Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Effect of Pregnamcy On Adverse Outcomes

Transféré par

I Putu Adi PalgunaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Effect of Pregnamcy On Adverse Outcomes

Transféré par

I Putu Adi PalgunaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Research

Original Investigation

Effect of Pregnancy on Adverse Outcomes

After General Surgery

Hunter B. Moore, MD; Elizabeth Juarez-Colunga, PhD; Michael Bronsert, PhD, MS; Karl E. Hammermeister, MD;

William G. Henderson, MPH, PhD; Ernest E. Moore, MD; Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Supplemental content at

IMPORTANCE The literature regarding the occurrence of adverse outcomes following jamasurgery.com

nonobstetric surgery in pregnant compared with nonpregnant women has conflicting

findings. Those differing conclusions may be the result of inadequate adjustment for

differences between pregnant and nonpregnant women. It remains unclear whether

pregnancy is a risk factor for postoperative morbidity and mortality of the woman after

general surgery.

OBJECTIVE To compare the risk of postoperative complications in pregnant vs nonpregnant

women undergoing similar general surgical procedures.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS In this retrospective cohort study, data were obtained

from the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

participant user file from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2011. Propensity-matched

females based on 63 preoperative characteristics were matched 1:1 with nonpregnant women

undergoing the same operations by general surgeons. Operations performed between

January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2011, were analyzed for postoperative adverse events

occurring within 30 days of surgery.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Rates of 30-day postoperative mortality, overall morbidity,

and 21 individual postoperative complications were compared.

RESULTS The unmatched cohorts included 2764 pregnant women (50.5% underwent

emergency surgery) and 516 705 nonpregnant women (13.2% underwent emergency

surgery) undergoing general surgery. After propensity matching, there were no meaningful

differences in all 63 preoperative characteristics between 2539 pregnant and 2539

nonpregnant patients (all standardized differences, <0.1). The 30-day mortality rates were

similar (0.4% in pregnant women vs 0.3% in nonpregnant women; P = .82), and the rate of

overall morbidity was also not significantly different between pregnant vs nonpregnant

patients (6.6% vs 7.4%; P = .30).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE There was no significant difference in overall morbidity or

30-day mortality rates in pregnant and nonpregnant propensity-matched women undergoing

similar general surgical operations. General surgery appears to be as safe for pregnant women

as it is for nonpregnant women.

Author Affiliations: Author

affiliations are listed at the end of this

article.

Corresponding Author: Robert A.

Meguid, MD, MPH, Surgical

Outcomes and Applied Research

Program, Department of Surgery,

School of Medicine, University of

Colorado, Mail Stop C310, 12631 E

JAMA Surg. 2015;150(7):637-643. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.91 17th Ave, Aurora, CO 80045 (robert

Published online May 13, 2015. .meguid@ucdenver.edu).

(Reprinted) 637

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 01/12/2018

Research Original Investigation Effect of Pregnancy on Adverse Outcomes After General Surgery

H

istorical data1 suggest that 1 in 500 pregnant patients ACS NSQIP perioperative complications) occurring within 30

require nonobstetric surgery. Pregnancy is associ- days of the index operation. These complications included

ated with physiologic changes in body habitus and the acute renal failure requiring dialysis or hemofiltration; pro-

coagulation,2 cardiovascular,3 pulmonary,4 and immune5 sys- gressive renal insufficiency; bleeding requiring transfusion of

tems. These changes pose a diagnostic and treatment chal- more than 4 U of packed red blood cells; cardiac arrest requir-

lenge to surgeons because physical examination findings and ing cardiopulmonary resuscitation; Q-wave myocardial infarc-

laboratory test values are different from those routinely tion; deep venous thrombosis or thrombophlebitis requiring

encountered.6,7 Therefore, it might be expected that postop- treatment; pulmonary embolism; pneumonia; prolonged (>48

erative complications in pregnant patients are increased com- hours) intubation; unplanned intubation; septic shock; cere-

pared with those in nonpregnant patients. Several retrospec- brovascular accident (including trauma such as a fall, result-

tive studies8,9 have supported this hypothesis. However, ing in an injury to the head) or stroke with subsequent neu-

equivalent complication rates between pregnant and nonpreg- rologic deficit; sepsis; superficial surgical site infection; deep

nant patients have also been reported.10,11 Review of these dis- incisional surgical site infection; organ or organ space surgi-

parate studies suggests that the heterogeneity of outcomes is cal site infection; urinary tract infection; wound disruption;

likely the result of differences in the types of operations stud- peripheral nerve injury; graft, prosthesis, or flap failure; and

ied and the inability to account for differences in patient char- coma lasting longer than 24 hours.13

