg the question. Take the example here:

(P1): If writing essays is fun, philosophy is fun!

(P2): Writing essays is fun.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

(C): Philosophy is fun!

Clearly, this meets condition (1) because (P1) and (P2) are more specific and

different from (C). However, it seems that this argument begs the question

because the statement philosophy is fun is in both (P1) and (C). It seems like

both this example, and Moores proof presuppose the conclusion in the premise.

I will argue why Moores proof is not a convincing proof. It could be argued

that Moore is not trying prove his knowledge of the existence of the external world,

but rather, he is trying to prove the existence of an external world (Baldwin, 2010).

That means that (P2) is simply just known, meaning condition (2) is satisfied.

However, this does not make it a convincing proof of the external world. This is

because he still presupposes (C) in (P1), even though (2) is met and the proof is

835133 Wuttivat Sabmeethavorn Page | 4

sound and valid. By doing so, the proof isnt furthered in any way. Therefore,

Moores proof is not a convincing proof of the external world.

Finally, I will argue that this proof is not a compelling response to the

Cartesian sceptic, and that he does indeed beg the question against the Cartesian

sceptic. I do not think Moores proof is a compelling response to the Cartesian

sceptic because in the Moore shift, the factor that determines which premise is more

plausible is intuition. That is, a person such as a Cartesian sceptic could find

more reason to believe in the plausibility of (P2) than that of (P2). For a Cartesian

sceptic, this is already intuitively more plausible as they take hyperbolic doubt

seriously. Hence, this is not a compelling response because it will not change the

Cartesian sceptics view. Even if we accept that (P2) is true, there still exists the

problem of (P1) presupposing (C), which ultimately means that Moore does indeed

beg the question against the Cartesian sceptic.

This essay has explained Moores proof of an external world and the

conditions he presents that make his proof a rigorous proof. I have critically

evaluated Moores arguments for the proof satisfying these conditions, and how the

Cartesian sceptic might response to this. I therefore conclude through my

evaluation, that Moores proof is not a convincing proof of an external world, that it

does not provide a compelling response to the Cartesian sceptic and Moore does

indeed beg the question against the Cartesian sceptic.

835133 Wuttivat Sabmeethavorn Page | 5

References

Baldwin, T. (2010). George Edward Moore. (E. N. Zalta, Editor) Retrieved April 24,

2016, from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moore/

Moore, G. E. (1993). Proof of an External World. In T. Baldwin, G. E. Moore Selected

Writings (pp. 147-170). London: Routledge.

Preston, A. (2004). George Edward Moore (18731958). Retrieved April 25, 2016,

from Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

http://www.iep.utm.edu/moore/#SH2d

835133 Wuttivat Sabmeethavorn Page | 6

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- PHL/410 Classical Logic Post Test CH 4Document6 pagesPHL/410 Classical Logic Post Test CH 4Hurricane2010100% (2)

- BIOL10002 Sample ExamDocument21 pagesBIOL10002 Sample ExamQue Sab100% (2)

- 1H Legal Technique Reviewer Legal Logic by Evangelista and Aquino 2015Document29 pages1H Legal Technique Reviewer Legal Logic by Evangelista and Aquino 2015Rex GodMode88% (8)

- Economics of McDonaldsDocument13 pagesEconomics of McDonaldsQue Sab100% (2)

- Pre-Test - Introduction To PhilosophyDocument4 pagesPre-Test - Introduction To PhilosophyCaroline SolomonPas encore d'évaluation

- PHL/410 Classical Logic Pre-Test CH 4Document6 pagesPHL/410 Classical Logic Pre-Test CH 4Hurricane2010100% (1)

- Logical Fallacies - I & II REVISIONDocument78 pagesLogical Fallacies - I & II REVISIONkeyurshah38Pas encore d'évaluation

- Moore's Proof of An External WorldDocument5 pagesMoore's Proof of An External Worldmackus28397Pas encore d'évaluation

- Unit I: Moore's Response To Skepticism: January 6, 2004Document4 pagesUnit I: Moore's Response To Skepticism: January 6, 2004Sajal MondalPas encore d'évaluation

- De-On Moores Notion of ProofDocument10 pagesDe-On Moores Notion of ProofAVANISH MISHRAPas encore d'évaluation

