Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Cripe T 172010

Transféré par

Surender SinghTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Cripe T 172010

Transféré par

Surender SinghDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

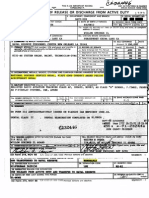

IN THE GAUHATI HIGH COURT

(THE HIGH COURT OF ASSAM; NAGALAND; MEGHALAYA; MANIPUR;

TRIPURA; MIZOAM AND ARUNACHAL PRADESH)

Criminal Petition No. 17/2010

MCLEOD RUSSEL INDIA LIMITED,

A Company incorporated under the provisions of the

Companies Act, 1956 and having its Registered Office

situated at 4, Mangoe Lane, Surendra Mohan Ghosh

Sarani, Kolkata-700001 and owns various Tea Estates in the

State of Assam including a Tea Estate in the name and style

of Namdang Tea Estate situated at Margherita, under P.S.

Margherita, in the District of Tinsukia, Assam. Represented

by Sri Baldeep Singh, the Senior Manager, Namdang Tea

Estate, P.O. & T.O. Margherita, in the District of Tinsukia,

Assam-786181.

- Petitioner

- Versus -

1. THE STATE OF ASSAM

2. THE OFFICER-IN-CHARGE,

Margherita Police Station,

P.O. & P.S. Margherita,

Dist. Tinsukia, Assam.

3. SRI ASHUTOSH TALUKDAR,

Son of Late Kagendra Nath lTalukdar,

R/O Namdang Tea Estate,

P.O. & P.S. Margherita,

Dist. Tinsukia, Assam.

- Respondents

BEFORE

THE HONBLE MR. JUSTICE I A ANSARI

Advocates present:

For the petitioner : Mr. D. Baruah, Mr. K Saharia,

Mr. P.P. Das,

Ms. S. Baruah,

For the respondent : Mr. D. Das, Addl. Public Prosecutor,

Assam.

For the Opp. Party. No.3 : Mr. J.M. Choudhury, Senior Advocate.

Mr. R.C. Paul, Mr. C Phukan,

Ms. S Roy,

Date of hearing : 11-04-2012

Date of judgment : 30-04-2012

Page 2

JUDGMENT & ORDER

Fairness of trial does not mean that the trial has to be fair to the

accused alone. Equally important is that the trial is fair to the person

aggrieved or whose near and dear ones are aggrieved. When police

registers a case, the State assumes the responsibility of conducting an

investigation. Having assumed the responsibility of investigating the truth

or veracity of the allegations, which the police receive, the State cannot act,

nor can its Investigating agency act, without a sense of impartiality. It is

not merely a trial, which has to be impartial. No less important it is that the

investigation, too, is impartial. Fairness of trial will carry with it the

fairness of investigation and fairness of investigation will carry with it the

impartiality in investigation, besides the investigation being efficient, un-

biased, not aimed at helping either the prosecution or the defence. In

short, an investigation must not suffer from any ulterior motive or hidden

agenda to either help a person or harm a person. This is the principle,

which Article 21 of the Constitution of India, read with Article 14 thereof,

enshrines, when we say that our Constitution guarantees fair trial. (See

Rana Sinha @ Sujit Sinha vs The State of Tripura & Ors. reported in (2011) 5

GLR 388)

2. With the help of this application, made under Section 482 Cr.P.C.,

the petitioner, who is the informant of Margherita Police Station Case No.

111 of 2008 (Corresponding to GR Case No. 276 of 2008), under Sections

408/420 IPC, has sought for setting aside and quashing the order, dated

16-12-2009, passed by the learned Judicial Magistrate 1st Class, Margherita,

declining to direct further investigation into the said case, in terms of the

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 3

provisions of Section 173(8) Cr.P.C., on the grounds that cognizance had

already been taken, process has already been issued against the accused-

opposite party No. 3 herein, namely, Sri Ashutosh Talukdar, the accused-

opposite party No. 3 has already entered appearance and that Section 311

Cr.P.C. read with Section 319 Cr.P.C., give sufficient power to the Court to

unearth the truth and, in the context of the facts of the present case, no

order for further investigation, as has been sought for by the informant, is

necessary.

3. The material facts emerging from the record and leading to the filing

of the present application, under Article 482 Cr.P.C., are, in brief, set out as

under:

(i) The informant is a company incorporated under the

Companys Act, 1956, with its registered office at Kolkata and owns

various tea gardens, in the State of Assam, including a tea garden, which is

run under the name and style of Namdang Tea Estate, situated at

Margherita, in the district of Tinsukia.

(ii) The accused-opposite party No. 3 herein, namely, Sri

Ashutosh Talukdar, was initially appointed, on 12-11-1984, as office clerk,

in Grade-III, in Namdang Tea Estate of the petitioner company and, with

effect from 18-03-2000, he was posted as Head Clerk of Namdang Tea

Estate. Being the Head Clerk, the opposite party No. 3, according to the

petitioner, was entrusted with the duty to prepare vouchers for

disbursement of payments to different persons, his additional duty being

preparation and maintenance of cash books in the computer as well as in

printed version. The accused, as Head Clerk, according to the petitioner,

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 4

was also entrusted with the duty to not only prepare vouchers, but make

payments.

(iii) Describing the manner in which the cash books, in computer

as well as in printed version, are maintained and various amounts, which

were disbursed to the third parties, the petitioner states that based on

approximate amounts payable by the said tea estate to various persons,

cash is withdrawn from the bank by the said tea estate and kept in the safe,

which remains in the custody of the Manager of the said tea estate, the said

safe of the petitioners tea estate being operated jointly with two different

keys at a time; while one key remains with the Manager of the said tea

estate, the other is kept by the Head Clark and that the Head Clark takes

out cash from the safe, in the presence of Manager, according to the

requirement of a given day. The cash, lying in the safe, is either withdrawn

on the same day or the subsequent day by the Head Clark as per

exigencies. The cash is withdrawn on the basis of the vouchers, which the

Head Clark prepares, and the amounts, mentioned in the vouchers, are

entered into the computer of the said tea estate and, upon making entry in

this regard, the computer generates a cash book (in the printed form) and,

thereafter, the printed cash book is signed by the Manager.

(iv) The informant companys auditor, namely, M/S BM Chatrath

and Company, found, upon conducting audit of the accounts of Namdang

Tea Estate, that the accused, as Head Clark, had manipulated the cash

books, which he was entrusted to prepare and maintain, and

misappropriated huge amount of money. The manipulation as well as

misappropriation, done by the accused, came to be unearthed by

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 5

conducting audit by one Sri Tejash Kr. Bhattacharjee, one of the auditors of

M/S BM Chatrath and Company, the process of manipulation resorted to

by the accused being that he manipulated the entries by showing, in the

computer system, cash payments of higher amounts than the amounts

actually paid. The consequence was that the cash entries, made in the

computer, were larger than that of the physical cash book, which the

accused himself had maintained, and, during the audit, the total of such

entries, made in the computer, were found to be different and varying

from the days total of cash payments in the cash book maintained by the

accused. It was also found, according to the informant, that the accused

had fraudulently prepared different cash books with missing entries and

wrong total of payments and produced the same before the Manager. The

auditor also found that false and fictitious entries had been made in the

computer system, which were not backed by relevant vouchers.

(v) The manipulation, committed by the accused, was revealed

when the auditors checked the printed cash book signed by the Manager.

The modus operandi of the accused, according to the informant, was thus:

The days total of cash payments, in the cash copies, were manipulated by

showing a higher total disbursement than the actual amounts paid and a

lower cash balance and thereby the requirement for cash were inflated.

