Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Risos - Vidal V Comelec

Transféré par

上原クリスTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Risos - Vidal V Comelec

Transféré par

上原クリスDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Risos Vidal v Comelec

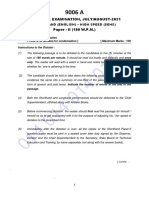

G.R. No. 206666, January 21, 2015

TOPIC: Powers and functions of the President | Special Powers | Executive clemencies

Petitioner: ATTY. ALICIA RISOS-VIDAL, ALFREDO S. LIM PETITIONER-INTERVENOR,

Respondents: COMELEC and Joseph Ejercito Estrada

Ponente: Leonardo-De Castro, J., Certiorari

FACTS

- Sept 12, 2007 - the Sandiganbayan convicted former President Estrada of plunder, sentenced to reclusion perpetua, civil interdiction

during period of sentence, perpetual absolute disqualification.

- Oct 25, 2007 pres Arroyo extended executive clemency, by way of pardon, to former President Estrada

- WHEREAS, this Administration has a policy of releasing inmates who have reached the age of seventy (70),

WHEREAS, Joseph Ejercito Estrada has been under detention for six and a half years,

WHEREAS, Joseph Ejercito Estrada has publicly committed to no longer seek any elective position or office,

IN VIEW HEREOF and pursuant to the authority conferred upon me by the Constitution, I hereby grant executive clemency to JOSEPH

EJERCITO ESTRADA, convicted by the Sandiganbayan of Plunder and imposed a penalty of Reclusion Perpetua. He is hereby

restored to his civil and political rights.

The forfeitures imposed by the Sandiganbayan remain in force and in full, including all writs and processes issued by the

Sandiganbayan in pursuance hereof, except for the bank account(s) he owned before his tenure as President.

Upon acceptance of this pardon by JOSEPH EJERCITO ESTRADA, this pardon shall take effect.

- Oct 26, 2007 Pres Estrada received and accepted the pardon by signing beside his handwritten notation thereon

- Nov 30, 2009 Pres Estrada filed a COC for President, and 3 peititons for disqualification were filed at the Comelec, which dismissed

the petitions on grounds that

(i) the Constitutional proscription on reelection applies to a sitting president; and

(ii) the pardon granted to former President Estrada by former President Arroyo restored the formers right to vote and be voted for a

public office.

- May 10, 2010 Pres Estrada got only second highest number of votes

- One of the abovementioned petitioners that sought to disqualify Pres Estrada filed a petition for certiorari at the SC, but it was

dismissed due to mootness

- Oct 2, 2012 Pres Estrada filed COC for post of Mayor of Manila

- Jan 24, 2013, Atty Risos-Vidal filed a petition for disqualification for conviction of plunder disqualified by the Local Government

Code

SECTION 40. Disqualifications. - The following persons are disqualified from running for any elective local position:

(a) Those sentenced by final judgment for an offense involving moral turpitude or for an offense punishable by one (1) year or more

of imprisonment, within two (2) years after serving sentence;

Sec. 12, Omnibus Election Code:

Section 12. Disqualifications. - Any person who has been declared by competent authority insane or incompetent, or has been

sentenced by final judgment for subversion, insurrection, rebellion, or for any offense for which he has been sentenced to a

penalty of more than eighteen months or for a crime involving moral turpitude, shall be disqualified to be a candidate and to

hold any public office, unless he has been given plenary pardon or granted amnesty.

April 1, 2013 petition was dismissed because the Comelec had earlier ruled that [former President Estradas] right to seek public

office has been effectively restored by the pardon the petitioner hasnt brought forward basis to reverse it

- May 13, 2013 While the petition was pending, Pres Estrada was elected as Mayor

- June 7, 2013 Mayor Lim, Pres Estradas opponent intervened in the case, agreeing that Pres Estrada is disqualified to run as the

pardon granted to the latter failed to expressly remit his perpetual disqualification; all the votes obtained by the latter should

be declared stray, and, being the second placer with 313,764 votes to his name, he (Lim) should be declared the rightful

winning candidate

ISSUE: whether or not the COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction in ruling that

former President Estrada is qualified to vote and be voted for in public office as a result of the pardon granted to him by

former President Arroyo.

