Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A Game-Theoretic Analysis

Transféré par

henfaCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Game-Theoretic Analysis

Transféré par

henfaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Reputation and Hegemonic Stability: A Game-Theoretic Analysis

Author(s): James E. Alt, Randall L. Calvert and Brian D. Humes

Source: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 82, No. 2 (Jun., 1988), pp. 445-466

Published by: American Political Science Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1957395 .

Accessed: 16/09/2013 04:08

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The American Political Science Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REPUTATIONAND

HEGEMONIC STABILITY:

A GAME-THEORETIC

ANALYSIS

JAMES E. ALT

HarvardUniversity

RANDALL L. CALVERT

ofRochester

University

BRIAN D. HUMES

MichiganStateUniversity

We developand explicatea game-theoretic modelin which

repeatedplay,incompleteinformation, andreputation

aremajorelements. A significant

advanceofthismodelis thewayitrepresents underincomplete

cooperation information

amongrationalactorsofdifferentsizes.Themodelis usedtoformalizecertain aspectsof

the"theory of hegemonic It showsthatthe"dilemma"or "limits"

stability." of hege-

monicstabilitylooklikenaturalattributesofgameswherereputationis involved,unify-

ingboth"benevolent" and "coercive"strandsofhegemony An example,drawn

theory.

fromrecent developmentsintheOrganization ofPetroleum-exporting

Countries, shows

how our modelof reputation guidesthestudyof hegemonic regimeconstruction. We

concludeby comparing thenatureof cooperative behaviorunderconditions of com-

pleteand incompleteinformation.

We hereaddress incompleteinformation.Within our

two closelyrelatedpurposes.One is the model,centralfeatures ofthatepisodein-

development andexplicationofthestrate- clude thedifferent productioncapacities

gic nature of "hegemonic"relations of Saudi Arabiaand otheroil producers,

among rationalnation-actors, using a uncertainty about futureworlddemand

game-theoretic modelin whichrepeated foroil, and certaininternalcostsknown

play,incomplete information, and repu- onlyto theSaudis. Our analysisshows

tationare major elements.1 The model thatin hegemonic situations

therecan be

itself has broader applicability. In instability,because reputationalcon-

general,itdescribesa "large"actor'sabil- siderationspredictthat in equilibrium

ityto affectdistributional

outcomesin a actorswill follow"mixedstrategies" of

situationwhere actors compete over challengeand acquiescence,and that

sharesat thesame timethattheycoop- cooperationand information spreading

erateto producea good. willbe severelylimited.

Our otherpurposeis to illustrate

game The significantadvanceofourmodelis

theory as "appliedtheory,"

usedtomodel its abilityto represent cooperativebe-

featuresof situationsand deriveobserv- haviorwhenrationalactorshave asym-

able implications.We considerthe col- metric information anddifferentcapabili-

lapseofoilpricesinlate1985as a gameof ties. Information is asymmetricallydis-

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW

VOL. 82 NO. 2 JUNE 1988

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 82

tributedin thatan actormay knowits amongactorsof information and other

own truecostsand payoffsbetterthan powerresources-lielargely outsideexist-

othersdo. Capabilitiesdiffer to suchan ing game-theoretic analyses of inter-

extentthat,evenifat costto itself,only national regimes.The second section

one "large"actoris able to punish(inflict describesgamesof incomplete informa-

costson) others.Withinthisstructure we tionand showshowreputation addresses

show thatthereexistsan equilibrium of problems ofhegemony. Itthendevelopsa

cooperation undera largeactor'sreputa- modelofreputation, demonstrates thatit

tionfortoughness. Thisdemonstration is producesa Bayesianequilibrium under

important sinceanalystscanviewobserv- mixedstrategies, and describespossible

able behaviorcorresponding to an equi- extensions ofthemodel.The thirdsection

libriumas something reasonablepeople usestheexampleoftherecentcollapseof

coulddo and persistin doing. oil pricesand subsequent behaviorofthe

Thus we bringtogether a numberof nationsintheOrganization ofPetroleum-

previously separate perspectives. Our exporting Countries (OPEC) to elaborate

model accords a major role in inter- on the model. The conclusionprovides

national relations to reputationand further examples, stressesdesirableexten-

threat,as any studentof diplomacy sions, and characterizes differences in

would want. It stressescoercion,but effective strategicchoiceand cooperation

treats regimesas chosen cooperative betweenhegemonicand nonhegemonic

behavior.Mostimportant, itshowswhat situations.

is gainedbytakinga morecomplexmodel

fromtherealmofeconomics andapplying

it to a developing area oftheoryin polit- Hegemonic Stability,

ical science, the (hithertoinformal) Uncertainty, and Reputation

"theoryof hegemonic stability."In fact,

manyof theinsights ofhegemony theory RegimeAnalysis, GameTheory,

turnouttobe features ofa repeated game and Hegemony

ofincomplete information. In formalizing

this theory,our model shows thatthe The interest ingametheory amongstu-

"dilemma" (Stein1984)or "limits" (Snidal dentsof international relationsis closely

1985a) of hegemonic stabilitycan be re- connectedwiththe analysisof regimes.

interpreted as naturalattributes ofgames Regimesareagreed-upon, semivoluntary,

involving reputation. Snidal'sdistinction ongoing, long-run joint maximizing

between "benevolent"and "coercive" strategies thatinduceseemingly selfless

strandsof hegemony theory is thus sub- behavior. Broader than formal agree-

sumedwithina unified model.Thisoffers ments,regimes includeprinciples (stating

hopeofadvancingthepromisethatRug- purposes),norms(generalinjunctions or

gie (1985) ascribesto game theorythat definitions of legitimacy),rules(specific

"both conflictand cooperationcan be rightsand obligations),and procedures

explainedby a singlelogicalapparatus." (formalindications of meansratherthan

Thisaccommodation ofthecentral con- substance).Regimesprescribe actionsfor

cerns of hegemonytheorists(unequal members and persistwhenmembers fol-

resources)and game theorists (strategic low theseprescriptions. Examplesinclude

interaction) proceedsas follows.Thefirst cartels,tradeagreements, financialsys-

section introduces the theory of tems,and thelike.

hegemonic stabilityand showshow cer- Gametheorists havesoughttointerpret

tainfeatures ofthehegemonic situation regimesas cooperativesolutionsto re-

particularlyasymmetricdistributions peatedcollectiveactiongames.Rational

446

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HegemonicStability

actors(thatis,actorswhomaximize long- Significant Featuresof

run net benefitsand choose coursesof HegemonyTheory

actionbasedon theirownpreferences and

expectations of how otherswill behave) Asymmetry ofSize.Thecentral feature of

under appropriatecircumstances have hegemony theoryis thatthehegemonis

sufficient incentivesto cooperatewith "big"relativeto others.Substantively, it

each other.Amongsuch actors,struc- maybe bigin markets, bigin capital,big

tured, regimelikeinteractionswould in resources,or big in militarypower

appearand persist.Whether cooperation (Keohane1984). Theoretically, it has a

ensues in such games dependson the sizeadvantage.Unfortunately, thegame-

structure of payoffs,the probability of theoreticanalysisof regimeshas been

repeatedinteraction, and thenumberof restricted to equal-actor,completeinfor-

players(Oye 1985). mationgames,whichimposesymmetry

Hegemonicstabilitytheoryholdsthat on issues,forinstance, "bytreating a very

spontaneouscooperationin these re- largestateand verysmallones as equal

peated games seldom occurs and that partners in a Prisoners'Dilemma"(Snidal

stableregimesdependinsteadupon the 1985b,47). Our game-theoretic analysis

fosteringactionsofa dominant state.The beginsby assumingthe hegemon'ssize

hegemonic stateprovidesan international advantage,whichwe treatas superiority

orderthatfurthers its own self-interest,in thepossessionof information and in

althoughthe resulting cooperationmay theabilityto inflict costson others.2

workto theadvantageof otherstatesas

well (Snidal1985a, 587). This theoryis Distributional Conflict.Hegemonytheo-

appliedtosuchdiversecasesas Dutch-led ristsrepeatedlyobservethat while all

worldtradein theseventeenth and eigh- hegemonicregimescontaina big actor

teenth centuriesand British trading andmanysmallactors,sometimes thebig

regimes in thenineteenth century by Gil- actorappearsto geta good deal (Snidal's

pin(1981),Keohane(1981,1984),Kindle- "coercive"strand,Kindleberger's "domi-

berger(1973,1981),Krasner(1976),and nance"),at othertimesthesmallonesdo

Stein(1984).A smallpartof theconflict ("benevolent" strandand "leadership").

