Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Death in Motion: Funeral Processions in Roman Forum

Transféré par

wfshamsTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Death in Motion: Funeral Processions in Roman Forum

Transféré par

wfshamsDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Death in Motion

Funeral Processions in the Roman Forum

d i a n e fav r o

University of California, Los Angeles

christopher johanson

University of California, Los Angeles

T

he calendars of republican and imperial Rome were represent spatial and urban relationships.5 The examples,

overflowing with a plethora of religious and state one from the mid-Republic and two from the imperial pe-

events, many of which were marked by animated riod, demonstrate changes in the interplay between Roman

parades that wound through the city. Interspersed among funerary practices and a specific urban space and provide a

these were melancholy processions that carried the deceased platform for the use of phenomenological analysis. This re-

from home to a final resting place outside the walls of the search lays the groundwork for a comparison of the use and

capital. For members of the elite, the route and activities of manipulation of architecture and imagery in the Republic

the Roman funeral offered a valuable opportunity to display and Empire.

and increase their symbolic importance.1 Previous studies The experiential aspects of any event in the forum re-

have considered the long history of funerals in antiquity, quire an understanding of that entire space as well as of those

commemorative activities such as the burning of the pyre parts of the surrounding cityscape that are connected visually

outside the city limits, or specific features such as the carry- and aurally to the forum. With only fragmentary physical

ing of death masks.2 Few have contextualized the funerary remains, the forum has rarely been reconstructed in toto as

procession ( pompa funebris) with specific spaces or in relation it existed in any specific period, although there are general-

to the intricately constructed Roman experience of a funeral.3 ized reconstructions representing entire eras (e.g., the repub-

Rome’s most illustrious and ambitious citizens choreo- lican forum) and simplified representations devoid of texture,

graphed their funerals with memorable activities in the color, artwork, people, and other rich sensory-stimulating

Forum Romanum, yet the effect of this symbol-laden public features.6 The late imperial forum has most frequently been

venue on the honorific imperial funeral parades and activities reconstructed because the archaeological remains from this

has not been critically evaluated.4 era are the best preserved.

Three funeral parades will be analyzed and illustrated In general, scholars have avoided making either pictorial

contextually using interactive, immersive digital models of or three-dimensional physical reconstructions of the forum

the Forum Romanum that have been specifically designed to as an urban space, for obvious reasons. The scientific recre-

ation of larger scale environments is extremely time consum-

Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 69, no. 1 (March 2010), 12–37. ISSN ing, requiring extensive research, which detracts from a

0037-9808, electronic ISSN 2150-5926. © 2010 by the Society of Architectural Historians. scholar’s focus on particular issues.7 In addition, there are dis-

All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for permission to photocopy or reproduce

article content through the University of California Press’s Rights and Permissions web-

ciplinary deterrents. The fashioning of an entire urban space

site, http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintInfo.asp. DOI: 10.1525/jsah.2010.69.1.12. requires hypotheses and assumptions about many unknown

JSAH6901_03.indd 12 2/2/10 5:19 PM

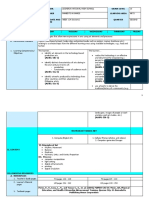

Figure 1 Late republican or early imperial relief depicting a funerary procession from Amiternum, Italy. Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo, L’Aquila (photo

by Christopher Johanson)

aspects, including the upper floors of buildings, the place- Romans constructed complex mental pictures of this site,

ment and scale of art, colors, textures, and ephemera (such as which were informed by references in texts, depictions of

plantings, scaffolding, and banners). Too often reconstruction individual buildings, word of mouth, and actual visits.12

images or models do not make variations in level of accuracy Given this collective familiarity, it is not surprising that the

visible. Such indeterminacy, no matter how well reasoned, is forum was rarely represented holistically in Roman art.

unpalatable to many scholars, but especially to archaeologists, Two notable exceptions are the marble imperial reliefs

who are trained to appreciate accuracy, not speculation.8 known as the Anaglypha or Plutei Traiani/Hadriani, which

The close experiential reading of historic processions were found in the forum in 1872.13 Although their exact

such as the Roman funeral has also been hampered by the placement and date are disputed, scholars agree that the

scarcity of specific details of these events. Only a few impe- scenes represent events occurring in the forum. On one an

rial funerals are described at length by ancient authors; even emperor (either Trajan or Hadrian) stands on the Rostra Au-

fewer by contemporary eyewitnesses. Furthermore, these gusti (speaker’s platform) while giving a public address or

accounts by male elite voices generally serve specific agen- adlocutio backed by six lictors (Figure 2); on the other an em-

das and often use the description of a funeral for calculated peror seated on the opposing rostra oversees the burning of

effect.9 Few detail the setting of the funeral or mention the debt books (Anaglypha) (Figure 3).14 Behind the figures rise

sensorial impact of the sights, sounds, and smells of the the Basilica Iulia and other buildings on the southwest side

emotionally and politically charged event, perhaps because of the forum. Although the reliefs may not have been seen

they considered such perceptual information too obvious to together in their original disposition, they show a continuous

merit comment. The same familiarity may explain the rela- architectural setting. The myth-laden fig tree (Ficus Rumi-

tive silence about funeral activities.10 Depictions of ancient nalis) and the statue of Marsyas appear in both reliefs, affirm-

processions in art tend to focus on the participants and offer ing the coincidence of the setting; one depicts the area east

only limited representation of the physical context, which of the statue and the other, the west.

would inform an assessment of the experiential impact. Gra- The overall representation is quite revealing about the

ham Zanker has perceptively noted that the omission of Romans’ experience of public events in the forum. The carv-

architectural environments in ancient art provoked viewers ings selectively mix accurately represented features (such as

to complete the picture in their minds, an act of supplemen- the blank segments that correspond to the streets that entered

tation that engaged ancient observers, but frustrates modern the forum) with inaccurate building orientations.15 All of the

historians (Figure 1).11 structures are seen frontally, regardless of their actual posi-

The situation is exacerbated for the Forum Romanum. tioning. For example, in the Debt Burning relief, the Temples

The geographical touchstone of the Roman world, this of Saturn, and of Divine Vespasian are shown side by side,

urban space was well known; throughout the vast empire, though they actually stood at right angles (see Figure 3). Such

D e at h i n M o t i o n : F u n e r a l P r o c e s s i o n s i n t h e R o m a n F o r u m 13

JSAH6901_03.indd 13 2/2/10 5:19 PM

Figure 2 Adlocutio relief of the Anaglypha (Plutei Traiani), showing events in the imperial Forum Romanum with the buildings on the southwest side as

backdrop; late 2nd century. Currently located in the Curia of the Forum Romanum, Rome (photo by Diane Favro). See JSAH online for high-resolution,

zoomable image with buildings of the Forum identified

Figure 3 Debt Burning relief, from the same monument as the Adlocutio relief, showing action in front of the opposing Rostra just visible in the

lower right corner. Currently located in the Curia building of the Forum Romanum, Rome (photo by Diane Favro). See JSAH online for high resolution,

zoomable image with buildings of the Forum identified

an unrealistic arrangement was not solely a result of the up to him both literally and metaphorically (see Figure 2).

pragmatic restrictions of the relief format, but owed also Action occurs below and leads the eye toward the emperor

to Roman experiential interpretations that were filtered either by the directional movement of the figures or the turn

through cultural ideas of viewing and processing.16 of their heads. In the Debt Burning relief, soldiers carry the

Ancient texts and pictorial representations affirm that the heavy account books toward the seated emperor atop the

Romans believed buildings of importance should be viewed Rostra Augusti. The fire consuming the records is appropri-

frontally, ideally from an inferior position.17 Vitruvius spe- ately set before the Temple of Saturn, site of the state treasury,

cifically recommended that temples along “the sides of public and at the feet of the seated emperor on the rostra. In reality,

roads should be arranged so that the passers-by can have a Saturn’s temple stood farther west, at a higher elevation and

view of them and make their reverence in full view.”18 Such behind the speaker’s platform. In the Adlocutio relief the men

hierarchical positioning was regularly employed to indicate forming the crowd lean slightly forward toward the emperor,

the status of depicted individuals. In the Adlocutio relief, the their garments clearly identifying status: the toga for senators

emperor is elevated atop a speaker’s platform; all figures look toward the front of the crowd, the paenula for poor citizens