Under such circumstances, the auditors counter-checked the entries of cash

payments in the system and found that the number of cash entries,

appearing in the system, were more as compared to the entries in the cash

book (in physical form), signed by the Manager, and the total of the extra

entries, appearing in the system, exactly matched with the difference

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 6

found in the days total of cash payments in the copies of cash book signed

by the Manager. This reflected that the accused, who had been entrusted

with the responsibility to prepare cash book and produce the same before

the Manager for latters signature, had fraudulently prepared different

cash books with missing entries and wrong total for payment and

produced the same before the Manager. All the additional entries of cash

payments, appearing in the cash book, in the computer system (and not in

printed form), were not supported by any voucher whatsoever, the entries,

thus, being all fake and willfully inserted in the system to cover up the

difference between the actual and enhanced cash expenses. The accused

also deleted/suppressed, in the system, the fake entries and the print-outs

of the cash book, showing genuine cash expenditure, in the entries,

suppressing the voucher, were given, in the printed form, by the Head

Clark to the Manager and he (accused) got the latters signatures obtained

thereon. However, the days total, in the system, being not changeable in

the system, remained unaltered in the printed cash book copies signed by

the Manager. As an illustration, the informant, while describing the modus

operandi of the accused, states that the accused, in maintaining and

preparing the cash book in the computer, would enter 100 entries of which

10 entries would be fraudulent and fictitious entries. While printing out

the said cash book prepared in the computer, the accused manipulated the

system, wherein only 90 entries would be mentioned; however, the total of

the 90 entries, which were reflected in the printed version of the cash book,

and the 100 entries, which were reflected in the cash book maintained in

the computer system, the total would always remain the same. In other

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 7

words, the total of 100 payment vouchers and the total of 90 genuine

payment vouchers, maintained in the printed form, in the cash book,

would be the same. The extra amount, (i.e. the total 10 fraudulent

vouchers) so drawn out from the safe, were misappropriated by the

accused. By this way, the accused had misappropriated an amount of Rs.

25,40,137.44p belonging to the petitioner.

(vi) Upon the report, so supported by the auditors, a First

Information Report was lodged with Margherita Police Station, which

came to be registered, as indicated above, as Margherita Police Station

Case No. 111 of 2008.

(vii) Following the registration of the FIR, the investigating officer

concerned seized, on various occasions, following documents:

(i) On 27.06.2008, the following documents were seized:-

(a) One Safe Book of Namdang Tea Estate containing Reg. NO.1 to

98.

(b) One Audit Report of Namdang Tea Estate done by M/s B. M.

Chatrath & Co., Chartered Accountant for the financial year

2007-08.

(c) One Audit Report of Namdang Tea Estate done by M/s

B.M.Chatrath & Co., Chartered Account for th period 2003-04 to

2006-07.

(d) Confession Letter written by Sri Ashutosh Talukdar addressing

the Acting Manager, Namdang Tea Estate alongwith list of

witnesses, code and amount date wise.

(ii) On 25.08.2009, the Investigating Officer seized one draft copy

written by the Respondent No.3 addressed to Gopal Automobile,

Makum Road, Tinsukia.

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 8

(iii) On 10.08.2009, the Investigating Officer seized the following

documents:-

(a) One C.P.U. (Computer Processing Unit) where account records

were stored at Namdang Tea Estate w.e.f. 2004-05 to 2006-07

and 2008.

(b) One CD(Compact Disk) containing cash books of Namdang Tea

Estate w.e.f. 2004-05 to 2006-07 and 2008.

(viii) The officials of the informant company apprised the

investigating officer of the manner of maintenance of printed cash book,

wherein the Managers had put their signatures, and the fact that the

seizure of the printed cash book was necessary, because the same were

wider piece of evidence, for, without comparing the printed cash book,

signed by the Managers, with the cash book, maintained in the computer,

it was not possible to prove the offence, which, according to the informant,

the accused had committed. This apart, during the course of investigation,

Shri Tejesh Kumar Bhattacharjee, one of the auditors, who had conducted

the audit as well as the Managers, who had signed the cash book, were not

examined as witnesses and their attendance were never sought for by the

investigating officer, at any stage, during the course of investigation. The

charge-sheet also reveals, points out the petitioner, that the said persons

have not been mentioned as prosecution witnesses, though their evidence

would be very material for the purpose of proving the commission of

offence by the accused.

4. The petitioner company submits that the accused was not

interrogated by the investigating authority and was shown as absconder in

the charge-sheet. In this regard, it is also brought to the notice of this Court

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 9

by the petitioner that the accused had filed as many as four applications

for pre-arrest bail, under Section 438 Cr.P.C., in the High Court, but all the

said applications were rejected and in the last Bail Application No.

2955/2009, the Court had, while rejecting the bail application, directed the

accused to surrender before the Sub-Divisional Judicial Magistrate,

Margherita, within a period of 14 days. The accused did not, however,

surrender contrary to the directions so issued. The informant, through its

Manager, filed an application, in the Court of the learned Sub-Divisional

Judicial Magistrate, Margherita, bringing to the notice of the learned Court

below the directions, which had been passed in Bail Application No.

2955/2009. However, the learned Sub-Divisional Judicial Magistrate,

Margherita, disposed of the said petition, filed by the Manager of the

informant company, by observing, in the order, dated 20-08-2009, that as

the accused person had neither surrendered nor has he been produced

before the Court, the Court could do nothing in respect of appearance of

the accused.

5. It is alleged by the informant company that the accused and the

investigating officer knew each other. They knew that in view of the order

passed by this Court in Bail Application No. 2955/2009, the accused would

not be granted bail and yet, in perfunctory and haphazard manner, the

investigating authority submitted charge-sheet against the accused, on 13-

09-2009, showing him as absconder. The said charge-sheet was taken note of

by the learned Magistrate on 23-10-2009 and the cognizance of offences

under Sections 408/420 IPC was taken and, having taken note of the fact

that the accused was an absconder, the learned Sub-Divisional Judicial

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 10

Magistrate, vide his order, dated 23-10-2009, transferred the case to Shri A

Deuri, learned Judicial Magistrate, 1st Class, Margherita, for disposal. On

29-10-2009, the accused, who had all along been absconding, appeared in

the trial Court and sought for bail even though no summon had been

issued by the learned trial Court and the learned trial Court, without

considering the earlier rejection of the application for pre-arrest bail and

also the fact that the direction given by the order, dated 24-07-2009, passed,

in Bail Application No. 2955/2009, by the High Court, to surrender in the

Court of the Sub-Divisional Judicial Magistrate, Margherita, had not been

complied with by the accused, granted bail to the accused on the ground

that the accused had appeared before the Court to face trial and fixed the

case, on 25-11-2009, for copy.

6. The informant came to learn, on 25-11-2009, about the filing of the

charge-sheet and, immediately, thereafter, on 03-12-2009, an application was

filed, on behalf of the informant, under Section 156(3) Cr.P.C., seeking

further investigation and, in this application, the informant stated that the

petitioner had reason to believe that it was for reasons other than bona fide

that the investigating officer had conducted the investigation in the most

perfunctory manner. A counsel, appearing on behalf of the informant-

petitioner, had also requested the learned trial Court to allow him to assist

the Public Prosecutor, who has to conduct a session triable case.

7. By order, dated 16-12-2009, the learned trial Court, as indicated

above, has rejected the petition made under Section 156(3) and also the

prayer made for allowing the petitioners counsel to assist the Public

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 11

Prosecutor on the ground that it is the Public Prosecutor, who has to

conduct a session triable case.