- Antiscepticism MooreDocument19 pagesAntiscepticism Moorealexandrac85Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Common Sense-Daly-2010Document23 pages1 Common Sense-Daly-2010joshka musicPas encore d'évaluation

- Dogmatism Without Mooreanism: Jonathan FuquaDocument22 pagesDogmatism Without Mooreanism: Jonathan Fuqualastname namePas encore d'évaluation

- Dialnet RespuestasAMisCriticos 4852602Document22 pagesDialnet RespuestasAMisCriticos 4852602Patricio Y CPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Sense PDFDocument10 pagesCommon Sense PDFrizwanPas encore d'évaluation

- MacFarlane's Truth RelativismDocument13 pagesMacFarlane's Truth RelativismGavin MrphyPas encore d'évaluation

- Warrant Entails TruthDocument22 pagesWarrant Entails TruthSimón Palacios BriffaultPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Thinkin1Document10 pagesCritical Thinkin1Tan Yan TingPas encore d'évaluation

- Formative WorkDocument4 pagesFormative WorkRuyi ShiPas encore d'évaluation

- On G. E. Moore's 'Proof of An External World'Document18 pagesOn G. E. Moore's 'Proof of An External World'mckavanagh1Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Brief Introduction To ArgumentsDocument7 pagesA Brief Introduction To ArgumentsJohn DarwinPas encore d'évaluation

- Putnam, Three Valued-LogicDocument9 pagesPutnam, Three Valued-LogicCarlos CaorsiPas encore d'évaluation

- Stroud's "The Problem of The External World"Document19 pagesStroud's "The Problem of The External World"Aditya TripathiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Simulation Argument FAQDocument4 pagesThe Simulation Argument FAQScarman21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Barnes-The Law of ContradictionDocument9 pagesBarnes-The Law of ContradictionOscar Leandro González RuizPas encore d'évaluation

- Puzzles and ParadoxesDocument3 pagesPuzzles and ParadoxeskhubaibPas encore d'évaluation

- Abstract:: Numerical Quantification and Temporal Intervals: A Span-Er in The Works For Presentism?Document11 pagesAbstract:: Numerical Quantification and Temporal Intervals: A Span-Er in The Works For Presentism?Jonathon J. Andrew MuñozPas encore d'évaluation

- Initial Discussion PostDocument4 pagesInitial Discussion Postapi-279531152Pas encore d'évaluation

- D Wop Age ProofsDocument14 pagesD Wop Age Proofsemonahsanul007Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reading. Moore. A Defence of Common SenseDocument4 pagesReading. Moore. A Defence of Common Sensealysa.leemynnPas encore d'évaluation

- Phin 12232Document8 pagesPhin 12232tang jimPas encore d'évaluation

- 2012 Pruss Sincerely Asserting What You Do Not BelieveDocument7 pages2012 Pruss Sincerely Asserting What You Do Not Believeoskar lindblom (snoski)Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Third Route To The Doomsday Argument: 1. The Carter-Leslie ViewDocument14 pagesA Third Route To The Doomsday Argument: 1. The Carter-Leslie View1c2r3sPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Evaluating ArgumentsDocument6 pages1 Evaluating ArgumentsxyrylsiaoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Third Route To Doomsday ArgumentDocument15 pagesA Third Route To Doomsday ArgumentnovriadyPas encore d'évaluation

- Defeasibility in LawDocument23 pagesDefeasibility in LawmarcelolimaguerraPas encore d'évaluation

- Logic in LDDocument42 pagesLogic in LDChris ElkinsPas encore d'évaluation

- Proof of An External WorldDocument3 pagesProof of An External WorldFarri93Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dudman (1992) A Popular Presumption RefutedDocument2 pagesDudman (1992) A Popular Presumption RefutedbrunellusPas encore d'évaluation

- What If Anything Can We KnowDocument6 pagesWhat If Anything Can We KnowGene Val Levitsky100% (1)

- Skepticism About TruthDocument3 pagesSkepticism About TruthHoward MokPas encore d'évaluation

