Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Long-Term Outcomes and Risk Factors Associated With Acute Encephalitis in Children

Transféré par

Novia RambakCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Long-Term Outcomes and Risk Factors Associated With Acute Encephalitis in Children

Transféré par

Novia RambakDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Long-Term Outcomes and Risk Factors Associated With

Acute Encephalitis in Children

Suchitra Rao,1,2 Benjamin Elkon,2 Kelly B. Flett,3 Angela F.D. Moss,4 Timothy J. Bernard,2,5 Britt Stroud,6 Karen M. Wilson7

1

Division of Hospital Medicine and Infectious Diseases; 2Department of Pediatrics, Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora; 3Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Department

of Medicine, Boston Children's Hospital, Massachusetts; 4Adult and Child Center for Health Outcomes and Delivery Science, University of Colorado School of Medicine, and

5

Divisions of Neurology, University of Colorado School of Medicine and Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora; 6Department of Neurology, Lee Memorial Health System, Fort

Myers, Florida, and 7Hospital Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora

Background. Factors associated with poor outcomes of children with encephalitis are not well known. We sought to determine

whether electroencephalography (EEG) findings, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) abnormalities, or the presence of seizures at

presentation were associated with poor outcomes.

Methods. A retrospective review of patients aged 0 to 21years who met criteria for a diagnosis of encephalitis admitted between

2000 and 2010 was conducted. Parents of eligible children were contacted and completed 2 questionnaires that assessed current

physical and emotional quality of life and neurological deficits at least 1year after discharge.

Results. During the study period, we identified 142 patients with an International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision diag-

nosis of meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or encephalitis. Of these patients, 114 met criteria for a diagnosis of encephalitis, and 76 of

these patients (representing 77 hospitalizations) had complete data available. Forty-nine (64%) patients were available for follow-up.

Patients admitted to the intensive care unit were more likely to have abnormal EEG results (P = .001). The presence of seizures on

admission was associated with ongoing seizure disorder at follow-up. One or more years after hospitalization, 78% of the patients

had persistent symptoms, including 35% with seizures. Four (5%) of the patients died. Abnormal MRI findings and the number of

abnormal findings on initial presentation were associated with lower quality-of-life scores.

Conclusions. Encephalitis leads to significant morbidity and death, and incomplete recovery is achieved in the majority of hos-

pitalized patients. Abnormal EEG results were found more frequently in critically ill children, patients with abnormal MRI results

had lower quality-of-life scores on follow-up, and the presence of seizures on admission was associated with ongoing seizure disorder

and lower physical quality-of-life scores.

Keywords. cerebrospinal fluid; encephalitis; meningoencephalitis; PedsQL; viral infection.

INTRODUCTION long-term sequelae include epilepsy, developmental delay,

Encephalitis is a serious illness that affects children world- learning disabilities, and chronic headaches [5].

wide. It is defined by the presence of an inflammatory process The etiological agent is an important predictor of outcomes

of the brain associated with clinical evidence of neurological in patients with encephalitis [6], the epidemiology of which is

dysfunction [1]. The initial presentation can include seizures, geographically dependent [1]. Long-term outcomes have been

headache, paresis, vision loss, hearing impairment, and behav- explored for patients with a number of different viruses, such

ioral changes [2, 3]. Diagnosis is made by clinical presentation, as herpes simplex virus (HSV) [710], Japanese encephalitis

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings, and electroencephalography [11], enterovirus [12, 13], and Epstein Barr virus [14]. However,

(EEG) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) abnormalities. in up to 75% of cases of encephalitis, an etiology is not found

For children, neurological impairment, which can lead to sig- [1, 15]. There have been few published studies regarding the

nificant morbidity and death and affect long-term quality of long-term neurological outcome of pediatric patients with

life, has been reported in 25% to 60% of cases [3, 4]. Common encephalitis, accounting for those without an etiology, using

standardized outcome measures. The use of standardized mea-

sures can enhance our understanding of the outcomes asso-

ciated with encephalitis and help us to identify potential risk

Received 20 April 2015; accepted 29 September 2015.

Correspondence: S. Rao, MBBS, Department of Pediatrics, Children's Hospital of Colorado, factors for more severe disease; these measures are used also

University of Colorado School of Medicine, B055, 13123 E 16th Ave, Aurora, CO 80045 (suchitra. for other pediatric neurological insults, such as traumatic brain

rao@childrenscolorado.org).

Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 2017;6(1):207

injury and stroke [16, 17]. Therefore, there were 2 main objec-

The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of The Journal of the tives of this study. The first objective was to use standardized

Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail:

measures to explore the long-term outcomes of children with

journals.permissions@oup.com.

