Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Introduction To Managerial Economics: Nature of Manageral Economics

Transféré par

Vishal ShanbhagDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Introduction To Managerial Economics: Nature of Manageral Economics

Transféré par

Vishal ShanbhagDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

INTRODUCTION TO MANAGERIAL ECONOMICS

NATURE OF MANAGERAL ECONOMICS MANAGERIAL Economics and Business

economics are the two terms, which, at times have been used interchangeably. Of late,

however, the term Managerial Economics has become more popular and seems to

displace progressively the term Business Economics.

Decision-making and Forward Planning

The prime function of a management executive in a business organization is

decision-making and forward planning. Decision-making means the process of selecting

one action from two or more alternative courses of action whereas forward planning

means establishing plans for the future. The question of choice arises because resources

such as capital, land, labour and management are limited and can be employed in

alternative uses. The decision-making function thus becomes one of making choices or

decisions that will provide the most efficient means of attaining a desired end, say, profit

maximization. Once decision is made about the particular goal to be achieved, plans as to

production, pricing, capital, raw materials, labour, etc., are prepared. Forward planning

thus goes hand in hand with decision-making.

A significant characteristic of the conditions, in which business organizations

work and take decisions, is uncertainty. And this fact of uncertainty not only makes the

function of decision-making and forward planning complicated but adds a different

dimension to it. If knowledge of the future were perfect, plans could be formulated

without error and hence without any need for subsequent revision. In the real world,

however, the business manager rarely has complete information and the estimates about

future predicted as best as possible. As plans are implemented over time, more facts

become known so that in their light, plans may have to be revised, and a different course

of action adopted. Managers are thus engaged in a continuous process of decision-making

through an uncertain future and the overall problem confronting them is one of adjusting

to uncertainty.

In fulfilling the function of decision-making in an uncertainty framework,

economic theory can be pressed into service with considerable advantage. Economic

theory deals with a number of concepts and principles relating, for example, to profit,

demand, cost, pricing production, competition, business cycles, national income, etc.,

which aided by allied disciplines like Accounting. Statistics and Mathematics can be used

to solve or at least throw some light upon the problems of business management. The

way economic analysis can be used towards solving business problems. Constitutes the

subject-matte of Managerial Economics.

Definition:

According to McNair and Meriam, Managerial Economics consists of the use of

economic modes of thought to analyse business situation Spencer and Siegelman have

defined Managerial Economics as “the integration of economic theory with business

practice for the purpose of facilitating decision-making and forward planning by

management”. We may, therefore define Managerial Economics as the discipline which

deals with the application of economic theory to business management. Managerial

1/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

Economics thus lies on the borderline between economics and business management and

serves as abridge between economics and business management and serves as a bridge

between the two disciplines. (See Chart 1)

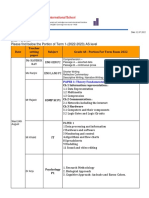

Chart 1 – Economics, Business Management and Managerial Economics.

Economics Business

-Theory and Management

Methodology -Decision Problems

Managerial

Economics

-Application of Economics to

solving business problems

Optimal solutions

To business problems

Aspects of Application

The application of economics to business management or the integration of

economic theory with business practice, as Spencer and Siegelman have put it, has the

following aspects:

1. Reconciling traditional theoretical concepts of economics in relation to the actual

business behavior and conditions. In economic theory, the technique of analysis is

one of model building whereby certain assumptions are made and on that basis,

conclusions as to the behavior of the firms are drown. The assumptions, however,

make the theory of the firm unrealistic since it fails to provide a satisfactory

explanation of that what the firms actually do. Hence the need to reconcile the

theoretical principles based on simplified assumptions with actual business

practice and develops appropriate extensions and reformulation of economic

theory, if necessary.

2. Estimating economic relationships, viz., measurement of various types of

elasticities of demand such as price elasticity, income elasticity, cross-elasticity,

2/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

promotional elasticity, cost-output relationships, etc. the estimates of these

economic relation-ships are to be used for purposes of forecasting.

3. Predicting relevant economic quantities, eg., profit, demand, production, costs,

pricing, capital, etc., in numerical terms together with their probabilities. As the

business manager has to work in an environment of uncertainty, future is to be

predicted so that in the light of the predicted estimates, decision-making and

forward planning may be possible.