8. Four questions, which have arisen for determination in the present

case, are as under:

(i) Whether the Magistrate, after taking cognizance of a case upon a

Police Report, has the power and authority to direct further

investigation on an Application being filed by the informant or de

facto complainant?

(ii) Whether the Courts power, under Section 311 and Section 319, can

be effective substitute for further investigation?

(iii) Whether Section 302 read with Section 301 of the Code of Criminal

Procedure, 1973, envisages that for grant of leave from a Magistrate

for a private lawyer to appear before the Magistrate, a No Objection

is required from the Public Prosecutor?

(iv) Whether in the facts and circumstances of the instant case, a further

investigation is called for?

9. I have heard Mr. D Baruah, learned counsel for the informant-

petitioner, and Mr. D Das, learned Additional Public Prosecutor, Assam. I

have also heard Mr. JM Choudhury, learned Senior counsel, assisted by

Mr. C Phukan, learned counsel for the opposite party No. 3.

10. Appearing on behalf of the petitioner, Mr. Baruah, learned counsel,

submits that the facts, as narrated in the present application made under

Section 482 Cr.P.C. and the materials on record would go to show that the

investigating authority had conducted the investigation in a manner so as to

help the accused. The investigation was, according to Mr. Baruah, wholly

perfunctory, manipulated and unfair and, hence, based on such

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 12

perfunctory and unfair investigation, a charge-sheet has been laid. Mr.

Baruah, learned counsel, contends that as the investigation is wholly unfair,

it is necessary that unless the vital omissions, in the investigation, and the

unfairness thereof are removed by this Court by taking recourse to

appropriate provisions of law or else, the investigation would become a

precursor of miscarriage of justice.

11. Mr. Baruch points out that though the application, filed on behalf of

the petitioner, was made under Section 156(3), the fact remains that what

the petitioner had really sought for was a direction for further investigation

under Section 173(8) CrPC and, though the learned Magistrate may not

have the power to direct further investigation, because cognizance had

already been taken by him, there is no impediment, on the part of this

Court, to direct further investigation in exercise of its inherent power under

Section 482 CrPC.

12. Though Mr. Baruah does not, in specific term, challenges the fact

that no direction for further investigation could have been passed by the

learned Court below, because cognizance had already been taken, Mr.

Baruah contends that the limitation, which the learned Court below suffers

from, is not applicable to this Court inasmuch as this Court, under Section

482 Cr.P.C., is sufficiently empowered to direct further investigation and the

fact that the petitioner had made the application, seeking further

investigation, by mentioning Section 156(3) Cr.P.C., was immaterial and the

said petition ought to be treated as a petition seeking further investigation,

made under Section 173(8) Cr.P.C. and if this Court is satisfied that such a

direction is warranted in the facts and attending circumstances of the

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 13

present case, then, necessary directions be issued by invoking Section 482

CrPC.

13. Support for his submission that the High Court is empowered,

under Section 482 Cr.P.C., to direct further investigation, even after

cognizance has been taken by a Magistrate of an offence, Mr. Baruah places

reliance on the case of State of Punjab vs CBI, reported in (2011) 9 SCC 182,

and the case of Rana Sinha @ Sujit Sinha vs The State of Tripura & Ors.

reported in (2011) 5 GLR 388. Mr. Baruah, in this regard, also refers to the

case of Reeta Nag vs- State of West Bengal and others, reported in (2009) 9

SCC 129, and Randhir Singh Rana vs- State (Delhi Administration), reported

in (1997) 1 SCC 361.

14. In support of his contention that nomenclature, whereunder a

petition is filed, is irrelevant so long as the Court possesses the power, Mr.

Baruah refers to Pepsi Foods Limited vs- Special Judicial Magistrate (AIR

1998 SC 128).

15. On the basis of the authorities cited above, Mr. Baruah contends that

where an investigation is carried out in a manner, which is one sided or

unfair and/or when the investigation is tempered, the High Court has the

inherent power, under Section 482 Cr.P.C., to correct the miscarriage of

justice so that fair trial takes place and this can be achieved, in the present

case, by directing further investigation in terms of Section 173(8) Cr.P.C. The

power to issue such a direction can also be exercised, according to Mr.

Baruah, under Articles 226 and/or 227 of the Constitution of India.

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 14

16. Appearing on behalf of the accused-opposite party, Mr. J. M.

Choudhury, learned Senior counsel, has submitted that, in the case at

hand, the learned trial Court was wholly justified in declining to direct

further investigation, because the learned Court below had already taken

cognizance of offence and it had, therefore, no jurisdiction to direct further

investigation. The power to direct further investigation remains, according to

Mr. Choudhury, with a Magistrate so long as he has not accepted the police

report submitted by the police under Section 173(2) CrPC. This apart,

points out Mr. Choudhury, learned Senior counsel, the informant-

petitioners application, seeking further investigation was made under

Section 156(3) CrPC, which was not applicable to the facts of the case at

hand after the charge-sheet had already been submitted, for, Section 156(3)

empowers a Magistrate, contends Mr. Choudhury, to direct investigation

before he takes cognizance and not after he has already taken cognizance.

The investigation, in the present case, if unfair, can very well be, according

to Mr. Choudhury, cured by taking recourse to Section 311, read with

Section 319 CrPC, or else, it is the police, which may decide, in a given

case, to conduct further investigation if such an investigation is warranted.

17. While considering the present application, in the light of the

questions, which have arisen for determination, it needs to be carefully

noted that Mr. Baruah is wholly correct, when he submits that the

nomenclature or the Section, whereunder a particular application/ petition

is filed, in a Court, is immaterial. What is material is the substance or the

contents of the application/petition and the reliefs, which have been

sought for. The reference, made by Mr. Baruah, in this regard, to the case

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 15

of Pepsi Foods Limited Vs. Special Judicial Magistrate (AIR 1998 SC 128), is

not wholly misplaced. Viewed from this angle, it is clear that though the

petition was filed, in the present case, by the informant, under Section

156(3) Cr.P.C., seeking further investigation into the case aforementioned,

the fact of the matter remains that Section 156(3) Cr.P.C. does not deal with

further investigation, for, Section 156(3) Cr.P.C. empowers the Magistrate to

direct investigation before he takes cognizance of an offence in exercise of

his power under Section 190 Cr.P.C.; whereas further investigation by

investigating agency is provided in Section 173(8) Cr.P.C. and the question

of further investigation comes after the police, on completion of investigation,

has already submitted its report either in the form of charge-sheet or in the

form of final report informing the Court that there is no material at all or

insufficient material to put, on trial, the accused or any one named or

unnamed in the FIR.

18. A Division Bench of this Court, to which I was one of the parties, in

Rana Sinha @ Sujit Sinha (supra), has clearly drawn the distinction between

an investigation under Section 156(3) Cr.P.C. and further investigation under

Section 173(8) Cr.P.C. The Division Bench, in Rana Sinha @ Sujit Sinha

(supra), has also drawn the distinction between a further investigation and

re-investigation.