DOI: 10.1093/jpids/piv075 encephalitis to further characterize the impact of this disease

20 JPIDS2017:6(March) Rao etal

state in quantifiable terms. The second objective was to deter- children with chronic medical conditions and modified on the

mine whether EEG and MRI abnormalities and the presence basis of results from this testing.

of seizures on initial presentation are risk factors for persistent

neurological abnormalities or if they impact quality of life. Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics are reported as medians (interquartile

METHODS ranges [IQRs]) for continuous data and counts (proportions)

for categorical data. The 2 and Fisher exact tests for associa-

Study Population

tion were used to compare certain clinical factors on admission

We reviewed the medical records of patients admitted to

with persistent abnormalities at least 1 year after the diagno-

Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, between 2000 and 2010

sis of encephalitis. Persistent neurological abnormalities were

with an International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision

defined as the presence of seizures, behavioral problems, or 1 or

(ICD-9) discharge diagnosis code of encephalitis, meningo-

more neurological deficits, such as weakness, speech problems,

encephalitis, or meningitis. Patients were eligible for the study

developmental delay, and learning problems. Comparisons for

if they had a diagnosis of encephalitis, which was defined as

clinical findings at admission and the presence of neurological

documented encephalopathy (depressed or altered level of con-

deficits, behavioral problems, and seizures at discharge were

sciousness lasting >24 hours, lethargy, or personality change)

also examined with the 2 and Fisher exact tests for association.

plus 2 or more of the following: temperature of >38C; new-on-

Neurological deficits at discharge were defined as the presence

set seizure(s); focal central nervous system findings; abnormal

of psychiatric problems or at least 1 physical problem, such as

EEG findings compatible with encephalitis; abnormal brain

motor deficits, ataxia/cerebellar signs, or movement disorder.

computed tomography (CT) scan or MRI results; or CSF pleo-

Spearman partial correlation was used to measure the strength

cytosis >2 standard deviations of the mean for their age [18].

of the association between PedsQL scores and clinical findings

Patients with insufficient data, antiN-methyl D-aspartate

at admission and at discharge while controlling for the effect

receptor encephalitis, or a hematologic/oncologic diagnosis

of age at the time that the survey was administered. The fol-

were excluded from the study. Demographic, clinical laboratory,

lowing empirical guidelines for interpreting the magnitude

EEG, and neuroimaging data of each patient were obtained.

of the correlation coefficients were used: values less than 0.2

Approval for the study was obtained from the Colorado Multiple

indicate weak correlation, values between 0.2 and 0.3 indicate

Institutions Review Board (08-1299). Informed written consent

moderate correlation, and values greater than 0.3 indicate large

was obtained for the follow-up questionnaires.

correlation. The McNemar test for paired data was used to test

for differences in proportions in abnormalities at admission

Follow-Up and during hospitalization against those present at discharge.

Patients who met the study criteria for a diagnosis of encephali- P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons within each

tis were eligible for follow-up if at least 1year had passed since subanalysis by using the Hochberg method, which preserved

their original diagnosis. Astructured telephone interview was the overall type Ierror rate for each subanalysis, allowing the

conducted with parents of eligible patients using 2 question- adjusted P values to be interpreted at the 0.05 level of signifi-

naires designed to assess quality of life; they were also mailed if cance. Statistics were performed by using SAS version 9.4 sta-

requested by a parent. The first questionnaire was the Pediatric tistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SPSS version 22

Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Generic Core Scales [19], (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

which is a 23-item scale designed to measure health-related

quality of life in 4 categories: physical functioning (8 items),

RESULTS

emotional functioning (5 items), social functioning (5 items),

and school functioning (5 items). The psychosocial score is We identified 142 patients with an ICD-9 diagnosis of men-

a composite of the emotional, social, and school function- ingitis, meningoencephalitis, or encephalitis during our study

ing scores. The PedsQL questionnaire was validated previ- period. Of these patients, 114 met our criteria for a diagnosis of

ously, is reliable in patient populations [20], and is suggested encephalitis and underwent chart review. Twelve patients were

as a core global outcome measure by the National Institute of excluded because of a diagnosis of antiN-methyl D-aspartate

Neurological Disorders and Stroke Common Data Elements receptor encephalitis, and 26 patients were excluded because

[16]. The second questionnaire was used to determine the per- of oncologic comorbidity or insufficient data regarding clinical

sistence of specific neurological symptoms or difficulties with presentation in the medical record. Seventy-six patients (repre-

areas of daily living such as weakness, speech, headaches, and senting 77 hospitalizations) had data available for review. One

seizures, and it covered areas relevant to encephalitis follow-up patient had a repeat hospitalization for encephalitis 3years after

that were not addressed in the PedsQL questionnaire (see the initial episode; the etiology was not identified for either pre-

Appendix). The questionnaire was pilot tested with parents of sentation. An etiology was identified in 29 (38%) of the cases,

Outcomes in Children After Encephalitis JPIDS 2017:6 (March) 21

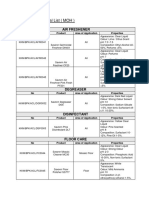

Figure1. Flow diagram showing study participants with encephalitis at Children's Hospital Colorado (20002010), from initial assessment through follow-up.

