Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Perceptions of FASD Among School Superintendents in Minnesota

Transféré par

fasdunitedCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Perceptions of FASD Among School Superintendents in Minnesota

Transféré par

fasdunitedDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

ISSN: 2378-3001

Brown et al. Int J Neurol Neurother 2017, 4:068

International Journal of DOI: 10.23937/2378-3001/1410068

Volume 4 | Issue 2

Neurology and Neurotherapy Open Access

Short Review Article

Perceptions of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) among

School Superintendents in the State of Minnesota

Jerrod Brown1,2,3*, Donald Helmstetter1, Diane Harr1 and Jeff Louie4

1

Concordia University, St. Paul, MN, USA

2

Pathways Counseling Center, St. Paul, MN, USA

3

The American Institute for the Advancement of Forensic Studies, St. Paul, MN, USA Check for

updates

4

University of Minnesota, Department of Pediatrics, Minneapolis, MN, USA

*Corresponding author: Jerrod Brown, Ph.D., MA, MS, Pathways Counseling Center, 1919 University Ave W Suite 6 St.

Paul MN, 55104, St. Paul, MN, USA, E-mail: jerrod01234brown@live.com

impulsivity), social (e.g., communication including ver-

Abstract

bal and non-verbal language), and adaptive (e.g., deci-

Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) of- sion-making, problem-solving, and ability to learn from

fer unique challenges in school and other settings. As such,

administrators such as district superintendents, many of experience) impairments [3-6]. In education settings,

whom make recommendations for long-term suspensions deficits in short- and long-term memory and the capac-

or expulsion, need to be prepared to work with students ity to learn may be the most noticeable [7-9]. Deficits in

with FASD. This requires familiarity with FASD screening, the encoding, retrieval, and application of memory [10]

knowledge of FASD intervention and teaching strategies,

and possession of a plan for referring these students for ad-

can impact verbal and non-verbal learning, mathemat-

ditional assistance. Unfortunately, little is known about how ics, and the identification of odors and colors [11,12].

familiar school superintendents are with FASD. To this end, Because these symptoms can vary widely as a function

a Web-based qualitative survey concerning FASD was ad- of the timing and amount of prenatal alcohol exposure,

ministered to school superintendents. This study found that FASD often goes unrecognized, undiagnosed, and sub-

superintendents vary in their (a) Ability to accurately identify

signs and symptoms of FASD and (b) Awareness of unique sequently untreated in school children.

psychoeducational impairments experienced by these in- Diagnosis is further complicated in at least three

dividuals. Superintendents believe they would benefit from

continuing education in the psychoeducational impairments

ways. First, individuals with FASD typically do not have

of individuals diagnosed with FASD and a form or checklist visible indicators of the disorder such as physical de-

to assist them in their decision-making process. formities. Second, many of the associated impairments

Keywords can be, and often are, superficially masked by the in-

dividual. This is particularly true over short periods of

FASD, Education, School superintendents, Special educa-

tion, Training

time in comparison to longer ones that allow for more

observation as part of a long-term relationship. For ex-

ample, individuals with FASD may mask the disorder by

Introduction scoring in the normal range on intelligence tests or pre-

Afflicting 2-5% of the U.S. population [1], Fetal Al- senting with adequate verbal intelligence. However, dif-

cohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is not an easily recog- ficulties in global functioning tend to become apparent

nized disorder. Caused by Prenatal Alcohol Exposure over longer periods of interaction [13,14]. Third, almost

(PAE) and its associated brain damage [2], FASD can all individuals with FASD have at least one co-occurring

present in a variety of ways. This can include cognitive mental disorder [12]. In fact, one study estimated that

(e.g., executive control, learning, memory, attention, and this was the case for over 90% of individuals with FASD

Citation: Brown J, Helmstetter D, Harr D, Louie J (2017) Perceptions of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

(FASD) among School Superintendents in the State of Minnesota. Int J Neurol Neurother 4:068. doi.

org/10.23937/2378-3001/1410068

Received: August 18, 2017: Accepted: October 31, 2017: Published: November 02, 2017

Copyright: 2017 Brown J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction

in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Brown et al. Int J Neurol Neurother 2017, 4:068 Page 1 of 8

DOI: 10.23937/2378-3001/1410068 ISSN: 2378-3001

[15]. Common comorbid disorders include behavioral as a student with FASD, the district should identify an ad-

(e.g., Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), vocate for the student. Ideally, this should be an education

conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder), professional that has made a strong connection with the

mood (e.g., depression and mania), substance use, student. This advocate has the task of ensuring that teach-

trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and ers are aware of the students strengths and weaknesses

learning disorders [2,15-18].When not accurately iden- throughout transitions in the educational process. Third,

tified, FASD typically goes untreated in school children, school district administrators can help ensure that staff is

perpetuating a host of learning deficits and inappropri- familiar with the best available strategies and techniques

ate behaviors that can impinge on social development. for educating this challenging population. Further, these

administrators have the opportunity to help address be-

Outside of immediate family, educators typically spend

havioral problems in ways that limit the development of

more time with the child than almost anyone else. Al-

long-term consequences such as expulsion. Throughout

though educators typically have a limited recognition and

this process, this team should involve mental health and

understanding of FASD, teachers and other district staff are

social services professionals when appropriate to maxi-

in a vital, unique, and influential position to recognize the

mize the effectiveness of interventions.

