Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems

Transféré par

Rudi IlhamsyahCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems

Transféré par

Rudi IlhamsyahDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Original Articles 99

Attitude of Physicians Towards

Automatic Alerting in Computerized

Physician Order Entry Systems*

A Comparative International Survey

M. Jung1; A. Hoerbst1, 2; W. O. Hackl1; F. Kirrane3; D. Borbolla4, M. W. Jaspers5;

M. Oertle6; V. Koutkias7; L. Ferret8, 9; P. Massari10; K. Lawton11; D. Riedmann1;

S. Darmoni10; N. Maglaveras7; C. Lovis12; E. Ammenwerth1

1Instituteof Health Informatics, Department of Biomedical Informatics and Mechatronics, UMIT – University for

Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Hall in Tirol, Austria; 2Research Division for eHealth and Tele-

medicine, UMIT – University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Hall in Tirol, Austria; 3Depart-

ment of Medical Physics and Bioengineering, Galway University Hospital, Galway, Ireland;4Health Informatics Depart-

ment, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires City, Argentina; 5Centre for Human Factors Engineering of

Health Interactive Technology (HIT-lab), Department of Medical Informatics, Academic Medical Center – University of

Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 6Medical Informatics and Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital of

Thun, Thun, Switzerland; 7Lab of Medical Informatics, Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece;

8Pharmacy Department, Hospital of Denain, Denain, France; 9 EA2694, University Hospital of Lille, Lille, France; 10 CIS-

MeF & TIBS team, LITIS EA 4108, Rouen University Hospital, Normandy, France; 11IT, Medical Technology and Teleph-

ony Services of Capital Region, Copenhagen, Denmark; 12Division of Medical Information Sciences, University Hospi-

tals of Geneva and University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

Keywords 2,600 physicians in eleven hospitals from nine benefits of alerting in CPOE systems on

Medical order entry systems, clinical decision countries to participate. Eight of the hospitals medication safety. However, alerting should

support systems, attitude, questionnaires, had different CPOE systems in use, and three be better adapted to the clinical context and

alerting of the participating hospitals were not using a make use of more sophisticated ways to

CPOE system. present alert information. The vast majority

Summary Results: 1,018 physicians participated. The of physicians agree that additional informa-

Objectives: To analyze the attitude of phys- general attitude of the physicians towards tion regarding interactions is useful on de-

icians towards alerting in CPOE systems in CPOE alerting is positive and is found to be mand. Around half of the respondents see

different hospitals in different countries, ad- mostly independent of the country, the spe- possible alert overload as a major problem;

dressing various organizational and technical cific organizational settings in the hospitals in this regard, physicians in hospitals with

settings and the view of physicians not cur- and their personal experience with CPOE sys- sophisticated alerting strategies show partly

rently using a CPOE. tems. Both quantitative and qualitative results better attitude scores.

Methods: A cross-sectional quantitative and show that the majority of the physicians, both Conclusions: Our results indicate that the

qualitative questionnaire survey. We invited CPOE-users and non-users, appreciate the way alerting information is presented to the

physicians may play a role in their general at-

titude towards alerting, and that hospitals

Correspondence to: Methods Inf Med 2013; 52: 99–108

with a sophisticated alerting strategy with

Alexander Hoerbst, PhD doi: 10.3414/ME12-02-0007

Eduard Wallnoefer Zentrum 1 received: June 1, 2012 less interruptive alerts tend towards more

6060 Hall in Tirol accepted: September 10, 2012 positive attitudes. This aspect needs to be

Austria prepublished: November 27, 2012 further investigated in future studies.

E-mail: alexander.hoerbst@umit.at

1. Introduction cation errors, and a majority of ADEs, Entry (CPOE) systems have shown the po-

occur during the prescription phase of the tential to reduce medication errors as well

Medication errors and adverse drug events medication cycle [3 –5]. as ADEs [6]. CPOE systems may be

(ADEs) are serious hazards for patients all Amongst other approaches, the Institute coupled with Computerized Decision Sup-

over the world. Reports of the Institute of of Medicine recommends the use of infor-

Medicine (IOM) estimate that a patient in mation and communication technology

an US-hospital faces at least one medi- (ICT) in order to improve medication * Supplementary material published on our website

cation error per day [1, 2]. Most medi- safety [1]. Computerized Physician Order www.methods-online.com

© Schattauer 2013 Methods Inf Med 2/2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

100 M. Jung et al.: Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems

port (CDS) systems [7], an approach that positive alerts or non-patient-tailored 2. Study Question

has proven to be even more effective in re- alerts may annoy the clinicians [13]. Fur-

ducing medication errors [6]. thermore, recent research [13–21] under- What is the attitude of physicians towards

However, recent research found that the lines the importance of accounting for alerting in CPOE systems in different hos-

introduction of a CPOE system can also socio-technical issues and claim that a suc- pitals from different countries, taking into

have a negative impact in patient safety [8] cessful CPOE implementation “often is account the different organizational and

and lead to unintended and unanticipated more influenced by the organizational set- technical settings and also addressing the

negative effects such as an increase in the ting than the specificities of the CPOE view of physicians not currently using a

risk of medication errors [9], or worse, in system itself ” [11]. CPOE?

mortality [10]. Campbell et al. identified Various studies have tried to measure

nine types of these unintended adverse the attitude of physicians towards CPOE

consequences after CPOE introduction, systems in general and towards alerting in 3. Methods

such as workflow issues or emotional as- particular [22–31]. These studies have

pects [11]. In a related study, Sittig et al. fo- mostly been conducted in single hospitals, 3.1 Study Context

cussed on those emotional responses to the or in hospital groups using the same CPOE This international study was conducted in

CPOE system and reported that negative systems. However, the organizational set- ten European and – to provide a compari-

emotions, for example anger or annoyance, tings surrounding CPOE implementations son outside of Europe – one South-Ameri-

“were by far the most prevalent”. They con- usually differ between hospitals. Hence, can hospital. We directed the survey to-

cluded that if those aspects were not ad- one could assume that the attitude of the wards both university hospitals and general

dressed properly, system implementations physicians towards CPOE, and especially hospitals (▶ Table 1).

could fail or CPOE systems would not be towards alerting, would be different when Three hospitals had not implemented

routinely used [12]. comparing different hospitals with differ- CPOE systems (Feldkirch, Rouen, Thessa-

The design and usability of the system ent CPOE systems from different coun- loniki). Eight hospitals were using a CPOE

seem to play a decisive role in the phy- tries. Furthermore, we assume that this at- system from different vendors with varying

sicians’ attitude towards CPOE. In their titude may depend on the personal experi- levels of CDS. ▶ Table 2 shows more details

systematic review, Khajouei and Jaspers ence with CPOE. However, these points on the CDS levels. In the following para-

identified nine CPOE specific design as- have not to date been systematically inves- graphs, we describe the CPOE systems in

pects that influence the ease of use and tigated in a multi-centric international use in more detail. For this description, we

workflow. In particular, the design of alerts study. make the following definitions:

has a significant impact on the physicians’ • Automatic alerts are those that are trig-

attitudes, as for example too many false- gered and presented automatically to

the user.

