Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Thinking Ethnographically

Transféré par

Mica ElaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Thinking Ethnographically

Transféré par

Mica ElaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Defining Social Reality

In: Thinking Ethnographically

By: Paul Atkinson

Pub. Date: 2017

Access Date: March 6, 2018

Publishing Company: SAGE Publications Ltd

City: 55 City Road

Print ISBN: 9780857025906

Online ISBN: 9781473982741

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781473982741

Print pages: 20-42

©2017 SAGE Publications Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This PDF has been generated from SAGE Research Methods. Please note that the

pagination of the online version will vary from the pagination of the print book.

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

Defining Social Reality

Introduction

Social realities, social life-worlds, are what ethnographers study. They are not ‘given’ and they

require detailed studies that reflect and respect their complexity. The notion that social realities

are socially constructed is something of a commonplace. But it deserves careful attention.

Constructionism (or constructivism) in general is a very important aspect of an ethnographic

understanding. Unfortunately, it is readily misunderstood and poorly applied. In particular, it is

too easy to assume that a constructionist analytic perspective implies that phenomena are ‘only’

constructed, or that they therefore lack any material substance. But there is nothing trivial

about constructions, and they have real embodiments and practical accomplishment. Likewise,

it is not the goal of constructionist analysis simply to conclude that things are socially

constructed, but to document how they are, with what resources, and with what consequences.

In other words, we ought to study how social realities are produced. Moreover, we need to

remind ourselves that notions of construction always imply the social. We are not dealing here

with private worlds or fantasies. Assumptions and activities in and about the world are

generated through socially shared beliefs, knowledge and conventions. Consequently, there is

a direct and necessary analytic parallel between our studies of social worlds and their

production and the detailed study of practical knowledge.

Just as realities are socially defined, so situations have their construction. The idea of the

definition of the situation is fundamental to our close analysis of social activities and events. But

if we subscribe to the view that situations are real insofar as they are defined as real, then that

does not mean that any or all such defining is arbitrary. Far from it: such defining is based on

shared or contested stocks of knowledge. They rest on the kinds of discursive and material

resources that social actors can mobilise. Situations and their definitions have to be sustained

through social action. Shared definitions depend on the intersubjective, mutual monitoring of

the parties to the situation. The nature of such interactional work depends on the frames of

reference that actors bring to bear and negotiate between themselves. There are degrees of

tentativeness or certainty concerning ‘what is occurring’. Is this serious or playful? Is it

wholeheartedly sincere? Aspects of interaction can be speculative, as it were: flirtation can be

an end in itself, or a speculative movement towards a different and more consequential

trajectory.

In other ways, social worlds are the products of social definition. There are no naturally-

occurring fields for us to study or for members to inhabit. The social world, the world around us

(what the phenomenologists call the Umwelt, which is only German for the same thing), is a

Page 2 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

shifting thing. It is defined by boundaries – physical and symbolic – that are themselves subject

to definition and negotiation. Boundaries are important in shaping the contours of everyday life.

Architectural boundaries, or geographical demarcations, can define spaces as sacred or

profane, frontstage or backstage, private or public. Such demarcations are consequential. In

this chapter, therefore, we shall examine some of the aspects that ethnographers need to take

on board. Given, as I have already said, that the ‘fields’ of fieldwork are not natural entities, we

need to pay close attention to how social worlds are identified, sustained and contested.

One can see that social constructions and definitions of the situation imply degrees of trust.

Trust – what Durkheim captured in writing about the non-contractual element of the contract –

is fundamental to the conduct of social action and interaction. It reflects the kind of practical

assumptions that we rely on unreflectingly. I place my trust in repertoires of experience and

reasoning that seem to work for most purposes. I place or withhold trust on the basis of what I

know about the kind of actor I am dealing with. I trust in certain procedures that I have relied on

before.

Social construction of reality

Constructionism has many roots and inspirations. It is convenient to think in terms of the key

work of Berger and Luckmann (1967). They really introduced to the English-speaking world key

aspects of the phenomenological movement and the work of authors like Alfred Schütz (1967).

It has also been associated especially closely with strands of thought in science and

technology studies (STS), social problems and criminology research, and the study of medical

knowledge. The STS strand was partly influenced by the work of Thomas Kuhn (1962), whose

book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions helped to establish a distinctively sociological or

anthropological view of scientific work and knowledge (Fuller 2000). The work of authors such

as Michel Foucault has also contributed, from a very different starting point, to a broadly

constructivist perspective on knowledge formation, cultural and scientific categories, and the

categorisation of social actors (e.g. Foucault 1973). It is also, more generically and loosely,

associated with interpretative social research. In the latter sense it does not, perhaps, have the

radical force of the pure phenomenological position. But viewed from a more general

sociological position, a constructivist perspective is a powerful way of comprehending how

everyday and specialist knowledge is produced, transmitted, used, validated and legitimated.

Such a view suspends our ordinary beliefs in the categories and contents of knowledge.

It is important to remember that social construction is proposed. In other words, constructivism

is not a claim that ‘realities’ can be conjured out of thin air purely by acts of will and imagination

by individual social actors. Moreover the fact that such activity is social means that it is rooted in

Page 3 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

shared cultural forms and resources. Constructs have history, they are embedded in traditions

and collective memories. The fact that they are ‘constructions’ should also alert us to the fact

that they require collective work to create or sustain them. So there is nothing mystical about

such ideas. On the contrary, they are thoroughly sociological and historical. Equally,

constructivists do not deny the material, concrete realities with which people work: an

exploration of the construction of diabetes or HIV/AIDS does nothing to wish them away or to

deny their physical consequences. We might equally think of the social production o f

phenomena, which gives us a yet more vivid reminder that we are talking about collective work

(in the broadest sense).

Constructionist analyses have been applied especially to social problems. Indeed, that is one of

the fields where such a perspective has flourished. One must be careful not to imply that a

‘problem’ is ‘only’ or ‘just’ a social construction. While constructionist analysis may demonstrate

and explain how a problem comes to be identified as such, how it is defined, how it is

measured, and its trajectory of development, our task is not to explain it away. It can be hard to

maintain strictly indifferent or symmetrical forms of analysis, but it is vital at least to try to

bracket any views as to the validity of any given construction. The constructionist perspective is

a methodological one, and not an ontological one. We are not in the business of vulgar

‘debunking’. By treating something as a social construction we are simply recognising that

there can be no social or cultural phenomenon that is independent of the processes of

recognition, description, or classification that render it as a social object in the first place. It is

too easy to slip into a mode of explanation that contrasts a social problem as a construction

(such as a moral panic) with some implied other state that is supposedly a true state of affairs.

Classics on the constructionist analyses of social problems include Spector and Kitsuse (1977),

Gusfield (1981) and Best (2004).