14 j s a h / 6 9 : 1 , m a r c h 2 010

JSAH6901_03.indd 14 2/2/10 5:19 PM

pushed to the rear (see Figure 2). Gestures clarify the action,

with the standing emperor raising his arm in a familiar signal

of address. Overall, the emphasized body language under-

scores the importance of visual cues in an open space where a

speaker’s words quickly wafted away.19

The reliefs also demonstrate the active role of statues

whose location in the visual hierarchy is equal (or superior)

to that of the human participants in forum events.20 In this

case the artist selected, from among all the statues in the

forum, a depiction of Marsyas, which was associated with

libertas, and a group with Italia, her children, and the seated

Trajan, which celebrated the alimentary program. The reliefs

reinforce the closed topographical experience of the imperial

Forum Romanum, which afforded limited views of the sur-

rounding city, focusing inward on the two opposing rostra

that defined the space and action.

Despite their usefulness in explicating the interaction

between public events and the forum, the Plutei Traiani leave

many questions about the experience of the events unan-

swered. How did accompanying sounds reinforce the activi- Figure 4 Diagram of triumphal route from Campus Martius, moving

ties? Did lighting and temperature affect the participants’ counterclockwise around the Palatine, through the forum, and up to

comfort? Was color used to attract the eye? Did the smell of the Capitoline (image by Diane Favro)

the burning books drive the audience away? Where did spec-

tators stand? Were women and slaves allowed to watch? models have for decades been the primary instruments for

What route to the forum was taken by participants? making reconstructions of historic environments, yet these

Unfortunately, the established methodological appara- can be costly and require skills not developed by scholars.

tus for analyzing the symbiotic exchange between kinetic Furthermore, the necessity to present scholarship in text-

ceremonies and urban form is not especially useful for an- based publications has favored simplified, static visual repre-

cient specialists. Modern anthropological and urban analyses sentations, which are in many ways antithetical to the

are usually based on first-person documentation, interviews, experience of events such as ritual processions. In the formu-

and cognitive mapping; such approaches are not applicable lation of research, as well as its publication, lively parades with

to periods when voices are few and primarily of the elite. fluttering banners, cacophonous sounds, and animated danc-

Techniques developed to convey kinetic progression, such as ers are distilled into static lines on two-dimensional plans

the serial views and cognitive maps popular with urban plan- (Figure 4).26 Such depictions disguise the realities of topogra-

ners in the 1960s, have rarely been included in the architec- phy, three-dimensional sequencing, temporal changes, and

tural historian’s toolbox.21 the ease (or difficulty) of movement, among other factors,

During subsequent decades, the popularity of reception while emphasizing particular aspects (sequencing), experi-

theory led to increased interest in the “gaze.” In Roman stud- ences (static viewing), and approaches (semiotics). Verbal or

ies, a number of publications dealt with viewing in situ. Most cinematic attempts to recreate the experience of moving

considered intervisuality in elite artworks and environments, through a historic city can be evocative, but are often devalued

usually the Roman house.22 A few employed semiotic ideas by the scholarly community as too fanciful or entertaining.

to consider the experiences of urban buildings as linked to- Today researchers interested in the experiential aspects

gether to form narratives.23 While some authors explored of the ancient funeral—its sights, movement, sounds, and

kinetic viewing, the majority emphasized what could be seen smells—have more data, improved tools, and advanced

from fixed positions, a preference that minimized the impact methods with which to work. New technologies and ap-

of peripheral viewing and the full-bodied, synergistic inter- proaches to “knowledge representation,” a term borrowed

play of all the senses.24 Beyond sight, sensorial analyses of from the sciences, facilitate the reconsideration of historic

Roman environments have been few.25 events that were situated within sensorially rich, kinetically

In part, the available representational tools have been experienced environments. Digital recreations visually and

deterministic. Sketches, measured drawings, and physical experientially aggregate current knowledge about the

D e at h i n M o t i o n : F u n e r a l P r o c e s s i o n s i n t h e R o m a n F o r u m 15

JSAH6901_03.indd 15 2/2/10 5:19 PM

Figure 5 Diagram of extended funeral

routes at Rome in 160 BCE (image by

Christopher Johanson)

environment. Digital technologies have made possible the specifics about the route are few.30 There is no description

fashioning of more dynamic and flexible depictions of ancient of the parade path before it arrived in the forum, and the

spaces for use in research, teaching, and presentation, all purpose of the procession can only be speculated. It would

readily linked to metadata that documents the level of accu- seem that it functioned both as a means of gathering the

racy of restored components.27 Scholars can now reconstruct participants, who would later crowd the forum during the

historic environments that allow observers to move in real funeral oration, and as a way of displaying the popularity

time through carefully constructed topographic contexts. A of the deceased and the family.31 Hence, the more circu-

rich range of sensorial stimuli can be added to kinetic viewing itous the route, the better the attendance for the event, an

to shape more robust recreations of the original environmen- important factor at least during the Republic when funer-

tal experience. Depictions of actual times of day, year, and als had to vie for attention from citizens who continued to

century reaffirm the essential temporal aspects—the fourth conduct their daily business in the forum.32 The reality of

dimension. Various experimental scenarios can be presented housing distribution in Rome further complicated mat-

to ascertain the impact of alternative reconstructions, climatic ters. The aristocracy lived along the streets that led into

conditions, and hypothetically distributed ephemera.28 the forum (including the Sacra Via) and on the nearby

Every sensorial layer requires a method of citation and Palatine Hill. 33 Therefore, most aristocratic funerals

analysis, and a large measure of scholarly caution. How can began only a few hundred meters away from the forum

it be proved that ancients experienced light in the same way itself. In order to lengthen the parade route and attract a

as moderns? How does one add scholarly rigor to the simula- larger audience, processions from residences near the

tion of smell or sound? Various sensorial additions to a sim- forum may have diverted to side streets to extend the route

ulation can detract if they are included as an afterthought, to the forum (Figure 5).34

even if an illustrative one. Parades most likely entered along the Sacra Via in the

Roman environments have been among the first to be mid-republican period, a symbolically potent route followed

extensively recreated digitally. The attraction reflects aware- in numerous ritual processions, including the triumphal pa-

ness of the experiential richness of Roman design. Not sur- rade, which was an event that the funeral procession mim-

prisingly extensively designed rooms, such as those preserved icked in many ways.35 Upon entering the forum, the pompa

at Pompeii, are cited as early immersive “simulations.”29 funebris crossed the central open plaza to the rostra, where

Given the ancient evidence and the current technological the deceased was put on display (Figure 6).36 From atop the

toolset, Roman spatiality offers the greatest opportunity for rostra the primary heir gave a eulogy, flanked by members of

serious scholarly investigation. the cortege who wore ancestor masks (imagines) and sat in a

row of ivory chairs that faced the assembled crowd. Scholars

have underlined the obvious potential for symbolic manipu-

The Mid-Republican Funeral Procession lation in the content of the speech (laudatio funebris), the

(183 BCE–145 BCE) ancestor masks, and the composition of the crowd.37 Less

Ancient accounts of funerals during the mid-Republic de- analyzed, but equally significant, are the sights, kinetic

scribe the movement of the aristocratic pompa funebris sequences, and interaction with the physical environment

through the city to the Forum Romanum. Unfortunately, experienced by the funeral parade.