acteristics of pregnant and nonpregnant women in the statis-

tical analyses. Statistical Analysis

Although several investigators9-11 report that they have ad- Differences between pregnant and nonpregnant patients were

justed for differences in patient baseline characteristics, none compared with χ2 tests for categorical variables and 2-tailed

of these studies has attempted to do this using propensity independent t tests for continuous variables in the un-

matching. Because pregnancy usually occurs in younger matched cohorts. Differences between the groups were also

women as well as considering the broad alterations across the evaluated using the standardized differences14 to enable com-

body’s physiology as a result of pregnancy, we anticipated dif- parison of covariate imbalance between the matched and un-

ferences in preoperative characteristics between nonpreg- matched cohorts. The absolute value of the standard differ-

nant and pregnant patients. Therefore, we used propensity ence of less than 0.1 indicates that the groups are well balanced

matching, a technique recommended12 for comparison of for that characteristic; differences greater than 0.1 or less than

groups of interest with low event rates. −0.1 indicate some imbalance. The McNemar test, either in its

Using the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgi- large sample size approximation or exact form, was used to

cal Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) participant use compare 30-day mortality and morbidity in the propensity-

file (PUF), we evaluated adverse operative outcome rates in matched cohorts.

general surgery contrasting pregnant with propensity- Propensity-score matching methods were used to reduce

matched nonpregnant women. We hypothesized that preg- confounding related to nonrandom assignment of pregnancy.15

nant women are at greater risk of complications than are com- A propensity score is the predicted probability, based on lo-

parable nonpregnant women undergoing similar general gistic regression, that a given woman will be pregnant. This ap-

surgical operations. proach was used because of its performance and simplicity.

Pregnant patients were propensity matched 1:1 to controls with

a greedy algorithm.16 The propensity score logit model in-

cluded 63 patient preoperative characteristics.

Methods Despite the large sample of nonpregnant women, we con-

Study Design and Population ducted one-to-one matching to avoid the possible bias of many-

This retrospective cohort study compared 30-day postopera- to-one matching.17 Each pregnant patient was matched to a

tive surgical outcomes of pregnant vs nonpregnant women un- single nonpregnant control patient if her predicted propen-

dergoing nonobstetric operations by general surgeons. Pa- sity scores were identical to 8 decimal places. If such a match

tients were identified from the ACS NSQIP PUF, a database of was not found, the pregnant patient was matched to a non-

surgical procedures performed in hospitals participating in the pregnant patient on the basis of a 7–, 6–, 5–, 4–, 3–, 2–, or 1–deci-

ACS NSQIP from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2011. Pa- mal place match, tested sequentially. Missing values were

tients were excluded if they were male, underwent obstetric treated as a separate category for the categorical variables of

surgery, or were missing one or more of the preoperative pa- race/ethnicity, body mass index, and the 12 preoperative labo-

tient characteristics used in the study. Nonpregnant women ratory test values. Laboratory test values were coded as miss-

were also excluded if they underwent operations that were not ing, abnormal low, normal, and abnormal high according to val-

performed in the group of pregnant patients. The Colorado Mul- ues presented in a widely used medical textbook.18

tiple Institutional Review Board classified this study as not in- Differences in complications and mortality rates were also

volving human subject research. analyzed in subgroups of emergency and nonemergency op-

erations. To retain high power, we included an interaction term

Primary Outcome for pregnancy and emergency in a conditional logistic regres-

The primary outcome variables for the analyses in this study sion model. Evidence of an interaction would indicate that the

were death from any cause and overall morbidity (≥1 of the 21 association between pregnancy and complication rates was dif-

638 JAMA Surgery July 2015 Volume 150, Number 7 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 01/12/2018

Effect of Pregnancy on Adverse Outcomes After General Surgery Original Investigation Research

Figure 1. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Flow Diagram of Pregnant vs Nonpregnant Women

Undergoing the Same General Surgical Operations

651 594 Women undergoing general

surgery in the ACS NSQIP

dataset, 2006-2011

49 977 Missing ≥1 preoperative Yes Preoperative risk factors No 601 617 No preoperative risk factor

risk factor missing? missing

Yes No

2011 Obstetric/gynecologic surgery Obstetric/gynecologic surgery? 599 606 No obstetric/gynecologic surgery

No Yes

596 842 Nonpregnant women Pregnant?

Same CPT code as Yes

pregnant patient?