betweenthe hegemonicstabilitytheory Thisis becausehegemonic stabilitytheo-

and game theoryof regimesreflectsa ries,like otherpoliticaleconomyefforts

debateover theeffects of largenumbers to modeltheroleofenforcement inassist-

on the robustnessof cooperation(Oye ing voluntarycooperationthroughcon-

1985,15). More importantly, hegemony tracting, seek to explainthe sharingof

theorytypically stresses a varietyoffea- anygenerated surplusorgainsfromcoop-

tures-size asymmetries, distributional erating. Such possible "rent-sharing"

conflict,costly coercion,learningand arrangements betweena "big"enforcer (a

uncertainty, and instability-that have "hegemon")and manysmallothers(the

proved difficultto model in game- "allies")forma continuum. One end we

theoreticanalysesof regimes.Although could call an empire,wherethe allies'

someformalization of strategic elements shareis some levelof netbenefitbelow

ofhegemony is desirable, thegametheory whichtheywouldresistor rebel,and the

of international relationscouldprofitby hegemongetstheremainder. The otheris

incorporating important insights ofhege- an alliance,inwhichthealliesgetmostof

monytheorists. Our incomplete informa- thebenefits (say, theprovisionof order)

tionanalysisof hegemony is formulated whilethehegemon mayhardlyfarebetter

to reflecttheseinsights, whichwe now thanwithno regimeat all.

elaborate. In betweenare the most interesting

447

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 82

situations,in whichthegainsfromcoop- One wayis fora weakerhegemon topre-

erationare shared.Here, the hegemon tendto be stronger by "investingin repu-

would alwayspreferto extracta larger tation":bearingsomeinitialcosttoestab-

contribution (net of any cost of extrac- lish a reputationfor"toughness" which

tion)fromtheallies,who(foranylevelof subsequently (ifbelieved)allowscheaper

privatebenefit securedby theavailability coercion.Indeed,thisreputation seeking

of order)in turnwouldalwaysprefer to appearsto be a commonfeature ofhege-

contribute less fortheorderitself.How mony,whether in militarymatters, tariff

good a deal eachgetsdetermines whether wars(Stein1984,371),orfinance(Lipson

theoutcomemorecloselyresembles em- 1985).Naturally, misrepresenta-

strategic

pireor alliance.The keyis thehegemon's tioncan backfire whenbluffsare called

abilitytoforcesubordinate statestomake and futurecredibility requirescarrying

contributions, whichis based on its size out costlythreats(Downs, Rocke,and

advantage.Indeed,as Snidal(1985a,588- Siverson1985, 133; Ward 1987). Our

90) pointsout, if the allies receivenet model formulates more preciselysome

benefits,"theymayrecognize hegemonic reputation-seekingstrategiesand thecon-

leadershipas legitimateand so reinforce ditionsunderwhichtheyare rational.

itsperformance and position."

HegemonicDecline. Finally,a regular

CoercionandCosts.Thehegemon's being feature ofhegemonic regimes is theirpro-

recognizedas legitimate is one way to pensityto decline,a degreeof instability

reducethecostofextracting contributions remarkable in something theorized about

fromtheallies.Thishighlights theimpor- foritsstability. Buttheredoesn'tseemto

tantrole of the cost of coercionin the be muchdoubtaboutwhytheydecline.

theoryof hegemony.3 The cost of coer- Oye (1985,5) citesa studyby McKeown

ciondependsonwhatis donetocoerce.In thatshowshowunanticipated downturns

trade,if the hegemonentersan ally's in thebusinesscyclealterthebenefits of

marketscompetitively, it may have to opentradepolicies,and Stein(1984,349)

bear the cost of subsidizingits own attributes instabilityto differentialrates

exports.In defense,withdrawal of mili- ofeconomicgrowth andrapidlychanging

taryprotectionforcesthe hegemonto markets. Buta hegemonic regime founded

bear the costs of findingalternatesites on reputation containsitsown sourceof

and arrangements forrefueling, sincereputation

training, instability, requiressome

and stagingof exercises.Effective sub- uncertainty about futurecosts of coer-

maynotbe available.Our model cion. Repeatedinteractionmay allow

stitutes

bringsout clearlytheway in whichthe alliesto learnmoreaboutthehegemon's

costof punishing is thekeyto thehege- nature,erodingthereputational basis of

mon'sstrength. We distinguish between an existingregime.Of course,costs in

"strong"hegemons,who coerceat low turnmayalso changewithunanticipated

cost,and "weak"hegemons, who coerce changesin a widerworld(of trade,or

at high cost but mightin appropriate whatever) beyondthecontrolofthehege-

situationsnevertheless fromcoer- monorregime,

benefit producing theappearance

cion. Bothsortsare distinct fromallies, of instability.

who are assumedincapableof coercing

profitably. Summary.We identifya regimewith

equilibriumbehavior in which actors

Reputationand Uncertainty. But how maintaincooperation.Cooperationneed

doesa hegemon gettobe "legitimate" and not entailhegemony, and thusKeohane

thuscollectcontributions withoutactual- (1984) can be rightin claimingthat

ly carrying out costlycoerciveactions? hegemonic stabilitydoes notexplainthe

448

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HegemonicStability

Bretton Woods regime.Snidal(1985a)is of modelingassumptions used in more

also rightto say thatdeclining

hegemony traditionalgame-theoretic approaches.In

maybe replacedby eithercooperation or gamesof incomplete and asymmetric in-

conflict.A formalmodel of hegemony formation, theplayersdo not knowthe

shouldaddressthisaspectoftheproblem entire structureof payoffs. Indeed,

and also have roomforcostlycoercion, playershavedifferent information. Each,

learning,uncertainty, and decline.We forexample,mayknowonlyitsownpay-

believethatstrategic reputationbuilding offs. With repeatedinteraction, these

is thekeyto modelsofhegemonic stabil- information conditionsareprecisely what

ity.We shallseebelow(1) howthetheory createthe possibilityof reputation, as

of gamesof incomplete informationcan well as learningand adjustment (Snidal

addressall thesepoints;(2) how asym- 1985b;Wagner1983).

metricinformation coupledwithcostly Consider,for example,the "empire"

coercionprovidespossibleincentives to pole of the continuumof hegemonic

investin a reputation fortoughness;and arrangements. Here,a coercivehegemon

(3) how reputation in turncan-produce exploitsalliedstatesby forcing behavior

regimesthatlook moreor less like em- costlytothemandallowingthemminimal

piresor alliancesbutthatcontainwithin benefitsin return.Coercion,involving

themtheseedsoftheirownunraveling. militaryforceoreconomic sanctions, may

be costlyto the hegemonas well. The

coststo thehegemonwillvaryfromone

The Game Theoryof situationto another,andmaynotbe pre-

Reputationand Leadership ciselyknown to the vassal states.As

a result,the hegemoncan sometimes

Gamesof Incomplete

Information threatenpunishments whosetruecosts,if

carriedout,wouldoutweigh theexpected

Our modelis a repeated gameofasym- benefits fromthecoercedbehavior.Ifthe

metric incompleteinformation.Most allies'uncertainty meansthatthethreats

game-theoretic applicationsin interna- do notalwayshaveto be carriedout,the

tionalrelations(and in politicalscience resultsmay profitthe hegemon,which

generally) haveemployed gamesofcom- buildsa reputation forbeingmoreableto

pleteinformation; thatis, thestrategies punishthanit actuallyis.

availableto all playersand theresulting At theoppositepole,thatof"alliance"

payoffs forall playersare assumedto be hegemony, reputation is equallyimpor-

commonknowledge.Phenomenaincom- tant. Suppose firstthatseveralnations

patiblewiththeseassumptions, such as wouldbe nearlyequal beneficiaries from

commitment, bluffing, and reputation, providing a collectivegood but thatone

are usuallydescribedas "situational fea- of them(thehegemon)is able to provide

tures"not analyzablewithinthe game- selectiveincentives,perhapsthrough mili-

theoreticmodel.4Forsubjectslikeregime taryoreconomicactionsunrelated to this

stability,in whichincomplete informa- collectivegood.Theseincentives arecost-

tionand reputation maybe central,such lytothehegemon; and,again,thecoststo

analysesbecomeinformal justat thepoint thehegemonvaryand are not perfectly

wheregame-theoretic rigorshould,ideal- knownto thehegemon's allies.The allies

ly, play its most importantrole: the knowtheirnetbenefits fromboththecol-

analysisofcomplexstrategic interaction. lectiveandselective goodsandknowthat

Game theorists, beginning withHar- thehegemonhas an incentive to mislead

sanyi (1967-68),have devisedtools to themby misrepresenting its costs.They

bringthesephenomena underthesameset are tempted to challengetheregime, that

449

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 82

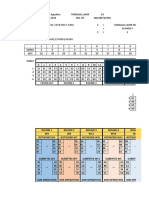

Figure1. The HegemonyGame A Gameof Reputation

underIncomplete

Information

Payoffs

Ally

In this sectionwe examinea purely

Ally obeys

0 a game-theoretic approachto theproblem

ofreputation building.The modelallows

Hegmon us to derive the choices, deceptions,

acquiesces guesses,andlearning processes

Ally

b 0 ofrational

challenges playersina settingofincompleteinforma-

tion. It yieldsa sequentialequilibrium,

b-i _xt whichwe exploitto analyzethenatureof

reputationand of rational reputation

Assumptions: 0< b' I

ao I

building.5

x a (I withprobabilityw Assumptions. Our modelassumesthatin

l0 withprobability1-w

each of two periods,a hegemonfacesa

potentialchallenge froma singleally.6In

periodt, allyt can eitherobey(adhereto

thebehaviorrequired intheregimeoralli-

ance) or challenge(go againstthehege-

is, to dump some steel, reduce an ex- mon's wishes).If ally t challenges,the

changerate,reducedefenseexpenditures. hegemoncan eitherpunishthatally or

But the hegemon can gain benefitsfor acquiesce.Ally 2 learnstheoutcomeof

itself (and the allies) by occasionally period1 (obey;challengeand acquiesce;

applying selective incentives, even if or challengeand punish)beforemaking

costly, maskingits true patternof costs itsownchoicesin period2. Figure1 dis-

and counteractingtheir temptationsto playsa singleperiodofthisgameinexten-

challenge. siveform.