challenging symptoms of FASD through their daily student

interactions. Empowering teachers to recognize and refer Superintendents, and their district staff, receive limited

students to appropriate qualified professionals significant- education and training about FASD and its impacts within

ly increases the likelihood of positives outcomes for all the education system. At present, research is inconclusive

students with FASD. When FASD is suspected, the student on the efficacy and Return on Investment (ROI) that results

should be referred to an educational assessment team for from providing treatment to these students. It is believed

multidisciplinary planning and potential formalized assess- that when this student population is supported with ade-

ment. Such an endeavor should incorporate information quate resources their long-term outcomes like school per-

from family and teachers on the students strengths and formance, social functioning, and problematic behaviors

weaknesses. Thorough and accurate diagnosis is critical to will dramatically improve. District staff at all levels can ben-

informing the development of treatment and case man- efit from better understanding and awareness about FASD

agement plans for the student. As always, early interven- and how it impacts the lives of those students with FASD.

tion provides students with the best chance for long-term

success and the minimization of consequences across the

The present study

lifespan [19-21]. The purpose of the present study is to determine how

well educators understand FASD. Because top-level ad-

The cost of FASD going unrecognized within students

ministrators are often tasked with important decisions

is not simply monetary. Students with FASD often exhibit

including long-term suspension and expulsion, school su-

lower rates of achievement [15] with a higher likelihood of

perintendents are the focal point of this study. This is an

truancy, behavioral problems, and failure to graduate rela-

understudied area, as the authors were unable to identify

tive to students without FASD [7,15,22]. Further, students

any existing publications worldwide that explore this topic

with FASD can be more challenging to instruct and require

among school district superintendents. The current study

increased resources in comparison to other non-FASD stu- focused specifically on the state of Minnesota school dis-

dents. Specifically, students with FASD may respond incon- trict superintendents.

sistently to traditional teaching and disciplinary methods.

For example, a student with FASD may respond positively The authors hypothesized the following:

to a technique in one instance but respond negatively to 1. School superintendents, while possibly having a basic

the same technique in another instance. To prevent such understanding of FASD, will not have an advanced un-

frustrations, teachers may benefit from considering strat- derstanding of the specific characteristics of FASD.

egies that have been found successful with students who

2. School superintendents have not received training on

have other special needs. The success of teachers in re-

neurobehavioral impairments as they relate to FASD.

sponding to the diverse challenges of students with FASD

holds promise in improving the academic success of these 3. School superintendents believe that he or she would

students [19,20,21,23]. benefit from having the findings of an FASD screening

tool as part of their daily practice.

The key to improving outcomes for students with FASD

may be the incorporation of a team approach. In addition Method

to parental involvement, a network of dedicated teachers,

advocates, and school administrators all have important

Procedure

roles to play. First, teachers will always be at the forefront The Perceptions of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

of these efforts. Teachers can play an integral role in iden- (FASD) among School Superintendents in the State of

tifying students who may have FASD, ensuring referral for Minnesota was created as an online Google Sheets form.

proper assessment, and finding ways to improve the effec- Responses were collected in a Google Sheets document

tiveness of their learning program. Second, once identified and analyzed using SPSS 22 [24]. The survey was distrib-

Brown et al. Int J Neurol Neurother 2017, 4:068 Page 2 of 8

DOI: 10.23937/2378-3001/1410068 ISSN: 2378-3001

uted electronically to all superintendents in Minnesota

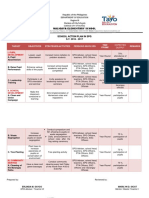

(N = 325) by the Minnesota Association of School Ad- Participant Gender Counts

ministrators (MASA). After the initial recruitment email, 100 93

90

weekly reminders were sent for a one-month period to 80

prompt superintendents to participate in the study. In- 70

60

formed consent was assumed by completion, or partial 50

completion of the survey. Study was approved by the 40

25

Institutional Review Board, University of Minnesota. 30

20

10

Measure 0

Male Female

The survey consisted of 13 closed-ended response

questions and 1 open-ended comments question re- Figure 1: Participant gender counts.

garding participant assessments of FASD. The survey

consists of 14 items, with 10 being relevant to FASD and

4 demographic questions. Demographic variables col- Count by Region

25

lected were: 1) Years since obtaining Minnesota Admin- 23

istrative License, 2) Gender, 3) MASA Region, 4) Com- 20 18

ments. Frequency distributions were calculated for the 15 14

15

13

12

nominal answers provided. 9

10 8

7

Questions 5

1. What percentage of individuals diagnosed with Fe- 0

tal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder have facial abnormal- Region Region Region Region Region Region Region Region Region

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

ities such as wide set eyes, thin upper lip, smooth

Figure 2: Counts of participants by region.

philtrum, upturned nose, epicanthal folds, and small

head size?

trum Disorder (FASD) in your daily practice?

2. What percentage of individuals diagnosed with Fetal

Alcohol Spectrum Disorder become involved in the 11. Years since obtaining MN Administrative license

criminal justice system? (years)?

3. Have you ever received training on the neurobehav- 12. What is your gender?

ioral impairments experienced by individuals diag- 13. What is your MASA region?

nosed with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder?

