Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Guia para El TDAH

Transféré par

EstebanGiraTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Guia para El TDAH

Transféré par

EstebanGiraDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

PRIMER

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Stephen V.Faraone1,2, Philip Asherson3, Tobias Banaschewski4, Joseph Biederman5,

JanK.Buitelaar6, Josep Antoni Ramos-Quiroga79, Luis Augusto Rohde10,11,

EdmundJ.S.Sonuga-Barke12,13, Rosemary Tannock14,15 and Barbara Franke16

Abstract | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a persistent neurodevelopmental disorder

that affects 5% of children and adolescents and 2.5% of adults worldwide. Throughout an individuals

lifetime, ADHD can increase the risk of other psychiatric disorders, educational and occupational failure,

accidents, criminality, social disability and addictions. No single risk factor is necessary or sufficient to cause

ADHD. In most cases ADHD arises from several genetic and environmental risk factors that each have a

small individual effect and act together to increase susceptibility. The multifactorial causation of ADHD is

consistent with the heterogeneity of the disorder, which is shown by its extensive psychiatric co-morbidity,

its multiple domains of neurocognitive impairment and the wide range of structural and functional brain

anomalies associated with it. The diagnosis of ADHD is reliable and valid when evaluated with standard

criteria for psychiatric disorders. Rating scales and clinical interviews facilitate diagnosis and aid screening.

The expression of symptoms varies as a function of patient developmental stage and social and academic

contexts. Although there are no curative treatments for ADHD, evidenced-based treatments can markedly

reduce its symptoms and associated impairments. For example, medications are efficacious and normally

well tolerated, and various non-pharmacological approaches are also valuable. Ongoing clinical and

neurobiological research holds the promise of advancing diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to ADHD.

For an illustrated summary of this Primer, visit: http://go.nature.com/J6jiwl

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; also associated with ADHD. These studies have created relia-

known as hyperkinetic disorder) is a common dis- ble and valid measurement tools for screening, diagnosis

order characterized by inattention or hyperactivity and monitoring of treatment. Likewise, rigorous clinical

impulsivity, or both. The evidence base for the diagnosis trials have documented the safety and efficacy of ADHD

and treatment of ADHD has been growing exponentially treatment, and it is now clear which ADHD treatments

since the syndrome was first described by a German work, which do not and which require further study. In

physician in 1775 (REF.1) (FIG.1). In 1937, the efficacy this Primer, we discuss the evidence base that has created

of amphetamine use to reduce symptom severity was a firm foundation for future work to further clarify the

serendipitously discovered. In the 1940s, the brainwas aetiology and pathophysiology of ADHD and to advance

implicated as the source of ADHD-like symptoms, which diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to this disorder.

were described as minimal brain damage in the wake of

Correspondence to S.V.F.

e-mail: sfaraone@

an encephalitis epidemic. In 1980, the third edition of Epidemiology

childpsychresearch.org the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Age-dependent prevalence of ADHD

Departments of Psychiatry (DSM) created the first reliable operational diagnostic ADHD is a common disorder among young people

and of Neuroscience and criteria for the disorder. These criteria initiated many worldwide. In 2007, a meta-analysis of more than 100

Physiology, State University

programmes of research that ultimately led the scien- studies estimated the worldwide prevalence of ADHD in

of New York (SUNY) Upstate

Medical University, Syracuse,

tific community to view ADHD as a seriously impair- children and adolescents to be 5.3% (95% CI: 5.015.56)2.

New York 13210, USA; ing, often persistent neurobiological disorder of high Three methodological factors explained this variabil-

K.G.Jebsen Centre for prevalence that is caused by a complex interplay between ity among studies: the choice of diagnostic criteria, the

Neuropsychiatric Disorders, genetic and environmental risk factors. These risk fac- source of information used and the inclusion of a require-

Department of Biomedicine,

University of Bergen,

tors affect the structural and functional capacity of brain ment for functional impairment as well as symptoms for

5020Bergen, Norway. networks and lead to ADHD symptoms, neurocognitive diagnosis. After adjusting for these factors, a subsequent

deficits and a wide range of functionalimpairments. meta-analysis concluded that the prevalence of ADHD

Article number: 15020

doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.20

We now have many large and well-designed epi does not significantly differ between countries in Europe,

Published online demiological, clinical and longitudinal studies that have Asia, Africa and the Americas, as well as in Australia3.

6 August 2015 clarified the features, co-morbidities and impairments Although other meta-analyses have found either lower or

NATURE REVIEWS | DISEASE PRIMERS VOLUME 1 | 2015 | 1

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

Author addresses

symptoms; and third, enabling ADHD to be diagnosed

in the presence of an autism spectrum disorder. The

1

Departments of Psychiatry and of Neuroscience and Physiology, State University third change is consistent with the reconceptualization

ofNewYork (SUNY) Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York 13210, USA. of ADHD in DSM5 as a neurodevelopmental disorder

2

K.G.Jebsen Centre for Psychiatric Disorders, Department of Biomedicine, rather than a disruptive behavioural disorder. Overall,

UniversityofBergen, 5020 Bergen, Norway.

these new criteria have yielded an increase in ADHD

3

Social Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry Psychology

andNeuroscience, Kings College London, London, UK.

prevalence, which is insubstantial for children but is likely

4

Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Central Institute of to have had a more considerable effect on diagnosis rates

Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany. in adults13,14.

5

Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital,

Pediatric Psychopharmacology Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Sociodemographic factors

Massachusetts, USA. Alongside age, other factors such as sex, ethnicity and

6

Radboud University Medical Center, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and socioeconomic status are also important when consider

Behaviour, Department of Cognitive Neuroscience and Karakter Child and Adolescent ing the prevalence of ADHD. In children andadolescents,

Psychiatry University Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. ADHD predominantly affects males and exhibits a male-

7

ADHD Program, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital Universitari Vall dHebron,

to-female sex ratio of 4:1 in clinical studies and 2.4:1 in

Barcelona, Spain.

8

Biomedical Network Research Centre on Mental Health (CIBERSAM), Barcelona, Spain.

population studies2. In adulthood, this sex discrepancy

9

Department of Psychiatry and Legal Medicine, Universitat Autnoma de Barcelona, almost disappears14, possibly owing to referral biases

Barcelona, Spain. among treatment-seeking patients or to sexspecific

10

ADHD Outpatient Program, Hospital de Clinicas de Porto Alegre, Department of effects of ADHD over the course of thedisorder.

Psychiatry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. Larsson and colleagues 15 found that low family

11

National Institute of Developmental Psychiatry for Children and Adolescents, income predicted an increased likelihood of ADHD in

SaoPaulo, Brazil. a Swedish population-based cohort study of 811,803

12

Department of Psychology, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. individuals. However, this finding does not necessar-

13

Department of Experimental Clinical and Health Psychology, Ghent University, Ghent, ily support the conclusion that socioeconomic status

Belgium.

increases the risk of ADHD because the disorder

14

Neuroscience and Mental Health Research Program, Research Institute of The Hospital

for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada.

runs in families and leads to educational and occupa-

15

Department of Applied Psychology and Human Development, Ontario Institute for tional underattainment. Underemployment could in

Studies in Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. turn lead to the over-representation of socioeconomic

16

Radboud University Medical Center, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and disadvantage among families affected by ADHD16.

Behaviour, Departments of Human Genetics and Psychiatry, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Finally, although the true prevalence of ADHD does

not vary with ethnicity, some studies have inconsistently

associated ethnicity with ADHD owing to referral pat-

higher prevalence rates, these presented important limita- terns and barriers to care that disproportionately affect

tions, such as the exclusive use of DSM criteria to diagnose particular ethnic groups1719.