Abbreviations: HSV, herpes simplex virus; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision.

93% of which were from an infectious source. The most com- with an etiology identified had lower median physical scores

mon etiologies were HSV, enterovirus, and influenza (Figure1). than patients without an etiology identified (87.5 vs 97; P = .02),

The median age at diagnosis was 7years (IQR, 213years). One but their overall and psychosocial scores were not significantly

patient had a previous history of developmental delay, 1 had different. Patients with HSV and influenza had lower median

a history of seizures, and 2 had a history of migraine. Thirty- physical and psychosocial scores, and patients who tested posi-

two (42%) patients were admitted to the ICU, and 4 (5%) tive for enterovirus had higher median scores, but these differ-

patients died. Neurological deficits present on admission and ences were not statistically significant.

persistence of deficits at discharge are summarized in Figure2. There were no significant associations observed between fac-

Most patients who presented with motor deficits, personality tors on admission, such as CSF pleocytosis, CT/MRI or EEG

changes, and/or ataxia/cerebellar signs were likely to have reso- abnormalities, or neurological deficits present at discharge.

lution of their symptoms before discharge. Patients admitted to the ICU were more likely to have had EEG

Forty-nine patients were available for follow-up. The median abnormalities (P =.013).

time to follow-up was 1.3years. Subjects with and without fol- Long-term outcomes were assessed by evaluating the PedsQL

low-up data were similar in terms of demographics and clinical scores and the presence of neurological symptoms and signs at

characteristics (Table1). Persistent neurological outcomes and least 1year after diagnosis. Having seizures present on admis-

PedsQL scores with normative data [20] are listed in Tables 2 sion was significantly associated with ongoing seizures at

and 3, respectively. Persistent deficits were reported in 38 (78%) least 1 year after the diagnosis of encephalitis (94% vs 42%; P

patients. The most common residual neurological symptoms = .0036). Partial correlation coefficients of clinical factors on

reported were psychiatric abnormalities, weakness, behav- admission with PedsQL scores at least 1year after diagnosis are

ioral or cognitive deficits, vision problems, and headaches. presented in Table4. After removing the effects of age, having

Seventeen patients (35%) reported ongoing seizures. Patients abnormal MRI results on admission was associated with lower

22 JPIDS2017:6(March) Rao etal

Figure2. Neurological deficits and persistence of symptoms and signs on discharge among patients with encephalitis at Children's Hospital Colorado,

20002010 (N = 49); significant differences in proportions were evaluated by the 2 and Fisher exact tests.

psychosocial and physical scores, and the presence of seizures on The results of our study suggest a role for MRI for not only

admission correlated with lower physical scores. The presence of diagnosing and assisting with the etiology of encephalitis but

EEG abnormalities on admission did not correlate with PedsQL also the prognostic information it may provide. Although

scores. However, an increase in the number of clinical factors abnormal MRI findings in our study were not associated with

on admission (MRI abnormalities, EEG abnormalities, seizures, findings at discharge or gross neurological deficits, they were

and CSF pleocytosis) correlated with lower PedsQL scores. potentially associated with more subtle deficits identified by the

PedsQL questionnaire. The strongest correlation was noted for

the psychosocial score, which evaluates mental and emotional

DISCUSSION

health and incorporates perception of self and ability to func-

In our study of long-term outcomes of children with encephali- tion in the community. Klein etal [2] reported that MRI abnor-

tis, we found that almost 80% of patients with encephalitis had malities were predictive of abnormal neurological outcome at

persistent neurological symptoms on long-term follow-up. MRI hospital discharge, but their study did not follow patients to

findings and the presence/absence of seizures on admission assess long-term outcomes. Wang etal [3] reported that focal

were helpful in predicting long-term outcomes. We found that cortical parenchymal abnormalities that appeared on MRI pre-

abnormal MRI findings and seizures were correlated with lower dicted poorer long-term outcomes. Despite having detailed

quality-of-life scores. The presence of seizures at presentation radiographic characterization of the lesions in those patients

was associated with patients having ongoing seizure disorder. with MRI abnormalities, our study did not find an association