14. Additional Comments?

4. How recently was this training received?

5. What do you recall from this training as to the edu-

Results

cational developmental impairments experienced by Respondents

individuals diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum

Disorder (FASD)? Of the 325 online survey requests sent, 37% (n = 120)

responded with at least a partially completed submis-

6. What do you recall from this training as to the be- sion. Of respondents who completed the gender varia-

havioral developmental impairments experienced by ble (n = 118), 21% were female (n = 25) and 79% were

individuals diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum male (n = 93) as shown below in Figure 1.

Disorder (FASD)?

Nine educational service regions were established in

7. In your experience as a school administrator, has the 1976 by the Minnesota Legislature to provide cost-ef-

behavior of a student identified with Fetal Alcohol

fective, high quality education services and programs to

Spectrum Disorder (FASD) been as significant as to

public schools/districts, private schools and nonprofits.

necessitate your involvement?

Of the 119 responses by region, region 3 had the most

8. Are you aware of any administrator in your system responses at 23 (19%), followed by region 1 at 18 (15%),

who knows as much or more than you do about Fetal region 8 at 15 (12%), region 6 at 14 (12%), region 9 at

Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)? 13 (11%), region 5 at 12 (10%), region 4 at 9 (8%), region

9. Would you likely benefit from a continuing educa- 7 at 8 (7%) and region 2 at 7 (6%) as shown below in

tion course on the neurobehavioral impairments of Figure 2.

individuals diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Of all 120 superintendents surveyed, almost 90%

Disorder (FASD)? had their administrative license between 5 and 10 years

10. Would you likely benefit from being provided the (n = 24, 20%) or more than 10 years (n = 83, 69%) as

findings of a screening tool for Fetal Alcohol Spec- shown below in Figure 3.

Brown et al. Int J Neurol Neurother 2017, 4:068 Page 3 of 8

DOI: 10.23937/2378-3001/1410068 ISSN: 2378-3001

Years Since Licensure Neurobenavioral Impariments Tranining Received

90 83

80 73

80 70

70 60

60 50 42

50

40

40

30

30 24

20

20

10 4 5 10 5

1 3

0 0

<1 1-2 2-3 3-4 5-10 > 10 Yes No I dont know

Figure 3: Years since licensure. Figure 6: Count of participants regarding having received train-

ing on neurobehavioral impairments experienced by those with

FASD.

% of FASD Individuals with physical

abnormalities

How recently was training received?

30 26

23 80

25 72

19 70

20

15 12 60

10

10 8 50

5 6 5

3 37

5 40

0 30

20

%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

%

%

00

20

10

8

-3

-4

-7

-8

-9

-5

-6

-1

10

-

0-

21

31

61

71

81

41

51

11

91

2

0

Figure 4: Percentage of individuals with FASD believed by

< 1 year 1-5 years 5+ years No trining

participants to have physical abnormalities.

Figure 7: How long since receiving training on neurobehavioral

impairment experiences of those with FASD.

% FASD became crim justice involved

25

believed between 61-70% (n = 21, 18%) followed by 21-

19

21

30% (n = 19, 16%), with 31-40% and 51-60% each receiv-

20

16 16 15 ing the same total (both n = 16, 14%), 71-80% (n = 15,

15

10

13%), 11-20% (n = 10, 9%), 41-50% (n = 9, 8%), 0-10% (n

9

10

6

= 6, 5%), 81-90% (n = 3, 3%), and 91-100% (n = 1, 1%) as

5 3

1

shown below in Figure 5.

0

Educators are in a unique position to positively im-

%

pact those students who have FASD. As they gain ac-

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

%

00

10

-3

-4

-7

-8

-9

-5

-6

-2

-1

21

31

61

71

81

41

51

11

0-

91

curate knowledge about identification and potential

Figure 5: Counts of participants by percentage block of individ- implications, education professionals can also more ac-

uals with FASD that participants believe will come into contact curately intervene on behalf of their students.

with the criminal justice system at some point in their lives.

Training

FASD diagnostic knowledge Participants were also asked if they had received any

Participants were asked a number of FASD related training on neurobehavioral impairments experienced

questions including what percentage of individuals with by individuals diagnosed with FASD. The overwhelming

FASD they believed had facial abnormalities (e.g., wide- majority of 120 responses selected No (n = 73, 61%),

set eyes, thin upper lip, smooth philtrum, upturned followed by Yes (n = 42, 35%) and I do not know (n

nose, epicanthal folds, and small head size). Of 117 re- = 5, 4%) as shown below in Figure 6.

spondents, the largest group believed between 21-30% A follow-up question queried, How recently was

(n = 26, 22%) followed by 0-10% (n = 23, 20%), 11-20% this training received? Of the 119 responses, the ma-

(n = 19, 16%), 41-50% (n = 12, 10%), 31-40% (n = 10, jority replied that I have never had training (n = 72,

9%), 61-70% (n = 89, 7%), 81-90% (n = 6, 5%), 51-60% & 60%), followed by over 5 years ago (n = 37, 31%), 1-5

91-100% each receiving the same total (both n = 5, 4%), years ago (n = 8, 7%) and less than 1 year ago (n = 2 and

and 71-80% (n = 3, 3%) as shown below in Figure 4. 2%) as shown below in Figure 7.

Participants were also asked what percentage of in- A third training related question asked, What do you

dividuals with FASD will become involved in the criminal recall from this training as to the educational developmen-

justice system. Of 116 respondents, the largest group tal impairments experienced by individuals diagnosed with

Brown et al. Int J Neurol Neurother 2017, 4:068 Page 4 of 8

DOI: 10.23937/2378-3001/1410068 ISSN: 2378-3001

Educational Developmental Impairments FASD Neccessitated Involvement

Experienced 70 62

73

80 60

70 50

60

50 36 50

40

30

20 2 2 1 0

6 40

10

0

30

..