16 j s a h / 6 9 : 1 , m a r c h 2 010

JSAH6901_03.indd 16 2/2/10 5:19 PM

Figure 6 Schematic representation of the funeral eulogy (image © and Figure 7 Schematic representations overlaid on a geographic coordi-

courtesy of the Regents of the University of California, Christopher nate system (image © and courtesy of the Regents of the University

Johanson, and the Experiential Technologies Center [ETC]) of California, Christopher Johanson, and the Experiential Technologies

Center [ETC], UCLA)

Physical and textual evidence demonstrate that the conditions. The current paving in the modern archaeological

forum during the mid-republican period was radically differ- park lies 2 to 4 meters above the republican forum floor.

ent in appearance than its imperial descendants.38 Sadly, Major buildings from the mid-Republic period are repre-

there is a severe lack of robust archaeological data about the sented by scattered fragments often immured or obliterated

buildings in the forum during the first half of the second by subsequent rebuildings.43 The republican remains of the

century BCE. In situ evidence for the third (vertical) dimen- great temple to Jupiter atop the Capitoline are today encased

sion is particularly difficult to find. Today’s researchers can within the Palazzo dei Conservatori, its visual connection to

bring into play additional information, including high-reso- the forum blocked by post-antique construction.

lution satellite imagery, citywide cadastral maps, and GPS Experiential understanding has been further compro-

coordinates that precisely situate verifiable archaeological mised by the inaccurate siting of buildings on published

remains within a geographic coordinate system, yet they still plans. For example, no readily available plans use a unifying

lack sufficient data to create academically justifiable hyper- geographic coordinate system to demonstrate and validate

realistic reconstructions.39 the precise location of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maxi-

In most cases, only the general massing of buildings and mus in relation to the buildings of the mid-republican forum.

architectural monuments can be modeled with any certainty. Three-dimensional paper-based reconstructions, hampered

For this research the models are schematic, shaded for legibil- by modern in situ viewshed difficulties, only approximate the

ity, but necessarily textureless.40 They are knowledge repre- original visual relationship between Capitoline and forum;

sentations of the current evidence—more often textual than furthermore the majority of reconstructions depict the state

material—and can approximate only one of many interpreta- of the forum in the imperial period and adopt an omniscient

tions of the mid-republican forum’s appearance.41 Strict care god’s-eye view.44 The most accurate three-dimensional re-

must be taken to map out the parameters for each exploration constructions represent the area during either its Augustan

and to explain its experimental nature (Figure 7).42 Within or late imperial phases, and even these frequently exaggerate

these working parameters, however, valuable investigations the elevation information to such an extent that perceptions

can be undertaken about the experiential and propagandistic have been powerfully informed by the image of Jupiter’s

impact of the funeral on the processors and audience mem- temple looming majestically over the city (Figure 8).45

bers, and in particular the importance of the critical intervis-

ibility between buildings in and near the Forum Romanum.

The multilayered visual effects of the parade route re- Case Study 1: The Funerals of the Cornelii

quire three-dimensional analysis, but an in situ examination The funerals of the mid-Republic (183–145 BCE) provide

of the viewshed and relationship between the Capitoline Hill a useful case study of republican funerary practices.46 The

and the republican forum is impossible due to present-day Cornelii were a prominent aristocratic family of the middle

D e at h i n M o t i o n : F u n e r a l P r o c e s s i o n s i n t h e R o m a n F o r u m 17

JSAH6901_03.indd 17 2/2/10 5:19 PM

Figure 8 Reconstructed drawing of Roman Forum and Capitoline Hill showing the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill, after

Alberto Carpiceci in Rome 2000 Years Ago (Florence: Bonechi, 1981), 8–9. See JSAH online to compare the elevation of the temple in this hypotheti-

cal reconstruction to that of the same temple in the more accurate digital reconstruction

republic, and the only clear evidence of the occasional altera- appropriately large crowd (see Figure 5, Figure 9).52 The de-

tion of the usual processional route is associated with this tour to the Capitoline Hill to acquire the important ancestral

clan.47 To the traditional cortege path, which moved from the mask significantly lengthened the parade. Simultaneously, it

house of the deceased to the rostra in the forum and then to emphasized a sequence of vistas to notable buildings, art, and

the burial site, the Cornelii added a visit to the Capitoline Hill urban features that were seen by parade participants and a

to collect the wax mask (imago) of Scipio Africanus, the famed reciprocal sequence of views of the funeral parade by the au-

conqueror of Hannibal during the second Punic Wars and the dience gathered in the forum. Although it is problematic to

most illustrious member of their family. They introduced this build an argument about the Roman funeral of the middle

new itinerary after Scipio’s death in 183 BCE.48 Republic based on a famous exception, a visual analysis of the

Roman aristocratic families usually housed such imagines

of ancestors who had attained a curule magistracy in dedicated

cupboards in the atria of their residences. Only on special oc-

casions were these open for viewing, and only at the Roman

funeral were the masks paraded through the streets.49 For rea-

sons not entirely clear, the wax mask of Scipio Africanus was

placed in the cella of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus,

in effect equating the residence of the most powerful god in

the Roman pantheon with the atrium of Scipio’s house.50

The Cornelii followed other practices that differed from

the norm. For instance, while the rest of Rome cremated their

loved ones, the Cornelii continued to inhume the deceased.51

Figure 9 Schematic reconstruction of the Roman Forum (183 BCE).

Perhaps the reason was pragmatic; the house of Scipio Afri-

The House of Africanus may have been located adjacent to the Temple

canus stood immediately next to the Roman forum behind the

of Castor on the south side of the central plaza (image © and courtesy

Tabernae Veteres, which meant that a funeral procession to

of the Regents of the University of California, Christopher Johanson,

the republican rostra (located directly to the northeast of the and the Experiential Technologies Center [ETC], UCLA). See JSAH

later Rostra Augusti) would have been a short walk of less online for an analogous view of the republican Roman Forum keyed to

than one hundred meters—not long enough to attract an a real-time, three-dimensional model set in its geographic context

18 j s a h / 6 9 : 1 , m a r c h 2 010

JSAH6901_03.indd 18 2/2/10 5:19 PM

alteration of the Cornelii’s processional route offers a poten- The two reconstructions give notably different results

tial key to understanding the choreography of this mid-sec- when viewed virtually from the mid-second century BCE

ond-century event. The case study places the evidence for the forum as reconstructed. With Gjerstad’s version, whose

funeral into the reconstructed topographic context of 183– dominating form is seen in most reconstructions, the temple

145 BCE (Figure 10). pediment looms over the city, clearly visible to spectators

After the imago of Scipio Africanus was placed in the standing at ground level in the eastern end of the forum (Fig-

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, funeral processions for ure 10d). From elsewhere in the forum, observers would have

the Cornelii clan began at the house of the deceased family seen the entablature and roof of the temple, but caught only

member, moved through the forum, and then turned away glimpses of its podium (Figure 10e). The fortunate ones who

from the gathering crowd to ascend the Clivus Capitolinus had staked out desirable positions near the rostra were well

(Figure 10a).53 Once the cortege moved past the Temple of situated to see the bier and the actors wearing ancestor masks

Saturn, visual contact with spectators in the low-lying forum line up in front (see Figure 7). They could readily hear the

plaza was severed. How the imago was collected from the eulogies and see other activities associated with the funeral,

temple has not been recorded, but presumably the event oc- but except for those positioned directly in front of the rostra,

curred atop the Capitoline Hill before the south-facing the view to the façade and area in front of Jupiter’s distant

Temple of Jupiter, where an actor wearing triumphal regalia temple was almost entirely occluded.

donned the mask (Figure 10b). The action would have been Stamper’s reconstruction reduces the temple’s overall

visible from the aristocratic houses on the northwestern size and profile, eliminating nearly all views of it from the

Palatine for those with an unobstructed view and good eye- ground level of the forum (Figure 10f ). Viewsheds from

sight, yet most of the nobility would have already joined the more elevated positions would not have been much better.

awaiting audience in the low-lying forum.54 Some curious Observers who jockeyed successfully for viewing spots in the

spectators may have followed the musicians, mimes, and upper balconies (maeniana) above the shops in front of the

dancers as they proceeded up the hill to the Capitoline tem- Basilica Sempronia on the west side of the forum had good

ple, but the Clivus Capitolinus, and even the much larger views of the rostra and the central open space, but not of the

platform on the hill above, offered only limited room to turn Capitoline (Figure 10g). Only those on the upper level of the

a large procession. Doubtless, most spectators preferred to shops fronting the Basilica Fulvia across the open space could

secure good viewing spots for the oration in the forum. How readily see the Temple of Jupiter and, at a lower level, the

did the Cornelii connect this unique segment of their family Cornelii funeral parade as it re-entered the forum (Figure

funeral with the more traditional program of the republican 10h). Furthermore, in a culture where seeing and being seen

funeral? To what degree were the symbolic connections be- were both important, most of these spectators would not

tween the funerary activities at the rostra and those on the have been visible to those clustering around the rostra.57 Cu-

Capitoline magnified by spectacle? riously enough, in the two reconstructions only the Comi-

Digital reconstructions facilitate the experiential ex- tium, the natural cavea to the northwest of the rostra, affords

amination of the connections between the forum and the clear views of the Temple of Jupiter (Figure 10i).