HELD: NO

WHEREFORE, the petition for certiorari and petition-in-intervention are DISMISSED. The Resolution dated April 1, 2013 of the

Commission on Elections, Second Division, and the Resolution dated April 23, 2013 of the Commission on Elections, En banc,

both in SPA No. 13-211 (DC), are AFFIRMED.

RATIO:

- Former President Estrada was granted an absolute pardon that fully restored all his civil and political rights, which naturally includes

the right to seek public elective office

- The wording of the pardon extended to former President Estrada is complete, unambiguous, and unqualified.

- The pardoning power of the President cannot be limited by legislative action.

- Section 19 of Article VII and Section 5 of Article IX-C, provides that the President of the Philippines possesses the power to grant

pardons, along with other acts of executive clemency,

Section 19. Except in cases of impeachment, or as otherwise provided in this Constitution, the President may grant reprieves,

commutations, and pardons, and remit fines and forfeitures, after conviction by final judgment.

He shall also have the power to grant amnesty with the concurrence of a majority of all the Members of the Congress.

xxxx

Section 5. No pardon, amnesty, parole, or suspension of sentence for violation of election laws, rules, and regulations shall be granted

by the President without the favorable recommendation of the Commission.

- the only instances in which the President may not extend pardon remain to be in: (1) impeachment cases;

(2) cases that have not yet resulted in a final conviction; and

(3) cases involving violations of election laws, rules and regulations in which there was no favorable recommendation coming from

the COMELEC.

Therefore, it can be argued that any act of Congress by way of statute cannot operate to delimit the pardoning power of the

President. (As ruled by the court in Monsanto v FActoran - a pardon, being a presidential prerogative, should not be

circumscribed by legislative action.)

- Doctrine of non-diminution or non-impairment of the Presidents power of pardon by acts of Congress, specifically through

legislation, - strongly adhered to by an overwhelming majority of the framers of the 1987 Constitution framers did not want

an exception from the pardoning power of the President in the form of offenses involving graft and corruption that would

be enumerated and defined by Congress through the enactment of a law. - Aside from the fact that it is a derogation of the

power of the President to grant executive clemency, it is also defective in that it singles out just one kind of crime. (34-4

votes amendment to delete phrase was approved)

- Petitioner invoked Articles 36 and 41 of the Revised Penal Code.

ART. 36. Pardon; its effects. A pardon shall not work the restoration of the right to hold public office, or the right of suffrage, unless

such rights be expressly restored by the terms of the pardon.

A pardon shall in no case exempt the culprit from the payment of the civil indemnity imposed upon him by the sentence.

ART. 41. Reclusion perpetua and reclusion temporal Their accessory penalties. The penalties of reclusion perpetua and reclusion

temporal shall carry with them that of civil interdiction for life or during the period of the sentence as the case may be, and

that of perpetual absolute disqualification which the offender shall suffer even though pardoned as to the principal penalty,

unless the same shall have been expressly remitted in the pardon.

- Justice Leonens dissent: agreed with Risos-Vidal that there was no express remission and/or restoration of the rights of suffrage

and/or to hold public office in the pardon granted to former President Estrada, as required by Articles 36 and 41 of the RPC.

that the aforementioned codal provisions must be followed by the President, as they do not abridge or diminish the

Presidents power to extend clemency. He opines that they do not reduce the coverage of the Presidents pardoning power.

- Articles 36 and 41 of the Revised Penal Code should be construed in a way that will give full effect to the executive clemency

granted by the President, instead of indulging in an overly strict interpretation that may serve to impair or diminish the

import of the pardon which emanated from the Office of the President

- Risos-Vidal relied heavily on the separate concurring opinions in Monsanto v. Factoran, Jr.[36] to justify her argument that an

absolute pardon must expressly state that the right to hold public office has been restored, and that the penalty of perpetual

absolute disqualification has been remitted.

- this is incorrect. The concurring opinions do not form part of the controlling doctrine nor to be considered part of the law of the land.

- the subsequent absolute pardon granted to former President Estrada effectively restored his right to seek public elective office. - by

reading Section 40(a) of the LGC in relation to Section 12 of the OEC.

- Section 12 of the OEC provides a legal escape from the prohibition a plenary pardon or amnesty. In other words, the latter

provision allows any person who has been granted plenary pardon or amnesty after conviction by final judgment of an

offense involving moral turpitude, inter alia, to run for and hold any public office, whether local or national position.