Finally, although EEG abnormalities were more commonly seen between specific MRI abnormalities and adverse outcome, but

among critically ill patients, EEG findings were not helpful in this finding might have been limited by samplesize.

predicting long-term outcomes. Given the limited data regard- In contrast, although EEG is a useful tool for assessing

ing long-term outcomes in children with encephalitis, these acute brain dysfunction [4], EEG findings do not predict

findings are important for informing which factors on presen- long-term outcomes. The results of our study show that

tation might predict quality-of-life outcomes. any EEG abnormalities, particularly severe EEG findings,

Outcomes in Children After Encephalitis JPIDS 2017:6 (March) 23

Table1. Demographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Hospital Course of Patients With Encephalitis Seen at Children's Hospital Colorado, 20002010a

Variable Total Patients Follow-Up Group (N = 49) No-Follow-Up Group (N = 27)b

Demographics

Age at diagnosis, years; median (interquartile range) 7 (2.612.7) 6.8 (2.612.8) 7.9 (2.411.6)

Male 41 (54.0) 25 (51.0) 16 (59.3)

Ethnicity/race

White 47 (61.8) 31 (63.3) 16 (59.3)

White (Hispanic) 19 (24.7) 13 (26.5) 5 (18.5)

Black 1 (1.3) 1 (2) 0 (0)

Asian 3 (4) 2 (4) 1 (4)

Other 3 (4) 0 (0) 3 (11)

Unknown 3 (4) 2 (4) 1 (4)

Total Episodes of Encephalitis Follow-Up Group (N = 49) No-Follow-Up Group (N = 28)b

Clinical presentation/comorbidity

Any underlying comorbidity 11 (14.5) 8 (16.7) 3 (10.7)

History of recent acute illness 37 (49.3) 21 (44.7) 16 (57.1)

Headache 30 (39.3) 22 (44.9) 8 (28.6)

Behavioral changes 29 (38.2) 20 (41.7) 9 (32.1)

Altered mental status 77 (100) 49 (100) 28 (100)

Fever 49 (64) 31 (63.3) 18 (64.3)

Seizures 47 (62) 29 (60.4) 18 (64.3)

Central nervous system abnormality 33 (43) 23 (46.9) 10 (35.7)

At least 1 physical finding 45 (59.2) 29 (60.4) 16 (57.1)

Motor deficit 37 (48.7) 23 (47.9) 14 (50.0)

Ataxia/cerebellar signs 21 (27.6) 14 (29.2) 7 (25.0)

Movement disorder 8 (10.7) 6 (12.8) 2 (7.1)

Psychiatric problem 22 (28.9) 16 (33.3) 6 (21.4)

Laboratory/imaging/EEG findings

CSF pleocytosis 61 (80) 40 (83.3) 21 (75.0)

MRI/CT abnormalities 39 (51.3) 26 (54.2) 13 (46.4)

EEG abnormalities 47 (71.2) 31 (73.8) 16 (66.7)

Treatment

IVIg 5 (6.8) 4 (8.9) 1 (3.6)

Steroids 19 (27.5) 11 (25.0) 8 (32.0)

<21days of acyclovir 37 ( 59.7) 19 (51.4) 18 (72.0)

>21days of acyclovir 25 (40.3) 18 (48.6) 7 (28.0)

Hospital course

Rehabilitation admission 20 (29.0) 15 (34.1) 5 (20.0)

ICU admission 32 (44) 18 (38.3) 14 (56.0)

Days in ICU 4 (27) 4.5 (26) 3.0 (27)

Length of stay, days; median (interquartile range) 7.0 (3.921.0) 7.2 (3.021.0) 7.0 (3.922.6)

Death 4 (5.8) 0 (0) 4 (16)

Clinical factors on discharge

At least 1 physical finding 18 (23.7) 11 (22.9) 7 (25.0)

Motor deficit 16 (21.1) 10 (20.8) 6 (21.4)

Ataxia/cerebellar signs 4 (5.3) 2 (4.2) 2 (7.1)

Movement disorder 3 (4) 1 (2.1) 2 (7.1)

Psychiatric problem 8 (10.5) 5 (10.4) 3 (10.7)

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; EEG, electroencephalography; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

a

Values shown are number (percentage) unless otherwise specified.

b

There was no statistically significant difference between the follow-up and no-follow-up groups.

were more prevalent in patients admitted to the pediatric clinical signs and symptoms at presentation are more likely to

ICU. We did not, however, find an independent association have EEG abnormalities, but they do not necessarily correlate

between EEG abnormalities or ICU stay and poor long-term with long-term outcomes.

