Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Plastic Waste: A Local and Global Problem

Transféré par

Ali SirDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Plastic Waste: A Local and Global Problem

Transféré par

Ali SirDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Plastic waste: A local and global problem

By Marit Stinus-Cabugon

JANUARY is Zero Waste Month. The National Solid Waste Management Commission defines zero waste as an “advocacy that

promotes the designing and managing of products and processes to avoid and eliminate the volume and toxicity of waste and materials.”

To bring zero waste advocacy to a higher level, more than a thousand youth gathered in Dumaguete City to share best practices

from communities that are successfully working towards the zero waste goal. The event, dubbed 2018 Zero Waste Youth Convergence,

was hosted by the Foundation University College of Business Administration. The participants signed a petition addressed to Dumaguete

City Mayor Felipe Remollo urging him to implement a six-year-old city ordinance that bans plastic bags and styrofoam. The full

implementation of the ordinance, passed in August 2011, reportedly got stranded on businesses’ assurances that they were using

biodegradable plastics.

The ordinance was passed to address the clogging of creeks and canals, and to protect the environment and the public’s health.

That was 2011. Fast forward to 2018 and “Dumaguete City is facing a waste crisis,” to quote the Facebook-posted call for the youth to

join the zero-waste event and make a difference. “Our dumpsite is overfilled and waste from the dumpsite falls into the Banica River, our

beaches and parks are strewn with garbage, trash clogs our canals and estuaries, and plastic waste that will remain in the environment

for hundreds of years is spreading in our coastal waters including our marine protected areas.” Famous dive spot Apo Island is just a few

kilometers off the coast of Dumaguete City.

As to the allegedly biodegradable plastics, the European Union Commission in its “A European Strategy for Plastics in Circular

Economy” (January 16, 2018) points out that available biodegradable plastics mostly “degrade under very specific conditions which may

not always be easy to find in the natural environment, and can thus still cause harm to ecosystems.” Moreover, in the Philippine context,

plastic bags labeled biodegradable are actually not biodegradable but so-called oxo-degradable plastics. Such bags are worse than

traditional plastic bags in as much as they deteriorate and disintegrate into tiny pieces (microplastics) that can neither be reused nor

recycled. The EU Commission has “started work with the intention to restrict the use of oxo-plastics in the EU.”

The EU plastics strategy is part of its transition to a “Circular Economy” as it is a response to necessity. Like Dumaguete City,

the EU is facing a waste crisis. Starting this year, China has banned the importation of 24 categories of trash and has set strict standards

for the plastic waste that it will continue to import. In 2015 China imported 49.6 million tons of trash from mostly developed countries,

including the EU, the US, Japan and Australia. The EU generates about 26 million tons of plastic garbage every year of which more than

three million tons would be exported to China. Ships that bring Chinese-made consumer goods to Europe would return empty to China

if not for the trash that China’s recycling sector has been importing (AFP/Yahoo, January 21, 2018).

China’s ban is a wake-up call for developed countries to overhaul their waste management policies in general, and their plastics

policies in particular. Environmental organization GAIA in its “Recycling is Not Enough” report released a week ago, points out that rich

countries recycle “their own high-quality plastic domestically and export low-worth plastics to Asia.” Unfortunately, recycling businesses

that lost their market with China’s ban are now looking to other Asian countries. Rob Cole reports that Taiwan, Malaysia, Vietnam and

Turkey are already importing more waste from Europe since last year while Indonesia and Thailand are ‘new markets’ (www.resource.co,

January 9, 2018).

Another immediate effect of the ban is that more garbage is likely to end up in landfills and incinerators, including waste-to-

energy plants. Fortunately, the EU doesn’t see these as long-term solutions. With its new plastics strategy and in line with the Circular

Economy, the EU Commission is setting 2030 as deadline for all plastic packaging to be reusable or easily recyclable. China’s saying no

to being the receptacle of the world’s trash is the opportunity for the EU to be consistent in its environmental policies. We can’t just use

a lot of plastic, then export it and think that it will disappear, the EU ambassador to the Philippines, Franz Jessen, told the Kapihan sa

Manila Bay last January 24. This year, incidentally, the EU will launch a project in East and Southeast Asia to address these regions’

growing problems with plastic waste and marine litter.