.

r..

l..

..

..

e

nd

al

um

..

as

na

ve

20

m

ic

la

le

ne

tio

ul

lin

er

,p

ga

ic

a

nt

e

C

er

uc

av

Le

r

Lo

ur

th

Ed

Ih

10

C

O

If

0

Figure 8: Count of participants regarding what they recall about

Yes No If other please provide

the educational developmental impairments experienced by in- your response

dividuals with FASD.

Figure 10: Count of participants that needed to get involved due

to the behavior of a student with FASD.

Behavioral Developmental Impairments Experienced

45

40

41

Knowledgeability

35 80 76

30 26 70

25

20

60

15 50

10 38

5 5 40

5 2 2

0

30

20

Figure 9: Count of participants regarding what they recall about

10 4

the behavioral developmental impairments experienced by indi-

0

viduals with FASD. Yes No If other please provide

your response

FASD? Of 120 responses, the most common response Figure 11: Count of participants regarding their knowledge abil-

was I have never had training (n = 73, 61%), followed by ity in relation to others about FASD in their district.

Educational impacts of FASD in school age children (n =

36, 30%), If Other, please provide your response (n = 6, CE Course Beneficial?

5%), with Clinical background of FASD and Curriculum 90 84

regarding FASD prevention, identification, and care each 80

70

receiving the same total (n = 2, 2%), Legal and policy is-

60

sues surrounding FASD (n = 1, 1%), and Long term plan- 50

ning for students with FASD not being selected at all (n = 40 32

0, 0%) as shown below in Figure 8. 30

20

The final training related question was, What do you 10 4

recall from this training as to the behavioral developmen- 0

Yes No I dont know

tal impairments experienced by individuals diagnosed with

FASD? Of 81 responses, the most common response was Figure 12: Would a CE course be beneficial to you?

Educational impacts of FASD in school age children (n =

41, 51%), followed by If Other, please provide your re- responses to In your experience as a school administrator

sponse (n = 26, 32%), with Clinical background of FASD has the behavior of a student identified with FASD been

and Long term planning for students with FASD each re- as significant as to necessitate your involvement? were

ceiving the same total (n = 5, 6%), and Curriculum regard- almost evenly split. Of 120 responses, Yes was selected

ing FASD prevention, identification, and care and Legal most often (n = 62, 52%) followed by No (n = 50, 42%)

and policy issues surrounding FASD each receiving the and Other (n = 6, 7%) as shown below in Figure 10.

same total (n = 2, 3%) as shown below in Figure 9. There were 118 responses to Question 8: Are you

Professional development and training opportunities aware of any administrator in your system who knows

which address recognition and planning for education- as much or more than you do about FASD? No (n =

al and behavioral needs of students with FASD should 76, 64%) was selected most often. This was followed by

be a comprehensive part of academic institutions. Evi- Yes (n = 38, 32%) and Other (n = 4, 3%) as shown

dence-based practices should be integrated with curric- below in Figure 11.

ulum and instruction in an effort to improve educational There were 120 responses to Question 9: Would

outcomes. you likely benefit from a continuing education course

on the neurobehavioral impairments of individuals di-

Professional experience with FASD agnosed with FASD? The majority selected Yes (n =

The last four questions of the survey dealt with profes- 84, 70%). This was followed by I dont know (n = 32,

sional experiences of superintendents regarding FASD. The 7%) and No (n = 4, 3%) as shown below in Figure 12.

Brown et al. Int J Neurol Neurother 2017, 4:068 Page 5 of 8

DOI: 10.23937/2378-3001/1410068 ISSN: 2378-3001

volvement of individuals with FASD. In this study, only

Screening Tool Beneficial 44% believed that at most 40% of those with FASD

80 75

would enter the criminal justice system in some capaci-

70

ty. In contrast, research has found that the actual prev-

60

alence rate of criminal justice-involvement by individ-

50

40 uals with FASD may exceed 60% [15]. However, it was

30

28 noteworthy that a second group consisting of 31% of

20 16 the sample estimated that 61-80% of individuals with

10 FASD would become involved in the criminal justice sys-

0 tem. This gap in estimates between these two groups

Yes No I dont know

indicates an area appropriate for increased funding, re-

Figure 13: Would an FASD screening tool be beneficial to search, and training.

you?

Training

There were 119 responses to Question 10: Would Training helps increase awareness and knowledge of

you likely benefit from being provided the findings of a FASD. It also assists in increasing the effectiveness of dis-

screening tool for FASD in your daily practice? Again, trict resource allocation at the highest levels of district

the majority selected Yes (n = 75, 63%). This was fol- administration. Over half of the 120 respondents 61%)

lowed by I dont know (n = 28, 24%) and No (n = 16, reported never receiving any training on the neurobe-

13%) as shown below in Figure 13. havioral impairments experienced by individuals with

No single professional is capable of knowing everything FASD. For the minority of respondents that received

about all of the critical issues confronting educational some form of training, the training they had received

leaders on a daily basis. Further, even if that leader has typically took place over 5 years ago. With a gap in train-

had training in the past, she or he cannot be expected to ing of at least 5 years, the science and understanding in

remember all the information that could help in making the field may have dramatically shifted. To increase the

a quality, timely decision. One possible solution is the efficacy of training, it must remain timely and relevant.

