Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Building On What Is Already There - Int JNL 2012

Transféré par

lfbbarrosDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Building On What Is Already There - Int JNL 2012

Transféré par

lfbbarrosDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Nathan C.

Funk

Building on what’s

already there

Valuing the local in international peacebuilding

Twenty years have passed since the release of Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s

influential “An agenda for peace.” The publication of this document

coincided with a rapid expansion in United Nations-mandated complex

humanitarian interventions, as well as with new efforts to apply postconflict

peacebuilding as an operative framework for restoring peace and wellbeing

to societies fractured by armed conflict. The present anniversary provides

an opportunity not just for retrospective thinking about the impact of past

international peacebuilding efforts, but also for prospective thinking about

how the next 20 years might be more dynamic and sustainably effective.

The advent of peacebuilding as an evolving practice supported by

the United Nations has created new opportunities for coordinating

constructive responses to protracted conflict. Given its aspiration to develop

instrumentalities for addressing root causes of violence and establishing

foundations for stable peace, peacebuilding represents a significant

Nathan C. Funk is associate professor of peace and conflict studies at Conrad Grebel

University College, University of Waterloo.

| International Journal | Spring 2012 | 391 |

| Nathan C. Funk |

development in thinking about problems of human insecurity, and helps

to shape collective intentionality in ways that support lasting solutions.

Nonetheless, deficits and challenges in contemporary peace practices must

be faced squarely if we are to define a new or renewed peacebuilding agenda

for the decades ahead. Increased international capacity to mitigate organized

violence and provide relief to suffering populations has not yet been matched

with a corresponding ability to make peace stick or to avoid the dangers and

pitfalls associated with large-scale external intervention in fragmented and

fragile societies. Activities undertaken in the name of peacebuilding have

often marginalized local actors, proceeded in ways that did not adequately

respond to local expectations and needs, and at times replaced one set of

problems with another. In many cases, efforts to “transplant” peace through

international peacebuilding efforts yield disappointing results—a temporary

reduction in armed violence, but not a robust and deeply rooted process of

reconstruction and social transformation.

In light of these challenges, there is a need to acknowledge local agency

and empowerment as one of the foremost challenges of contemporary

peacebuilding practice. If a special commission were to rewrite “An agenda

for peace” to incorporate lessons from the last 20 years of peacebuilding

experience, its authors would be well advised to “localize peace”—that

is, to partner with local actors to tap indigenous peace resources and

energize context-specific peace processes—as a central goal of 21st century

peacebuilding efforts.

FROM GALTUNG TO BOUTROS-GHALI AND BEYOND

Peacebuilding is a subject and activity that predates the work of the United

Nations’ sixth secretary-general, but that was nonetheless substantially

influenced by his contributions. In its early uses, the term “peacebuilding”

held currency almost exclusively among academic specialists in the

enterprise known as peace research. Though the peace research tradition

is seldom credited for its impact on Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s formulation,

the intellectual fingerprints of peace scholars are readily apparent. An

early usage of the term peacebuilding can be found in the writings of

Johan Galtung, who conceptualized it as one of three approaches to peace,

alongside peacekeeping and peacemaking. Like Boutros-Ghali, Galtung

contrasts peacebuilding with both peacekeeping and peacemaking. He

describes peacekeeping as a “dissociative” path to peace: “the antagonists are

kept away from each other under mutual threats of considerable punishment

| 392 | Spring 2012 | International Journal |

| Building on what’s already there |

if they transgress, particularly if they transgress into each other’s territory.”1

In contrast, Galtung designates peacemaking as “the conflict resolution

approach” and peacebuilding as “the associative approach.”2 Critical of

traditional approaches to keeping the peace through threat and coercion,

Galtung offers a qualified endorsement of the conflict resolution approach—

provided it is not merely an effort to paper over deep inequalities and

divisions—and presents a case for peacebuilding as a process of change

that seeks to redress global as well as intra-national structural violence by

building nonexploitative structures and infrastructures of peace.

This taxonomy of peace practices overlaps in significant ways with

the framework Boutros-Ghali proposed in 1992. Working in response to a

request by the UN security council to develop prescriptions for enhancing

the UN’s capacity in the areas of preventive diplomacy, peacemaking, and

peacekeeping, Boutros-Ghali consulted widely and ultimately saw fit to add

“peacebuilding” to the list of options presented in his agenda. In contrast

to preventive diplomacy, which sought “to prevent disputes from arising

between parties, to prevent existing disputes from escalating into conflicts

and to limit the spread of the latter when they occur,” peacebuilding would

endeavour to address underlying structural conditions and prevent the

recurrence of armed strife after a settlement had been reached. Boutros-

Ghali therefore defined postconflict peacebuilding as “action to identify and

support structures which will tend to strengthen and solidify peace in order

to avoid a relapse into conflict.”3

A key strength of Boutros-Ghali’s conception of peacebuilding was that,

like Galtung’s formulation, it facilitated thinking about peace as more than

just an absence of war. By its very nature, the term invited Boutros-Ghali’s

contemporaries to expand their focus from the traditional instrumentalities

of international deterrence and diplomacy, and to consider foundational

conditions and structures necessary for advancing human security. Though

Boutros-Ghali stopped short of endorsing Galtung’s notion of “positive

peace” and maintained that the “concept of peace is easy to grasp,”4 his

contributions were welcome among peace scholars, conflict resolution

1 Johan Galtung, Peace, War and Defence: Essays in Peace Research, Volume II

(Copenhagen: Christian Ejlers, 1976), 282, emphasis in original.

2 Ibid., 290 and 297.

3 Boutros Boutros-Ghali, “An agenda for peace: Preventive diplomacy and other

matters,” United Nations, New York, 1992.

4 Ibid.

| International Journal | Spring 2012 | 393 |

| Nathan C. Funk |

specialists, and practitioners. Such constituencies affirmed the manner in

which “An agenda for peace” opened the door to thinking about peace not

just as an absence of fighting—a ceasefire—but also as a presence—as a social,

economic, and political order that enables human flourishing, establishes

mutual confidence, secures human rights, and dispenses with sources of

festering resentment and dissatisfaction. Such a peace is predicated not just

on deterrence and security as traditionally defined, but also on factors such as

development, social justice, environmental sustainability, and participation.

From this point forward, peacebuilding quickly became a holistic,

aggregator concept embraced by those who sought to expand the toolbox

of international diplomacy in the interest of reconstruction, reconciliation,

and long-term conflict prevention. Within the language of the UN system,

peacebuilding underscored not only the need to supplement more traditional

approaches to international peacemaking with more vigorous social and

economic, as well as institutional, measures, but also the importance of

pursuing broad-based, multiple-actor strategies for establishing conditions

for peace through the engagement of states, intergovernmental bodies such

as the UN, civil society organizations, and grassroots communities.

