Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Ruling: Partisan Elections For Utah Board of Education 'Unconstitutional'

Transféré par

The Salt Lake Tribune100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

5K vues6 pagesIn a ruling issued Monday, Dec. 11, 2017, 3rd District Court Judge Andrew Stone ruled that Senate Bill 78 runs afoul of the Utah Constitution by making elections of Utah Board of Education members partisan.

Titre original

Ruling: Partisan elections for Utah Board of Education 'unconstitutional'

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentIn a ruling issued Monday, Dec. 11, 2017, 3rd District Court Judge Andrew Stone ruled that Senate Bill 78 runs afoul of the Utah Constitution by making elections of Utah Board of Education members partisan.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

5K vues6 pagesRuling: Partisan Elections For Utah Board of Education 'Unconstitutional'

Transféré par

The Salt Lake TribuneIn a ruling issued Monday, Dec. 11, 2017, 3rd District Court Judge Andrew Stone ruled that Senate Bill 78 runs afoul of the Utah Constitution by making elections of Utah Board of Education members partisan.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 6

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE THIRD JUDICIAL DISTRICT

IN AND FOR SALT LAKE COUNTY, STATE OF UTAH.

DR. A. LeGRAND RICHARDS, an individual, MEMORANDUM DECISION

KATHLEEN McCONKIE, an individual,

RANDY MILLER, an individual, CAROL CASE NO. 170904078

BARLOW LEAR, an individual, THE UTAH

PTA, a non-profit corporation, UTAHNS FOR

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, INC., a non-profit Judge Andrew H. Stone

Corporation, and ABU EDUCATION FUND, a

non-profit corporation,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

SPENCER COX, as Lieutenant Governor of the

State of Utab,

Defendant.

This matter came before the Court on November 22, 2017, for a hearing in connection with the

following Motions: (1) Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction; (2) defendant’s Motion for Partial

Summary Judgment; and (3) plaintiffs? Cross-Motion for Partial Summary Judgment on Art. X Issues. At

the conclusion of the hearing, the Court took the matter under advisement to further consider the parties?

written submissions, the relevant legal authorities and counsel’s oral argument. Being now fully

informed, the Court rules as stated herein.

The plaintiffs’ Complaint challenges the constitutionality of Senate Bill 78 (“SB 78") which

amends the Election Code, Utah Code Annotated § 20A-1-101, et. seq., as it relates to the election of

Utah State Board of Education (“Board”) members. The parties agree that as a result of this amendment,

beginning with the 2018 election year, Board members are to be elected in a partisan election. In

RICHARDS V. COX PAGE 2 MEMORANDUM DECISION

particular, Utah Code § 20A-14-104.1 requires a person who wishes to become a candidate for School

Board to go through ordinary means (including a process where candidates ordinarily declare a political

affiliation) and, more directly, declares “The office of State School Board of Education member is a

partisan office.” § 20A-14-104.1(2).

‘The plaintiffs assert that the amendment is an unconstitutional violation of article X, section 8 of

the Utah Constitution, which provides: “No religious or partisan test or qualification shall be required as a

condition of employment, admission, or attendance in the state's education systems.” The defendant

maintains that even if candidates for the Board are now required to follow the general election

procedures, (1) article X, section 8 does not prohibit partisan activity in connection with Board member

elections, it only prohibits a “partisan test,” and (2) Board members are elected officials rather than

employees and therefore fall outside the scope of article X, section 8. The Court addresses these

arguments in turn,

“In interpreting the state constitution, we look primarily to the language of the constitution itself

{OJur Constitution ... should be interpreted and applied according to the plain import of [its] language

as it would be understood by persons of ordinary intelligence and experience. We need not inquire

beyond the plain meaning of the [constitutional provision] unless we find it ambiguous.” T-Mobile USA,

Inc. v. Utah State Tax Com'n, 254 P.3d 752, 762 (Utah 2011).

