Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

When Do Patents Encourage Disclosure?

Transféré par

Joshua GansTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

When Do Patents Encourage Disclosure?

Transféré par

Joshua GansDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

When do patents encourage disclosure?

Joshua Gans

Tirole Mini-Course, 2010

Sunday, 11 July 2010

The importance of disclosure

xt Increased

New Goods Productivity

at t

t

A Appropriated

Increase in

Knowledge

δ H A (At + A t ) t +1

A

Future Knowledge

R&D Productivity

Spillover

Sunday, 11 July 2010

The importance of disclosure

• Endogenous growth theory

• Disclosures drive the rate of growth in income per capita

• Mechanisms for disclosure

• Patent requirements

“The owner of a design has property rights over its use in the production of

a new producer durable but not over its use in research. If an inventor has a

patented design for widgets, no one can make or sell widgets without the

agreement of the inventor. On the other hand, other inventors are free to

spend time studying the patent application for the widget and learn

knowledge that helps in the design of a wodget. The inventor of the widget

has no ability to stop the inventor of a wodget from learning from the

design of a widget. (Romer, 1990, S84-85, emphasis added)”

• Publications

• But disclosures assist competition: choice to disclose is endogenous

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Some history

• Famous examples of secrecy

• Forceps delivery: invented by Chamberlen family in France (mid 1500s).

Emigrated to England and kept method secret for a century.

• Nineteenth Century debate over patents (Machlup-Penrose, 1950) was the

origin of the ‘contract theory of patents’

• “The patent constitutes a genuine contract between society and inventor;

if society grants him a temporary guaranty, he discloses the secret which

he could have guarded: quid pro quo, this is the very principle of

equity.” (Louis Wolowski, 1869)

• The idea is that disclosures would mitigate against wasteful duplication

although the innovator would have to be induced to ‘sign’ the social

contract.

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Disclosures and entry

d : level of disclosure

∂F Easier to reverse

Pr(Entry) = F(d) >0

∂d engineer

Innovator Π

− F(d)(Π − π )

Maximises Monopoly

Profit

Competitive

Profit

d =0

*

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Patents and disclosures

∂F

Pr(Entry) = F(dPAT , s) <0

∂s

minimum disclosure strength of patent

requirements protection Makes successful

entry difficult

Π − F(dPAT , s)(Π − π ) > Π − F(0, 0)(Π − π )

Profits from Patenting Profits from Secrecy

F(0, 0) > F(dPAT , s)

Patent if reduce likelihood of entry

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Welfare

• Patents are a ‘free option’ for monopolisation

• “No one can call that a fair bargain that which is voluntary on one side, and

involuntary on the other.” (Rogers, 1863)

• High disclosure requirement

• Reduces costs of duplication, k(d)

• Reduces patenting

Patenting reduces social duplication costs if ...

F(0, 0) k(dPAT )

>

F(dPAT , s) k(0)

<1

Denicolo & Franzoni, 2004 (vs Bessen, 2005)

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Licensing and disclosure: patents

• Suppose that the innovator is not the ‘best’ agent to commercialise the

innovation

• Example: established firm with complementary assets that must otherwise

be duplicated at cost higher than the monopoly profits.

• Suppose that disclosure requires effort and is also non-contractible (tacit

knowledge; Arora, 1995) but increases profits, Π’(d) > 0. Will only choose to

disclose prior to agreement (no profit sharing)

• Innovator appropriates some share of the gains from trade

Gains from trade: Π(d) − F(d, s)Π(d)

∂d

≥0 − ∂F

Π′(d) − ∂2 F

Π(d) > 0

*

∂s ∂s

∂d∂s

<0

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Licensing under secrecy

• Arrow’s disclosure problem

• If want someone to buy an idea, need to disclose the idea to assess quality. Makes you

vulnerable to expropriation.

• Example: Bob Kearns and the intermittent windshield wiper

• Scorched earth threat

• Suppose that there are two (or more) potential buyers of an idea and they compete with one

another

• Threaten to give idea to rival firm if buyer does not pay (Anton & Yao, 2004)

• Tacit knowledge

• Suppose effort is required to transfer tacit knowledge

• Then, once paid for, no effort is undertaken but without a patent, vulnerable to expropriation.