development of a screening tool that can help educa- Among respondents who had had some training, al-

tors more effectively identify students who may have most 90% (n = 41) recalled the educational developmen-

FASD. An FASD-specific screening tool utilized within tal impairments of FASD in school age children. Similar-

school settings could be extremely helpful for educa- ly, the vast majority of respondents (75%) recalled be-

tional professionals by helping guide and inform deci- havioral developmental impairments of FASD in school

sion-making with greater confidence. age children. In contrast, no one (0%) could recall long-

Discussion term planning for students with a FASD. Similarly, very

few could recall training content on legal and policy

Response rate from the survey was strong at 37% issues (1%), clinical background (2%), or identification

with of ratio of nearly 4 male participants (n = 93, 79%) and treatment (n = 2, 2%) on FASD. These disparities

to each female participant (n = 25, 21%). This ratio tends point to possible areas for improvement in the training

to indicate there are substantially more males serving as provided to school district staff.

superintendents in the state of Minnesota. Additionally,

the greater majority (n = 107, 90%) of respondents had Despite the promise of improved trainings, such pro-

held their administrative license for 5 or more years. grams would not be a panacea. Although most respond-

ents believe that a continuing education course on the

FASD diagnostic knowledge neurobehavioral impairments of FASD would be helpful

(70%), a sizable minority (27%) were uncertain that such

FASD is often considered an invisible disorder be-

training would be helpful. Similar results were observed

cause those impacted rarely present physical indica-

when respondents were asked about the potential use

tors that would betray their condition(s). Even if de-

of a FASD screening tool in daily practice. These results,

formities are present at birth, children tend to outgrow

although not initially intuitive, could be due to the se-

them as they mature making visible identification more

vere lack of timely and relevant training to make the

challenging [25,26]. Unfortunately, only about 30% of

information both actionable and valuable along with

respondents recognized that children with Fetal Alco-

other logistical and practical time constraints.

hol Spectrum Disorder typically do not have physical

deformities such wide-set eyes, thin upper lip, smooth Professional experience with FASD

philtrum, upturned nose, epicanthal folds, or a reduced

Based on this survey, just over half (52%) of Minne-

head size. Until such perceptions are changed, FASD will

sota superintendents appear to have been personally

likely persist as an under-identified disorder.

involved with significant behavioral concerns of FASD

This missed or inaccurate diagnosis of FASD may students. This striking figure reinforces the perception

contribute to the underestimation of criminal justice-in- that FASD behavioral cases are rising to the highest lev-

Brown et al. Int J Neurol Neurother 2017, 4:068 Page 6 of 8

DOI: 10.23937/2378-3001/1410068 ISSN: 2378-3001

els of district administration throughout the state. As essential in the identification of evidence based practices

a result, superintendents overwhelmingly agree that and best practices in this area. For example, survey results

continuing education (70%) and availability of a FASD may be informative in gauging the utility of employing

screening tool (63%) would be beneficial in handling trauma-informed care approaches in students with FASD.

such cases. Third, the findings from such survey work can be used to

inform the development and refinement of FASD-related

An informed, collaborative approach to understanding

training programs for educational and other professionals.

and intervening will help educators and families meet

Such endeavors could explore if ND-PAE criteria can alle-

the complex needs of students with FASD. Providers

viate issues related to missed and inaccurate diagnosis of

from areas of mental health, social services, develop-

FASD. As laid out in this section, a systematic and nuanced

mental disabilities, and law enforcement allow for pro-

approach to exploring the varied understanding of FASD

vision of interventions that draw upon expertise within

has the potential to improve outcomes for those with the

the schools and surrounding community. Early diagno-

disorder.

sis, when paired with intensive and appropriate inter-

vention, has the potential to positively impact the life of Conclusion

an individual with FASD.

Because at least 2% to 5% of the U.S. population suf-

Limitations fers from FASD [1], educators can make a big difference

in improving the identification of this often unrecog-

A key limitation of this study was the response rate.

nized disorder. In particular, school district administra-

Specifically, only 120 out of 325 (36.9%) potential par-

tors have the potential to provide critical and timely ad-

ticipants responded to the survey. Although the findings

vocacy for valuable training, assistance, and prevention

are still informative in an area with a dearth of research,

on behalf of students with FASD. However, limitations in

this response rate could limit how well these findings

knowledge in the area of FASD make such advocacy un-

generalize beyond this study. Further, this study only

likely. These areas are critical to address in educational

focused on superintendents in Minnesota. It is unclear

institutions as knowledge of the disorder is essential in

how these findings might generalize to other states with

taking the first steps to preventing the short- and long-

more diverse populations or where FASD trainings may

term consequences of FASD.

or may not be commonplace. Finally, this study only sur-

veyed superintendents. The inclusion of other education As highlighted by the findings of this survey, many

professionals such as teachers could alter findings. This superintendents lack a firm grasp on the educational

is important as teachers are more likely to have pro- and developmental impairments of students with FASD.

longed interactions with students than administrators. Although school district superintendents acknowledged