• Optional alerts require a specific user

Table 1 action to trigger the alert, for example

Hospital(s) Type of Hospital Beds

Key data of the partici- by clicking a specific button (such as

AMC Amsterdam (Nether- University hospital 1,002 pating eleven hospi- ‘check prescription’).

lands) tals • Interruptive alerts define those alerts

HIBA Buenos Aires (Argentine) University hospital 750 that in some way intercept or interrupt

Copenhagen hospitals General hospitals 1,407 the prescription workflow process, and

(Denmark) force a user action to proceed (e.g. to

(Glostrup, Herlev, Hillerød) change a certain prescription item be-

CH Denain (France) General hospital 600 fore a user can finalize this prescrip-

tion).

LKH Feldkirch (Austria) General hospital 606

• Non-interruptive alerts do not inter-

UHG Galway (Ireland) University hospital 885 cept or interrupt the prescription work-

HUG Geneva (Italy) University hospital 1,915 flow process. The alert content is pres-

CHU Rouen (France) University hospital 2,303 ented only for information purposes

(e.g. the system indicates/informs that

USHATE Sofia (Bulgaria) Specialized university hospital 109

there are possible drug-drug interac-

for endocrinology

tions, but does not require the user to

Thessaloniki hospitals (Greece) 1 general hospital, 2 university 2,148 change prescription items or to ac-

(AHEPA, Ippokrateio, hospitals

knowledge the alert explicitly).

Panageia)

Spital STS AG Thun General hospital 300

(Switzerland)

Methods Inf Med 2/2013 © Schattauer 2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

M. Jung et al.: Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems 101

Table 2 Categorization of the CDS features of the CPOE systems in use according to the classification of Kuperman et al. [32]. ü= CPOE offers the de-

scribed functionality. CDS features labeled with a * are not consistently offered (e.g. only in some departments).

Amster- Buenos Copen- Denain Galway Geneva Sofia Thun

dam Aires hagen

Basic CDS functionalities

Drug-allergy checking ü ü ü ü

Basic dosing guidance ü ü ü ü ü ü*

Formulary decision support ü ü ü

Duplicate therapy checking ü ü ü ü ü ü

Drug-drug interaction checking ü ü ü ü ü ü

Advanced CDS functionalities

Advanced dosing guidance ü ü* ü*

Guidance for medication-related laboratory testing ü* ü*

Drug-disease contraindication checking ü*

Drug-pregnancy checking ü*

3.1.1 Amsterdam 3.1.3 Copenhagen ports locally customized clinical pathways

with pre-configured drug protocols. In ad-

The commercial CPOE system Medicator/ The commercial CPOE system EPM (Ac- dition, further information on all drugs, in-

ESV (iSoft) has been used across all clinical cure/IBM) was introduced in the partici- cluding policies and procedures, are avail-

departments since 2004, except for the pating study hospitals between 2006 and able via a link to an intranet site managed

ICU, which uses a different system. It is 2009. The system is integrated with the re- by the clinical pharmacists.

connected to the pharmacy drug database gional pharmacy database and drug for-

and the national drug database and offers mularies and allows for regional and local

3.1.6 Geneva

links to drug formularies, handbooks, customized clinical pathways with pre-

protocols, and intra- and internet appli- configured drug protocols. All alert are The homegrown CPOE system Presco has

cations. It also support order sets. All alerts automatic and interruptive. Additional in- been in use since 2002. It is used across the

are automatic and interruptive. The alerts formation on a particular drug is available eight HUG hospitals, except for the inten-

only present the most important informa- on demand. sive care units (ICU), which uses a different

tion; detailed information is available on CPOE system. The system is linked to the

demand. official Swiss drug database. It is highly

3.1.4 Denain

adapted and customized to different as-

The CPOE module of the commercial pects; there is general decision support for

3.1.2 Buenos Aires

clinical information system DxCare (Me- the entire organization as well as special-

The CPOE module of the homegrown dasys) has been in use since 2003 and is ized decision support for single divisions,

clinical information system Italica was im- connected to the commercial drug data- diseases and procedures. Depending on the

plemented in 1999 in the outpatient set- base of Vidal. All alerts are optional and in- individual type of CDS, different triggering

ting. It is based on a self-developed drug- terruptive. Furthermore, the user can ac- and presentation strategies are used. Fur-

drug interaction knowledge database. High cess comments on the prescriptions made thermore, the CPOE system supports clini-

severity alerts and duplicate drug alerts are by the pharmacist. cal pathways and guidelines. Appropriate

automatic and interruptive. All other alerts committees define all functionalities and

are indicated in a non-interruptive way by parameters.

3.1.5 Galway

a red flag next to the order and can be ac-

cessed optionally. In addition, a drug com- The CPOE module of the commercial

3.1.7 Sofia

pendium for drug related information can clinical information system Metavision

be accessed directly from the prescription (iMDSoft) has been in use since 2005. All The CPOE system Medica was developed

screen. alerts are automatic, but only interruptive with a company (Macrosoft) in 2010. It

for the most important issues. All other offers automatic and interruptive alerts for

alerts are non-interruptive and shown as dosage support across the entire hospital.

information notices. The system also sup-

© Schattauer 2013 Methods Inf Med 2/2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

102 M. Jung et al.: Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems

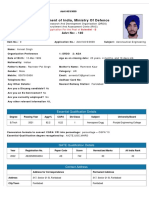

Table 3 Sampling details of the participating study hospitals

Hospital Type of Contacted Departments Physician Contacted Valid Return

Questionnaire Sample Physicians n (%)

Amsterdam Electronic All departments using CPOE Full sample 217 78 (35.9%)

Buenos Aires Electronic Family medicine Full sample 110 47 (42.7%)

Copenhagen Paper-based Anesthesia, gastro-surgery, internal medicine Convenience 207 94 (45.4%)

sample

Denain Paper-based All departments Full sample 60 26 (43.3%)

Feldkirch Paper-based Internal medicine, psychiatry, surgery, urology Convenience 30 18 (60%)

sample

Galway Electronic Anaesthesia, cardiothoracic surgery, critical care Full sample 22 22 (100%)

Geneva Electronic All departments using CPOE Full sample 1,585 552 (34.8%)

Rouen Electronic All departments Convenience 100 41 (41%)

sample

Sofia Paper-based All departments Full sample 53 31 (58.5%)

Thessaloniki Electronic All departments (mostly pediatrics) Convenience 110 72 (65.5%)

sample

Thun Electronic Gynecology, internal medicine, obstetrics, orthopedics, surgery Full sample 106 37 (37%)

All available alert information is presented 3.1.9 Feldkirch, Rouen and Thessa- hagen, Feldkirch, Rouen and Thessaloniki,

at once. loniki we contacted a convenience sample of

physicians. For the number of contacted

Medication ordering is still paper-based in physicians, see ▶ Table 3.