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in this period (Figure Clearly, an understanding of the Roman funeral neces-

10c).55 Unfortunately, without information on sounds, sitates knowledge of the context of the event. Just as there are

smells, and haptic responses, the exploration remains vision- alternative reconstructions of the built environment, there

centered, an emphasis that must be constantly kept in mind. are likewise alternative reconstructions of the performance,

Static and kinetic viewsheds are predicated on the accurate including most importantly, the orientation of the primary

depiction of an environment and of building massing in par- speakers. One interpretation is based on the later funerary

ticular. In this instance, the height and footprint of the customs of Ciceronian Rome in the late first century BCE;

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus remain somewhat con- the other is shaped by an appreciation of the oratorical prac-

troversial. The dispute centers on whether the measure- tices of the mid-Republic over a century earlier. An assess-

ments given by Dionysius of Halicarnassus and confirmed ment of the visual impact of the funeral parade of the Cornelii

by recent archaeological work can refer to the temple’s po- clarifies the differences between these two scenarios.

dium, as asserted by Einar Gjerstad in the 1960s—a recon-

struction that produces intercolumniations substantially Alternative 1: Orators Face the People

larger than even those of the Pantheon—or to a platform on Since their view was blocked by many of the surrounding

which a smaller structure rose, as championed more recently buildings (Figure 11), the audience gathered in the forum

by John Stamper.56 would have gauged the approach of the Cornelii funeral

D e at h i n M o t i o n : F u n e r a l P r o c e s s i o n s i n t h e R o m a n F o r u m 19

JSAH6901_03.indd 19 2/2/10 5:19 PM

10a 10b 10c

10d 10e 10f

10g 10h 10i

Figure 10 The Forum in 160 BCE, with views 10a–i marked on the map (image by Christopher Johanson; 10a–i © and courtesy of the Regents of the

University of California, Christopher Johanson, and the Experiential Technologies Center [ETC], UCLA). See JSAH online for a bird’s-eye view of a

real-time, three-dimensional model of the republican Roman Forum (160 BCE) set in its geographic context. 10a Elevated view from the northeast

corner of the Forum looking toward the Capitoline Hill; 10b Bird’s-eye view of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. The northwest corner of the

Roman Forum is visible on the right; 10c View of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (based on Gjerstad) from the north side of the Forum plaza;

10d Partly occluded view of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (based on Gjerstad) from the southern side of the Forum plaza; 10e View of the

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (based on Gjerstad) from the area in front of the Rostra; 10f Occluded view of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus

Maximus (based on Stamper) from the Lacus Curtius; 10g Panoramic view of the occluded Capitoline Hill (left) and the Comitium (right) from the bal-

cony of the Basilica Sempronia; 10h View from the balcony of the Basilica Aemilia of the Rostra with the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (based

on Gjerstad) clearly visible in the background; 10i View of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus from the steps of the Curia Hostilia

20 j s a h / 6 9 : 1 , m a r c h 2 010

JSAH6901_03.indd 20 2/2/10 5:20 PM

11a 11b 11c

11d 11e 11f

11g 11h

Figure 11 Schematic view of the Forum with views labeled (image by Christopher Johanson; 11a–h © and courtesy of the Regents of the University

of California, Christopher Johanson, and the Experiential Technologies Center [ETC], UCLA). See JSAH online for a bird’s-eye view of a real-time, three-

dimensional model of the republican Roman Forum set in its geographic context. 11a View from the area in front of the Rostra, populated by hypothet-

ical bystanders, looking toward the Temple of Saturn and the Clivus Capitolinus, the main road leading down from the Capitoline Hill; 11b View of the

orator, bier and ancestors atop the Rostra; 11c Elevated view from the balcony in front of the Basilica Sempronia; 11d View of the Basilica Porcia (to

the left of the Curia Hostilia). The Basilica is represented in schematic form omitting the colonnaded lower and upper levels; 11e Privileged view of

the Rostra from the northern side of the Comitium; 11f Bird’s eye view of the Forum illustrating the intimacy of the Comitium in comparison to the

open Forum plaza; 11g View from the Comitium of the imago of Scipio Africanus as it returns from the Capitoline Hill; 11h View from the Comitium

of the imago of Cato entering or leaving the Curia Hostilia. See JSAH online for an analogous view keyed to a real-time, three-dimensional model

set in its geographic context

D e at h i n M o t i o n : F u n e r a l P r o c e s s i o n s i n t h e R o m a n F o r u m 21

JSAH6901_03.indd 21 2/2/10 5:20 PM

procession down from the Capitoline by the smoke rising mid-second century, orators faced the Comitium and the

from torches and the sounds (Figure 11a). The accompanying Curia, not the forum.64 The implications of this original, re-

music and chants became gradually louder, reaching a cre- versed staging have not been fully explored. Was the funerary

scendo as the cortege laudatio originally configured in the same way?

rounded the Temple of The topography of the area facilitates a reconstruction

See JSAH online Saturn at the lower ter- with a Curia-centered oration. Until at least 184 BCE the

for a re-creation of Roman minus of the Clivus Cap- Cloaca Maxima, which ran through the middle of the forum,

funeral music and ritual itolinus and burst into was apparently uncovered.65 It would have formed a natural

lamentation based on full view of the awaiting partition between the large eastern portion of the forum’s

experimental archaeology. crowd.58 At this potent central plaza and the western half, occupied by the political

moment the sound level nucleus of the Curia, the Comitium, the senaculum, and the

escalated, freed from the constraints of the narrow, building- Graecostasis.66 The natural topography of the area formed a

lined street. (Of course, wind, weather, and ambient noise theatrical cavea centered on the rostra. The Comitium lies in

would have diminished this aural effect.) The elevated imago a small depression surrounded by gentle upward slopes on all

of Scipio Africanus was prominent, along with the ancestor sides save the forum plaza.67 The Temple of Saturn offered a

masks of the deceased and other illustrious Cornelii. The pro- lengthy stepped approach that would have served as a con-

cession stopped at the northwest corner of the forum and venient tiered viewing area. M. Porcius Cato’s decision as

mounted the rostra where the body of the departed was dis- censor to buy up land near the Curia to build the first named

played (Figure 11b). The jostling audience at ground level basilica in Rome (the Basilica Porcia) implies that this was a

looked up to the famous ancestors represented by actors wear- space that, among other things, would benefit from a public

ing death masks who were seated among the statues crowding porticoed structure, that is, a shaded viewing area (Figure

the platform; behind them the Curia Hostilia formed a monu- 11d).68 The masses would have gathered in the forum plaza

mental backdrop.59 The ancestors, in turn, looked down on and at the southwest end of the forum in front of the Temple

the majority of the audience—the inverse of the spatial ar- of Saturn, but the elite would fill the Comitium, line its steps,

rangement in Greek oratory. Only the spectators on the upper and command the privileged views next to the seat of magis-

floors of the basilicas could look down on the speakers, but terial power, the Senate House (Figure 11e). The speaker

their viewing status from a position on high was diminished would be elevated above many of the people, but the elite

by a lack of visual clarity due to distance (Figure 11c).60 could demonstrate their own station by being in clear sight