In either of these settings,or any in As thefigure shows,an allywhoobeys

between,we have a hegemonthreatening receiveszero. An ally who challenges

otherstateswithpunishmentfornot con- receivesb (O < b < 1). Punishmentexacts

tributing.Uncertaintyabout the cost of a penaltyof one, so an ally who chal-

those punishmentspresentsthe hegemon lengesand is punishedreceivesb - 1.

witha chance to maximizeits benefitsby Thuseach allyprefers mostto challenge

threatening,promising,sometimespun- and not be punished;challenging and

ishingor rewarding,creatinga reputation being punishedis the worst outcome.

for willingnessto punish. The most suc- (The value of b could be assumeddif-

cessful,stable regimesof thissortwill be ferent foreachallywithout changingany

the ones in which the hegemonoptimizes of ourresults.)

its use of thesecostlythreatsto createthe In each periodthehegemonreceivesa

desired reputation.Of course, if a hege- payoff ofa (a > 1) iftheallyobeys,and

mon could almost always punishwithout zeroiftheallychallenges. Ifthehegemon

cost, regimemaintenancewould be easy choosesto punisha challenge, thecostof

and stable hegemony common. The punishmentin period t is Xt, where xt is

assumption underlyingour approach is one (costly)withprobability

w and zero

that hegemonsmust typicallydepend on (cheap) withprobability1 - W.7 The

costlypunishment.Thus by focusingon hegemonlearnsthevalueofxtat thebe-

reputationbuilding,we analyze decision ginningof periodt, beforeeitherplayer

makingat themarginthatis mostrelevant makesa moveinthatperiod,butfacesthe

to regimestability. probleminperiod1 ofchoosinga rational

450

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HegemonicStability

strategyforthatperiodwithoutknowing includes thefollowingelements: (1) a move

whetherpunishment will be costlyin (obeyor challenge)to be madeby ally1

period2. This is a key featureof our that,giventhe hegemon'sstrategy and

approach:unlikeothermodelsin which ally 1's beliefsabout W, maximizes ally

the hegemonis alwaysstrongor weak, I's expected payoff;(2) a ruleforally2 for

here thereis some uncertainty for the responding to the outcomeof the first

hegemonas well. period,whichmaximizes ally2's expected

The valueofw mightbe thought ofas payoffgiventhehegemon's strategy and

the"expected weakness"ofthehegemon. givenally 2's updatedbeliefsabout W,

The higherthevalue of w, the"weaker" usingBayes'ruleto takeintoaccountthe

the hegemon,that is, the more likely outcomeof period1; and (3) a strategy

punishment is to be costly.We assume thatmaximizesexpectedpayoffforthe

thatthehegemon knowsthetruevalueof hegemon,giventheallies'strategies, de-

w-how weakhe or sheis on average- scribing howthehegemon wouldrespond

butnotwhether an individual punishment inperiod1 ifally1 challenged andhowto

episodewill be costlyuntilthatperiod respondifally2 challenges, giventheout-

arrives.Allieshave an initial,subjective comeofperiod1, foreachpossiblevalue

estimateof w summarized by a random of thehegemon's privateinformation (w,

variableW; buttheyneverlearnthehege- x1,andx2).In thisandthenextsectionwe

mon'struecosts.As thegameproceeds, describesuchan equilibrium and discuss

alliescan tryto makeinferences aboutw certainofitsproperties. Formalproofsof

fromobservingthe hegemon'sinterac- theseresults areoutlined intheAppendix.

tions with otherallies; but theyonly In this equilibrium,the hegemon

observe acquiescenceand punishment, alwayspunishesinperiodt (t = 1 or2) if

notwhether punishment was costly. xt = 0 andneverpunishes inperiod2 ifx2

So thattheallies'Bayesianupdatingof = 1. Thelatter is required becausethereis

theirbeliefsaboutw be relatively simple, nothingto be gainedby punishing in the

we assumealso thatW has thebetadis- finalperiod.(Whether thereis eversucha

tribution.Intuitively, theirbeliefsdepend "finalperiod"in therealworldis an issue

on two parameters ae and 13,whereae to which we return subsequently.)

countscostlypunishments and 1 counts Beyond this, each player's behavior

cheap ones; oi/(ai+ ,3) is theally'sex- dependsupon thevalue of b, theallies'

pectedprobability thatthehegemonwill payoff,relativeto the allies' beliefsas

facea costlypunishment.8 In equilibrium, describedby axand ,3.In effect, thisis a

by observingthehegemon'sbehaviorin comparisonbetweenthe temptation to

case ofa challenge inperiod1, ally2 can challengeand the danger(i.e., theesti-

updateW, thatis, modifya and ,3using matedprobability together withtheally's

Bayes'rule,assumingthatthehegemon confidencein that estimate)that the

followsitsequilibrium strategy. hegemon can punishcostlessly.

To illustrate

thereasoning behindthis

Equilibrium. The solutionto sucha game equilibrium, supposefora momentthat

of incompleteinformation is called a therewereonlyone periodof play and

Bayesian(Nash) equilibrium(Harsanyi thattheallybelievedthehegemon would

1967-1968),whichis an internally con- punishifthiswerecheapandnotifcostly.

sistentcombination ofactionsand beliefs Thentheallywoulddecidewhattodo by

such thatneitherplayerwould wish to makingan expectedvalue calculation.It

changeitsactionsunilaterally, giventhe could challengeand getaway withit (if

assumedincompleteness of information. punishment werecostly),receiving b with

A Bayesianequilibrium forourgamethen probability + p3);itcouldchallenge

oa/(oa

451

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 82

Figure2. Temptation,Danger, and the Four Cases of EquilibriumStrategy

Case 1 Case 2 , Case 3 Case 4

I ~ ~ I ~~ 3~Value lo- ofb

I (Temptation)

's _ ra +3 __+1_

a+13+I a+/3 a+/3 a+/3+1

and be punished,receiving (b - 1) with r= {1[-Vbao + 3 + 1)- A1]}

probability f3/(a+ 3); or it couldobey, a[b(ac + 3 + 1) - (]

receivingzero. Summing,the expected

payofffromchallenging is thenb -/(a that is, the hegemonpursuesa mixed

+ A); so theally in such a case would strategy.The allies' behaviordepends

challengewheneverb > f3(ca+ p3). uponwhichofthefollowing twosubcases

Repeatplay opensup the possibility of applies:

reputation and deterrence and so compli- Case 3'. b < (roe+ f3)I(oz+ O). Ally1

catesthecalculation.In fact,theequilib- obeys.Here,ally1 is deterred, notby the

riumcomprises fourseparatecases,illus- highprobability ofa costlesspunishment

tratedin Figure2. butbyappreciation ofthehegemon's will-

Case 1. b < 3(c + a + 1). The allies' ingnessto engagein reputation building.

benefit fromchallenging is so smallrela- However,ally 2, who will onlybe pun-

tiveto theprobability of costlesspunish- ishedif it is costless,alwayschallenges.

mentthattheyneverchallenge.Even if The hegemonhas not had a chanceto

ally 1 did (irrationally) challenge,the builda reputation.

hegemonwould not need to punishin Case 3". b > (rae+ 0)/(ca+ f3).Here,

orderto detera rationalchallengefrom ally 1 challenges.If thehegemonacqui-

ally2. Formally, in equilibrium thehege- esces,thenally2 also challenges. Ifally1

mon neverpunisheswhenxt = 1 and is punished,thenally2 pursuesa mixed

neither allychallenges. strategy, obeyingwithprobability 1/a.In

Case 2. f/(oa+ 3 + 1) < b S f3/(ao + otherwords,thepunishment sometimes

O). Here the temptationis somewhat detersally 2; the lower the hegemon's

greater,but stillally 1 is afraidto chal- incentiveto deter,the more oftenthis

lenge.Withno revisionin initialbeliefs, deterrence is successful.

