Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Guide To Understanding Mdi 2016

Transféré par

Nuraini AhmadTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Guide To Understanding Mdi 2016

Transféré par

Nuraini AhmadDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

MDI

GUIDE

2015/2016 THE MIDDLE YEARS DEVELOPMENT INSTRUMENT

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING

YOUR MDI RESULTS

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 1

The MDI team would like to extend its warmest appreciation to the students,

teachers, and administrators who made this project possible. Thank you for your

participation.

MDI research is made possible with funding from the United Way of the Lower

Mainland (UWLM) and school districts across BC. We would like to thank and

acknowledge the UWLM and all participating school districts for their support and

collaboration on this project.

HELP’s middle years research is led by Dr. Kimberly Schonert-Reichl. HELP

acknowledges Dr. Schonert-Reichl for her leadership in social and emotional

development research, her dedication to exploring children’s experiences in the

middle years and for raising the profile of children’s voices, locally and internationally.

HELP faculty and staff also would like to acknowledge our Founding Director, Dr. Clyde

Hertzman, whose life’s work is a legacy for the institute’s research. He continues

to inspire and guide our work and will always be celebrated as ‘a mentor to all who

walked with him.’

For more information please contact HELP’s MDI Project Coordinator:

Email: mdi@help.ubc.ca

Website: earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi

Suggested citation

Human Early Learning Partnership. The Middle Years Development Instrument: A Guide to

Understanding Your MDI Results. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, School of

Population and Public Health; May 2016.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

ABOUT THIS GUIDE 4

WHY THE MIDDLE YEARS MATTER 4

WHY CHILDREN’S VOICES? 4

ABOUT THE MDI 5

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE MDI 6

MDI DATA COLLECTION 6

VALIDITY OF RESULTS 6

PRIVACY AND DATA SUPPRESSION 7

HOW ARE MDI RESULTS REPORTED? 7

NEIGHBOURHOOD BOUNDARIES 7

Dimensions of the MDI 8

SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 9

PHYSICAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING 13

CONNECTEDNESS 15

USE OF AFTER-SCHOOL TIME 18

SCHOOL EXPERIENCES 22

The Well-being and Assets Indices 24

THE WELL-BEING INDEX 25

THE ASSETS INDEX 26

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ASSETS AND WELL-BEING 27

Moving to Action with your MDI Results 28

Related References and Research 30

Additional Resources 34

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 3

INTRODUCTION

ABOUT THIS GUIDE

The MDI companion, “A Guide to Understanding your MDI Results” was developed to support the interpretation and application of

MDI results for schools and communities. The guide provides:

• Information on the MDI survey questions, response scales and scoring methods for each dimension and measure;

• Answers to important questions related to data collection and privacy, mapping and reporting, as well as the reliability

and validity of the MDI;

• Recommendations for moving to action with your MDI results;

• Highlights from current research related to children’s healthy development during the middle years and evidence on the

importance of the MDI’s five dimensions of children’s well-being; and,

• Related research publications and online resources.

WHY THE MIDDLE YEARS MATTER

Middle childhood, from ages 6 to 12, marks a distinct period in human development. During this time, children experience

important cognitive, social and emotional changes that establish their lifelong identity and set the stage for adolescence and

adulthood. Research shows that a child’s overall health and well-being during this critical period of development affects their ability

to concentrate and learn, develop and maintain friendships, and make thoughtful decisions.

As children transition through elementary and middle school it is common to observe declines in children’s self-reported

confidence, self-concept, optimism, empathy, satisfaction with life and social responsibility. However, these declines are not

inevitable and while middle childhood is a time of risk, it is also a time of opportunity. There is mounting evidence to suggest

children’s positive connections to a parent, peer, or adult in the community results in greater empathy towards others, higher

optimism, and higher self-esteem.

The purpose of the Human Early Learning Partnership’s (HELP) middle years research is to gain a deeper understanding of how

populations of children are doing at this stage in their lives. Children’s perspectives on their experiences both inside and outside of

school provides us with important information to support evidence-based decisions on funding allocation, program delivery and

policy. The results also highlight our shared roles and responsibilities in supporting children’s health and well-being through their

environments, relationships and experiences.

WHY CHILDREN’S VOICES?

The MDI upholds Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which emphasizes the importance of

children’s voices: ‘When adults are making decisions that affect children, children have a right to say what they think should

happen and have their opinions taken into account.” (United Nations, 1989).

The MDI is a unique tool that allows children’s voices to be heard. It gives us insight into areas that have great significance in

children’s lives but are not typically evaluated by other assessment tools. Rather than evaluating academic progress, the MDI gives

children an opportunity to communicate their experiences, feelings and wishes. See “Validity of Results” section of this report for

more information on the validity and reliability of children’s self-report assessments.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 4

INTRODUCTION

ABOUT THE MDI

The Middle Years Development Instrument (MDI) is a self-report questionnaire

that goes beyond academics by asking children in grades 4 and 7 about their

thoughts, feelings and experiences in school and in the community. The MDI is not

12yrs an assessment for individual children. Instead, it is a unique and comprehensive

population-based measure that helps us gain a deeper understanding of children’s

health and well-being during middle childhood.

9yrs The MDI uses a strengths-based approach to assess five dimensions of development

that are strongly linked to well-being, health, academic achievement and success

throughout the school years and in later life.

The 5 Dimensions of the MDI

Social and Emotional Development: Optimism, empathy, happiness, prosocial

behaviour, self-esteem.

Physical Health and Well-being: General health, body image, nutrition,

sleeping patterns.

Connectedness: Presence of supportive adults, sense of belonging with peers.

Additional reading on the

development of the MDI: School Experiences: Academic self-concept, school climate, bullying.

Schonert-Reichl, K. (2011). Middle

Use of After-School Time: Time spent engaged in organized activities,

childhood inside and out: The psychological

lessons, watching TV, playing video games, socializing with friends.

and social worlds of Canadian children ages

9-12, Full Report. Report for the United

Way of the Lower Mainland. Vancouver: Each of these dimensions is made up of several measures and each measure is made

University of British Columbia. up of one or more questions. The Grade 4 version of the MDI contains 77 questions,

while the Grade 7 MDI has 101 questions.

Available online at

earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi. Most questions ask children to rate their agreement with a series of statements.

For example; “I start most days thinking I will have a good day.” 1) Disagree a lot,

2) Disagree a little, 3) Don’t agree or disagree, 4) Agree a little, or 5) Agree a lot.

The MDI emphasizes the protective factors and assets in a child’s life that are known

to support and optimize development. MDI results provide educators, parents,

researchers, community organizations, and policy makers with information about the

psychological and social worlds of children during middle childhood. As a population

measure the MDI allows us to see trends and patterns in how populations of children

in middle years are doing over time. By reviewing and sharing MDI results, the

opinions and concerns of children are validated and decision-makers are better

prepared to move toward actions that will create supportive environments where

children can thrive.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 5

INTRODUCTION

Additional reading on the validity A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE MDI

of children’s self-report:

In 2009, the Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP) at the University of British

Columbia (UBC), in partnership with the United Way of the Lower Mainland,

Schonert-Reichl, K., Guhn, M., developed a tool to gather information about the lives of children in Grade 4: The

Gadermann, A., Hymel, S., Sweiss, L., & Middle Years Development Instrument (MDI). The survey items were selected by

Hertzman, C. (2013). Development and children, parents and educators and were tested rigorously to ensure the survey

validation of the Middle Years Development produced data of sound reliability and validity.