4. Using economic quantities in decision-making and forward planning, that is,

formulating business policies and, on that basis, establishing business plans for

the future pertaining to profit, prices, costs, capital, etc. The nature of economic

forecasting is such that it indicates the degree of probability of various possible

outcomes, i.e. losses or gains as a result of following each one of the strategies

available. Hence, before a business manager there exists a quantified picture

indicating the number o courses open, their possible outcomes and the quantified

probability of each outcome. Keeping this picture in view, he decides about the

strategy to be chosen.

5. Understanding significant external forces constituting the environment in which

the business is operating and to which it must adjust, e.g., business cycles,

fluctuations in national income and government policies pertaining to public

finance, fiscal policy and taxation, international economics and foreign trade,

monetary economics, labour relations, anti-monopoly measures, industrial

licensing, price controls, etc. The business manager has to appraise the relevance

and impact of these external forces in relation to the particular business unit and

its business policies.

Chief Characteristics

It would be useful to point out certain chief characteristics of Managerial

Economics, inasmuch it’s they throw further light on the nature of the subject matter and

help in a clearer understanding thereof.

1 Managerial Economics micro-economic in character.

2 Managerial Economics largely uses that body of economic concepts and principles,

which is known as ‘Theory of the firm’ or ‘Economics of the firm’. In addition, it also

seeks to apply Profit Theory, which forms part of Distribution Theories in Economics.

3 Managerial Economics is pragmatic. It avoids difficult abstract issues of economic

theory but involves complications ignored in economic theory to face the overall situation

in which decisions are made. Economic theory appropriately ignores the variety of

backgrounds and training found in individual firms but Managerial Economics considers

the particular environment of decision-making.

4 Managerial Economics belongs to normative economics rather than positive

economics (also sometimes known as descriptive economics). In other words, it is

prescriptive rather than descriptive. The main body of economic theory confines itself to

descriptive hypothesis, attempting to generalize about the relations among different

3/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

variables without judgment about what is desirable or undesirable. For instance, the law

of demand states that as price increases. Demand goes down or vice-versa but this

statement does not tell whether the outcome is good or bad. Managerial Economics,

however, is concerned with what decisions ought to be made and hence involves value

judgments.

Production and Supply Analysis

Production analysis is narrower in scope than cost analysis. Production analysis

frequently proceeds in physical terms while cost analysis proceeds in monetary terms.

Production analysis mainly deals with different production functions and their managerial

uses.

Supply analysis deals with various aspects of supply of a commodity. Certain

important aspects of supply analysis are supply schedule, curves and function, law of

supply and its limitations. Elasticity of supply and Factors influencing supply.

Pricing Decisions, Policies and Practices

Pricing is a very important area of Managerial Economics. In fact, price is the

ness of the revenue of a firm and as such the success of a business firm largely depends

on the correctness of the pries decisions taken by it. The important aspects alt with under

this area is: Price Determination in various Market Forms, Pricing methods, Differential

Pricing, Product-line Pricing and Price Forecasting.

Profit Management

Business firms are generally organized for the purpose of making profits and, in

long run, profits provide the chief measure of success. In this connection, an important

point worth considering is the element of uncertainty exiting about profits because of

variations in costs and revenues which, in turn, are caused by torso both internal and

external to the firm. If knowledge about the future were fact, profit analysis would have

been a very easy task. However, in a world of certainty, expectations are not always

realized so that profit planning and measurement constitute the difficult are

Of Managerial Economics. The important acts covered under this area are: Nature and

Measurement of Profit. Profit iciest and Techniques of Profit Planning like Break-Even

Analysis.

Capital Management

Of the various types and classes of business problems, the most complex and able

some for the business manager are likely to be those relating to the firm’s investments.

Relatively large sums are involved, and the problems are so complex that their disposal

not only requires considerable time and labour but is a term for top-level decision.

Briefly, capital management implies planning and trolls of capital expenditure. The main

topics dealt with are: Cost of Capital. Rate return and Selection of Project.

The various aspects outlined above represent the major uncertainties which a ness

firm has to reckon with, viz., demand uncertainty, cost uncertainty, price certainty, profit

4/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

uncertainty, and capital uncertainty. We can, therefore, conclude the subject-matter of

Managerial Economic consists of applying economic cripples and concepts towards

adjusting with various uncertainties faced by a ness firm.