No

80 137 Nonpregnant women with 516 705 Nonpregnant women with 2764 Pregnant women undergoing

other CPT codes same CPT codes surgery

2539 Matched nonpregnant women 2539 Matched pregnant women

Data were obtained from the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) (2006-2011). CPT indicates Current

Procedural Terminology.

ferent in emergency vs nonemergency cases. The a priori level The standardized differences for the proportions or means

of statistical significance was set at α = .05 for all analyses, between the pregnant and nonpregnant unmatched cohorts

which were 2-tailed. Statistical analyses were performed with are reported in eTable 1 in the Supplement. The standardized

SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). differences were greater than 0.1 or less than −0.1 for 31 of the

63 preoperative patient characteristics (49.2%), indicating the

expected, important imbalances between pregnant and non-

pregnant patients in the unmatched cohorts.

Results In the unmatched cohort, 10 of 2764 pregnant patients

There were 651 594 adult women undergoing operations by (0.4%) died within 30 days of surgery compared with 5759 of

general surgeons in the ACS NSQIP PUF from 2006 to 2011. Ex- 516 705 nonpregnant patients (1.1%) (P < .001) (Table). The

clusion criteria and sample size of patients in this analysis are overall morbidity rate was also lower for pregnant patients (183/

demonstrated in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observa- 2764 [6.6%] vs 48 394/516 705 [9.4%]; P < .001) than nonpreg-

tional Studies in Epidemiology diagram (Figure 1). Of the nant patients. Pregnant patients had significantly lower rates

651 594 patients, 49 977 (7.7%) were excluded because they of superficial surgical site infection, urinary tract infection,

were missing 1 or more preoperative patient characteristic, and bleeding requiring transfusion of more than 4 U of packed red

2011 patients (0.3%) were excluded because they underwent blood cells, myocardial infarction, and unplanned intubation

an obstetric operation. An additional 80 137 nonpregnant pa- compared with nonpregnant patients in the unmatched co-

tients (12.3%) were excluded because they underwent an op- hort (P value range, .005-.049).

eration that was not performed in the group of pregnant pa- The propensity model is provided in eTable 2 in the Supple-

tients. A total of 519 469 patients remained: 2764 (0.5%) were ment. Thirty-seven of the preoperative patient characteristics

pregnant and 516 705 (99.5%) were nonpregnant. were significant predictors of pregnancy, with the C statistic for

Characteristics of unmatched pregnant patients and non- the full model of 0.939. A total of 2539 of the 2764 pregnant pa-

pregnant patients are presented in eTable 1 in the Supple- tients (91.9%) were matched to 2539 of 516 705 (0.5%) nonpreg-

ment. The unmatched pregnant patients were significantly nant patients. The standardized differences in baseline charac-

younger than the nonpregnant patients (29.8 vs 53.0 years; teristics between the groups before and after matching on the

P < .001). Compared with the nonpregnant patients, the preg- propensity score are shown in Figure 2. In the propensity-

nant women were more likely to undergo surgery as an inpa- matched cohort, none of the 63 patient characteristics had stan-

tient (2074 [75.0%] vs 308 375 [59.7%]; P < .001) and undergo dardized differences greater than 0.1 or less than −0.1, indicat-

an emergency operation (1396 [50.5%] vs 68 156 [13.2%]; ing that the propensity-matched samples were well balanced.

P < .001). Pregnant patients generally had lower rates of pre- As reported in the Table for the propensity-matched co-

operative comorbidities but higher rates of abnormal labora- hort, there was no significant difference in the 30-day mor-

tory test results (high white blood cell count and low blood urea tality rates between pregnant and nonpregnant patients (0.4%

nitrogen, hematocrit, serum crell atinine, serum sodium, and vs 0.3%; P = .82) or in the overall morbidity rate in the preg-

serum albumin levels) compared with nonpregnant patients. nant patients vs nonpregnant women (6.6% vs 7.4%; P = .30).

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery July 2015 Volume 150, Number 7 639

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 01/12/2018

Research Original Investigation Effect of Pregnancy on Adverse Outcomes After General Surgery

Table. Bivariable Association of Complications With Pregnancy in the Unmatched and Matched Cohorts

No. (%)

Unmatched Matched

Complication Nonpregnant Pregnant P Value Nonpregnant Pregnant P Value

No. (%) 516 705 (99.5) 2764 (0.5) 2539 (4.9) 2539 (91.9)

Infection

Superficial surgical site infection 12 975 (2.5) 46 (1.7) .005 44 (1.7) 36 (1.4) .43

Sepsis 7854 (1.5) 36 (1.3) .35 38 (1.5) 35 (1.4) .82

Urinary tract infection 8169 (1.6) 28 (1.0) .02 29 (1.1) 27 (1.1) .89

Organ/organ space surgical site infection 6072 (1.2) 30 (1.1) .66 42 (1.7) 29 (1.1) .15

Deep incisional surgical site infection 3246 (0.6) 14 (0.5) .42 13 (0.5) 14 (0.6) >.99