Instrument (MDI): Assessing children’s well- Since its first implementation with Grade 4 students in Vancouver in 2009, the MDI

being and assets across multiple contexts. has expanded rapidly across British Columbia. The questionnaire has been completed

Social Indicators Research, 114(2): 345-369. by over 23,000 Grade 4 students across the province. The Grade 7 survey was first

implemented in 2012-13 and since then has been completed by over 9,000 students.

Varni, J. , Limbers, C. , & Burwinkle, T.

(2007). How young can children reliably MDI DATA COLLECTION

and validly self-report their health-related Participation in the MDI is voluntary. Participating schools send information letters

quality of life?: An analysis of 8,591 children home with students. Parents may withdraw their children at any time and children

across age subgroups with the PedsQL™ 4.0 also have the option to decline participation. Data collection is currently conducted

Generic Core Scales. Health and Quality of in public schools. Students complete the MDI during class time, under teacher or

Life Outcomes, 5(1): 1-13. principal supervision, during the month of November.

VALIDITY OF RESULTS

Previous research has found that responses from children in Grade 4 and above are

as reliable and valid as responses from adults. A total of four studies were conducted

to test the validity of the MDI survey, including two initial pilots in 2008, and two

district-wide pilots in both urban and rural communities in 2009 and 2010. Results

from these studies showed the MDI to have both strong reliability and validity. Data

checks are repeated every year to ensure the data collected each year meets rigorous

research standards.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 6

INTRODUCTION

PRIVACY AND DATA SUPRESSION

The protection of children’s privacy is a key consideration for researchers and staff

working with MDI data. The systems and processes used to collect, store and report

on MDI data, meet or exceed the requirements of provincial and federal privacy

legislation. Names and addresses of children are not collected. Some identifier

data, such as postal codes and dates of birth, are used to assist with analysis and

reporting. Identifiable information is removed before records are encrypted and stored

in a highly secure data storage facility at the University of British Columbia. Where

neighbourhoods or districts contain fewer than 35 children the results are suppressed

to ensure that individual children cannot be identified.

HOW ARE MDI RESULTS REPORTED?

MDI

GRADE 4

Data collected from the MDI questionnaires are reported at three different levels of

geography: school, neighbourhood and school district.

School Reports – Contain data specific to the population of children who participated

in the MDI at an individual school. These reports are internal and are not released

SCHOOL DISTRICT 8 KOOTENAY LAKE

publicly. School reports can be shared with teachers, parents and community partners

SCHOOL DISTRICT

MDIREPORT

& COMMUNITY at the discretion of the school district administration.

GRADE 7

School District and Community Reports - Contain data representing all of the children

who were surveyed within a school district. Data are aggregated and averages are

reported at both the school district and the neighbourhood levels:

2015/16 GRADE 4 RESULTS

• School district data - Averages are reported for all children who participated

SCHOOL DISTRICT 8 KOOTENAY LAKE

SCHOOL DISTRICT within the geographic school district boundary.

& COMMUNITY REPORT

• Neighbourhood data - Averages are reported for all children living within a

particular neighbourhood. These data are aggregated using children’s home

postal codes, not by where they attend school.

School District and Community Reports are made publicly available at

2015/16 GRADE 7 RESULTS

132 Ave

128 Ave www.earlylearning.ubc.ca/maps/mdi/nh.

224 St

203 St

Dewdney Trunk Rd

NEIGHBOURHOOD BOUNDARIES

Ha

ne

yB

yp

240 St

ass

St

n

W ilso

ey

K

s

ne

to

Neighbourhood boundaries were defined in close consultation with community

Av

e

104 Ave St

St

287

Stave Lake

Walnut Walnut

96 Ave Grove West Grove East -

Fort Langley stakeholders. HELP consults with community contacts and works collaboratively to

200 St

88 Ave

adjust geographical boundaries as needed. MDI maps and reports are continuously

Rd

revised to reflect such changes.

r

ve

80 Ave

G lo

Willoughby Abbot

In order to provide consistency between MDI data and census data, boundaries

Hig sfo

72 Ave hw rd

ay 10

Mis

sio

n

have typically been drawn to align, where possible, with municipal planning areas

Hw y

64 Ave

¥ 1 58 Ave Harris Rd

Langley

and to coincide with census and taxfiler data. In most cases, boundaries are also set

Mount Le hm

56 Ave

Gladwin Rd

Bradner Rd

City North 52 Ave

Langley

Murrayville Rural Langley to neighbourhoods with a minimum number of 50 children. These considerations

an Rd

City Downes Rd

South

have reduced the number of neighbourhoods where data are suppressed due to low

192 St

184 St

Fra

168 St

208 St

ser

Hwy

Maclure Rd

numbers of children, while at the same time ensuring accuracy and precision of MDI

O

36 Ave

ld

Y ale Rd

216 St

232 St

32 Ave Aldergrove South Fraser Way

Brookswood - Fernridge data.

264 St

272 St

176 St

Marshall Rd

24 Ave

Mccallum R d

An interactive map of neighbourhood boundaries, complete with street names, can be

King Rd

Clearbrook Rd

16 Ave

found at: www.earlylearning.ubc.ca/maps/interactive.

Huntingdon Rd

8 Ave

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 7

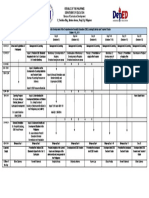

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI

The MDI uses a strengths-based approach to assess five areas of development that are strongly linked to

children’s well-being, health and academic achievement. It focuses on highlighting the protective factors

and assets that are known to support and optimize development in middle childhood. These areas are:

Social and Emotional Development, Physical Health and Well-Being, Connectedness, Use of After-School

Time and School Experiences. Each of these dimensions is made up of several measures and each measure

is made up of one or more questions. The chart below illustrates the relationship between MDI dimensions

and measures, and highlights which measures contribute to the Well-Being and Assets Indices.

5 DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI

SOCIAL & EMOTIONAL PHYSICAL HEALTH & CONNECTEDNESS USE OF SCHOOL

DEVELOPMENT WELL-BEING AFTER-SCHOOL TIME EXPERIENCES

MEASURES MEASURES MEASURES MEASURES MEASURES

Optimism General Health Adults at School Organized Activities Academic Self-Concept

Empathy Eating Breakfast Adults in the - Educational Lessons School Climate

Prosocial Behaviour Meals with Neighbourhood or Activities School Belonging

Self-Esteem Adults at Home Adults at Home - Youth Organizations Motivation

Happiness Frequency of Peer Belonging - Sports Future Goals

Absence of Sadness Good Sleep Friendship Intimacy - Music or Arts Victimization and

Absence of Worries Body Image Important Adults How Children Spend Bullying

Self-Regulation Their Time

(Short & Long Term) After-School People

*Responsible and Places

Decision-Making Children's Wishes and

*Self-Awareness Barriers

*Perseverance

*Assertiveness

*Citizenship and Social

Responsibility

* Grade 7 only

WELL-BEING INDEX ASSETS INDEX

A measure in the Well-Being Index A measure in the Assets Index

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 8

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

SOCIAL AND Social and emotional well-being is critical for children’s successful development

EMOTIONAL across the life span. When children are able to understand and manage their emotions

they are better able to show empathy and maintain positive relationships. Social and

DEVELOPMENT

emotional well-being is associated with greater motivation and success in school, as

well as positive outcomes later in life: post-secondary education, employment, healthy

Response Options lifestyles and psychological well-being.