According to the defendant, in prohibiting a “partisan test,” article X, section 8 prohibits only “an

actual test - ie. that the person must be a member of a particular partisan political party (or not be a

member of a specific partisan political party).” (Defendant's Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiffs’

Motion for Preliminary Injunction at p. 13). The defendant asserts that “in this case there is no partisan

RICHARDS V. COX PAGE 3 MEMORANDUM DECISION

test, Candidates for the State Schoo! Board can run as a candidate of [a] political party, as a candidate

unaffiliated with a party, or as a write-in candidate... There is no bar based upon a partisan qualification

to become a candidate or to be elected, nor is there any bar of a member of any particular poli

ical party

from being a candidate or being elected.” Id, at p. 6

The language here is plain English, and, given its comparatively recent adoption in its current

form in 1986, is hardly ancient text requiring complex interpretation. The focus of this phrase is not, as

the defendant suggests, on whether a candidate may choose to run as a member of a particular party or

not, but rather on whether the Board member selection process is independent of partisan politics. There

is perhaps no more partisan a test than a contested, partisan election. In other words, the plain meaning

which the Court gives to this constitutional provision is to prohibit the selection of Board members with a

partisan election which permits candidates to designate a political party affiliation. For instance, the

defense rationalizes that a particular candidate for the Board may run as unaffiliated. However, that

candidate’s opponent may be identified with a particular party which would be designated on the ballot,

thus undeniably and impermissibly injecting partisanship into the election process. In such a case, at least

that election requires a partisan test. At its essence, it is the declaration of Board membership as a

partisan office that violates the plain import of the partisan prohibition in article X, section 8.

In addition, the Court rejects the defendant’s view that article X, section 8 does not apply to

Board members because they are elected officials and not employees. Again, the Court need not inquire

beyond the plain and ordinary meaning of “employment,” to determine that Board members meet the

indicia of employment. As outlined in the plaintiffs’ Brief Supporting First Motion for Preliminary

Injunctive Relief, and in particular the Lear Declaration, Board members ate paid a salary. The state

RICHARDS V. COX PAGE 4 MEMORANDUM DECISION

withholds federal and state taxes, including Social Security and Medicare taxes. Members are provided

with state-sponsored health insurance. Therefore, according to its plain meaning, Board members hold

“employment” in a legal sense in the State’s education system and therefore fall within the purview of

article X, section 8,

Even if State Board members did not meet the legal definition of “employment,” that focus is, in

fact, too narrow. It is unreasonable to expect that the voters, in passing on the constitutional language,

were focused on a narrow legal test of the term. Sec. 8 of Article X refers broadly to “employment ... in

the state’s education systems.” The same Article vests “general control and supervision of the public

education system” in the state Board. Under ordinary meaning, voters approving Section 8 would

understand that those specifically charged with supervising and controlling the education system are

“employed” in that system.

Admittedly, this is a closer question than whether an election with declared parties is a partisan

test. Section 2 of Article X defines the state’s public and higher education systems, and makes no mention

of the State Board, which is provided for in Section 3. Arguably, the State Board is employed in the broad

sense of the word in education, but not in the state's education systems, as proscribed by Section 8. In the

broad meaning of the word employment, the Legislative and the Executive Branches are each “employed”

to some extent in setting policy for education, but that plainly is not “employment . . . in the state’s

education systems.” A line must be drawn somewhere. Ultimately, however the Board's specific Section

3 power of “general control and supervision of the public education system” leads the Court to conclude

that the most natural reading of the Section 8 proscription would include the Board as being employed in

that system

RICHARDS V. COX PAGE 5 MEMORANDUM DECISION

Based on the foregoing, the Court grants the plaintiffs’ cross-Motion for Partial Summary

Judgment with respect to the plaintiffs’ First Claim for Relief, asserting that SB 78 violates article X,

section 8. The Court also grants the plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction. The Court’s granting

of Plaintiffs’ Motion for Partial Summary Judgment indicates a strong likelihood of success on the merits

The requirement that plaintiffs seek election in a partisan process constitutes irreparable harm-the nature

of their respective campaigns and their chances of ig are clearly not compensable in monetary

damages or by subsequent declaration. The balance of the harms falls equally on the parties, though the

Court notes that an injunction will more closely preserve the current status quo. Finally, because in the

Court’s view an injunction is necessary to give effect to the constitutional provision, it does not offend the

public interest to grant it. The Court denies the defendants’ Motion for Partial Summary Judgment.

Counsel for the plaintiffs is to prepare an Order consistent with this Memorandum Decision and

should submit the same to the Court for review and entry.

Dated

is_// day of December, 2017.

‘ANDREW H. STONE,

DISTRICT COURT JUDGE.