As appropriate for Roman viewing conventions, the fu- of the speaker and by forming the backdrop seen by the sur-

neral participants on the rostra saw senators and other elite rounding audience.

citizens positioned close by, identifiable by their garb and If political oratory required the speaker to face the

placement, an important factor since no clear physical Curia, one must contemplate the practical ramifications of

boundary separated them from the masses on the forum this substantially different staging. While the famous beaks

floor. The son of the deceased, if there was one of suitable of the rostra pointed toward the forum, in which direction

age, faced the forum and the crowd to give the laudatio and did the statues face? Imperial reliefs always depict the speaker

then praised, in chronological order, the ancestors arrayed and the statues facing the same way. It seems unlikely that the

behind him.61 After the speech the group descended from the majority of political oratory in the mid-Republic would be

rostra and, amid mourning wails, carried the deceased to his framed by the backs of those commemorated in stone. 69

final resting place outside the city.62 Funerary games (ludi What of the audience? A Curia-centered oration would have

funebres and munera), most likely held in the forum followed, taken place in a relatively intimate setting. Because of the

completed the ceremony. naturally sloped and stepped viewing area, the audience

could both see and be seen more effectively. Many would be

Alternative 2: Orators Face the Senate close enough to hear the speech clearly. Moreover, assem-

As recognized by modern scholars, the rostra became the ora- bling in the western end of the forum would mitigate the

torical stage for the forum in the late Republic. Only in 145 interference caused by the open shops and the ongoing busi-

BCE did the orientation reverse when a tribune first turned ness surrounding the forum plaza (Figure 11f ). Of course,

his back on the Curia to address the people directly, a populist for those farther removed from the rostra and who could not

move meant both to appease the masses and annoy the mag- hear, gestures would still convey the meaning, although it

isterial classes.63 Thus the interpretation given in Alternative would require a skilled orator to use gestures that even an

1 is based on a retrojection from a later period. Prior to the audience facing his back could interpret.

22 j s a h / 6 9 : 1 , m a r c h 2 010

JSAH6901_03.indd 22 2/2/10 5:20 PM

The grouping of the spectators on the western side of the The parade route from Jupiter’s temple to the forum sug-

forum also alters the potential symbolic viewsheds, for in this gested a direct connection between Scipio Africanus, his

location the speaker and the audience can share the same de- descendants, and the great god by highlighting a genetic and

ictic references to the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.70 a spectacular topographic descent.72

As the procession of the Cornelii began to fill the Comitium The visual connection with the Temple of Jupiter was

and the surrounding space, a branch of the parade moved up desirable, but not essential. As the most important shrine in

the slope of the Clivus Capitolinus, in clear view of the major- the Roman world, its appearance was familiar to all specta-

ity of the more privileged spectators, those in the cavea to the tors. They did not have to see the connection; the wisps of

west of the Comitium (Figure 11g). Such attendees were smoke, the echoes of processional music, and the entrance of

situated well for the upcoming laudatio and could also view the cortege from the direction of the temple were enough to

the ceremony that was occurring on top of the Capitoline, in forge the associations desired by the Cornelii. It is clear,

either the Gjerstad or Stamper reconstruction of the Temple however, that in one possible configuration most of the audi-

of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. Even many of those outside the ence could have seen the event on the hill, and that an un-

Comitium would be able to witness the spectacle above. The derstanding of the visual impact of the Cornelii’s procession

value placed on such intervisuality explains why the Cornellii’s helps to clarify the organization of the event below. The

revered ancestor Scipio Africanus was transported in such a oratorical stage of the mid-Republic prior to 145 BCE was

way that he emerged from around the corner of the Temple different than that of the first century, and the earlier con-

of Saturn, thus clarifying the symbolic association. Even the figuration both better accommodates the evidence and better

uneducated (and the non-Latin speakers) would immediately solves practical logistical problems.

understand that this relative of the Cornelii’s clan had been

communing with the most powerful god in the city. Perhaps The Imperial Funeral and the Roman Forum

it was in emulation of the Cornelii’s bold symbolic association In the imperial era, power was focused in the hands of single

with the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus that the family individuals, but republican traditions and governmental

of the novus homo, Marcus Porcius Cato, installed his imago in structures continued, at least superficially.73 Beginning with

the Curia Hostilia, whence it was retrieved during funerary the commemorations of Augustus, funerals for the emperors

events.71 This familial competition would have been not only became iconic, with grand events in the forum. The choreog-

symbolic, but spectacular. Rather than remain hidden from raphy still included a parade and eulogies from the rostra, but

the audience by the rostra, the imago of Cato would have the ancestors who marched were largely stand-ins, not a col-

emerged from the Curia in full view of the parting crowd and lection of genetically related ancestors, but an assembly of

would have served as a reminder of this particularly admirable famous persons from Rome’s history. The body of the de-

ancestor (Figure 11h). ceased, too, was often represented symbolically rather than

Ancient sources note the exceptional funeral choreog- actually included. The speeches, like the event in general,

raphy of the Cornelii. Having two parades enter the forum addressed a world audience, since the death marked a change

certainly drew attention to the event and helped differentiate in state leadership.74

this funeral from others—a necessary goal given the number Imperial funerals were characterized by their great size,

of distractions in the city of Rome. Experiential analysis fa- magnificence, and especially by the inclusion of participants

cilitates a consideration of the link forged between the Cap- and features from throughout the empire.75 At the rostra the

itoline and the forum by the procession. The effect of this emperor’s body (or its simulacrum) lay on display in a shrine-

visual connection, in turn, permits reevaluation of the textual like structure recalling the baldachins of Eastern Hellenistic

evidence and reconsideration of the configuration of the rulers. The pompa funebris began at the imperial residence on

event. By emphasizing movement from the forum up to the the Palatine, descended the Clivus Palatinus, then moved into

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the program recalled the forum. While no exhaustive description of an imperial

the triumphal parade, an association reinforced by the garb- funeral exists, accounts written around 200 CE provide a

ing of the actor who wore the mask of Scipio Africanus in number of visual details about the events in the Forum Ro-

triumphal regalia. Yet the directional change of the proces- manum. In 193 CE the emperor Septimius Severus organized

sion, coming down from the hill rather than moving up to a lavish funeral in honor of his predecessor Pertinax and him-

the temple, underscored another connection even more self was honored by an extravagant event at his death in 211

strongly. The famous conqueror of Hannibal was acknowl- CE. Cassius Dio gave an eyewitness account of the first;

edged by some Romans to be the son of Jupiter, and his fu- Herodian, who resided in Rome during this period, com-

neral mask was thus kept in the “residence” of his progenitor. mented on the funeral of Septimius and others of his day.76

D e at h i n M o t i o n : F u n e r a l P r o c e s s i o n s i n t h e R o m a n F o r u m 23