outcomes, in contrast to the findings of Wang etal [3]. Our Although EEG findings may not be useful for prognosis,

findings suggest that patients who present with more severe our study results show that seizures on initial presentation

24 JPIDS2017:6(March) Rao etal

Table2. Persistent Neurological Deficits at Least 1 Year After Diagnosis Table3. PedsQL Scores for Patients at Least 1 Year After Diagnosis

of Encephalitis Among Patients Seen at Children's Hospital Colorado, of Encephalitis Among Patients Seen at Children's Hospital Colorado,

20002010 (N = 49) 20002010 (N = 49)

Variable n % (95% CI) Age Category PedsQL Score (Median [IQR])

Neurological deficit Physicala 94 (75100)

Any deficit 38 78 (6690) 24 y of age 95 (53100)

Weakness 16 33 (2046) 57 y of age 97 (30100)

Behavioral problem 15 31 (1844) 812 y of age 89 (6397)

Developmental delay 17 35 (2248) >13 y of age 94 (88100)

Anxiety/depression 18 37 (2351) Psychosociala 75 (6092)

Vision problem 17 35 (2248) 24 y of age 73 (56100)

Speech problem 15 31 (1844) 57 y of age 76 (5691)

Sleep problem 9 18 (729) 812 y of age 78 (6293)

Learning problem 20 41 (2755) >13 y of age 75 (6079)

Swallowing problem 5 10 (218)

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; PedsQL, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; SD, standard deviation.

Hearing problem 3 6 (013) a

Parent proxy-report mean scores for PedsQL physical health among 8696 families of healthy children were

Headache 17 35 (2248) 84.08 (SD, 19.7), and mean scores for psychosocial health among 8714 families were 81.24 (SD, 15.34) in a

study by Varni etal [20].

Seizures 17 35 (2248)

Services/aids/medications required

On antiepileptic(s) 12 24 (1236)

did not identify specific outcome domains as we did. It should

Glasses 13 27 (1539)

Hearing aid 1 2 (06) be noted that the most common etiological agents reported by

Speech therapy 24 49 (3563) Misra etal, specifically, Japanese encephalitis and dengue, were

Physical therapy 24 49 (3563) different than those in our study. In addition, our finding that

Occupational therapy 24 49 (3563) the presence of seizures at presentation increased the risk of

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval. subsequent seizure disorder was described previously [4]. These

findings raise questions about whether identifying and optimiz-

correlated with poorer long-term outcomes, which has been ing seizure management early in the hospital course could serve

corroborated by other reports [2, 3]. From their study, Misra as a neuroprotective strategy, and they warrant furtherstudy.

etal [21] reported that seizures resulting from encephalitis were The majority of previous studies in which long-term out-

associated with poor outcomes at 3months follow-up. The study comes of patients with encephalitis were explored focused on

Table4. Partial Correlations of PedsQL Scores (Obtained at Least 1 Year After Diagnosis) With Clinical Factors on Admission After Adjusting for Age

Among Patients With Encephalitis Seen at Children's Hospital Colorado, 20002010

Physical Score Psychosocial Score Overall Score

Clinical Factor on Admission n Median Spearman rhoa Median Spearman rhoa Median Spearman rhoa

MRI/CT 26 71.9 0.26 88.8 0.43 b

76.5

Abnormal 22 77.4 100 81.4 0.29

Normal

EEG 31 73.3 0.05 90.6 0.14 76.2

Abnormal 11 75.0 100 80.0 0.06

Normal

Seizures 29 75.0 0.08 90.6 0.2 76.3

Yes 19 87.5 96.9 85.0 0.11

No

CSF pleocytosis 40 75.0 0.16 93.8 0.05 78.0

Yes 8 85.8 94.4 84.6 0.09

No

No. of clinical factors present 10 92.5 0.24 100 0.34 92.1

1 14 76.9 93.8 74.2 0.22

2 12 65.3 98.4 68.3

3 13 76.3 87.5 72.9

4

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; EEG, electroencephalography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PedsQL, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory.

a

Values of 0.10.2 represent weak correlation; values of 0.20.3 represent moderate correlation; and values of >0.3 represent strong correlation.

b

The adjusted P value is <.05.

