Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A Case Study About Reducing Waste and Saving Costs: by Davis R. Bothe

Transféré par

jrcg0914Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Case Study About Reducing Waste and Saving Costs: by Davis R. Bothe

Transféré par

jrcg0914Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

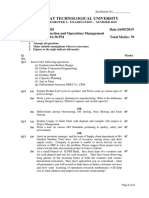

11/9/2017

Use Run Charts To Confirm Root Causes

A case study about reducing waste and saving costs

by Davis R. Bothe

After completing a Pareto analysis of his company's scrap costs, George, the plant manager, discovered that the biggest problem

the company faced was that of oversized bores on cylinder blocks. To learn more about the problem, George quizzed Vickie, the

supervisor of the department where blocks were machined. She was well aware of the situation and explained that the complexity

of the operation made the process difficult for employees to master.

Unfortunately, due to ongoing layoffs, the machinist who originally ran the job was bumped to a lower paying position. Since

then, a series of operators had taken over, none of whom had remained long enough to adequately learn how to run this delicate

piece of equipment. According to Vickie, the personnel changes couldn't be controlled because they were a "union thing."

Vickie said that she once proposed a training center where new operators could learn how to run this equipment before actually

working on the floor. But because her proposal was rejected (budget constraints), Vickie decided to display posters in that area,

reminding operators that quality is one of their main responsibilities.

Validating the root cause

Wondering if there was a way to confirm Vickie's theory that inexperienced operators were the root cause of the

scrap, George asked the quality department for the scrap reports for the past several months. He then plotted

the daily percentage of scrap on a run chart (see Figure 1).

George next reviewed records that tracked which employees had worked this particular job within the last three months. He

overlaid the employment durations of these operators on the x axis of the run chart to determine if a relationship existed between

the change in operators and the scrap rate.

This analysis clearly showed that although the scrap rate certainly varied over time, it didn't match the changes in operators.

Operator A, for example, started with a low scrap rate, but his rate increased the longer he stayed on the job. If high scrap was

related to a lack of operator experience, operator A certainly didn't bear this out. Operator D's scrap rate, on the other hand,

began high, went low, went high again and ended low. The reverse of this pattern occurred for operator E.

Not perceiving any discernible link between scrap and operator changes, George realized that another variable must exist.

After asking some of his manufacturing engineers for ideas about what could cause bore size variation, George

zeroed in on the brand of insert installed in the machine. He gathered information from the maintenance

department on which brand (X or Y) was used during what time period. He then overlaid this usage rate on the

run chart of scrap (see Figure 2). He noticed that brand X inserts were in the machine when the scrap rate was high, while brand

Y inserts were used when the rate was low.

Testing and proving the theory

George returned to the cylinder boring operation. Learning that the scrap rate was high that day, he stopped production, removed

the inserts (which were brand X as he expected) and replaced them with brand Y inserts. The scrap rate for the remainder of the

day took a spectacular nosedive, as he had predicted.

The next day George had the maintenance personnel reinstall the set of brand X inserts that were removed the day before. The

scrap rate for oversize bores immediately jumped, verifying the link between insert vendor and scrap. And when the use of

supplier X's inserts was banned, the scrap rate for oversized bores dropped by more than 70%.

DAVIS R. BOTHE is the director of quality improvement at the International Quality Institute in Cedarburg, WI. He earned a

master's degree in applied math and physics from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Bothe is an ASQ certified quality

engineer and reliability engineer. He is an ASQ Fellow.

If you would like to comment on this article, please post your remarks on the Quality Progress Discussion Board, or e-mail them

to editor@asq.org.

Copyright © 2005-2014 American Society for Quality. All rights reserved.

Republication or redistribution of ASQ content is expressly prohibited without the prior written consent.

ASQ shall not be liable for any errors in the content, or for any actions taken in reliance thereon.