Because the notion of peacebuilding affirms the contributions of

nonstate actors working from the bottom up and endeavouring to build

solidarity across conflict lines, the term has been enthusiastically embraced

by a wide range of civil society actors, many of whom have found in the

term a framework that grants greater legitimacy and profile to long-standing

commitments and activities. Service organizations, field workers, and scholar-

practitioners have played a particularly prominent role in the development

of peacebuilding as a field of practice through which individuals who are

neither diplomats nor soldiers can play a significant role in peace processes.

Precisely because this holistic concept has been resonant with many

different actors addressing a wide range of issues, it has also been developed

in different and sometimes divergent ways. Some nonstate actors in the

NGO, social movement, and academic sectors have appropriated the

concept and aligned it with an agenda that favours conflict transformation

over expediency-based conflict resolution, and calls for greater attention

to demands for social justice and reconciliation—the former of which was

particularly central to Galtung’s original peacebuilding priorities. States

and intergovernmental organizations, while not necessarily dismissing

this agenda of social peacebuilding—indeed they often fund it, albeit in

accordance with funding procedures that are not always conducive to long-

term or grassroots projects—have followed a different trajectory of thought

| 394 | Spring 2012 | International Journal |

| Building on what’s already there |

and action, giving increased attention to institutional reforms and state

building.

Numerous questions, therefore, arise: To what extent are the world’s

peacebuilders on the same page, readily meeting challenges of coordination,

common purpose, and collective intentionality? Has peacebuilding become

all things to all people, or does it in fact provide an integrative framework

for complementary and mutually reinforcing actions? Most importantly, is

peacebuilding genuinely advancing the agenda for which it was conceived:

enabling populations afflicted by destructive conflict to overcome bitter

legacies of violence and inequality by establishing positive and mutually

beneficial relationships?

THE CHALLENGE OF HIGH-QUALITY, SUSTAINABLE PEACE

While ambitious and multifaceted peace operations have helped stabilize

deeply fractured societies and reduce direct violence, 20 years of peacebuilding

experience since “An agenda for peace” suggests that much remains to be

learned about addressing root causes of conflict and placing societies on

the path to sustainable peace. Critics of contemporary stabilization and

reconstruction missions have observed that the top-down nature of major

international missions mirrors imbalances within the larger world order, and

frequently results in a low-quality or stalled peace5 that suffers from deficits

in the areas of local empowerment, local ownership, and legitimacy.6 The

introduction of a large foreign presence to a conflict zone tends to engender

a number of conditions that are not necessarily conducive to long-term

peace: failure to tap or cultivate local talent, the development of an economy

that caters to the needs of foreign specialists, friction between internationals

and locals, popular ambivalence about the trajectory of political change, and

a debilitating sense of dependence on powerful outsiders. The brokering

of accords by external actors and the promotion of standard templates for

institutional reform may do little to activate local capacities while making

only modest contributions to relief of the deep psychological, social, and

economic impacts of violent conflict. Too easily, peace can become a series

of events that happen to the general population rather than a participatory

5 Roger Mac Ginty, No War, No Peace: The Rejuvenation of Stalled Peace Processes and

Peace Accords (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

6 Timothy Donais, “Empowerment or imposition? Dilemmas of local ownership in

postconflict peacebuilding processes,” Peace and Change 34, no. 1 (January 2009):

3-26.

| International Journal | Spring 2012 | 395 |

| Nathan C. Funk |

initiative that enables members of a divided society to tap local resources,

rediscover their own vernacular language for peacebuilding, and become

active agents in the construction of a new reality.

Despite credible claims that international capacity for complex

humanitarian missions has increased in recent decades,7 there are also

compelling reasons to subject the current formulas for liberal peacebuilding

to critical scrutiny. The difficulties faced by international missions in

contexts as diverse as Bosnia, Cambodia, and Somalia raise questions about

the limits of outside-in or top-down approaches to peace consolidation

and reconstruction. Noting that efforts to export peace from one context to

another can make things worse or merely replace one problem with another,

Mac Ginty and Donais have called for critical reexamination of prescriptions

that seek to introduce similar technical, institutional, political, and economic

solutions in every context, without tapping local social capital and cultural

imagination or responding to authentically local priorities.8 These authors

suggest that current peacebuilding orthodoxies prevent more flexible

responses to local conditions and perpetuate the historical dialogue deficit

between north and south, west and nonwest. They liken the liberal peace

to an inflexible regimen of reforms and institutional fixes that are exported

to areas of conflict and implanted without local roots, in ways that reflect a

serious power imbalance between outsiders and insiders, accompanied by

paternalism and dependency. Only in the face of setbacks have sponsors of

international interventions and peace support operations begun to consider

more focused engagement with existing cultural resources, including

indigenous approaches to peacemaking, that were hitherto ignored or

regarded as obstacles.9

To meet the peacebuilding needs of the 21st century and create a more

sound and equitable basis for engaging global governance challenges,

more genuinely empowering forms of grassroots mobilization and local-

international partnership are needed. Though humanitarian missions

endorsed by the United Nations and backed by leading states are likely

to remain necessary, practitioners and scholars of peacebuilding must be

7 Human Security Centre, Human Security Report 2005: War and Peace in the 21st

Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

8 Mac Ginty, No War, No Peace; Donais, “Empowerment or imposition?”

9 Roger Mac Ginty, “Traditional and indigenous approaches to peacemaking,” in John

Darby and Roger Mac Ginty, eds., Contemporary Peacemaking, 2nd edition (New York:

Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 120-30.

| 396 | Spring 2012 | International Journal |

| Building on what’s already there |

careful not to resign themselves to a trouble-shooter role within a largely

western, liberal peace framework that narrows discussion of international

conflict issues.10 A strong argument can be made for broadening and

deepening international dialogue about the nature and sources of peace,

and for underscoring the value of context-sensitive peacebuilding efforts

that seek to activate local resources and energize indigenous peacemaking.

While “An agenda for peace” makes a strong argument for the

involvement of the United Nations system and regional organizations in

postconflict peacebuilding, and indeed for the relevance of international

norms concerning democracy and human rights, the challenge of enabling

local populations to create and sustain their own peace remains a pressing

one. As global conversations about peace, governance, and human security

move forward, there is a vital need to reassert the need for balanced

partnership between external and internal actors, as well as the value of

peacebuilding solutions that reflect local needs, values, capacities, and

aspirations. In a world of diverse, noninterchangeable cultural contexts,

there can be no singular, formulaic approach to sustainable international

peacebuilding. Where homogenizing, generic approaches are at best

indifferent to local culture and are premised on the need for a clean break

with the conflict-afflicted past, newer approaches must adopt a humbler

attitude that regards conflict resolution as a cultural activity and seeks forms

of partnership. This means rethinking the role of cultural and historical

context in shaping peacebuilding practice, balancing the need for innovation

with the necessity of historical continuity, and emphasizing the renewable

and potentially dynamic nature of local cultural resources.