Outcomes in Children After Encephalitis JPIDS 2017:6 (March) 25

a specific etiological agent [7, 11, 13, 14, 22]. However, given presentation correlate with worse quality-of-life outcomes. The

that the majority of cases of encephalitis are without an etiology, presence of seizures on presentation predicts subsequent sei-

we sought to explore the long-term outcomes of encephalitis zure disorder and is associated also with lower physical qual-

regardless of whether an agent was identified, because it is more ity-of-life scores. Our data suggest that MRI findings might

relevant to the usual clinical setting. We found that the identi- provide some prognostic information. Close follow-up of these

fication of an etiological agent did not influence quality-of-life patients is advised, because they are at risk of impairment

scores, but our data are limited by the lack of standardized test- with regards to their quality of life and subsequent epilepsy.

ing at our institution. Additional prospective studies with larger cohorts and more

Although other studies have explored short-term outcomes detailed outcome measures are needed to further determine

during hospitalizations [2] or focused primarily on long-term risk factors that are predictive of poor outcomes.

outcomes [23, 24], a strength of our study is that we report both

Note

long-term and short-term outcomes. In addition to reporting

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

initial presentation and outcomes at discharge, we sought to fol- All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential

low patients at least 1year after their initial diagnosis of enceph- Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the con-

alitis, by which time their deficits are usually persistent [25]. We tent of the manuscript have been disclosed.

selected the PedsQL questionnaire for our study because it was

References

validated for use in studies of neurological disorders, it is brief

1. Tunkel AR, Glaser CA, Bloch KC etal. The management of encephalitis: clinical

and reliable, and it can be administered by telephone, which practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis

likely contributed to our high response rate. Because this tool 2008; 47:30327.

2. Klein SK, Hom DL, Anderson MR, Latrizza AT, Toltzis P. Predictive factors of

does not account for specific deficits, we included an additional short-term neurologic outcome in children with encephalitis. Pediatr Neurol

questionnaire related to neurological deficits, which provided 1994; 11:30812.

3. Wang IJ, Lee PI, Huang LM etal. The correlation between neurological evalua-

further insight into the long-term morbidity associated with tions and neurological outcome in acute encephalitis: a hospital-based study. Eur

encephalitis. J Paediatr Neurol 2007; 11:639.

4. Fowler A, Stodberg T, Eriksson M, Wickstrom R. Childhood encephalitis in

There are limitations to our study. Our study showed an Sweden: etiology, clinical presentation and outcome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2008;

increase in the number of deficits correlated with lower phys- 12:48490.

5. Clarke M, Newton RW, Klapper PE et al. Childhood encephalopathy: viruses,

ical, psychosocial, and overall PedsQL scores. However, we

immune response, and outcome. Dev Med Child Neurol 2006; 48:294300.

were not able to determine whether they were independent 6. Rautonen J, Koskiniemi M, Vaheri A. Prognostic factors in childhood acute

predictors because of our small sample size. There was a sig- encephalitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1991; 10:4416.

7. Elbers JM, Bitnun A, Richardson SE etal. A 12-year prospective study of child-

nificant percentage of patients excluded from analysis because hood herpes simplex encephalitis: is there a broader spectrum of disease?

of incomplete medical records, which may have skewed our Pediatrics 2007; 119:e399407.

8. Corey L, Whitley RJ, Stone EF, Mohan K. Difference between herpes simplex virus

data. Selection bias exists because of the nature of our fol- type 1 and type 2 neonatal encephalitis in neurological outcome. Lancet 1988;

low-up. Also, there were variable times to patient follow-up for 1:14.

9. Whitley R, Arvin A, Prober C et al. Predictors of morbidity and mortality in

the completion of the questionnaires. However, because most neonates with herpes simplex virus infections. The National Institute of Allergy

patients with encephalitis who show full recovery are likely to and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. N Eng J Med 1991;

324:4504.

do so within 12months of their initial diagnosis [4], we ensured

10. Kimberlin DW, Lin CY, Jacobs RF etal. Natural history of neonatal herpes simplex

that follow-up was obtained at least 1year after their diagnosis, virus infections in the acyclovir era. Pediatrics 2001; 108:2239.

by which time their clinical characteristics were more likely to 11. Ooi MH, Lewthwaite P, Lai BF etal. The epidemiology, clinical features, and long-

term prognosis of Japanese encephalitis in central Sarawak, Malaysia, 19972005.

be persistent. In addition, there are certain neurological defi- Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47:45868.

cits that are nonspecific and may not be related to encephalitis 12. Huang MC, Wang SM, Hsu YW etal. Long-term cognitive and motor deficits after

enterovirus 71 brainstem encephalitis in children. Pediatrics 2006; 118:e17858.

(such as the presence of headaches) or may have been present 13. Chang LY, Hsia SH, Wu CT et al. Outcome of enterovirus 71 infections with

before the diagnosis of encephalitis. We documented in our or without stage-based management: 1998 to 2002. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;

23:32732.

detailed questionnaire only those symptoms that were new after 14. Doja A, Bitnun A, Jones EL etal. Pediatric Epstein-Barr virus-associated enceph-

the diagnosis of encephalitis, but reporting was subject to recall alitis: 10-year review. J Child Neurol 2006; 21:38591.