Some commentators and critics seem to think that the social analyst is only interested in

demonstrating that something – such as a diagnosis or a social problem – is a matter of social

construction. But most analysts working in this tradition would treat that as the starting point,

actually trying to explore how that work is done: Who makes decisions and imposes

interpretations? Based on what occupational or other culture? How do actors learn such

interpretative methods? What representations are used (e.g. media accounts, narratives,

images)? Some commentators – pro and contra constructivism – assume that the social

analyst’s aim is to undermine the assumptions, categories and decisions under investigation.

But it is not necessary or desirable to assume that constructivism is always critical or seeks to

belittle the authority of science and other expert fields. Indeed, it goes no further, in principle,

than demonstrating that science, technology, or medicine are human undertakings that share

Page 4 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

the same or similar processes that suffuse every other human, social activity. In many ways that

ought to endow the work and achievements of those domains of knowledge with a certain

nobility, rather than diminishing them. Equally, of course, it may call into question practitioners’

claims to superior ethical standards, the disinterested pursuit of knowledge, or selfless

devotion. Shortcomings are also human attributes, and ethics are context dependent.

In the same way, it is sometimes assumed that constructivists perversely deny the existence of

any material ‘reality’. This is not the case. It confuses an analytic stance with a normative one,

or a methodological stance with an ontological one. Constructivism is a methodological

perspective that requires the analyst to consider any and every aspect of knowledge as equally

‘socially constructed’. This is the principle of analytic symmetry. Similar criticisms are based on

what the critic assumes are such indisputably real phenomena that any questioning of them is

wrong-headed. Howard Becker (2014) provides a valuable (and characteristically readable)

rebuttal. ‘What about murder?’, he would hear from critics within criminology or socio-legal

studies: the implication being that murder must be a crime irrespective of any social-labelling

processes. ‘What about Mozart?’ critics ask, asserting that the composer was a genius by any

criteria. The fact that Mozart’s or Beethoven’s genius (DeNora 1995) is socially constructed

neither detracts from nor adds to the value of their music, but it does invite us to consider just

how aesthetic judgements are made, and by whom, using what criteria; it asks us to investigate

the role of impresarios, performers, critics and other cultural entrepreneurs; it forces us to

consider the contemporaries of such ‘geniuses’ to see why they have been relegated to the

margins of artistic canons. We might therefore end up understanding that artistic reputations

are not divorced from the social processes of production and reproduction, and are culturally

shaped by shared conventions. Indeed, we would readily broaden our analysis to include other

larger-than-life geniuses of the musical canon (such as Liszt or Paganini), while making

appropriate comparisons with contemporary celebrity culture.

There are many domains where the construction of categories of thought and action is central

to sociological or anthropological analysis: medicine and psychiatry; deviance, crime and law;

aesthetic judgements; belief systems. In a sense, without saying so, all of anthropology is

about the social construction of reality, as it emphasises the extent to which different cultures

can classify and manage the world – social and natural – in distinctive ways. Much of the

interactionist tradition in sociology is also concerned with social processes whereby facts,

decisions, categories, labels and the like are arrived at and implemented. This is paralleled by a

long-standing interest in the definition of the situation (discussed elsewhere in this chapter).

Key examples of research on constructivism are to be found in virtually all of the main fields of

empirical fieldwork. In medical settings, the construction of diagnoses and management

Page 5 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

decisions has been a major and recurrent theme. Contrasting approaches characterise the

field. On the one hand there are perspectives inspired by poststructuralist thought, associated

especially with the work of Foucault, stressing the historical and cultural specificity of clinical

categories and diagnoses (Foucault 1973). Medical knowledge is analysed as a projection of

medical power. Research from an interpretive or interactionist tradition on the other hand

stresses the local, practical accomplishment of diagnoses and management decisions. Medical

constructivism clearly does not try to wish away the realities of bodily pathology, but argues that

they can be construed/constructed in multiple ways, and that there is socially-distributed work

that goes into such constructions. Mol’s (2002) analysis of multiple professional versions of

physical phenomena is a key exemplar, while constructivist perspectives also treat lay persons’

understandings of bodily and health-related phenomena as worthy of careful analysis. (See

Atkinson and Gregory 2007 for a review of constructivism and medical knowledge.) In a similar

way, Science and Technology Studies (STS) is thoroughly constructivist in perspective; indeed

it can be argued that virtually all STS is constructivist as some level (though the field is

internally divided). Key ethnographic studies in the field certainly embody a constructivist

analytic perspective (e.g. Knorr-Cetina 1999).

Sometimes the relativism that seems to be embedded in a constructivist stance is presented as

a major problem for ethnographers. In the first place, we need to affirm constantly that

processes of knowledge production and construction are observable, empirical issues. It is

perfectly possible to observe and to document the processes whereby a diagnosis gets

assembled, a legal outcome is negotiated, a social problem is defined as such, or a team of

professionals puts together a case. Such empirical analysis is no different in kind or in principle

from any of the other social processes and encounters that one might observe in the course of

any field research. Do we ourselves escape from such processes? Of course not, we frame our

own arguments and our own texts in accordance with socially-shared conventions (Atkinson

1990).

For most practical research purposes, the ethnographer ought to suspend not just her or his

common-sense ideas about ‘realities’, but also bracket out the many debates and controversies

about constructionist (or constructivist) analysis itself. There are, after all, many empirical

issues that deserve attention irrespective of philosophy. For instance, there are many settings

where one needs and wants to ask: How are the facts produced? How are phenomena

classified and measured? How do actors describe what they see or hear, and how do they

describe what is going on? How do actors mobilise collectively to create preferred outcomes?

What methods are used to make a given social field relatively stable and predictable? How do

social actors interact so as to bring their perceptions of events into closer alignment? How is

Page 6 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

consensus established and maintained? And so on. We can and should answer such

questions in the field, without recourse to speculation on the nature of ‘reality’ beyond or prior

to our ethnographic inquiries (cf. Best 2008). As Maxwell (2012) and others have persuasively

argued, it is perfectly possible to sustain a (sophisticatedly) realist ontology together with a

constructivist epistemology. And in any case, it is also perfectly possible to observe and

document the processes whereby specific ‘realities’ (such as medical diagnoses or legal

judgements) are accomplished in equally real social settings. In other words, as ethnographers

we are not engaged in simply asserting that phenomena are socially constructed. We look

beyond that to ask ourselves how those tasks are accomplished, how realities are sustained, or

challenged; how they are justified; how they are reproduced. We also ask ourselves: What are

the consequences of such reality work? How are specific social realities enforced or

challenged? With what resources and skills are they accomplished? How are they maintained

through organisational practices, through everyday routines, or through common-sense

categories? For a guide to studies in this vein, see the collection of essays edited by Gubrium

and Holstein (2007).