The MDI asks children to respond to questions about their current social and

Agree a lot

emotional functioning in the following areas: optimism, empathy, prosocial behaviour,

Agree a little self-esteem, happiness, self-regulation and psychological well-being. In addition, the

Don’t agree or disagree Grade 7 questionnaire asks about the following: responsible decision-making, self-

Disagree a little awareness, perseverance and assertiveness.

Disagree a lot

OPTIMISM. Optimism refers to the mindset of having positive expectations for the

Scoring

future. Optimism predicts a range of long-term benefits including greater success

in school and work, less likelihood of depression and anxiety, greater satisfaction

High: Children whose average

in relationships, better physical health and longer life. It is also a strong predictor

responses were ‘Agree a little’

of resiliency for children facing adversity. Children are asked to rate the following

or ‘Agree a lot’

statements:

Medium: Children whose

• I have more good times than bad times.

average responses were ‘Don’t

agree or disagree’ or those • I believe more good things than bad things will happen to me.

who reported a mix of positive

and negative responses • I start most days thinking I will have a good day.

Low: Children whose average

responses were ‘Disagree a EMPATHY. Empathy is the experience of feeling what another person feels. Research

little’ or ‘Disagree a lot’ shows empathic children are better able to foresee the negative social consequences

of their actions and are better able to problem-solve during challenging situations.

Example Result Children are asked to rate the following statements:

0% 25% 50% 75% 100% • I am a person who cares about the feelings of others.

%

61% • I feel sorry for other kids who don’t have the things that I have.

%

28% • When I see someone being mean it bothers me.

12%

%

Average for all participating PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOUR. Prosocial behaviour is behaving in socially appropriate and

school districts. responsible ways. Not only are prosocial skills valued by teachers, they may also

protect against bullying from peers. Prosocial children demonstrate greater empathic

awareness than either bullies or children targeted by bullies. Children are asked to rate

the following statements:

Response Options

for Prosocial Behaviour questions • I helped someone who was hurt.

Many times a week

• I helped someone who was being picked on.

About every week

About every month • I cheered someone up who was feeling sad.

Once or a few times

Not at all this school year

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 9

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

SELF-ESTEEM. Self-esteem refers to a person’s sense of self-worth. It is one of the

Response Options most critical measures of middle childhood health and well-being. It is during the

middle childhood years that children begin to form beliefs about themselves as either

Agree a lot “competent” or “inferior” people. Children are asked to rate the following statements:

Agree a little • A lot of things about me are good.

Don’t agree or disagree • In general, I like being the way I am.

Disagree a little

• Overall, I have a lot to be proud of.

Disagree a lot

Scoring HAPPINESS. Happiness, or subjective well-being, refers to how content or satisfied

children are with their lives. Happiness serves a greater advantage than just feeling

High: Children whose average good: children with a positive, friendly attitude are more likely to attract positive

responses were ‘Agree a little’ attention from peers and adults, thus broadening and strengthening their social

or ‘Agree a lot’ resources. Experiencing happiness also strengthens children’s coping resources when

Medium: Children whose negative experiences occur. Children are asked to rate the following statements:

average responses were ‘Don’t • In most ways my life is close to the way I would want it to be.

agree or disagree’ or those

who reported a mix of positive • The things in my life are excellent.

and negative responses

• I am happy with my life.

Low: Children whose average

responses were ‘Disagree a • So far I have gotten the important things I want in life.

little’ or ‘Disagree a lot’

• If I could live my life over, I would have it the same way.

Example Result

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

ABSENCE OF SADNESS. Depression is estimated to affect 1 in every 15 children in

%

78% Canada. It has a later onset than anxiety, usually beginning around the time of

puberty. Depression affects children’s ability to concentrate and also limits their ability

%

16%

to experience enjoyment or pleasure in things. Depressive symptoms during middle

6%

% childhood may be able to predict later onset of depression. Children are asked to rate

the following statements (because the MDI is a strengths-based tool, these questions

Average for all participating are reverse scored):

school districts.

• I feel unhappy a lot of the time.

• I feel upset about things.

• I feel that I do things wrong a lot.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 10

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

ABSENCE OF WORRIES. Anxiety is the most prevalent mental health concern among

Response Options both children and adults. It is estimated that anxiety affects 1 in every 8 children, with

onset starting as early as 6 years old. Although it is one of the most prevalent mental

health issues, studies have found that up to 80% of youths with anxiety do not use

Agree a lot

health services. Children are asked to rate the following statements (because the MDI

Agree a little is a strengths-based tool, these questions are reverse scored):

Don’t agree or disagree

• I worry a lot that other people might not like me.

Disagree a little

Disagree a lot • I worry about what other kids might be saying about me.

• I worry about being teased.

Scoring

High: Children whose average

SELF-REGULATION (SHORT TERM). Self-regulation refers to a person’s ability to

responses were ‘Agree a little’

adapt their behaviour, thoughts or emotions in the context of their environment to

or ‘Agree a lot’

meet a particular goal. Short-term self-regulation specifically involves responding

Medium: Children whose to situations “in the heat of the moment,” such as controlling an impulsive reaction,

average responses were ‘Don’t trying not to fidget in class, or focusing one’s attention on an immediate project or

agree or disagree’ or those activity. Children are asked to rate the following statements:

who reported a mix of positive

and negative responses • When I am sad, I can usually start doing something that will make me

feel better.

Low: Children whose average

responses were ‘Disagree a • After I’m interrupted or distracted, I can easily continue working where

little’ or ‘Disagree a lot’ I left off.

Example Result • I can calm myself down when I’m excited or upset.

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

%

41%

SELF-REGULATION (LONG TERM). While short term self-regulation is often reported in

%

21% younger children, long term self-regulation requires activation of the brain’s prefrontal

38%

% cortex, which is still developing throughout adolescence. This type of self-regulation

involves planning and adapting one’s behaviour in the present to achieve a goal several

Average for all participating days, weeks or even months in the future. Examples include saving one’s allowance

school districts. to buy a desired item, studying for a test, or adapting behaviour to maintain a positive

friendship. Children are asked to rate the following statements:

• If something isn’t going according to my plans, I change my actions to try

and reach my goal.

• When I have a serious disagreement with someone, I can talk calmly about

it without losing control.

• I work carefully when I know something will be tricky.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 11

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

The following questions are included only in the Grade 7 questionnaire.

Response Options RESPONSIBLE DECISION-MAKING. Responsible decision-making involves the

ability to make personal choices that benefit one’s own interests while also being

Agree a lot respectful toward others. This includes being able make realistic appraisals about the

Agree a little consequences of one’s actions. Children are asked to rate the following statements:

Don’t agree or disagree • When I make a decision, I think about what might happen afterward.

Disagree a little

• I take responsibility for my mistakes.

Disagree a lot

• I say “no” when someone wants me to do things that are wrong or dangerous.