VALUING THE LOCAL

To truly privilege the local in international peacebuilding—and not merely

appropriate its symbols or forms for predetermined purposes—new

thinking will be required. The challenges are both intellectual and practical,

and will require innovative research and theoretical synthesis as well as

reflection on the policy frameworks of governments, intergovernmental

organizations, and NGOs. Fortunately the idea of giving more weight to the

local has precedents in peace research and development studies. It is even

possible to speak of a number of emergent themes in the peacebuilding field

10 Oliver P. Richmond, Peace in International Relations (New York: Routledge, 2008);

Oliver P. Richmond and Jason Franks, Liberal Peace Transitions: Between Statebuilding

and Peacebuilding (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009).

| International Journal | Spring 2012 | 397 |

| Nathan C. Funk |

that can contribute to a new agenda for localizing peace, in which peace-

promoting activities are conducted as much as possible with local materials

and resources, and in a manner that activates latent cultural energies, creates

a genuine sense of ownership and empowerment, and heightens prospects

for sustainability. These emergent themes include: understanding peace as

a locally constructed reality, viewing culture as a resource rather than as a

constraint or afterthought, and recognizing that outsiders are most likely to

make positive contributions when they act as facilitators or midwives rather

than headmasters.

Peace as a locally constructed reality

Since the publication of Lederach’s Preparing for Peace, scholars and

practitioners of international peacebuilding have demonstrated increasing

appreciation for the premise that “understanding conflict and developing

appropriate models of handling it will necessarily be rooted in, and must

respect and draw from, the cultural knowledge of a people.”11 While this

wisdom has by no means been integrated in all peace and reconstruction

practices, analysts of grassroots social peacebuilding have increasingly

recognized that peace has a cultural dimension. While ideas about peace

and conflict need not be locally rooted and completely indigenous to be of

use to individuals and groups in any given context, it remains true that every

cultural community has its own vernacular language for conflict and conflict

resolution, along with its own set of commonsense values and standards

that give the concept of peace substance and legitimacy. Exogenous concepts

must always be related to indigenous understandings and aspirations if

peacebuilding is to become something more than a foreign enterprise

implemented from the top down with limited popular participation and

buy-in. Local cultural beliefs and values do not automatically determine

the operative meaning of peace in political discourse, but they do provide

a litmus test through which local populations evaluate the authenticity and

worthiness of a peace process.

A broad, intercultural approach to peacebuilding seeks to engage rather

than bypass or ignore local meanings of peace. Far from being a distraction

from applied work or an invitation to cultural stasis, exploring traditional

peace vocabulary and its current significance for members of a society

can provide a vital way of eliciting shared visions and value priorities, and

11 John Paul Lederach, Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation across Cultures

(Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995), 10.

| 398 | Spring 2012 | International Journal |

| Building on what’s already there |

relating them to realities of conflict in a manner that is conducive to action.

Engaging local peace-related concepts can be part of a larger process that

involves tapping tacit knowledge and establishing more genuinely dialogical

local-international relationships. Much can be learned, for example, from

a discussion of values inherent in the South African principle of ubuntu,12

from an examination of the symbolic and practical requirements of an

Arab-Islamic sulh ritual of reconciliation,13 or from an account of how the

Somali code of conduct known as xeer helped to avert unending conflict in

Somaliland.14

Sound peacebuilding practice begins with recognition that there are

limits to the extent to which any external cultural group or political entity

can bring peace to another community or polity. While there are numerous

ways in which external actors can and should provide needed support to

societies emerging from violent conflict, stable and lasting peace cannot be

enforced on or built for others. Whatever role external coalitions may play in

mitigating destructive conflict, sharing expertise, or reforming international

policies that place strain on fragile social ecologies, peace must ultimately

be constructed locally on a foundation that is recognized as legitimate.

Ideally, peace ought to be built in accordance with a locally negotiated plan

using as many local materials and skills as possible, so that the population

in question acquires a sense of ownership, satisfaction, and capacity for

continued upkeep. In other words, international peacebuilders need to build

on what is already there.

In light of these considerations, agents of peacebuilding must guard

against the unwitting cultural imperialism that inheres not only in “have

technique will travel” approaches to conflict resolution practice but also

in efforts to prescribe and export the same institutional solutions to all

societies.15 Genuinely respectful and productive partnerships are likely to be

informed by use of cultural empathy as a tool of analysis, and by efforts to

use discussion of cultural particularities as a bridge to strategizing about

12 Desmond Tutu, No Future without Forgiveness (New York: Doubleday, 1999).

13 George E. Irani and Nathan C. Funk, “Rituals of reconciliation: Arab-Islamic

perspectives,” Arab Studies Quarterly 20, no. 4 (fall 1998): 53-73.

14 Haroon Yusuf and Robin Le Mare, “Clan elders as conflict mediators: Somaliland,”

in Paul van Tongeren, et al., eds., People Building Peace II: Successful Stories of Civil

Society (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2005), 459-65.

15 Mac Ginty, No War, No Peace; Nathan C. Funk and Abdul Aziz Said, “Localizing

peace: An agenda for sustainable peacebuilding,” Peace and Conflict Studies 17, no. 1

(spring 2010): 101-43.

| International Journal | Spring 2012 | 399 |

| Nathan C. Funk |

appropriate ways and means. Such partnerships recognize that local actors

must own the peace that is to be built, and are only likely to be committed to

the result if it reflects their own priorities, meanings, and aspirations.

Culture as a resource

Sophisticated analysts of culture recognize that, while it is the matrix within

which social practices take form, it is not a static, monolithic, or deterministic

structure.16 When people become self-aware with respect to their cultural

inheritance, it can be understood and engaged as a resource rather than

construed as an obstacle or as an unchanging whole to be defended at any

cost.17 Significant links to the past can be preserved, even as some traditions

are consciously maintained and others are subjected to critique or adaptation.

In many respects, peacebuilding is a process of cultural introspection

and reconstruction—a process of generating social dialogue that encourages

critical reflection on existing realities, the reevaluation of present value

priorities, and the initiation of new, shared projects that reduce the gap

between real and ideal. An essential part of peacebuilding projects, therefore,

is balancing cultural innovation with cultural continuity. There is a need

for change, but it must proceed on an authentic and locally valid basis or

rationale. It must discover new meaning, relevance, and applicability in

known values and beliefs.18

Using culture as a resource can begin with the recognition that cultural

and religious heritages are internally contested, and provide complex sets of

practices, values, and precedents that can be applied in divergent (including

peaceful as well as combative) ways.19 For example, any cultural community

with deep historical roots is likely to discover multiple precedents for relations

with outsiders or for processes of collective decision-making. Viewing

culture as a resource provides the basis for a dynamic view, freeing groups

of practitioners to seek the best within their heritage and thereby avoid the

16 Kevin Avruch, Culture and Conflict Resolution (Washington, DC: United States

Institute of Peace Press, 1998).