Social worlds

The notion of a social world is associated especially with an analytic perspective derived from

the interactionist tradition of a second and third generation of ‘Chicago’ sociology (Fine 1995)

(which is not confined geographically to Chicago). It was explicated by Shibutani (1955) and

Strauss (1978b, 1982, 1984, 1993), among others. It has been applied to the analysis of

biomedicine and other science (e.g. Fujimura 1988; Clarke 1990), and occupational groups

(Kling and Gerson 1978). In general, social worlds are identified in terms of common or joint

activities, their actors bound together by a network of communication. In these and related

perspectives, there are several key social processes that guide the analysis: they are the

intersection of social worlds; segmentation into sub-worlds; and potential issues of authenticity

and legitimacy. In other words, in the interactionist style, the emphasis is on processes, and

competition. The analysis parallels the analysis of occupations and professions, as developed

by Everett Hughes. Here too we find an emphasis on professional segmentation, on

competition, on contested claims to legitimacy (Strauss, Schatzman, Bucher, Ehrlich and

Sabshin 1964).

In use, the idea is closely linked to the work of Howard Becker and is exemplified in his

monograph on art, appropriately called Art Worlds (Becker 1982). In the first place, this study

demonstrates a common trait of studies by Everett Hughes and his circle. Becker refuses any

approach that starts from an assumption that there is anything special or ‘consecrated’ about

the work of art. Moreover, the analytic focus is not just on the work of art in itself. Rather,

Page 7 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

Becker focuses on the social relations and division of labour that make possible any ‘art’ activity.

That complex of social relations and the variety of everyday work constitute the art world.

Hence, in the context of a discussion of the division of labour, Becker suggests:

Painters thus depend on manufacturers for canvas, stretchers, paint, and brushes; on

dealers, collectors and museum curators for exhibition space and financial support; on

critics and aestheticians for the rationale for what they do; on the state for the

patronage or even the advantageous tax laws which persuade collectors to buy works

and donate them to the public; on members of the public to respond to the work

emotionally; and on the other painters, contemporary and past, who created the

tradition which makes the backdrop against which their work makes sense. (1982: 13)

An obvious problem with this rather loose characterisation is that it can be extended almost

indefinitely. For instance, the commercial art world definitely needs specialist shippers and

couriers, who can deliver artworks safely and promptly to galleries and collectors; specialist

insurance companies who will insure individual works or art collections; event organisers and

caterers for gallery and exhibition openings; publishers for art monographs; printers for

exhibition catalogues; magazines in which exhibitions and openings can be advertised and

reviewed. And so on. There is an obvious danger of lumping together a vastly disparate variety

of actors and activities and declaring it a ‘social world’, simply because they are all engaged in

a set of activities with a common name (in this case ‘art’). It is clear that one can only develop

such an idea with real analytic bite if it is grounded in empirical research on actual social

relations. In the case of ‘art’ worlds, therefore, one needs detailed ethnographic studies that

preserve the specificity of the art and the concrete social relations that constitute a possible

‘world’. One such exemplar is Gary Alan Fine’s study of naïve American art and its collectors

(Fine 2004), or his monograph on mushroom collectors (Fine 1998).

Becker himself illuminates his approach in a useful and telling interview (Becker and Pessin

2006). There he and his interviewer contrast Becker’s approach to ‘worlds’ with Bourdieu’s

notion of ‘fields’ (e.g. Bourdieu 1993). Perhaps the distinction seems like academic nit-picking.

On the other hand, it helps to clarify what is going on here. Becker suggests that Bourdieu

uses the idea of a field as a metaphor to capture impersonal ‘forces’. (I think that this is entirely

congruent with the French anthropology and sociology that permeated the intellectual

background to Bourdieu’s work.) It owes much to structuralism (broadly defined), even when

Bourdieu claims to be reacting against it. The field is a site of power and domination, of

competition for scarce resources, and of symbolic boundaries of inclusion and exclusion. In

sharp contrast Becker says that his notion of a social world is essentially a descriptive term,

and not an abstract metaphor. In the course of the interview he says,

Page 8 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

A ‘world’ is thus an ensemble of people who do something together. The action of

each is not determined by something like the ‘global structure’ of the world in question

but by the specific motivations of each of the participants, any of whom might ‘do

something different’, create new responses to new situations. In these conditions,

what they do together results from arrangements about which the least one can say is

that they are never entirely predictable. (2006: 280)

In other words, as Becker paraphrases himself immediately after, a social world ‘consists of real

people who are trying to get things done, largely by getting other people to do things that will

assist them in their project’ (ibid.).

These two poles – the abstract, metaphorical and the concretely descriptive – capture a

recurrent tension in the conduct and reportage of ethnographic fieldwork. The tensions within

as well as between the two positions are also telling. While Bourdieu seems to Becker to drain

the actual interpersonal work out of his ‘field’, Becker seems to me to remove from his ‘world’

the specificity that makes it a world (or anything) in the first place. His approach leaves a

residual paradox: in the complete absence of any discussion of aesthetics or values, one

remains mystified as to quite why the artist would devote years of her or his time – with no

guaranteed material reward – to making artworks of any kind. After all, art may well be work.

But is it always work like any other? Indeed, is any work just work like any other? If we confine

ourselves to the most generic of analytic categories, then we are always in danger of losing the

distinctive ‘whatness’ – the quiddity – of what is done and what is produced. Because, if one

says that a social world is defined just in terms of people doing things, then there are few

grounds for identifying anything in particular. Indeed, there is a similar argument made in

relation to work that Becker himself collaborated on (Becker, Geer, Hughes and Strauss 1961).

That classic Chicago School study of socialisation in a medical school borrowed ideas from

industrial sociology in order to account for student culture, and the collective strategies that

medical students negotiated among themselves in order to cope with the considerable –

sometimes overwhelming – demands of medical school. What Becker and his colleagues

describe is surely accurate. There is little doubt as to the significance of phenomena like

student culture and the hidden curriculum in many educational contexts. In this sociological

account, the content of the curriculum, and the manner of its pedagogy, remain invisible to the

reader. Those medical students do not seem to be learning anything in particular. You could

say the same things about coping mechanisms in virtually any institution, and there is rather

little in the monograph to hint at what forms of medical knowledge are being reproduced, and

what versions of medical practice are being enacted in the classrooms and on the floors of the

Page 9 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

teaching hospitals (Atkinson 1981).