Ally2 has a sus-

therefore, ally2 also obeys.However,if piciousnature.

ally1 had irrationally challenged and the Case 4. b > (f3 + 1)/(oa + (3 + 1).

hegemon had acquiesced,ally2 wouldbe Symmetrically withcase 1, herethetemp-

willingto challenge.9To deterthis,a tationis so highthatthe allies always

hegemonalways punishesa challenge challenge.Evenif thehegemonpunishes

fromally1, evenifcostly. ally 1, ally 2 cannotbe deterred, so the

Case3: f/(oa+ ) < b < (q + 1)/(x + hegemonnever applies costly punish-

a + 1). This is substantively the most ments.

interesting case, because herethe hege- The strategiesspecifiedconstitutea

monmustactivelyestablish a reputation. Bayesianequilibriumto the hegemony

If x1 = 1, thehegemonpunishesa chal- game.It is also a sequentialequilibrium

lenge fromally 1 with probabilityr, (Krepsand Wilson1982a). Amongother

where things,a sequentialequilibrium is "sub-

452

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HegemonicStability

gameperfect," meaningthatit is rational deterrent effect,thehegemon wouldhave

to carryoutanythreats shouldtheocca- no incentiveto carryit out. Similar

sionariseeveniftheoccasionshouldnot reasoning showsthatthehegemon cannot

arise underequilibriumbehavior.This avoid all costlypunishment and thatally

appliesespecially to theimplicit threatby 2 cannotrespondto first-period punish-

the hegemonin case 2 above to punish mentbyalwaysobeying.In general,such

anychallenge by ally1, although inequi- purestrategies, ifexpected by opponents,

librium ally1 neverchallenges. A sequen- would bringabout strategic adjustments

tial equilibrium is also "trembling-handthatwouldleavethepure-strategy player

perfect," meaningthatitis robustagainst dissatisfied withitsownstrategy. Onlyif

at least some possibility of mistakesby all playersmutually intendto carryout-

theplayersin makingtheirmoves(Selten and expectone anotherto carryout-the

1975). specifiedmixed strategies,will each

playerbe satisfied withbothitsstrategy

MixedStrategies andEquilibrium Reputa- and its expectations about the others'

tion-Building. This equilibrium features strategies.Reputationbuildingthrough

realisticreputation buildingby thehege- mixedstrategies is theonlystable,consis-

monin case 3". In cases1 and2, no chal- tent,rationalcombinationof strategies

lengeshouldevertakeplace;andincase4 and expectations forall players.10

challenges are neverdeterred, so thereis Theoretically, a mixedstrategy is onein

In

neverany punishment. case 3, how- which a player chooses among the avail-

ever, the hegemontakes advantageof able "pure"strategies at random,accord-

opportunities to build a reputationby ing to some predetermined probability

sometimesinvokingcostlypunishments distribution. Theresultofthisrandomiza-

to tryto deterally2 fromchallenging. In tionis notobservedbytheopponent until

turn,ally2 is indeedsometimes deterred. aftertheopponent's (here,ally1's) choice

Most importantly, all this behavioris is made (Luce and Raiffa1957, 69-71).

rationalfortheplayerseventhoughthe Behaviorally, a hegemon canachievesuch

allies are sophisticated about the hege- a mixedstrategyby basing the choice

mon'sincentive to deceive,thehegemon upon some exogenousvariable whose

is awareofthatsophistication, andso on. valueis knowntothehegemon at thetime

Thiscontrasts withreputation buildingin ofchoice(butnotbefore)butonlyknown

modelssuchas thatof Bramsand Hessel probabilistically to the allies. For in-

(1984). stance,inan international gamewe might

A significant featureof thereputation- thinkof thehegemon's truecostof pun-

building behaviorpredicted bythismodel ishment as beingxtplus a randomvalue

is thatit necessarily involvestheuse of v, representing specialdomesticpolitical

mixedstrategies by thehegemonand by considerations learnedby thehegemon at

ally2. To see thatthisis necessary, sup- thetimeof choice,perhapsin a separate

pose insteadthatthehegemon's strategy game involvingthe hegemonbut un-

incase3 werealwaystopunishinequilib- observableby others.If beforehand all

rium,regardless ofcost.Thenobserving a playersexpectthatv is less thansomev'

first-periodpunishment wouldconveyno withprobability r, thenwhenxt = 1 the

new information about the hegemon's hegemonwould punishif v < v' and

strength and ally2 wouldnotupdateits acquiesceotherwise. (Formoredetailsee

beliefsand would challengeeven if the Harsanyi1973.)We elaborateon therole

hegemon had punished.Sincecostlypun- ofsuchuncertain costsofcoercionin the

ishment in period1 wouldthenhave no oil priceexamplediscussedbelow.

453

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPoliticalScienceReview Vol. 82

HegemonicDeclineand OtherResults a hegemonicregimecould declineafter

havingat firstsucceeded.(We assume

In orderto incorporate thehegemon's throughout whatfollowsthatthenations

uncertainty about futurecosts,we were involvedare in a situation corresponding

able todescribetheequilibrium onlyfora to case3".) First,theveryfactofrepeated

two-periodgame. However, thereare play can reducethepossiblescope of a

reasonsto believethatimportant proper- hegemonfor reputationbuilding,even

tiesof our resultswould stillhold in a without allieshavingbeeninitially wrong

gamewithmoreperiods.Suchan exten- in theirestimates ofw. Repetition reduces

sionwilloffer significantinsightsintothe thevarianceofW andincreases theircon-

relationship betweenreputation and the fidence intheirestimates.12 In thissense,a

declineofhegemonic regimes. reputational modelofa hegemonic regime

A Multiperiod Model?Krepsand Wilson contains within it possible sources of the

(1982a)modeledreputation buildingby a regime's ultimate disintegration without

predatory monopolist in a settingsimilar requiringfurtherargumentsabout un-

to ours,allowingforan arbitrary finite anticipated exogenouschange.

numberofrepetitions. Our resultsresem- Moreover, theuse of mixedstrategies

ble theirsclosely,withtwoimportant dif- by the players maybringaboutdecline.In

ferences. First, if the Kreps-Wilson our two-period model,ally 2 maychal-

monopolist everoncefailstopunish,then lenge even though thehegemon punished

thejig is up: all otherplayersknowfor a challenge by ally 1. In a multiperiod

certainthatthemonopolist cannotreally model (or indeed the Kreps-Wilson

affordto punishand (as a result)will model),thesamescenariocouldunfoldat

neverdo so again.In ourmodel,a hege- any time. The hegemonmay punish

monwho failsto punishin period1 may severaltimes,establisha reputation that

yetpunishin period2 ifx2 0. Second,

= deters some challenges, then be (ran-

our model,unliketheirs,exhibitssitua- domly)challenged, and(randomly) failto

tionsin whichthehegemonis so welloff punish, incurring further challenges from

thatit neednotworryaboutreputation, which it may be difficult or impossible to

as wellas circumstances inwhichreputa- recover. As we have seen, equilibrium

tion buildingis hopeless.In otherre- behaviorrequiresmixedstrategies; there-

spects,the Kreps-Wilson resultscorre- fore a rational hegemon must leave itself

spondcloselyto ours." Thesesimilarities open to this kind of hegemonic decline.

indicatethatif our modelcould be ex- Finally,theonsetof thelateperiodsof

tendedto arbitrary finitelength,it ought the gamemaybringaboutthedeclineof

to exhibitbehaviorsimilarto theKreps- theregimethrough thehegemon's loss of

Wilsonmodel.Forinstance, depending on reputation. With no updating, ally 2 hasa

parameter values,thehegemon's reputa- smaller chance of being punished than

tionmayendurefortheentiregame,or does ally 1, simply because only a costless

withtheapproachof thefinalperiodthe punishment willbe metedoutin thefinal

alliesmaybecomebolder.Ifthishappens, period. This makesally2 morewillingto

thehegemon mayresistat first,temporar- challenge, other things equal. Thiswould

ily reestablishingitsreputation. In other be an ongoing process. Challenges

cases, the hegemonmay give up early, become more and more attractive in the

and endurechallenges fortherestof the laterperiods, and under some conditions

game. obediencebreaksdown severalperiods

beforethe last. If therewere anything

HegemonicDecline. These resultsand resembling an "end of thegame"in real

extensions openup severalwaysinwhich life, this would providean additional

454

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HegemonicStability

source of hegemonicdecline, again toughness,that is, an abilityto force

despitethefactthattheregimemayhave downoilpricesandwithstand thecostsof

workedperfectly wellinitially. prolongedperiodsof low pricesin order

Is theresuchan "endof game"?Inter- todeterfuture production byothers, both

nationalpoliticsis perhapsmoreaccurate- withinand outsideOPEC. We also give

ly characterized as an infinite-horizonevidencethattheirexpectedgainsfrom

game.Eventhougha regimemayendfor thisstrategyexceededany likelygains

exogenousreasons,theplayersneedhave fromalternative strategiesthathavebeen

no advance warningof it. Undersuch imputedto them.Finally,the1985price

conditions,theywill behave as though declineis one of a seriesof similarepi-

theyexpectthegameto go on forever but sodes involvingthe Saudis, some suc-

discount futurepayoffs duetouncertainty cessesandsomefailures, someattempts at

(as forexamplein Axelrod1984). If this punishment and someacquiescence, very

discounting is not too severe,thensuch much resemblingthe applicationsof

behaviormaylook verymuchlikeearly- mixedstrategies describedabove. Thus,

periodbehaviorin an incomplete infor- whatlooksfromsomeperspectives likean

mationgamewitha longbutfinitehori- episode of regimebreakdownappears

zon. Withheavierdiscounting, thestrate- insteadto us as thesortof event(chal-

giesresemble last-periodplayina finitely lenge,punish,acquiesce)thatdetermines

repeatedgame.Ifplayersreceivewarning thebasisoffuture regimecooperation in

that the game is likelyto end sooner an ongoing,oft-repeated international

ratherthanlater,the effectis precisely interaction.