Scoring

SELF-AWARENESS. Self-awareness is the ability to accurately recognize the influence

High: Children whose average of personal emotions and thoughts on behaviour. It means being able to accurately

responses were ‘Agree a little’ assess one’s strengths and limitations, while possessing a well-grounded sense of

or ‘Agree a lot’ confidence and optimism. Children are asked to rate the following statements:

Medium: Children whose • When I’m upset, I notice how I am feeling before I take action.

average responses were ‘Don’t

agree or disagree’ or those • I am aware of how my moods affect the way I treat other people.

who reported a mix of positive

• When difficult situations happen I can pause without immediately acting.

and negative responses

Low: Children whose average

PERSEVERANCE. Perseverance refers to the persistent effort to achieve one’s goals,

responses were ‘Disagree a

even in the face of setbacks. For adolescents, it has been associated with higher

little’ or ‘Disagree a lot’

motivation, particularly in the context of school achievement. Children are asked to

rate the following statements:

Example Result

• Once I make a plan to get something done, I stick to it.

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

%

75% • I keep at my schoolwork until I am done with it.

%

19% • I feel a sense of accomplishment from what I do.

6%

%

• I am a hard worker.

Average for all participating • I finish whatever I begin.

school districts.

ASSERTIVENESS. Assertiveness includes the ability or willingness to communicate

one’s point of view; to stand up for oneself, while at the same time respecting the

perspectives of others. During early adolescence, assertiveness has been found to

be particularly important in the context of peer influence, such as in relation to risky

behaviours or engaging in peer victimization. Children are asked to rate the following

statements:

• If I have a reason, I will change my mind.

• If I disagree with a friend, I tell them.

• If I don’t understand something, I will ask for an explanation

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 12

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI PHYSICAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

PHYSICAL HEALTH The MDI questionnaire asks children to evaluate their own physical well-being in

AND WELL-BEING the areas of overall health (perceptions of their own health conditions), body image,

nutrition and sleeping habits. Physical health outcomes are not uniquely controlled

by genetics. They can be affected by different factors or determinants in one’s

environment: family, relationships, lifestyle, economic and social conditions, as well as

the neighbourhoods in which we live. Studies have shown that depression and anxiety

also impact physical health and well-being. Attending to both physical and mental

health is important for maintaining healthy outcomes across the life course.

GENERAL HEALTH. General health is described by The World Health Organization

Response Options (WHO) as “not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” It involves knowing and

recognizing one’s own state of physical well-being. Children are asked the following

questions:

Excellent

• In general, how would you describe your health?

Good

Fair

BODY IMAGE. Body image refers to how people view their own bodies. This measure

Poor becomes especially important during the middle years when children become

increasingly self-aware and self-conscious, comparing themselves to their peers.

Scoring These anxieties are compounded by the onset of puberty, particularly for girls. Body

image dissatisfaction in middle childhood forecasts later depression, low self-esteem,

and eating disorders in both boys and girls. Children are asked the following questions:

High: Children who

responded ‘Excellent’ • How often do you like the way you look?

Medium: Children who

responded ‘Good’

Response Options

Low: Children who responded

Always

‘Fair’ or ‘Poor’

Often

Example Result Sometimes

Hardly ever

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Never

%

48%

%

46%

6%

% • How do you rate your body weight?

Average for all participating

school districts.

Response Options

Very Underweight

Slightly Underweight

About the right weight

Slightly Overweight

Very Overweight

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 13

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI PHYSICAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

BREAKFAST. Eating breakfast not only increases nutrient intake for building strong

Response Options bodies, it also immediately improves cognitive, behavioural, and emotional

functioning, including memory. Studies have found that skipping breakfast is more

common among girls, children in lower socioeconomic families, and among older

Every day

children. Children are asked the following question:

6 times a week

5 times a week • How often do you eat breakfast?

4 times a week

MEALS WITH ADULTS AT HOME. Children who frequently eat meals with family

3 times a week members are more likely to possess social resistance skills used to combat peer-

2 times a week pressure. These children are also more likely to have higher self-esteem, a sense

of purpose and a positive view of the future. Eating meals together helps to build a

Once a week

sense of family connectedness that is known to support children’s well-being during

Never transitions, for example from childhood into early adolescence. Children are asked the

following question:

Scoring • How often do your parents or adult family members eat meals with you?

High: 5 or more times per week JUNK FOOD. Children with increased intake of high fat, high sugar and processed foods

Medium: 3-4 times per week are at risk for obesity, chronic illness, low self-esteem and depression. These children

are also lacking the vitamins and nutrients their bodies need to perform in school

Low: 2 or fewer times per week

and in extracurricular activities. Major benefits of healthy eating on the other hand,

include improvements to cognitive and physical performance as well as psychological

benefits. Children are asked the following question:

Example Result

• How often do you eat food like pop, candy, potato chips or something else?

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

%

67% FREQUENCY OF GOOD SLEEP. School-age children need approximately ten hours

%

6% of sleep a night. Proper sleep not only affects children’s cognitive capacities, but

also helps regulate mood. Children who are not getting enough sleep are at risk for

28%

% developing behavioral problems that closely mimic symptoms associated with ADHD:

hyperactivity, impulsivity and problems sitting still and/or paying attention. Short

Average for all participating

school districts. sleep duration is also associated with the development of obesity from childhood to

adulthood. Children are asked the following questions:

• How often do you get a good night’s sleep?

• What time do you usually go to bed during the weekdays?

Response Options

Before 9:00pm 12

10

9:00pm to 10:00pm

9 3

10:00pm to 11:00pm

11:00pm to 12:00pm 6

After 12:00am

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 14

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI CONNECTEDNESS

CONNECTEDNESS Belonging is a fundamental need for people of all ages. Feeling well-connected is one of

TO ADULTS the most important assets for a child’s well-being. Research shows that children who

do not feel connected are more likely to drop out of school and to suffer from mental

health problems. A single caring adult, be it a family member, a teacher in the school

or a neighbour, can make a very powerful difference in a child’s life. Children who feel

connected report greater empathy towards others, higher optimism, and higher self-

esteem than children who feel less connected.

ADULTS AT SCHOOL. School adults, including teachers, principals and school staff, are

Response Options in a unique position to form meaningful bonds with children. Research shows that the

quality of relationships children have with the adults at their school predicts their levels

of anxiety and conduct challenges. Children who perceive their teachers as caring

Very much true

report feeling more academically and prosocially motivated. Children are asked to rate

Pretty much true the following statements:

A little true At my school there is an adult who:

Not at all true

• really cares about me.

Scoring • believes I will be a success.

• listens to me when I have something to say.

High: children whose average

responses were ‘pretty much’

or ‘very much’ true ADULTS IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD/COMMUNITY. Children who have an adult in their

community to whom they look up to and spend time with report higher self-esteem

Medium: children whose

and life satisfaction, feel more competent in school and are less likely to engage in

responses were ‘a little true’

risky behaviour. Supportive community adults can include coaches, religious leaders,

or those who reported a

friends’ parents and neighbours, as well as doctors or counsellors. Children are asked

mix of positive and negative

to rate the following statements:

responses

In my neighbourhood/community (not from your school or family), there is an adult who:

Low: children whose

responses were on average • really cares about me.

‘not at all true’

• believes that I will be a success.

Example Result • listens to me when I have something to say.

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

ADULTS AT HOME. Attachment research suggests that the relationships children have

%

80% with their primary caregiver(s) serve as a model for all future relationships. A healthy

parent-child relationship enables children to form other healthy relationships that will

%

19%

serve them throughout their lives. Children are asked to rate the following statements:

1%

%

In my home there is a parent or another adult who:

Average for all participating

school districts. • believes I will be a success.

• listens to me when I have something to say.

• I can talk to about my problems.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 15

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI CONNECTEDNESS

NUMBER OF IMPORTANT ADULTS AT SCHOOL.