In other words, any use of social worlds needs to be informed by a degree of specificity. The

boundaries of such a world may well be permeable, but in the absence of some principled

notion of where to stop, virtually anything and anybody could be brought into the bounds of

any social world. Likewise, one needs a strong sense of the content of a given social world – its

particularity – if one is to avoid the sociological commonplace of making each one like every

other. So the task for the ethnographer is not merely to explore a given social world. It includes

the need to analyse what makes it a social world. What symbolic boundaries are used to

delineate such a domain? (If indeed it is a meaningful entity for the participants.) Do social

actors make distinctions between themselves and other social worlds? What are the elements

that comprise this world? What are its distinctive cultural forms and contents? What are the

social relations that define and constitute that world? Equally, we must be careful not just to

assume that there must be a ‘social world’ that corresponds to the particular phenomenon we

choose to look at and participate in.

Defining the situation

This is another of the sociological classics that are often invoked in the analysis of social

encounters and organisations. It derives from a famous dictum by W.I. Thomas, one of the key

figures in the development of the Chicago School of sociology (Thomas 1923). In that

remarkably early formulation, Thomas first suggested that situations are real insofar as they are

defined as real and are real in their consequences. Now the dictum is open to over-

simplification and misunderstanding, not least because it is too often quoted in isolation, and

without consideration of its thoroughly sociological inspiration and applications. The concept is

analogous to the social construction of reality; the two ideas represent a convergence of

interactionist and phenomenological traditions. Neither is intended to imply that ‘reality’ can be

conjured up out of thin air, or that definitions can be created by acts of will alone. So it is not a

good idea to invoke such an idea carelessly, or as if it referred only to individuals’ interpretations

and wishes. Defining reality is a complex social process (DeNora 2014).

We have to start not just with the ‘definition’, but with the ‘situation’. It is easy to overlook the

fact that for a definition or definitions to be in play there must be a situation as well. So here a

situation must mean something socially and analytically specific. It requires two or more actors

to be engaged in some degree of mutual attention, undertaking joint activity. The situation is,

therefore, an intersubjective event. It does not comprise two or more separate individuals, each

free to impose a definition. Definitions have to be grounded in shared and negotiated activity

(even if one party is manipulating the others). In other words, there is nothing arbitrary about

Page 10 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

definitions of the situation, except insofar as all social events are conventional and that culture

has an arbitrary aspect to it. Situations, we are reminded, are real insofar as they are real in

their consequences. Again, this is not a matter of whimsical or idiosyncratic ideas somehow

being conjured into life. It means that situations are only real if actors act on the basis of that

definition. Consequences can refer to a wide range of possible outcomes – including of course

further situations and further negotiation. The definition of the situation is, it follows, a

profoundly social concept, owing nothing to individualism. It also departs from the idea of a

Sociology of the Absurd (Lyman and Scott 1970), which does emphasise the arbitrary formation

of social realities.

The idea of the definition of the situation, beyond Thomas’s original dictum, owes something to

the interactionist tradition, to phenomenology and to ethnomethodology. As Perinbanayagam

(1974) points out, these are not always mutually compatible, and a degree of conceptual

muddle is always possible. The important task for empirical researchers is to employ the idea(s)

in genuinely sociological ways. That is, through a recognition that situations are defined and

sustained in interaction between social actors who are actively engaged in sustained

interpersonal work. It is always an empirical issue as to how and whether a sustained definition

is achieved, by whom. These are not necessarily cut-and-dried: it is possible for a state of

pervasive ambiguity to hinder any such resolution (Ball-Rokeach 1973).

A potentially misleading example is the monograph by McHugh (1968) that elaborates a

demonstration by Garfinkel (1967). It is based on a famous experiment. It shared features with

psychological experiments on yielding and conformity. The participants were informed that they

were receiving an experimental form of counselling: they could ask questions to which they

would receive answers. The nature of the experimental treatment lay in the fact that the

answers (Yes or No) were randomly assigned and bore no actual relationship to the questions

as posed. Asked to reflect on the questions and answers, the participants (‘experimental

subjects’ as they might be termed) did their very best to turn the random answers to their

questions into some semblance of coherence. They interpreted the answers as responses to

the questions, and tried to create coherence out of the absurd situation. This is, however, a

flawed exercise, although it is illuminating up to a point. There was no interaction between the

‘conversationalists’, and there was, therefore, no joint negotiation of a shared definition of the

situation. Moreover, the definition of the situation that was in play was one imposed by the

experimenters. The participants were, after all, told that they were participating in an

experiment. Everything they did was done in accordance with that definition. Their sense-

making efforts were done in order to try to bring the random answers into line with the a priori

definition. The experiment was illuminating up to a point, but in the final analysis very limited.

Page 11 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

As Perinbanayagam observed, ‘… the only definition of the situation which could possibly have

occurred was that of someone doing an experiment about therapeutic practices, and that

occurred in spite of the experimental procedures used’ (1974: 529). So perhaps the ‘experiment’

demonstrated that the participants responded to the imposed definition, but not in the way that

McHugh – and Harold Garfinkel – quite intended.

Further, such an imposed definition can rob the idea of its real significance. That is, the sense

that definitions can be fragile, plastic, changing, and even contested. One of the key aspects of

situations is the possibility that the different parties to an encounter may harbour and act on

different sets of assumptions and perceptions. What is behaviourally ‘the same’ event may

contain contrasting meanings for different participants. Hospital and laboratory fieldwork at

Cardiff, for instance, has suggested that consultations at ‘the same’ hospital clinic for

neurological conditions could be defined primarily as a therapeutic or diagnostic event by

patients and their partners, while it was primarily a research-oriented event for the clinical

researchers who conducted it (Lewis, Hughes and Atkinson 2014). Moreover, we really ought to

think in terms of a more continuous process – defining the situation – rather than a single

outcome (Stone and Farberman 1970). That can be a process of negotiation, or a matter of

differential power. Indeed, one of the key aspects of the micro-politics of encounters is the

ability of one or more parties to impose their preferred definition, at least in terms of the

practical outcomes and consequences. Equally, as Altheide (2000) argues, identity and the

definition of the situation are closely related analytically. He draws attention to the extent to

which versions of ‘identity’ can be divorced from the interactional accomplishment of encounters

and situations, and associated with almost essentialised social categories (race, class, gender,

sexual orientation, etc.).

Frame-analysis builds on the idea of the definition of the situation. Framing captures some of

the underlying dimensions that inform actors’ (and analysts’) grasp of what kind of a situation is

being enacted, and therefore what range of behaviours is situationally appropriate. Framing

can, for instance, relate to the degrees of seriousness and intent that are implied. A key

example might be the difference between a situation that is being enacted ‘for real’ and a

rehearsal of such a situation, or a dramatic representation of it. The significance of actions

performed under such contrasting circumstances is clear. The expression of emotion under

conditions of, say, theatrical performance is very different from that under conditions of ordinary,

mundane reality. A ‘stage kiss’ between actors has very different import from a kiss between

lovers. (Of course, when pairs of famous actors such as Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton or

Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh become equally famous or notorious lovers, the frames can

become blurred and the frisson of excitement correspondingly enhanced.)