1/1

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Guidelines for Siting and Layout of FacilitiesD'EverandGuidelines for Siting and Layout of FacilitiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Root Cause Analysis Handbook: A Guide to Efficient and Effective Incident InvestigationD'EverandRoot Cause Analysis Handbook: A Guide to Efficient and Effective Incident InvestigationPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Studies in Engineering EthicsDocument8 pagesCase Studies in Engineering EthicsMitsui Konttori100% (2)

- Echartered Engineering Competency Claims - Example C 01082013Document27 pagesEchartered Engineering Competency Claims - Example C 01082013lwise86Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection On Grant Garraway's TalkDocument2 pagesReflection On Grant Garraway's TalkShee AnnPas encore d'évaluation

- Se CT 1 AnswerDocument5 pagesSe CT 1 AnswerMary Joy Paclibar BustamantePas encore d'évaluation

- Lessons Learned in Startup and Commissioning of Simple Cycle and Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine PlantsDocument114 pagesLessons Learned in Startup and Commissioning of Simple Cycle and Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine PlantsTerry A. Waldrop50% (4)

- Brian Waghorn Resume 081720Document2 pagesBrian Waghorn Resume 081720api-346519251Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fast Drill Borehole ManagementDocument18 pagesFast Drill Borehole ManagementLucas CabralPas encore d'évaluation

- APEGGA Ethics QuestionsDocument11 pagesAPEGGA Ethics QuestionsMuzaffar Siddiqui50% (2)

- Module: Engineering Professionalism (MECH 4201) ProgrammeDocument7 pagesModule: Engineering Professionalism (MECH 4201) ProgrammeFarhaan BudalyPas encore d'évaluation

- SMTL 02 Iipp PDFDocument27 pagesSMTL 02 Iipp PDFRecordTrac - City of OaklandPas encore d'évaluation

- POM Summer 2019Document4 pagesPOM Summer 2019hunnyPas encore d'évaluation

- Agile Teams Require Agile QA: How To Make It Work, An Experience ReportDocument7 pagesAgile Teams Require Agile QA: How To Make It Work, An Experience ReportSangramPas encore d'évaluation

- Ldrs 890 Internship ProposalDocument10 pagesLdrs 890 Internship Proposalapi-409579490Pas encore d'évaluation

- PortfolioDocument9 pagesPortfolioapi-290279144Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Case of Occidental Engineering INGLÈSDocument2 pagesThe Case of Occidental Engineering INGLÈSAndrés MesíaPas encore d'évaluation

- 02 Team Feasibility CommitmentDocument2 pages02 Team Feasibility CommitmentZeeshan Pathan100% (2)

- BER Case 08-2-FINALDocument4 pagesBER Case 08-2-FINALDhia EmpayarPas encore d'évaluation

- ABS Jackup Safety White PaperDocument8 pagesABS Jackup Safety White PaperFoad MirzaiePas encore d'évaluation

- Reliability Growth Cause Analysis TutorialDocument12 pagesReliability Growth Cause Analysis TutorialAkshay SetlurPas encore d'évaluation

- Experiences in Reverse-Engineering of A "Nite Element Automobile Crash ModelDocument18 pagesExperiences in Reverse-Engineering of A "Nite Element Automobile Crash ModelArunachalam MuthiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Ergonomics Implementation, The Right Way and The Wrong WayDocument4 pagesErgonomics Implementation, The Right Way and The Wrong Waypkj009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aircraft Manufacturing Concession: Non-Conforming Part From Manufacturing. Release As Concession RequestDocument4 pagesAircraft Manufacturing Concession: Non-Conforming Part From Manufacturing. Release As Concession Requestkrishbalu17Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ational Etrochemical Efiners Ssociation Treet Uite AshingtonDocument19 pagesAtional Etrochemical Efiners Ssociation Treet Uite AshingtonVijayakumarNarasimhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Mod 3 - Human Resource PcaDocument4 pagesMod 3 - Human Resource Pcaapi-654684323Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chen 2010Document20 pagesChen 2010Daniel Robayo ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- MJohnston MascDocument95 pagesMJohnston MascSahil ChouhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Waste Shell Cement CompositesDocument70 pagesWaste Shell Cement CompositesBenchaabene KhouloudPas encore d'évaluation