Response Options School adults, including teachers, principals and school staff, are in a unique position

to observe how children are doing day-to-day and to form meaningful bonds with

2 or More: Children who listed them. Research shows that the quality of relationships children have with the adults

the initials of two or more at their school predicts their levels of anxiety and conduct challenges. Children who

important adults at their school. perceive their teachers as caring report feeling more academically and prosocially

motivated. The MDI questionnaire asks children to list all of the adults from their

One: Children who listed one

school who are important to them. Children are asked the following question:

adult from their school who is

important to them. • Are there any adults who are IMPORTANT TO YOU at your school?

None: Children who did not list If the answer is ‘Yes’, the child is then asked to write the first or last initial of ALL of

any adults from their school who the adults who are important to them.

were important to them.

Why ask the question this way?

Past research has shown that when children are asked to identify the number of

important adults in their lives, they tend to overestimate. Alternatively, when children

% % % are asked to identify each important individual by writing down their initials, they are

2 or more One None

more thoughtful and accurate in identifying the number of adults who are truly making

an impact on their well-being.

The following questions are included only in the Grade 7 questionnaire.

What makes an adult important to you? (Children can select all of the options that apply)

• This person teaches me how to do things that I don’t know.

• I can share personal things and private feelings with this person.

• This person likes me the way I am.

• This person encourages me to pursue my goals and future plans.

• I get to do a lot of fun things with this person or because of this person.

• This person is like who I want to be when I am an adult.

• This person is always fair to me and others.

• This person stands up for me and others when we need it.

• This person lets me make decisions for myself.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 16

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI CONNECTEDNESS

CONNECTEDNESS Beginning in middle childhood, friendships and peer support begin to have a stronger

TO PEERS influence on children’s school motivation, academic achievement and success.

Children begin to place more importance on peer groups than on relationships to

adults. During this phase of human development children need to feel they have

friends they can count on.

PEER BELONGING. During the middle childhood years children begin to associate more

with their peers. Children absorb information from peers about how to behave, who

they are and where they fit. Feeling part of a group can boost self-esteem, confidence

and personal well-being. Peer relationships provide opportunities for learning

cooperation, gaining support, acquiring interpersonal skills and persisting through

Response Options

difficulties. Children are asked the following questions:

Agree a lot • When I am with other kids my age, I feel I belong.

Agree a little

• l feel part of a group of friends that do things together.

Don’t agree or disagree

• I feel that I usually fit in with other kids around me.

Disagree a little

Disagree a lot FRIENDSHIP INTIMACY. During the middle years peer relationships grow in complexity.

Children begin to seek friendships based on quality (having a friend who cares, talks to

Scoring them and helps them with problems) rather than quantity. Close, mutual friendships

provide validation for children’s developing sense of self and self-esteem. Same-age

High: Children whose average friends are also often in a better position than adults to empathize or provide comfort

responses were ‘Agree a little’ during stressful life events such as a transition to a new school, parent separation or

or ‘Agree a lot’ difficulties with other peers. Children are asked the following questions:

Medium: Children whose • I have a friend I can tell everything to.

average responses were ‘Don’t

agree or disagree’ or those • There is somebody my age who really understands me.

who reported a mix of positive

• I have a least one really good friend I can talk to when something is

and negative responses

bothering me.

Low: Children whose average

responses were ‘Disagree a

little’ or ‘Disagree a lot’

Example Result

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

%

75%

%

18%

7%

%

Average for all participating

school districts.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 17

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI USE OF AFTER-SCHOOL TIME

USE OF AFTER- We know that the environments in which children live and play are important, yet

SCHOOL TIME we know very little about how school-aged children actually spend their after-school

hours. The data provided by the MDI attempts to fill gaps in the existing research on

children’s participation in activities during after-school hours (from 3pm to 6pm).

These are known as the “critical hours” because they are the hours in which children

are most often left unsupervised.

Children’s involvement in activities outside of school hours exposes them to important

social environments. After-school activities such as art and music classes, sports

leagues, and community groups provide distinct and important experiences that help

children to build relationship skills and gain competencies. Children who are more

involved in extracurricular activities tend to experience better school success and are

less likely to drop out.

PARTICIPATION IN ORGANIZED AFTER-SCHOOL ACTIVITIES

Response Options Participation in after-school activities has been shown to boost children’s

competence, self-esteem, school engagement, personal satisfaction and academic

5 times a week achievement. After-school activities allow children to meet new friends, to strengthen

existing friendships, and to feel like they belong to a group of peers with shared

4 times a week

interests. For some children, after-school programs can serve as an opportunity to

3 times a week bridge the gap between family and peers. The MDI questionnaire asks children how

Twice a week often they participate in organized activities (ones that are structured and supervised

by a teacher, coach, instructor, volunteer or other adult). Children are asked the

Once a week

following questions:

Never

During the last week from after school to dinner time (about 3pm to 6pm) how

many days did you participate in:

• Educational lessons or activities (e.g. tutoring, math, language school).

Example Result

• Music or art lessons (e.g. drawing, painting, playing a musical instrument).

0% 25% 50% 75% 100% • Youth organizations (e.g. Scouts, Girl Guides, Boys and Girls Clubs).

%

70%

• Individual sports with a coach or instructor (e.g. swimming, dance,

%

10% gymnastics, ice skating, tennis).

21%

%

• Team sports with a coach or instructor (e.g. basketball, hockey, soccer,

football).

Average for all participating

school districts.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 18

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI USE OF AFTER-SCHOOL TIME

DAILY TIME SPENT DOING UNSTRUCTURED ACTIVITIES

Response Options The MDI also explores children’s experiences in unstructured activities. Children

are asked about the type of unstructured activities they are involved in and how

2+ hours per day often they are involved in these activities during after-school hours (3pm to 6pm).

1-2 hours Completing homework assignments, watching television or videos (including Netflix

and YouTube), and computer use are three unstructured activities that children report

30 min to 1 hour spending most of their time on during the after-school period. A balance of several

Less than 30 min activities both structured and unstructured, rather than spending a lot of time on any

Not at all one particular interest or activity, is the most optimal for supporting children’s holistic

(I did not do this activity) development. Children are asked the following question:

During the last week from after school to dinner time (about 3pm to 6pm), how

much time did you spend doing the following activities on a normal day?

• Video/Computer games (Play Station, XBox, Wii, On-line games).

Example Result

• TV, Netflix, YouTube, streaming videos.

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

• Hang out with friends in person.

%

13%

%

14% • Hang out with friends on the phone, tablet or computer.

%

12%

% • Homework.

28%

%

33% • Read for fun.

Average for all participating • Do arts & crafts.

school districts.

• Practice a musical instrument.

• Play sports and/or exercise for fun.

• Volunteer.

Options are included only in the Grade 7 questionnaire

• Work at a job.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 19

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI USE OF AFTER-SCHOOL TIME

WHAT CHILDREN WISH TO BE DOING AFTER SCHOOL. The MDI is the only population-

level survey that asks children what they wish they could be doing. Children are given

two choices to select from:

Think about what you want to do on school days from after school to dinner time

(about 3pm to 6pm).

• I am already doing the activities I want to be doing.

• I wish I could do additional activities.

When a child selects both answers above a third answer is recorded: I am doing some

of the activities I want, but I wish I could do more.