Wound disruption 2133 (0.4) 11 (0.4) .90 6 (0.2) 9 (0.4) .61

Cardiac

Bleeding requiring transfusion of >4 U of PRBCs 7345 (1.4) 27 (1.0) .049 19 (0.8) 26 (1.0) .37

Cardiac arrest requiring CPR 1291 (0.2) 2 (0.1) .06 1 (0.04) 2 (0.1) >.99

Q-wave MI 901 (0.2) 0 .03 1 (0.04) 0 NA

Respiratory

Prolonged intubation (>48 h) 8002 (1.5) 35 (1.3) .23 28 (1.1) 35 (1.4) .44

Pneumonia 5340 (1.0) 22 (0.8) .22 14 (0.6) 21 (0.8) .30

Unplanned intubation 4886 (0.9) 13 (0.5) .01 11 (0.4) 13 (0.5) .84

Septic shock 4276 (0.8) 14 (0.5) .06 17 (0.7) 14 (0.6) .72

Venous thromboembolism

Deep venous thrombosis/thrombophlebitis 2617 (0.5) 10 (0.4) .29 6 (0.2) 10 (0.4) .45

Pulmonary embolism 1366 (0.3) 7 (0.3) .91 1 (0.04) 7 (0.3) .07

Renal

Acute renal failure requiring dialysis or hemofiltration 1353 (0.3) 4 (0.1) .23 3 (0.1) 4 (0.2) >.99

Progressive renal insufficiencya 1016 (0.2) 3 (0.1) .30 2 (0.1) 3 (0.1) >.99

Stroke

Stroke/cerebrovascular accident with neurologic deficit 621 (0.1) 0 .07 3 (0.1) 0 NA

Other NA

Peripheral nerve injury 162 (0.03) 0 .35 1 (0.04) 0 NA

Graft/prosthesis/flap failure 337 (0.1) 0 .18 1 (0.04) 0 NA

Coma for >24 h 255 (0.05) 0 .24 0 0

30-d Mortality 5759 (1.1) 10 (0.4) <.001 8 (0.3) 10 (0.4) .82

≥1 Complication 48 394 (9.4) 183 (6.6) <.001 188 (7.4) 168 (6.6) .30

Abbreviations: CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not available; PRBCs, packed red blood cells.

a

Progression was indicated by an increase in creatinine of more than 2 mg/dL from the preoperative value. To convert creatinine to micromoles per liter,

multiply by 88.4.

No significant differences were found when we compared the operative risk factors than nonpregnant women: the pregnant

rates of the 21 individual complications in the pregnant vs non- women were younger, had fewer comorbidities, and more fre-

pregnant patients after propensity matching. There was no evi- quently had abnormal laboratory test values. Pregnant women

dence of a different association between pregnancy and over- were also more likely to undergo emergency procedures. Un-

all morbidity or mortality rates in the emergency and balanced preoperative risk factors between the groups were

nonemergency subgroups (interaction P values: overall mor- balanced after propensity matching, thereby minimizing bias

bidity, P = .11; mortality, P = .74). in comparison of outcomes between the 2 patient popula-

tions. Analysis of matched cohorts showed no significant dif-

ferences in 30-day mortality or the occurrence of 1 or more com-

plications between the groups. Nonobstetric general surgery

Discussion appears to be as safe in pregnant women as in nonpregnant

We performed an analysis of pregnant women matched to non- women.

pregnant women undergoing general surgical operations using Prior studies reporting increased complication rates in

the ACS NSQIP PUF to determine whether pregnancy was as- pregnant vs nonpregnant women undergoing nonobstetric sur-

sociated with an increased rate of postoperative adverse out- gery come from analysis of the Health Care Utilization Proj-

comes. We observed that pregnant patients had different pre- ect Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Kuy et al9 reported in-

640 JAMA Surgery July 2015 Volume 150, Number 7 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 01/12/2018

Effect of Pregnancy on Adverse Outcomes After General Surgery Original Investigation Research

Figure 2. Standardized Differences in Population Baseline Characteristics in Pregnant vs Nonpregnant Women

Undergoing the Same General Surgical Operations Before and After Matching

Age, y Before matching

Race/ethnicity

After matching

Body mass index category

Work relative value unit

Inpatient/outpatient operation

Admitted directly from home

Emergency operation

Laparoscopic procedure

ASA class

Procedure category

Year of operation

Diabetes mellitus

Cigarette smoker (within 1 y)

>2 Alcoholic drinks/d (within 2 wk)

Dyspnea (within 30 d)

DNR order signed (within 30 d)

Functional health status prior to surgery

Ventilator dependent (within 48 h)

Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Pneumonia entering surgery

Ascites (within 30 d)

Esophageal varices (within 6 mo)

Congestive heart failure (within 30 d)

Myocardial infarction (within 6 mo)

Percutaneous coronary intervention

Major cardiac surgery

Angina (within 30 d)

BP >140/90 mm Hg or taking antihypertension medications

Revascularization or amputation for peripheral vascular disease

Rest pain or gangrene due to ischemia

Acute renal failure (rising creatinine to >3 mg/dL within 24 h)

Dialysis or hemofiltration (within 2 wk)

Impaired sensorium in context of current illness (within 48 h)

Coma entering surgery

Hemiplegia/hemiparesis

Transient ischemic attack

CVA/stroke with residual neurologic deficit

CVA/stroke without neurologic deficit

Tumor involving CNS

Paraplegia/paraparesis

Quadriplegia/quadriparesis

Disseminated cancer

Open wound with or without infection

Corticosteroid use for chronic condition

>10% Loss of body weight (within 6 mo)

Bleeding disorder requiring hospitalization

Transfusion within 72 h

Chemotherapy for cancer (within 30 d)

Radiation therapy for cancer (within 90 d)

Systemic sepsis (within 48 h)

Prior operation (within 30 d)

Preoperative serum sodium

Preoperative blood urea nitrogen

Preoperative serum creatinine

Preoperative serum albumin To convert creatinine to micromoles

Preoperative total bilirubin

per liter, multiply by 88.4. Solid

Preoperative AST level

vertical line indicates 0, dashed lines,

Preoperative alkaline phosphatase

Preoperative white blood cell count

0.1 and −0.1. ASA indicates American

Preoperative platelet count Association of Anesthesiologists;

Preoperative hematocrit AST, aspartate aminotransferase;

Preoperative partial thromboplastin time BP, blood pressure; CNS, central

Preoperative INR or PT value nervous system;

CVA, cerebrovascular accident;

–2.0 –1.5 –1.0 –0.5 0 0.5 1.0 1.5 DNR, do not resuscitate;

Standardized Difference INR, international normalized ratio;

and PT, prothrombin time.

creased rates of complications, length of stay, and cost for nant women undergoing cholecystectomy. Prior to regres-

pregnant women undergoing thyroid and parathyroid sur- sion analysis, the pregnant patients had an increased compli-

gery despite risk adjustment with logistic regression analysis cation rate. However, after age and procedure matching, as well

for the dichotomous outcome (complications) and linear re- as adjustment for insurance, race, and surgeon case volume,

gression for the continuous variables (length of stay and cost). pregnancy was not associated with an increased risk of surgi-

Using a similar time period, the same group11 evaluated preg- cal complications. A recent publication8 using the Health Care

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery July 2015 Volume 150, Number 7 641

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 01/12/2018

Research Original Investigation Effect of Pregnancy on Adverse Outcomes After General Surgery

Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample reported that the value of 1.0 for a perfect model. This finding supports the

postoperative complication rates following appendectomy conclusion that we have developed a reasonable model to pre-

were higher in pregnant vs nonpregnant women. In that study, dict pregnancy based on preoperative characteristics. The

Abbasi et al8 matched more than 7000 pregnant women to model eliminated measured, unbalanced preoperative vari-

35 000 nonpregnant women based on age and then per- ables quantified by standardized differences (Figure 2), and out-

formed multivariable logistic regression on categories of race, comes were appropriately assessed with a paired analysis con-

obesity, income, and insurance type. Although postoperative trasting pregnant to nonpregnant women. Other approaches,

complication rates were higher in the pregnant group, the most such as double robust inverse probability weighting, requir-

notable finding was that peritonitis on presentation was the ing specification of an outcomes regression model would not

highest predictor of postoperative complication rates. This have been a feasible approach with these data given the small

study identified that pregnant women more frequently present number of outcome events.12

with peritonitis than do nonpregnant women. The authors con- This study has strengths and limitations. Strengths in-

cluded that this factor was the causality for this discrepancy clude (1) a large sample from a broad range of hospitals, (2) a

between the groups. broad range of operations included in the database using a sys-

In contrast, some studies report low postoperative com- tematic sampling method, and (3) a standardized protocol for

plication rates in pregnant patients. Erekson et al19 analyzed collection of the ACS NSQIP PUF, with central auditing of the

the ACS NSQIP PUF. Their descriptive findings parallel our re- data. The primary limitations of this study include (1) the ob-

sults of low maternal postoperative complication rates, but they servational design so that only association (ie, not causation)

did not contrast pregnant and nonpregnant women. Silvestri may be concluded and (2) a lack of data on fetal outcomes.