• Right to exclude, creates incentive to transfer tacit knowledge (Arora, 1995)

Patents overcome the disclosure problem without resort to threats

and encourage licensing

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Increased patent rights led to greater licensing

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Gans, Hsu & Stern 2002

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Timing of Licensing

from Gans, Hsu & Stern, 2008

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Markets for ideas

• Rarely see fully-fledged markets for ideas

• Usually bilateral negotiations with little use of competitive options

• Multi-lateral exchange of ideas is observed

• Examples: academic science, open source communities, social networks

• Many challenges in designing markets

• Thickness

• Timing

• Risk

• Repugnance

Possible that markets for ideas work best when the price

is equal to zero!

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Patents and Scientific Disclosure

• Scientists have non-monetary motivations

• Merton, Sociology of Science

• Stern (2004): Scientists pay to be scientists

• Patents and commercial motivations create conflicts

• Aghion, Dewatripont & Stein (2008): academic freedom as a contracting

issue

• Heller and Eisenberg: patents are hindering open science

• Empirical association of patents and publications

• Murray (various): patents are often paired with papers and vice versa

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Choice of disclosure regimes

Publication disclosure (d)

0 D

Commercial Patent-Paper

1

Science Pairs

Patent

(i)

0 Secrecy Open Science

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Preferences

• Scientist

U= w + bS d

wage kudos

• Firm (Funder)

Π − k − w − F(d, dPAT , s)(Π − π )

Capital

Cost

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Probability of Entry

1 Pr (Disclosure)

1

= (1 − α ) ( i Pr (Learn from Patent)+Pr(Learn from Pub))

π + α i Pr(Learn from Either)

= (1 − α ) ( idPAT + d ) + α ( idPAT + d − idPAT d )

(1 − i ρ )π = idPAT + d − α idPAT d

Random

(1 − i ρ )π − iλ + bE (id PAT + d − α id PAT d)

Pr(Disclosure) Fixed

= Pr (entry) Cost, θ

(1 − i ρ )π − iλ

0 0

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Expected Profits

Π

− k − w − Pr(successful entry)(Π − π )

Monopoly capital Competitive

Profit cost Profit

Pr (successful entry)

= (1 − i ρ )Pr(entry)

= (1 − i ρ ) ( (1 − i ρ )π − iλ + bE (idPAT + d − α idPAT d))

The potential for entry is increasing in both patenting and publication

disclosure, while the cost of entry may or may not rise if there is a patent.

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Total surplus maximisation

max d bS d + Π − k − F(d, dPAT , s)(Π − π )

• Patents and publication are complementary

• Driver 1: congruence (overlap) between knowledge in patent and knowledge

in publication

• Driver 2: patent protection reduces competitive risk from published

disclosures

∂ TS

2

∂F 2

=− (Π − π ) > 0

∂d∂s ∂d∂s

<0

• Driver 3: when w = 0, patent protection increases commercial returns and

greater disclosure rights are the only means by which these can be shared

with the scientist

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Complementarity

Patent

strength

Commercial Patent-Paper Pairs

Science

Open

Secrecy

Science

Kudos

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Generating Substitutability

Static model yields several clear drivers of

complementarity between patents and publications

Theory of patent-paper pairs

Micro-foundation for endogenous growth assumption

Conflicting empirical evidence

Murray and Stern: citations fall following patent grant

Williams: fewer follow-on commercialised products when

scientific knowledge subject to IP protection

Empirical research identifies impact on follow-on research

direction and acknowledgment (source of kudos)

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Licensing cumulative innovation

• Suppose that future research teams build on current innovation

• Disclosures reduce costs to future research teams

• Having a patent, gives current research team an opportunity to extract some

future innovative rents through licensing

• Suppose that licensing is accompanied by full disclosure (no non-

contractibility problem)

• Publication may allow some knowledge transfer even without licensing

• Therefore, publication reduces the future license fee

• As future licensing is only possible with a patent, it follows that stronger

patent incentives may cause a reduction in publication incentives

• This is countered by static publication incentives and also scientist’s desire

for future kudos (through citation)