3.1.8 Thun

these hospitals. We included them in the

The CPOE module of the commercial survey to measure the attitudes of CPOE

clinical information system Phoenix ‘non-users’. 5. Survey Instrument

(CompuGroup) was introduced in 2003,

followed by extensive in-house develop- The survey was conducted in either paper-

ment. It is used across the hospital, except 4. Study Design and based or web-based format (using Lime-

for the ICU, which uses another CPOE sys- Participants Survey), and each hospital was free to

tem. The system is linked to the official choose their preferred format. The survey

Swiss drug database. Drug interaction We performed a cross-sectional quanti- content was the same for all participating

checks are triggered automatically, but can tative and qualitative questionnaire survey. hospitals, and provided in three parts:

also be triggered optionally. Drug interac- The study design was presented to the

tion alerts for higher severities are inter- ethics committee at UMIT. The committee 5.1 Part 1: Attitudes of the

ruptive. Alerts for lower severity are sup- did not consider a formal approval of the Physicians

pressed and only presented on demand design necessary. Further approval was ob-

(optional alert). The amount of informa- tained from the local hospital management We selected eleven survey items from exist-

tion presented to the user depends on the as required. ing surveys in the prevailing literature that

severity of the alert. Drug interaction alerts For the Denain and Sofia sites, we con- measured the attitudes of physicians to-

for oral anticoagulants are automatic, but tacted all physicians in all clinical depart- wards CPOE systems and alerting [22–24].

non-interruptive. Drug-allergy alerts are ments. In Amsterdam, Galway, Geneva and By a group discussion, survey items that

automatic and interruptive. Dosing guid- Thun, we contacted all physicians who matched to the objectives of the current

ance alerts are automatic, but non-inter- were identified as current users of the survey were selected. We adapted the

ruptive. CPOE system. For Buenos Aires, as the wording of the items to fit the organiza-

CDS functionality of the CPOE system was tional context in each hospital (e.g. adding

solely used in the outpatient clinics, we the name of the local CPOE system). Fur-

only contacted the physicians in the family thermore, we formulated four additional

medicine department, as this was the sole statements regarding the scope of alert

outpatients-only department. In Copen- overload, alert filtering, alert presentation

Methods Inf Med 2/2013 © Schattauer 2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

M. Jung et al.: Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems 103

and expenditure of time. The order of the the points and compared them between the (question 2) and may help to reduce pre-

statements was randomized to avoid an hospitals using box plots. The statistical scribing errors (question 7). In addition,

unintentional ‘serial position effect’. All 15 analysis was performed with the software for most of the hospitals, a majority stated

items were scaled with a 4-point Likert tool SPSS™ Statistics 20 (IBM). that their initial prescribing decision may

scale. A list of the questions can be seen in The answers to the free-text question be influenced by the alerts (question 15),

▶Figure 1 and in ▶Supplementary Online were analyzed by quantitative content without, however, limiting their freedom of

File 1. analysis with inductive category devel- taking prescribing decision (question 13).

opment according to Mayring [33] by two Conversely, for half of the hospitals, a

5.2 Part 2: Benefits and Problems researchers using the software tool majority of the physicians thought that

of Automatic Alerting MaxQDA 10™ (Verbi GmbH). The fre- CPOE systems with automatic alerting

quencies of each category were normalized would trigger too many irrelevant alerts

In two free-text questions, we asked the according to the sample size of each hospi- (question 14). However, except for two

physicians to detail what they considered tal, summed up and visualized by tag hospitals, the physicians, in most part, did

the largest benefits and the biggest prob- clouds using the web tool Wordle™ (Jona- not think that reacting to alerts would cost

lems of an automatic alerting functionality than Feinberg). them too much time (question 4). In al-

in CPOE systems. most all hospitals, the majority of the

physicians disagreed with the statement

5.3 Part 3: Personal Details 7. Results that automatic alerts would only provide

the physicians with information they al-

We asked the physicians to provide demo- 7.1 Participants ready knew (question 9). The majority also

graphic data about their age, sex, profes- We distributed 2,600 questionnaires, of disagreed that automatic alerts would be

sional role, years of work experience, and which 1,018 were returned complete. Due essentially meaningless and a waste of time

years of experience with CPOE systems. to different sampling strategies, the return (question 3).

The questionnaire was pre-tested with rate differed from 34.8% in Geneva to A large majority of the hospitals sur-

seven doctors from different specialties. It 100% in Galway (▶ Table 3). Across all veyed thought that it would be useful if the

was then translated into Bulgarian, Danish, hospitals, a balanced number of male and CPOE system provided more information

Dutch, French, German, Greek and Span- female physicians responded. In almost all on a drug-drug-interaction if the user de-

ish. The questionnaires were then again hospitals, the median age category was manded it (question 10) and that it should

pre-tested in each hospital with two or 30–39 years (40 –49 years in Denain and be more difficult to override lethal drug-

three doctors. The study was conducted Rouen). In Denain, Galway and Rouen, the drug interactions (question 6). However,

between the second quarter of 2010 and physicians’ positions on an average were on they were rather undecided, whether or not

the first quarter of 2012. a high level in the hierarchy; in Feldkirch to be obliged to enter a reason for overrid-

and Thessaloniki, on a low level; and in all ing serious drug-interaction alerts (ques-

other hospitals, on a medium level. In most tion 8).