et al10 found a similar rate of morbidity between pregnant and There is clearly a risk to the fetus when a pregnant woman un-

nonpregnant women undergoing cholecystectomy and ap- dergoes surgery. Fetal loss after appendectomy was found to

pendectomy. McMaster et al20 also found that pregnant pa- be 4% in women with a normal appendix.23 The increasing

tients had postoperative complication rates similar to those of number of reports indicates that infectious surgical indica-

nonpregnant women after breast surgery. tions, such as appendicitis and cholecystitis, are associated with

Because a prospective randomized clinical trial to iden- an unfavorable outcome for the fetus24,25 and that advanced

tify whether pregnancy is a risk factor for postoperative disease is a risk factor for fetal and maternal complications.23,26

complications is not feasible, only observational studies are Attempting medical management of surgical diseases (eg, ap-

available. The latter are dependent upon statistical adjust- pendicitis and cholecystitis) is associated with a worse out-

ment to account for significant baseline differences between come compared with early operative management.8,11 There-

pregnant and nonpregnant patients. The ACS NQIP PUF dur- fore, the well-being of the fetus represents an additional

ing our study time frame contained data on more than risk-benefit factor to consider in pregnant women, and an un-

500 000 nonpregnant women undergoing operations similar clear diagnosis may require further expeditious evaluation to

to those of pregnant patients. Propensity matching is well minimize delay of definitive management.

suited for this type of observational study in which a “large

reservoir” of potential controls is contrasted to a moderately

sized group.21 Propensity matching controls for measured

baseline covariates before analysis of the outcomes.22 This

Conclusions

technique does not require the complexity of forming mul- Pregnant patients undergoing emergency and nonemer-

tiple strata to balance covariates and is superior in reducing gency general surgery do not appear to have elevated rates of

bias.12 Propensity matching is used frequently in medical mortality or morbidity. We did not account for fetal compli-

studies because of its simplicity and robust performance, cations in this study and would not advocate that our find-

but it is not always reported appropriately.15 Key elements of ings be generalized to elective surgical situations that can be

propensity modeling that are often neglected include report- postponed until after delivery. Therefore, general surgery ap-

ing the model construct, assessment of prematching and pears to be as safe in pregnant as it is in nonpregnant women.

postmatching differences between groups, and appropriate These findings support previous reports that pregnant pa-

outcome analysis. tients who present with acute surgical diseases should un-

In our study, the maximum C statistic for the propensity dergo the procedure if delay in definitive care will lead to pro-

model was 0.939 (eTable 2 in the Supplement) compared with gression of disease.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Colunga, Bronsert, Hammermeister, Henderson, Department of Surgery, Denver Health Medical

Accepted for Publication: December 1, 2014. Meguid); Adult and Child Center for Health Center, Denver, Colorado (E. E. Moore).

Outcomes Research and Delivery Science, School of Author Contributions: Drs H. B. Moore and Juarez-

Published Online: May 13, 2015. Medicine, University of Colorado, Aurora (Juarez-

doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.91. Colunga had full access to all the data in the study

Colunga, Bronsert, Hammermeister, Henderson); and take responsibility for the integrity of the data

Author Affiliations: Department of Surgery, School Department of Biostatistics and Informatics, and the accuracy of the data analysis.

of Medicine, University of Colorado, Aurora Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora (Juarez- Study concept and design: H. B. Moore,

(H. B. Moore, E. E. Moore, Meguid); Surgical Colunga, Henderson); Division of Cardiology, Hammermeister, Henderson, Meguid.

Outcomes and Applied Research Program, School Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All

of Medicine, University of Colorado, Aurora (Juarez- University of Colorado, Aurora (Hammermeister); authors.

642 JAMA Surgery July 2015 Volume 150, Number 7 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 01/12/2018

Effect of Pregnancy on Adverse Outcomes After General Surgery Original Investigation Research

Drafting of the manuscript: H. B. Moore, 7. Augustin G, Majerovic M. Non-obstetrical acute each treated subject when using many-to-one

Juarez-Colunga, Hammermeister, E. E. Moore, abdomen during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol matching on the propensity score. Am J Epidemiol.

Meguid. Reprod Biol. 2007;131(1):4-12. 2010;172(9):1092-1097.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important 8. Abbasi N, Patenaude V, Abenhaim HA. 18. Kratz A, Pesce MA, Basner RC. Laboratory

intellectual content: All authors. Management and outcomes of acute appendicitis in values of clinical importance. In: Longo DL, Fauci

Statistical analysis: Juarez-Colunga, Bronsert, pregnancy–population-based study of over 7000 AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J,

Henderson, Meguid. cases. BJOG. 2014;121(12):1509-1514. eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th

Obtained funding: Meguid. ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012:appendix.