Page 12 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

Consequently, framing can have far-reaching consequences for the management of encounters

and situations. Goffman (1974) provides the most comprehensive enumeration of framings. It is

part of his career-long exploration of social encounters and their conventions. We have to be

careful not to use the idea in a circular fashion. It is not very helpful to suggest that actors are

interpreting a situation as a teasing or playful one because it is framed as such, and equally to

say it is framed as a tease because that is the way they are acting. In other words, we need to

be able to identify how actors are accomplishing something like framing. Indeed, the analytic

point for the observer is precisely how actors construct and convey the behavioural and

discursive cues to demarcate levels or layers of reality work. Goffman himself refers to keys in

such analytic contexts. Framings have a great deal to do with the sort of sincerity and

commitment that actors invest in encounters. Gonos (1977) suggests that Goffman’s frame

analysis distinguishes his work most starkly from that of the interactionists, insofar as it defines

an essentially structural approach to situations, as opposed to the under-determined version of

the symbolic interactionists. Frames are, Gonos argues, relatively stable, based on cultural

codes and conventions that are oriented to by participants. Gonos himself used frame analysis

in his (1976) ethnographic study of go-go dancing.

To some extent, the general idea parallels the analysis of vocabularies of motive. The latter

refers to motivational framings that provide ways of making sense of action, by attributing

appropriate motives to the actors. It also relates to Geertz’s use of ‘thick description’, in that the

latter refers to the cultural meanings that inform the performance and interpretation of a given

action, or indeed distinguish inadvertent behaviour from purposeful action (Geertz 1973). In

other words, if we want to make sense of a series of activities, or a given interaction, then we

need to know how it is framed, what behaviours are appropriate, and therefore how it is being

understood by the participants. We shall need to bear in mind that the participants themselves

may entertain competing frames: a good deal of situational comedy, from Plautus and Terence

onwards through Goldoni, derives from such ambiguities and misalignments. Self-deprecation

can be embarrassingly misinterpreted if the framing is not visible to all parties, as can irony. If

something ironic is interpreted literally, then profound misunderstandings can ensue,

necessitating a great deal of repair. Participants can use possible ambiguities in framing to

strategic effect. An attempt at romantic intimacy that is unsuccessful can be repaired by a claim

that it was a ‘tease’, while of course the other party can pretend not to have noticed, or to have

treated it as less than serious all along.

Documentary realities

Ethnographers need to pay close attention to the creation, circulation and use of documents of

all sorts. As Watson (2009) points out, there is, in contemporary society, a plethora of texts in

Page 13 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

everyday life: text messages, tattoos, tickets, receipts, road markings and street signs,

newspapers, advertisements and hoardings, are just some of them. Furthermore, there are

specialised, professional and bureaucratic texts in great number: records, case files,

regulations and codes of practice, organisational charts. There are archives of all sorts, from

personal collections to national repositories. The ‘file’ is a pervasive cultural product (Hull 2003,

2006). In principle, any and all of these documentary materials can find their place in

ethnographic studies. As with any and every form of artefact and text, ethnographers should

not assume that such materials are privileged sources of information, or that documentary

evidence trumps other forms, such as oral testimony. Rather, we recognise that documentary or

textual sources are among the means whereby social realities can get constructed, or whereby

identities, biographies and labels are crystallised (Prior 2003). Documentary records and

artefacts are such a pervasive feature of modern social institutions that they deserve close

attention in multiple ethnographic contexts (Riles 2006; Atkinson and Coffey 2011).

Bureaucratic textual formats are among the ways in which complex social worlds are

transmuted into standardised forms. The dual meanings of ‘forms’ in this context is a guiding

metaphor: paper or online forms can provide standardised forms or formats through which

bureaucratic realities are sustained and reproduced. While members of an organisation may

not follow bureaucratic rules ‘to the letter’, documentary representations can be invoked to

justify and legitimise courses of action. Organisational records do not necessarily provide

transparent representations of ‘what happened’. Their construction and use depend upon local

organisational and professional knowledge. This was the major issue identified by Harold

Garfinkel (1967) in his discussion of ‘good organisational reasons for bad clinical records’. He

pointed out that hospital records are written and read in the context of professional background

assumptions concerning the kinds of work and the sort of judgements that inform them.

Consequently, an ethnographic understanding of the organisation of work needs to take

account of such record-making, and studies of records need to examine the background

conventions that inform them.

Record-keeping and record-making can therefore be central analytic topics for workplace and

similar kinds of ethnography. Medical records have provided fruitful topics in this regard.

Clinical case-notes are repositories of information about patients. They are among the

mechanisms whereby persons are transformed into patients, and in turn turned into ‘cases’.

Indeed, the processes whereby medical records are created are among the concrete,

observable practices whereby realities (such as diagnoses and management decisions) are

constructed (Rees 1981; Bloor 1991; Berg 1996). Such records are, of course, often the

outcomes of other, prior texts and form part of a circuit of textual artefacts (Hak 1992). The

Page 14 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

written record, moreover, can be granted greater credibility and weight than other sources of

knowledge, evidence or authority. The document can be made to support the ‘bare facts’, as

opposed to opinion or recollection. (See Scott 1990.)

Fincham, Langer, Scourfield and Shiner (2011) offer a distinctive use of documentary sources,

applied to one of sociology’s classic topics – suicide. Although theirs is not an ethnographic

study, it provides a valuable exemplar for researchers more generally, working in organisational

settings, and studying processes of typification or classification. They treat documentary

sources as topics and resources for analysis. In the course of their ‘sociological autopsy’, they

examine a range of files and documents (including suicide notes) in demonstrating the variety

of identities attributed to the deceased. In detailed readings of the suicide notes in particular,

they respect their constructed nature while drawing conclusions concerning causal explanation.

Paying close attention to documentary realities is a feature of institutional ethnography, a s

practised by Dorothy Smith and her colleagues (e.g. Smith 2005; Smith and Turner 2014), and

they put considerable emphasis on documentary materials. Smith, in the course of outlining a

form of public sociology, draws attention to the ways in which institutional texts remove agency,

depersonalising regimes of regulation. An ethnography that is attentive to textual regimes

shows how they co-ordinate action. The ethnographies explore what are called textually-

mediated activity. While one can question the actual novelty or distinctiveness of this approach,

it leads to an interesting variety of ethnographies that document the local practices of

engagement with texts (not all of which are ‘institutional’ in the conventional sense). They range

from a musician’s work with the score of a concerto (Warren 2001) to texts and local-

government planning (Turner 1995), or the regulation of organic farming (Wagner 2014).