15. Koskiniemi M, Korppi M, Mustonen K etal. Epidemiology of encephalitis in chil-

bias and may have influenced the PedsQL scores. A prospec-

dren. Aprospective multicentre study. Eur J Pediatr 1997; 156:5415.

tive longitudinal study that includes active methods of subject 16. McCauley SR, Wilde EA, Anderson VA et al. Recommendations for the use of

follow-up and formal neuropsychological assessments linking common outcome measures in pediatric traumatic brain injury research. J

Neurotrauma 2012; 29:678705.

early indicators to etiology, disease progression, and prognosis 17. Di Battista A, Godfrey C, Soo C, Catroppa C, Anderson V. Does what we measure

would yield an improved understanding of long-term outcomes. matter? Quality-of-life defined by adolescents with brain injury. Brain Inj 2015;

29:110.

This study of long-term outcomes of patients hospitalized 18. Kolski H, Ford-Jones EL, Richardson S etal. Etiology of acute childhood enceph-

with encephalitis found that long-term deficits are seen in alitis at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 19941995. Clin Infect Dis 1998;

26:398409.

approximately 80% of patients, and subsequent seizure dis- 19. The PedsQL Measurement Model for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory.

order is seen in 35% of patients. Abnormal MRI findings at Available at: http://www.pedsql.org/. Accessed April 15, 2015.

26 JPIDS2017:6(March) Rao etal

20. Varni JW, Limbers CA, Neighbors K et al. The PedsQL infant scales: feasibility, Swallowing problems no yes

internal consistency reliability, and validity in healthy and ill infants. Qual Life Res

2011; 20:4555. Hearing problems or deafness no yes

21. Misra UK, Kalita J. Seizures in encephalitis: predictors and outcome. Seizure 2009; Headaches no yes

18:5837.

22. Engman ML, Adolfsson I, Lewensohn-Fuchs I etal. Neuropsychologic outcomes

in children with neonatal herpes encephalitis. Pediatr Neurol 2008; 38:398405. If you have answered yes to any of the above, was this present

23. Schmidt A, Buhler R, Muhlemann K, Hess CW, Tauber MG. Long-term outcome

before the diagnosis of encephalitis? If so, please circle:Since

of acute encephalitis of unknown aetiology in adults. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;

17:6216. your child's encephalitis, does he or she currently:

24. Mailles A, De Broucker T, Costanzo P etal. Long-term outcome of patients pre-

senting with acute infectious encephalitis of various causes in France. Clin Infect

Dis 2012; 54:145564. Use a wheelchair? no yes

25. Fowler A, Stodberg T, Eriksson M, Wickstrom R. Long-term outcomes of acute Wear glasses? no yes

encephalitis in childhood. Pediatrics 2010; 126:e82835.

Wear hearing aids? no yes

APPENDIX Has your child ever needed any of the following services after

TCH Neurological Outcomes Questionnaire discharge from a hospital for encephalitis?

Child's Name:

Date of Birth: Speech therapy no yes

Your Name: Occupational therapy no yes

Relationship to child: Physical therapy no yes

General health: Seizures:

In general, would you say your child's health is: 2. Does your child have seizures since having encephalitis?

ExcellentVery goodGoodFairPoor noyes

If the answer is yes, answer questions 35 below:

Have you been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health profes- 3. What best describes the type of seizure pattern your child has:

sional that your child has any of the following problems?

Staring episodes

Weakness of the arms or legs no yes Focal seizures (affecting one part of the body)

Behavior problems no yes Generalized seizures (affecting multiple parts of the body)

Developmental delay no yes Other (describe)

Depression or anxiety problems no yes

Vision problems no yes 4. During the past 4 weeks, how many seizures has your child

Speech problems no yes had?

Sleep disturbance no yes 5. Does your child take medication(s) for the seizures?