Plastic might be the most significant invention since the invention of the wheel and the number zero. But today it’s choking us

and the world we live in. This is a global problem that we can’t export, burn or dump ourselves out of.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Cutting plastics pollution: Financial measures for a more circular value chainD'EverandCutting plastics pollution: Financial measures for a more circular value chainPas encore d'évaluation

- Students Will Show, Through A PPT Any Item, Its Plastic Packaging and Impact On Our LivesDocument9 pagesStudents Will Show, Through A PPT Any Item, Its Plastic Packaging and Impact On Our Livesnavya goyalPas encore d'évaluation

- Mare Plasticum - The Plastic Sea: Combatting Plastic Pollution Through Science and ArtD'EverandMare Plasticum - The Plastic Sea: Combatting Plastic Pollution Through Science and ArtMarilena Streit-BianchiPas encore d'évaluation

- We Can't Just Recycle Our Way Out of The Plastic Pollution CrisisDocument2 pagesWe Can't Just Recycle Our Way Out of The Plastic Pollution CrisisHamid Dewa ShaputraPas encore d'évaluation

- Marine Assignment 2 - Article ReviewDocument4 pagesMarine Assignment 2 - Article ReviewTerrie JohnnyPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastic Pollution: The Dark Side of Plastic ConsumptionD'EverandPlastic Pollution: The Dark Side of Plastic ConsumptionPas encore d'évaluation

- Recycling: Incentives For Plastic Recycling: How To Engage Citizens in Active Collection. Empirical Evidence From SpainDocument20 pagesRecycling: Incentives For Plastic Recycling: How To Engage Citizens in Active Collection. Empirical Evidence From SpainKislay KumudPas encore d'évaluation

- Bugen 3711 Ass 1 FullDocument8 pagesBugen 3711 Ass 1 Fullkwtee5430Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Ban On Plastic Bags in KenyaDocument4 pagesThe Ban On Plastic Bags in KenyaSheila ChumoPas encore d'évaluation

- Background: Not Only The Marine Ecosystem, It Also Affects Food Safety and Quality, Human Health, and Coastal TourismDocument2 pagesBackground: Not Only The Marine Ecosystem, It Also Affects Food Safety and Quality, Human Health, and Coastal TourismAdhilla SalsabilaPas encore d'évaluation

- UNEP - France - Adinda Putri MahindraDocument2 pagesUNEP - France - Adinda Putri MahindraAdhilla SalsabilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Santi's Project ReportDocument85 pagesSanti's Project ReportdamolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Prevention Is Crucial To Tackling Plastic Waste CrisisDocument4 pagesPrevention Is Crucial To Tackling Plastic Waste CrisisHiroshima MedonzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Marpol Commitments Web RevDocument10 pagesMarpol Commitments Web RevNofiliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research ProposalDocument15 pagesResearch ProposalPius VirtPas encore d'évaluation

- Briefing Eu LegislationDocument13 pagesBriefing Eu LegislationJosé PérezPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Menace of Plastic Waste in Nigeria ChallengesDocument12 pagesEnvironmental Menace of Plastic Waste in Nigeria ChallengesEdosael KefyalewPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastic StrategyDocument3 pagesPlastic StrategySafe FoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-692434042Pas encore d'évaluation

- Banning Straws and Bags WonDocument17 pagesBanning Straws and Bags WonDared KimPas encore d'évaluation

- A Plastic WorldDocument1 pageA Plastic Worldprincess sanaPas encore d'évaluation

- MPRA Paper 96263Document17 pagesMPRA Paper 96263Gohan SayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastics - The - Facts 2019Document42 pagesPlastics - The - Facts 2019Manuel Jiménez Díaz100% (1)

- Plastic Pollution - Tanya GuptaDocument20 pagesPlastic Pollution - Tanya GuptaTanya GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Concept PaperDocument11 pagesConcept PaperJinky Joy JessicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Usage of Single Use PlasticsDocument6 pagesUsage of Single Use Plasticsrafeek aadamPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Report Without Track ChangesDocument8 pagesFinal Report Without Track Changesapi-558671600Pas encore d'évaluation