Ethnographies of science and technology are prime sites for textual practices. The outcomes of

routine scientific work are ‘results’, while those of revolutionary science are ‘discoveries’, but

both depend on the production of textual representations of that science. Those texts often take

the form of scientific papers, which themselves follow typical formats, to the effect that the

agency of scientists’ work is rendered invisible, and the nature of scientific knowledge uniform.

The conventions of scientific writing have been examined for their textual and rhetorical devices

(e.g. Myers 1990), while ethnographies of laboratory life include accounts of how scientific work

is transmuted into such texts and representations. In a classic exploration of laboratory realities,

Latour and Woolgar (1986) discuss the production and circulation of such artefacts, which they

call immutable mobiles: they turn the local production of knowledge into artefacts that can be

detached from their local context. Moreover, the textual format of scientific reports and papers

has evolved over time and is now thoroughly taken for granted. Its conventions appear to be

‘natural’ modes of expression. Scientific documents therefore construct a particular version of

Page 15 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

what science is and how it is accomplished, not just how it is reported. The conventional, highly

condensed scientific paper removes agency. The use of the passive voice is highly

characteristic of the natural sciences (and sometimes aped in the social sciences too, often with

deleterious consequences). These documents are dependent on a high level of shared

knowledge between author(s) and reader(s), since a very great deal of background

assumptions is assumed and left unspoken.

The competent reading and use of texts is often dependent on elements of trust. Readers and

writers trust in each other, for practical purposes of putting texts to work. Institutional and

bureaucratic texts are often insufficient in themselves without some background knowledge of

who wrote them and what went into their construction. For instance, as Stephens, Lewis and

Atkinson (2013) point out, processes of certification and accreditation – in this case in a

laboratory – can go on indefinitely, with more and more systems of regulation that monitor other

regulatory procedures. In practice, such an infinite regress is avoided on the basis that

regulators know whom they regulate, and ultimately a degree of trust is necessary. Wagner’s

(2014) discussion of certifying organic farming is a parallel case, where local and personal

knowledge mediate regulation, just as regulatory texts mediate social relations.

Ethnographers, therefore, need to ensure that literate cultures are not inadvertently

(mis)represented as if they were entirely oral, by neglecting written texts, their creation,

circulation and use. Equally, we need to avoid the everyday assumption that documents are in

some sense more factual or reliable sources of evidence than any others. Consequently,

‘triangulation’ should not mean checking data such as oral testimony and accounts against ‘the

facts’ enshrined in documentary sources. Equally, we need to recognise that textual formats

and the routines used to construct them can have an active role in constituting social realities,

in co-ordinating activity and in generating orderly conduct. That does not mean that they have

no referential value and it is far from necessary to take a purely constructivist perspective that

insists that documents can only be studied as artefacts, with no evidential value for the

ethnographer. What is crucial, however, is the recognition that documentary realities are

themselves social products, and even when they appear to be plain statements of fact, they are

constructed, read and interpreted in that way. There is never a transparent relationship

between a document and what it reports. Documents mediate. They are produced and

consumed in accordance with cultural conventions. Their formats can actually generate the

forms of reality that they report. There is no antithesis between documentary analysis and

ethnographic fieldwork, provided we take care to examine the practicalities of document use.

Documentary sources are, therefore, not simply an analytic resource for the ethnographer.

They are potential topics for analytic attention. Processes and routines of record-making and

Page 16 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

record-keeping are important aspects of contemporary culture (Riles 2006). Audit culture, for

instance, is possible only by virtue of documentary work. In anticipation of audit, members of

organisations are required to create documentary archives and paper trails that anticipate

internal and external scrutiny in a foreseeable future. As a consequence, the formats and

contents of such documents define the past and project possible futures. Like all versions of

documentary reality, they depend on record-makers and record-users having a level of shared

understanding and background knowledge. No document can entirely determine how it is read

and interpreted, and so readers must bring to them local, situated knowledge, and read into

those documents background assumptions and expectations. Consequently, it is the job of the

ethnographer to examine the everyday realities of documentary action. Writing and reading,

storing and consulting documents are everyday work activities. Interpreting documents is

grounded in often complex assumptions concerning those routines and realities. Hull (2003,

2006), based on an anthropological ethnography of bureaucracy in Islamabad, suggests that

contemporary regulation and governance are governed by what he calls ‘graphic artefacts’ –

files, maps, letters, reports, and office manuals. Nowadays, of course, such documentary forms

are frequently physically in digital form rather than physically available on paper or in filing

cabinets. The principle is the same irrespective of whether records are virtual or material.

Boundaries

Social scientists are given to creating categories and boundaries, and so too are social actors.

The classifications of cultural categories are not the sole preserve of anthropologists and

sociologists (Ryen and Silverman 2000). There are many ways in which an ethnographic

fieldworker needs to pay attention to boundaries, physical and symbolic. Physical boundaries

define space and demarcate domains of legitimate participation, forms of activity, and spheres

of significance. Such boundaries shape and define the performative architecture of built

environments, such as hospitals, prisons, laboratories (Thrift 2006). They separate sterile

spaces from dirty or polluting ones. They segregate inmates from one another, from staff, from

the outside world (Stephens, Glasner and Atkinson 2008). They can separate the sacred from

the profane. They demarcate backstage regions from frontstage regions. The total institution

(Goffman 1961) is largely defined by its boundaries. External boundaries, such as prison walls,

define and circumscribe the institution, while internal divisions define spaces of sequestration,

of association, of movement between otherwise separate spaces, and so on. Within an

institution, such as a hospital, boundaries define the distinctive shape of the clinic (in the

broadest sense) – the arrangement of the wards, the divisions between specialties. Historically,

the physical arrangement of the hospital has inscribed aspects of medical knowledge, and the

professional division of labour.

Page 17 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

Boundaries do not enact such distinctions and differentiations independent of the significance

attributed to them. In that sense, all boundaries are symbolic. Equally, of course, it is possible

to have symbolic boundaries that are not directly embodied in physical walls or barriers.

Symbolic boundaries demarcate fields of expert knowledge, academic specialties, cultural

domains, and the like. Boundaries are established and maintained by subtle codes of

distinction, such as the cultural codes that reflect differences in social class and status, or that

enact gender and ethnic differences. Such symbolic boundaries can, therefore, help to

enshrine the systems of cultural classification, as described classically by Durkheim and Mauss

(1963), and as explored subsequently (Bloor 1982). Analyses include cosmologies reflected in

social and physical arrangements. The symbolic arrangements of dwellings and settlements is

a classic and recurrent theme in anthropological studies. They include the symbolic and

physical barriers between the home and the street, notably in studies of Mediterranean

societies. The internal divisions and demarcations within the household, such as those that

separate male and female spheres of influence, or that separate domestic servants from their

mistresses and masters, are also among recurrent motifs. For a classic description, see

Bourdieu’s (1971) description of the Berber household; see also Delamont’s (1995) general

account of boundaries and segregation in European cities.