Those children who express that they wish they could be doing additional activities

are asked to list one activity they wish they could do. Because of the open-ended

(qualitative) style of this question, the responses are extremely varied and cannot

be provided in detail within the MDI reports. Instead, responses are coded into the

following categories:

• Physical and/or Outdoor Activities: Team sports, individual sports, being

outside at a park or playground.

• Music and Fine Arts: Music and art lessons/practice, crafts, cooking,

building, writing.

I am already doing the

activities I want to be doing • Friends and Playing: Hanging out with friends, going to a friend’s house,

having friends over, any activity specified with friends, games, talking with

% friends.

• Computer/Video Games: video games, Internet, social media, movies, TV,

YouTube, coding, texting, tablets, cell phones.

I wish I could do

additional activities • Time with Family/at Home: Being at home, spending time with parents,

siblings, grandparents, activities with family members.

% • Work Related Activities: Babysitting, working, paper route.

• Free Time/Relaxing: Time to myself, walk home alone, free time, sleeping,

I am doing some of the activities I

relaxing, reading.

want, but I wish I could do more

% • Other: Shopping, chores, travel, clubs. The “Other” category is also used for

responses that are undecipherable, appear infrequently, or do not fit into a

clear category.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 20

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI USE OF AFTER-SCHOOL TIME

PERCEIVED BARRIERS TO PARTICIPATING IN DESIRED ACTIVITIES. The MDI

questionnaire asks children about the barriers that stop them from participating in

after-school activities. Since the MDI measures children’s perceived barriers, the data

from this question should not be considered a direct measure of the availability of, or

access to, after-school programs or opportunities. Instead, the barriers that children

are reporting should act as a starting point for discussions with parents, schools and

community service providers.

Children are asked to select from the following list of barriers (Children can select all of

the options that apply):

• I have no barriers.

• I have to go straight home after school.

• I am too busy.

• It costs too much.

• The schedule does not fit the times I can attend.

• My parents do not approve.

• I don’t know what’s available.

• I need to take care of siblings or do things at home.

• It is too difficult to get there.

• None of my friends are interested or want to go.

• The activity that I want is not offered.

• I have too much homework to do.

• I am afraid I will not be good enough in that activity.

• It is not safe for me to go.

• Other.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 21

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI SCHOOL EXPERIENCES

SCHOOL Children’s sense of safety and belonging at school has been shown to foster school

success in many ways. When children’s needs in the school environment are met,

they are more likely to feel attached to their school. In turn, children who feel more

EXPERIENCES attached to their school have better attendance and higher academic performance.

These children are also less likely to engage in high-risk behaviours.

The MDI questionnaire asks children about the following school experiences:

academic self-concept, school climate, school belonging, and experiences with peer

victimization. School success is optimized when children perceive that they are

learning within a safe, caring and supportive environment:

Response Options ACADEMIC SELF-CONCEPT. Academic self-concept refers to a child’s beliefs about

their own academic ability, including their perceptions of themselves as students

and how interested and confident they feel at school. Experiencing success and

Agree a lot

receiving consistent positive feedback from parents and teachers greatly influences

Agree a little how children view themselves as learners. Children are asked to rate the following

Don’t agree or disagree statements:

Disagree a little • I am certain I can learn the skills taught in school this year.

Disagree a lot

• If I have enough time, I can do a good job on all my school work.

Scoring • Even if the work in school is hard, I can learn it.

High: Children whose average SCHOOL CLIMATE. School climate is the overall tone of the school environment,

responses were ‘agree a little’ including the way teachers and students interact and how students treat each other.

or ‘agree a lot’ Children’s comfort in their learning environment affects their motivation, enjoyment of

Medium: Children whose school, ability to pay attention in class and academic achievement. An optimal school

average responses were ‘don’t environment is one that values student participation, provides time for self-reflection,

agree or disagree’ or those encourages peer collaboration, and enables students to make decisions about

who reported a mix of positive classroom rules and activities. Children are asked to rate the following statements:

and negative responses

• Teachers and students treat each other with respect in this school.

Low: Children whose average

responses were ‘disagree a • People care about each other in this school.

little’ or ‘disagree a lot’

• Students in this school help each other, even if they are not friends.

Example Result SCHOOL BELONGING. School belonging is the degree to which children feel connected

and valued at their school. Children who feel a sense of belonging at school also report

0% 25% 50% 75% 100% greater happiness and decreased anxiety. Children who experience belonging at

%

85% school have been found to perceive others more favourably and consider the thoughts

and feelings of others more often. Children are asked to rate the following statements:

%

13%

3%

% • I feel like I belong in this school.

Average for all participating

• I feel like I am important to this school.

school districts.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 22

DIMENSIONS OF THE MDI SCHOOL EXPERIENCES

VICTIMIZATION AND BULLYING AT SCHOOL. Bullying is a distinct form of aggressive

Response Options behaviour in which one child or a group of children act intentionally and repeatedly

to cause harm or embarrassment to another child or group of children who have less

power. Being bullied has an enduring effect on a child’s self-esteem. Negative thoughts

Not at all this school year

continue long after the bullying stops.

Once or a few times

Despite recent media attention to the problem of cyber-bullying, it is particularly

About every month social bullying (manipulation, gossip and exclusion) that increases dramatically during

About every week the middle years. The MDI questionnaire asks children about four different types of

bullying. Children are provided with definitions of each type. Children are asked the

Many times a week

following question:

This school year, how often have you been bullied by other students in the following

Example Result ways?

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Cyber: For example, someone used the computer or text messages to exclude,

%

52% threaten, embarrass you, or to hurt your feelings.

%

31% Physical: For example, someone hit, shoved, or kicked you, spat at you, beat you up, or

%

7% damaged or took your things without permission.

6%

% Social: For example, someone left you out, excluded you, gossiped and spread

5%

% rumours about you, or made you look foolish.

Verbal: For example, someone called you names, teased, embarrassed, threatened

Average for all participating you, or made you do things you didn’t want to do.

school districts.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 23

THE WELL-BEING AND ASSETS INDICES

Combining select measures from the MDI helps us paint a fuller picture of children’s overall well-being and the assets that

contribute to their healthy development. The results for key MDI measures are summarized into two indices:

• The Well-Being Index consists of measures relating to children’s physical health and social and emotional development that are

of critical importance during the middle years: Optimism, Self-Esteem, Happiness, Absence of Sadness and General Health.

• The Assets Index consists of measures of key assets that help to promote children’s positive development and well-being. Assets

are resources and influences present in children’s lives such as supportive relationships and enriching activities. The MDI measures

four types of assets: Adult Relationships, Peer Relationships, Nutrition and Sleep, and After-School Activities.

The chart below illustrates the relationship between MDI dimensions and measures, and highlights which measures contribute to

the Well-Being and Assets Indices.

SOCIAL & EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT WELL-BEING INDEX

Optimism Optimism

Self-Esteem Self-Esteem

Happiness Happiness

Absence of Sadness

Absence of Sadness

General Health

PHYSICAL HEALTH & WELL-BEING

General Health

Eating Breakfast

Meals with

Adults at Home

Frequency of

Good Sleep

ASSETS INDEX

ADULT RELATIONSHIPS

Adults at School

CONNECTEDNESS Adults in the Neighbourhood

Adults at Home

Adults at School

Adults in the PEER RELATIONSHIPS

Neighbourhood Peer Belonging

Adults at Home Friendship Intimacy

Peer Belonging

Friendship NUTRITION & SLEEP

Intimacy Eating Breakfast

Meals with Adults at Home

Frequency of Good Sleep

USE OF AFTER-SCHOOL TIME

AFTER-SCHOOL ACTIVITIES

Organized Activities Organized Activities

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 24

THE WELL-BEING AND ASSETS INDICES

THE WELL-BEING INDEX

The Well-Being Index combines MDI measures relating to children’s physical health and social and emotional development that

are of critical importance during the middle years. These are: Optimism, Happiness, Self-Esteem, Absence of Sadness and General

Health.