19. In the light of the fact that a further investigation is carried out by

police under Section 173(8) Cr.P.C., it needs to be noted that a Magistrate,

on his own, cannot order further investigation after he has already taken

cognizance of an offence on the basis of a police report. This position

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 16

clearly emerges from the case of Randhir Singh Rana (supra), wherein the

Court, while holding that a Magistrate cannot, on his own, direct further

investigation, if he has taken cognizance, observed thus:

11. The aforesaid being the legal position as discernible from the various

decisions of this Court and some of the High Courts, we would agree, as

presently advised, with Shri Vasdev that within the grey area to which we

have referred the Magistrate, of his own, cannot order for further

investigation. As in the present case the learned Magistrate had done so,

we set aside his order and direct him to dispose of the case either by framing

the charge or discharge the accused on the basis of materials already on

record. This will be subject to the caveat that even if the order be of

discharge, further investigation by the police on its own would be

permissible, which could even end in submission of either fresh charge-

sheet.

(Emphasis added)

20. The legal position, emerging from the case of Randhir Singh Rana

(supra), that a Magistrate, having taken cognizance of an offence, cannot

direct further investigation, came up for re-consideration in Reeta Nag

(supra) and, having analysed the law on the subject, the Supreme Court

has reiterated, in Reeta Nag (supra), its earlier decision, in Randhir Singh

Rana (supra), by taking the view that a Magistrate cannot, having taken

cognizance of an offence complained of, direct further investigation. The

relevant observations, appearing, in this regard, at Para 25 and 26, in Reeta

Nag (supra), read as under:

25. What emerges from the abovementioned decisions of this Court is that

once a charge-sheet is filed under Section 173(2) CrPC and either charge is

framed or the accused are discharged, the Magistrate may, on the basis of a

protest petition, take cognizance of the offence complained of or on the

application made by the investigating authorities permit further

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 17

investigation under Section 173(8). The Magistrate cannot suo motu direct

a further investigation under Section 173(8) CrPC or direct a

reinvestigation into a case on account of the bar of Section 167(2) of the

Code.

26. In the instant case, the investigating authorities did not apply for

further investigation and it was only upon the application filed by the de

facto complainant under Section 173(8) was a direction given by the

learned Magistrate to reinvestigate the matter. As we have already

indicated above, such a course of action was beyond the jurisdictional

competence of the Magistrate. Not only was the Magistrate wrong in

directing a reinvestigation on the application made by the de facto

complainant, but he also exceeded his jurisdiction in entertaining the said

application filed by the de facto complainant.

21. In the light of the position of law, as surfaced from the decision in

Randhir Singh Rana (supra) and Reeta Nag (supra), a Division Bench of this

Court clearly held, in Rana Sinha (supra), that a Magistrate cannot direct

further investigation on his own and if he cannot direct further investigation

on his own, it is not possible for him to hold that he can direct further

investigation on the basis of a petition filed by the informant, de facto

complainant, aggrieved person or the victim. The relevant observations,

appearing in this regard, read as under:

155. In the light of what has been observed option but to conclude and, in

fact, it is not even disputed that Ranbir Singh Rana (supra) lays down that

a Magistrate cannot, of his own, direct further investigation to be

conducted by the police if cognizance has already taken and the accused

has entered appearance. Rannbir Sinha Rana (supra) also clearly lays

down that a Magistrate cannot, in the name of advancing the cause of

justice, or to arrive at a just decision of the case, direct further investigation

to be conducted by the police if he does not, otherwise, have the power to

direct such further investigation meaning thereby that since a Magistrate

does not have the power to direct, on his own, further investigation after

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 18

cognizance has already been taken and the accused has entered

appearance, he cannot direct such further investigation of his own for the

purpose of advancing the cause of justice or even to arrive at a just

decision of the case.

156. No way, therefore, a Magistrate can direct further investigation of

his own and if he cannot direct further investigation of his own, it is not

possible to hold that he can direct such an investigation on the basis of

any petition filed by the informant, de facto complainant, aggrieved

person or the victim.

(Emphasis is added)

22. The question, therefore, which stares at us is: Whether the High Court,

in exercise of its power under Section 482 Cr.P.C., or in exercise of its power

under Article 226 and or 227 of the Constitution of India, can direct further

investigation if the facts of a case so warrant, even if cognizance of offence(s), as

revealed from the police report submitted under Section 173(2) CrPC, has already

been taken ?

23. While considering the question posed above, it needs to be noted

that the limitation, imposed on the power of a Magistrate, to direct further

investigation if he has taken cognizance of an offence, does not disable the

High Court to direct, in exercise of its power under Section 482 Cr.PC, or,

in a given case, even under Article 226 of the Constitution, further

investigation if so warranted in the facts of a given case. A complete answer

to this question has been given, in Rana Sinha (supra), which is reproduced

hereinbelow:

199. Considering the fact that we have already held that a court cannot,

on the basis of an application made by the informant, de facto complainant

or victim, order further investigation to be conducted by the police, when

the trial has already commenced, it logically follows that even if the

grievances of the son of the deceased couple, in the present case, had any

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 19

justification, the learned Court below had no power to direct further

investigation. The remedy of the present appellant, therefore, lied in

making, either an application under Section 482 of the Code or a writ

petition under Article 226 of the Constitution of India, seeking appropriate

direction to be issued by the High Court, in exercise of either its inherent

power under Section 482 or in exercise of its extra-ordinary jurisdiction

under Article 226, for further investigation. Whether the present appellant

could have made, in the fact situation of the present case, an application

under Section 482 or an application under Article 226 of the Constitution

of India and whether such an application could have been allowed, in the

context of the facts of the present case, is an aspect of the case, which we

would consider shortly.

*** *** ***

*** *** ***

203. What is, now, extremely important to note is that Article 227 vests

in the High Court the power of supervisory jurisdiction so as to keep the

courts and tribunals within the bounds of law. When a courts order is

correct and in accordance with law, the question of reversing such an order

in exercise of power under Article 227 does not arise. Same is the situation

at hand. Since the learned trial Court, in the present case, could not have

directed further investigation (as already held above) on the request of the

de facto complainant or the victim, such as, the present appellant, the

impugned order, declining to direct further investigation, cannot be said to

amount to refusal to exercise jurisdiction. If the case at hand warranted

further investigation, then, the remedy of the informant, de facto

complainant or the victim, such as, the present appellant, lied in

approaching the High Court either by making an application under

Section 482 of the Code or by making an application under Article 226

inasmuch as the High Court has, in appropriate cases, the power to direct

further investigation in exercise of its inherent power under Section 482

of the Code as well as in exercise of its extra-ordinary jurisdiction under

Article 226 of the Constitution of India if the facts of a given case so

warrant.

204. In fact, recognizing the power of the High Court, under Article 226,

to direct the State to get an offence investigated or further investigated,

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 20

the Supreme Court has held, in Kishan Lal (supra), that in a given

situation, the superior Court, in exercise of its Constitutional power,

namely, under Articles 226 and 32 of the Constitution of India, can direct

the State to get an offence investigated and/or further investigated by a

different agency. The relevant observations, made by the Supreme Court,

in this regard, read thus:

The investigating officer may exercise his statutory power of

further investigation in several situations as, for example, when

new facts come to his notice; when certain aspects of the matter

had not been considered by him and he found that further

investigation is necessary to be carried out from a different angle(s)

keeping in view the fact that new or further materials came to his

notice. Apart from the aforementioned grounds, the learned

Magistrate or the superior courts can direct further investigation, if

the investigation is found to be tainted and/or otherwise unfair or is

otherwise necessary in the ends of justice.

[Emphasis is added]

205. The order impugned, in the writ petition, could not have been said to

be an illegal order to the extent that the same declined further investigation

on the basis of the present appellants petition filed in the learned trial

Court. Seen in this light, when the impugned order was not illegal, the

question of reversing the order, by taking recourse to supervisory

jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226, could not have validly

arisen.