17 Lederach, Preparing for Peace; Donais, “Empowerment or imposition?”

18 Howard Richards and Joanna Swanger, “Culture change: A practical method with

a theoretical basis,” in Joseph de Rivera, ed., Handbook on Building Cultures of Peace

(New York: Springer, 2009), 57-70.

19 R. Scott Appleby, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation

(Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2000).

| 400 | Spring 2012 | International Journal |

| Building on what’s already there |

alienation that ensues when cultural traditions are either suppressed in the

pursuit of forced modernization or not allowed to grow and change.

The potential for genuinely sustainable, effective, and empowering

peacebuilding initiatives increases dramatically when culture is understood

as a resource and source of inspiration but not as a rigid mould or

invariant template. The sustainability of contextually grounded peace

efforts is a function of the fact that indigenous cultural resources (in

contrast to resources brought by intergovernmental and international

nongovernmental organizations, or by development agencies from foreign

nations) are intrinsically renewable through the application of local skills

and knowledge. They have greater prospects for effectiveness because local

materials are more likely to be accepted and to have a multiplier effect than

imports that are regarded as foreign. They are empowering because they

enable local change agents to advance peace using tools and symbols that are

familiar and culturally legitimate.

The pursuit of local solutions to the problems of peacebuilding need not

exclude external involvement, resources, and support, nor does it presume

that local traditions are not in need of refinement. Indeed, if local resources

were fully developed and operational, the local peace would already be made.

Localizing peace should not be confused with turning back the clock or fully

restoring traditional institutions that no longer command a broad social

consensus. Insofar as large-scale violent conflict has a destabilizing effect on

social institutions, damaging the networks that were once responsible for

conflict management, cultural resources may have to undergo considerable

adaptation or revitalization before they can become operative in a changing

social milieu.20 Moreover, some local traditions may exclude or marginalize

voices—for example, those of women, children, or members of outcaste

groups—that are vital to the consolidation of a high-quality, sustainable

peace.21 In such cases it is crucial for outside parties to become familiar with

indigenous currents of dissent and proposals for change and renewal.

Outsider as facilitator

As Donais has observed, “outsiders too often take the legitimacy of

themselves and their programs as self-evident without seriously considering

20 Ho-won Jeong, Peacebuilding in Postconflict Societies: Strategy and Process (Boulder:

Lynne Rienner, 2005), 182-84.

21 Sanam Naraghi Anderlini, Women Building Peace: What They Do and Why it Matters

(Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2007).

| International Journal | Spring 2012 | 401 |

| Nathan C. Funk |

the degree to which, for local actors, legitimacy must be rooted in their own

history and political culture.”22 While it is true that outsiders often possess

knowledge and experience that has much potential value, it is also true that

locals possess an expertise relative to their own situation that no outsider can

fully encompass.

Given these realities, there is wisdom in Lederach’s counsel to balance

prescriptive and elicitive modes of training and to direct consultations

organized by outsiders towards the refinement of locally resonant models.23

The point is not to abolish the role of the external consultant, but rather to

develop a humbler mode of operation in which the outsider functions as a

facilitator or midwife whose overriding goal is to help local actors discover

their own resources and context-specific solutions. In this respect, the

international peacebuilding practitioner can adopt elements of a maieutic or

Socratic approach to pedagogy, in which dialogue is at the core of a mutual

learning process and there is no assumption that the person speaking is

necessarily wiser than those who are being engaged.

When outsiders share their own models for peace and peacebuilding, it is

important to clarify also the historical experiences and cultural assumptions

from which these models emerge. The experiences of reflective practitioners

indicate that there is no set of conflict resolution practices that works equally

well in every setting; while general principles may translate, methods and

techniques are often culture-specific.24 Moreover, people are more likely to

become empowered when drawing upon their own cultural vocabulary to

discover indigenous resources.25 In this respect, the peacebuilding field can

benefit from the insights of the appropriate technology movement, which

seeks to make development practice more innovatively responsive to the

immediately experienced needs, available resources, and existing knowledge

of people living in modest circumstances, and less focused on the transfer

of specialized technologies from industrialized countries.26 Similarly, the

22 Donais, “Empowerment or imposition?” 20.

23 Lederach, Preparing for Peace.

24 Mohammed Abu-Nimer, “Conflict resolution approaches: Western and Middle

Eastern lessons and possibilities,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 55, no.

1 (1996): 35-53; Funk and Said, “Localizing peace.”

25 Jannie Malan, “Traditional and local conflict resolution,” in People Building Peace

II, 449-58.

26 E. F. Schumacher, “Buddhist economics,” in Guy Wint, ed., Asia: A Handbook

(London: Anthony Blond, 1966); E. F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful: Economics as if

People Mattered (New York: Harper & Row, 1973).

| 402 | Spring 2012 | International Journal |

| Building on what’s already there |

most appropriate peacebuilding methods in a given cultural context may be

updates of traditional or indigenous methods rather than imported western

or North American models. Because these applications build upon that

which is familiar, they stand a greater chance of being diffused throughout

a social setting.

ACTIVATING LOCAL RESOURCES

Both international peacebuilders and local populations often underestimate

or neglect indigenous resources and fail to appreciate ways in which capacity

to deal with conflict constructively might be enhanced through a process of

cultural introspection, dialogue, and renewal. While the principle of localism

should not be applied with excessive rigidity—peacebuilders in all parts

of the world can benefit from cross-cultural learning—there is a need for

further thinking about the nature of readily available local materials, and for

reflection on the many different types of resources that can be constructively

used to enhance the vitality, sustainability, legitimacy, and resilience of

peacebuilding efforts.

Though religious and cultural identities often serve as markers of

difference and are at least partially co-opted by the systems of confrontation

that develop amid protracted conflict, they are also sources of values, beliefs,

and narratives that can be of profound importance for peacemaking. In

many parts of the world, the vernacular language for speaking about peace

and conflict is infused with religious content, and conversations about

aspirations toward peace and reconciliation almost inevitably lead toward

discussion of religious values, texts, and traditions. Indigenous peacemaking

events regularly feature references to religious scriptures and to the words

of exemplary spiritual figures, and may also—like the South African truth

and reconciliation commission—evoke a sense of religious symbolism and

ritual.27

The broader sweep of historical experience should also be recognized

as a local peace resource. Mining this experience can bring to the surface

not only memories of past traumas, but also stories of peacemaking and

knowledge of indigenous processes of community dispute resolution.28

27 Megan Shore, Religion and Conflict Resolution: Christianity and South Africa’s Truth

and Reconciliation Commission (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009).