JSAH6901_03.indd 23 2/2/10 5:20 PM

In relation to funeral activities, the most significant

physical change to the forum was the alteration to the speak-

er’s platform. At the end of the first century BCE Julius Cae-

sar reworked the traditional locus of speechmaking and

assembly near the Senate House. He summarily eliminated

the republican rostra and began construction on a new speak-

er’s platform, the so-called Rostra Caesaris, shifted to the

west, directly on axis with the open space that was now more

clearly defined by his large new Basilica Julia on the south-

west.78 The new platform, enlarged and completed by Au-

gustus (designated by scholars the Rostra Augusti), was the

Figure 12 Digital reconstruction model of the Roman Forum in the late

locus for many memorable events of those tumultuous years,

imperial period. See JSAH online for an analogous view keyed to a real-

including the funerals of Caesar and Augustus whose impact

time, three-dimensional model set in its geographic context (images ©

and courtesy of the Regents of the University of California, the CVRLab,

reverberated throughout subsequent state funerals.79 Cae-

and the Experimental Technologies Center [ETC], UCLA) sar’s funeral also inspired a major addition to the forum. After

a riotous crowd burned the dictator’s body in the forum

While funerals grew steadily larger, the physical space rather than at the burial site outside the city limits, Augustus

of the performance shrank significantly after the mid-Repub- marked the spot with a magnificent new temple to the deified

lic period. More permanent buildings and over-scale monu- Caesar (Divus Iulius) directly opposite the rostra.80

ments crowded the Forum Romanum. The increased Documentation of imperial funerals is more complete

verticality of the surrounding buildings sealed off much of than for those of the mid-Republic. Much more is also

the forum from external visual influence. While views toward known about the physical layout of the entire Forum Roma-

the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus had been difficult num in the later period. Better preserved and more thor-

to gain during the mid-Republic, they were almost entirely oughly excavated, the archaeological evidence for the high

blocked by the middle of the Empire (Figure 12). The arter- Imperial period is far more extensive, and it is thus more

ies leading into the area were narrowed as the basilicas ex- easily reconstructed. At least partial remains of many build-

panded on each side and arches spanning entire streets ings survive in situ, which facilitates modern surveys and

operated as doorways into the forum. The surrounding substantially increases the fidelity of the reconstructed set-

urban fabric also changed. To the east, the expanding impe- ting. The funerals of Pertinax and Septimius Severus offer a

rial fora wiped out vast areas of housing. The large imperial chance to explore how the topography of the forum affected

palace system on the Palatine supplanted private aristocratic and guided funerary activities.

houses as the focus of power and the launching point for

major funerals. As a result the route of a pompa funebris for an Case Study 2: The Funeral of Pertinax

emperor became truncated. Well publicized, the deceased In 193 CE Septimius Severus became emperor following the

emperor, or rather, his imago, did not have to move through bloody and short reigns of four predecessors, the last of whom

the city to attract spectators from their houses (most of which was Pertinax. Hoping to signal an end to turmoil, he imme-

were now concentrated away from the city center). The diately affirmed his right to power by declaring his predeces-

crowds came to him in the forum. sor to be a god and accepting the name Pertinax as his own.81

By the middle of the second century, the forum had like- To celebrate further his restoration of liberty and peace, the

wise become more restricted in activities and meaning. Al- same year Severus held a lavish funeral honoring the previous

though significant objects from the Republic remained emperor. At the head of the cortege were carried statues of

visible, every building, sculpture, painting, space, and event the viri illustri, famous Romans of the past, confirming the

was now imprinted with calculated imperial messages. The continuity and stability of Rome; these themes were rein-

layout of the forum had also become more rigidly defined. forced later in the parade by more statues of other historic

The central forum was now smaller, its “walls,” higher. The figures who were admired for their great deeds or discoveries,

large, opposing Basilica Julia and Basilica Aemilia framed the and by representatives of the city’s various collegia (associa-

two long sides. The central area was unified by sparkling tions). Along with male choruses singing funeral hymns pro-

paving, mostly of white marble, although the clarity of the cessed subordinate officials, soldiers and bearers of heavy

spatial volume was obscured by numerous eye-catching com- bronze statues whose regional costumes identified them as

memoratives and statues.77 representations of Rome’s provinces—symbols of the power

24 j s a h / 6 9 : 1 , m a r c h 2 010

JSAH6901_03.indd 24 2/2/10 5:20 PM

13a 13b

Figure 13 The Roman Forum of 191/92 CE (image by Christopher Johanson; 13a–b © and courtesy of the Regents of the University of California,

the CVRLab, and the Experimental Technologies Center [ETC], UCLA). See JSAH online for a bird’s-eye view of a real-time, three-dimensional

model of the imperial Roman Forum (191/92 CE) set in its geographic context. 13a View from the northwestern corner of the Temple of Divus

Iulius looking toward the Rostra Augusti and Temple of Concord; 13b View looking up at the Rostra Augusti with the Temple of Concord and Tabu-

larium behind. In reality the Temple of Vespasian and Titus to the west had not yet been repaired after being damaged in the fire of 191/92 CE

and geographic extent of the Empire. Racehorses and a pano- A participant in these funerary ceremonies, Cassius Dio

ply of funeral gifts alluded to the elaborate games to follow. provided a detailed description. Septimius first moved across

The procession climaxed with a portable golden altar be- the forum to the speaker’s platform (Figure 13). Behind him

decked with ivory and precious stones. came Cassius Dio and other senators dressed in somber togas

Notably, the actual remains of the deceased were not in of mourning; their wives followed, having eschewed colorful

the funeral parade. Pertinax, who had died months earlier garments for respectful white.83 Elite male attendees took

and had been cremated, was represented by a wax effigy, seats in the open air near the Rostra Augusti, where they

dressed in triumphal regalia and placed on view in a small were visible to all; the women moved to less-exposed loca-

building with columns of gold and ivory erected atop a tem- tions out of the sun in the shadowy porticos of the flanking

porary stage in front of the rostra.82 To maintain the fiction basilicas.84 In solemn anticipation, the patrician audience

of a traditional funeral with a corpse, and to displace the awaited the procession. Hearing a muddled cacophony of

memory of Pertinax’s bloody beheading, a slave boy waved a sounds coming from the walled portion of the sacred road

fan of peacock feathers as if to keep flies away from the de- between the Basilica Aemilia and the Temple of Divus Iulius,

composing body. The new emperor, now called Lucius Sep- all looked to the southwest. As the funeral parade passed the

timius Severus Pertinax, not the deceased’s son, gave the podium of the temple the sounds distilled into the distinctive

funeral oration, confirming his role as heir. dirges sung by the funerary chorus that accompanied the

D e at h i n M o t i o n : F u n e r a l P r o c e s s i o n s i n t h e R o m a n F o r u m 25

JSAH6901_03.indd 25 2/2/10 5:20 PM

Figure 14 Oration relief from the Arch of Constantine depicting the Rostra Augusti with columns. Behind rise the Basilica Iulia and Arch of Tiberius

and Basilica Iulia on the left, and the Arch of Septimius Severus on the right

statues of viri illustres at the head of the pompa (see Figure in an aside by Cassius Dio about the eulogy by Septimius:

11b).85 From their elevated position, the sculpted representa- “We shouted our approval many times in the course of his

tives of Rome’s history carried aloft in the procession looked address, now praising and now lamenting Pertinax, but our

directly toward the Temple of Concord, symbol of harmony shouts were loudest when he concluded.”89 The forum pro-

among the classes, rising majestically behind the rostra (Fig- vided a familiar, history-laden background for the action.

ure 13a). As the procession extended into the sunlit open Once in power, Septimius Severus and his wife Julia

space, attention was drawn to the effigy of the deceased in his Domna began to imprint their identity on the Forum Roma-

purple robes ensconced in a glittering golden shrine clearly num.90 Among the sculpted monuments that they added was

visible above the heads of the seated senators. Behind this a large equestrian statue, the Equus Severi, which recalled

tableau rose the towering façade of the Tabularium.86 the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius whom Septimius

Once the parade had passed the influential spectators, also claimed as his father.91 In the southern forum they re-

Severus mounted the rostra and gave the laudatio with the paired various structures ravaged by an earlier fire in 191/192

statues on the platform behind him bearing silent witness and CE.92 Affirming her role as matrona and wife of the pontifex

the crowd shouting in approbation.87 The senators seated maximus, Julia Domna assumed responsibility for rebuilding

near the Rostra Augusti craned their necks upward, their field the Temple of Vesta.93 At the opposite end of the urban space

of vision filled by the gesticulating emperor, surrounding Septimius and his sons restored the Temple of Vespasian and

retinue, and statuary (Figure 13b). One can imagine that the added an inscription commemorating their work. Honorific

laudatio included gestures toward the Temple of Concord, columns placed on top of the rostra date to the Severan pe-

where Pertinax had first met the senate after being proclaimed riod as well (Figure 14).94

emperor, or to the Temple of Jupiter, where the father of the These interventions paled beside the addition of a mag-

gods would welcome the newest member of the Roman pan- nificent new arch. Significantly, this was the first large, com-

theon.88 At the end of the speeches the senators proceeded plete building added to the central area of the forum since

out of the forum toward the tomb. They marched ahead of the Temple of Divus Iulius over a century earlier.95 In 202

the bier amid beating of breasts and cries of lamentation, with CE Septimius celebrated the tenth anniversary of his reign

the emperor and the effigy of the deceased following. (decennalia) and returned from successful eastern campaigns