206. The question as to whether the present appellants grievances

against alleged unfair and manipulated investigation are justified or not

and, if justified, whether the learned Single Judge ought to have, in the facts

and attending circumstances of the present case, directed further

investigation, is a question, which needs to be, now, answered in this

appeal.

207. While considering the above aspect of this appeal, one has to also

bear in mind that the prayer made by a party, in any criminal or civil

trial, shall not be the sole determining factor as to whether a person is or

is not entitled to the relief, which he has sought for. If the law, on the

basis of the facts brought on record, requires a relief to be given to a

party, such a relief ought not to be disallowed merely because the party

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 21

has not specifically sought for such a relief unless, of course, the party

concerned himself refuses to receive such a relief.

*** *** ***

*** *** ***

212. A trial, based on such manipulated and unfair investigation, as in

the present case, would, if we may borrow the language in Babu Bhai

(supra), ultimately, prove to be precursor of miscarriage of criminal

justice. It is for such cases that the Supreme Court has pointed out and

observed, in Babu Bhai (supra), that if the investigation has not been

conducted fairly, such vitiated investigation cannot give rise to a valid

charge-sheet. In such a case the court would simply try to decipher the

truth only on the basis of guess or conjunctures as the whole truth would

not come before it. It will be difficult for the court to determine how the

incident took place. In no uncertain words, observed the Supreme Court,

in Babu Bhai (supra), that not only fair trial, but fair investigation too

forms part of constitutional rights guaranteed under Articles 20 and 21 of

the Constitution of India and, hence, investigation must be fair,

transparent and judicious inasmuch as a fair investigation is the

minimum requirement of rule of law and no investigating agency can be

permitted to conduct an investigation in tainted and biased manner. Held

the Supreme Court, in Babu Bhai (supra), that the court must interfere,

where non-interference by the court would, ultimately, result in failure of

justice.

(Emphasis is added)

24. Thus, notwithstanding the fact that a Magistrate is disabled from

directing further investigation once he has taken cognizance of offence on the

basis of a police report submitted under Section 173(2) Cr.PC., there is no

impediment, on the part of the High Court, to direct further investigation,

under Section 173(8), if the facts of a given case so warrant.

25. In short, the limitation, which is imposed on the power of a

Magistrate to direct further investigation if he has already taken cognizance,

does not apply to, or disable, the High Court from directing further

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 22

investigation, in a given case, if the facts of the case so warrant, by taking

recourse to Section 482 Cr.PC. A reference, in this regard, may be made to

the case of State of Punjab Vs. CBI, reported in (2011) 9 SCC 182, too. The

observations, appearing at Para 24 of State of Punjab (supra), read thus:

24. It is clear from the aforesaid observations of this Court that the

investigating agency or the court subordinate to the High Court exercising

powers under CrPC have to exercise the powers within the four corners of

CrPC and this would mean that the investigating agency may undertake

further investigation and the subordinate court may direct further

investigation into the case where charge-sheet has been filed under sub-

section (2) of Section 173 CrPC and such further investigation will not

mean fresh investigation or reinvestigation. But these limitations in sub-

section (8) of Section 173 CrPC in a case where charge-sheet has been filed

will not apply to the exercise of inherent powers of the High Court under

Section 482 CrPC for securing the ends of justice.

26. Though the informant, on coming to learn about the charge-sheet

having been laid, made an application, under Section 156(3) Cr.P.C.,

seeking further investigation on the grounds and reasons mentioned in the

said application, the fact remains that the learned trial Court had

committed no error by refusing to direct further investigation inasmuch as

the learned trial Court, having already taken cognizance of offence on the

basis of the charge-sheet already filed by the police, could not have directed,

in the light of Randhir Singh Rana (supra), Reeta Nag (supra) and Rana

Sinha (supra), further investigation. This would not, however, disable this

Court from directing further investigation into the case if the facts of the case

so warrants.

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 23

27. From the decision in Randhir Singh Rana (supra), Reeta Nag (supra)

and Rana Sinha (supra), it becomes transparent that in a case, where

investigation has been carried out in a one sided manner or when an

investigation has been carried out to favour a particular party or

investigation is tempered, the High Court, in exercise of its inherent power

under Section 482 Cr.P.C., and even under its supervisory jurisdiction

under Article 227 of the Constitution of India, and, in extraordinary cases,

in exercise of its power under Article 226 of the Constitution of India, not

only has the power, but even owes a duty to direct further investigation

and/or reinvestigation, as the case may be.

28. The question, which, now, arises for consideration is: Whether in the

case at hand, the direction for further investigation ought to be given by this

Court?

29. Because of the fact that further investigation has been sought for by

the petitioner on the ground of unfairness in investigation, the questions,

which have emerged for consideration are: (i) What is an unfair

investigation ? and (ii) Whether an unfair investigation can be a ground for

directing further investigation ?

30. While considering the above question, one needs to note that the

Division Bench, in Rana Sinhas case (supra), commenting upon the

importance of fair investigation, observed that Article 21 guarantees fair trial

and a fair trial is impossible if there is no fair investigation. In order to be a

fair investigation, the investigation must be conducted thoroughly, without

bias or prejudice, without any ulterior motive and every fact, surfacing

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 24

during the course of investigation, which may have a bearing on the

outcome of the investigation and, eventually, on the trial, must be

recorded contemporaneously by the Investigating Officer at the time of

investigation and, hence, a manipulated investigation or an investigation,

which is motivated, cannot lead to a fair trial. The observations made, in

this regard, which appear at paragraph 1 and 2 of Rana Sinhas case

(supra), read as under:

1. Article 21 guarantees fair trial. A fair trial is impossible if there

is no fair investigation. In order to be a fair investigation, the investigation

must be conducted thoroughly, without bias or prejudice, without any

ulterior motive and every fact, surfacing during the course of investigation,

which may have a bearing on the outcome of the investigation and,

eventually, on the trial, must be recorded contemporaneously by the

Investigating Officer at the time of investigation. A manipulated

investigation or an investigation, which is motivated, cannot lead to a fair

trial. Necessary, therefore, it is that the Courts are vigilant, for, it is as

much the duty of the Court commencing from the level of the Judicial

Magistrate to ensure that an investigation conducted is proper and fair as

it is the duty of the Investigating Officer to ensure that an investigation

conducted is proper and fair. A fair investigation would include a complete

investigation. A complete investigation would mean an investigation,

which looks into all aspects of an accusation, be it in favour of the accused

or against him.

2. Article 21, undoubtedly, vests in every accused the right to

demand a fair trial. This right, which is fundamental in nature, casts a

corresponding duty, on the part of the State, to ensure a fair trial. If the

State is to ensure a fair trial, it must ensure a fair investigation. Logically

extended, this would mean that every victim of offence has the right to

demand a fair trial meaning thereby that he or she has the right to demand

that the State discharges its Constitutional obligation to conduct a fair

investigation so that the investigation culminates into fair trial. The State

has, therefore, the duty to ensure that every investigation, conducted by its

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 25

chosen agency, is not motivated, reckless and that the Investigating Officer

acts in due obedience to law. It is only when the State ensures that the

investigation is fair, can it (the State) be able to say, when questioned, that

the trial conducted was a fair trial. Article 21, therefore, does not vest in

only an accused the right to demand fair trial, but it also vests an equally

important right, fundamental in nature, in the victim, to demand a fair

trial. Article 21 does not, thus, confer fundamental right on the accused

alone, but it also confers, on the victim of an offence, the right, fundamental

in nature, to demand fair trial.