Nonetheless, these findings are an important first step that there are educational developmental impairments

in better understanding the familiarity of education pro- in school age children with FASD, very few could recall

fessionals with FASD. In turn, these findings emphasize key pieces of knowledge relevant to FASD. This includes

the importance for future research on a grander scale. the screening and assessment, clinical background,

treatment, and legal and policy issues of FASD. For ex-

Suggestions for future research ample, only about 30% of respondents recognized that

the vast majority of students with FASD lack physical

The current study demonstrates the potential for ex-

indicators of the disorder. To help improve short- and

pansion in several ways. First, this study should be repli-

long-term outcomes for students with FASD, there is a

cated in more diverse samples. Foremost, replicating this

need for advanced FASD training for educational pro-

study in a national sample could be helpful in understand-

fessionals.

ing how generalizable the findings are to other regions and

cultures. Further, surveying other professionals beyond Superintendents are an important target as these

superintendents could prove fruitful. Specifically, survey- professionals are likely to come into contact with stu-

ing other education professionals (e.g., principals, special dents with FASD due to the disorders educational and

education directors, school counselors, and teachers), behavioral impacts. These impairments may necessitate

mental health (e.g., school social workers and school psy- removal from classroom settings and require consider-

chologists), and criminal justice (e.g., school resource of- ation of more severe penalties such as long-term sus-

ficers) may provide previously undiscovered insights into pension and expulsion. If superintendents were more

the understanding of FASD. For example, school resource familiar with FASD, these important decision points

officers could help illuminate the initial criminal justice could serve as an opportunity for advocacy. For exam-

system contacts of adolescents with FASD. Alternative- ple, referrals for assessment and the development of

ly, applying the survey to caregivers, immediate family case management plans could prevent permanent re-

members, relatives, and the individuals themselves also moval from school or criminal justice involvement. To

may yield interesting results. Second, expansion of these address current shortcomings in the field, research is

surveys to gather information on different educational ap- needed to explore everything from how well educators

proaches and techniques used in this population could be and other professionals understand FASD to identifying

Brown et al. Int J Neurol Neurother 2017, 4:068 Page 7 of 8

DOI: 10.23937/2378-3001/1410068 ISSN: 2378-3001

ways to improve the screening and assessment of FASD Shaping the future for children with foetal alcohol spectrum

in education settings. If improvements are not made, disorders. Support for Learning 25: 139-145.

trouble in school settings experienced by students with 14. Streissguth AP, Randels SP, Smith DF (1991) A test-retest

FASD may increase the likelihood of worse outcomes in- study of intelligence in patients with fetal alcohol syndrome:

implications for care. Journal of the American Academy of

cluding involvement in the juvenile and adult criminal Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 30: 584-587.

justice systems.

15. Streissguth AP, Barr HM, Kogan J, Bookstein FL (1996)

References Understanding the occurrence of secondary disabilities in

clients with fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects.

1. May PA, Gossage JP, Kalberg WO, Robinson LK, Buckley D, Final report to the Centers for Disease Control and Preven-

et al. (2009) Prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of tion (CDC), Seattle, University of Washington, WA.

FASD from various research methods with an emphasis on

recent in-school studies. Dev Disabil Res Rev 15: 176-192. 16. Famy C, Streissguth AP, Unis AS (1998) Mental illness in

adults with fetal alcohol syndrome or fetal alcohol effects.

2. Clarke ME, Gibbard WB (2003) Overview of fetal alcohol American Journal of Psychiatry 155: 552-554.

spectrum disorders for mental health professionals. Can

Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev 12: 57-63. 17. Green CR, Mihic AM, Nikkel SM, Stade BC, Rasmussen C,

et al. (2009) Executive function deficits in children with fe-

3. Fast DK, Conry J (2009) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders tal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) measured using the

and the criminal justice system. Dev Disabil Res Rev 15: Cambridge Neuropsychological Tests Automated Battery

250-257. (CANTAB). J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50: 688-697.

4. Norman AL, OBrien JW, Spadoni AD, Tapert SF, Jones 18. Hon Susan Shepard Carlson, Hon Susan Shepard Carlson

KL, et al. (2013) A functional magnetic resonance imaging (2011) A judicial perspective on issues impacting the trial

study of spatial working memory in children with prenatal courts related to Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. The

alcohol exposure: contribution of familial history of alcohol Journal of Psychiatry & Law 39: 73-119.

use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37: 132-140.

19. Edmonds K, Crichton S (2008) Finding ways to teach stu-

5. Nunez CC, Roussotte F, Sowell ER (2011) Focus on: dents with FASD, a research study. International Journal Of

structural and functional brain abnormalities in fetal alcohol Special Education 23: 54-73.

spectrum disorders. Alcohol Res Health 34: 121-131.

20. Susan Ryan, Dianne L Ferguson (2006) On, yet under the

6. Rasmussen C (2005) Executive functioning and working radar: Students with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorder. Ex-

memory in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp ceptional Children 72: 363-379.

Res 29: 1359-1367.