6. Methods for Data of the hospitals, the average time the phys- With regard to the presentation of the

Analysis icians had worked was 10 –15 years; in alerts, for all hospitals, a majority of the

Rouen it was 17 years; and in Feldkirch and physicians strongly agreed that there

We calculated the frequencies and pre- Thessaloniki, it was 3 and 5 years, respect- should be a greater distinction between im-

sented the data using condensed bar charts. ively. In the hospitals with a CPOE system, portant and less important drug-drug in-

To validate the 15 items and to elicit the physicians had worked, on average, be- teractions (question 11) and that the alerts

single latent variables that would allow for tween 3 –7 years with the CPOE system. should be filtered according to the clinical

calculating certain attitude scores, we then context (question 5). Furthermore, in most

performed a factor analysis on all answers 7.2 Study Findings hospitals, a majority of the physicians

from all hospitals (using Principal Compo- wished that automatic alerts should be

nent Analysis PCA and Varimax rotation 7.2.1 General Attitudes towards solely presented in an informative and

techniques). For each identified factor, we Alerting non-interruptive way (question 12).

performed a reliability analysis and then ▶Figure 1 illustrates the answers to the 15

calculated an additive score using the fol- questions. Detailed frequency values for

7.2.2 Results of the Factor Analysis

lowing scoring scheme: Disagreement = 1 each question and hospital are provided in

point; partial disagreement = 2 points; par- ▶Supplementary Online File . To test whether our data was suitable for a

tial agreement = 3 points; agreement = 4 For all hospitals surveyed, a large major- factor analysis, we performed a Kaiser-

points. Missing values (e.g. ‘no statement’ ity of the physicians replied that automatic Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling

answers) were replaced by the factor’s alerts would be a useful tool in prescribing adequacy as well as Bartlett’s test of sphe-

median score of the corresponding phys- (question 1), that their CPOE systems had ricity. The KMO coefficient was 0.78 and

ician. For every physician, we summed up the capacity to improve prescribing quality the significance of Bartlett’s test was

© Schattauer 2013 Methods Inf Med 2/2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

104 M. Jung et al.: Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems

Figure 1 Relative frequencies of the answers to the 15 items from all hospitals. The hospitals without a CPOE system are indicated with grey letters. ‘No

▶

statement’ answers are not illustrated. Detailed frequency values are supplied in Supplementary Online File.

smaller than 0.01%, indicating that our

data was suitable for performing a factor

analysis. From the factor analysis, we could

elicit two factors. The reliability analysis of

these factors yielded Cronbach’s Alphas

(internal consistency) of α1 = 0.79 for the

first factor, and α2 = 0.44 for the second fac-

tor. As the internal consistency of the sec-

ond factor was too low (< 0.5), we only

took the first factor into account, which

consists of eight items (Items number 1, 2,

3, 4, 7, 9, 13 and 14, compare ▶ Figure 1/

Supplementary Online File ). In regard to

the content of these items, we labeled these

factors ‘usefulness of alerts’. The power of

all items was sufficiently high; deleting one

of the items would not have resulted in a

higher internal consistency. We then calcu-

lated a sum score of this factor for each

participant.

Regarding this identified factor, all hos-

pitals – also those without a CPOE sys-

tem – show positive tendencies on a scale

Figure 2 Box plot of the sum scores of the factor ‘usefulness of alerts’ (based on the items 1, 2, 3, 4, from 8 (minimum score) to 32 (maximum

7, 9, 13, 14). The hospitals without a CPOE system are indicated with white boxes. The maximum score

score) and have median scores between 23

to reach was 32 points; the minimum score was 8 points. The horizontal dotted line indicates the ‘neu-

tral’ mean of 20 points. Scores below this line indicate negative attitudes; scores above this line indicate

(Copenhagen and Denain) and 30 (Gal-

positive attitudes. way). Almost all hospitals have an inter-

quartile range (IQR) settled solely in the

positive area. Only three hospitals had

positive or neutral scores without negative

outliers (▶ Figure 2).

Methods Inf Med 2/2013 © Schattauer 2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

M. Jung et al.: Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems 105

7.2.3 Qualitative Results

Overall, the physicians provided 679 free-

text statements to the question of the big-

gest benefits and 652 statements to the

question of the biggest problems of auto-

matic alerting. The inductive categoriz-

ation resulted in 38 categories of benefits

and 24 categories of problems. The quanti-

tative content analysis indicated that the

prevention of serious errors, safer prescrip-

tions and patient safety in general, were

perceived as the major benefits of an auto-

matic alerting functionality. Other fre-

quently nominated benefits included the

Figure 3 Tag clouds of the benefits (green) and problems (red) of automatic alerting as named by the

reminder functionality, along with the re- physicians. Bigger letters indicate higher relative frequencies (normalized with regard to the different

duction of general errors, interactions and sample sizes). The biggest tag in the benefits cloud ‘prevention of serious errors’ was mentioned 88

ADEs. For the perceived major problems of times. The biggest tag in the problems cloud ‘time consumption’ was mentioned 138 times.

an automatic alerting functionality, the

analysis indicated time consumption, alert

overload, irrelevant alerts as well as alert fa- fected by this problem, but that for those 8.2 Strengths and Weaknesses

tigue. Other frequently reported problems the problem is seen as very severe.

were slower prescriptions, missing contex- All hospitals have a comparable, mostly This study was not designed to identify and

tualization of the alerts, and perceived positive, general attitude towards auto- quantify factors that influence the CPOE

over-reliance on technology. A high matic alerts (▶ Figure 1) and a clear posi- attitude of physicians, or to quantify the

number of physicians claimed that they tive attitude towards the factor ‘usefulness objective impact of automatic alerts. We

would not see any problems with auto- of alerts’ (▶ Figure 2). In general, we also did neither evaluate the perceptions of

matic alerts (▶ Figure 3). found that the attitudes of the CPOE users other care providers, such as nurses, or of

and CPOE non-users did not differ in gen- patients nor did we take patient outcome

eral (▶ Figure 1) and specifically not re- criteria into account. We focused on

8. Discussion garding the factor ‘usefulness of alerts’ measuring the impact as perceived by the

(▶ Figure 2). One explanation for this find- physicians, and on comparing the attitudes

8.1 Answers to the Study ing could be based on the similarities in the towards CPOE in various settings.

Question clinical work patterns and the common The survey reflects an international

Both quantitative and qualitative results understanding of the physicians concern- focus and includes physicians from a range

show that the majority of the physicians ing patient safety and quality of care, irre- of hospitals of different size and with vari-

appreciate the benefits of alerting in CPOE spective of the computerization of the pre- ous CPOE settings, including non-CPOE

systems by providing for safer prescriptions scribing process. settings. We focussed mostly on European

through the reduction of errors, especially The three hospitals with the highest hospitals, the results may not be transfer-

the most severe ones and, hence, a general scores, Buenos Aires, Galway and Thun able to other areas. In general, the response

increase in patient safety. However, alerting (▶ Figure 2), use more sophisticated alert- rates were quite high (35% –100%) and

should be better adapted to the clinical ing strategies, which only interrupt the overall, more than 1,000 physicians partici-

context and make use of more sophisti- physicians for the more important and se- pated in this survey. Limitations include

cated ways to present alert information. vere warnings [34, 35]. The CPOE-using use of a convenience sample of hospitals