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Substitutability

Patent

strength Commercial

Science

Patent-Paper Pairs

Open

Secrecy Science

Kudos

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Strategic publication

• Multi-stage R&D race

• Suppose one firm is leading (closer to obtaining a patent)

• The other firm has an incentive to publish intermediate results to change

the prior art and shift forward the patent ‘prize’ (Bar, 2006)

• Observed in DNA sequencing races (Eisenberg, 2000)

• Firm with existing, core patent

• Faces competition from follow-on innovators

• Firm with patent has incentive to publish to shift forward the next

generation patent threshold

• Not clear how important ‘defensive publication’ is empirically

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Some References

Aghion, P., Dewatripont, M., & Stein, J. 2009. Academic freedom, private-sector focus and the process of innovation. RAND Journal of

Economics, 39(3), pp.617-635.

Anton, J.J. and D.A. Yao (1994), “Expropriation and Inventions: Appropriable Rents in the Absence of Property Rights,” American

Economic Review, 84 (1), pp. 190-209.

Arora, A. (1995), “Licensing Tacit Knowledge: Intellectual Property Rights and the Market for Know-How,” Economics of Innovation & New

Technology, 4, pp. 41-59.

Arrow, K. 1962. Economic Welfare and the Allocation of Resources for Invention. R. Nelson, ed. The Rate and Direction of Inventive

Activity. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 609-25.

Bar, T. 2006. Defensive Publications in an R&D Race. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 15 (1), 229-254.

Bessen, J. (2005), “Patents and the Diffusion of Technical Information,” Economics Letters.

Denicolo`, Vincenzo, Franzoni, Luigi Alberto, 2004. The contract theory of patents. International Review of Law and Economics 34, 365–

380.

Gans, J.S., D.H. Hsu and S. Stern (2002), “When Does Start-up Innovation Spur the Gale of Creative Destruction?” RAND Journal of

Economics, 33, pp.571-86.

Gans, J.S., D.H. Hsu and S. Stern (2008), “The Impact of Uncertain Intellectual Property Rights on the Market for Ideas: Evidence for

Patent Grant Delays,” Management Science, 54(5), pp.982-997.

Gans, J.S. and S. Stern (2010), “Is there a market for ideas?” Industrial and Corporate Change.

Machlup, Fritz, and Penrose, Edith, 1950. The patent controversy in the nineteenth century. The Journal of Economic History 10 (1), 1–29.

Merton, R.K. 1973. The normative structure of science. In The sociology of science: Theoretical and empirical investigations: 267-280 (Ch.

13). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Murray, F. 2002. Innovation as co-evolution of scientific and technological networks: Exploring tissue engineering. Research Policy, 31

(8-9): 1389-1403.

Murray, F., & Stern, S. 2007. Do formal intellectual property rights hinder the free flow of scientific knowledge? An empirical test of the anti-

commons hypothesis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 63(4), 648-687.

Stern, Scott. 2004. Do scientists pay to be scientists? Management Science. 50(6), pp.835-853.

Williams, H. 2009. Intellectual Property Rights and Innovation: Evidence from the Human Genome. mimeo., Harvard

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Submission Open Science 11-07-28Document7 pagesSubmission Open Science 11-07-28Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- Getting Cross With The Media and Cross-Media Ownership: Wednesday, March 01, 2006 Joshua GansDocument3 pagesGetting Cross With The Media and Cross-Media Ownership: Wednesday, March 01, 2006 Joshua GansCore ResearchPas encore d'évaluation