31. It needs to be borne in mind that the allegation against the accused is

that he, being a clerk, committed the offence of criminal breach of trust by

siphoning of the companys fund by showing bogus transactions. It would,

therefore, be not out of place to mention here the basic ingredients of

criminal breach of trust as defined under Section 405 IPC. Section 405 IPC

reads:

Whoever, being in any manner entrusted with property, or with any

dominion over property, dishonestly misappropriates or converts to his own

use that property, or dishonestly uses or disposes of that property in

violation of any direction of law prescribing the mode in which such trust is

to be discharged, or of any legal contract, express or implied, which he has

made touching the discharge of such trust, or willfully suffers any other

person so to do, commits "criminal breach of trust".

32. The prosecution, in a case under criminal breach of trust, is required to

prove the following to bring home the charge of criminal breach of trust.

(i) That the accused was entrusted with property or with any dominion

over property

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 26

(ii) That the accused violated the direction of law prescribing the mode

in which such trust is to be discharged, or of any legal contract, express or

implied, which he has made touching the discharge of such trust.

(iii) That the accused did the aforesaid acts driven by dishonest

intention.

33. It is equally important that the facts relevant to the facts in issue be

proved by person having direct knowledge of the events; hence,

examination of those witnesses, if available, who could give direct

evidence on the ingredients of the offence becomes indispensable part of

investigation.

34. A police investigation must, therefore, take care to investigate the

basic ingredients of the offence of criminal breach of trust not to ensure the

conviction of accused, but to unearth the truth.

35. From the facts narrated by the informant-petitioner and the

grievances expressed on his behalf, it becomes clear that the offence,

alleged to have been committed by the accused, is that he has manipulated

the Cash Book and thereby siphoned off huge amount of money of the

informant company. In this regard, the basic grievance of the informant-

petitioner is that the accused was entrusted with the duty of preparing and

maintaining cash book. What the accused did was that he maintained one

cash book in the computer system and another cash book in the physical

form. In both these cash books, though the days total of cash remained the

same, but in the cash book, which has been maintained in the computer,

the accused allegedly entered various amounts, on the basis of fraudulent

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 27

vouchers, but, in the physical cash book, the entries, as regard fraudulent

vouchers, were absent. It is in this manner that the accused had allegedly

siphoned off, by using fraudulent and fictitious vouchers, money

belonging to the company.

36. In the circumstances, mentioned above, the informant submits, and I

find considerable force in the submission, that it was incumbent, on the

part of the investigating agency, to seize both the cash books, i.e. the cash

book maintained in the computer and the cash book maintained in the

physical form, because it would be well-neigh impossible to prove offence,

if any, committed by the accused without comparing the two cash books,

which he allegedly used to maintain. The said manipulation, it is alleged,

were unearthed by the auditors of the petitioner company, namely, one

Tejesh Kumar Bhattacharjee, whose evidence, as a witness, would,

undoubtedly, be of paramount importance.

37. Similarly, the informant-petitioner also has considerable force in his

grievance that the evidence of the Managers of the periods concerned,

namely, Dipen Bordoloi and Ramanuj Das Gupta, who had signed the

printed version of the cash book, would not only be relevant and

important, but indispensible for effective investigation and fair trial if the

prosecution has to prove its case against the accused. For no reason, either

assigned or discernible from record, the physical cash book was not seized

by the investigating authority knowing fully well that without comparing

the cash books, as indicated above, it is impossible to prove the allegations,

which have been made against the accused. Seen thus, it is clear that

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 28

Tejesh Kumar Bhattacharjee, Dipen Bordoloi and Ramanuj Das Gupta are

vital witnesses and ought to have been cited, in the charge-sheet as

witnesses for prosecution. Amazingly enough, the investigating authority,

during the course of investigation, did not even examine these witnesses or

ask for their attendance.

38. From what have been indicated above, it becomes clear that the

charge-sheet has been filed either on perfunctory investigation or by

deliberately manipulating the investigation. In either case, the investigation,

being inherently defective and lacking in all requisites, would not end in a

fair trial. This would, therefore, cause, unless suitably interfered with,

serious miscarriage of justice.

39. While considering the above aspect of the case, one cannot ignore

the fact that the accused had been an absconder throughout the period of

investigation commencing from 25-06-2008 till 29-10-2009 and was never

arrested and despite the fact that four anticipatory bail applications, made

by the accused, had been dismissed and, in the last application for pre-

arrest bail, he was directed to surrender in the learned Court below, he did

not carry out the order and yet he was allowed to go on bail. This gives an

indication that the investigating officer was either helping the accused or

has conducted the investigation in a manner, which would have the effect

of helping the accused to the prejudice of the informant, which is unfair

and cannot, therefore, be sustained. The investigation is, thus, unfair and

cannot give rise to a valid charge-sheet. Such an investigation, Mr. Baruah is

correct, would, ultimately, prove to be precursor of miscarriage of justice.

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 29

There is, therefore, no doubt that the present one is a fit case for directing

further investigation so that the miscarriage of justice can be prevented.

40. Can the power, conferred on a Court, under Section 311 read with

Section 319 CrPC, be effective substitute for a direction to the Investigating

Agency to conduct further investigation in terms of the provisions of Section

173(8) CrPC ?

41. Coming to the question, which the learned Court below has raised

that it has the power under Sections 311 and 319 to examine any witness

and call for any document and the same would be sufficient substitute for

further investigation, it needs to be noted that Section 2(h) of the Code of

Criminal Procedure ( in short, the Code) defines the term investigation to

include all proceedings under for collection of evidence conducted by a

police officer or by any person (other than a Magistrate), who is authorized

by a Magistrate in that behalf. The Supreme Court, in the case of H.N.

Rishbud Vs. State of Delhi (AIR 1955 SC 196), concluded that investigation

consists of (i) proceeding to the spot (ii) ascertainment of the fact and the

circumstances of the case (iii) discovery and arrest of suspected offenders,

collection of evidence relating to commission of the offence, which may

consist of (a) examination of various persons and the reduction of the

statement into writing, if the officer thinks fit (b) the search of a place or

seizure of the things considered necessary for the investigation and to be

produced at the trial and (iv) formation of the opinion as to whether by the

materials collected there is a case to place the accused before the

Magistrate.

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 30

42. If the very concept of investigation includes the above, as enunciated

by the Supreme Court, then, in that case, can the above be substituted by

taking recourse to Section 311 and 319 of the Code is the question before

this Court. The answer to the question, which has so arisen, can be found

in this Courts decision, in Rana Sinha (Supra), at paragraphs 194, 195 and

196 as under:

194. Before proceeding further, it needs to be noted that section 311 of the

Code, cannot be a substitute for investigation or further investigation

inasmuch as investigation does not consist of only examination of

persons acquainted with the facts of a given case either as witnesses or as

accused; rather, investigation involves various other steps, such as, search

and seizure. Investigation may also include various forensic

examinations.

195. Merely on the ground, therefore, that section 311 empowers the court

to examine any witness at any stage in order to enable it to arrive at a just

decision of the case, it cannot be said that section 311 would serve the

purpose of an effective, unbiased and fair investigation. In every case,

Section 311 is not necessarily a remedy for a manipulated and motivated

investigation.

196. Similarly, Section 319 merely empowers the court to add a person as

an accused if the evidence on record reveals involvement of such a person as

an accused. Section 319 too cannot become a substitute for an effective

investigation so as to determine whether a person is or is not involved in

an occurrence and whether he is required to be brought to face trial. Thus,

neither section 311 nor section 319 can be treated as a complete substitute

for a fair investigation.