The physicians also wish for less interrup- hospitals with the lowest scores, Copen- and, furthermore, potential recruitment

tive alerts that are prioritized to avoid pos- hagen and Amsterdam, only offer auto- biases due the convenience sampling of

sible overload of irrelevant alerts that may matic and interruptive alerts. Sofia also physicians are possible in Copenhagen,

lead to alert fatigue. Interestingly, in almost makes use of such alerts. However, they Feldkirch, Rouen and Thessaloniki. Due to

all hospitals, the majority of the physicians only provide alerts for dosage adaptations, the sampling strategy and the voluntary

did not think that automatic alerts would which are much less in number and prob- nature of this survey, the participants can-

cost them too much time, despite time con- ably perceived highly relevant due to the not be seen as fully representative for all

sumption was the most frequently nomi- specialty of the hospital. hospital physicians. Also a lower/higher

nated problem with automatic alerts in the rate of participating physicians in the

free-text comments. One reason may be samples with a basic more negative/posi-

that only a minority of physicians is af-

© Schattauer 2013 Methods Inf Med 2/2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

106 M. Jung et al.: Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems

tive attitude towards alerting cannot be ex- cians in our survey is widely discussed in order to prioritize and filter irrelevant

cluded. the literature [13, 24, 30, 36 –39]. This issue alerts is relatively innovative and is de-

Non-professional translators who were shows similarities with the prevailing re- scribed in more detail by Riedmann, Jung

familiar with the field carried out the trans- search on the risks associated with the de- et al. [45, 46]. Further innovative ap-

lation of the questionnaire. A multi-stage sign and use of medical device alarms in proaches towards better-adapted alerting

process including back-translation was not hospitals, on nuisance effects and on prio- strategies are described in [13, 47–49].

conducted. Furthermore, it was necessary ritization [40, 41]. The objective of our

to make minor adaptations to the wording study, however, was not to derive specific

of the questions to fit the local conditions actions to overcome this issue. Regarding 9. Meaning and Generaliz-

of each hospital. the question of whether or not automatic ability of the Study

The factor analysis resulted in one factor alerts would cost too much time, we found

with a very high internal consistency. a discrepancy in the literature, as we did In general, the attitudes of the physicians

between our quantitative and qualitative towards CPOE and alerting were positive.

8.3 Results in Relation to Other data. On the one hand, Holden found that Also the CPOE non-users showed positive

Studies the clinicians’ time was ‘better spent in attitudes, though their surveyed population

other ways’ and that CPOE was perceived was small (n = 131). We could not find ob-

Most of our results are in-line with the as a ‘threat to efficiency’ [27]. On the other vious differences between the hospitals

findings of the evaluation studies our sur- hand, Sittig et al. found that CDS in CPOE with or without a CPOE system, or be-

vey instrument is based on [22–24], as well would be ‘worth the time it takes’ [31] and tween those with a commercial or home-

as with other surveys results reported in Weingart et al. even found an increase in grown CPOE system, and we could not see

the literature (see below). However, to our the physicians’ perceived efficiency by an influence of the duration of the CPOE

knowledge, this is the first broader inter- e-prescription [30]. Our findings that the usage or the working experience of the

national CPOE survey addressing phys- physicians perceived that alert content pro- physicians. What we could observe is that

icians in various countries and also includ- vided more than just ‘known information’, the chosen alerting strategy (e.g. which

ing CPOE non-users. No studies are which would therefore not make the alerts kind of alerts are interruptive) may have an

known to us that specifically compare the a waste of time per se, were supported by influence on the physicians’ attitudes to-

physicians’ attitudes towards CPOE alert- Ko et al. [23]. Overall, the efficiency of ward CPOE alerting and especially on the

ing in various technical and organizational CPOE systems can be improved when the perception that too many irrelevant alerts

settings or which try to quantify factors specificity and sensitivity levels of their ad- are being displayed.

that influence these attitudes. vice increase [42]. The problems identified in our survey

Comparable to our results, the physi- The physicians questioned in other sur- center on the perceived overload of irrel-

cians surveyed by Magnus et al. and Hor et veys wished for more on-demand informa- evant alerts leading to alert fatigue and loss

al. also stated that alerts could be a useful tion on an alert [24] and thought that it of time. Consequently, a large majority of

tool [24], reminder functionality as a kind would be necessary to make overrides of participants in all hospitals wished for a

of memory support, which was mentioned severe interactions more difficult [24, 28]. better distinction of the alerts according to

in the free text comment in our survey The latter finding is not supported by a sur- their importance in the clinical context.

(▶ Figure 2) as a benefit of automatic alert- vey by Ko et al., in which the physicians re- The three hospitals, which had the highest

ing, was also noted by physicians in other mained undecided [23]. Taken into con- scores regarding the perceived ‘usefulness

surveys [13, 31]. Furthermore, we found a sideration the relatively low positive pre- of the alerts’, have already taken preventive

broad consensus by the clinicians over the dictive value of alerts, mandatory docu- action precisely on this issue. Their more

issue of increased patient and medication mentation of override reasons appears to strategic alerting strategies sought not to

safety through the use of CPOE/CDS in potentially increase alert fatigue [39]. How- patronize the physicians, but use sophisti-

our study and also in other surveys [25 –27, ever, it remains unclear whether or not the cated presentations to prevent alert fatigue.

30]. A few physicians in our survey men- physicians should be obliged to enter rea- It might be that the alerting strategy and

tioned technology reliance as possible sons when overriding serious drug-interac- the way the information is presented to the

negative effects. This concern was shared tion alerts [23, 28]. physician play a major role in their general

by Holde et al. [27]. Other surveys found The physicians in our survey stated that attitude towards alerting in CPOE. This

that physicians felt that automatic alerting there should be a greater distinction be- theory is supported by a systematic review

had an influence on their initial prescribing tween important and less important alerts. by Langemeijer et al., which revealed that

decisions [23], which would, however, not This is supported by other studies [28, 29, the physicians preferred alert designs

limit the professional autonomy of the pre- 37]. The physicians in our survey express a which distinguished between the severity

scriber [22]. Our quantitative results sup- need for specific alerts adapted to the clini- levels [50].

port these findings. cal context, which was suggested by other

The danger of an annoying overload of researchers as well [13, 31, 43, 44]. An ap-

irrelevant alerts as reported by the physi- proach that considers the clinical context in

Methods Inf Med 2/2013 © Schattauer 2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

M. Jung et al.: Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems 107

The research leading to these results has re- 14. Ash JS, Sittig DF, Dykstra RH, et al. Categorizing

10. Unanswered and New the unintended sociotechnical consequences of

ceived funding from the European Com-

Questions munity’s Seventh Framework Programme

computerized provider order entry. Int J Med In-

form 2007; 76 (Suppl 1): S21–27.