- Matanglawin: The Philippines Growing Plastic ProblemDocument8 pagesMatanglawin: The Philippines Growing Plastic ProblemChelsea Marie CastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Case StudyDocument2 pagesCase StudyabhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Reducing Plastic BagsDocument2 pagesReducing Plastic BagsNancy DanielPas encore d'évaluation

- Roadmap Plastic SolutionDocument9 pagesRoadmap Plastic SolutionPeter CardenasPas encore d'évaluation

- Midterm AssignmentDocument1 pageMidterm AssignmentHồng NhungPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 1. Experimental Study of Plastic Bricks Made From WasteDocument27 pages1 1. Experimental Study of Plastic Bricks Made From WastePranay ManwarPas encore d'évaluation

- UNEP - Combatting Plastic PollutionDocument12 pagesUNEP - Combatting Plastic PollutionDhruv AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastic PollutionDocument29 pagesPlastic PollutionBrickPas encore d'évaluation

- UNEP Report On Single Use Plastic PDFDocument108 pagesUNEP Report On Single Use Plastic PDFAdrian JBrgPas encore d'évaluation

- Recycled MaterialsDocument8 pagesRecycled MaterialsJhing PacudanPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - © Nahin Ibn ZamanDocument36 pages1 - © Nahin Ibn ZamanNahin Ibn ZamanPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastics Ban and Its RecyclingDocument26 pagesPlastics Ban and Its RecyclingAlliedschool DefencecampusPas encore d'évaluation

- Sri Lanka (Single Use Plastic Waste)Document4 pagesSri Lanka (Single Use Plastic Waste)alyatashaPas encore d'évaluation

- Poster JRDocument1 pagePoster JRJosip RoncevicPas encore d'évaluation

- W3 Problem&SolutionDocument4 pagesW3 Problem&SolutionVito CorleonePas encore d'évaluation

- The State of Anti Plastic Campaign,' The Law, Its Effects and ImplementationDocument6 pagesThe State of Anti Plastic Campaign,' The Law, Its Effects and ImplementationBiren samal67% (3)

- Chemistry ProjectDocument10 pagesChemistry ProjectSahisa MahatPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastic UseDocument2 pagesPlastic UseMohit BharatiPas encore d'évaluation

- MathsDocument11 pagesMathsAAYUSHI VERMA 7APas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Law Rough NoteDocument10 pagesEnvironmental Law Rough NoteAbhijith AUPas encore d'évaluation

- Proj 201 Final Report - FUDocument15 pagesProj 201 Final Report - FUEce DemirbolatPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Essay Sarah MarellaDocument5 pagesLegal Essay Sarah MarellaSarah MarellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ab RproposalDocument11 pagesAb Rproposaleraidamae.saurePas encore d'évaluation

- Turning The TideDocument2 pagesTurning The Tidethekalyanche1Pas encore d'évaluation

- New Policy Framework With Plastic Waste Control Plan For E Ective Plastic Waste ManagementDocument14 pagesNew Policy Framework With Plastic Waste Control Plan For E Ective Plastic Waste Managementhaseeb ahmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Years To Collapse, Though The Complex Ones Take Between 100 and 600 Years or Even BeyondDocument3 pagesYears To Collapse, Though The Complex Ones Take Between 100 and 600 Years or Even BeyondWaleedPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Impacts of The Fashion IndustryDocument3 pagesEnvironmental Impacts of The Fashion Industryfadiyya kPas encore d'évaluation

- Single Use Plastic (SUP) Ban in India: Economy V. EnvironmentDocument14 pagesSingle Use Plastic (SUP) Ban in India: Economy V. EnvironmentRajni KumariPas encore d'évaluation

- Beach Bots, Sea Raptors' and Marine Toolsets Mobilised To Get Rid of Marine LitterDocument5 pagesBeach Bots, Sea Raptors' and Marine Toolsets Mobilised To Get Rid of Marine LitterConor McDonaghPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastic ContributionDocument2 pagesPlastic ContributionJayson baduyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Polymer Waste Civil 12Document65 pagesPolymer Waste Civil 12JAYAKRISHNAN M RPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastic Wasteland: Asia's Ocean Pollution Crisis: Tuesday, 05 Jun 2018Document4 pagesPlastic Wasteland: Asia's Ocean Pollution Crisis: Tuesday, 05 Jun 2018Im YunPas encore d'évaluation