The third preambular clause of the pardon did not operate to make the pardon conditional.

- [w]hereas, Joseph Ejercito Estrada has publicly committed to no longer seek any elective position or office,

- the pardon itself does not explicitly impose a condition or limitation, considering the unqualified use of the term civil and political

rights as being restored.

- a preamble is not an essential part of an act as it is an introductory or preparatory clause that explains the reasons for the

enactment, usually introduced by the word whereas. Whereas clauses do not form part of a statute because, strictly

speaking, they are not part of the operative language of the statute.

- Where the meaning of a statute is clear and unambiguous, the preamble can neither expand nor restrict its operation much less

prevail over its text. If former President Arroyo intended for the pardon to be conditional on Respondents promise never to

seek a public office again, the former ought to have explicitly stated the same in the text of the pardon itself. (Comelec

resolution)

- the pardon granted to former President Estrada was absolute in the absence of a clear, unequivocal and concrete factual basis upon

which to anchor or support the Presidential intent to grant a limited pardon.

The COMELEC did not commit grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction in issuing the assailed Resolutions.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Miranda v Aguirre rules plebiscite needed to downgrade city statusDocument3 pagesMiranda v Aguirre rules plebiscite needed to downgrade city status上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Miranda v Aguirre rules plebiscite needed to downgrade city statusDocument3 pagesMiranda v Aguirre rules plebiscite needed to downgrade city status上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Lauren Berlant Cruel OptimismDocument354 pagesLauren Berlant Cruel OptimismEzequiel Zaidenwerg80% (15)

- Discussion Fair Trade ESLDocument3 pagesDiscussion Fair Trade ESLbizabt50% (2)

- Quezon City PTCA v. DEPED G.R. No. 188720 February 23 2016 1Document2 pagesQuezon City PTCA v. DEPED G.R. No. 188720 February 23 2016 1Kate Del PradoPas encore d'évaluation

- Province of North Cotabato V Government of The Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesProvince of North Cotabato V Government of The Republic of The PhilippinesFina SchuckPas encore d'évaluation

- Planters Products Inc V FertiPhil CorporationDocument2 pagesPlanters Products Inc V FertiPhil Corporation上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Search and Seizure GF CASESDocument7 pagesSearch and Seizure GF CASESAnonymous GMUQYq8Pas encore d'évaluation

- Holdings Vs NationalDocument2 pagesHoldings Vs NationalJanine FabePas encore d'évaluation

- 111 People v. Dela CruzDocument5 pages111 People v. Dela CruzCharles MagistradoPas encore d'évaluation

- Module Vi. Special Groups of Employees Libres V NLRCDocument29 pagesModule Vi. Special Groups of Employees Libres V NLRCYuri NishimiyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Davao Fruits Corporation vs. Associated Labor Union, 1993Document4 pagesDavao Fruits Corporation vs. Associated Labor Union, 1993Maribel Nicole LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- CORPORATION LAW CASES EXAMINEDDocument15 pagesCORPORATION LAW CASES EXAMINEDCheska Christiana SaguinPas encore d'évaluation

- AA Wills SuccessionDocument4 pagesAA Wills SuccessionKent Wilson Orbase AndalesPas encore d'évaluation

- 2169351-2014-Phil. Woman S Christian Temperance UnionDocument13 pages2169351-2014-Phil. Woman S Christian Temperance UnionChristine Ang CaminadePas encore d'évaluation

- Laperal v. Solid HomesDocument22 pagesLaperal v. Solid HomesDeo Aaron Xenos Literato100% (1)

- Acaac V AzcunaDocument3 pagesAcaac V AzcunaQuengilyn Quintos100% (1)

- Risos-Vidal vs. ComelecDocument4 pagesRisos-Vidal vs. ComelecAbbyElbamboPas encore d'évaluation

- 159 Beltran V MacasiarDocument2 pages159 Beltran V MacasiarDon King MamacPas encore d'évaluation

- Presidency and Removal PowerDocument1 pagePresidency and Removal PowerPatricia BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Defensor-Santiago v. RamosDocument1 pageDefensor-Santiago v. RamosSandy Marie DavidPas encore d'évaluation