- Network & Digital Market Strategy - Online ParticipationDocument155 pagesNetwork & Digital Market Strategy - Online ParticipationJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- Are Prices Higher Under An Agency Model Than A Wholesale Pricing Model?Document1 pageAre Prices Higher Under An Agency Model Than A Wholesale Pricing Model?Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- The Delicate Desire For MonopolyDocument35 pagesThe Delicate Desire For MonopolyJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of The Internet On Advertising Markets For News MediaDocument27 pagesThe Impact of The Internet On Advertising Markets For News MediaJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2006 Sept Encourage That Spark-BRW-06!09!14Document3 pages2006 Sept Encourage That Spark-BRW-06!09!14Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2006 Mar Fee Change Too Much Credit Age-Credit-06!03!17Document2 pages2006 Mar Fee Change Too Much Credit Age-Credit-06!03!17Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2006 June Baby Bonus Birthing PainDocument2 pages2006 June Baby Bonus Birthing PainJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2006 May GailbraithDocument2 pages2006 May GailbraithJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- T3 Must Ring in Rule ChangesDocument2 pagesT3 Must Ring in Rule ChangesCore ResearchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2004 Sept CostPlus-04-08-24Document2 pages2004 Sept CostPlus-04-08-24Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- New Matilda TelstraDocument3 pagesNew Matilda TelstraJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- Age Telco 05 10 03Document1 pageAge Telco 05 10 03Core ResearchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2005 Oct Dirty Harry Age-Nobel-05!10!24Document2 pages2005 Oct Dirty Harry Age-Nobel-05!10!24Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2006 Aug No Longer Self Evident NM-NetNeutrality-06!08!25Document4 pages2006 Aug No Longer Self Evident NM-NetNeutrality-06!08!25Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2006 August Telstra Travail T3-AFR-06!08!28Document2 pages2006 August Telstra Travail T3-AFR-06!08!28Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2005 Nov Companies Open Path To Customer InnovationDocument2 pages2005 Nov Companies Open Path To Customer InnovationJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumers Put at End of The Queue - BusinessDocument3 pagesConsumers Put at End of The Queue - BusinessJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2004 Nov Age-Old-04-11-20Document2 pages2004 Nov Age-Old-04-11-20Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2004 Sept Club Good AFR-Education-04!09!20Document3 pages2004 Sept Club Good AFR-Education-04!09!20Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- Australian Financial ReviewDocument3 pagesAustralian Financial ReviewJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2004 Mar 22 System Blocks Better Health CareDocument5 pages2004 Mar 22 System Blocks Better Health CareJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- Campus May 19Document1 pageCampus May 19Joshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- The Case For Credit Card Reform: A Primer For Students: Joshua Gans University of MelbourneDocument6 pagesThe Case For Credit Card Reform: A Primer For Students: Joshua Gans University of MelbourneCore ResearchPas encore d'évaluation

- Australian Financial ReviewDocument3 pagesAustralian Financial ReviewJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 1997 Jun The Inventive AlternativeDocument3 pages1997 Jun The Inventive AlternativeJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2000 Aug 1 Stephen King NovelDocument3 pages2000 Aug 1 Stephen King NovelJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 1998 Jan When Being First DoesnDocument3 pages1998 Jan When Being First DoesnJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- 2003 August Innovation NationDocument4 pages2003 August Innovation NationJoshua GansPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- A Critical Analysis On The Role of The Chinese in The Development of Philippine EconomyDocument5 pagesA Critical Analysis On The Role of The Chinese in The Development of Philippine EconomyAlexis0% (1)

- Urban Agriculture and Food Security Initiatives in CanadaDocument107 pagesUrban Agriculture and Food Security Initiatives in CanadaHatzopoulosIoannis100% (2)

- Rayanne Ramdass Moore MENG 1013 Individual PaperDocument7 pagesRayanne Ramdass Moore MENG 1013 Individual PaperRayanne MoorePas encore d'évaluation

- RDO No. 32 - Quiapo-Sampaloc-San Miguel-Sta MesaDocument713 pagesRDO No. 32 - Quiapo-Sampaloc-San Miguel-Sta MesaJasmin Regis Sy50% (6)

- White Paper HealthCare MalaysiaDocument28 pagesWhite Paper HealthCare MalaysiaNamitaPas encore d'évaluation

- New U LI Cable Support System Catalogue 2019Document185 pagesNew U LI Cable Support System Catalogue 2019muhamad faizPas encore d'évaluation