Our study was not designed to reveal and (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement 15. Ammenwerth E, Talmon J, Ash JS, et al. Impact of

quantify the factors that may explain sig- no. 216130. CPOE on mortality rates--contradictory findings,

important messages. Methods Inf Med 2006; 45

nificant differences in the attitude of physi- (6): 586–593.

cians towards CPOE and alerting. Our re- 16. Ash JS, Stavri PZ, Dykstra R, et al. Implementing

sults indicate that basic beliefs may have a References computerized physician order entry: the import-

stronger influence than the practical ex- ance of special people. Int J Med Inform 2003; 69

1. Institute of Medicine. Preventing Medication Er- (2–3): 235–250.

perience with CPOE, and that hospitals rors: Quality Chasm Series. Aspden P, Wolcott J, 17. Ash JS, Sittig DF, Poon EG, et al. The extent and

with a sophisticated alerting strategy with Bootman J, editors. Washington DC: National importance of unintended consequences related to

less interruptive alerts tend towards more Academy Press; 2006. computerized provider order entry. J Am Med

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Inform Assoc 2007; 14 (4): 415–423.

positive attitudes. Altogether, this should Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washing- 18. Georgiou A, Lang S, Alvaro F, et al. Pathology’s

be further investigated by experiment in ton DC: National Academic Press; 2000. front line – a comparison of the experiences of

future studies, probably including even 3. White SV. Patient Safety Issues. In: Byers JF, White electronic ordering in the clinical chemistry and

more hospitals. SV, editors. Patient Safety: Principles and Practice. haematology departments. Stud Health Technol

New York: Springer; 2004. Inform 2007; 130: 121–132.

4. Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of 19. Saathoff A. Human factors considerations relevant

adverse drug events and potential adverse drug to CPOE implementations. J Healthc Inf Manag

11. Conclusions events. Implications for prevention. ADE Preven-

tion Study Group. JAMA 1995; 274 (1): 29–34.

2005; 19 (3): 71–78.

20. Snyder R, Weston MJ, Fields W, et al. Computer-

5. Benkirane RR, Abouqal R, Haimeur CC, et al. ized provider order entry system field research: the

In this survey, we tried to measure the atti- Incidence of adverse drug events and medication impact of contextual factors on study implemen-

tude towards automatic alerting in CPOE errors in intensive care units: a prospective multi- tation. Int J Med Inform 2006; 75 (10–11):

systems in various settings. The general at- center study. J Patient Saf. 2009; 5 (1): 16–22. 730–740.

6. Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Machan C, et 21. Wentzer HS, Bottger U, Boye N. Unintended

titude of the physicians is positive, inde-

al. The effect of electronic prescribing on medi- transformations of clinical relations with a com-

pendently of the country, the organiza- cation errors and adverse drug events: a systematic puterized physician order entry system. Int J Med

tional setting and the personal CPOE ex- review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008; 15 (5): Inform 2007; 76 (Suppl 3): S456–461.

perience. A well-developed alerting strat- 585–600. 22. Hor CP, O’Donnell JM, Murphy AW, et al. General

7. Kaushal R, Bates DW. Making Health Care Safer: practitioners’ attitudes and preparedness towards

egy seems to positively influence the physi- A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Clinical Decision Support in e-Prescribing (CDS-

cians’ attitudes. To achieve this, highly Chapter 6: Computerized Physician Order Entry eP) adoption in the West of Ireland: a cross sec-

structured drug and patient case informa- (CPOE) with Clinical Decision Support Systems tional study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010;

tion is needed, as well as locally customiz- (CDSSs). Evidence Report/Technology Assess- 10: 2.

ment. Rockville: U.S. Department of Health and 23. Ko Y, Abarca J, Malone DC, et al. Practitioners’

able CPOE systems which are capable of Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research views on computerized drug-drug interaction

taking into account the clinical context and and Quality AHRQ;2001 Jul 20. Report No.: 43 alerts in the VA system. J Am Med Inform Assoc

of differently presenting the alert informa- Contract No.: 290–97–0013. 2007; 14 (1): 56–64.

tion to the user. 8. Bonnabry P, Despont-Gros C, Grauser D, et al. A 24. Magnus D, Rodgers S, Avery AJ. GPs’ views on

risk analysis method to evaluate the impact of a computerized drug interaction alerts: question-

computerized provider order entry system on pa- naire survey. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002; 27 (5):

tient safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008; 15 (4): 377–382.

Acknowledgments 453–460. 25. Allenet B, Bedouch P, Bourget S, et al. Physicians’

We gratefully acknowledge the help of the 9. Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role of com- perception of CPOE implementation. Int J Clin

puterized physician order entry systems in facili- Pharm 2011; 33 (4): 656–664.

following persons who helped to translate tating medication errors. JAMA 2005; 293 (10): 26. Khajouei R, Wierenga PC, Hasman A, et al. Clini-

the questionnaires and made valuable con- 1197–1203. cians satisfaction with CPOE ease of use and effect

tributions to the organization of the sur- 10. Han YY, Carcillo JA, Venkataraman ST, et al. Un- on clinicians’ workflow, efficiency and medication

veys in the local hospitals: Maurice Lange- expected increased mortality after implementation safety. Int J Med Inform. 2011; 80 (5): 297–309.

of a commercially sold computerized physician 27. Holden RJ. Physicians’ beliefs about using EMR

meijer (Amsterdam); Karin Kopitowksi order entry system. Pediatrics. 2005; 116 (6): and CPOE: in pursuit of a contextualized under-

(Buenos Aires); Jens Barholdy, Kaspar Cort 1506–1512. standing of health IT use behavior. Int J Med In-

Madsen, Flemming Steen Nielsen, Lars 11. Campbell EM, Sittig DF, Ash JS, et al. Types of un- form 2010; 79 (2): 71–80.

intended consequences related to computerized 28. Yu KH, Sweidan M, Williamson M, et al. Drug in-

Nygård, Jesper Vilandt, Morten Wøjde- provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc teraction alerts in software--what do general prac-

mann (Copenhagen); Philippe Lecocq 2006; 13 (5): 547–556. titioners and pharmacists want? Med J Aust 2011;

(Denain); Jakob Krösslhuber, Kathrin Radl 12. Sittig DF, Krall M, Kaalaas-Sittig J, et al. Emotional 195 (11–12): 676–680.

(Feldkirch); Jean Doucet (Rouen); Kras- aspects of computer-based provider order entry: a 29. Ahearn MD, Kerr SJ. General practitioners’ per-

qualitative study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005; 12 ceptions of the pharmaceutical decision-support

simira Nechkova, Dimitar Tcharaktchiev (5): 561–567. tools in their prescribing software. Med J Aust

(Sofia); Maria Farini (Thessaloniki). We 13. Khajouei R, Jaspers MW. The impact of CPOE 2003; 179 (1): 34–37.

would also like to thank all of those who medication systems’ design aspects on usability, 30. Weingart SN, Simchowitz B, Shiman L, et al. Clini-

volunteered in pre-testing the question- workflow and medication orders: a systematic re- cians’ assessments of electronic medication safety

view. Methods Inf Med 2010; 49 (1): 3–19.

naires.