Administrative, technical, or material support: 9. Kuy S, Roman SA, Desai R, Sosa JA. Outcomes

E. E. Moore, Meguid. following thyroid and parathyroid surgery in 19. Erekson EA, Brousseau EC, Dick-Biascoechea

Study supervision: Hammermeister, Henderson, pregnant women. Arch Surg. 2009;144(5):399-406. MA, Ciarleglio MM, Lockwood CJ, Pettker CM.

E. E. Moore, Meguid. 10. Silvestri MT, Pettker CM, Brousseau EC, Dick Maternal postoperative complications after

MA, Ciarleglio MM, Erekson EA. Morbidity of nonobstetric antenatal surgery. J Matern Fetal

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported. Neonatal Med. 2012;25(12):2639-2644.

appendectomy and cholecystectomy in pregnant

Funding/Support: This project was supported by and nonpregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118 20. McMaster J, Dua A, Desai SS, Kuy S, Kuy S.

funding from the Department of Surgery, Adult and (6):1261-1270. Short term outcomes following breast cancer

Child Center for Health Outcomes Research and surgery in pregnant women. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;

Delivery Science Joint Surgical Outcomes and 11. Kuy S, Roman SA, Desai R, Sosa JA. Outcomes

following cholecystectomy in pregnant and 135(3):539-541.

Applied Research Program at the University of

Colorado. nonpregnant women. Surgery. 2009;146(2):358- 21. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of

366. the propensity score in observational studies for

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding sources causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41-44.

had no role in the design and conduct of the study; 12. Cepeda MS, Boston R, Farrar JT, Strom BL.

collection, management, analysis, and Optimal matching with a variable number of 22. Rubin DB. The design versus the analysis of

interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or controls vs a fixed number of controls for a cohort observational studies for causal effects: parallels

approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit study: trade-offs. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(3):230- with the design of randomized trials. Stat Med.

the manuscript for publication. 237. 2007;26(1):20-36.

13. Cohen ME, Ko CY, Bilimoria KY, et al. Optimizing 23. McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Tillou A, Hiatt JR,

REFERENCES ACS NSQIP modeling for evaluation of surgical Ko CY, Cryer HM. Negative appendectomy in

1. Kammerer WS. Nonobstetric surgery during quality and risk: patient risk adjustment, procedure pregnant women is associated with a substantial

pregnancy. Med Clin North Am. 1979;63(6):1157-1164. mix adjustment, shrinkage adjustment, and surgical risk of fetal loss. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(4):534-

focus. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(2):336-346.e1. 540.

2. Della Rocca G, Dogareschi T, Cecconet T, et al.

Coagulation assessment in normal pregnancy: 14. Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing 24. Wei PL, Keller JJ, Liang HH, Lin HC. Acute

thrombelastography with citrated non activated the distribution of baseline covariates between appendicitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes:

samples. Minerva Anestesiol. 2012;78(12):1357-1364. treatment groups in propensity-score matched a nationwide population-based study. J Gastrointest

samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083-3107. Surg. 2012;16(6):1204-1211.

3. Ouzounian JG, Elkayam U. Physiologic changes

during normal pregnancy and delivery. Cardiol Clin. 15. Austin PC. A critical appraisal of 25. Swisher SG, Schmit PJ, Hunt KK, et al. Biliary

2012;30(3):317-329. propensity-score matching in the medical literature disease during pregnancy. Am J Surg. 1994;168(6):

between 1996 and 2003. Stat Med. 2008;27(12): 576-579.

4. Orzechowski KM, Miller RC. Common 2037-2049.

respiratory issues in ambulatory obstetrics. Clin 26. Mourad J, Elliott JP, Erickson L, Lisboa L.

Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(3):798-809. 16. Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for Appendicitis in pregnancy: new information that

matching on the propensity score. Stat Med. 2014; contradicts long-held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet

5. Munoz-Suano A, Hamilton AB, Betz AG. Gimme 33(6):1057-1069. Gynecol. 2000;182(5):1027-1029.

shelter: the immune system during pregnancy.

Immunol Rev. 2011;241(1):20-38. 17. Austin PC. Statistical criteria for selecting the

optimal number of untreated subjects matched to

6. Coleman MT, Trianfo VA, Rund DA. Nonobstetric

emergencies in pregnancy: trauma and surgical

conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(3):497-

502.