21. Thiel K, Baladerian N, Boyce K, Cantos O, Davis L, et al.

7. Kalberg WO, Buckley D (2007) FASD: What types of inter- (2010) Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders and victimization:

vention and rehabilitation are useful? Neurosci Biobehav Implications for families, educators, social services, law en-

Rev 31: 278-285. forcement, and the judicial system. Journal of Psychiatry &

8. Streissguth AP, Barr HM, Sampson PD, Bookstein FL Law 39: 121-157.

(1994) Prenatal alcohol and off spring development: the 22. Gunn J (2013) Meeting the needs of children with foetal al-

first fourteen years. Drug Alcohol Depend 36: 89-99. cohol spectrum disorder through research based interven-

9. Wheeler SM, Stevens SA, Sheard ED, Rovet JF (2012) Fa- tions. New Zealand Journal of Teachers Work 10: 148-168.

cial memory deficits in children with fetal alcohol spectrum 23. Olson H, Oti R, Gelo J, Beck S (2009) Family matters: Fe-

disorders. Child Neuropsychol 18: 339-346. tal alcohol spectrum disorders and the family. Dev Disabil

10. Kodituwakku PW, Handmaker NS, Cutler SK, Weathersby Res Rev 15: 235-249.

EK, Handmaker SD (1995) Specific impairments in self-reg- 24. IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Win-

ulation in children exposed to alcohol prenatally. Alcohol dows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Alcoholism:

Clin Exp Res 19: 1558-1564. Clinical and Experimental Research 19: 1558-1564.

11. Bower E, Szajer J, Mattson SN, Riley EP, Murphy C (2013) 25. Murawski NJ, Moore EM, Thomas JD, Riley EP (2015) Ad-

Impaired odor identification in children with histories of vances in diagnosis and treatment of Fetal Alcohol Spec-

heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol 47: 275-278. trum Disorders: From Animal Models to Human Studies.

12. Mattson SN, Crocker N, Nguyen TT (2011) Fetal alcohol Alcohol Res 37: 97-108.

spectrum disorders: neuropsychological and behavioral 26. Spohr HL, Willms J, Steinhausen HC (1994) The fetal alcohol

features. Neuropsychol Rev 21: 81-101. syndrome in adolescence. Acta Paediatr Suppl 404: 19-26.

13. Carolyn Blackburn, Barry Carpenter, Jo Egerton (2010)

Brown et al. Int J Neurol Neurother 2017, 4:068 Page 8 of 8

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- News: Alcohol Warning Labels in IrelandDocument1 pageNews: Alcohol Warning Labels in IrelandfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Flyer For Book On FASD and American IndiansDocument1 pageFlyer For Book On FASD and American IndiansfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- FASD Awareness Month 2023 Proclamation MassachusettsDocument1 pageFASD Awareness Month 2023 Proclamation MassachusettsfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- SAFEST Choice Learning Collaborative: Recruiting Health CentersDocument1 pageSAFEST Choice Learning Collaborative: Recruiting Health CentersfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Are More Common Than We ThinkDocument4 pagesFetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Are More Common Than We ThinkfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Teleconference Training: FASD 101: Parent To Parent of NYSDocument1 pageTeleconference Training: FASD 101: Parent To Parent of NYSfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Indiana FASD Day Proclamation 2022Document1 pageIndiana FASD Day Proclamation 2022fasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- ECHO FASD Flier With Registration LinkDocument1 pageECHO FASD Flier With Registration LinkfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- ECHO FASD Information Flier 9.23.22Document1 pageECHO FASD Information Flier 9.23.22fasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Conversations About Alcohol Use Help Social Workers Assess, Reduce Clients' Risky DrinkingDocument2 pagesConversations About Alcohol Use Help Social Workers Assess, Reduce Clients' Risky DrinkingfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Proof Alliance Speakers BureauDocument1 pageProof Alliance Speakers BureaufasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Nurses and Midwives: Partnering To Prevent FASDsDocument3 pagesNurses and Midwives: Partnering To Prevent FASDsfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Rotary Club Members Bring Awareness of FASDDocument3 pagesRotary Club Members Bring Awareness of FASDfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestational Age and Birth Growth Parameters As Early Predictors of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum DisordersDocument15 pagesGestational Age and Birth Growth Parameters As Early Predictors of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum DisordersfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Drug and Alcohol Dependence: SciencedirectDocument15 pagesDrug and Alcohol Dependence: SciencedirectfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- David Peeples Joins Proof Alliance As Associate Director of ProgramsDocument1 pageDavid Peeples Joins Proof Alliance As Associate Director of ProgramsfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- NOFAS Enshrines Pip Williams in Tom and Linda Daschle Hall of FameDocument1 pageNOFAS Enshrines Pip Williams in Tom and Linda Daschle Hall of FamefasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Proof Alliance Partners With The Arc of North Carolina To Expand Programming To Reduce Prenatal Alcohol ExposureDocument1 pageProof Alliance Partners With The Arc of North Carolina To Expand Programming To Reduce Prenatal Alcohol ExposurefasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Individuals With FASD and The Courts: What Social Workers Need To KnowDocument3 pagesIndividuals With FASD and The Courts: What Social Workers Need To Knowfasdunited100% (5)

- Perceptions of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) at A Mental Health Outpatient Treatment Provider in MinnesotaDocument10 pagesPerceptions of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) at A Mental Health Outpatient Treatment Provider in MinnesotafasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Step Away App Fact Sheet 2020Document1 pageStep Away App Fact Sheet 2020fasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- FASD Support Group - UpdatedDocument1 pageFASD Support Group - UpdatedfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- FASD: What Alaskan Nurses Can DoDocument4 pagesFASD: What Alaskan Nurses Can DofasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- FASD and Sexually Inappropriate Behaviors: A Guide For Criminal Justice and Forensic Mental Health ProfessionalsDocument35 pagesFASD and Sexually Inappropriate Behaviors: A Guide For Criminal Justice and Forensic Mental Health ProfessionalsfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- UCLA Brain MRI Study of Children With FASDDocument1 pageUCLA Brain MRI Study of Children With FASDfasdunited100% (1)