- Secretary Industries & Managing Director - KSIDC LTD: Alkesh SharmaDocument28 pagesSecretary Industries & Managing Director - KSIDC LTD: Alkesh SharmaMurali KrishnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers LimitedDocument63 pagesGarden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers LimitedSRARPas encore d'évaluation

- Four Steps To Writing A Position Paper You Can Be Proud ofDocument6 pagesFour Steps To Writing A Position Paper You Can Be Proud ofsilentreaderPas encore d'évaluation

- Recruitment in BpoDocument14 pagesRecruitment in BpoMalvika PrajapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- André Gorz Autonomy and Equity in The Post-Industrial AgeDocument14 pagesAndré Gorz Autonomy and Equity in The Post-Industrial Ageademirpolat5168Pas encore d'évaluation

- The History of The Spanish EmpireDocument2 pagesThe History of The Spanish Empireapi-227795658Pas encore d'évaluation

- I Defenition of Currency 2Document17 pagesI Defenition of Currency 2HAPSAH HARIANTIPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Analysis Toy WorldDocument11 pagesCase Analysis Toy WorldNiketa Jaiswal100% (1)

- Details of Principal Inputs/ Capital Goods Sr. No. Input Materials/ Capital Goods HSN Exemption Notification Rate of GST CT ST Igst CessDocument3 pagesDetails of Principal Inputs/ Capital Goods Sr. No. Input Materials/ Capital Goods HSN Exemption Notification Rate of GST CT ST Igst Cessgroup3 cgstauditPas encore d'évaluation

- Admission To Undergraduate Programmes NtuDocument2 pagesAdmission To Undergraduate Programmes Ntuyen_3580Pas encore d'évaluation

- Qualified Contestable Customers - January 2022 DataDocument59 pagesQualified Contestable Customers - January 2022 DataDr. MustafaAliPas encore d'évaluation

- Rohit's Investigatory Project - Docx PhysicsDocument22 pagesRohit's Investigatory Project - Docx PhysicsSaurav Soni100% (1)

- Tata SteelDocument8 pagesTata SteelKamlesh TripathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ecological Solid Waste DraftDocument27 pagesEcological Solid Waste DraftKhryz CallëjaPas encore d'évaluation

- Report User DSDocument99 pagesReport User DSPrabuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Byzantine Empire Followed A Tradition of Caesaropapism in Which The Emperor Himself Was The Highest Religious Authority Thereby Legitimizing Rule Without The Need of Any Formal InstitutionDocument2 pagesThe Byzantine Empire Followed A Tradition of Caesaropapism in Which The Emperor Himself Was The Highest Religious Authority Thereby Legitimizing Rule Without The Need of Any Formal Institutionarindam singhPas encore d'évaluation

- David Robinson Curse On The Land History of The Mozambican Civil WarDocument373 pagesDavid Robinson Curse On The Land History of The Mozambican Civil WarLisboa24100% (2)

- Dalwadi SirDocument4 pagesDalwadi SirVinod NairPas encore d'évaluation

- A Research Report ON "Perception of Consumer Towards Online Food Delivery App"Document43 pagesA Research Report ON "Perception of Consumer Towards Online Food Delivery App"DEEPAKPas encore d'évaluation

- EI2 Public Benefit Organisation Written Undertaking External FormDocument1 pageEI2 Public Benefit Organisation Written Undertaking External Formshattar47Pas encore d'évaluation

- Haier CompanyDocument11 pagesHaier CompanyPriyanka Kaveria0% (1)

- Letter - Offer of Earnest MoneyDocument2 pagesLetter - Offer of Earnest MoneyIpe Closa100% (1)

- Chapter 7 AbcDocument5 pagesChapter 7 AbcAyu FaridYaPas encore d'évaluation

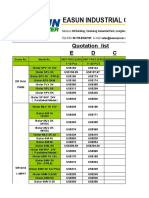

- Quotation List E D C: Series No. Model No. Unit Price (Usd) Unit Price (Usd) Unit Price (Usd)Document4 pagesQuotation List E D C: Series No. Model No. Unit Price (Usd) Unit Price (Usd) Unit Price (Usd)Lucian StroePas encore d'évaluation