Septimius used the funeral of Pertinax to validate his against the Arabs, Parthians, and Adiabeneans. He declined

claim to the throne. Traditional and reverential in nature, the a triumph, but along with his sons was voted an arch by the

choreography reflected the continuation (or fossilization) of senate and people of Rome completed by 203 CE.96 The

the established model for funerals, which emphasized the em- massive monument still stands north of the Rostra Augusti,

peror as representative of the collective. In Pertinax’s funeral, near the Comitium, a spot chosen in part to affirm the locus

participants carried statues representing illustres viri from of a prescient dream of Septimius (Figure 15).97 The inscrip-

Rome’s history, not the illustrious ancestors of the deceased. tion honored the emperor as “Pertinax” and “son of Mar-

The staging reflected the realities of the imperial govern- cus” for having achieved “the restoration of the state and the

ment, assigning the senators to a more symbolic and passive extension of the empire.”98 Detailed reliefs recounting the

role than that played by their republican predecessors. They successful campaigns embellished the two facades, and an

sat as spectators awaiting the action and responded on cue impressive sculptural display of the emperor in a chariot

with moans and lamentations. A hint of their attitude is given flanked by his sons originally stood atop the monument

26 j s a h / 6 9 : 1 , m a r c h 2 010

JSAH6901_03.indd 26 2/2/10 5:20 PM

Figure 15 Reconstruction model of the Arch of Septimius Severus; Figure 16 Arch of Septimius Severus as it appears today (photograph

the surmounting bronze sculptures of the emperor and his sons are by Diane Favro). (See JSAH online for an analogous view keyed to a

not shown (image © and courtesy of the Regents of the University real-time, three-dimensional model set in its geographic context)

of California, the CVRLab, and the Experimental Technologies Center

[ETC], UCLA). See JSAH online for an analogous view keyed to a real-

time, three-dimensional model set in its geographic context

(Figure 16). The style and complex iconography of the garbed in white rang out from temporary bleachers on one

carvings and sculpture have been thoroughly explored.99 side of the “body,” those of children similarly dressed rose

The monument was obviously a counterpoint to the from bleachers from the other side.

arch located southwest of the rostra, which Tacitus described Such a generalized description only partially conveys

as propter aedem Saturni.100 That memorial celebrated the the symbolic and physical complexities of the processional

Germanic successes of the emperor Tiberius, who was also experience. The insertion of the Arch of Septimius Severus

strongly associated with Parthia.101 A third Parthian memory into the forum substantially altered movement along the

was evoked by the Arch of Augustus that flanked the Temple main imperial processional route, advancing straight from

of Divus Iulius. The large size of the new Severan arch, and the Temple of Divus Iulius along the front the Basilica

the inclusion of stairs in the central opening, impeded ve- Aemilia northwest toward the Severan arch.104 The stairs on

hicular access to the Rostra Augusti and Clivus Capitolinus the southeast side of the monument prevented the choreog-

thereby necessitating adjustments to the area, including the raphy of wheeled traffic passing through the dynastic arch.

reworking of the surrounding paving and the street ap- Instead, the elite participants in the funeral procession were

proaching from the east.102 now compelled to leave their vehicles and walk uphill

through the arch to approach the rear stairs of the rostra, or

to climb to the rostra by means of temporary wooden stairs

Case Study 3: The Funeral of Septimius Severus on the front; the latter was perhaps the better alternative.105

In 211 Septimius died in Eboricum (York) at the age of sixty-

six. His wife and their two sons Caracalla and Geta brought Alternative 1: Entry North of the Temple of Divus Iulius

his ashes to Rome and placed them in the Mausoleum of Two possible scenarios can be suggested for the parade chore-

Hadrian. Herodian records that an effigy of the dead em- ography (Figure 17). According to the first, the procession

peror was fashioned out of wax and laid atop an ivory couch entered the forum along the north side of the Temple of Divus

displayed before the imperial residence.103 For seven days Iulius (Figure 17a). After passing the temple’s flank, wheeled

doctors attended the effigy before proclaiming him officially vehicles lined up in front of the Basilica Aemilia or parked

dead; an apotheosis ceremony followed shortly. Dressed in temporarily in one of the side streets (Argiletum or Clivus

purple, the combative sons of Septimius led the funeral pro- Argentarius). The new co-emperors Geta and Caracalla, as

cession down from the Palatine and into the forum. Es- well as others who needed to ascend the rostra, walked

teemed young senators and equestrians followed, carrying through the Severan arch, turned left along the Clivus Capi-

the ersatz corpse to the Rostra Augusti. The voices of women tolinus, and then climbed the curved stairs of the Rostra

D e at h i n M o t i o n : F u n e r a l P r o c e s s i o n s i n t h e R o m a n F o r u m 27

JSAH6901_03.indd 27 2/2/10 5:20 PM

17a 17b 17c

Figure 17 Roman Forum of 211 CE. Alternative 1 (image © and courtesy of the Regents of the University of California, the CVRLab, and the Exper-

imental Technologies Center [ETC], UCLA) . See JSAH online for a bird’s-eye view of a real-time, three-dimensional model of the imperial Roman

Forum (211 CE) set in its geographic context. 17a View from in front of the Basilica Aemilia looking toward the Rostra Augusti and Arch of Septimius

Severus (17 a–c: images © and courtesy of the Regents of the University of California, the CVRLab, and the Experimental Technologies Center

[ETC], UCLA); 17b View of the Rostra Augusti from the north side of the Arch of Septimius Severus in front of the Temple of Concord; 17c View

from in front of the Temple of Saturn toward the Rostra Augusti and Arch of Septimius Severus

Augusti (Figure 17b). This choreography, however, was not Saturn), to approach the rear stairs of the Rostra Augusti.

ideal, since it hid these notables from the audience’s view for Elite participants mounted the platform, later rejoining the

a significant amount of time at a key moment in the event. A funerary retinue gathered below for the march to the

temporary wooden stairway may have provided direct access tomb.108

to the rostra front or to an adjacent temporary stage such as The kinetic viewsheds along these two possible proces-

that constructed for the funeral of Pertinax.106 Other parade sional routes differ significantly. Each affected the parade

participants dispersed into the crowd that gathered behind participants by drawing their attention to different referents.

the senators who, dressed in black, congregated (or sat) be- The first processional route along the Basilica Aemilia of-

fore the rostra. Alternatively, the parade may have passed fered internal views of the forum. The Temple of Jupiter

before the front of the rostra and then around the southwest Optimus Maximus, which had loomed above the smaller,

end of the speaker’s platform to reach the stairs at the rear more recessed basilicas flanking the forum in the mid-repub-

(Figure 17c). lic, was now hidden from view by the towering verticality of

the enormous Basilica Iulia. The Arch of Septimius Severus

Alternative 2: Entry South of the Temple of Divus Iulius directly ahead defined the end of the imperial Sacra Via, its

It is also possible that the parade entered the forum on the front-facing billboard-like façade celebrating not only the

southwestern side of the Temple of Divus Iulius moving emperor’s military successes, but also the dynasty he estab-

through the Arch of Augustus and then along the road in lished (see Figure 17a).109 As they moved farther into the

front of the Basilica Iulia (Figure 18).107 Following this path forum, the imperial heirs at the head of the cortege would

the procession turned right in front of Tiberius’s arch have been drawn toward the rostra, attracted in part by the

(viewed to the left between the basilica and the Temple of mournful songs and white robes of the singers on the