- A Analogy TypesDocument3 pagesA Analogy TypesJuls100% (1)

- Ch11 NotesDocument3 pagesCh11 NotesAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Guidelines For Position PaperDocument2 pagesGuidelines For Position PaperAli Sir100% (1)

- My ProfitDocument4 pagesMy ProfitAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- ExperimentDocument6 pagesExperimentAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- A Analogy TypesDocument3 pagesA Analogy TypesJuls100% (1)

- Plastic Waste: A Local and Global ProblemDocument1 pagePlastic Waste: A Local and Global ProblemAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Contract TheoryDocument2 pagesSocial Contract TheoryAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Contract TheoryDocument2 pagesSocial Contract TheoryAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- (CHEM) Experiment GuidelinesDocument21 pages(CHEM) Experiment GuidelinesAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- ArticlesDocument7 pagesArticlesAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- E Math ReportingDocument24 pagesE Math ReportingAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastic Waste: A Local and Global ProblemDocument1 pagePlastic Waste: A Local and Global ProblemAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Euthanasia: Mercy KillingDocument4 pagesEuthanasia: Mercy KillingAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Cash Disbursements Cash Receipts JournalsDocument2 pagesCash Disbursements Cash Receipts JournalsAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Earth Science MineralsDocument2 pagesEarth Science MineralsAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre-Cal Shit First TakeDocument2 pagesPre-Cal Shit First TakeAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- It Is Made Up of IslandsDocument1 pageIt Is Made Up of IslandsAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Maurice Nicoll The Mark PDFDocument4 pagesMaurice Nicoll The Mark PDFErwin KroonPas encore d'évaluation

- Earth Science MineralsDocument2 pagesEarth Science MineralsAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- ToolsDocument29 pagesToolsAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- Research ProblemsDocument10 pagesResearch ProblemsAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- E Math ReportingDocument24 pagesE Math ReportingAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- The Circulatory System: 2 Divisions: Cardiovascular System Lymphatic SystemDocument20 pagesThe Circulatory System: 2 Divisions: Cardiovascular System Lymphatic SystemAli SirPas encore d'évaluation

- LCA Report Final CFGF - 29022012 PDFDocument42 pagesLCA Report Final CFGF - 29022012 PDFFelipe Ascencio FigueroaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fermentation of Sea Food Waste - A Novel Solution To Environmental ProblemDocument25 pagesFermentation of Sea Food Waste - A Novel Solution To Environmental ProblemHrudananda GochhayatPas encore d'évaluation

- CONCLUSION EnvDocument3 pagesCONCLUSION EnvNoor FatihahPas encore d'évaluation

- ACt 6Document6 pagesACt 6Joshua de JesusPas encore d'évaluation

- MSDS Hydrazine Hydrate 80Document12 pagesMSDS Hydrazine Hydrate 80Hanif DamayantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Salomone2016 PDFDocument39 pagesSalomone2016 PDFjocyeoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hysol EA934NA Part B 8OZ MSDSDocument5 pagesHysol EA934NA Part B 8OZ MSDSSEBASTIAN CARDONA QUIMBAYAPas encore d'évaluation

- ACR CleanUp DrivingDocument2 pagesACR CleanUp DrivingDale Marie Renomeron100% (1)

- Chemistry ReportDocument29 pagesChemistry ReportJenneth Cabinto DalisanPas encore d'évaluation

- Biogas Calculator TemplateDocument27 pagesBiogas Calculator TemplateAlex Julian-CooperPas encore d'évaluation

- Green Polymer Chemistry and Bio-Based Plastics - Dreams and RealityDocument16 pagesGreen Polymer Chemistry and Bio-Based Plastics - Dreams and RealityDIEGO ALONSO GOMEZ REYESPas encore d'évaluation

- A.1 Site Development Including Minor Excavation: Batching and Crushing PlantDocument4 pagesA.1 Site Development Including Minor Excavation: Batching and Crushing PlantJaja BarredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Waste Management ProcedureDocument3 pagesWaste Management ProcedureBoby ThomasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Green BuildingDocument16 pagesThe Green BuildingDeanPas encore d'évaluation

- Food Lab Safety ContractDocument3 pagesFood Lab Safety Contractapi-439595804Pas encore d'évaluation