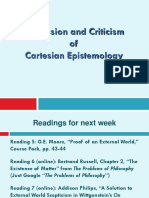

- Discussion and Criticism of Cartesian EpistemologyDocument65 pagesDiscussion and Criticism of Cartesian EpistemologyStephen AlaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Theories of Uncertainty (Smets, 1999)Document14 pagesTheories of Uncertainty (Smets, 1999)GabrielpenquistoPas encore d'évaluation

- Alter Egos and Their NamesDocument22 pagesAlter Egos and Their NamesMoe PollackPas encore d'évaluation

- Cambridge University PressDocument12 pagesCambridge University PressRayan Ben YoussefPas encore d'évaluation

- Tan & Crawford-What Is KnowledgeDocument9 pagesTan & Crawford-What Is KnowledgeGladys LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Refutations of The Simulation ArgumentDocument8 pagesRefutations of The Simulation ArgumentAnthony ReyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Theory of EvidenceDocument5 pagesThe Theory of EvidenceLukas NabergallPas encore d'évaluation

- HepDocument10 pagesHepAMan HasNoNamePas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 4 Standards For Evaluation and Types of ArgumentsDocument36 pagesLecture 4 Standards For Evaluation and Types of Argumentssin leePas encore d'évaluation

- Are Philosophical Zombies Possible?Document4 pagesAre Philosophical Zombies Possible?Matt BlewittPas encore d'évaluation

- Unger Xyz HegolinoDocument10 pagesUnger Xyz HegolinoRaminIsmailoffPas encore d'évaluation

- Phil SC CH 2Document22 pagesPhil SC CH 2eyukaleb4Pas encore d'évaluation

- General Philosophy - InductionDocument4 pagesGeneral Philosophy - InductionParin SiddharthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Is There Anything at All? 101Document1 pageWhy Is There Anything at All? 101CherryPas encore d'évaluation

- Truth in Epistemology, Epistemic vs. Non-EpistemicDocument10 pagesTruth in Epistemology, Epistemic vs. Non-EpistemicClarisse ThomasPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Reviews The Philosophical Review, Vol. 114, No. 1 (January 2005)Document4 pagesBook Reviews The Philosophical Review, Vol. 114, No. 1 (January 2005)roland_lasingerPas encore d'évaluation

- Affirming A Straw Man: A Reply To BowlesDocument10 pagesAffirming A Straw Man: A Reply To BowlesDaniel CabralPas encore d'évaluation

- Psilos - Lecture Notes Philosophy of Science (LSE)Document98 pagesPsilos - Lecture Notes Philosophy of Science (LSE)Krisztián PetePas encore d'évaluation

- A Brief Introduction To Logic and ArgumentationDocument26 pagesA Brief Introduction To Logic and ArgumentationErida PriftiPas encore d'évaluation

- Theoria Volume 74 Issue 2 2008 (Doi 10.1111 - j.1755-2567.2008.00011.x) JACOB BUSCH - No New Miracles, Same Old TricksDocument13 pagesTheoria Volume 74 Issue 2 2008 (Doi 10.1111 - j.1755-2567.2008.00011.x) JACOB BUSCH - No New Miracles, Same Old TricksVladDolghiPas encore d'évaluation

- Bonjour's A Priori Justification of InductionDocument10 pagesBonjour's A Priori Justification of Inductionראול אפונטהPas encore d'évaluation

- Armstrong 1991Document11 pagesArmstrong 1991rkasturiPas encore d'évaluation

- BL Unit 5 ReadingsDocument4 pagesBL Unit 5 ReadingsglcpaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tripartite Theory of KnowledgeDocument5 pagesTripartite Theory of KnowledgeThomasMcAllisterPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 - ArgumentsDocument15 pages2 - Argumentshealth worldPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary Of "Falsificationism As A Criterion For Scientific Demarcation" By Karl Popper: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESD'EverandSummary Of "Falsificationism As A Criterion For Scientific Demarcation" By Karl Popper: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESPas encore d'évaluation

- Fissell Patient's NarrativeDocument9 pagesFissell Patient's NarrativeQue SabPas encore d'évaluation

- Periods of Music Grade 5 Music TheoryDocument4 pagesPeriods of Music Grade 5 Music TheoryQue SabPas encore d'évaluation