28 David Augsburger, Conflict Mediation across Cultures (Louisville, KY: Westminster/

John Knox Press, 1992); Joseph Wasonga, “Rediscovering mato oput: The Acholi

justice system and the conflict in northern Uganda,” Africa Peace and Conflict Journal

2, no. 1 (2009): 27-38.

| International Journal | Spring 2012 | 403 |

| Nathan C. Funk |

People’s familiarity with traditional peacemaking narratives and methods

may provide a basis for rich dialogue with respect to the values, skills,

and processes that are required to make peace, articulated in the cultural

vernacular rather than in the vocabulary of social theory or diplomacy. In

some settings, such dialogue may direct attention to past peacemaking

methods that have been marginalized during a current conflict, but which

nonetheless constitute a valuable frame of reference for renewed efforts.

As Lederach notes, the language, metaphors, and proverbs people use

to describe their reality can be an especially rich source of insight into

implicit knowledge, and can provide a basis for surfacing local models of

peacemaking.29

Local social capital and commonsense knowledge should also be

regarded as resources. When taking inventory of local assets, a wide

variety of existing institutions, social movements, skilled individuals, and

stakeholders merit recognition, beyond the limited circle of organizations

that are most well-connected to international NGOs and foreign missions.

On-the-ground experience with the dynamics of a unique political situation

is also an identifiable resource that newcomers do not possess, as is the

detailed, fine-grained knowledge that people have of their own reality, needs,

and immediately available means.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The potential value of localized peacemaking approaches is already receiving

recognition in the field of transitional justice, and is generating new

conversations about possibilities for complementarity between western and

indigenous practices. As Mac Ginty has noted, traditional and indigenous

approaches to peace have the potential to address deficiencies in “orthodox

Western approaches” by engaging the “affective dimension of peacemaking”

in a culturally appropriate manner, and by balancing the top-down, elite-

focused aspect of conventional intervention programs with a more genuinely

participatory and bottom-up dynamic.30 In settings as diverse as Rwanda,

East Timor, and Afghanistan, many international missions have recognized

limits to the reach and practicality of conventional methods, and have sought

to learn about, create space for, and encourage adapted applications of

traditional dispute resolution, mediation, and consensus-building practices.

29 Lederach, Preparing for Peace.

30 Mac Ginty, “Traditional and indigenous approaches to peacemaking,” 128-29.

| 404 | Spring 2012 | International Journal |

| Building on what’s already there |

While practices such as Rwanda’s community-level gacaca courts,31 East

Timor’s nahe biti community reconciliation process,32 and Afghanistan’s

loya jirga (grand council) still require critical evaluation, they are receiving

recognition by western diplomats and policy thinkers and new conversations

are emerging about the most appropriate way to tap the strengths of the

indigenous without depriving it of authenticity and legitimacy through co-

optation.33 The subject appears to defy simple, formulaic solutions, yet given

the possibility that indigenous processes might easily be misappropriated by

external agents and agendas, the need for guidelines and criteria is pressing.

The following suggestions are necessarily preliminary and incomplete,

and are offered in the hope that they will inspire further discussion about

how best to advance principled engagement with the local in international

peacebuilding.

One of the more important prerequisites for locally empowering practice

is a compelling and dynamic vision that can be used to inform day-to-day

peacebuilding choices. Concepts such as sustainability, capacity building,

appropriate technology, and local ownership are not alien to peacebuilding

and development practice. But pressure to show quick, measurable results

often subverts efforts to pursue these goals through long-term relationship

building and the pursuit of custom-built, context-specific solutions to local

problems. Making the case for a local-friendly approach to international

peace and development work will no doubt require considerable effort on

the part of researchers, as well as political courage and communicative

competence on the part of administrators. The fact that local resources

are more renewable than international resources bears repeating, as does

the commonsense insight that lasting cultural change is the work of viable

grassroots movements and not a matter of short-term service delivery.

Localizing peace also requires considerable forethought about how

international peacebuilding personnel are trained for service. Working

effectively requires not just familiarity with models of cultural competence

or incentives for learning local language and history, but also forms of

training that use suitable case study materials. Organizations will also need

to develop guidelines for work in the field that enumerate principles for

31 Charles Villa-Vicencio, Paul Nantulya, and Tyrone Savage, Building Nations:

Transitional Justice in the African Great Lakes Region (Cape Town: Institute for Justice

and Reconciliation, 2005).

32 Mac Ginty, “Traditional and indigenous approaches to peacemaking,” 128-29.

33 Ibid.

| International Journal | Spring 2012 | 405 |

| Nathan C. Funk |

localizing peace—e.g., exploring local cultural and religious traditions with

interest and respect; applying cultural empathy as a tool of analysis; using

culture as a bridge, by asking about how things would “normally” or “ideally”

be done; linking localized needs assessments to elicitive exercises intended

to access implicit cultural knowledge and promote empowerment; initiating

a “cultural inventory” of resources for peacebuilding; fostering discussion

about how to strengthen a local culture of peace by adapting and updating

past practices; and so forth.

Concern to tap indigenous cultural resources should not distract

international peacebuilders from opportunities to share varieties of expertise

that are genuinely desired and needed, in a spirit of cultural exchange.34

Training in conflict resolution can be used as an opportunity for two-way

learning, as can discussion of matters such as approaches to strategic

planning, communications, and public education. Opportunities can also be

sought to build bridges between local organizations and actors operating in

different world regions. In the 1990s, for example, members of an emerging

Lebanese conflict resolution network (assisted at the time by the US-based

NGO, Search for Common Ground) found great meaning in an opportunity

to explore conflict resolution with a South African trainer.

Not all local practices, of course, are an aid to peace. Efforts to support

the localization of peace must acknowledge that some traditional practices

may no longer be experienced as positive and relevant. The local is not always

better than the nonlocal, and workable solutions are often a result of cross-

fertilization among cultures. In addition, the intrinsically interpretive nature

of culture can present many opportunities for creativity and dynamism.

Processes of reform in any culture almost always involve sifting through

traditions for foundational values that can be understood and applied in new

ways, providing a bridge between past and future.

CONCLUSION

International and cross-cultural cooperation remain vital for tackling

border-spanning problems and structural inequalities. As Boutros-Ghali

recognized, peace requires discussions about human rights, infrastructure

enhancement, economic revitalization, and administrative reform—not

to mention structural prevention and transnational social justice, which

were central concerns in Galtung’s early formulation of peacebuilding.