ADHD and the use of simulated prevalence rates4,5. In

addition, there is no evidence, worldwide, of an increase Mechanisms/pathophysiology

in the real prevalence of ADHD over the past three Genes and environment

decades3. Despite the fact that both overdiagnosis and Genetic epidemiology. ADHD runs in families, with

underdiagnosis are common concerns in medicine, the parents and siblings of patients with ADHD show-

common public perception that ADHD is overdiagnosed ing between a fivefold and tenfold increased risk of

in the United States might not be warranted6. developing the disorder compared with the general

ADHD also affects adults. Although the majority population20,21. Twin studies show that ADHD has a

of children with ADHD will not continue to meet the heritability of 7080% in both children and adults2225,

full set of criteria for ADHD as adults, the persistence of with little or no evidence that the effects of environ

either functional impairment 7 or subthreshold (three or mental risk factors shared by siblings substantially influ-

fewer) impairing symptoms into adulthood is high8. For ence aetiology 26. Environmental risk factors play their

instance, on the basis of a meta-analysis of six studies, greatest part in the non-shared familial environment

Simon and colleagues9 found the pooled prevalence of and/or act through interactions with genes and DNA

ADHD to be 2.5% (95% CI: 2.13.1) in adults. In addi- variants that regulate gene expression such as those

tion, studies in older adults have found prevalence rates in promoters, untranslated regions of genes or loci that

in the same range10,11, and prospective longitudinal stud- encodemicroRNAs.

ies support the notion that approximately two-thirds of Although ADHD is a categorical diagnosis, results

youths with ADHD retain impairing symptoms of the from twin studies suggest that it is the extreme and

disorder in adulthood7 (FIG.2). impairing tail of one or more heritable quantitative traits27.

Recent alterations to diagnostic criteria have had an The disorder is influenced by both stable genetic factors

impact on ADHD prevalence measures in both young and those that emerge at different developmental stages

and adult populations. In 2013, DSM5 (REF.12) included from childhood through to adulthood28. Thus, genes con-

three important changes: first, increasing the age of onset tribute to the onset, persistence and remission of ADHD,

from 7years to 12years; second, decreasing the symptom presumably through stable neurobiological deficits as

threshold for patients 17years of age from six to five well as maturational or compensatory processes that

2 | 2015 | VOLUME 1 www.nature.com/nrdp

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

Weikard describes ADHD syndrome in a German textbook DSM-II describes hyperkinetic reaction Omega-3 is a weak but eective

treatment

Douglas neurocognitive model of ADHD

Homan cartoons of Still describes DSM-5 extends age of onset

Fidgeting Philip and defect of moral to 12 years and adjusts criteria

control in ADHD-like symptoms Twin studies for adults

Johnny Head-in-the-Air

The Lancet described as minimal document high

brain damage heritability CBT for adult ADHD

Bourneville, Boulanger, Paul-Boncour US FDA approves DSM-III Rare genomic insertions and

and Philippe describe ADHD symptoms methylphenidate operationalizes deletions discovered

as mental instability in French medical for depression diagnostic

and educational literature and narcolepsy criteria Molecular polygenic

background conrmed

1775 1798 1845 1887 1901 1910 1930s 1940s 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1985 1990s 1995 2000s 2010s

Sagvolden describes an ADHD rat model

Bradley shows that benzedrine

reduces hyperactivity Similar correlates of ADHD found in boys and girls CDC describes

Crichton describes ADHD as a

ADHD syndrome in KramerPollnow syndrome Neuroimaging documents structural and serious public

a Scottish textbook discovered Parent training functional brain anomalies health problem

treatments

DSM-IV renes criteria Long-acting

Methylphenidate stimulants

Prediagnostic era ADHD in adults recognized as a valid disorder developed

indicated for

Minimal brain dysfunction era behavioural

Attention-decit disorder era disorders Co-morbidity with anxiety, mood or autism spectrum Non-stimulants

ADHD era in children disorders and executive dysfunction conrmed approved

Nature Reviews | Disease Primers

Figure 1 | The history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

syndromes have been described in the medical literature since the eighteenth century, but the growth of systematic

research required the development of operational diagnostic criteria in the late twentieth century. This schematic

outlines selected important developments in the history of ADHD research. CBT, cognitivebehavioural therapy;

CDC,Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

influence development. The inattention and hyperactiv- and twin studies that found significant coaggregation

ity or impulsivity that characterize ADHD are separate of ADHD with depression37, conduct problems39 and

domains of psychopathology, with a genetic correlation schizophrenia40. Furthermore, combined GWAS of

of around 0.6, reflecting substantial geneticoverlap but ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, depression, bipolar

also genetic influences that are domain specific29. Shared disorder and schizophrenia identified four genome-wide

genetic factors also account for the cooccurrence of significant loci shared by these disorders37.

ADHD with emotional dysregulation an independ- In addition to the common-variant studies, rare

ent source of impairment in ADHD30,31. Family and twin (prevalence of <1%) genomic insertions and deletions

studies have also demonstrated that genetic influences known as copy number variants (CNVs) have a role

are shared between ADHD and a wide range of other in ADHD41,42. One study found that 15.6% of patients

neurodevelopmental and psychopathological traits and with ADHD carry large CNVs of >500,000 base pairs

disorders, including conduct disorder and problems32, in length compared with 7.5% of individuals without

cognitive performance33, autism spectrum disorders34 the disorder. The rate of large CNV carriage was even

and mood disorders35,36. higher (42.4%) in those with both ADHD and an IQ

below 705 (which, along with poor adaptive function-

Molecular genetics. On the basis of data from genome- ing, defines intellectual disability)42. These findings have

wide association studies (GWAS), approximately 40% of been replicated43, and together these studies implicate

the heritability of ADHD can be attributed to numer- genes at 16p13.11 along with the 15q1115q13 region in

ous common genetic variants37. In polygenic risk score ADHD. The 15q1115q13 region contains the gene that

analysis, the genetic signals attributed to common vari- encodes the nicotinic 7 acetylcholine receptor subunit,

ants derived from a discovery sample are used to predict which participates in neuronal and nicotinic signalling

phenotypic effects in a second sample. The polygenic risk pathways. Finally, ADHD-associated CNVs also span

for clinically diagnosed ADHD predicts ADHD symp- several glutamate receptor genes, which are essential

toms in the population more broadly 38, confirming the for neuronal glutamatergic transmission44, and the gene

conclusion from twin studies that the genes determining encoding neuropeptide Y, which is involved in signal-

the diagnosis of ADHD also regulate the expression of ling in the brain and autonomic nervous system45. CNVs

subclinical levels of ADHD symptoms. Inaddition, these associated with ADHD also occur in schizophrenia

analyses have confirmed earlier evidence from family andautism42.

NATURE REVIEWS | DISEASE PRIMERS VOLUME 1 | 2015 | 3

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

100 evoke hostile styles of parenting, and genes linked to

ADHD might explain the association of parental vari-

ables, such as maternal smoking during pregnancy,

75 with offspring who have ADHD51,52. One notable study

71% investigated maternal hostility while controlling for

Persistence (%)

65% genetic effects by studying children adopted at birth

50 and children conceived through in vitro fertiliza-

tionand their genetically unrelated rearing mothers53.

The study found a role for genetically influenced early

25 Functional impairment child behaviour on the hostility of biologically unrelated

Impairing symptoms 15% mothers, which in turn was a predictor of subsequent

Full diagnostic criteria ADHD symptoms developed by the children. Another

0 study followed Romanian adoptees who had experi-

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 enced severe early maternal deprivation in orphanages

Mean age at follow-up (years) before adoption. It showed a dose-dependent relation-

Figure 2 | The age-dependent decline and persistence of attention-deficit/ ship between length of deprivation and risk of develop-

Nature Reviews | Disease Primers

hyperactivity disorder throughout the lifetime. Followup studies have assessed ing ADHD-like symptoms54. Other environmental risk

children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) at multiple time points factors that have been associated with ADHD include

after their initial diagnosis. Although they document an age-dependent decline in ADHD prenatal and perinatal factors, such as maternal smok-

symptoms, ADHD is also a highly persistent disorder when defined by the persistence of ing and alcohol use, low birth weight, premature birth

functional impairment7 or the persistence of subthreshold (three or fewer) impairing

and exposure to environmental toxins, such as organo-

symptoms8. By contrast, many patients remit full diagnostic criteria7.

phosphate pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls, zinc

and lead55,56. Animal models have also contributed

Although GWAS that investigated common genetic much to the study of environmental risk factors5759.

variants (FIG.3) have not identified specific ADHD genes Similar to genetic risk factors, the effects of any one

at genome-wide levels of significance46, intriguing results environmental risk factor are small and could reflect

have emerged from meta-analyses of studies of candi- either small effects in many cases or larger effects in a

date genes involved in the monoamine neurotransmit- few cases. Furthermore, rather than being specific to

ter systems47. These systems had been implicated in the ADHD, these environmental risk factors are associated

pathophysiology of ADHD by the mechanisms of action with several psychiatric disorders29.

of drugs used in clinical management. Methylphenidate In addition to the main effects of the environment,

and amphetamine target the sodium-dependent dopa- the high heritability of ADHD suggests that gene

mine transporter (encoded by SLC6A3), atomoxetine environment (GE) interactions might be the main

targets the sodium-dependent noradrenaline trans- mechanism by which environmental risk factors increase

porter, and both extended-release guanfacine and the risk of ADHD. For example, a variant of 5HTTLPR

extended-release clonidine target the 2A-adrenergic a polymorphic region located in the promoter of SLC6A4

receptor. Within the monoamine systems, the strongest is involved in the hyperactivity and impulsivity dimen-

evidence of ADHD association is for variants in the genes sions of ADHD in interaction with stress60. Although

encoding the D4 and D1B dopamine receptors47. The some early studies identified other GE effects, none

association of the SLC6A3 gene variant is equivocal47, has been reliably reproduced. Future success in this area

possibly owing to age-related effects48. Other genes that requires the use of large data sets, such as those emerg-

show possible associations with ADHD include SLC6A4 ing from the use of national databases in Denmark and

(which encodes the sodium-dependent serotonin trans- Sweden, which can combine large-scale genetic studies

porter), HTR1B (which encodes 5hydroxytryptamine with recorded data on exposure to environmentalrisks.

receptor 1B (also known as serotonin receptor 1B)) and Another approach to identify environmental risk fac-

SNAP25 (which encodes synaptosomal-associated pro- tors in ADHD is to focus on the detection of epigenetic

tein 25)47. Owing to methodological issues, a cautious changes, such as DNA methylation, which are revers-

approach must be taken to the interpretation of candi ible changes in genomic function that are independent

date gene studies. Nevertheless, the role of the dopa- of DNA sequence. Epigenetics provides a mechanism

mine, noradrenaline, serotonin and neurite outgrowth by which environmental risk factors alter gene func-

systems is supported by genome-wide association study- tion. However, as epigenetic changes are highly tissue

based gene-set analyses reporting that, as a group, genes specific, they are difficult to study in ADHD because of

regulating these systems were associated with ADHD limited access to brain tissue. Studies must, therefore,

and hyperactivity or impulsivity 46,49,50. rely on peripheral tissues such as blood, the epigenetic

profile of which partly overlaps with that of brain tis-

Environmental risk factors. Identifying environmental sue. Environmental toxins and stress can all induce epi

causes of ADHD is difficult because environmen- genetic changes, thus the identification of genes that

talassociations might arise from other sources, such show epigenetic changes linked to ADHD, or in response

as from child or parental behaviours that shape the to environmental risk factors, might in the future pro-

environment, or they might reflect unmeasured third vide new insights into the mechanisms involved in the

variables. For example, children with ADHD might pathogenesis ofADHD61.

4 | 2015 | VOLUME 1 www.nature.com/nrdp

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

Brain mechanisms anticipation of reward than in controls75. ADHD is also

Cognition. ADHD is characterized by decits in multi- associated with hyperactivation in somatomotor and vis-

ple, relatively independent, cognitive domains. Executive ual systems74, which possibly compensates for impaired

functioning deficits are seen in visuospatial and verbal functioning of the prefrontal and anterior cingulate cor-

working memory, inhibitory control, vigilance and tices76. A single dose of methylphenidate (a stimulant)

planning 62,63. Studies of reward dysregulation show that markedly enhances activation in the inferior frontal cor-

patients with ADHD make suboptimal decisions64, pre- tex and insula bilaterally which are key areas of cogni-

fer immediate rather than delayed rewards65 and over- tive control during inhibition and time discrimination

estimate the magnitude of proximal relative to distal but does not affect working memory networks77. By con-

rewards66. Other domains impaired in ADHD include trast, long-term treatment with stimulants is associated

temporal information processing and timing 67; speech with normal activation in the right caudate nucleus dur-

and language68; memory span, processing speed and ing the performance of attention tasks78. Resting-state

response time variability 69; arousal and activation70; MRI studies have shown that ADHD is associated with

and motor control71. Although most patients with less-pronounced or absent anti-correlations between the

ADHD show deficits in one or two cognitive domains, default-mode network (DMN) and the cognitive control

some have no deficits and very few show decits in all network, lower connectivity within the DMN itself and

domains72. In addition, across the lifespan of patients lower connectivity within the cognitive and motivational

with ADHD, deficits in cognitive control, reward sensi loops of the frontostriatal circuits79.

tivity and timing have been shown to be independent Along with functional changes, a range of struc-

of one another 73, and it is currently unclear whether tural brain alterations are also associated with ADHD.

cognitive deficits cause ADHD symptoms and drivethe For example, ADHD is associated with a 35% smaller

development of the clinical phenotype 72 or reflect total brain size than unaffected controls80,81 that can be

thepleiotropic outcomes of risk factors. attributed to a reduction of grey matter 82. Consistent

with genetic data that support a model of ADHD as the

Structural and functional brain imaging. Several brain extreme of a population trait, total brain volume cor-

regions and neural pathways have been implicated relates negatively with ADHD symptoms in the general

inADHD (FIG.4). Functional MRI studies in patients with population83. In patients with ADHD, meta-analyses

ADHD that used inhibitory control, working memory have documented smaller volumes across several brain

and attentional tasks have shown underactivation of fron- regions, most consistently in the right globus pallidus,

tostriatal, frontoparietal and ventral attention networks74. right putamen, caudate nucleus and cerebellum84,85.

The frontoparietal network mediates goal-directed Inaddition, a meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging

executive processes, whereas the ventral attention net- studies showed widespread alterations in white matter

work facilitates reorientation of attention towards salient integrity, especially in the right anterior corona radiata,

and behaviourally relevant external stimuli. In reward- right forceps minor, bilateral internal capsule and left

processing paradigms, most studies report lower activa- cerebellum86. Both structural and functional imaging

tion of the ventral striatum of patients with ADHD in findings are very variable across studies, suggesting that

the neural underpinnings of ADHD are heterogeneous,

which is consistent with studies of cognition.

22q11.2 deletion syndrome 16p13.11 Monoamine Just as the prevalence of ADHD is associated with

15q1115q11 13 region containing systems

Jacobsen syndrome genes age (FIG.2), so too are many changes in the brains of

(deletions of the end of 11q) nicotinic 7 acetylcholine

receptor subunit gene Neurite patients with ADHD7. Some brain volumetric alterations

Turner syndrome (X0) outgrowth

Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) Rare point mutations expected

genes observed in childhood normalize with age82,85, whereas

from sequencing studies

other measures remain fixed. For example, a longitudi-

nal MRI study found lower basal ganglion volumes and

High

Rare reduced dorsal surface area in adolescents with ADHD

chromosomal compared with controls, and this difference did not

anomalies

change as patients aged87. Furthermore, for ventral striatal

surfaces, control individuals showed surface area expan-

Rare and low

Eect size

sion with age, whereas patients with ADHD experienced

frequency copy

number variants a progressive contraction of the surface area. The as-yet-

unknown process underlying this contraction might

explain abnormal processing of reward in ADHD87.

Common variants

explain ~40% ADHD is also associated with delayed maturation of the

of heritability cerebral cortex. In one study, the age of attaining peak

cortical thickness was 10.5years for patients with ADHD

Low

Very rare Rare Low Common

and 7.5years for unaffected individuals; this delay was

Allele frequency most prominent in the prefrontal regions that are impor-

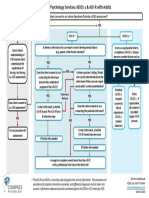

Figure 3 | Genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Common variants tant for executive functioning, attention and motor plan-

Nature Reviews | Diseasedisorder

explain approximately 40% of the heritability of attention-deficit/hyperactivity Primers ning 88. The development of cortical surface area was

but, compared with rarer causes, individual common variants have much smaller effects also shown to be delayed in patients with ADHD, but

on the expression of the disorder. ADHD was not associated with altered developmental

NATURE REVIEWS | DISEASE PRIMERS VOLUME 1 | 2015 | 5

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

a Dorsolateral Parietal b Ventral anterior Dorsal anterior c d

Nigrostriatal

prefrontal cortex cortex cingulate cortex cingulate cortex Mesocortical Locus Cortex Thalamus

Caudate coeruleus

nucleus

Dorsal

Mesolimbic anterior

Nucleus

Ventromedial accumbens Substantia nigra cingulate Basal

prefrontal tegmentum cortex ganglia

Putamen

cortex Noradrenergic Executive control Pons

Amygdala Cerebellum Dopaminergic Corticocerebellar

e f g

Orbitofrontal Frontal Medial view Lateral view Lateral

cortex cortex parietal

cortex

Medial Medial

Ventromedial prefrontal prefrontal

prefrontal Ventral cortex Posterior cortex

cortex striatum cingulate Medial

cortex temporal lobe

Figure 4 | Brain mechanisms in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. a | The cortical regions

Nature (lateral

Reviews view) ofPrimers

| Disease the

brain have a role in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is linked to working

memory, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex to complex decision making and strategic planning, and the parietal cortex

toorientation of attention. b | ADHD involves the subcortical structures (medial view) of the brain. The ventral anterior

cingulate cortex and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex subserve affective and cognitive components of executive

control. Together with the basal ganglia (comprising the nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus and putamen), they form

the frontostriatal circuit. Neuroimaging studies show structural and functional abnormalities in all of these structures in

patients with ADHD, extending into the amygdala and cerebellum. c | Neurotransmitter circuits in the brain are involved in

ADHD. The dopamine system plays an important part in planning and initiation of motor responses, activation, switching,

reaction to novelty and processing of reward. The noradrenergic system influences arousal modulation, signal-to-noise

ratios in cortical areas, state-dependent cognitive processes and cognitive preparation of urgent stimuli. d| Executive

control networks are affected in patients with ADHD. The executive control and corticocerebellar networks coordinate

executive functioning, that is, planning, goal-directed behaviour, inhibition, working memory and the flexible adaptation

to context. These networks are underactivated and have lower internal functional connectivity in individuals with ADHD

compared with individuals without the disorder. e | ADHD involves the reward network. The ventromedial prefrontal

cortex, orbitofrontal cortex and ventral striatum are at the centre of the brain network that responds to anticipation and

receipt of reward. Other structures involved are the thalamus, the amygdala and the cell bodies of dopaminergic neurons

in the substantia nigra, which, as indicated by the arrows, interact in a complex manner. Behavioural and neural responses

to reward are abnormal in ADHD. f | The alerting network is impaired in ADHD. The frontal and parietal cortical areas and

the thalamus intensively interact in the alerting network (indicated by the arrows), which supports attentional functioning

and is weaker in individuals with ADHD than in controls. g | ADHD involves the default-mode network (DMN). The DMN

consists of the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex (medial view) as well as the lateral parietal

cortex and the medial temporal lobe (lateral view). DMN fluctuations are 180degrees out of phase with fluctuations in

networks that become activated during externally oriented tasks, presumably reflecting competition between opposing

processes for processing resources. Negative correlations between the DMN and the frontoparietal control network are

weaker in patients with ADHD than in people who do not have the disorder.

trajectories of cortical gyrification89. Remission of ADHD widespread deviations in cortical thickness persist in

has been associated with normalization of abnormalities many adults with ADHD. Findings include both cortical

as measured by activation during functional imaging thinning (in the superior frontal cortex, precentral cor-

tasks90, cortical thinning 91 and structural and functional tex, inferior and superior parietal cortex, temporal pole

brain connectivity 9295. and medial temporal cortex)89,96 and cortical thickening

Although these data could be taken to suggest that the (in the pre-supplementary motor area, somatosensory

age-dependent decline in the prevalence of ADHDmight cortex and occipital cortex)97. More work is needed to

be due to the late development of ADHD-associated brain determine how developmental changes in patterns of

structures and functions, most patients with ADHD do cortical thickness predict developmental changes in

not show complete developmental catchup. Indeed, ADHD symptom expression.

6 | 2015 | VOLUME 1 www.nature.com/nrdp

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

Summary Children and adolescents

Neurocognitive, neuroimaging and genetic theories The diagnosis of ADHD relies on clinical symptoms

of ADHD have shifted from single-cause or single- reported by patients or informants (including rela-

pathway models to models that delineate causes that tives and teachers), which is standard for all psychiatric

lead to ADHD through several molecular, neural and disorders12. National clinical guidelines and practice

neurocognitive pathways33,98102. These approaches have parameters for ADHD, developed over the past dec-

received clear support from aetiological studies indi- ade, show good consensus and the potential to enhance

cating that most cases of ADHD arise from a pool of evidence-based clinical practice105. Diagnosis is based

genetic and environmental risk factors. Most of these on information from a detailed clinical interview, which

risk factors have only a small effect on causal pathways. remains the gold standard. Diagnosticians ask about

Cumulative vulnerability increases ADHD trait scores, each ADHD symptom, the age of onset and resultant

and our current model suggests thatADHDemerges functional impairments. Aclinical interview aims to

when these exceed a certain threshold. In most cases, no establish whether symptoms are more extreme, persis-

single factor is necessary or sufficient to cause ADHD. tent and impairing than expected for the developmen-

However, in some patients, rare genetic variants41,42 or tal level of the patient. Validated rating scales (TABLE1)

environmental risk factors for example, psychosocial help with such decisions, as they enable informants to

deprivation54 might have a majorinfluence. quantitatively rate the behaviour of the patient at home,

The multifactorial causation of ADHD leads to a at school and in the community.

heterogeneous profile of psychopathology, neuro Several factors present challenges to clinicians aiming

cognitive deficits and abnormalities in the struc- to determine whether a diagnosis of ADHD is appro-

ture and functionof the brain. Many cases probably priate. For instance, cultural and ethnic differences can

involve dysregulation ofthe structure and function hinder diagnosis owing to variability in attitudes towards

of the frontals ubcorticalc erebellar pathways ADHD, willingness to report symptoms or the accept-

that control attention, response to reward, salience ance of the diagnosis. For example, a literature review

thresholds, inhibitory control and motor behaviour. suggested that African-American youths had more

A meta-a nalysis of peripheral biomarkers in the ADHD symptoms than Caucasian youths but were

blood and urine of drug-naive or drug-free patients diagnosed with ADHD only two-thirds as often, possi-

with ADHD and unaffected individuals found several bly owing to parent beliefs about ADHD and the lack of

measures specifically, noradrenaline, 3methoxy4 treatment access and use106. In addition, patient age can

hydroxyphenylethylene glycol (MHPG), monoamine be an issue. Developmental changes can internalize or

oxidase (MAO) and cortisol to be significantly modify some symptoms. For example, the hyperactivity

associated with ADHD56. Several of these metabolites of childhood might be experienced as inner restless-

were also related to response to ADHD medication ness in adolescence, and distractibility could manifest

and symptom severity of ADHD. These results sup- as distracting thoughts. Accordingly, self-reports from

port the idea that catecholaminergic neurotransmitter adolescents are useful, but patients can sometimes

systems (discussed in further detail in the following lack insight into their own difficulties. Furthermore,

section) and the hypothalamicpituitaryadrenal although younger children can provide useful informa-

axis are dysregulated in ADHD. Finally, genetic and tion, especially about internalizing symptoms107, parents

clinical studies also implicate other systems, including remain the main source of information for this group of

the serotonergic, nicotinic, glutamatergic and neurite patients. Parents can report on symptoms during school

outgrowthsystems. recesses and vacations when teacher reports are not

available. Although parent reports show good concur-

Diagnosis, screening and prevention rent and predictive validity 108,109, information from other

The diagnostic process for ADHD assesses the inatten informants such as teachers, when available, is valuable

tive and hyperactiveimpulsive symptom criteria for for documenting ADHD in other settings, for predicting

ADHD, evidence that symptoms cause functional prognosis and for increasing the confidence of diagno-

impairments and age of onset before 12years. Although ses110112. Finally, diagnosticians can also inquire about

ADHD is associated with other features such as execu- other medical conditions associated with symptoms

tive dysfunction62 and emotional dysregulation31,103, of ADHD, such as seizure disorders, sleep disorders,

these are commonly observed in other disorders and hyperthyroidism, physical or sexual abuse and sensory

are not core diagnostic criteria for ADHD12. To assist impairments113, as these can confound diagnosis.

diagnosis, several open access assessment tools have Although screening for ADHD is theoretically feasi

been created for use in both children (TABLE1) and adults ble given the availability of parent and self-reported

(TABLE2), and excellent, well-normed (standardized) scales (TABLE1), the few studies that have investigated the

commercial scales are available104. Importantly, patient use of early screening for ADHD have yielded inconsist-

age is relevant when assessing standard diagnostic cri- ent findings. For example, a 6-year longitudinal study

teria, such as those of the DSM or the International suggested that aparent-rated questionnaire might help

Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health with early detection, prediction and treatment plan-

Problems (ICD), owing to changes in the expression ning 114. However, owing to a lack of accurate predic-

of ADHD symptoms and impairments throughout an tors of onset, attempts at early prevention of ADHD

individuals lifetime (FIGS2,5). currently rely on population-level efforts to mitigate

NATURE REVIEWS | DISEASE PRIMERS VOLUME 1 | 2015 | 7

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

the effects of environmental risk factors for the dis screening programmes in primary care, parent training

order. Primary prevention strategies optimize maternal programmes, and specific games and play-based pro-

health during pregnancy by reducing extreme stress and grammes to enhance selfregulation when symptoms

psychosocial adversity, eliminating smoking, alcohol are identified115,116.

and drug use and reducing risk factors for preterm birth

and low birth weight. Secondary prevention approaches Adults

that detect symptoms of ADHD at an early stage Over the past 40years, clinical, family, treatment,

for example at infancy or preschoolage include longitudinal and population studies have generated

Table 1 | A selection of open access resources for assessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood

Approach Comments Websites

Interviews

Schedule for Affective A semi-structured diagnostic interview http://www.psychiatry.pitt.edu/node/8233

Disorders and Evaluates past and current psychopathology in children and

Schizophrenia in adolescents, according to DSMIV and DSM-III criteria

School Age Children Translations in many languages

(KSADS) A DSM5 version is imminent

Diagnostic Interview A structured diagnostic that uses DSMIV to assess psychopathology http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/

Schedule for Children in children and adolescents limited_access/interviewer_manual.pdf

(DISC) Translations in many languages

Child and Adolescent A semi-structured interview that evaluates current psychopathology https://devepi.duhs.duke.edu/capa.html

Psychiatric Assessment in children and adolescents

https://devepi.duhs.duke.edu/pubs/

(CAPA) Based on DSMIV criteria

papachapter.pdf

Versions for youths and preschool-aged children

Spanish and Portuguese translations

Development and For clinicians and trained non-clinicians http://www.dawba.com/b0.html

Well-Being Assessment Uses a prespecified set of questions and probes for impairment

(DAWBA) Generally used together with the SDQ

Translations in many languages

Parent Interview for A semi-structured interview focused on diagnostic criteria for ADHD, http://www.sickkids.ca/MS-Office-Files/

Child Symptoms (PICS) ODD and CD in children and adolescents Psychiatry/17145-Administration_Guidelines_

Addresses symptoms of other psychiatric disorders PICS6.pdf

Has been updated for DSM5 criteria

http://www.sickkids.ca/pdfs/Research/

Includes the TTI, which assesses symptoms of ADHD, ODD and CD in

Tannock/6013-TTI-IVManual.pdf

school, with screening questions for other psychopathology

Dutch translation

Child ADHD A structured telephone interview for teachers Available from the authors254

TTI(CHATTI) Focuses on DSMIV criteria for ADHD in school

Only available in English

Scales

Vanderbilt ADHD Versions for a parent or caregiver and teacher http://www.nichq.org/childrens-health/adhd/

Diagnostic Rating Part of the American Academy of Pediatrics ADHD Toolkit resources/vanderbilt-assessment-scales

Scales (VARS) Spanish translation

Swanson, Nolan and A rating scale for symptoms of ADHD and ODD Short scale (26item) available from: http://www.

Pelham (SNAP)-IV Can be completed by a teacher, parent or caregiver caddra.ca/pdfs/caddraGuidelines2011SNAP.pdf

Rating Scale Sensitive to changes related to treatment

Scoring guidelines available from: http://

Portuguese, Spanish and French translations

www.caddra.ca/pdfs/caddraGuidelines2011

SNAPInstructions.pdf

Full scale (90item) available from:

http://www.adhd.net/snap-iv-form.pdf

Scoring guidelines available from:

http://www.adhd.net/snap-iv-instructions.pdf

Strengths and Versions for a teacher, parent or caregiver http://www.adhd.net/SWAN_SCALE.pdf

Weaknesses of ADHD Based on DSMIV criteria

Symptoms and Normal Unusual in that the items are positively worded and it covers both

Behavior Scale (SWAN) strengths as well as weaknesses in ADHD and ODD symptoms

Spanish and French translations

SDQ Brief measure of emotional, ADHD, conduct and relationship problems http://sdqinfo.org

Versions for a parent, caregiver or teacher and a self-report

Translations in many languages

ADHD, attention-deficit/hypersensitivity disorder; CD, conduct disorder; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ODD, oppositional defiant

disorder; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; TTI, Teacher Telephone Interview.

8 | 2015 | VOLUME 1 www.nature.com/nrdp

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

Table 2 | A selection of open access resources for assessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adulthood

Approach Comments Websites

Interviews

Diagnostic Interview for Adult A structured diagnostic interview for ADHD in adults according to http://www.divacenter.eu/

ADHD, second edition (DIVA 2.0) DSMIV DIVA.aspx

A new version based on DSM5 criteria is in press

Adult (ACDS) v1.2 A semi-structured interview of current symptoms of ADHD in adults Available from the author (Lenard

Provides age-specific prompts for rating both childhood and adulthood Adler) at: http://www.med.nyu.edu/

symptoms biosketch/adlerl01

Scales

Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Developed by WHO to measure ADHD symptoms in individuals http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/

(ASRS) >18years of age ncs/asrs.php

An 18item version covers all DSMIV symptoms of ADHD

A 6item version is a screening tool validated for adolescents and adults

The 6item version (ASRS-Telephone Interview Probes for Symptoms;

ASRS-TIPS) uses semi-structured interview probes for examples of

ADHD symptoms

Both versions have been translated into many languages

Adult ADHD Investigator Incorporates suggested prompts for each ADHD item Available from Lenard Adlerat:

Symptom Rating Scale (AISRS) Descriptors for each ADHD item are explicitly defined http://www.med.nyu.edu/

Takes context into account biosketch/adlerl01

Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) Developed to retrospectively diagnose childhood ADHD in adults Available from the authors255

ADHD, attention-deficit/hypersensitivity disorder; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

very strong evidence that ADHD frequently persists satisfactory grades, a university student with ADHD

into adulthood, although its presentation changes with might need to work twice as hard as peers with the same

age23,117119 (FIG.5). Nevertheless, ADHD in adults is still aptitude to focus attention or to organize school work.

undertreated120, leading to international efforts to edu- If that restricts the students social life or causes other

cate clinicians (TABLE3) and to drive changes to DSM. problems, it might be viewed as impairing. Nonetheless,

DSM5 provides guidance about the differential expres- ADHD can be reliably diagnosed in these patients124.

sion of ADHD symptoms throughout the patients Finally, in adults with ADHD, hyperactiveimpulsive

lifetime. For instance, in contrast to young children, symptoms usually become internalized, such as feeling

adults with many impairing ADHD symptoms do not restless, and deficient emotional self-regulation125 and

typically climb on tables, have boundless energy or executive dysfunction126 become increasingly promi-

run around in a place where one should remain still. nent. Although deficient emotional regulation and

Hyperactivity in adulthood is often experienced as a executive dysfunction are not diagnostic for ADHD,

feeling of inner restlessness an internal motor that they are highly characteristic of the disorder in adults

never stops which makes it difficult for the indivi and could indicate the need for specific treatments,

dual to relax 121. By adopting symptom descriptors of such as cognitiveb ehavioural therapy, to improve

this sort, DSM5 is easier to apply to adults compared organizational or emotional self-regulationskills.

with its predecessors.

Despite these differences in symptom presentation, Heterogeneity of ADHD

the diagnostic process for adults parallels the process for Patients with ADHD show marked variation in profiles

youths in regards to documenting symptoms, impair- of symptoms, impairments, complicating factors, neuro

ment and onset of the disorder on the basis of a clinical psychological weaknesses and underlying causes127.

interview with the patient and, when available, reports Accordingly, effective partitioning of this heterogeneity

from informants. This process is aided by the avail- to refine diagnostic approaches and to provide tailored

ability of structured diagnostic interviews, such as the and targeted treatments remains an important research

Conners Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview 122, along goal. To address this aim, DSM5 recognizes three

with rating scales for patients and informants, including presentations: predominantly inattentive, predomi-

the Adult Self-Report Scale (TABLE2)123. nantly hyperactiveimpulsive and combined. These

In adulthood, additional domains of impairment presentations are no longer deemed subtypes, as in

emerge and can include difficulties related to occupa- prior versions, because they can change over time128.

tion, marriage and parenting. Patients with high intelli Moreover, even within presentations, patients greatly

gence also present with a unique set of challenges. In differ in symptom profiles. For instance, the predomi-

these individuals, impairment can be assessed relative nantly inattentive presentation applies to individuals

to their aptitude. Some of these patients go to great with a wide range of inattention and can include sub-

lengths to accommodate their symptoms, which itself threshold hyperactiveimpulsive symptoms. Although

indicates impairment to the degree that it causes distress common in population samples, inattentive ADHD

or displaces other activities. For example, to achieve is less common in the clinic, which suggests that

NATURE REVIEWS | DISEASE PRIMERS VOLUME 1 | 2015 | 9

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

Behavioural disinhibition, emotional ability Full expression of ADHD, Inattention persists and

and emergence of diagnosis in preschool years psychiatric co-morbidity, hyperactiveimpulsive symptoms wane

school failure, peer

Prodrome: hyperactivity; and speech, language rejection and Smoking Substance abuse, low self-esteem and

and motor coordination problems neurocognitive dysfunction initiation social disability

In utero Childhood Adolescence Adulthood

Genetic predisposition Psychosocial inuences, chaotic family environments, peer inuences and mismatch with school and/or work environments

Fetal exposures Dierent genetic risk factors aect the course of ADHD at dierent stages of the lifespan

and epigenetic

changes Frontalsubcorticalcerebellar dysfunction via structural and functional brain abnormalities and downregulation of

catecholamine systems that regulate attention, reward, executive control and motor functions

Clinical progression

Aetiology Persistence of cortical thickness, default-mode

Pathophysiology network and white matter tract abnormalities

Naturecases.

Figure 5 | Developmental course of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in persistent Reviews | Disease

Although noPrimers

single

sequence of events describes the pathway from in utero to adulthood, this figure describes key developmental events,

with boxes spanning their approximate onset along with hypotheses about the timing of the biological underpinnings

ofaetiological events and pathophysiological expression. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

population screening for marked inattention should be The heterogeneity of ADHD has implications for

considered, especially in female children and adults, in both research and practice. In research, the diluting

which this pattern might be particularly impairing 129. effect of heterogeneity reduces effect sizes in ADHD

Persistent inattention even at subthreshold levels is casecontrol comparisons and renders biomarkers

a key predictor of poor academic outcomes130. that are identified on the assumption that ADHD is

Psychiatric co-morbidity is another clinically impor- pathophysiologically homogeneous obsolete. Clinically,

tant dimension of ADHD heterogeneity. At one extreme, heterogeneity means that tests either neuropsycho

a small proportion of clinic-referred individuals are free logical or tests of other underlying processes that

of co-morbidity; at the other end, some patients have a focus on only one domain will be of very limited diag-

complex pattern of multiple problems, including com- nostic value. However, such assessments could help to

munication disorders, intellectual disabilities131, sleep identify specific targets for therapeutic and educational

disorders132, specific learning disabilities131, mood dis- interventions that are aimed at remediating particular

orders131, disruptive behaviour 131, anxiety disorders131, areas of impairment and weakness. For instance, indivi

tic disorders131, autism spectrum disorders131,133 and sub- duals with working memory deficits might respond

stance use disorders131,134,135. Consideration of a patients favourably to working memory training 138.

co-morbidity profile is important, as it will influence

treatment planning. Management

Pathophysiological heterogeneity might be impor- By educating patients and families, clinicians can cre-

tant clinically although new research is required to ate a framework that increases treatment adherence,

determine whether subtyping on the basis of genetic, proactively plans for continuity of treatment through-

environmental, neurobiological or neuropsycho- out the lifetime of the patient and effectively integrates

logical factors will improve diagnostic and treatment pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches.

approaches. In this regard, the largest body of evidence Education includes information about the causes of

relates to cognition. Objective tests indicate that sev- ADHD, its associated morbidity, the potential for a

eral distinct deficit profiles exist. For example, only a compromised course, the rationale for treatments and

minority of patients show a deficit in executive func- plans for key life transitions139. This education sets

tion136, which was once thought to be the core deficit in the stage for managing ADHD within a chronic care

ADHD. Other patients, who are clear of such deficits, paradigm that uses shared decision making to bol-

have problems in non-executive cognitive processes, ster treatment adherence and prepare patients for

which include those involved in basic memory and developmentalchallenges140.

temporal processing, motivational processing (delay There are geographic variations in the sequencing

tolerance or reinforcement processing) and cognitive of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treat-

energetic regulation72,73,137. Four cognitive ADHD sub- ments. For example, in the United States pharmaco

types were revealed in a study based on a community logical treatment is typically the first approach,

of children with or without ADHD70; however, whether whereas in Europe medication is usually reserved for

these subtypes predict treatment response or course severe cases or for milder cases that do not respond to

remains unclear. non-pharmacologicaltreatments141.

10 | 2015 | VOLUME 1 www.nature.com/nrdp

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

Pharmacological treatments school or work day, such as socializing, driving, doing

Before choosing a treatment, clinical experience advises homework and functioning in the familyenvironment.

several common-sense precautions. Appropriate atten- The pharmacological decision-making approach

tion needs to be given to the psychosocial environ- starts with whether the patient will benefit from a stimu

ment. In children, particular attention needs to be lant or non-stimulant treatment. Meta-analyses have

paid as to whether the family is intact or separated, demonstrated that stimulant and non-stimulant medi-

whether both parents are supportive of the childs cations for ADHD effectively reduce ADHD symptoms

treatment and whether there are any concerns about inchildren and adults142,143. By contrast, in preschool-

abuse or maltreatment. In addition, legal concerns, aged children, evidenced-based non-pharmacological

psychop athology and substance use in the parents, treatments are recommended as the first approach, when

psychosocial stressors (such as financial and medical available, but medication is indicated when symptoms

distress), access to firearms and the intellectual abilities are severe144. On average, stimulants (amphetamine

of the parents are assessed because treatments might and methylphenidate) are more efficacious than non-

not be effective in chaotic or potentially dangerous stimulants (atomoxetine, guanfacine and clonidine)145.

environments. Access to medications can also be an Accordingly, stimulants continue to be the first-line

issue, owing to a lack of health insurance or restric- psychopharmacological treatment for patients of all ages

tive policies by some governments or managed care with ADHD120.

formularies. Pharmacotherapy for ADHD will not Pharmacological treatments are typically long term,

address these issues, but appropriate social services except for those patients who do not have a persistent

or non-pharmacological interventions can mitigate course of ADHD. These treatments are generally associ-

their effects. It is important to educate parents and ated with improved outcomes in children and adults, as

patients about ADHD and its treatments to help them have been demonstrated by systematic reviews that con-

to understand the value of treatment options. sidered a range of different criteria to measure long-term

The choice of medication is guided by assessing the outcomes. For instance, a systematic review examined

severity of the symptoms, the presence of co-morbidities five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and tenopen-

(FIG.6) and what periods of the day symptom relief is label extension studies of adults with ADHD that had

needed for example, during school hours only, dur- been conducted for at least 2years146. The authors con-

ing an extended school day, during a work day or during cluded that stimulant therapy for ADHD has long-term

the evening. With few exceptions, medications to treat beneficial effects and is well tolerated. In addition, a sys-

ADHD help patients 7days a week throughout the year tematic review of adult and child studies that had been

because the condition affects aspects of life outside the carried out over at least 2years concluded that treating

Table 3 | Selected resources for clinicians, parents and patients

Organization Content Websites

US NIMH Information for patients and families http://www.nimh.nih.gov

American Professional Society for Meetings for health professionals and researchers http://www.apsard.org

ADHD and Related Disorders

ADHD World Federation Meetings for health professionals and researchers http://www.adhd-federation.org

Children and Adults with ADHD Information for patients and families http://www.chadd.org

ADHD in Adults Continuing education for health professionals http://www.adhdinadults.com

Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance Continuing education and meetings for health professionals and http://www.caddra.ca

researchers; National Clinical Guidelines for ADHD; and policy

work with the government

Australian NHMRC Information for health professionals, patients and families http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/

guidelines-publications/mh26

ADHD Europe Information for patients and families http://www.adhdeurope.eu

European Network on Adult ADHD Meetings for health professionals and researchers http://www.eunetworkadultadhd.com/

International Collaboration on Meetings for health professionals and researchers http://www.adhdandsubstanceabuse.org

ADHD and Substance Abuse

UK Adult ADHD Network Meetings for health professionals and researchers http://www.ukaan.org

ADHD India Information for patients and families http://www.adhdindia.com

China ADHD Alliance Information for patients and families http://www.adhd-china.org/en-index.htm

Zentrales adhs-netz (German Information for patients and families http://www.zentrales-adhs-netz.de

Central ADHD Network)

American Academy of Pediatrics Information for health professionals http://www2.aap.org/pubserv/

ADHD Toolkit adhd2/1sted.html

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NIMH, National Institute of Mental Health.

NATURE REVIEWS | DISEASE PRIMERS VOLUME 1 | 2015 | 11

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

Preschoolers, children and adolescents Adults

effects is prudent the goal being to provide the optimal

Parents Self-report duration of coverage throughout the day according to the

Teachers Signicant other (when available) needs of the patient151. For all stimulant formulations, the

duration of effect varies from patient to patient152. Thus,

the titration of stimulants addresses the onset and dura-

DSM-5 or ICD-10 diagnosis of ADHD tion of effect as well as overall efficacy and adverse events.

For example, long-acting stimulants take 12hours to

Preschoolers

begin working; thus, patients are told when to take the

When available, use evidenced-based non-pharmacological treatment rst medication to secure benefit at the beginning of the school

For severe symptoms, medication is indicated or work day. For some patients, the effects of long-acting

stimulants can wear off by mid-to-late afternoon, and they

might, therefore, need additional pharmacological cover-

With co-morbidity Without co-morbidity age to help to control symptoms later in the day. In such

cases, the prescription of a short-acting formulation of the

same drug can be used to extend itscoverage.

Mania and psychosis are Common adverse effects of stimulants are initial

Learning disorders, Cardiovascular

contraindications for stimulants

executive function disease and seizures

insomnia, decreased appetite, dysphoria and irritability.

Depression, tics and anxiety decits and low IQ are potential Sleep disturbances are very common in patients with

can worsen with stimulants

Substance use disorders might

are not responsive to contraindications ADHD, independent of stimulant use132, but those related

ADHD medications for stimulants

lead to abuse or diversion to stimulant use require parents to be instructed on how to

improve sleep hygiene or pharmacological management.

Figure 6 | Assessment guides management. The management | Disease Primers

of attention-deficit/

Nature Reviews

For example, a long-acting stimulant can be replaced with

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) considers psychiatric, psychological and medical

an intermediate-acting formulation, or sleep onset can be

co-morbidity. DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition;

ICD10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems,

improved with sleep aids such as melatonin153. As appe-

tenth edition; IQ, intelligence quotient. tite suppression usually occurs in the middle of the day,

its effects can usuallybe mitigated by taking the medica-

tion after breakfast. Inaddition, a substantial breakfast

ADHD improved long-term outcomes but generally and dinner as well as snacking during the day will manage

not to normal levels147. Another study found that long- energy levels and safeguard nutrition. If these measures

term medication use was associated with improved are not sufficient, nutritional supplementation can be

achievement test scores148. Furthermore, a systematic useful154. Insevere cases of weight loss or growth delays,

review of placebo-controlled discontinuation studies reducing the dose or discontinuing it over the weekend

and prospective long-term observational studies con- may be appropriate. Management of dysphoria and irri-

cluded that medication reduced ADHD symptoms and tability depends on whether these symptoms occur during

impairments, but that there was limited and inconsistent the peak or trough of the bioavailability of the medication,

evidence for long-term medication effects on improved as indicated by its pharmacokinetic curve155,156. If these

social functioning, academic achievement, employment symptoms occur during the peaks of drug bioavailabil-

status and psychiatric co-morbidity 149. Finally, although ity, switching to another stimulant is an option. If they

pharmacological approaches are generally efficacious, an occur during the troughs, they might be attributable to

important source of treatment failure is non-adherence withdrawal or rebound effects, which can be mitigated

to medication. For example, this was demonstrated in by adding a small dose of a short-acting stimulant 1hour

the 2-year followup of the Multimodal Treatment of before the symptoms occur. For patients that are sensi-