(Emphasis is added)

43. Yet another question, which has been raised in the present

application, made under Section 482 Cr.PC., is: Whether in a case, which is

pending in the Court of a Magistrate, it is possible for the Magistrate to grant

permission to a counsel/lawyer engaged by the informant/de facto

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 31

complainant to conduct prosecution or allow the private lawyer to assist the

Public Prosecutor ?

44. The above question has arisen, because of the fact that the learned

trial Court has rejected the request made by the learned counsel for the

informant to assist the Public Prosecutor and the reason, assigned by the

learned trial Court, in this regard, is that in a session triable case, it is the

duty of the Public Prosecutor and Additional Public Prosecutor to conduct

the case. For this, the learned trial Court has drawn support from the

decision in Shiv Kumar Vs. Hukum Chand and another, reported in (1999) 7

SCC 467.

45. While considering the decision, in Shiv Kumar (supra), I may pause

here to point out that under the scheme of the Code, a sessions trial is

required to be conducted by a Public Prosecutor and not by a counsel

engaged by the aggrieved party. However, the police has submitted

charge-sheet against the accused under Section 409 IPC, which is not

exclusively triable by a Court of Session; rather, an offence, under Section

409 IPC, is triable by a Magistrate of first class.

46. In Shiv Kumar vs. Hukam Chand and Anr. , reported in (1999) 7 SCC

467, the appellant, who carried the matter to the Supreme Court, was

aggrieved, because the counsel, engaged by him, was not allowed by the

High Court to conduct prosecution despite having obtained a consent, in

this regard, from the Public Prosecutor concerned. In fact, in Shiv Kumar

(supra), the Court had allowed the prosecution to be conducted by the

complainants counsel. The accused, however, was not prepared to have

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 32

his case prosecuted by the complainants counsel. The accused, therefore,

filed a revision in the High Court. The High Court allowed the revision

and directed the lawyer, appointed by the complainant/private person, to

act under the direction of the Public Prosecutor making it clear that the

lawyer for the complainant/private party may, with the permission of the

Court, submit written argument, when the evidence is closed. The High

Court further specifically directed the Public Prosecutor, who was in

charge of the case, to conduct the prosecution.

47. By the time the aggrieved party challenged the High Courts order,

disallowing the aggrieved partys counsel to conduct the prosecution, the

trial was already over. Considering, however, the importance of the issue

involved, in Shiv Kumar (supra), the Supreme Court decided the issue of

law, namely, whether a counsel, engaged by a complainant/aggrieved

party, can conduct prosecution, in a sessions trial, if the Public Prosecutor

consents thereto ?

48. Having taken note of the provisions of Section 301 and Section 302

of the Code, the Court pointed out that the scheme of the Code is that

while it is the Public Prosecutor of Assistant Public Prosecutor in charge of

a case, who must, according to Section 301(1), conduct the prosecution,

sub-Section (2) of Section 302 permits any private person to instruct a

pleader to prosecute, but the trial has to be still conducted by the Public

Prosecutor or Assistant Public Prosecutor, as the case may be, and the

pleader, so instructed by the private party, shall act under the Public

Prosecutor or Assistant Public Prosecutor, as the case may be. The

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 33

Supreme Court, therefore, pointed out that the latter provisions, contained

in Section 302 IPC, allowing any person to conduct prosecution, is meant

for Magisterial courts and the Magistrate may, therefore, permit any

person to conduct prosecution, the only rider being that the Magistrate

cannot give such permission to a police officer below the rank of Inspector;

but the person, who conducts prosecution in a Magisterial Court, need not

necessarily be a Public Prosecutor. However, such a laxity is not extended

to a Court of Session inasmuch as Section 225 of the Code states that in any

trial, before a Court of Session, the prosecution shall be conducted by a

Public Prosecutor. The Code permits Public Prosecutor to plead, in the

court, without any written authority provided he is in charge of the case;

but any counsel, engaged by an aggrieved party, has to act under the

direction of the Public Prosecutor in charge of the case.

49. In no uncertain words, the Supreme Court made it clear, in Shiv

Kumar (supra), thus: From the scheme of the Code the legislative intention is

manifestly clear that prosecution in a sessions court cannot be conducted by any

one other than the Public Prosecutor. The legislature reminds the State that the

policy must strictly conform to fairness in the trial of an accused in a sessions

court. A Public Prosecutor is not expected to show a thirst to reach the case in the

conviction of the accused somehow or the other irrespective of the true facts

involved in the case. The expected attitude of the Public Prosecutor while

conducting prosecution must be couched in fairness not only to the court and to

the investigating agencies but to the accused as well. If an accused is entitled to

any legitimate benefit during trial the Public Prosecutor should not

scuttle/conceal it. On the contrary, it is the duty of the Public Prosecutor to winch

it to the fore and make it available to the accused. Even if the defence counsel

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 34

overlooked it, Public Prosecutor has the added responsibility to bring it to the

notice of the court if it comes to his knowledge. A private counsel, if allowed free

hand to conduct prosecution would focus on bringing the case to conviction even

if it is not a fit case to be so convicted. That is the reason why Parliament

applied a bridle on him and subjected his role strictly to the instructions given

by the Public Prosecutor. (Emphasis is added)

50. The Supreme Court further clarified, It is not merely an overall

supervision which the Public Prosecutor is expected to perform in such cases

when a privately engaged counsel is permitted to act on his behalf . The role

which a private counsel in such a situation can play is, perhaps, comparable with

that of a junior advocate conducting the case of his senior in a court. The private

counsel is to act on behalf of the Public Prosecutor albeit the fact he is engaged in

the case by a private party. If the role of the Public Prosecutor is allowed to shrink

to a mere supervisory role the trial would become a combat between the private

party and the accused which would render the legislative mandate in Section 225

of the Code a dead letter.

An early decision of a Full Bench of the Allahabad High Court in Queen-

Empress v. Durga (ILR 1894 Allahabad 84) has pinpointed the role of a Public

Prosecutor as follows: It is the duty of a Public Prosecutor to conduct the case for

the Crown fairly. His object should be, not to obtain an unrighteous conviction,

but, as representing the Crown, to see that justice is vindicated: and, in exercising

his discretion as to the witnesses whom he should or should not call, he should

bear that in mind. In our opinion, a Public Prosecutor should not refuse to call or

put into the witness-box for cross-examination a truthful witness returned in the

calendar as a witness for the Crown, merely because the evidence of such witness

might in some respects be favourable to the defence. If a Public Prosecutor is of

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 35

opinion that a witness is a false witness or is likely to give false testimony if put

into the witness-box, he is not bound, in our opinion, to call that witness or to

tender him for cross- examination. (Emphasis is added)

51. A conjoint reading of Section 301 and 302 of the Code would show

that the scheme of the Code is that while it is the Public Prosecutor in

charge of the case, who must conduct the prosecution, in a session triable

case, Section 302(2) of the Code permits prosecution to be conducted by

any person. It has, therefore, been held, in Shiv Kumar (supra), that Section

302 is intended for Magisterial Courts only and this Section, i.e., Section

302, enables the Magistrate to permit any person to conduct prosecution

subject to the condition that the Magistrate cannot give such permission to

a police officer below the rank of Inspector. The Supreme Court has also

clarified, in Shiv Kumar (supra), that in the Magistrates Court, anyone,

except a police officer below the rank of Inspector, can conduct

prosecution provided that the Magistrate permits him to do so and, once

permission is granted, the person concerned can appoint any counsel to

conduct prosecution, in his behalf, in the Magistrates Court. This scheme

of Section 302 is different from Section 301 inasmuch as Section 301 is

applicable to all Courts of criminal jurisdiction and this can be discerned

from the fact that the word employed, in Section 301, is any court. Section

301(1) empowers the Public Prosecutor to plead, in the Court, without any

written authority provided that he is in charge of the case. Section 301(2)

imposes a curb on a counsels engagement by any private party, because

Section 301(2) limits the role of the counsel by allowing him to act under

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 36

the direction of the Public Prosecutor with, of course, the liberty to submit

written argument if the Court permits him to do so.