Scores from these five measures are combined and reported by three categories of well-being, providing a holistic summary of

children’s mental and physical health: ‘Thriving,’ ‘Medium to High’ well-being, or ‘Low’ well-being.

The Well-Being Index combines scores from the following 15 items:

Response Options

Agree a lot OPTIMISM

Agree a little • I have more good times than bad times.

Don’t agree or disagree

• I believe more good things than bad things will happen to me.

Disagree a little

Disagree a lot • I start most days thinking I will have a good day.

SELF-ESTEEM

Scoring

• In general, I like being the way I am.

Thriving: Children who are

reporting positive responses • Overall, I have a lot to be proud of.

on at least 4 of the 5

• A lot of things about me are good.

measures of well-being.

HAPPINESS

Medium to High Well-Being:

Children who are reporting • In most ways my life is close to the way I would want it to be.

neither positive nor negative

responses. • The things in my life are excellent.

• I am happy with my life.

Low Well-Being: Children

• So far I have gotten the important things I want in life.

who are reporting negative

responses on at least one • If I could live my life over, I would have it the same way.

measure of well-being.

ABSENCE OF SADNESS (reverse-scored)

Response Options

% • I feel unhappy a lot of the time.

for General Health

Low

• I feel upset about things. question

Number of

children %

Thriving • I feel that I do things wrong a lot. Excellent

% Good

Medium to GENERAL HEALTH

Fair

High

• In general, how would you describe your health? Poor

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 25

THE WELL-BEING AND ASSETS INDICES

THE ASSETS INDEX

The Assets Index consists of measures of key developmental assets that help to promote children’s positive development and well-

being. Assets are resources and influences present in children’s lives such as supportive relationships and enriching activities. The

Assets Index combines scores from the following 23 items:

ADULT RELATIONSHIPS • At my school there is an adult who really cares about me.

(9 items) • At my school there is an adult who believes I will be a success.

Asset present = • At my school there is an adult who listens to me when I have something to say.

average response is • In my home there is a parent or another adult who believes I will be a success.

“a little true” or higher

• In my home there is a parent or another adult who listens to me when I have

something to say.

• In my home there is a parent or another adult who I can talk to about my problems.

• In my neighbourhood/community (not from your school or family), there is an adult

who really cares about me.

• In my neighbourhood/community (not from your school or family), there is an adult

who believes that I will be a success.

• In my neighbourhood/community (not from your school or family), there is an adult

who listens to me when I have something to say.

PEER RELATIONSHIPS • I feel part of a group of friends.

(6 items) • I feel I usually fit in with other kids.

Asset present = • When I am with other kids my age, I feel I belong.

average response is • I have at least one really good friend I can talk to.

“a little true” or higher • I have a friend I can tell everything to.

• There is somebody my age who really understands me.

NUTRITION AND SLEEP • How often do you eat breakfast?

(3 items) • How often do you get a good night’s sleep?

Asset present = • How often do your parents or other adult family members eat meals with you?

3 or more days per week

AFTER-SCHOOL ACTIVITIES Last week after school (3pm to 6pm), I participated in:

(5 items) • Educational lessons or activities

Asset present = • Art or music lessons

Participates in at least • Youth organizations

one activity

• Individual sports with an instructor

• Team sports with an instructor

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 26

THE WELL-BEING AND ASSETS INDICES

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ASSETS AND WELL-BEING

One of the key findings of the MDI, consistent across all participating school districts, is that children’s self-reported well-being is

related to the number of assets they perceive as being present in their lives. As the number of assets increase, children are more

likely to report higher well-being, and each additional asset is associated with a further increase in well-being.

0-1 30%

2 46%

3 60%

Number of Assets

Number of the following

assets that children report

having in their lives:

4 75%

Adult Relationships

Peer Relationships

After-School Activites

Nutrition and Sleep

5 86%

Positive School Experiences

Percent Experiencing Well-Being

Children who have ‘Medium to High Well-Being’

or are ‘Thriving’ on the Well-Being Index

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 27

MOVING TO ACTION WITH YOUR MDI RESULTS

MDI results can support planning ENGAGE IN CONVERSATIONS

and initiate action within schools, Review your MDI report with as many people as possible: children, parents, teachers,

organizations and communities. school administrators, after-school program staff, local early/middle childhood

committees, librarians, parks and recreation staff, local government and other

There are many opportunities community stakeholders. Highlight strengths and examples of success. Increasing

for working with your MDI local dialogue on the importance of child well-being in the middle years is an excellent

results and there are examples of way to start improving outcomes for children. Identify school and community

successful initiatives from across champions and create an action plan that involves participation from everyone.

the province to learn from. Consider these conversation starters and review the additional resources in the MDI

Tools for Action:

Here, we provide suggestions to

• Which data are you most proud of? Can you identify areas of strength?

help you get started. In addition,

• What beliefs have been confirmed for you through the MDI data?

HELP staff and researchers are

also available to provide support • What surprised you the most?

to MDI initiatives. • Who else should be involved in reviewing these results?

HELP is gathering information • How might the data influence your planning and practices

from schools and communities to

capture stories about using MDI INVOLVE CHILDREN

results.

The results from the MDI survey should be shared with children. Involve them as

If you would like to request much as possible in the interpretation of the data. Get their feedback on how both

support or tell us about your the school and community can better serve their needs. Ask children of all ages for

suggestions on how to improve their school climate and after-school experiences.

experiences using MDI data

Teachers may wish to incorporate the interpretation of MDI data into their classes.

please contact our MDI team: Children tend to offer surprisingly creative solutions that can often be implemented

mdi@help.ubc.ca easily and at no cost.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 28

MOVING TO ACTION WITH YOUR MDI RESULTS

THINK BIG, START SMALL

The MDI provides a lot of rich data. It is easy to feel overwhelmed by all of the

potential ways that schools, communities and governments could begin using the

data to improve child well-being. Moving to action will be more successful if you are

able to focus your efforts on 1 or 2 areas for improvement. There are different ways to

approach the data. You can focus on individual measures, such as Optimism, Bedtimes,

Peer Belonging and Empathy. Alternatively, you can focus on outcomes related to the

Well-Being Index, such as ‘Thriving,’ or Assets Index, such as the presence of positive

Adult Relationships. Questions to consider when identifying an area of focus are:

Which measures resonate the most?

Which measures do you have influence over?

Which measures align with your priorities and goals?

LEARN FROM THE SUCCESS OF OTHERS

Review the data from other neighbourhoods within your school district. Do you see

examples of success that you would like to replicate? Arrange to meet with local

champions to discuss the specific actions they have taken to improve child well-being

in their schools and neighbourhoods. Likewise, you may want to consider sharing local

initiatives with nearby schools and neighbourhoods.

EXPLORE LOCAL DATA

Neighbourhoods have unique characteristics that provide important context for

interpreting MDI results. Understanding neighbourhood-level differences within

a school district or community is important when considering actions to support

children’s well-being. Explore local data by using the Neighbourhood Profiles and

Maps. Both are useful for illustrating and understanding neighbourhood-level strengths

and challenges.