© Schattauer 2013 Methods Inf Med 2/2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

108 M. Jung et al.: Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems

alerts in ambulatory care. Arch Intern Med 2009; 37. Taylor LK, Tamblyn R. Reasons for physician non- 44. van der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of

169 (17): 1627–1632. adherence to electronic drug alerts. Stud Health drug safety alerts in computerized physician order

31. Sittig DF, Krall MA, Dykstra RH, et al. A survey of Technol Inform 2004; 107 (Pt 2): 1101–1105. entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006; 13 (2):

factors affecting clinician acceptance of clinical 38. Feldstein A, Simon SR, Schneider J, et al. How to 138–147.

decision support. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak design computerized alerts to safe prescribing 45. Riedmann D, Jung M, Hackl WO, et al. Develop-

2006; 6: 6. practices. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2004; 30 (11): ment of a context model to prioritize drug safety

32. Kuperman GJ, Bobb A, Payne TH, et al. Medi- 602–613. alerts in CPOE systems. BMC Med Inform Decis

cation-related clinical decision support in com- 39. Eppenga WL, Derijks HJ, Conemans JM, et al. Mak 2011; 11 (1): 35.

puterized provider order entry systems: a review. J Comparison of a basic and an advanced pharma- 46. Riedmann D, Jung M, Hackl WO, et al. How to im-

Am Med Inform Assoc 2007; 14 (1): 29–40. cotherapy-related clinical decision support system prove the delivery of medication alerts within

33. Mayring P. Qualitative Content Analysis. FQS: in a hospital care setting in the Netherlands. J Am computerized physician order entry systems: an

Qualitative Methods in Various Disciplines I: Med Inform Assoc 2012; 19 (1): 66–71. international Delphi study. J Am Med Inform

Psychology [serial on the Internet]. 2000 [cited 40. Imhoff M, Kuhls S. Alarm algorithms in critical Assoc 2011.

2011 Aug 3]; 1(2): Available from: http://www. care monitoring. Anesth Analg. 2006; 102 (5): 47. Wipfli R, Lovis C. Alerts in clinical information

qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/ 1525–1537. systems: building frameworks and prototypes.

view/1089/2385. 41. Lawless ST. Crying wolf: false alarms in a pediatric Stud Health Technol Inform 2010; 155: 163–169.

34. Oertle M. Frequency and nature of drug-drug in- intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1994; 22 (6): 48. van der Sijs H, van Gelder T, Vulto A, et al. Under-

teractions in a Swiss primary and secondary acute 981–985. standing handling of drug safety alerts: a simu-

care hospital. Swiss Med Wkly 2012; 142: 0. 42. Jaspers MW, Smeulers M, Vermeulen H, et al. Ef- lation study. Int J Med Inform 2010; 79 (5):

35. Borbolla D, Otero C, Lobach DF, et al. Implemen- fects of clinical decision-support systems on prac- 361–369.

tation of a clinical decision support system using a titioner performance and patient outcomes: a syn- 49. Kirchner M, Burkle T, Patapovas A, et al. Building

service model: results of a feasibility study. Stud thesis of high-quality systematic review findings. J the technical infrastructure to support a study on

Health Technol Inform. 2010; 160 (Pt 2): 816–820. Am Med Inform Assoc 2011; 18 (3): 327–334. drug safety in a general hospital. Stud Health Tech-

36. Glassman PA, Simon B, Belperio P, et al. Improv- 43. Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, Wang S, et al. Ten com- nol Inform 2011; 169: 325–329.

ing recognition of drug interactions: benefits and mandments for effective clinical decision support: 50. Langemeijer MM, Peute LW, Jaspers MW. Impact

barriers to using automated drug alerts. Med Care making the practice of evidence-based medicine a of alert specifications on clinicians’ adherence.

2002; 40 (12): 1161–1171. reality. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2003; 10 (6): Stud Health Technol Inform 2011; 169: 930–934.

523–530.

Methods Inf Med 2/2013 © Schattauer 2013

Downloaded from www.methods-online.com on 2018-01-01 | IP: 36.79.131.171

For personal or educational use only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Reflecting on UPHSD's Mission, Vision, and Core ValuesDocument3 pagesReflecting on UPHSD's Mission, Vision, and Core ValuesBia N Cz100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Shop SupervisionDocument38 pagesShop SupervisionSakura Yuno Gozai80% (5)

- 051 Clinical Decision Support For Atypical OrdersDocument6 pages051 Clinical Decision Support For Atypical OrdersRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- To The PointDocument10 pagesTo The PointRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Policy Development 4Document114 pagesHealth Policy Development 4Rudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- 317 Value of Pharmacist Medication Interviews On Optimizing The Electronic Medication Reconciliation ProcessDocument1 page317 Value of Pharmacist Medication Interviews On Optimizing The Electronic Medication Reconciliation ProcessRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of An Electronic Medication Reconciliation Application and Process Redesign On Potential Adverse Drug EventsDocument10 pagesEffect of An Electronic Medication Reconciliation Application and Process Redesign On Potential Adverse Drug EventsRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Prescriber Response To Computerized Drug Alerts For Electronic PrescriptionsDocument6 pagesPrescriber Response To Computerized Drug Alerts For Electronic PrescriptionsRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Thrall 2014Document5 pagesThrall 2014Rudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Combing Signals From Spontaneous Reports and Electronic Health Records For Detection of Adverse Drug ReactionsDocument7 pagesCombing Signals From Spontaneous Reports and Electronic Health Records For Detection of Adverse Drug ReactionsRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- A Collaborative Approach To DevelopingDocument11 pagesA Collaborative Approach To DevelopingRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Computerized Provider Order Entry With Clinical Decision Support On Adverse Drug Events in The Long-Term Care SettingDocument9 pagesEffect of Computerized Provider Order Entry With Clinical Decision Support On Adverse Drug Events in The Long-Term Care SettingRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Automatic Errors A Case Series On The Errors Inherent in Electronic PrescribingDocument4 pagesAutomatic Errors A Case Series On The Errors Inherent in Electronic PrescribingRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Designing Information Technology To Support Prescribing Decision MakingDocument6 pagesDesigning Information Technology To Support Prescribing Decision MakingRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Krueger On Focus Group InterviewDocument18 pagesKrueger On Focus Group InterviewArnab Guha MallikPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Steps To Conducting A Systematic ReviewDocument4 pages5 Steps To Conducting A Systematic ReviewJoanna BennettPas encore d'évaluation