- Javellana vs. Executive SecretaryDocument5 pagesJavellana vs. Executive SecretaryJohnny EnglishPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Registry Acts and EventsDocument1 pageCivil Registry Acts and EventsJian CerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Kalaw vs. Fernandez, G.R. No. 166357, Jan. 14, 2015Document1 pageKalaw vs. Fernandez, G.R. No. 166357, Jan. 14, 2015Charmila SiplonPas encore d'évaluation

- Mercado v. ManzanoDocument1 pageMercado v. Manzano上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Veneracion Vs MancillaDocument3 pagesVeneracion Vs MancillaFrancis AlbaranPas encore d'évaluation

- CSR Activities Icici Bank LimitedDocument14 pagesCSR Activities Icici Bank LimitedVidya Satish KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Tichangco Vs EnriquezDocument6 pagesTichangco Vs EnriquezKimberlyPlazaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jorge v. Mayor (1964), Deocampo, EH 202Document3 pagesJorge v. Mayor (1964), Deocampo, EH 202Jewel Vernesse Dane DeocampoPas encore d'évaluation

- PBCOM Vs CommissionerDocument2 pagesPBCOM Vs Commissioner上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Judicial Admissions Determine Ownership <40Document3 pagesJudicial Admissions Determine Ownership <40Judy Ann ShengPas encore d'évaluation

- White Light Corporation VDocument2 pagesWhite Light Corporation VAlfonso DimlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Senate Vs ErmitaDocument2 pagesSenate Vs ErmitaMarkDungoPas encore d'évaluation

- Statutory Construction Reviewer SummaryDocument47 pagesStatutory Construction Reviewer SummaryAya MrvllaPas encore d'évaluation

- Presidential authority to reorganize executive branch upheldDocument2 pagesPresidential authority to reorganize executive branch upheld上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Cybercrime Law Provisions ChallengedDocument7 pagesCybercrime Law Provisions ChallengedRhows BuergoPas encore d'évaluation

- President's veto power upheld by Supreme CourtDocument5 pagesPresident's veto power upheld by Supreme Court上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Chavez v. RomuloDocument5 pagesChavez v. RomuloMargo Wan RemolloPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Judges Association v. Prado (1993) - DIGESTDocument3 pagesPhilippine Judges Association v. Prado (1993) - DIGESTIsabelle AtenciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rutter v. EstebanDocument10 pagesRutter v. EstebanJenica Anne DalaodaoPas encore d'évaluation

- REPUBLIC Vs CA and PlazaDocument2 pagesREPUBLIC Vs CA and PlazaLeo TumaganPas encore d'évaluation

- Martinez Vs MorfeDocument6 pagesMartinez Vs Morfe上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Martinez Vs MorfeDocument6 pagesMartinez Vs Morfe上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Sanlakas V Angelo ReyesDocument3 pagesSanlakas V Angelo Reyes上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Tesda V CoaDocument2 pagesTesda V Coa上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- CW3 - 3Document2 pagesCW3 - 3Rigel Zabate54% (13)

- Manila Electric Co V Pasay Transportation IncDocument1 pageManila Electric Co V Pasay Transportation Inc上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument17 pagesUntitledanatheacadagatPas encore d'évaluation

- Slater Brief On Appeal As FiledDocument36 pagesSlater Brief On Appeal As FiledTHROnlinePas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Tuberculosis Society Executive Secretary Removal CaseDocument10 pagesPhilippine Tuberculosis Society Executive Secretary Removal CaseLeon Milan Emmanuel RomanoPas encore d'évaluation

- The United States Vs Juan PonsDocument3 pagesThe United States Vs Juan PonsMczoC.MczoPas encore d'évaluation

- Carolino V Senga (Article 4)Document17 pagesCarolino V Senga (Article 4)Bhie JaneePas encore d'évaluation

- Gonzales Vs Kalaw KatigbakDocument4 pagesGonzales Vs Kalaw KatigbakMark Joseph M. VirgilioPas encore d'évaluation

- Padilla vs. Congress CDDocument7 pagesPadilla vs. Congress CDClarisse Anne Florentino AlvaroPas encore d'évaluation

- Nerwin V PNOC, G.R. No. 167057, April 11, 2012 FactsDocument1 pageNerwin V PNOC, G.R. No. 167057, April 11, 2012 FactsKim Michael de JesusPas encore d'évaluation

- Review Center of The Philippines v. ErmitaDocument4 pagesReview Center of The Philippines v. ErmitajrvyeePas encore d'évaluation

- GR 101083 Oposa V Factoran Jr. July 30, 1993Document11 pagesGR 101083 Oposa V Factoran Jr. July 30, 1993Naro Venna VeledroPas encore d'évaluation

- PERSONS - Republic v. LorinoDocument2 pagesPERSONS - Republic v. LorinoJeffrey EndrinalPas encore d'évaluation

- Sereno Case DigestDocument4 pagesSereno Case DigestWingmannuuPas encore d'évaluation

- Valderama vs. MacaldeDocument19 pagesValderama vs. MacaldeAje EmpaniaPas encore d'évaluation

- 203 Torres v. GonzalesDocument2 pages203 Torres v. GonzalesAngela ConejeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Bambalan v. MarambaDocument1 pageBambalan v. Marambacmv mendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Documents - MX - Civrev Persons Ruiz V Atienza Force Intimidation ThreatDocument2 pagesDocuments - MX - Civrev Persons Ruiz V Atienza Force Intimidation ThreatryuseiPas encore d'évaluation

- Persons - M112 Silva V CADocument1 pagePersons - M112 Silva V CAYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Texas v. Johnson, IBP v. Atienza DigestsDocument1 pageTexas v. Johnson, IBP v. Atienza DigestsBinkee VillaramaPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 2 DigestDocument16 pagesWeek 2 DigestJerickson A. ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Digested - PPhil V SantiagoDocument2 pagesDigested - PPhil V SantiagonojaywalkngPas encore d'évaluation

- Solar Harvest vs. Davao Corrugated CartonDocument12 pagesSolar Harvest vs. Davao Corrugated CartonGloria Diana DulnuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Onas Vs JavillanoDocument5 pagesOnas Vs JavillanoPam MiraflorPas encore d'évaluation

- AM No. 02 11 10 SC PDFDocument6 pagesAM No. 02 11 10 SC PDFCherzPas encore d'évaluation

- Bengzon V Senate Blue CommitteeDocument2 pagesBengzon V Senate Blue CommitteeCarlota Nicolas VillaromanPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest - Week 5.3Document7 pagesCase Digest - Week 5.3Van John MagallanesPas encore d'évaluation

- New Case DigestDocument9 pagesNew Case DigestReyrhye RopaPas encore d'évaluation

- 69 - Digest - Bunag Vs CA - G.R. No. 101749 - 10 July 1992Document3 pages69 - Digest - Bunag Vs CA - G.R. No. 101749 - 10 July 1992Christian Kenneth TapiaPas encore d'évaluation

- US v. Felipe BustosDocument1 pageUS v. Felipe BustosJairus Adrian VilbarPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Risos Vidal v. COMELECDocument2 pages1 Risos Vidal v. COMELECDennisgilbert GonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- SAntiago V ComelecDocument4 pagesSAntiago V Comelec上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Romero V EstradaDocument4 pagesRomero V Estrada上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Ople V TorresDocument2 pagesOple V Torres上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Province of North Cotabato vs GRP explores extent of presidential peace powersDocument2 pagesProvince of North Cotabato vs GRP explores extent of presidential peace powers上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Resident Marine Mammals V Sec of EnergyDocument1 pageResident Marine Mammals V Sec of Energy上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Pelaez V Auditor GeneralDocument2 pagesPelaez V Auditor General上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Mercado v. ManzanoDocument2 pagesMercado v. Manzano上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Occena vs. COMELECDocument2 pagesOccena vs. COMELEC上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Ople V TorresDocument2 pagesOple V Torres上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Occena vs. ComelecDocument3 pagesOccena vs. Comelec上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Occena vs. ComelecDocument3 pagesOccena vs. Comelec上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Nitafan V Commissioner of Internal RevenueDocument1 pageNitafan V Commissioner of Internal Revenue上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Neri V Senate Committee On Accountability of Public Officers and InvestigationsDocument8 pagesNeri V Senate Committee On Accountability of Public Officers and Investigations上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Marcos V ManglapusDocument4 pagesMarcos V Manglapus上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- MMDA V Concerned Residents of Manila BayDocument2 pagesMMDA V Concerned Residents of Manila Bay上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Magallona V ErmitaDocument2 pagesMagallona V Ermita上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- Manila Prince Hotel V GSISDocument2 pagesManila Prince Hotel V GSIS上原クリスPas encore d'évaluation

- U.S Military Bases in The PHDocument10 pagesU.S Military Bases in The PHjansenwes92Pas encore d'évaluation

- HallTicket Us16286Document4 pagesHallTicket Us16286Yuvaraj KrishnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Adv N Disadv of Privatisation of Health Sector in IndiaDocument5 pagesAdv N Disadv of Privatisation of Health Sector in IndiaChanthini VinayagamPas encore d'évaluation

- Essay On Rabbit Proof FenceDocument6 pagesEssay On Rabbit Proof Fencepaijcfnbf100% (2)

- Democracy As A Way of LifeDocument12 pagesDemocracy As A Way of LifeGarrison DoreckPas encore d'évaluation

- The Indian Contract Act 1872: Essential Elements and Types of ContractsDocument3 pagesThe Indian Contract Act 1872: Essential Elements and Types of ContractsrakexhPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic of The Philippines Barangay General Malvar - Ooo-Office of The Punong BarangayDocument2 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Barangay General Malvar - Ooo-Office of The Punong BarangayBarangay Sagana HappeningsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pak301 Assignment No 1Document2 pagesPak301 Assignment No 1Razzaq MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Mamolang Written AnalysisDocument11 pagesMamolang Written AnalysisCHRISTIAN MAHINAYPas encore d'évaluation

- I. Heijnen - Session 14Document9 pagesI. Heijnen - Session 14Mădălina DumitrescuPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 Drug Awareness ProgramDocument2 pages2022 Drug Awareness ProgramBarangay HipodromoPas encore d'évaluation

- FILED 04 29 2016 - Brief For Defendant-Appellant With AddendumDocument227 pagesFILED 04 29 2016 - Brief For Defendant-Appellant With AddendumMetro Puerto RicoPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison Between Formal Constraints and Informal ConstraintsDocument4 pagesComparison Between Formal Constraints and Informal ConstraintsUmairPas encore d'évaluation

- By Paul Wagner: Introduction To Mchowarth'S FencingDocument8 pagesBy Paul Wagner: Introduction To Mchowarth'S FencingStanley BakerPas encore d'évaluation

- Sahitya Akademi Award Tamil LanguageDocument5 pagesSahitya Akademi Award Tamil LanguageshobanaaaradhanaPas encore d'évaluation

- LARR 45-3 Final-1Document296 pagesLARR 45-3 Final-1tracylynnedPas encore d'évaluation

- La Movida MadrilenaDocument13 pagesLa Movida Madrilenaapi-273606547Pas encore d'évaluation

- Week 2 - CultureDocument22 pagesWeek 2 - CulturePei Xin ChongPas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Career: Carlo AngelesDocument3 pagesProfessional Career: Carlo AngelesJamie Rose AragonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Hall - The Secret Lives of Houses Women and Gables in The 18 C Cape - ReducedDocument13 pagesHall - The Secret Lives of Houses Women and Gables in The 18 C Cape - ReducedAbhishek AndheePas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial ConflictsDocument3 pagesIndustrial Conflictsnagaraj200481Pas encore d'évaluation

- Maintaining momentum and ensuring proper attendance in committee meetingsDocument5 pagesMaintaining momentum and ensuring proper attendance in committee meetingsvamsiPas encore d'évaluation

- Cuban Missile Crisis Lesson Plan - StanfordDocument6 pagesCuban Missile Crisis Lesson Plan - Stanfordapi-229785206Pas encore d'évaluation

- Columbia Roosevelt Review 2012Document71 pagesColumbia Roosevelt Review 2012Sarah ScheinmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rhetorical Analysis of Sotomayor's "A Latina Judges Voice"Document4 pagesRhetorical Analysis of Sotomayor's "A Latina Judges Voice"NintengoPas encore d'évaluation

- Program On 1staugustDocument3 pagesProgram On 1staugustDebaditya SanyalPas encore d'évaluation