CHECK OUT THE ON-LINE TOOLKIT

The Human Early Learning Partnership has created a Tools for Action webpage. It is

an online resource that will help schools and communities interpret and act upon the

data included in the Middle Years Development Instrument (MDI) reports. You will find

videos, worksheets, print resources and examples of how other communities have used

their MDI data to move to action.

www.earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi/tools

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 29

RELATED RESEARCH & REFERENCES

WHY THE MIDDLE YEARS MATTER

Eccles J. (1999). The development of children ages 6 to 14. The Future of Children, 9 (2):

30-44

Eccles, J. (2004). Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In R. M.

Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (2 ed., pp. 125-153).

New York: John Wiley and sons.

Jacobs R., Reinecke M., Gollan J., Kane P. (2008). Empirical evidence of cognitive

vulnerability for depression among children and adolescents: A cognitive science and

developmental perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 28 (5): 759-782.

Rubin K., Wojslawowics J., Rose-Krasnor L., Booth-LaForce C., Burgess K. (2006).

The Best Friendships of Shy/Withdrawn Children: Prevalence, Stability, and Relationship

Quality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34 (2): 139-153.

DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDITY OF THE MDI

Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2011). Middle childhood inside and out: The psychological and

social worlds of Canadian children ages 9-12, Full Report. Report for the United Way

of the Lower Mainland. Vancouver: University of British Columbia. Available online at

earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi.

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Guhn, M., Gadermann, A. M., Hymel, S., Sweiss, L., &

Hertzman, C. (2013). Development and validation of the Middle Years Development

Instrument (MDI): Assessing children’s well-being and assets across multiple contexts.

Social indicators research, 114(2), 345-369.

CHILDREN’S VOICES

UN General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989,

United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p. 3, available at: http://www.refworld.org/

docid/3ae6b38f0.html [accessed May 2015]

Varni, J. W., Limbers, C. A., & Burwinkle, T. M. (2007). How young can children reliably

and validly self-report their health-related quality of life?: An analysis of 8,591 children

across age subgroups with the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health and quality of life

outcomes, 5(1), 1-13.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 30

RELATED RESEARCH & REFERENCES

SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Diener M., Lucas R. (2004). Adults’ desires for children’s emotions across 48 countries:

Associations with Individual and National Characteristics. Journal of Cross-Cultural

Psychology, 35 (5): 525-547.

Duckworth A., Seligman M. (2005). Self-Discipline Outdoes IQ in Predicting Academic

Performance of Adolescents. Psychological Science, 16 (12): 939-944.

Layous K., Nelson S., Oberle E., Schonert-Reichl K., Lyubomirsky S. (2012). Kindness

Counts: Prompting Prosocial Behavior in Preadolescents Boosts Peer Acceptance and Well-

Being. PLoS ONE, 7 (12): e51380

Oberle E., Schonert-Reichl K., Zumbo B. (2011). Life Satisfaction in Early Adolescence:

Personal, Neighbourhood, School, Family and Peer Influences. Journal of Youth

Adolescence, 40: 889-901.

Oberle E., Schonert-Reichl K., Stwear Lawlor M., Thomson K. (2012). Mindfulness and

Inhibitory Control in Early Adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 32 (4): 565-588.

Oberle E., Schonert-Reichl K., Hertzman C., Zumbo B. (2014). Social–emotional

competencies make the grade: Predicting academic success in early adolescence. Journal of

Applied Developmental Psychology, 35 (3): 138-147.

Olsson C., McGee R., Nada-Raja S., Williams S. (2013). A 32-Year Longitudinal Study of

Child and Adolescent Pathways to Well-Being in Adulthood. Journal of Happiness Studies,

14 (3) 1069-1083.

Schreier H., Schonert-Reichl K., & Chen E. (2013). Effect of volunteering on risk factors

for cardiovascular disease in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Pediatrics,

167 (4): 327-332.

Thomson K., Schonert-Reichl K., Oberle E. (2014). Optimism in Early Adolescence:

Relations to Individual Characteristics and Ecological Assets in Families, Schools, and

Neighborhoods. Journal of Happiness Studies.

PHYSICAL HEALTH AND WELLBEING

Nutrition and Family Meals

Fulkerson J., Story M., Mellin A., Leffert N., Neumark-Sztainer D., French S.

(2006). Family dinner meal frequency and adolescent development: relationships with

developmental assets and high-risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39 (3); 337-

345.

Harrison M., Norris ML., Obeid N., Fu M., Weinstangel H., Sampson M. (2015)

Systematic review of the effects of family meal frequency on psychosocial outcomes in

youth. Canadian Family Physician, 61(2):e96-106.

Larson N., Fulkerson J., Story M., Neumark-Sztainer D. (2013). Shared meals among

young adults are associated with better diet quality and predicted by family meal patterns

during adolescence. Public Health Nutrition Journal, 16 (5): 883-893.

O’Neil A., Quirk S., Housden S., Brennan S., Williams L., Pasco J., Berk M., Jacka

F. (2014). Relationship between diet and mental health in children and adolescents: a

systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 104 (10): e31-42.

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING YOUR MDI RESULTS earlylearning.ubc.ca/mdi 31

RELATED RESEARCH & REFERENCES

Sleep

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2011). Sleep loss in early childhood may contribute

to the development of ADHD symptoms. ScienceDaily. Retrieved April, 2015 from www.

sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/06/110614101122.htm

Falbe J., Davison K., Franckle R., Ganter C., Gortmaker S., Smith L., Land T., Taveras

E. (2015). Sleep Duration, Restfulness, and Screens in the Sleep Environment. Pediatrics,

135 (2).

Hildenbrand A., Daly B., Nicholls E., Brooks-Holliday S., Kloss J. (2013). Increased Risk

for School Violence-Related Behaviors Among Adolescents With Insufficient Sleep. Journal

of School Health, 83 (6): 408-414.

McMakin D, Alfano C. (2015). Sleep and anxiety in late childhood and early adolescence.

Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(6):483-9.

Smaldone A, Honig J., Byrne M. (2007). Sleepless in America: inadequate sleep and

relationships to health and well-being of our nation’s children. Pediatrics, 119 (suppl 1):

S29-S37.

CONNECTEDNESS

Gadermann A., Guhn M., Schonert-Reichl K., Hymel S., Thomson K., Hertzman

C. (2015). A population-based study of children’s well-being and health: the relative

importance of social relationships, health-related activities, and income. Journal of

Happiness Studies, 1-26.

Gifford-Smith, M., Brownell, C. (2003). Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance,

friendship, and peer networks. Journal of School Psychology, 41 (4): 235-284.

Harter S. (1999). The Construction of the Self: A developmental perspective. New York,

NY, US: Guilford Press.

McNeely C., Nonnebaker J., Blum R. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence

from the National Longitudinal Study of School Health. Journal of School Health, 72, 138-

146.

Oberle E., Schonert-Reichl K., Thomson K. (2010). Understanding the link between

social and emotional well-being and peer relations in early adolescence: gender-specific

predictors of peer acceptance. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 39 (11): 1330-1342.

Oberle E., Schonert-Reichl K., Guhn M., Zumbo B., Hertzman C. (2014). The role of

supportive adults in promoting positive development in middle childhood: a population-