- EPRI Cycle Chemistry Upsets During OperationDocument42 pagesEPRI Cycle Chemistry Upsets During OperationraharjoitbPas encore d'évaluation

- Inspection Quality Depends On People, Procedures, and PoliciesDocument10 pagesInspection Quality Depends On People, Procedures, and PoliciesRaja APas encore d'évaluation

- Why It's A Mistake To Reuse Old Coating SpecsDocument2 pagesWhy It's A Mistake To Reuse Old Coating SpecsJosé AvendañoPas encore d'évaluation

- Quality Improvement Incentives and Product Recall Cost Sharing ContractsDocument17 pagesQuality Improvement Incentives and Product Recall Cost Sharing ContractsMisdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lessons Learned in Startup and Commissioning of Simple Cycle and Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine PlantsDocument114 pagesLessons Learned in Startup and Commissioning of Simple Cycle and Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine Plantsphoenix609100% (1)

- MICHAEL BROWN-NSI-Planning and Scheduling Machine PDFDocument7 pagesMICHAEL BROWN-NSI-Planning and Scheduling Machine PDFRAMONPas encore d'évaluation

- Lessons Learned Document SampleDocument3 pagesLessons Learned Document SampleiatiamPas encore d'évaluation

- Code of EthicsDocument5 pagesCode of Ethicsمهند علي محمدPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1 CMPMDocument11 pagesModule 1 CMPMJohn AtigPas encore d'évaluation

- OSHA Mobile Crane Inspection GuidelinesDocument34 pagesOSHA Mobile Crane Inspection GuidelinesAhmed Imtiaz RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Babbitted Bearing Health AssessmentDocument15 pagesBabbitted Bearing Health AssessmentZeeshan AnwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Condition Survey - The Backbone of A Good Coating SpecificationDocument4 pagesCondition Survey - The Backbone of A Good Coating SpecificationJosé AvendañoPas encore d'évaluation

- On-Line Vibration Technology Development: Feasibility of Commercialization of TechnologyDocument50 pagesOn-Line Vibration Technology Development: Feasibility of Commercialization of TechnologyDante Filho100% (1)

- What Does It Cost To Fix A DefectDocument8 pagesWhat Does It Cost To Fix A DefectNayo GallePas encore d'évaluation

- A Good Report Writng GuideDocument3 pagesA Good Report Writng Guideomolewa joshuaPas encore d'évaluation

- B0a43 2020 Civ Practice Exam 97 1Document16 pagesB0a43 2020 Civ Practice Exam 97 1habibhabibo492Pas encore d'évaluation

- Training Simulators Smooth OperationsDocument2 pagesTraining Simulators Smooth Operationsfawmer61Pas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering Professionalism ENG101: Case Studies For The Design ProcessDocument16 pagesEngineering Professionalism ENG101: Case Studies For The Design ProcessAbdullah Masood0% (1)

- IEng PresentationDocument5 pagesIEng PresentationBabatunde OlaitanPas encore d'évaluation

- Defect Bug Life Cycle in Software TestingDocument7 pagesDefect Bug Life Cycle in Software TestingArnabPas encore d'évaluation

- AACE - 25r-03Document32 pagesAACE - 25r-03Duncan Anderson100% (2)

- Task6 PDFDocument3 pagesTask6 PDFReda Mashal100% (1)

- T. J. Roosen and D. J. Pons (2013) : William M. Goriwondo, Samson Mhlanga, Alphonce Marecha (2011)Document6 pagesT. J. Roosen and D. J. Pons (2013) : William M. Goriwondo, Samson Mhlanga, Alphonce Marecha (2011)harun aliPas encore d'évaluation

- ITSU3007 Manage IT Projects: Final AssessmentDocument8 pagesITSU3007 Manage IT Projects: Final Assessmentyatin gognaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mechanical Integrity: "You Get What You Inspect, Not What You Expect!"Document1 pageMechanical Integrity: "You Get What You Inspect, Not What You Expect!"Vu Hoang VoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2015 05 AIChE Beacon - Mechanical Integrity PDFDocument1 page2015 05 AIChE Beacon - Mechanical Integrity PDFAD DaoudPas encore d'évaluation