- Godrej and Boyce Corporate ProfileDocument2 pagesGodrej and Boyce Corporate ProfileAyushi JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Hakan Tozan+Alper Erturk - Book - Applications of Contemporary Management Approaches in Supply Chains PDFDocument166 pagesHakan Tozan+Alper Erturk - Book - Applications of Contemporary Management Approaches in Supply Chains PDFJose LaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Tridol S3Document8 pagesTridol S3Jhamberti Miguel Vigil LeivaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3Document14 pagesChapter 3donna benitoPas encore d'évaluation

- NRP - Non Technical SummaryDocument30 pagesNRP - Non Technical Summaryvibin globalPas encore d'évaluation

- FOOD PROCESS Week 6 Conduct Work in Accordance With Environmental Policies and ProceduresDocument27 pagesFOOD PROCESS Week 6 Conduct Work in Accordance With Environmental Policies and ProceduresLEO CRISOSTOMOPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Notes 4Document214 pagesPersonal Notes 4ridhiPas encore d'évaluation

- RESEARCH - Waste ManagementDocument39 pagesRESEARCH - Waste ManagementBarista 2022Pas encore d'évaluation

- 01 Guidance On Iso 9001 2008 Sub-Clause 1.2 ApplicationDocument332 pages01 Guidance On Iso 9001 2008 Sub-Clause 1.2 ApplicationSyed Umair HashmiPas encore d'évaluation

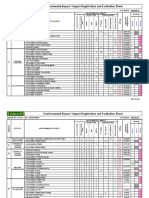

- Environmental Aspect / Impact Registration and Evaluation SheetDocument3 pagesEnvironmental Aspect / Impact Registration and Evaluation SheetrewrtegamingPas encore d'évaluation

- HSE Issues in The Petroleum IndustryDocument4 pagesHSE Issues in The Petroleum Industrycrtnngl0Pas encore d'évaluation

- NCM 104 Handout On EhsDocument5 pagesNCM 104 Handout On EhsJerah Aceron SatorrePas encore d'évaluation

- DSR Beed District 2015 2016Document253 pagesDSR Beed District 2015 2016ramprakashp100% (3)

- Tle-Agri Crop 2q-Week 3-Final (Waste Material Management)Document10 pagesTle-Agri Crop 2q-Week 3-Final (Waste Material Management)Mary Grace PesalboPas encore d'évaluation

- Health7 - q1 - Mod1 - Dimension of Holistic Health - FINAL08032020Document23 pagesHealth7 - q1 - Mod1 - Dimension of Holistic Health - FINAL08032020Mark Anthony Telan Pitogo100% (9)

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseD'EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (69)

- Alex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessD'EverandAlex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessPas encore d'évaluation

- World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other AstonishmentsD'EverandWorld of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other AstonishmentsÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (223)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingD'EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (33)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingD'EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)

- The Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsD'EverandThe Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (65)

- Fire Season: Field Notes from a Wilderness LookoutD'EverandFire Season: Field Notes from a Wilderness LookoutÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (142)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionD'EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (811)

- When the Sahara Was Green: How Our Greatest Desert Came to BeD'EverandWhen the Sahara Was Green: How Our Greatest Desert Came to BeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (6)

- Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldD'EverandWayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (18)

- The Best American Science And Nature Writing 2021D'EverandThe Best American Science And Nature Writing 2021Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (8)

- Why Fish Don't Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of LifeD'EverandWhy Fish Don't Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of LifeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (699)

- Come Back, Como: Winning the Heart of a Reluctant DogD'EverandCome Back, Como: Winning the Heart of a Reluctant DogÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (10)

- The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildD'EverandThe Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (44)

- The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldD'EverandThe Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (593)

- The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorD'EverandThe Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (137)

- When You Find Out the World Is Against You: And Other Funny Memories About Awful MomentsD'EverandWhen You Find Out the World Is Against You: And Other Funny Memories About Awful MomentsÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (13)

- Spoiled Rotten America: Outrages of Everyday LifeD'EverandSpoiled Rotten America: Outrages of Everyday LifeÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (19)

- The Big, Bad Book of Botany: The World's Most Fascinating FloraD'EverandThe Big, Bad Book of Botany: The World's Most Fascinating FloraÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (10)

- The Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanD'EverandThe Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They CommunicateD'EverandThe Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They CommunicateÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1002)