Nonetheless, peacebuilding has to build on what is already exists, and the

34 Donais, “Empowerment or imposition?”

| 406 | Spring 2012 | International Journal |

| Building on what’s already there |

advancement of global peace depends in no small part on the progress

of diverse local peace processes. Ultimately, peace must be defined and

constructed locally, and peacebuilding efforts become energetic and

sustainable only to the extent that they tap and refine indigenous resources,

empower local constituencies, and achieve legitimacy within particular

cultural and indeed religious contexts.

Some of the more remarkable peacebuilding stories of the last two

decades are not to be found in places like Cambodia, East Timor, or the

Balkans, where there were major, complex international missions, but

rather in places in which an on-the-ground international presence was not

determinative, such as Somaliland, Mozambique, and South Africa. Such

examples give credit to the idea that a strong, internally driven process can

affect changes that international parties cannot, and invite reflection on how

humbler, but still proactive, approaches to peacebuilding might support and

advance—but not predetermine or direct—sustainable initiatives.

Attuning agendas for peacebuilding to the limits of standardized

western approaches can be accomplished without negating the necessity

of global engagement, responsibility, and collaboration. International and

cross-cultural cooperation remain vital for addressing the border-spanning

problems of the 21st century. However, the process of seeking greater

consensus on the character of global peace cannot proceed independently

from efforts to support the grounded construction of diverse “local peaces”—

contextually viable peace capacities that reflect the cultural distinctiveness of

lived human experience, and which will ultimately make up the foundation

stones for a more genuinely inclusive and multicultural global peace project.

Insofar as successful peacebuilding is rooted in shared meaning and purpose

and not in techniques and institutions alone, peacebuilding efforts must

respond directly to locally felt needs for dignity, authenticity, and wellbeing.

In a diverse world, there can be no singular, formulaic approach to

international peacebuilding. Where homogenizing, generic approaches

are at best indifferent to local culture and are premised on the need for a

clean break with the conflict-afflicted past, newer approaches can recognize

conflict resolution as a cultural activity and seek forms of partnership that

help to midwife local efforts. This means rethinking the role of context

in shaping peacemaking practice, balancing the need for innovation with

the necessity of historical continuity, and emphasizing the renewable and

potentially dynamic nature of local cultural resources.

By appreciating these realities, international actors can discover more

effective means of partnering with local organizations and movements, while

| International Journal | Spring 2012 | 407 |

| Nathan C. Funk |

also deriving new insights into the unity and diversity of peacebuilding. For

peacebuilders from contexts such as North America and Europe, stronger

resolve to learn from and to be enriched by what the local has to offer could

bring many benefits. In addition to cultural self-awareness, contemporary

peacebuilders would also be well-advised to cultivate an attitude of

complementarity, within which there is appreciation for ways in which the

field of peacebuilding can be enhanced by nonwestern contributions.

By more fully appreciating and engaging local resources for peace,

practitioners of international conflict resolution stand not only to enhance

the vitality of peace processes, but also to benefit from discoveries of

resonance among diverse peacemaking traditions. Rather than encouraging

isolationism in the pursuit of peace, the aspiration to localize peace constitutes

an effort to make peace real at the level of lived human experience as well as

at broader structural and global levels. It invites theorists and practitioners

alike to expand the cultural horizons of their field, with the understanding

that bringing more voices to the table is itself a peace process—a process

of acknowledging and respecting the many parts, without which a greater

whole cannot be envisioned or realized.

| 408 | Spring 2012 | International Journal |

Symposium

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Peacebuilding and Reconciliation: Contemporary Themes and ChallengesD'EverandPeacebuilding and Reconciliation: Contemporary Themes and ChallengesPas encore d'évaluation

- Intro To PeacebuildingDocument13 pagesIntro To PeacebuildingesshorPas encore d'évaluation

- Powering to Peace: Integrated Civil Resistance and Peacebuilding StrategiesD'EverandPowering to Peace: Integrated Civil Resistance and Peacebuilding StrategiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 14 Approaches To PeacebuildingDocument10 pagesUnit 14 Approaches To PeacebuildingParag ShrivastavaPas encore d'évaluation

- ConceptPaper AccordincentivesDocument14 pagesConceptPaper AccordincentivesAslanie MacadatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 3Document11 pagesUnit 3Raj KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 13 Peacebuilding - Meaning and SignificanceDocument45 pagesUnit 13 Peacebuilding - Meaning and SignificanceRamanPas encore d'évaluation

- SEC Unit 1 (C)Document9 pagesSEC Unit 1 (C)Vidisha KaushikPas encore d'évaluation

- PeacebuildingDocument3 pagesPeacebuildingFifen Yahya MefiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Effective Community Participation in The Process of Peace Building and CoDocument15 pagesEffective Community Participation in The Process of Peace Building and Cosaudiya kassim aliyuPas encore d'évaluation

- Group Three Social Research Assignment 1.ibrahim Abdi 2.mohamed Yusuf 3.abdualahi Mohamud 4.nageeyeDocument9 pagesGroup Three Social Research Assignment 1.ibrahim Abdi 2.mohamed Yusuf 3.abdualahi Mohamud 4.nageeyeibrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- AntiImperialism AffDocument2 pagesAntiImperialism AffutnifdebatePas encore d'évaluation

- CH 6Document13 pagesCH 6Nasser Thiab AL-EshaqPas encore d'évaluation

- Women, Gender, PeacebuilidngBRADFORDDocument40 pagesWomen, Gender, PeacebuilidngBRADFORDMaribel HernándezPas encore d'évaluation

- Conflict Prevention and Preventive Diplomacy: Opportunities and ObstaclesDocument9 pagesConflict Prevention and Preventive Diplomacy: Opportunities and ObstaclesStability: International Journal of Security & DevelopmentPas encore d'évaluation

- FromwarstocpesDocument14 pagesFromwarstocpesFREDDY ARKAR MOE MYINTPas encore d'évaluation

- 2007 Peacebuilding GGDocument24 pages2007 Peacebuilding GGXimena SierraPas encore d'évaluation

- Peace and ConflictDocument11 pagesPeace and Conflictabhishek rupaniPas encore d'évaluation

- MALUYA, Gwyneth Assignment#2Document3 pagesMALUYA, Gwyneth Assignment#2Maluya GwynethPas encore d'évaluation

- RBC A Strategy For PeaceDocument10 pagesRBC A Strategy For PeaceQhip NayraPas encore d'évaluation

- Peace BuildingDocument12 pagesPeace BuildingOMGITSGADINGPas encore d'évaluation

- Louis Assignment 2Document15 pagesLouis Assignment 2joshuanyengierefaka54Pas encore d'évaluation

- GST222 Post Conflict PeacebuildingDocument18 pagesGST222 Post Conflict PeacebuildingPrincess Oria-ArebunPas encore d'évaluation