52. With respect to Section 302, which applies to the Magistrates courts,

any person, except a police officer below the rank of Inspector, can conduct

prosecution provided that permission is granted by the Court. The

observations of the learned trial Court, in the present case, that consent has

to be taken from the Public Prosecutor or from the Additional Public

Prosecutor, is completely foreign to the scheme of the Code. Para 7 to 14 of

the decision, in Shiv Kumar (supra), may be referred to in this regard,

which read:

7. Section 302 of the Code has also some significance in this context and

hence that is also extracted below:

302. Permission to conduct prosecution.(1) Any

Magistrate enquiring into or trying a case may permit the

prosecution to be conducted by any person other than a police

officer below the rank of Inspector; but no person, other than

the Advocate-General or Government Advocate or a Public

Prosecutor or Assistant Public Prosecutor, shall be entitled to

do so without such permission:

Provided that no police officer shall be permitted to

conduct the prosecution if he has taken part in the

investigation into the offence with respect to which the

accused is being prosecuted.

(2) Any person conducting the prosecution may do so

personally or by a pleader.

8. It must be noted that the latter provision is intended only

for Magistrate Courts. It enables the Magistrate to permit any

person to conduct the prosecution. The only rider is that

Magistrate cannot give such permission to a police officer

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 37

below the rank of Inspector. Such person need not necessarily

be a Public Prosecutor.

9. In the Magistrate's Court anybody (except a police officer

below the rank of Inspector) can conduct prosecution, if the

Magistrate permits him to do so. Once the permission is

granted the person concerned can appoint any counsel to

conduct the prosecution on his behalf in the Magistrate's

Court.

10. But the above laxity is not extended to other courts. A

reference to Section 225 of the Code is necessary in this

context. It reads thus:

225. Trial to be conducted by Public Prosecutor.In

every trial before a Court of Session, the prosecution shall

be conducted by a Public Prosecutor.

11. The old Criminal Procedure Code (1898) contained an

identical provision in Section 270 thereof. A Public

Prosecutor means any person appointed under Section 24,

and includes any person acting under the directions of a

Public Prosecutor [vide Section 2(u) of the Code].

12. In the backdrop of the above provisions we have to

understand the purport of Section 301 of the Code. Unlike its

succeeding provision in the Code, the application of which is

confined to Magistrate Courts, this particular section is

applicable to all the courts of criminal jurisdiction. This

distinction can be discerned from employment of the words

any court in Section 301. In view of the provision made in

the succeeding section as for Magistrate Courts the insistence

contained in Section 301(2) must be understood as applicable

to all other courts without any exception. The first sub-section

empowers the Public Prosecutor to plead in the court without

any written authority, provided he is in charge of the case.

The second sub-section, which is sought to be invoked by the

appellant, imposes the curb on a counsel engaged by any

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 38

private party. It limits his role to act in the court during such

prosecution under the directions of the Public Prosecutor.

The only other liberty which he can possibly exercise is to

submit written arguments after the closure of evidence in the

trial, but that too can be done only if the court permits him to

do so.

13. From the scheme of the Code the legislative intention is

manifestly clear that prosecution in a Sessions Court cannot

be conducted by anyone other than the Public Prosecutor. The

legislature reminds the State that the policy must strictly

conform to fairness in the trial of an accused in a Sessions

Court. A Public Prosecutor is not expected to show a thirst to

reach the case in the conviction of the accused somehow or the

other irrespective of the true facts involved in the case. The

expected attitude of the Public Prosecutor while conducting

prosecution must be couched in fairness not only to the court

and to the investigating agencies but to the accused as well. If

an accused is entitled to any legitimate benefit during trial the

Public Prosecutor should not scuttle/conceal it. On the

contrary, it is the duty of the Public Prosecutor to winch it to

the fore and make it available to the accused. Even if the

defence counsel overlooked it, the Public Prosecutor has the

added responsibility to bring it to the notice of the court if it

comes to his knowledge. A private counsel, if allowed a free

hand to conduct prosecution would focus on bringing the case

to conviction even if it is not a fit case to be so convicted. That

is the reason why Parliament applied a bridle on him and

subjected his role strictly to the instructions given by the

Public Prosecutor.

14. It is not merely an overall supervision which the Public

Prosecutor is expected to perform in such cases when a

privately engaged counsel is permitted to act on his behalf.

The role which a private counsel in such a situation can play

is, perhaps, comparable with that of a junior advocate

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 39

conducting the case of his senior in a court. The private

counsel is to act on behalf of the Public Prosecutor albeit the

fact that he is engaged in the case by a private party. If the

role of the Public Prosecutor is allowed to shrink to a mere

supervisory role the trial would become a combat between the

private party and the accused which would render the

legislative mandate in Section 225 of the Code a dead letter.

53. While considering the above aspect of the law, one may also take

note of the Supreme Courts decision in J.K. International Vs. State

(Government of NCP of Delhi) and others, reported in (2001) 3 SCC 462,

wherein the Court has held that a private person, who is permitted to

conduct prosecution in a Magistrates Court, can engage a counsel to do

the needful, in the Court, on his behalf. The Supreme Court has also

clarified, in J.K. International (supra), that if a private person is aggrieved

by the offence committed against him or against anyone in whom he is

interested, he can apply to the Magistrate for permission to conduct

prosecution by himself and it is open to the Court to consider his request

and, if the Court takes the view that cause of justice would be served better

by granting such permission, the Court would, generally, grant such a

permission. The Supreme Court has further clarified, in J.K. International

(supra), that this wider amplitude of power, conferred on the Magistrate, is

limited to Magistrates court only, because such persons right, in

conducting the prosecution, in a Sessions Court, is restricted and is made

subject to the control of the Public Prosecutor. The relevant observations,

appearing, in this regard, at para 12 in J.K. International (supra), read as

under:

Crl. Pet. No. 17 of 2010

Page 40

12. The private person who is permitted to conduct

prosecution in the Magistrate's Court can engage a counsel

to do the needful in the court in his behalf. It further amplifies

the position that if a private person is aggrieved by the offence

committed against him or against anyone in whom he is

interested he can approach the Magistrate and seek

permission to conduct the prosecution by himself. It is open to

the court to consider his request. If the court thinks that the

cause of justice would be served better by granting such

permission the court would generally grant such permission.

Of course, this wider amplitude is limited to Magistrates'

Courts, as the right of such private individual to participate

in the conduct of prosecution in the Sessions Court is very

much restricted and is made subject to the control of the

Public Prosecutor. The limited role which a private person

can be permitted to play for prosecution in the Sessions Court

has been adverted to above. All these would show that an

aggrieved private person is not altogether to be eclipsed from

the scenario when the criminal court takes cognizance of the

offences based on the report submitted by the police. The

reality cannot be overlooked that the genesis in almost all

such cases is the grievance of one or more individual that they

were wronged by the accused by committing offences against

them.