Academic and other intellectual fields are characterised by symbolic boundaries. What we

conventionally think of as academic disciplines or curriculum subjects embody such bounded

domains. The divisions are arbitrary, to the extent to which there are in principle many ways of

dividing up all the possible versions of human knowledge. (That does not mean that they are

entirely arbitrary or whimsical: they have referential or representational relations with the world.)

They are forms of cosmology, in that they help to define not just how the world is, but how the

world ought to be. The boundaries that such cosmologies define are thus treated as normative,

and are often patrolled and policed. The relative strength of symbolic boundaries in academic

fields helps to define the kind of curriculum that is pursued. Bernstein’s sociology of academic

knowledge includes a consideration of such classification: ‘pure’ academic subjects have

strong symbolic boundaries, while interdisciplinary studies have weaker, more permeable

membranes between knowledge domains. In a rather similar vein, Bourdieu’s sociology of

culture stresses the kind of horizontal and vertical boundaries that help to define cultural

competence and taste. Culture is stratified, reflecting social stratification, and the boundaries

between ‘high’ (consecrated) culture and ‘popular’ or ‘vulgar’ (profane) culture can be

rigorously enforced.

In turn analysis of these symbolic boundaries and their management reflects the

anthropological analysis of cultural systems pioneered by Durkheim and Mauss who related

Page 18 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

cultural classifications to systems of social division. The treatment of anomalies of such

systems – objects or persons that transgress boundaries – was developed by Mary Douglas

(1966). Her analysis of pollution emphasises the extent to which ‘dirt’ is matter out of place.

Consequently hybrids, monsters and anomalies can be highly threatening to the established

cultural order. In an analysis of newly emergent academic specialisms, Lewis, Bartlett and

Atkinson (2016) show that bioinformatics experts can be troublesome, being ‘hybrid’ and

anomalous, somewhere between biology and computer science. In a similar vein, Fisher and

Atkinson-Grosjean (2002) consider the role of actors who mediate between university research

and industry: they can be marginal or liminal to both domains. Harvey and Chrisman (1998)

use the idea of boundary objects to explore how GIS technology mediates and migrates

between different groups. Of course, over time cosmologies and organisations can change, so

that new specialisms and categories emerge and become part of the established order,

throwing up new anomalies in their turn. Symbolic boundaries can also be policed by

professionals and practitioners who seek to preserve orthodoxies. Scientific paradigms (Kuhn

1962) are sustained in part by boundary-work on the part of promoters of the taken-for-granted

order of normal science at any given time, while mavericks and innovators can be excluded.

Boundaries can be discursive constructs. Accounts and accounting devices include the use of

contrastive rhetoric. People contrast what ‘the others’ did (poorly) with what ‘I’ or ‘we’ did

(better). Medical professionals in elite hospitals, for instance, construct part of their case

narratives around the contrast between what was done or not done by primary-care medics, or

at peripheral hospitals with the shrewd and competent diagnosis and treatment that they

themselves initiated as soon as the patient came into their care (Atkinson 1995). Likewise,

academics construct their own discipline by discursive contrasts with others. Their own

discipline can be defined and defended by comparing it with others: more practical, more

scientific and so on. These boundaries are thus created and reinforced through practitioners’

accounting methods (Delamont, Atkinson and Parry 2000). As Gieryn (1995, 1999) suggests,

the boundaries between ‘science’ and ‘non-science’ are discursively produced through

boundary-work, rather than being based on essential characteristics of science itself.

So an analysis of boundaries – physical, symbolic, discursive – can be a productive strategy in

understanding the cosmologies of local cultures, such as those of occupational groups. It is, of

course, always important to remind oneself that such boundaries and distinctions are never

entirely fixed or impermeable. Boundaries can be crossed: depending on the circumstance,

such border crossings can be acts of transgression and deviance, or of pioneering heroism.

Hybrid anomalies can evolve into new entities, mavericks can become the pioneers of new

orders. But those new arrangements will be defined by new symbolic markers and boundaries.

Page 19 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

Boundary crossings can be opportunities for adaptation and learning (Akkerman and Bakker

2011). They explore various ways in which cultural discontinuities can provide resources for the

development of identities and strategies. They identify: identification, which concerns learning

about different practices; co-ordination, the creation of cooperative exchanges across

boundaries; reflection, the capacity to expand one’s perspectives; transformation, which

concerns the emergence of new practices. In many ways, of course, such constructive border

crossings parallel the work of the ethnographer, since anthropological and sociological

fieldwork is based on cultural learning derived from the exploration of an unfamiliar social

world. See also Wegener (2014) on parallels between ethnography and border crossings, in a

study of educational and care settings.

Boundary objects have become a significant analytic topic, notably but not exclusively in

Science and Technology Studies (Star and Griesemer 1989). In that context, boundary objects

inhabit more than one social domain, such as a field of specialisation. They are relatively

plastic, and can thus have different values for the actors who use them. But they are robust

enough to retain meaning in two or more domains. Like a lot of concepts of the middle-range,

boundary objects can seem an over-used idea. People have identified boundary objects in

many contexts, and the concept can seem played out. As with so many concepts of the middle-

range, it is important to retain a sense of precision and purpose in using these ideas.

Boundaries can be found all over the place, and virtually anything can be a boundary object.

The solution is not to abandon such ideas altogether, but to use them with some purpose, and

with clear analytic point. Simply declaring something to be a boundary object is not a very

penetrating analysis in and of itself.

Fieldwork, therefore, is permeated by issues of boundary. Indeed, ‘fields’ are not given to us as

natural kinds (cf. Amit 2000). What we describe as social worlds, field sites, or social networks,

are ‘bounded’ only in the sense that there are social or cultural boundaries in play. Likewise,

the categories and classes we use (such as diagnostic categories) are locally defined by the

symbolic boundaries that are placed around them. Boundaries, therefore, are neither given nor

fixed. They are constantly in the process of being defined, refined and negotiated through the

everyday social activities of social actors and collectivities. Our analytic interests therefore go

beyond just negotiating those boundaries ourselves in pursuit of research access, but in

developing a sustained and detailed understanding of the interpersonal processes whereby

boundaries are defined, transgressed, patrolled and celebrated. We need to be attentive to the

segmentation of our chosen research settings, and the ways in which such segmentation is

realised.