ADHD (MTA) study of children with ADHD, which tive to peaks and troughs of bioavailability, single-peak

reported that continuing medication use partly mediated formulations can be considered.

improved long-termoutcomes150. Although serious adverse effects are rare, they do

occur. The onset of tics, acute anxiety states, depression,

Stimulants. When choosing a stimulant, the first deci- psychosis and mania requires both the prompt discon-

sion is whether to use a methylphenidate product or tinuation of treatment and the search for alternative

an amphetamine product, both of which modulate the approaches consistent with emergent symptoms and diag-

action of dopamine. Methylphenidate and amphetamine noses157. Stimulants can be associated with small delays

block the dopamine transporter and amphetamine also in growth in height, but these tend to attenuate with time

promotes the release and reverse transport of dopamine. and seem not to affect ultimate height and weight in adult-

Although the efficacy of both classes of stimulants is hood158. Nevertheless, abnormal growth parameters can

similar, some patients preferentially respond to and toler- indicate the need to change treatments. Evidence for the

ate one or the other 143. There are no reliable predictors association of other serious adverse events with stimulant

of individual patient responses. Both families of stimu- use for ADHD is less robust. For example, some studies

lants have short-acting (24hours), intermediate-acting have raised concerns that stimulants cause sudden car-

(68hours) and long-acting (1012hours) formulations diac death, and one Danish study (n=714,258) found that

that enable clinicians to tailor duration of coverage for stimulant use was associated with an increased riskof

each patient. Starting the patient on a low dose andtitrat- any adverse cardiovascular event (adjusted hazard ratio

ing at weekly intervals depending on response and adverse of 1.83). These data from the Danish study are difficult

12 | 2015 | VOLUME 1 www.nature.com/nrdp

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

to interpret because the category of any included hyper- disorder is appropriately managed, ADHD can then be

tension, rheumatic fever and cardiovascular disease not treated effectively 170. As a result, combined treatments

otherwise specified; this final category accounted for are frequently used for the management of ADHD in

40% of cases159. Moreover, a study from the United States individuals withco-morbidity.

(n=1,200,438) reported that ADHD drugs (methylpheni- For patients with active substance use disorders,

date, amphetamine and atomoxetine) did not increase the stimulants are contraindicated or are used cautiously,

risk of serious cardiovascular events in children and young owing to concerns about the potential for abuse, mis-

adults160. The same was true for a subanalysis limited to use or diversion by the patient or caregiver. Such con-

methylphenidate, which was the only drug with sufficient cerns contrast with substantial literature that indicates

data. Inaddition, a meta-analysis of observational stud- stimulant use in childhood has a protective effect on

ies concluded that ADHD drugs (mostly methylphenidate subsequent smoking 171 and neutral or protective effects

and amphetamine) did not increase the risk of sudden on subsequent drug and alcohol use disorders172175.

death in children161. Thus, for patients with pre-existing However, substantial data indicate that a minority of

cardiac conditions, stimulants should be used cautiously patients with ADHD divert their stimulant medication

and only after consultation with a cardiologist162,163, and in for misuse byothers176.

all patients treated with stimulants, blood pressure should Atomoxetine has been tested successfully in the

be monitored during treatment. Stimulants can be used management of ADHD in the context of co-morbidity

cautiously or not at all in the presence of tic, bipolar, with tics, anxiety and depression177,178, and one review

anxiety, and substance use disorders and seizures. suggested that 2adrenergic agonists yield the best

combined improvement for ADHD that is co-morbid

Non-stimulants. Two classes of non-stimulants have with tic disorders179. Bupropion is approved for use in

been approved by regulatory agencies for the treatment depression in adults, and its efficacy in ADHD has been

of ADHD. These include the selective noradrenaline confirmedin a meta-analysis180. Some reports have docu

reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine164 and long-acting formu- mented the efficacy of stimulants181, extended-release

lations of two 2adrenergic agonist drugs clonidine165 guanfacine182 and atomoxetine183 for the treatment of

and guanfacine166. These drugs are effective in the manage- comorbid oppositional defiant disorder symptoms.

ment of ADHD, but the sedative effects of 2adrenergic When treated with ADHD medications, patients with

agonists limit their use in somepatients165,167. intellectual disabilities184 or traumatic brain injury 185

Similar to stimulants, these medications require slow show a reduction in ADHD symptoms. General cog-

titration to avoid adverse effects by starting with a low nitive ability is not responsive to ADHD pharmaco

dose and adjusting it based on outcomes. Atomoxetine therapy; however, some data suggest that atomoxetine

can be administered once or twice daily. Long-acting can modestly improve dyslexia186 and that stimulants187

guanfacine was tested in children and found to be more and atomoxetine 188 yield modest improvements in

effective at higher doses, but these doses were associated behavioural measures of executive functioning as well

with more adverse effects. 2adrenergic agonists can as performance on executive memory, reaction time and

also be administered once or twice daily. Their efficacy inhibitory control tasks72. Although some academic per-

has been documented for young children but not for formance problems associated with symptoms of ADHD

adolescents andadults. (for example, homework completion) can improve with

Combined therapy with stimulants and atomoxetine or treatment, medication cannot replace missing skills,

a long-acting 2adrenergic agonist might be effective for improve academic achievement scores or ameliorate

patients who have been unresponsive to monotherapy 168, specific learningdisabilities189.

but the implications of these combined therapies for Taken together, it is clear that finding an effective for-

cardiovascular safety have not been adequately studied. mulation, daily dose and dosing schedule for an ADHD

Patients who do not respond to stimulants, atomoxetine medication is crucial for successful treatment. The use

or 2adrenergic agonists might respond to other medica- of tools such as management decision trees that sum-

tions that have been used off-label in the management of marize recommendations about pharmacotherapy and

ADHD, such as tricyclic antidepressants, bupropion (an the integration of non-pharmacological treatments can

antidepressant) or modafinil (a wakefulness-promoting be useful in guiding ADHD management (FIG.7). The

agent that is commonly used to treat narcolepsy). efficacy of these treatments will be augmented by moni-

Although some data support the efficacy of these off- toring both symptomatic and functional outcomes and

label medications for the treatment of ADHD169, regula- promotingadherence151.

tory agencies in the United States and the European Union

have not approved their use in thiscontext. Non-pharmacological treatments

Non-pharmacological approaches for the treatment of

Psychiatric co-morbidity. The co-morbidities of ADHD ADHD might be required for several reasons. First, some

affect the clinical picture of this disorder and its manage- patients do not respond positively to medication and

ment. The rule of thumb is to address the most serious might experience, for example, poor symptom control,

disorder first. For example, it would be almost impos- unmanageable adverse events or both. Second, medica-

sible to manage ADHD in the presence of a serious, tion alone might not produce optimal results across all

active mood or substance use disorder; these conditions domains of ADHD-related impairment. Third, patients

need to be addressed first. However, when the other might not have access to medication because of either

NATURE REVIEWS | DISEASE PRIMERS VOLUME 1 | 2015 | 13

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

PRIMER

parent or clinician concern or restrictive government supplementation with free fatty acids, but the clinical

policies that limit access. Even in jurisdictions where effects were small193. Insufficient evidence supports

medications are licensed and available, there are varia- other supplement types, for example, vitamins or