Learning problems no yes noyes

Outcomes in Children After Encephalitis JPIDS 2017:6 (March) 27

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- 07 Treatment of Acute PDFDocument6 pages07 Treatment of Acute PDFNovia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- Adhd Identifying 2008Document1 pageAdhd Identifying 2008Novia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- The Physiotherapy of BronchiectasisDocument5 pagesThe Physiotherapy of BronchiectasisNovia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- Crameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesDocument8 pagesCrameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesNovia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- (2008 13 Halaman) Rehabilitation in Patients With Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument9 pages(2008 13 Halaman) Rehabilitation in Patients With Rheumatoid ArthritisNovia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- Crameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesDocument8 pagesCrameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesNovia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- Original Report: J Rehabil Med 45Document12 pagesOriginal Report: J Rehabil Med 45Novia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- 2803 6121 1 SM PDFDocument6 pages2803 6121 1 SM PDFNovia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- Current Practice of Occupational Therapy For Children With AutismDocument8 pagesCurrent Practice of Occupational Therapy For Children With AutismNovia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- (1960) Califmed00101-0080Document4 pages(1960) Califmed00101-0080Novia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- (2003) 208-419-1-SMDocument4 pages(2003) 208-419-1-SMNovia RambakPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Contents Serbo-Croatian GrammarDocument2 pagesContents Serbo-Croatian GrammarLeo VasilaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Berenstain Bears and Baby Makes FiveDocument33 pagesThe Berenstain Bears and Baby Makes Fivezhuqiming87% (54)

- Brochure - Digital Banking - New DelhiDocument4 pagesBrochure - Digital Banking - New Delhiankitgarg13Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chinese AstronomyDocument13 pagesChinese Astronomyss13Pas encore d'évaluation

- Joshua 24 15Document1 pageJoshua 24 15api-313783690Pas encore d'évaluation

- Diode ExercisesDocument5 pagesDiode ExercisesbruhPas encore d'évaluation

- Tamil and BrahminsDocument95 pagesTamil and BrahminsRavi Vararo100% (1)

- STAFFINGDocument6 pagesSTAFFINGSaloni AgrawalPas encore d'évaluation

- La Navassa Property, Sovereignty, and The Law of TerritoriesDocument52 pagesLa Navassa Property, Sovereignty, and The Law of TerritoriesEve AthanasekouPas encore d'évaluation

- Approved Chemical ListDocument2 pagesApproved Chemical ListSyed Mansur Alyahya100% (1)

- Sodium Borate: What Is Boron?Document2 pagesSodium Borate: What Is Boron?Gary WhitePas encore d'évaluation

- List de VerbosDocument2 pagesList de VerbosmarcoPas encore d'évaluation

- CEI and C4C Integration in 1602: Software Design DescriptionDocument44 pagesCEI and C4C Integration in 1602: Software Design Descriptionpkumar2288Pas encore d'évaluation

- Catastrophe Claims Guide 2007Document163 pagesCatastrophe Claims Guide 2007cottchen6605100% (1)

- Algebra. Equations. Solving Quadratic Equations B PDFDocument1 pageAlgebra. Equations. Solving Quadratic Equations B PDFRoberto CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- 2023-Tutorial 02Document6 pages2023-Tutorial 02chyhyhyPas encore d'évaluation

- OglalaDocument6 pagesOglalaNandu RaviPas encore d'évaluation

- SATURDAY - FIRST - PDF (1)Document3 pagesSATURDAY - FIRST - PDF (1)Manuel Perez GastelumPas encore d'évaluation

- Oxford Reading Circle tg-4 2nd EditionDocument92 pagesOxford Reading Circle tg-4 2nd EditionAreeb Siddiqui89% (9)

- Islamic Meditation (Full) PDFDocument10 pagesIslamic Meditation (Full) PDFIslamicfaith Introspection0% (1)

- Chapter 4 INTRODUCTION TO PRESTRESSED CONCRETEDocument15 pagesChapter 4 INTRODUCTION TO PRESTRESSED CONCRETEyosef gemessaPas encore d'évaluation

- Analog Electronic CircuitsDocument2 pagesAnalog Electronic CircuitsFaisal Shahzad KhattakPas encore d'évaluation

- Calendar of Cases (May 3, 2018)Document4 pagesCalendar of Cases (May 3, 2018)Roy BacaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Butterfly Valve Info PDFDocument14 pagesButterfly Valve Info PDFCS100% (1)

- Sample Midterm ExamDocument6 pagesSample Midterm ExamRenel AluciljaPas encore d'évaluation

- In The World of Nursing Education, The Nurs FPX 4900 Assessment Stands As A PivotalDocument3 pagesIn The World of Nursing Education, The Nurs FPX 4900 Assessment Stands As A Pivotalarthurella789Pas encore d'évaluation

- Percy Bysshe ShelleyDocument20 pagesPercy Bysshe Shelleynishat_haider_2100% (1)

- The Training Toolbox: Forced Reps - The Real Strength SenseiDocument7 pagesThe Training Toolbox: Forced Reps - The Real Strength SenseiSean DrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature, and The Human Spirit: A Collection of QuotationsDocument2 pagesNature, and The Human Spirit: A Collection of QuotationsAxl AlfonsoPas encore d'évaluation

- Focus Charting of FDocument12 pagesFocus Charting of FRobert Rivas0% (2)