28 j s a h / 6 9 : 1 , m a r c h 2 010

JSAH6901_03.indd 28 2/2/10 5:20 PM

18a

18b

18c 18d 18e

Figure 18 Roman Forum of 211 CE. Alternative 2. See JSAH online for a bird’s-eye view of a real-time, three-dimensional model of the imperial

Roman Forum (211 CE) set in its geographic context (18a–e: images © and courtesy of the Regents of the University of California, the CVRLab, and

the Experimental Technologies Center [ETC], UCLA). 18a View through the Arch of Augustus looking toward the Basilica Iulia and the Temple of

Saturn; 18b View from in front of the Basilica Iulia. Beyond the Temple of Saturn rises that of Vespasian and Titus, with the Severan inscription

(see inset); 18c View from the south corner of the Rostra Augusti looking north toward the Arch of Septimius Severus with “parthico” inscription;

18d View from the balcony of the Basilica Iulia looking north toward the Arch of Septimius Severus with the statue of Trajan atop his honorific column

visible in the distance; 18e View from in front of the Rostra Augusti looking up toward the Arch of Septimius Severus

D e at h i n M o t i o n : F u n e r a l P r o c e s s i o n s i n t h e R o m a n F o r u m 29

JSAH6901_03.indd 29 2/2/10 5:21 PM

bleachers. The sea of black-garbed senators in front of the The views of the arch observed by the procession were

choir provided a neutral base above which they could see the compelling, suggesting that the monument was specifically

honorific columns erected by Septimius on the rostra, the designed to interact with the funeral, a hypothesis that requires

Temple of Saturn housing the state treasury, and farther a further investigation of its place in imperial history. The death

back, the Temple of Vespasian restored by the deceased. of an emperor always entailed great difficulties, and it was Au-

If the pompa funebris followed the second route, entering gustus who first decided to plan ahead in monumental fashion.

the forum through the Arch of Augustus south of the Temple As early as 28 BCE, in his sixth consulship, Octavian, not yet

of Divus Iulius, however, a related but different panorama of Augustus, established a dynastic funerary tradition by building

imperial imagery unfolded before the viewer. Those who a monumental family tomb, the so-called Mausoleum.116 But

passed along the road in front of the Basilica Iulia would have it was much more. In name and form it recalled funerary mon-

faced the Temple of Vespasian; the Temple of Saturn partially uments of the east and in so doing advertised his victory, oper-

blocked the view of the facade, leaving visible a potent word ating as a Mausoleum-Tropaeum, a “tomb and trophy.”117

in the lowest line: severus (Figure 18b).110 The visually and In the first century CE Domitian erected a commemo-

programmatically rich Rostra Augusti to the right would rative arch for his elder brother, the emperor Titus, south-

soon draw their gaze, with the broad Temple of Concord east of the forum. Although not specifically celebrating a

rising behind, evoking Severan claims of state and dynastic triumph, the memorial drew upon triumphal associations,

harmony. Simultaneously the great Severan arch loomed to- while simultaneously underscoring dynastic continuity and

ward the north.111 In fact, to view the rostra from this route reminding viewers of the donor’s quasi-divine status as

demanded that one view the arch as well. Although too dis- brother of a god. Celebrating the achievements of the de-

tant to be read in detail, the great panels on the arch evoked ceased, the arch echoes the funerary practice of presenting

the well-known spiral narratives on the columns of Trajan a res gestae (list of accomplishments).118

and Marcus Aurelius (Figure 18c). This association was re- While the funerary function of the Arch of Titus is ques-

inforced for viewers on the southwest side of the forum in tionable, that of the Column of Trajan is not. Whether it was

front of the Basilica Julia; far in the distance they could see envisioned as a tomb from the beginning, this memorial of

Trajan’s statue atop his column (Figure 18d).112 Moving to- the successful Dacian campaign certainly functioned as one

ward the rostra this visual link was soon obstructed by the when Trajan’s ashes were placed within a chamber in the

impressive Severan arch (Figure 18e). base.119 The Arch of Septimius Severus follows the tradition

Following the disruptions that preceded his accession to started with these imperial memorials. It was built as a tri-

power, Septimius had been anxious to secure his position by umphal trophy, but this function was compromised by the

associations with revered past dynasties and to lay the stairs on the forum side, which prevented a triumphing gen-

groundwork for future stability.113 By erecting his monument eral in his gilded chariot from passing through the central

after a long hiatus in new building additions to the forum, he opening. The arch also served specific propagandistic pur-

established a clear association with earlier Julio-Claudian poses: it was both an advertisement for dynastic continuity

projects. The Severan arch responds directly to the Arch of and a visual res gestae in the style of the Column of Trajan.120

Augustus that stood diagonally across the forum, south of the During the Republic, Romans visually represented con-

Temple of Divus Iulius, and which similarly honored suc- tinuity by parading their revered ancestors from various

cesses in Parthia.114 Just as Trajan, Marcus Aurelius, and Lu- centuries. Roman emperors continued to honor illustrious

cius Verus, Septimius was given the name Parthicus. A predecessors with displays of the state’s viri illustres at their

literate observer viewing the funerary events at the rostra funerals. On other days of the year, they relied on forged

would doubtless note the bronze inscription parthico re- visual connections among imperial monuments, especially

peated on the upper corners of the arch attic. Like the tri- among funerary memorials, to affirm their ties to past rulers.

level relief, the reference was a verbal extension of the For example, an elite observer who climbed the Column of

Column of Trajan in the distance (see Figure 18d). Whereas Marcus Aurelius exited the door on top to face the mausolea

the column depicted the Dacian conquest, the arch reminded of Augustus and Hadrian.121 While no ancient references

knowledgeable viewers that Trajan’s Parthian conquest was describe exactly who was allowed to ascend to such heights

short-lived and that it was Septimius Severus who ultimately and see the visual lines that were drawn between Rome’s

completed the task begun years before. The recorded date imperial funerary monuments, the architectural accommo-

for Severus’s Parthian triumph was 28 January 198 CE, the dation of such elite viewing affirms its significance.

same day as the dies imperii of Trajan (when he was officially The Arch of Septimius Severus participated in similar

proclaimed emperor in 98 CE, one hundred years earlier).115 visual interconnectivity. An internal stair led to chambers in

30 j s a h / 6 9 : 1 , m a r c h 2 010

JSAH6901_03.indd 30 2/2/10 5:21 PM

Figure 19 View from walkway on the Arch of Septimius Severus toward Figure 20 View from upper portico of the Basilica Aemilia looking

the Capitoline (image © and courtesy of the Regents of the University of toward the Arch of Septimius Severus and Temple of Concord (images

California, the CVRLab, and the Experimental Technologies Center [ETC], © and courtesy of the Regents of the University of California, the CVR-

UCLA). See JSAH online for an analogous view keyed to a real-time, Lab, and the Experimental Technologies Center [ETC], UCLA). See

three-dimensional model set in its geographic context JSAH online for an analogous view keyed to a real-time, three-dimen-

sional model set in its geographic context

the attic and to an external walkway at the same level protected of the siting and program fully comprehensible. In particular,

by a metal balustrade.122 From this vantage point, a privileged the orientation of the arch approximately parallel to the rostra

imperial observer had a view over the entire Forum Roma- is seen to have created a formal tableau that concretized the

num, a panorama almost on a par with that seen by the gods. status-associated frontal view appreciated by the Romans.

He could easily observe the Arch of Titus to the southeast and The result is evident in a relief on the Arch of Constantine

the Column of Trajan to the north. However, his view of the (see Figure 14). The artist shows the emperor performing an

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline was oratio from atop the rostra, flanked by the Arch of Tiberius to

fragmentary and oblique (Figure 19). After all, since that tem- the left and the Arch of Septimius to the right. The two impe-

ple had originated in the Republic and undergone numerous rial memorials form potent bookends that eliminate the need

rebuildings by various patrons, it did not belong among the to represent other buildings.124 Significantly, the Basilica Iulia

visually interconnected imperial memorials that honored in- is added to this panorama, an affirmation of both the build-