Page 20 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

Conclusion

As we have seen, there is ample opportunity for misapprehensions concerning ‘definitions of

reality’. It can too often appear as if constructivist analysts were in denial concerning the very

existence of an external reality that impinges on everyday social activity. Vulgar criticisms imply

that we believe realities to be conjured up out of thin air, as if anything and everything could be

invented from scratch. That is not the case. Analysis of social reality is, by contrast, at the very

heart of any sociology or anthropology that is methodologically and theoretically sensitive. As I

have emphasised, in the first place, we are interested in social constructions. For some

purposes, it might be more productive to think of the social production of reality. Such

terminology might help to reinforce the extent to which we are dealing with collective social

activity. Reality production is collaborative work. It is based on collective, interactive activity. It is

generated from shared cultural resources.

Ethnographic analysis, therefore, is not aimed simply at demonstrating that realities are socially

produced, but – much more fundamentally – on how that is accomplished. We have to ask

ourselves repeatedly how social actors engage with one another in order to sustain shared

understandings and commitments. We ask ourselves what resources those actors bring to any

such work. Equally, we must remember that we are dealing with definitions of the situation. So

the situation becomes a possible unit of analysis, and situations are self-evidently social in

character. ‘Situations’, in this sense, are not given, they are made to happen by their

participants. They are defined in part by the boundaries that encompass them. As we have

seen, such boundaries may be physical, but – more importantly – they are always symbolic.

And in the same vein, situations may be framed in accordance with socially-shared conventions

of orderly conduct. They are, therefore, thoroughly social in character, and they display their

cultural basis.

For the ethnographer, therefore, there are lessons. We should not take on trust the kinds of

situations and definitions we observe and participate in. We need to pay close analytic attention

to the methods and means whereby situations and realities are co-produced by social actors.

This is not a matter of intuition on our part. Social actors observably work at making realities

possible, and they use cultural resources that are open to us for discovery. Such a perspective

does not mean that all situations are unambiguous or that consensus reigns. Indeed, one of

our key analytic issues involves the recognition that there may be competing realities in play,

and confusions or conflicts that arise.

We do not, however, come to grips with these social phenomena without the fine-grained

observation of what social actors actually do (including what they say). This therefore leads us

Page 21 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

SAGE SAGE Research Methods

©2017 SAGE Publications, Ltd.. All Rights Reserved.

to the subject matter of the next chapter: social encounters. The emphasis among many

qualitative researchers today on extended interviews can all too easily lead us away from the

fundamental building blocks of everyday life. An ethnographic analysis of interaction –

conversations, pedagogic events, sporting contests, business meetings, conferences,

consultations with professionals – is vital if we are to come to grips with the remarkable variety

of social action, and its organisational properties.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781473982741.n2

Page 22 of 22 Thinking Ethnographically

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Vocabulary Ingles PDFDocument4 pagesVocabulary Ingles PDFRed YouTubePas encore d'évaluation

- DLP For Inquiries, Investigations and ImmersionDocument5 pagesDLP For Inquiries, Investigations and Immersionolive baon71% (7)

- Brochure RevisedDocument2 pagesBrochure Revisedapi-434089240Pas encore d'évaluation

- Paetep Observation 12-5Document7 pagesPaetep Observation 12-5api-312265721Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fr. Lawrence Smith - Distributism For DorothyDocument520 pagesFr. Lawrence Smith - Distributism For DorothyLuiza CristinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Women, Ethnicity and Empowerment - Towards Transversal PoliticsDocument24 pagesWomen, Ethnicity and Empowerment - Towards Transversal PoliticsAlejandra Feijóo CarmonaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rome's AccomplishmentsDocument13 pagesRome's Accomplishmentskyawt kayPas encore d'évaluation

- CS - EN1112A EAPP Ia C 7Document9 pagesCS - EN1112A EAPP Ia C 7LG NiegasPas encore d'évaluation

- Is Imitation The New Standard in Apparel Industry?Document6 pagesIs Imitation The New Standard in Apparel Industry?em-techPas encore d'évaluation

- Tableau WhitePaper US47605621 FINAL-2Document21 pagesTableau WhitePaper US47605621 FINAL-2Ashutosh GaurPas encore d'évaluation

- My Report Role of Transparency in School AdministrationDocument31 pagesMy Report Role of Transparency in School AdministrationHanna Shen de OcampoPas encore d'évaluation

- WGST 303 Spring 2014 SyllabusDocument6 pagesWGST 303 Spring 2014 SyllabusSara P. DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- An Inspector Calls Essay Guide PDFDocument12 pagesAn Inspector Calls Essay Guide PDFjessicaPas encore d'évaluation

- B.ed Curriculum 2015-17Document70 pagesB.ed Curriculum 2015-17Bullet SarkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Asma Final PaperDocument24 pagesAsma Final Paperapi-225224192Pas encore d'évaluation

- J S Mill, Representative Govt.Document7 pagesJ S Mill, Representative Govt.Ujum Moa100% (2)

- Alex Klaasse Resume 24 June 2015Document1 pageAlex Klaasse Resume 24 June 2015api-317449980Pas encore d'évaluation

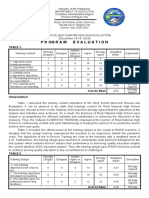

- Program Evaluation: Table 1Document3 pagesProgram Evaluation: Table 1Joel HinayPas encore d'évaluation

- Tanishq The Indian Wedding JewellerDocument3 pagesTanishq The Indian Wedding Jewelleragga1111Pas encore d'évaluation

- Public Interest Litigation in IndiaDocument13 pagesPublic Interest Litigation in IndiaGlobal Justice AcademyPas encore d'évaluation

- To His Coy MistressDocument7 pagesTo His Coy Mistressmostafa father100% (1)

- Postcolonial Studies in TaiwanDocument15 pagesPostcolonial Studies in TaiwanshengchihsuPas encore d'évaluation

- Facilitation Form: Skill Development Council PeshawarDocument3 pagesFacilitation Form: Skill Development Council Peshawarmuhaamad sajjad100% (1)

- Writing Skills Practice: An Invitation - Exercises: PreparationDocument2 pagesWriting Skills Practice: An Invitation - Exercises: Preparationساجده لرب العالمينPas encore d'évaluation

- Sacred Heart Seminary Alumni Association 2021Document4 pagesSacred Heart Seminary Alumni Association 2021Deo de los ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Vs MultinationalDocument7 pagesGlobal Vs MultinationalAhsan JavedPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter-2 The Oromo of EthiopiaDocument46 pagesChapter-2 The Oromo of Ethiopiaልጅ እያሱPas encore d'évaluation

- Rubric and Short Story Assignment ExpectationsDocument2 pagesRubric and Short Story Assignment Expectationsapi-266303434100% (1)

- Secularism in IndiaDocument13 pagesSecularism in IndiaAdi 10eoPas encore d'évaluation

- Madhukar 1Document2 pagesMadhukar 1Ajay SharmaPas encore d'évaluation