thatof increasing therateat whichthey

discount thefuture.13 sucha

Strategically, Background

changein discounting shouldlook a lot

likeapproaching theendofa finite game. The Saudi actionin 1985 followeda

The pointis thathegemonic regimes may period of major changesin patternsof

declineas theyapproach,butbeforethey supply and demandforoil. As Figure3

actuallyreach,theexogenously imposed shows,Saudi productionthenstood at

end oftheline. about 2 millionbarrelsa day (mbd),

downfrom5 mbdjustovera yearearlier

and froma highof about 10 mbd five

An Example: yearsbefore.Indeed,fora briefmoment

The Price of Oil in 1985 Saudi Arabiawas no longerthe

world's largestproducer,thoughtheir

In the late summerof 1985, Saudi provenlow-costreserveswerestilllarg-

Arabiabegansubstantially increasing oil est.As Table1 shows,partofthisdecline

productionfor export,precipitating a intheSaudis'market sharewasa response

largedropin theworldpriceof oil. We to decreasedworlddemand,whichhad

applyourmodeltothisepisodetoanalyze fallenby over10% since1980.It also re-

the strategies pursuedby Saudi Arabia flectedincreasedproductionby non-

and othernationsas a qualitative illustra- OPEC nations (especiallyBritainand

tionof reputation buildingin hegemonic Norway).However,mostof thereduc-

relations.As we shall see, incomplete tion reflected the Saudis' majorrole in

informationand coercion costs play OPEC's effort to decreaseproduction to

majorrolesinthisepisode,inwhichSaudi shoreup thepriceofoil. The quotalevels

Arabiawas inthepositionofa hegemonic negotiated in late 1984 (whichprovided

actor.We giveevidencethattheSaudis' forOPEC production of nearly16 mbd)

goal was to establisha reputationfor broughtSaudi production down to just

455

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 82

Figure3. OPEC Crude Oil Production Sea producers,Britainand Norway.