- Increasing Demand For Composite Driveshafts Leads To Automated Production - CompositesWorldDocument7 pagesIncreasing Demand For Composite Driveshafts Leads To Automated Production - CompositesWorldAnonymous r3MoX2ZMTPas encore d'évaluation

- (Conciseness) Create Strong VerbsDocument11 pages(Conciseness) Create Strong Verbs柯泰德 (Ted Knoy)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Advances in Drillpipe Fatigue ManagementDocument1 pageAdvances in Drillpipe Fatigue ManagementFares NaceredinePas encore d'évaluation

- Implementation Manual - 3 Quality Maintenance Qs. 1 What Kind of Data Is Required? Ans: Quality Defects - In-House and at Customer EndDocument8 pagesImplementation Manual - 3 Quality Maintenance Qs. 1 What Kind of Data Is Required? Ans: Quality Defects - In-House and at Customer Endagus wahyudiPas encore d'évaluation

- Estimation A Skill For Every EngineerDocument31 pagesEstimation A Skill For Every Engineerjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- What Every Engineer Should KnowDocument6 pagesWhat Every Engineer Should Knowjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy of A Stematic ReviewDocument2 pagesAnatomy of A Stematic Reviewjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2011 Huang. No Parametric VariogramDocument15 pages2011 Huang. No Parametric Variogramjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Process Simulation First StepsDocument62 pagesProcess Simulation First Stepsjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Getting Started Guide For TeachersDocument65 pagesGetting Started Guide For Teachersjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Best Source - Code QualityDocument61 pagesThe Best Source - Code Qualityjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bright Lights,: Big ProblemsDocument72 pagesBright Lights,: Big Problemsjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introductory Probability Theory PDFDocument299 pagesIntroductory Probability Theory PDFjrcg0914100% (1)

- Water: A Nonparametric Stochastic Approach For Disaggregation of Daily To Hourly Rainfall Using 3-Day Rainfall PatternsDocument13 pagesWater: A Nonparametric Stochastic Approach For Disaggregation of Daily To Hourly Rainfall Using 3-Day Rainfall Patternsjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Continuous Improvement Manager: TasksDocument2 pagesContinuous Improvement Manager: Tasksjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Support Vector Machin, An Excellent ToolDocument36 pagesSupport Vector Machin, An Excellent Tooljrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aztec Autumn by Gary Jennings - Several ReviewsDocument6 pagesAztec Autumn by Gary Jennings - Several Reviewsjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- P Diagram - Art PDFDocument85 pagesP Diagram - Art PDFjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Operational Performance ManagementDocument1 pageOperational Performance Managementjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Data CollectionDocument19 pagesData Collectionjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- SPC For EverydayDocument8 pagesSPC For Everydayjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Beer Brewing PfmeaDocument144 pagesBeer Brewing Pfmeajrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Milstd - 1629A - 04 - Fmeca PDFDocument1 pageMilstd - 1629A - 04 - Fmeca PDFjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Alternative Fuels Technology: A Necessity or A Vogue?: Roberto CantúDocument25 pagesAlternative Fuels Technology: A Necessity or A Vogue?: Roberto Cantújrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aztec Autumn by Gary Jennings - Several ReviewsDocument6 pagesAztec Autumn by Gary Jennings - Several Reviewsjrcg0914Pas encore d'évaluation

- Careem STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT FINAL TERM REPORTDocument40 pagesCareem STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT FINAL TERM REPORTFahim QaiserPas encore d'évaluation

- Small Signal Analysis Section 5 6Document104 pagesSmall Signal Analysis Section 5 6fayazPas encore d'évaluation

- CavinKare Karthika ShampooDocument2 pagesCavinKare Karthika Shampoo20BCO602 ABINAYA MPas encore d'évaluation

- Shopnil Tower 45KVA EicherDocument4 pagesShopnil Tower 45KVA EicherBrown builderPas encore d'évaluation