- FASD: Thirty Reasons Why Early Identification MattersDocument4 pagesFASD: Thirty Reasons Why Early Identification MattersfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethical Aspects of Diagnosis and Interventions For Children With Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder FASD and Their FamiliesDocument7 pagesEthical Aspects of Diagnosis and Interventions For Children With Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder FASD and Their FamiliesfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- A Review of The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), AUDIT-C, and USAUDIT For Screening in The United States: Past Issues and Future DirectionsDocument10 pagesA Review of The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), AUDIT-C, and USAUDIT For Screening in The United States: Past Issues and Future DirectionsfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- FASD Training in Dallas June 8, 2018Document1 pageFASD Training in Dallas June 8, 2018fasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Biomarkers Utilitarian ApproachDocument8 pagesBiomarkers Utilitarian ApproachfasdunitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Application of Discovery Learning To Train The Creative Thinking Skills of Elementary School StudentDocument8 pagesApplication of Discovery Learning To Train The Creative Thinking Skills of Elementary School StudentInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Louis Review Center Post Test Principles of TeachingDocument8 pagesSt. Louis Review Center Post Test Principles of TeachingGibriel SllerPas encore d'évaluation

- True 3 Little Pigs LPDocument4 pagesTrue 3 Little Pigs LPapi-384512330Pas encore d'évaluation

- Midterm Reflection FinalDocument4 pagesMidterm Reflection Finaljthom301Pas encore d'évaluation

- Summer Reading CampDocument5 pagesSummer Reading CampJeyson B. BaliosPas encore d'évaluation

- The Virtual Professor: A New Model in Higher Education: Randall Valentine, Ph.D. Robert Bennett, PH.DDocument5 pagesThe Virtual Professor: A New Model in Higher Education: Randall Valentine, Ph.D. Robert Bennett, PH.DStephanie RiadyPas encore d'évaluation

- Southern Luzon State University: (Indicate The Daily Routine(s) )Document2 pagesSouthern Luzon State University: (Indicate The Daily Routine(s) )Banjo De los SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Reading and Studying the Bible on Biblical KnowledgeDocument4 pagesThe Impact of Reading and Studying the Bible on Biblical KnowledgeRuth PerezPas encore d'évaluation

- CulturediagramDocument2 pagesCulturediagramapi-239582398Pas encore d'évaluation

- Information Resource ManagementDocument2 pagesInformation Resource ManagementMansour BalindongPas encore d'évaluation

- SWAPNA Teacher ResumeDocument3 pagesSWAPNA Teacher ResumecswapnarekhaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Kinds of Training Provided at OrkinDocument3 pagesThe Kinds of Training Provided at OrkinasifibaPas encore d'évaluation

- IAS Topper Profile: Gaurav Agrawal shares preparation strategyDocument46 pagesIAS Topper Profile: Gaurav Agrawal shares preparation strategyOm Singh Inda100% (1)

- Introducción de Kahlbaum Por HeckerDocument5 pagesIntroducción de Kahlbaum Por HeckerkarlunchoPas encore d'évaluation

- Graphic Organizer Concept AttainmentDocument1 pageGraphic Organizer Concept Attainmentapi-272175470Pas encore d'évaluation

- Getting To Know SomeoneDocument4 pagesGetting To Know SomeonePatricia PerezPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Historical and Societal Influences On Curriculum 1 1Document42 pages2 Historical and Societal Influences On Curriculum 1 1Ogie Achilles D TestaPas encore d'évaluation

- Maligaya Elementary School: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region III Division of City SchoolsDocument2 pagesMaligaya Elementary School: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region III Division of City SchoolsMarilyn Dela Cruz SicatPas encore d'évaluation

- Ead 536 Induction Plans For Beginning TeachersDocument7 pagesEad 536 Induction Plans For Beginning Teachersapi-337555351100% (2)

- Chris Peck CV Hard Copy VersionDocument6 pagesChris Peck CV Hard Copy VersionChris PeckPas encore d'évaluation

- MSc Biophysics Ulm University - Interdisciplinary Life Sciences ProgramDocument2 pagesMSc Biophysics Ulm University - Interdisciplinary Life Sciences ProgramWa RioPas encore d'évaluation

- 5100 CourseworkDocument59 pages5100 CourseworkSchmaboePas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Lesson Log: Subject:21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World DateDocument3 pagesDaily Lesson Log: Subject:21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World DateAseret MihoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ah19940401 V16 02Document48 pagesAh19940401 V16 02Brendan Paul ValiantPas encore d'évaluation

- NLP Leadership SkillsDocument12 pagesNLP Leadership SkillsCassandra ChanPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Design EssayDocument8 pagesCurriculum Design EssayGrey ResterPas encore d'évaluation

- Differentiation Math Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesDifferentiation Math Lesson Planapi-250343290Pas encore d'évaluation

- CBSE JEE(Main) 2015 admit card for Jose Daniel GumpulaDocument1 pageCBSE JEE(Main) 2015 admit card for Jose Daniel GumpulaSuman BabuPas encore d'évaluation

- Delay SpeechDocument8 pagesDelay Speechshrt gtPas encore d'évaluation