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery July 2015 Volume 150, Number 7 643

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 01/12/2018

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- What Says Doctors About Kangen WaterDocument13 pagesWhat Says Doctors About Kangen Waterapi-342751921100% (2)

- Vocations The New Midheaven Extension ProcessDocument266 pagesVocations The New Midheaven Extension ProcessMiss M.100% (24)

- Sample Cross-Complaint For Indemnity For CaliforniaDocument4 pagesSample Cross-Complaint For Indemnity For CaliforniaStan Burman75% (8)

- Mixing and Agitation 93851 - 10 ADocument19 pagesMixing and Agitation 93851 - 10 Aakarcz6731Pas encore d'évaluation

- Digital SLR AstrophotographyDocument366 pagesDigital SLR AstrophotographyPier Paolo GiacomoniPas encore d'évaluation

- BECIL Registration Portal: How To ApplyDocument2 pagesBECIL Registration Portal: How To ApplySoul BeatsPas encore d'évaluation

- ICD10WHO2007 TnI4Document1 656 pagesICD10WHO2007 TnI4Kanok SongprapaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab 2 - Using Wireshark To Examine A UDP DNS Capture Nikola JagustinDocument6 pagesLab 2 - Using Wireshark To Examine A UDP DNS Capture Nikola Jagustinpoiuytrewq lkjhgfdsaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cad Data Exchange StandardsDocument16 pagesCad Data Exchange StandardskannanvikneshPas encore d'évaluation

- Mitsubishi FanDocument2 pagesMitsubishi FanKyaw ZawPas encore d'évaluation

- Audi R8 Advert Analysis by Masum Ahmed 10PDocument2 pagesAudi R8 Advert Analysis by Masum Ahmed 10PMasum95Pas encore d'évaluation

- Countable 3Document2 pagesCountable 3Pio Sulca Tapahuasco100% (1)

- Frequency Response For Control System Analysis - GATE Study Material in PDFDocument7 pagesFrequency Response For Control System Analysis - GATE Study Material in PDFNarendra AgrawalPas encore d'évaluation

- Jayesh PresentationDocument22 pagesJayesh PresentationanakinpowersPas encore d'évaluation

- Lect.1-Investments Background & IssuesDocument44 pagesLect.1-Investments Background & IssuesAbu BakarPas encore d'évaluation

- A SURVEY OF ENVIRONMENTAL REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MIDGE (Diptera: Tendipedidae)Document15 pagesA SURVEY OF ENVIRONMENTAL REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MIDGE (Diptera: Tendipedidae)Batuhan ElçinPas encore d'évaluation

- Microeconomics Term 1 SlidesDocument494 pagesMicroeconomics Term 1 SlidesSidra BhattiPas encore d'évaluation

- Teks Drama Malin KundangDocument8 pagesTeks Drama Malin KundangUhuy ManiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mule 4 Error Handling DemystifiedDocument8 pagesMule 4 Error Handling DemystifiedNicolas boulangerPas encore d'évaluation

- Addition Color by Code: Yellow 1, 2, Blue 3, 4, Pink 5, 6 Peach 7, 8 Light Green 9, 10, Black 11Document1 pageAddition Color by Code: Yellow 1, 2, Blue 3, 4, Pink 5, 6 Peach 7, 8 Light Green 9, 10, Black 11Noor NadhirahPas encore d'évaluation

- Part Time Civil SyllabusDocument67 pagesPart Time Civil SyllabusEr Govind Singh ChauhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Will Smith BiographyDocument11 pagesWill Smith Biographyjhonatan100% (1)

- Dissertation 7 HeraldDocument3 pagesDissertation 7 HeraldNaison Shingirai PfavayiPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan SustainabilityDocument5 pagesLesson Plan Sustainabilityapi-501066857Pas encore d'évaluation

- FAO-Assessment of Freshwater Fish Seed Resources For Sistainable AquacultureDocument669 pagesFAO-Assessment of Freshwater Fish Seed Resources For Sistainable AquacultureCIO-CIO100% (2)

- Applied Physics (PHY-102) Course OutlineDocument3 pagesApplied Physics (PHY-102) Course OutlineMuhammad RafayPas encore d'évaluation

- Terminal Blocks: Assembled Terminal Block and SeriesDocument2 pagesTerminal Blocks: Assembled Terminal Block and SeriesQuan Nguyen ThePas encore d'évaluation

- Redirection & PipingDocument16 pagesRedirection & PipingPraveen PatelPas encore d'évaluation

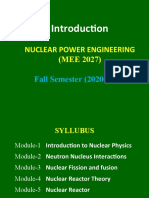

- Nuclear Power Engineering (MEE 2027) : Fall Semester (2020-2021)Document13 pagesNuclear Power Engineering (MEE 2027) : Fall Semester (2020-2021)AllPas encore d'évaluation

- IIM L: 111iiiiiiiDocument54 pagesIIM L: 111iiiiiiiJavier GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation