Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Sialkot

Transféré par

Syed Nadir Shah Bukhari0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

10 vues3 pagesmy sialkot city

Titre original

sialkot

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

TXT, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentmy sialkot city

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme TXT, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

10 vues3 pagesSialkot

Transféré par

Syed Nadir Shah Bukharimy sialkot city

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme TXT, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 3

I did not want to leave Sialkot city.

This was my home.

I was born and brought up here.

Why could not I, a Hindu, live in the Islamic State of Pakistan when there would be

hundreds of thousands of Muslims residing in India? True, the religion was the

basis of the partition.

But then both the Congress and the Muslim League, the main political parties, had

opposed the exchange of population.

People could stay wherever they were.

Then why on August 14, 1947, I was unwelcome at a place where my forefathers and

their forefathers had lived for decades.

Our family had other reasons to stay back.

Most patients of my father, a medical practitioner, were Muslims.

My best friend, Shafqat, with whom I had grown up, lived in Sialkot.

At his mere wish I had tattooed on my right arm, the Islamic insignia, crescent and

star.

I was a graduate in Persian.

Pakistan had declared Urdu as its official language with which I felt at home.

We had a large property and a retinue of servants.

Where would we go if we were to uproot ourselves? Then our spiritual guardian was

there.

It was not a superstition but our faith that the grave in our back garden was that

of a Pir who protected us and guided the family whenever it faced troubles.

How could we leave the Pir? The grave was our refuge.

We always found relief there.

Our Maa, whenever harassed or after her quarrel with our father, ran to the grave

for solace.

We, three brothers and one sister, bowed before the Pir every Thursday in reverence

and lit an earthen lamp.

It was our temple.

People of Sialkot were mild, austere and tolerant.

They were cast in a different mould.

Our religions or positions in life did not distance us from one another.

We numbered about a lakh, 70 percent Muslims and 30 percent Hindus, Sikhs and

Christians.

As far as I could remember, we had never experienced tension, much less communal

riots.

Our festivals, Diwali, Holi or Eid, were joint and most of us walked together in

mourning on the Moharram Day.

Even our businesses depended on our cooperative effort.

There was a mixture of owners and workers from both communities.

Sport goods were the main industry and many labourers worked at home with their

family to meet the order, given peace meal.

Manufacturing surgical instruments was another vocation which engaged many.

Such works had brought us together " Hindus and Muslims " in a common endeavour.

Yet, we had Hindus and Muslim mohallas, not by name but by the categorisation of

population of both communities.

Some people belonging to one community lived in the habitation of the other.

Many houses shared common wall.

It exhibited a sense of accommodation.

Even in other parts of the city, there was normal activity, people did not know "

nor did they care " who was Muslim or who was Hindu.

Women moved freely, a few in burqa, some in thick chaddar but most with just a

dupatta, a mere scarf-like cloth.

Every day was like any day and business was usual.

Even at height of agitation over the demand for Pakistan, Sialkot did not

experience any tension.

Probably, there were two or three processions like the ones the Congress party had.

There was burst of happiness when Pakistan came into being.

The Muslim population was at the top of the world.

Sikhs depressed.

Yet there was no tension, not even a twinge of enmity.

We spoke the same Punjabi.

The Punjabi we spoke in Sialkot had a peculiar accent.

I discovered this when I met Nawaz Sharif, then chief minister, for the first time

at Delhi after partition.

It took him no time to tell me that I was from Sialkot.

He said that the way in which I spoke Punjabi had a distinctive twang, a kind of

accent, which was confined to the Sialkotees.

But why only I, subcontinent's two great Urdu poets, Muhammed Iqbal and Faiz Ahmed

Faiz, who were from Sialkot, spoke Punjabi in the same way.

I had heard Iqbal one day at his mohalla, Imambara where Shafqat had taken me.

I was a child then and I never went near him out of fear.

Even otherwise I would not have approached him at that time because he was speaking

angrily in Punjabi.

All that I remembered about him was his huge girth, sitting on a stringed

charpai(cot) which almost touched the ground because of his weight.

Faiz Ahmed Faiz, the other renowned Urdu poet, became a good friend but after

partition we never met in Sialkot.

Probably the best in the Sialkotees flourished outside Sialkot.

Faiz spoke Punjabi with the Sialkotee's accent.

He was touchy about his Urdu pronunciation and gave up Urdu poetry for some time to

switch over to Punjabi.

He told me once that he did so because the Urdu circles made fun of his

pronunciation.

His much-talked trip to Lucknow was when he went there to meet a poet, Majaz, who

would say ji han (yes please), in response while Faiz replied han ji, han ji', the

typical way of Punjabis to say 'yes'.

Poets are primarily saints.

But saints are real saints.

Our city had honoured the visit of Guru Nanak Dev, founder of Sikh religion, to

Sialkot.

He was on his way to Medina and by building a Gurdwara stopped at our city for a

night.

Scores of years before partition, Puran Bhagat, a well-known devotee, came to our

city and healed many patients.

We had dug a well in his memory.

The city had also its ugly side.

A dutiful son, Sharvan Kumar, became defiant when he entered Sialkot.

He asked his blind parents, whom he had hauled across India for months, to pay him

for his labour.

Yet the city's innate goodness asserted itself at the time of partition.

Some tension was natural before the announcement of the Radcliffe Boundary Award "

delineating lines between India and Pakistan.

But there was not a single incident of violence.

Even otherwise, everyone had taken it for granted that Sialkot would be part of

Pakistan.

The Jain mohalla in the heart of the city did not go to sleep for nights.

Its fears were allayed when the Muslim localities surrounding the mohalla assured

protection.

By then Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founder of Pakistan, had made the famous

statement: "You are free, you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to

your mosques or to any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan.

You may belong to any religion or caste or creed " that has nothing to do with the

fundamental principle that we are all citizens of one state.

Now I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal and you will find that

in course of time, Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be

Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is a personal faith of each

individual but in political sense as citizens of the state.

" The categorical assurance made all the difference.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Black Friday - The True Story of - S Hussain ZaidiDocument222 pagesBlack Friday - The True Story of - S Hussain ZaidiAshwin Muthu67% (3)

- CeltsDocument156 pagesCeltsEngin Beksac100% (6)

- The Chronicles of Sant Gajanan Maharaj of ShegaonDocument127 pagesThe Chronicles of Sant Gajanan Maharaj of ShegaonShanmukha Kinkarra100% (3)

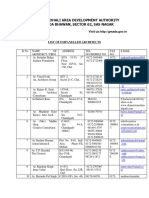

- List of Empanelled Architects MohaliDocument6 pagesList of Empanelled Architects MohaliCharlesPas encore d'évaluation

- Class 8 SST Test SolutionDocument44 pagesClass 8 SST Test SolutionChandan Kumar SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Sayings of Sri RamakrishnaDocument3 pagesSayings of Sri RamakrishnamukadePas encore d'évaluation

- Is 14959 2 2001 PDFDocument13 pagesIs 14959 2 2001 PDFGarima GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bse 20171213Document51 pagesBse 20171213BellwetherSataraPas encore d'évaluation

- IES - 2016 (TEST SERIES - 16 To 19) : Result - Electrical EngineeringDocument50 pagesIES - 2016 (TEST SERIES - 16 To 19) : Result - Electrical EngineeringVikas GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- 14 - Training Schedule Dated 07.04.2016Document54 pages14 - Training Schedule Dated 07.04.2016atingoyal1Pas encore d'évaluation

- I Point To IndiaDocument6 pagesI Point To IndiaSatyendra Nath DwivediPas encore d'évaluation

- Vaastu in Delhi - Palmistry in Delhi - Numerology in DelhiDocument5 pagesVaastu in Delhi - Palmistry in Delhi - Numerology in Delhifortune trioPas encore d'évaluation

- Punjab University (PU) - Spirituality and Workplace Stress Management PDFDocument10 pagesPunjab University (PU) - Spirituality and Workplace Stress Management PDFBeema ShihabPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 - Chapter 3 PDFDocument34 pages10 - Chapter 3 PDFMayank Kumar SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Formative Assessment 3 English 9Document2 pagesFormative Assessment 3 English 9Ankoosh MohammadPas encore d'évaluation

- NIOS Indian Culture - Heritage PDFDocument338 pagesNIOS Indian Culture - Heritage PDFUtkarsh MahulikarPas encore d'évaluation

- ProductionDocument49 pagesProductionbitrasurendrakumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Samskara PDFDocument6 pagesSamskara PDFtechzones0% (1)

- Fair & LovelyDocument7 pagesFair & LovelyTaohid Khan100% (1)

- Introduction To World Religions Quiz Senior High Lesson 3Document2 pagesIntroduction To World Religions Quiz Senior High Lesson 3King of the Hil100% (3)

- MagazineDocument84 pagesMagazineArnatUtkPas encore d'évaluation

- You Are Already Enlightened.: Sayings of Sri Bhagavan Ramana MaharshiDocument15 pagesYou Are Already Enlightened.: Sayings of Sri Bhagavan Ramana MaharshiiinselfPas encore d'évaluation

- Academia Kdp-Sample ORIGINS OF CHITPAVAN BRAHMINS PDFDocument22 pagesAcademia Kdp-Sample ORIGINS OF CHITPAVAN BRAHMINS PDFShiva NagriPas encore d'évaluation

- Important History of ArakanDocument4 pagesImportant History of ArakanRick HeizmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Daughter's Right of InheritanceDocument20 pagesDaughter's Right of InheritanceShivangi PorwalPas encore d'évaluation

- O E P L: Product PortfolioDocument3 pagesO E P L: Product PortfolioAnkit GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Data Highlights: The Scheduled Castes Census of India 2001: Andhra PradeshDocument4 pagesData Highlights: The Scheduled Castes Census of India 2001: Andhra PradeshChandan KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Blood Relations RSDocument33 pagesBlood Relations RSSrikanthrao SanthapurPas encore d'évaluation

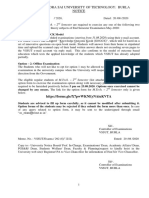

- Veer Surendra Sai University of Technology: Burla NoticeDocument3 pagesVeer Surendra Sai University of Technology: Burla NoticeTathagat TripathyPas encore d'évaluation

- Mumbai Port Civil Contractors PDFDocument2 pagesMumbai Port Civil Contractors PDFParth DamaPas encore d'évaluation