- Ipi 508427Document6 pagesIpi 508427Alvi ChristantoPas encore d'évaluation

- ADEpedia 2.0 Integration of Normalized Adverse Drug Events (ADEs)Document5 pagesADEpedia 2.0 Integration of Normalized Adverse Drug Events (ADEs)Rudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Considerations For A Successful Clinical Decision Support SystemDocument8 pagesConsiderations For A Successful Clinical Decision Support SystemRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Computerised Physician Order Entry-Related Medication Errors Analysis of Reported Errors and Vulnerability Testing of Current SystemsDocument9 pagesComputerised Physician Order Entry-Related Medication Errors Analysis of Reported Errors and Vulnerability Testing of Current SystemsRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison of Documentation of Patient Reported Adverse Drug Reactions On Both Paper-Based Medication Charts and Electronic Medication Charts at A New Zealand HospitalDocument7 pagesComparison of Documentation of Patient Reported Adverse Drug Reactions On Both Paper-Based Medication Charts and Electronic Medication Charts at A New Zealand HospitalRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison of Two Knowledge Bases On The Detection of Drug-Drug Interactions.Document5 pagesComparison of Two Knowledge Bases On The Detection of Drug-Drug Interactions.Rudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Steps To Conducting A Systematic ReviewDocument4 pages5 Steps To Conducting A Systematic ReviewJoanna BennettPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Evaluation of Three Clinical Decision SupportDocument11 pagesComparative Evaluation of Three Clinical Decision SupportRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Jamia: The Practice ofDocument16 pagesJamia: The Practice ofRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Protocol - Allergen Injection Immunotherapy For Perennial AllDocument10 pagesProtocol - Allergen Injection Immunotherapy For Perennial AllRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Jamia: The Practice ofDocument16 pagesJamia: The Practice ofRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- DKI Wound Related Allergic Irritant Contact Dermatitis.8Document9 pagesDKI Wound Related Allergic Irritant Contact Dermatitis.8Rudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Male Non-Gonococcal Urethritis: From Microbiological Etiologies To Demographic and Clinical FeaturesDocument7 pagesMale Non-Gonococcal Urethritis: From Microbiological Etiologies To Demographic and Clinical FeaturesRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- A Brief Historical Overview of Hospital Information System EvolutionDocument21 pagesA Brief Historical Overview of Hospital Information System EvolutionRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Protocol - Allergen Injection Immunotherapy For Perennial AllDocument10 pagesProtocol - Allergen Injection Immunotherapy For Perennial AllRudi IlhamsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Siart, Et. Al (2018) Digital GeoarchaeologyDocument272 pagesSiart, Et. Al (2018) Digital GeoarchaeologyPepe100% (2)

- Unit 3.1 - Hydrostatic ForcesDocument29 pagesUnit 3.1 - Hydrostatic ForcesIshmael MvunyiswaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dball-Gm5 en Ig Cp20110328aDocument18 pagesDball-Gm5 en Ig Cp20110328aMichael MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Maths Note P1 and P3Document188 pagesMaths Note P1 and P3Afeefa SaadatPas encore d'évaluation

- The Influence of Teleworking On Performance and Employees Counterproductive BehaviourDocument20 pagesThe Influence of Teleworking On Performance and Employees Counterproductive BehaviourCHIZELUPas encore d'évaluation

- Small Healthcare Organization: National Accreditation Board For Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (Nabh)Document20 pagesSmall Healthcare Organization: National Accreditation Board For Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (Nabh)Dipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Company Profile HighlightsDocument7 pagesCompany Profile HighlightsRaynald HendartoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Critical Need For Software Engineering EducationDocument5 pagesThe Critical Need For Software Engineering EducationGaurang TandonPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab Report 1Document8 pagesLab Report 1Hammad SattiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Eukaryotic Replication Machine: D. Zhang, M. O'DonnellDocument39 pagesThe Eukaryotic Replication Machine: D. Zhang, M. O'DonnellÁgnes TóthPas encore d'évaluation

- CHB1 Assignmen5Document2 pagesCHB1 Assignmen5anhspidermenPas encore d'évaluation

- DrdoDocument2 pagesDrdoAvneet SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Sinavy Pem Fuel CellDocument12 pagesSinavy Pem Fuel CellArielDanieli100% (1)

- Influence of Oxygen in Copper - 2010Document1 pageInfluence of Oxygen in Copper - 2010brunoPas encore d'évaluation

- CLOZE TEST Fully Revised For SSC, Bank Exams & Other CompetitiveDocument57 pagesCLOZE TEST Fully Revised For SSC, Bank Exams & Other CompetitiveSreenu Raju100% (2)

- 123 The Roots of International Law and The Teachings of Francisco de Vitoria As A FounDocument23 pages123 The Roots of International Law and The Teachings of Francisco de Vitoria As A FounAki LacanlalayPas encore d'évaluation

- Workflowy - 2. Using Tags For NavigationDocument10 pagesWorkflowy - 2. Using Tags For NavigationSteveLangPas encore d'évaluation

- An Introduction To Community DevelopmentDocument21 pagesAn Introduction To Community DevelopmentThuyAnh NgnPas encore d'évaluation

- ECE Laws and Ethics NotesDocument29 pagesECE Laws and Ethics Notesmars100% (1)

- Materials Technical Specification.: Stainless SteelDocument6 pagesMaterials Technical Specification.: Stainless SteelMario TirabassiPas encore d'évaluation

- Internal Controls and Risk Management: Learning ObjectivesDocument24 pagesInternal Controls and Risk Management: Learning ObjectivesRamil SagubanPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Mesl StudoDocument15 pagesBest Mesl StudoJoenielPas encore d'évaluation

- READING 4.1 - Language and The Perception of Space, Motion, and TimeDocument10 pagesREADING 4.1 - Language and The Perception of Space, Motion, and TimeBan MaiPas encore d'évaluation

- REFLEKSI KASUS PLASENTADocument48 pagesREFLEKSI KASUS PLASENTAImelda AritonangPas encore d'évaluation

- DANA 6800-1 Parts ManualDocument4 pagesDANA 6800-1 Parts ManualDude manPas encore d'évaluation

- HWXX 6516DS1 VTM PDFDocument1 pageHWXX 6516DS1 VTM PDFDmitriiSpiridonovPas encore d'évaluation

- E Requisition SystemDocument8 pagesE Requisition SystemWaNi AbidPas encore d'évaluation

- Calibration Method For Misaligned Catadioptric CameraDocument8 pagesCalibration Method For Misaligned Catadioptric CameraHapsari DeviPas encore d'évaluation