- Post Conflict StatebuildingDocument4 pagesPost Conflict StatebuildingSafiya TadefiPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation For Contemporary DiplomacyDocument7 pagesPresentation For Contemporary DiplomacyAzuan EffendyPas encore d'évaluation

- Completed Book PeacebuildingDocument53 pagesCompleted Book PeacebuildingNuradin Sharif HashimPas encore d'évaluation

- Peace Ed Grade 6Document16 pagesPeace Ed Grade 6Florence Butac ViernesPas encore d'évaluation

- Peacebuilding What Is in A NameDocument25 pagesPeacebuilding What Is in A NameMyrian100% (1)

- For DecadesDocument1 pageFor DecadesChitrakshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Peacemaking, Peacekeeping and Peacebuilding: Dr. Aslam KhanDocument16 pagesPeacemaking, Peacekeeping and Peacebuilding: Dr. Aslam KhanHassan NazirPas encore d'évaluation

- Conflicts vs. Disputes: José Antonio de AbreuDocument19 pagesConflicts vs. Disputes: José Antonio de AbreuHillary ZambranoPas encore d'évaluation

- Peace EducationDocument12 pagesPeace EducationWinnie PascualPas encore d'évaluation

- EhenDocument13 pagesEhenCris PascasioPas encore d'évaluation

- Community Based Strategies For Peace and SecurityDocument4 pagesCommunity Based Strategies For Peace and Securityapi-511007472Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dilemmas in Planning Crisis Prevention: Ngos in The Chittagong Hill Tracts of BangladeshDocument16 pagesDilemmas in Planning Crisis Prevention: Ngos in The Chittagong Hill Tracts of BangladeshbonedPas encore d'évaluation

- Texts - Building Peace - Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies (Leberach)Document205 pagesTexts - Building Peace - Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies (Leberach)esshor100% (3)

- Guia de Mediação - Possibilitando A Paz em Conflitos ArmadosDocument44 pagesGuia de Mediação - Possibilitando A Paz em Conflitos ArmadosArthur SchreiberPas encore d'évaluation

- HPG Stability ReportDocument29 pagesHPG Stability ReportkirkstefanskiPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Peacebuilding State of The FieldDocument17 pagesStrategic Peacebuilding State of The Fieldjual76100% (3)

- Socio-Economic Crises SecurityDocument19 pagesSocio-Economic Crises SecurityMaria KiranPas encore d'évaluation

- Organization Theory and Complex Peacekeeping Operations: Notes From The MinustahDocument16 pagesOrganization Theory and Complex Peacekeeping Operations: Notes From The MinustahCHRISTINE BONAJOSPas encore d'évaluation

- Conflict Resolution in Modern EraDocument4 pagesConflict Resolution in Modern EraCousins HasanovsPas encore d'évaluation

- Against StabilizationDocument12 pagesAgainst StabilizationStability: International Journal of Security & DevelopmentPas encore d'évaluation

- Stuart Kaufman October 2000 PONARS Policy Memo 164 University of KentuckyDocument5 pagesStuart Kaufman October 2000 PONARS Policy Memo 164 University of KentuckyКаро ПетросянPas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiation in Int LawDocument7 pagesNegotiation in Int LawKbh Bht89Pas encore d'évaluation

- Peace-Building After AfghanistanDocument22 pagesPeace-Building After AfghanistanDimitri PanaretosPas encore d'évaluation

- Short Mediation ReadingDocument4 pagesShort Mediation ReadingMarcela Martínez CastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 2008 FRIDE Human Security and PeacebuidingDocument11 pages2008 FRIDE Human Security and PeacebuidingTey TanaPas encore d'évaluation

- John Paul Lederach Building Peace SustainableDocument205 pagesJohn Paul Lederach Building Peace SustainableBader50% (2)

- Briefing Paper Briefing Paper: State-Building For Peace': Navigating An Arena of ContradictionsDocument4 pagesBriefing Paper Briefing Paper: State-Building For Peace': Navigating An Arena of ContradictionsFrancisco cossaPas encore d'évaluation

- In What Ways Have Feminist Analyses Both Challenged and Developed Academic and Policy Approaches To Peacebuilding?Document11 pagesIn What Ways Have Feminist Analyses Both Challenged and Developed Academic and Policy Approaches To Peacebuilding?Laura BartleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Editors' Foreword: Introducing Stability - International Journal of Security and DevelopmentDocument4 pagesEditors' Foreword: Introducing Stability - International Journal of Security and DevelopmentStability: International Journal of Security & DevelopmentPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Peace Building in ColombiaDocument15 pagesUnderstanding Peace Building in ColombiaJavier VelezPas encore d'évaluation

- Madhurima - PCD A3Document9 pagesMadhurima - PCD A3Madhurima GuhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Conflict PreventionDocument13 pagesConflict PreventionTatiana SimõesPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit Peace Research and Peace Movements: StructureDocument17 pagesUnit Peace Research and Peace Movements: StructureNeha GautamPas encore d'évaluation

- Peace Studies and Conflict ResolutionDocument42 pagesPeace Studies and Conflict ResolutionKolade AwoleyePas encore d'évaluation

- Conflict Management For PeacekeepersDocument18 pagesConflict Management For Peacekeepersgosaye desalegnPas encore d'évaluation

- Peacebuilding: Imperialism's New Disguise?: Annette Seegers Constanze SchellhaasDocument14 pagesPeacebuilding: Imperialism's New Disguise?: Annette Seegers Constanze SchellhaasGertrude RosenPas encore d'évaluation

- 87329-Article Text-216068-1-10-20130415 PDFDocument22 pages87329-Article Text-216068-1-10-20130415 PDFAshique BhuiyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Export Descr UnitDocument220 pagesExport Descr UnitJoshua NgPas encore d'évaluation

- War and State Formation in Ethiopia and EritreaDocument14 pagesWar and State Formation in Ethiopia and EritreaHeeDoeKwonPas encore d'évaluation

- Song of Drums and Shakos Errata Clarifications EtcDocument6 pagesSong of Drums and Shakos Errata Clarifications EtcPete GillPas encore d'évaluation

- Doctrine and Dogma - German and British Infantry Tactics in The First World War PDFDocument14 pagesDoctrine and Dogma - German and British Infantry Tactics in The First World War PDFEugen PinakPas encore d'évaluation

- Two Page Assignment On American Civil WarDocument6 pagesTwo Page Assignment On American Civil WarTanaka MuvezwaPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Wargame 1984-1988 PDFDocument194 pagesGlobal Wargame 1984-1988 PDFJonathan WeygandtPas encore d'évaluation

- 9-8-1966 Operation HawthorneDocument30 pages9-8-1966 Operation HawthorneRobert Vale100% (1)