- ResearchDocument28 pagesResearchQue SabPas encore d'évaluation

- Naruto - Grief and Sorrow (Hokage's Funeral) MedleyDocument2 pagesNaruto - Grief and Sorrow (Hokage's Funeral) MedleySuluh Adi ZanuarPas encore d'évaluation

- Faulty ReasoningDocument31 pagesFaulty ReasoningChazz SatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Fallacies of Relevance: Appeal To ForceDocument6 pagesFallacies of Relevance: Appeal To ForceTomato MenudoPas encore d'évaluation

- Informal FallaciesDocument79 pagesInformal FallaciesNiel Edar BallezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Logical FallaciesDocument28 pagesLogical FallaciesTrisha Anne Aica RiveraPas encore d'évaluation

- 1H Legal Technique ReviewerDocument23 pages1H Legal Technique ReviewerRex GodMode100% (1)

- A. Q Abbasi Whatsapp Group Join Us # 0301-2383762Document45 pagesA. Q Abbasi Whatsapp Group Join Us # 0301-2383762Muhammad NumanPas encore d'évaluation

- Commfaculty - Fullerton.edu Fallacy ListDocument5 pagesCommfaculty - Fullerton.edu Fallacy ListSCRUPEUSSPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Reading As Looking For Ways of ThinkingDocument39 pagesCritical Reading As Looking For Ways of ThinkingJENNY MADALOGDOGPas encore d'évaluation

- Appeal To ForceDocument16 pagesAppeal To ForceMay Anne BarlisPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 6 Knowledge Check Study GuideDocument29 pagesWeek 6 Knowledge Check Study GuideJessica100% (1)

- (Anselm Studies and Texts, 1) Richard Campbell - Rethinking Anselm's Arguments - A Vindication of His Proof of The Existence of God (2018, Brill)Document547 pages(Anselm Studies and Texts, 1) Richard Campbell - Rethinking Anselm's Arguments - A Vindication of His Proof of The Existence of God (2018, Brill)luxfidesPas encore d'évaluation

- INFORMAL FALLACIES (Petitio Principii and Complex Question)Document3 pagesINFORMAL FALLACIES (Petitio Principii and Complex Question)Alyk Tumayan CalionPas encore d'évaluation

- A Brief Introduction To Logic and ArgumentationDocument26 pagesA Brief Introduction To Logic and ArgumentationErida PriftiPas encore d'évaluation

- Fallacies of LogicDocument5 pagesFallacies of LogicCrisanta MariePas encore d'évaluation

- Propaganda TechniquesDocument23 pagesPropaganda TechniquesIronstrikePas encore d'évaluation

- Strategies For Examining Errors in Reasoning PDFDocument4 pagesStrategies For Examining Errors in Reasoning PDFJose GainzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Logical Fallacies: 1. Non SequiturDocument9 pagesCommon Logical Fallacies: 1. Non SequiturChy_yPas encore d'évaluation

- Logic & Philosophy Sample Questions: Unit-I (Logic: Deductive and Inductive)Document6 pagesLogic & Philosophy Sample Questions: Unit-I (Logic: Deductive and Inductive)Richell OrotPas encore d'évaluation

- Logical Fallacies and The Art of DebateDocument10 pagesLogical Fallacies and The Art of DebatekarnsatyarthiPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Logical FallaciesDocument3 pages7 Logical FallaciesCarlosRamirezPas encore d'évaluation

- Logical Fallacies and Logical Ways of Thinking Explained by Srila Prabhupada THE IMPORTANCE OF LOGIC IN PREACHINGDocument20 pagesLogical Fallacies and Logical Ways of Thinking Explained by Srila Prabhupada THE IMPORTANCE OF LOGIC IN PREACHINGJayarama DasaPas encore d'évaluation

- Logic Chapter 3Document117 pagesLogic Chapter 3Sami IGPas encore d'évaluation

- Argumentative DiscourseDocument11 pagesArgumentative DiscoursecandecePas encore d'évaluation

- List of Latin Phrases (Full)Document105 pagesList of Latin Phrases (Full)馬春福Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philo Worksheet 5Document3 pagesPhilo Worksheet 5Leo LinPas encore d'évaluation