6 Saudi oil production doubledto

initially

MIllUnB/D over 5 mbd in summer 1986, though fol-

5 lowing furtherOPEC it

negotiations has

~~~~udi

Arabia

4- sincefallencloserto 3 mbd.Therewere

scatteredproductioncutsby othercoun-

3 iron n tries(bothOPEC members and nonmem-

bers but not Britainor, untilrecently,

Norway),and thepriceof oil fellfrom

Iraq Nigeo above$30 tobelow$10perbarrel,recent-

O . I A

I below$20.

ly fluctuating

1984 1985 1986

senior

Note. We are gratefulto J. L. Johnston, Interpretations

economist,AmocoOil Corporation, forsupplying

thisfigure. WhatmighttheSaudis have wanted?

Some (including, apparently, Saudi

propagandists) claimedtheysoughtto

over4 mbd.A yearlaterOPEC was still create structuraleconomicchangesto

producingatnearlythesameoutputlevel, increaseworlddemandforoil. Thiscould

butSaudiproductionhadbeenhalved.By be true,but onlyas a meansto increase

contrast,the combinedproductionof theirown revenues.Othersargue that

Norway and Britain(not membersof theywantto maximize market share(edi-

OPEC) had reached3.5 mbd by 1985, of torial,Wall StreetJournal,30 January

whichhalfwas exported.Theirexports 1986). Increasingmarketshareplays a

hadbeennegligible (lessthan.5 mbd)five roleinouraccount,too,butisnota moti-

yearsbefore. vation independentof price; for the

In December1985,theSaudisachieved Saudis alone can have thewholeworld

a majoritydecisionin OPEC to abandon marketat two dollarsa barrelfor 15

production

their joint price-stabilizing years. Alternately,journalist Henry

quotasandthreaten a pricewarwithnon- Jacoby("A Shock That OPEC Won't

OPEC producers, particularlytheNorth Overcome," New YorkTimes,26 January

1986)interpreted situation

thepresent as a

Table 1. WorldOil Production, dilemma,"withOPEC

"classicprisoners'

1980 and 1985 and non-OPECmembersable to benefit

jointlyfromreducedproduction but un-

Millionsof able to make bindingagreementsto

BarrelsperDay foregoproduction. Thus,he argued,the

SourceofOil 1980 1985 competitive outcomewillbe worseforall

producersthancontinuing OPEC quota

Exports cooperation;and the squabblingover

SaudiArabia 10 3

RestofOPEC 15 11 pricesandproduction theirinabil-

reflects

Non-OPEC 4 8 ityto enforcecooperation.

Totalexports 29 22 We believeinsteadthattheepisoderep-

resentsan effortto maintainan oil pro-

production

Indigenous 21 22 ducers'regimeunderSaudi hegemony.

Totalworlddemand 50 44 Hegemonytheorists wouldarguethatno

Note. We are gratefulto J. L. Johnston,

senior stableoil producers'

regimewas possible

AmocoOil Corporation,

economist, forsupplying unless backed by a "large"power. In

fromwhichthesedatawerecalculated.

figures markettermstheSaudisare certainly the

456

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HegemonicStability

largestoil-producing nation. However, ingsof$60 millionperday.At thislower

theirpositionas swingproducer(accept- production level,theirreserveswouldlast

ingcutsin production to propup prices) longer.Indeed,giventhe scale of their

meantthat OPEC in late 1985 closely reserves, theSaudisshouldprefer suchan

resembled,in our terms,a hegemonic outcometocompetition without quotasat

"alliance."Could Saudi Arabia use its discountratesforfutureearningsbelow

superiorreservepositionto alterthedis- about3% per annum.Thus,theSaudis'

tribution of benefitsand restoreits pre- betterstrategy mightbe to competeby

vious positionwithinOPEC? This de- producing6 mbd,contrary to observed

pendson whether itis willingto bearthe behavior,thoughpossibledataerrors and

short-term costsofverylow oil pricesin uncertainty overdiscountratesmakethis

orderto maximizerevenuesin thelong a tentative conclusion.

run,andwhether othernations(including However,thisignoresthe possibility

thoseinOPEC) areconvinced ofthiswill- thattheSaudiscoulddeterfuture explora-

ingness.Ifso, theSaudi actionis a credi- tion and productionby establishing a

ble threatand detersentryor excesspro- reputationfor toughness,which they

ductionby some othercountriesafter coulddo in eithercase. Theywouldhave

pricesrise.14 to withstand a longenoughperiodoflow

First,the1985 pricefallis not an iso- oil pricestopersuadeothernations(oroil

lated episode. As Ahrari(1986) points companies)to deferexploration and in-

out, the Saudis have acted similarly on vestmentthroughthe threatof future

two previousoccasions,1977 and 1981. punishment (furtherperiodsoflowprices)

On those occasions, he argues, their withoutactuallyhaving repeatedlyto

initiativesfailedbecause marketcondi- carryoutthethreat.It wouldbe worthit

tionsremainedtight.This is consistent to dissuadeenoughexploration and in-

with our overallstresson viewingthe vestment to add evenas littleas 10% to

problemas one of repeatedinteraction, the long-run priceof oil. Withsuch an

andhighlights theimportance ofthehege- improvement, theSaudismight produce6

mon'suncertainty aboutthepriceelastic- mbdat $17 perbarrelundercompetition

ityofworlddemandforoil. or4 mbdat $25underquotas.16Theextra

Equallyimportant, theSaudiscan gain $10 millionper day thus gained from

morefromreputation thanunderother reputation wouldexceedthelikelydiffer-

cooperative outcomes.Forexample,pub- ence (withoutreputation) betweencom-

lishedestimates usingconventional analy- petitionand quotas.

sisofsupplyand demandshowedthatthe

Saudiscouldmaximize theirforeignearn- Costsof Coercion

ingsat about$65 millionperdaybypro-

ducing6 mbd at $15 per barrel,under Withtheirenormous low-costreserves,

conditionsapproximatingcompetition theSaudis'abilitytowithstand periodsof

without quotas(NewYorkTimes,19 Feb- low prices providesthe possibilityof

ruary1986).15Otherjournalists and ana- establishing a reputationfor toughness

lystsof the Wall StreetJournalargued fromwhichtheycan subsequently profit

thatOPEC would eventually reestablish -if theycan bear the costs of driving

quotas and speculatedthat the Saudis pricesdowntogetthatreputation. Before

wouldproduceabout4 mbdat $22 a bar- the fact,the Saudis may have believed

rel. (Above this price,apparently,the theycould affordthisstrategy. Recently

incentivesforcompetitive entryby many announcedaccountsshowthattheSaudis

small producersmultiplyrapidly.)This had a budgetdeficitof $13 billion,or

latterarrangement wouldgivethemearn- about $36 milliona day, whileearning

457

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 82

about$50millionperdayfromoilin1986 Success,Failure,and MixedStrategies

(equaltotheearnings on about4.5 mbdat

$13 a barrel).Two pointsfollowfrom Even with this difficulty, the Saudis

this.First,thisrateofearningsis $10-$15 have done relativelywell so far. The

million per day below the industry August1986 OPEC agreement accorded

analysts'quoted estimatesof what the theman improvedquota. A numberof

Saudis could have made withoutestab- allies, both inside and outsideOPEC,

lishinga reputation.However,such a linedup production cuts.The speedwith

shortfall

sustained for6-12monthscould whichtheyfellintolinereflects thecostof

be madeup by exploiting reputationin a oilproduction anddesperation forforeign

coupleofyears.Certainly thedecisionsto currencies. Gabon and Ecuadorhave ex-

reduce explorationand investment by tremely highproduction costs,Mexicois

otherswould come quickly,while the deepindebt,andEgyptimports foodwith

pricebenefitsto the Saudis would last oil earnings.Thesecountries wereamong

longer.17 thefirstto cutproduction. Otherhigher-

Second,theprincipalcost of coercion cost producers(Algeria,Qatar, Libya,

to theSaudisis thedomesticdislocation Venezuela,andNigeria)clamored forcuts

producedby budgetdeficits or low gov- to shoreup prices.Those who lost sig-

ernment revenuesthrough theimpactof nificant revenuesonlywhenoil pricesfell

cheapoil. TheSaudisareunabletogener- below$15 a barrel,likeIndonesia,Iran,

ate enoughrevenuewithoil at $10-$15 Iraq,and theUnitedArabEmirates (Wall

per barrelto meet projecteddomestic StreetJournal,11 February1986), were

expenditures, needingto produce7 mbd lessvocal.

todo so evenat theupperendofthisprice The key"allies"wereBritainand Nor-

range.In theshortterm,theywoulddraw way,whoneither cutproduction norindi-

againsttheirmassive($100-billion) cash catedwillingness to discussit. Therethe

reservebuiltup in theflushyearsafter loweroil pricemeantforegonegovern-

1978whileattempting to establisha repu- mentrevenuesand possiblepublicbor-

tation.In thelongterm,theyapparently rowingor increasedtaxes (both coun-

needto produceabout5 mbdat $22 per tries),reducedpublic investment (Nor-

barrel (on which theynet nearly$88 way),anda lowerexchange rate(Britain).

milliona day)to balancethebudget.Our Both countriesvoiced similarclaims.

calculationsabove show that this was Britishspokesmenclaimedthat90% of

unobtainableunder any nonreputation NorthSea oil can be producedat fiveto

strategy butjustpossible(perhapsaftera eightdollarsa barrel(WallStreet Journal,

yearor two) at theprice-quantity com- 11 February1986). The Norwegians

binationsarisingunder an established claimedthatoilwouldflowat fivedollars

reputation fortoughness, In any event, a barrel, concedingthat exploration

theSaudistwiceannounced"deferral" of wouldstopat thatprice(WallStreet Jour-

a budgetin 1986,announcements treated nal, 24 January1986). Later,theysaid

by someanalystsas evidenceof "weak- that they would follow Britain'slead

ness" (highcost of punishment). While (Wall StreetJournal, 11 February 1986).

thereis no evidenceof seriousdomestic These claims,foundedin fixedcostsof

unrest(eliteor popular),Saudi planners production withno further recoveryof

privately stress that they expected old investment (New YorkTimes,7 Feb-

demandfor oil to rise fasterat lower ruary1986),represent an effort to call a

pricesand thustherevenueimpactto be bluff.Theyare therealequivalent ofour

smaller.18 model's "challenge,"in the beliefthat

458

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HegemonicStability

Saudi production could not continueat ever,ifa hegemonic regime doesformas a

low prices. "mixedstrategy equilibrium," uncertainty

In factBritainand Norwayhad lessto aboutworldtrendswilllead to sporadic

loseintheshortrunthanmighthavebeen challenges fromallies(especiallyas con-

expected.Norway's public investment ditionschange) and possiblyultimate

loss willbe feltslowlyand was certainly collapse.

anticipatedby government planners.A

lower exchangerate would findmuch

supportamong Britishmanufacturers. Conclusion

The Thatchergovernment would not

want to raise domesticrevenuesin the We analyzeda game-theoretic model

runupto a generalelectionbut had two containing manyofthecentral features

of

yearsleftat thetime.19 The Britishalso hegemonicstabilitytheoryof regimes:

lacked controlover theiroffshoreoil asymmetry, distributionalconflict,costly

industry and maywellhavefeltthatany coercion,uncertainty, and instability.

cutstheymadewouldhavebeentoosmall Our resultsdependcruciallyupon the

to affectworldprices.Of course,itis also assumptions that(1) thereis incomplete

possible that impressingother OPEC information aboutthetrueabilitiesofthe

memberswas more importantto the hegemonand (2) thehegemonsometimes

Saudis thanany actualcutsobtainedin faces costs in coercingothersto coop-

NorthSea production. ThoughtheSaudis erate.Hegemonic instabilityin themodel

did relativelywell in the August1986 is a naturalconsequenceof uncertainty

negotiations, theysubsequently adopteda and mixedstrategies, whichrenderrepu-

softer position,acquiescinginproduction tationbothexploitable andchallengeable.

cutsto helpkeeppricesup. Withinour The model incorporates size differences

model,thiswould represent continuing amongparticipants by virtueof asym-

application ofa mixedstrategy, underthe metric information and asymmetric abili-

assumption that(domestic) costsofcoer- tiesto coerce.

cionhad becometoo largeto allowcon- Although the model uses specific

tinuedpunishment. As we notedabove, assumptions about the natureof uncer-

someevidenceis availableto supportthis tainty,it is importantto notice how

interpretation. generalin spirittheseassumptions really

In sum, potentialSaudi gains from are. The important factis thatthehege-

hegemony make theirinitiative compre- monknowsmoreaboutitsowncoststhan

hensible.In spiteofearlypredictions that allies know about the hegemon'scosts.

"the Britishwill talk, theyknow the No actor,noteventhehegemon, hasper-

Saudis can forcethepricedown"(Wall fect foresightabout futurecosts or

StreetJournal, 6 February 1986),a British actions.We haveemployed fairlygeneral

challengewas not necessarily irrational. distributional forms,and thereis no

Sinceequilibrium hegemonic regimes are reasonto believethatthesealoneaccount

possibleand the Saudis have enormous forthequalitative resultswe derive.Our

low-costreserves,theymay succeedin strongest assumption, really,is thatthe

establishing a hegemonic regime. Ifsucha hegemon andalliesareall completely cog-

regimeforms,theSaudisshoulddo well nizantof theinformation structureofthe

relativeto expectations based on perfect game, so thatdespitethe gaps in their

competition or alliancebehavior.If the knowledgethey can act strategically

regimedoesn'tformnow, thediscussion againstone another.The resultof this

ofhegemony in theprevioussectionsug- strategic interaction is expressedin our

geststhattheSaudiswilltryagain.How- resultson equilibrium in the hegemony

459

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 82

game.Sincetheequilibrium is Bayesian, regime willappeartofollowa rockyroad,

we have accountedforrationallearning with allies sometimeschallengingthe

by the players upon observingone hegemonand at othertimesobeyingand

anothers'actions. The expectationsof with the hegemonsometimesapplying

eachplayerareconsistent

withtheactions costlypunishments and sometimes acqui-

of theotherplayers.This equilibriumis escing.Equilibrium behaviorin thehege-

robust,thoughnotunique. monygamenecessarily implieshegemonic

instability.

Implications

forHegemonicStability usefulto realizethat

It is particularly

thebehaviorinvolvedin thisinstabilityis

Our resultshaveseveralimportant im- in no way attributable to "mistakes"of

plicationsforhegemonic stability

theory. anykindon thepartofanyoftheactors.

Most notably,althoughours is a result Only by contemplating mixedstrategies

about "stability"in thesenseof equilib- can theactorsbe satisfied thattheirown

rium,it demonstrates exactlyhowand in plans are consistent withtheirexpecta-

what circumstances hegemonicregimes tionsabouttheiropponents.Alliesocca-

mightbreakdownor appearunstable.In sionallychallengeand endurepunish-

situationslikecases 1 and 2, stabilityis ments,and the hegemonoccasionally

completeand lasting.In case 4 thehege- neglectsto punish,randomly butnotir-

mon getsno respectand punishesonly rationallyor unexpectedly. The natureof

whenit is costlessto do so. In a model hegemonic is thuspredictable

instability

with a more complexinformation and in the contextof the game-theoretic

cost structure,such behaviormightap- model.

pear as intermittent cooperationby the

allies,dependingon theinformation they Choicein HegemonicRelations

Effective

haveaboutthehegemon's costsinspecific

situations.Indeed,one can extendthis Several authors, notably Keohane

analysisto predictions ofdecliningsever- (1984),have drawnan analogybetween

ityof punishments over timeas a hege- regimesand cooperationin therepeated

mon's reputation becomesbetterestab- two-player prisoner'sdilemmagame.But

lished,as wellas predictions of therela- thisgame,evenwithadded assumptions

tive durabilityof hegemonicand non- of incomplete information (Krepset al.

hegemonic regimes.20 1982),does not reflect theeffects of size

More interestingly, in case 3 the ap- differences or asymmetricabilitiesto

pearanceof instability resultsfromthe punish.Thus manyof theresultsof our

incentivefora rationalally to challenge modelofreputation standinmarkedcon-

thehegemon.In addition,thehegemon trastto thebehaviorthatAxelrodiden-

punisheschallengesusinga mixedstra- tifies

as "effectivechoice"intheprisoner's

tegy;and theallyusesa mixedstrategy to dilemma(1984,chaps.6, 9).

decidewhether to respondto a previous First,a successfulprisoner'sdilemma

punishment.Thus, even though the playershouldpracticea "nice"strategy,

generalcostsand information parameters thatis,neverbe thefirst todefect.In con-

ofthegameremainconstant, theequilib- trast,a successful strategyforan allyin

riumstrategies call forpurposelyerratic the reputation game mustinvolvechal-

behaviorby hegemonand allies. Such lengingtheleaderaccordingto a mixed-

behavioris necessary to keepone'soppo- strategy plan. Failureto do so allowsthe

nentsguessingand (forthehegemon)to hegemonto taketoo muchadvantageof

take optimal advantageof the allies' thealliesbycommanding theirobedience,

learningprocess.The resultis thatthe even when they ought to have the

460

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HegemonicStability

strength to resist.Iftheregime consistsof dilemmaproblemstheirmembersface.

a hegemonenforcing mutually beneficial Thiswillnotbe a characteristic of hege-

collectiveaction, then such resistance monicregimes, in whichtheexistence of

maynot,overall,be advantageous. How- at leastsomeuncertainty is beneficial to

ever, if in the processthe hegemonis the hegemon.The hegemonwill dis-

demanding privatebenefits then seminateinformation

foritself, beneficialto it-

any successful challengeby an ally is to self,but repressinformation thatmight

theally'slong-and short-run gain. serveto informallies of the hegemon's

Second,a successful strategy in Axel- truecosts of punishing.The hegemon's

rod'sschemehad tobe "provocable," that incentive

topreserve others'uncertainty is

is, willingto retaliateagainstany trans- clearin theOPEC case discussedabove.21

gression.The successful hegemon, on the

otherhand,shouldinsomecircumstances

acquiesceto challenges fromitsallies.In OtherImplications and Extensions

cases1 and4 ofourdescription ofequilib-

rium,thisis obvious.Butevenin case 3, These resultsclearlydemonstrate the

whenthe hegemonis engagedin active potentialusefulness of advancedgame-

reputation building,theequilibrium stra- theoreticmodelsin the studyof inter-

tegyrequiresthe hegemonto acquiesce nationalrelations. Byexplicitly modeling

withprobability 1 - r if punishment is the sequentialfeaturesof the game (as

costly. Too much provocabilitywill advocatedby Snidal[1985b]and Wagner

weakenthehegemon'sabilityto builda [1983])and theincompleteness of infor-

reputation, becausetheallieswillregard mation,one can motivatesuchphenom-

punishment from a relatively"weak" ena as reputation and, in our case, in-

hegemon as beingso likelythatwhenthey stability.Behaviorpreviouslytreatedas

do observea punishment, theydo not extratheoretic "situational"featurescan

reducetheirestimates ofw byverymuch. thus be incorporated as endogenously

Third, Axelrod'sprescription that a arisingphenomenain a rationalactor

successful strategy be "simple,"thatis, model.This allows thestudentof inter-

easy foropponentsto detectand under- nationalrelations toanalyzereputation in

stand,mustbe qualifiedin an important thesamestrategic, rationalchoiceterms

way forthisreputation game.Bothhege- so usefullyapplied to the analysisof

monand alliesmustuse mixedstrategies cooperation and conflict.

undercertaincircumstances. Too much The generalnatureof the reputation

straightforwardness can reducea hege- problemmodeledheregives the results

mon'sabilitytocultivate a reputation and muchbroaderapplicability as well.Exam-

an ally's abilityto resistthe hegemon's ples can be foundin securitypolicyas

threats.Ifa hegemon is weak,thenbuild- wellas trade.22 Butapplications ofreputa-

ing a reputation requires that the hege- tionalmodels (and, by implication, hege-

mon cultivateratherthan alleviatethe monicregimes) arebyno meansrestricted

opponents'uncertainty.And benefit- to theinternational arena.Domesticap-

maximizing alliesmustnot allow sucha plicationsincludelegislativeleadership

hegemonto be completely confident that (Calvert 1987), predatorypricingand

a fewquickpunishments willscareoffall entrydeterrence in markets(Krepsand

future challengers. Wilson1982a),monetary policymanage-

Finally,Keohane(1984) suggeststhat ment(Barro1986), thepoliticsof labor

"collectiveaction"alliance-type regimes union relationswith management, and

formand disseminate information as a the between

relations a politicalparty and

majormeansofovercoming theprisoner's organizedinterest groups.

461

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 82

Some naturalextensions of themodel Appendix:Sketchof Proof and

couldyieldfurther interestingresults.As Propertiesof Equilibrium

noted above, allowing the actors to

receivespecificinformation about indi- This appendix describesthe steps

vidualsituations, thatis,aboutindividual neededto provethatthe description of

periodsinthegame,wouldfurther illumi- equilibrium foundin thetextis indeeda

natethenatureof hegemonic instability. sequentialequilibrium. Afterthat,it ex-

Especiallyforthispurpose,it would be plainsbriefly whyall reputation-building

usefulto allow a longerhorizonin our equilibriain thisgamerequiretheuse of

varyingcostsgame.Further, morecould mixedstrategies. More detailsare avail-

be learnedaboutthekindsofcooperation able fromtheauthorson request.

thata hegemon canachieveifwe modeled We will use the followingadditional

reputation withinthecontextofa collec- notation:Let q be the probability with

tiveactiongame,withthepossibility that whichally1 challenges. LetSo, sA, andsp

the hegemon'spunishments may be im- represent theprobability withwhichally

possibletofocuson a particular offender, 2 challenges giventheoutcomeofperiod

as is trueintheoil priceconflict described 1: obedience, acquiescence to a challenge,

above. Sucha modelmightalso illustrate and punishment of a challenge,respec-

cooperationproblemsfaced by allies, tively.Let ro be the probabilitywith

who couldjoin together in smallercoali- whichthehegemonpunishesa challenge

tionsto challengethehegemon.Finally, by ally1 ifpunishment is costless;r1the

assuminguncertainty on the hegemon's probability of punishing ally 1 ifcostly;

partabout theallies' costs and benefits and r2theprobability ofpunishing a chal-

would further clarifythe natureof the lengeby ally 2 if costless(obviouslyno

allies'strategic opportunities. costlypunishment is everrationalin the

Even withoutthesefurther considera- finalperiod).LetPi be ally1's subjective

tions,ourmodelhasa number ofinterest- probability of punishment, a function of

ingfeatures. It subsumesa dimension of thehegemon's strategy(roandri).Finally,

conflict froman empire(inwhicha hege- let po, p2p, and p2 be ally 2's subjective

moneasilymonitors opponents' behavior probabilities of being punished,condi-

and punishescostlessly, obtaining nearly tionalon theoutcomeofperiod1.

all thegainsfromitsregime) toan alliance Firstnotethat,in all fourof thecases

(in whicha hegemonmay so value the (rangesof b) describedin thetext,sA >

good producedby theregimethatit is sp; thereforero = 1 since a costlesspun-

providedpractically regardless of coop- ishment in period1 has a positivedeter-

eration,sharingbenefits widely).Evenat renteffect. Notealso thatthehegemon is

themarginofthesepolartypes,as wellas indifferentabout punishingin period2

anywherein between,thereis room to whenitis costlesstodo so; therefore r2=

createand exploitreputation. Similarly, 1 is acceptable.It remainsto derivebest

themodelimpliesthatalliesdo notchal- responsefunctionsforq, r1,so, SA,and sp.

lengesimplyforthesake of finding out Step1 is to derivethehegemon's basic

thehegemon'struenature.And, indeed, responsefunction forr1.This is accom-

themodelemphasizesthehegemon'sin- plishedfairlysimplybywriting thehege-

centivetolimitthedissemination ofinfor- mon'sexpectedutilityfortheremainder

mationin orderto continueexploiting ofthegamefromusingr1,giventheother

uncertainty, as wellas to continuetrying players'strategies, whenally 1 has just

(whilealliescontinue probing)to createa challengedanditis costlytopunish.Then

regimeexploitingreputationaleffects. maximizethisexpression withrespectto

Further extensions and applications r1.

shouldproverewarding. Step2, theeasiest,is to deriveallyi's

462

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HegemonicStability

best responseforq, givenr1,again by equilibria canbe ruledoutbyputting con-

maximizing ally1's expectedutility. ditionson the"reasonableness" ofbeliefs

Step3, calculating ally2's bestresponse in equilibrium (see Calvert1987).

functions, is a bit moreinvolved.First, Third,thehegemonis freeto maker1

calculatep0, pA, and pipusingrl,a, and (or r2,forthatmatter)dependupon w

fi.Noticethatally2 mustusetheprevious ratherthanbeingconstant.23 Sucha strat-

moves,alongwithr1,to updatethesub- egywouldrequirethatbothalliesalso use

jectivedistribution of W accordingto different strategies, even if theexpected

Bayes'rule.Next,foreach outcomeh e valueofr1is stillr. To see why,consider

{ 0, A, P} use thecalculatedvaluesofph ally i's expectedpayoffwhentheprob-

towriteally2's expected utilityfromchal- abilityof punishment, when costly,is

lengingwithprobability Sh. Finally,for QLO(W):

each h maximizeally2's expectedutility

withrespectto shgivenr1. E{[1 - Q1(W]Wb

Finally,step 4 is to look at the four + [1 -W + WeQ(W)](b -1)}.

cases of therangeof b, verifying in each

case thatthestrategies givenin thetext Since E[We1(W] * EW . EQ1(W), the

simultaneously satisfyall the best re- payoffs toally1'sresponses canbe chang-

sponsefunctions calculatedin steps1-3. ed whilekeepingEeL(W = r.Similarrea-

Thisprovesthatthegivenstrategies form soningappliesto ally2. Thisgivesriseto

a Bayesianequilibrium. a largesetofalternative equilibria;how-

In provingthatthisBayesianequilib- ever,all oftheminvolvetheuse ofmixed

riumis a sequential equilibrium, onlycase strategies by ally 2. Althoughthehege-

2 causesa problem:ifally1 unexpectedly mon's strategy is technically pure,itlooks

challengesand if the hegemonunex- toanyobserver, including theanalystand

pectedlyacquiesces, then the denom- ally2, likea mixedstrategy sincethetrue

inatorin Bayes'formula is undefined and valueofw is unobservable.

we cannotcalculatepAand deriveally2's Fourth, sincethehegemon is indifferent

bestresponse.Thisis remedied bysetting about applying a costless punishment in

pA= f3/(a + ,3 + 1); such a beliefis pro- the final period, there are other equilibria

ved consistent by usingthefollowing se- in whichr2< 1. We mightimaginethat,

quenceof strictly positivestrategies for therebeingno realfinalperiod,thehege-

thehegemon:foreachn = 1, 2, . . ., let monreallywouldhave a positiveincen-

rO= 1 - 1/n2,and let r n = 1- 1/n. tiveto punishcostlessly. Thisamountsto

(Fordefinitions of thesetermssee Kreps addinga (small)positivepayoff e forsuch

and Wilson1982b.) "costless"punishments. Such a payoff

There are other, more complicated eliminates thepossibility thatr2< 1, but

equilibria in this game that also exhibit now, as itturns out, r1 is forced todepend

reputation building.All of them,how- on w. Equilibrium can stillbe derived

ever,involvemixedstrategies. Alterna- usinga similarproof,but thedetailsare

tive equilibriamay arise in fourways: considerably morecomplicated (contrary

First,trivially, at the of

boundaries cases to the conjecture in Calvert 1987).

1, 2, and 4, somemixed-strategy equilib-

ria mayalso arisedue to theindifference

of a playerbetweentwo purestrategies. Notes

Second, thereare "mirror-image" equi-

libriainwhichally2 setsSA < sp incases theAn earlierversionof thispaper was deliveredat

1986 annual meetingof the Midwest Political

2 or3, andthehegemon mustacquiescein Science Association, Chicago. The authorsbenefit-

orderto "deter"ally 2. Such perverse ted fromthe commentsof David Baron, JohnFere-

463

This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Mon, 16 Sep 2013 04:08:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 82

john, Robert Keohane, David Laitin, Ian Lustick, mon than by its allies. This generalsituation,the

JamesMorrow, Michael Munger,KennethShepsle; "chain storeparadox," was firstanalyzed by Selten

fromthe internationalrelationsworkshops at the (1975, 1978).

Universityof Illinois and the Hoover Institution, 8. The beta distributionis a flexibledistribu-

Stanford;and fromthepoliticaleconomyworkshop tionalformon theunitinterval.It describesthelimit

at WashingtonUniversity.We are gratefulfor the of infiniterepeatedsamplingfroma Bernoulli(zero

supportof the National Science Foundationunder or one) population. When samplingfrom such a

GrantSES85-12037. populationwithprobabilityw of obtaininga "one,"

1. Whether applied to international trade, the beta distributionhas parameters(x and ,3 such

finance,or defense,the"theoryof hegemonicstabil- that its mean, E(W) is equal to ca/(a + p3).The

ity" holds thatregimessurviveonly if backed by a variance of W is aci/l(ca + 3)2(ci+ 3 + 1)]. The

hegemonicpower. values of ca and is may be any positive numbers

2. By assumingthe initial asymmetryof hege- (DeGroot 1970, 35). To grasp the roles of ca and A,

mon and ally and explicitlymodelingthe strategic considerBayes' ruleforupdatinga beta prior.If the

problemof thehegemonin achievingand maintain- initialparametersare (a,,() and a "one" is observed,

ing a reputationforwillingnessto engage in costly a becomes a + 1, increasingthemean; ifa "zero" is

retaliation,thepresentstudygoes beyond theexist- observed,,3becomes,3 + 1, decreasingthemean. In

ing internationalrelations literatureon "threat a loose sense,then,a givesthenumberof "1's" and fi

power"(Bramsand Hessel 1984), "capability"(Maoz the numberof "0's" in previousobservations.

1983) and "resolve" (Allan 1983; Cioffi-Revilla 9. An ally in case 2 who began withan estimate

1983). of w just below the upper thresholdwould assume

3. For instance,SteinremarksthatKindleberger, that acquiescence indicateda high cost of punish-

Gilpin, and Krasner "all mentionthat a hegemon ment.It would therefore add one to ca,givinga new

uses inducementsand force.... The hegemonmust estimateof w = 03/(c+ ,3 + 1), whichis by defini-

get othersto agree. . . . Withoutagreementsthere tionof thiscase less thanb, so it would now be pre-

can be no regime.Such accords typicallyrequirethe pared to challenge.

hegemon to make importantconcessions" (1984, 10. Althoughours is not the unique equilibrium

356-59). in thisgame,all but one of theothersalso requirethe

4. An influentialearly example is Schelling use of mixedstrategies.See theAppendix.

(1960, esp. 24-27, 119-50), and regime stability 11. Their model, too, requiresthe use of mixed

theorists have often taken the same approach strategiesin equilibrium.There, also, the oppor-

(Downs, Rocke, and Siverson1985; Jervis1985, 61, tunitiesforreputationbuildingvarywiththegame's

69, 73-78; Snidal 1985a, 600; Snidal 1985c, 931). parameters;and theresultshold withany combina-

5. Our modelis a generalizationof thatofKreps tionof severalallies, each makingseveraldecisions.

and Wilson (1982a) for the special case of a two- 12. For instanceassume initialvalues of two for

period game, as explained below. Every game of each of ca and j3, so that E(W) = .5 initially(the

incompleteor asymmetricinformationessentially cutoffbetweencases 2 and 3) and the boundaryof

involves problemsof reputation.Some of the eco- case 4 = .6 (see Figure2). Assumean ally'spayoffof

nomic theory literatureclosest to our concerns .58, puttingthisally squarelyin case 3. Then, after

includes: Fudenbergand Kreps 1985 on reputation several observations of punishmentand acqui-

buildingby a monopolistfacinga varietyof poten- escence,both a and j3could have increasedby two,

tial competitors;Rubenstein1985 and Grossman leavingE(W) unchangedat .5, butreducing(a + 1)/

and Perry 1986 on bargainingunder asymmetric (a + , + 1) to .55, placingtheally in case 4 (always

information;Sobel 1985 on the establishmentof challenge).

credibilityin ongoingsignalinggames; and Fuden- 13. For example,thehegemonmay lose itsasym-

bergand Tirole1986 on a "war of attrition"in which metricalabilityto punish,as describedforexample

two duopolists attemptto convince each other to by Keohane (1984, chap. 9). Or thecollectivegood

exit from an industrythat cannot support them producedand distributed by theregimemay lose its

both. value. Allies can observethesechangesand become

6. We treattheseallies as two different

players, aware thatrandomshocksare now morelikelythan

although in fact our model does not distinguish beforeto put an end to theregime.

betweentwo allies, each makingone decision,and a 14. This is an aggressivestrategy,but theirpre-

single ally making two decisions sequentially.See vious exploitationwithinOPEC shows thatalterna-

Calvert1987. tive "nicer"side-paymentstrategieswould not suc-

7. Formally,each xt has the Bernoullidistribu- ceed in inducingcooperation,nor would any alter-