- Kingdoms of Camelot GuideDocument11 pagesKingdoms of Camelot Guidedannys2sPas encore d'évaluation

- Society For Military HistoryDocument7 pagesSociety For Military HistoryGabriel QuintanilhaPas encore d'évaluation

- In Pictures Massacre of Gazan ChildrenDocument18 pagesIn Pictures Massacre of Gazan ChildrenivanardilaPas encore d'évaluation

- TEMPUS Lord of Battles Forgotten Realms 5eDocument12 pagesTEMPUS Lord of Battles Forgotten Realms 5eChuck TheKniferPas encore d'évaluation

- Laws Governing Insurgency and Belligerency in International LawDocument7 pagesLaws Governing Insurgency and Belligerency in International LawTeenagespiritsPas encore d'évaluation

- Causes of WWI WebquestDocument3 pagesCauses of WWI WebquestNoope FakePas encore d'évaluation

- History Chapter 10Document8 pagesHistory Chapter 10siddesh mankarPas encore d'évaluation

- Divisional Artillery Brigade, Force XXI, Forward Artillery Battalion, M-109 - 06365F000Document4 pagesDivisional Artillery Brigade, Force XXI, Forward Artillery Battalion, M-109 - 06365F000Martin WhitenerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Battle of Binh Ba: A Baffling "Mystery" and SIGINT Failure ? - NO!Document2 pagesThe Battle of Binh Ba: A Baffling "Mystery" and SIGINT Failure ? - NO!Ernest Patrick ChamberlainPas encore d'évaluation

- Approaches To PeaceDocument17 pagesApproaches To PeacePankaj PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Club of Rome New World OrderDocument24 pagesClub of Rome New World Ordernortherndisclosure100% (2)

- Powerpoint PresentationDocument22 pagesPowerpoint Presentationapi-325794919Pas encore d'évaluation

- SelectedPapersofGeneralWilliamDepuy PDFDocument490 pagesSelectedPapersofGeneralWilliamDepuy PDFn0dazePas encore d'évaluation

- Silk Road Headquarters: Silk Roads (1st Century BC-5th Century AD, and 13th-14th Centuries AD)Document6 pagesSilk Road Headquarters: Silk Roads (1st Century BC-5th Century AD, and 13th-14th Centuries AD)Shi GiananPas encore d'évaluation

- Osprey 2018 PDFDocument36 pagesOsprey 2018 PDFThomaz Lipparelli100% (1)

- Relictors SpearheadDocument1 pageRelictors SpearheadCharyouPas encore d'évaluation

- Habermas Hannah Arendt S Communications Concept of PowerDocument10 pagesHabermas Hannah Arendt S Communications Concept of PowerDavid Cruz FerrerPas encore d'évaluation

- Osprey ESS035 WWII (2) Europe 1939-43 PDFDocument96 pagesOsprey ESS035 WWII (2) Europe 1939-43 PDFbigpiers100% (1)

- Israel Palestine Conflict Sample UN-ResolutionDocument2 pagesIsrael Palestine Conflict Sample UN-ResolutionChris ChiangPas encore d'évaluation

- Middle East History Study Guide Answer Key-HayesDocument3 pagesMiddle East History Study Guide Answer Key-Hayesapi-293087127Pas encore d'évaluation

- Redo Essay #1Document6 pagesRedo Essay #1Abraham MunozPas encore d'évaluation

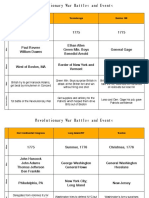

- Revolutionary War Battles Chart Answers 2017Document4 pagesRevolutionary War Battles Chart Answers 2017api-314922612100% (2)

- Russo-Ukrainian War - WikipediaDocument368 pagesRusso-Ukrainian War - WikipediaAssffPas encore d'évaluation

- Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarD'EverandReagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (4)

- Cry from the Deep: The Sinking of the KurskD'EverandCry from the Deep: The Sinking of the KurskÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (6)

- The Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of PowerD'EverandThe Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of PowerÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (14)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyD'EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (7)

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaD'EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (23)

- Palestine Peace Not Apartheid: Peace Not ApartheidD'EverandPalestine Peace Not Apartheid: Peace Not ApartheidÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (197)

- New Cold Wars: China’s rise, Russia’s invasion, and America’s struggle to defend the WestD'EverandNew Cold Wars: China’s rise, Russia’s invasion, and America’s struggle to defend the WestPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Intelligence Collector OperationsD'EverandHuman Intelligence Collector OperationsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyD'EverandThe Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (13)

- How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales from the PentagonD'EverandHow Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales from the PentagonÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (40)

- The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear WarD'EverandThe Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear WarÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (41)

- The Generals Have No Clothes: The Untold Story of Our Endless WarsD'EverandThe Generals Have No Clothes: The Untold Story of Our Endless WarsÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (3)

- How the West Brought War to Ukraine: Understanding How U.S. and NATO Policies Led to Crisis, War, and the Risk of Nuclear CatastropheD'EverandHow the West Brought War to Ukraine: Understanding How U.S. and NATO Policies Led to Crisis, War, and the Risk of Nuclear CatastropheÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (17)

- Never Give an Inch: Fighting for the America I LoveD'EverandNever Give an Inch: Fighting for the America I LoveÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (10)

- The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerD'EverandThe Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (47)

- International Relations: A Very Short IntroductionD'EverandInternational Relations: A Very Short IntroductionÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (6)

- Never Give an Inch: Fighting for the America I LoveD'EverandNever Give an Inch: Fighting for the America I LoveÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (31)

- Is This the End of the Liberal International Order?: The Munk Debate on GeopoliticsD'EverandIs This the End of the Liberal International Order?: The Munk Debate on GeopoliticsPas encore d'évaluation

- Soft Power on Hard Problems: Strategic Influence in Irregular WarfareD'EverandSoft Power on Hard Problems: Strategic Influence in Irregular WarfarePas encore d'évaluation

- War and Peace: FDR's Final Odyssey: D-Day to Yalta, 1943–1945D'EverandWar and Peace: FDR's Final Odyssey: D-Day to Yalta, 1943–1945Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (4)

- Conflict: The Evolution of Warfare from 1945 to UkraineD'EverandConflict: The Evolution of Warfare from 1945 to UkraineÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (2)

- Mossad: The Greatest Missions of the Israeli Secret ServiceD'EverandMossad: The Greatest Missions of the Israeli Secret ServiceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (84)

- Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United StatesD'EverandTreacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United StatesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (8)

- The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital AgeD'EverandThe New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital AgePas encore d'évaluation

- The Coup: 1953, the CIA, and the Roots of Modern U.S.-Iranian RelationsD'EverandThe Coup: 1953, the CIA, and the Roots of Modern U.S.-Iranian RelationsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern WarD'EverandThe Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern WarÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (4)