- Gis Tabels 2014 15Document24 pagesGis Tabels 2014 15seprwglPas encore d'évaluation

- QCM Part 145 en Rev17 310818 PDFDocument164 pagesQCM Part 145 en Rev17 310818 PDFsotiris100% (1)

- Data Sheet: Elcometer 108 Hydraulic Adhesion TestersDocument3 pagesData Sheet: Elcometer 108 Hydraulic Adhesion TesterstilanfernandoPas encore d'évaluation

- ELC Work DescriptionDocument36 pagesELC Work DescriptionHari100% (1)

- DT2 (80 82)Document18 pagesDT2 (80 82)Anonymous jbeHFUPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods of Teaching Syllabus - FinalDocument6 pagesMethods of Teaching Syllabus - FinalVanessa L. VinluanPas encore d'évaluation

- Installation and User's Guide For AIX Operating SystemDocument127 pagesInstallation and User's Guide For AIX Operating SystemPeter KidiavaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Relevant Cost For Decision: Kelompok 2Document78 pagesRelevant Cost For Decision: Kelompok 2prames tiPas encore d'évaluation

- GATE General Aptitude GA Syllabus Common To AllDocument2 pagesGATE General Aptitude GA Syllabus Common To AllAbiramiAbiPas encore d'évaluation

- 950 MW Coal Fired Power Plant DesignDocument78 pages950 MW Coal Fired Power Plant DesignJohn Paul Coñge Ramos0% (1)

- MCS Valve: Minimizes Body Washout Problems and Provides Reliable Low-Pressure SealingDocument4 pagesMCS Valve: Minimizes Body Washout Problems and Provides Reliable Low-Pressure SealingTerry SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Sworn Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net WorthDocument3 pagesSworn Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net WorthShelby AntonioPas encore d'évaluation

- FBW Manual-Jan 2012-Revised and Corrected CS2Document68 pagesFBW Manual-Jan 2012-Revised and Corrected CS2Dinesh CandassamyPas encore d'évaluation

- VISCOROL Series - Magnetic Level Indicators: DescriptionDocument4 pagesVISCOROL Series - Magnetic Level Indicators: DescriptionRaduPas encore d'évaluation

- Sciencedirect: Jad Imseitif, He Tang, Mike Smith Jad Imseitif, He Tang, Mike SmithDocument10 pagesSciencedirect: Jad Imseitif, He Tang, Mike Smith Jad Imseitif, He Tang, Mike SmithTushar singhPas encore d'évaluation

- ReviewerDocument2 pagesReviewerAra Mae Pandez HugoPas encore d'évaluation

- Different Software Life Cycle Models: Mini Project OnDocument11 pagesDifferent Software Life Cycle Models: Mini Project OnSagar MurtyPas encore d'évaluation

- 87 - Case Study On Multicomponent Distillation and Distillation Column SequencingDocument15 pages87 - Case Study On Multicomponent Distillation and Distillation Column SequencingFranklin Santiago Suclla Podesta50% (2)

- T3A-T3L Servo DriverDocument49 pagesT3A-T3L Servo DriverRodrigo Salazar71% (7)

- Rehabilitation and Retrofitting of Structurs Question PapersDocument4 pagesRehabilitation and Retrofitting of Structurs Question PapersYaswanthGorantlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Danh Sach Khach Hang VIP Diamond PlazaDocument9 pagesDanh Sach Khach Hang VIP Diamond PlazaHiệu chuẩn Hiệu chuẩnPas encore d'évaluation

- Bea Form 7 - Natg6 PMDocument2 pagesBea Form 7 - Natg6 PMgoeb72100% (1)

- Pro Tools ShortcutsDocument5 pagesPro Tools ShortcutsSteveJones100% (1)

- Canopy CountersuitDocument12 pagesCanopy CountersuitJohn ArchibaldPas encore d'évaluation

- Study of Risk Perception and Potfolio Management of Equity InvestorsDocument58 pagesStudy of Risk Perception and Potfolio Management of Equity InvestorsAqshay Bachhav100% (1)