RICHARDS V. COX PAGE 6 MEMORANDUM DECISION

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

T hereby certify that I emailed/mailed a true and correct copy of the foregoing Memorandum

Decision, to the following, this }]4“~_ day of December, 2017:

David R. Irvine

Attomey for Plaintiffs

747 E, South Temple, Suite 130

Salt Lake City, Utah 84102

Drirvine@aol

Alan L. Smith

Attomey for Plaintiffs

1169 East 4020 South

Salt Lake City, Utah 84124

Alanakaed@aol.com

‘Thom D. Roberts

Greg Soderberg

Assistant Attorneys General

Attomeys for Defendant

P.O. Box 140857

160 East 300 South, Fifth Floor

Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-0857

thomroberts@agutah.gov

gsoderberg@agutah.gov

Guecler

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Salt Lake City Council text messagesDocument25 pagesSalt Lake City Council text messagesThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- NetChoice V Reyes Official ComplaintDocument58 pagesNetChoice V Reyes Official ComplaintThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Richter Et Al 2024 CRB Water BudgetDocument12 pagesRichter Et Al 2024 CRB Water BudgetThe Salt Lake Tribune100% (4)

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Petition For Rehearing in James Huntsman's Fraud CaseDocument66 pagesThe Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Petition For Rehearing in James Huntsman's Fraud CaseThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers LetterDocument3 pagesU.S. Army Corps of Engineers LetterThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Upper Basin Alternative, March 2024Document5 pagesUpper Basin Alternative, March 2024The Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Park City ComplaintDocument18 pagesPark City ComplaintThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Spectrum Academy Reform AgreementDocument10 pagesSpectrum Academy Reform AgreementThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Goodly-Jazz ContractDocument7 pagesGoodly-Jazz ContractThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Opinion Issued 8-Aug-23 by 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in James Huntsman v. LDS ChurchDocument41 pagesOpinion Issued 8-Aug-23 by 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in James Huntsman v. LDS ChurchThe Salt Lake Tribune100% (2)

- Settlement Agreement Deseret Power Water RightsDocument9 pagesSettlement Agreement Deseret Power Water RightsThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Teena Horlacher LienDocument3 pagesTeena Horlacher LienThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Gov. Cox Declares Day of Prayer and ThanksgivingDocument1 pageGov. Cox Declares Day of Prayer and ThanksgivingThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Unlawful Detainer ComplaintDocument81 pagesUnlawful Detainer ComplaintThe Salt Lake Tribune100% (1)

- Superintendent ContractsDocument21 pagesSuperintendent ContractsThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- David Nielsen - Memo To US Senate Finance Committee, 01-31-23Document90 pagesDavid Nielsen - Memo To US Senate Finance Committee, 01-31-23The Salt Lake Tribune100% (1)

- Employment Contract - Liz Grant July 2023 To June 2025 SignedDocument7 pagesEmployment Contract - Liz Grant July 2023 To June 2025 SignedThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Wasatch IT-Jazz ContractDocument11 pagesWasatch IT-Jazz ContractThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Final Signed Republican Governance Group Leadership LetterDocument3 pagesFinal Signed Republican Governance Group Leadership LetterThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- 2023.03.28 Emery County GOP Censure ProposalDocument1 page2023.03.28 Emery County GOP Censure ProposalThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- HB 499 Utah County COG LetterDocument1 pageHB 499 Utah County COG LetterThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Ruling On Motion To Dismiss Utah Gerrymandering LawsuitDocument61 pagesRuling On Motion To Dismiss Utah Gerrymandering LawsuitThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- US Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022Document5 pagesUS Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022The Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- SEC Cease-And-Desist OrderDocument9 pagesSEC Cease-And-Desist OrderThe Salt Lake Tribune100% (1)

- PLPCO Letter Supporting US MagDocument3 pagesPLPCO Letter Supporting US MagThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- US Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022Document5 pagesUS Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022The Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- US Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022Document5 pagesUS Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022The Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Utah Senators Encourage Gov. DeSantis To Run For U.S. PresidentDocument3 pagesUtah Senators Encourage Gov. DeSantis To Run For U.S. PresidentThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

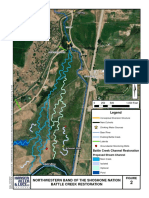

- EWRP-035 TheNorthwesternBandoftheShoshoneNation Site MapDocument1 pageEWRP-035 TheNorthwesternBandoftheShoshoneNation Site MapThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Proc 2022-01 FinalDocument2 pagesProc 2022-01 FinalThe Salt Lake TribunePas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)