MANAGERIAL ECONOMICS AND OTHER SUBJECTS

Yet another useful method of throwing light upon the nature and scope of

managerial Economics is to examine is relationship with other subjects. In this

connection, Economics, statistics, Mathematics and Accounting deserve special mention.

Managerial Economics and Economics

Managerial Economics has been described as economics applied to decision-

making. It may be viewed as a special branch of economics bridging the gulf between

pure economic theory and managerial practice.

Economics has two main divisions: microeconomics and macroeconomics.

Microeconomics has been defined as that branch where the unit of study is an individual

or a firm. Macroeconomics, on the other hand, is aggregate in character and has the entire

economy as a unit of study.

Microeconomics, also known as price theory (or Marshallian economics.) Is the

main source of concepts and analytical tools for managerial economics. To illustrate

various micro-economic concepts such as elasticity of demand, marginal cost, the short

and the long runs, various market forms, etc. are all of great significance to managerial

economics. The chief contribution of macro-economics is in the area of forecasting. The

modern theory of income and employment has direct implications for forecasting general

business conditions. As the prospects of an individual firm often depend greatly on

general business conditions, individual firm forecasts depend on general business

forecasts.

A survey in the U.K. has shown that business economists have found the

following economic concepts quite useful and of frequent application:

1. Price elasticity of demand

2. Income elasticity of demand

3. Opportunity cost

4. The multiplier

5. Propensity to consume

6. Marginal revenue product

7. Speculative motive

8. Production function

9. Balanced growth

10. Liquidity preference.

5/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

Business economics have also found the following main areas of economi9cs as

useful in their work

1. Demand theory

2. Theory of the firm-price, output and investment decisions

3. Business financing

4. Public finance and fiscal policy

5. Money and banking

6. National income and social accounting

7. Theory of international trade

8. Economics of developing countries.

Managerial Economics and Accounting

Managerial Economics is also closely related to accounting, which is concerned

with recording the financial operations of a business firm. Indeed, accounting information

is one of the principal sources of data required by a managerial economist for his

decision-making purpose. For instance, the profit and loss statement of a firm tells how

well the firm has done and the information it contains can be used by managerial

economist to throw significant light on the future course of action-whether it should

improve or close down. Of course, accounting data call for careful interpretation.

Recasting and adjustment before they can be used safely and effectively.

It is in this context that the growing link between management accounting and

managerial economics deserves special mention. The main task of management

accounting is now seen as being to provide the sort of data which managers need if they

are to apply the ideas of managerial economics to solve business problems correctly; the

accounting data are also to be provided in a form so as to fit easily into the concepts and

analysis of managerial economics.

USES OF MANAGERIAL ECONOMICS

Managerial economics accomplishes several objectives. First, it presents those

aspects of traditional economics, which are relevant for business decision making it real

life. For the purpose, it culls from economic theory the concepts, principles and

techniques of analysis which have a bearing on the decision making process. These are, if

necessary, adapted or modified with a view to enable the manager take better decisions.

Thus, managerial economics accomplishes the objective of building suitable tool kit from

traditional economics.

Secondly, it also incorporates useful ideas from other disciplines such a

psychology, sociology, etc., if they are found relevant for decision making. In face

managerial economics takes the aid of other academic disciplines having a bearing upon

the business decisions of a manager in view of the carious explicit and implicit

constraints subject to which resource allocation is to be optimized.

6/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

Thirdly, managerial economics helps in reaching a variety of business decisions.

(i) What products and services should be produced?

(ii) What inputs and production techniques should be used?

(iii) How much output should be produced and at what prices it should be sold?

(iv) What are the best sizes and locations of new plants?

(v) How should the available capital be allocated?

Fourthly, managerial economics makes a manager a more competent model

guilder. Thus he can capture the essential relationships which characterize a situation

while leaving out the cluttering details and peripheral relationships.

Fifthly, at the level of the firm, where for various functional areas functional

specialists or functional departments exist, e.g., finance, marketing, personal production,

etc., managerial economics serves as an integrating agent by co-coordinating the different

areas and bringing to bear on the decisions of each department or specialist the

implications pertaining to other functional areas. It thus enables business decision-

making not in watertight compartments but in an integrated perspective, the significance

of which lies in the fact that the functional departments or specialists often enjoy

considerable autonomy and achieve conflicting coals.

Finally, managerial economics takes cognizance of the interaction between the

firm and society and accomplishes the key role of business as an agent in the attainment

of social and economic welfare. It has come to be realized that business part from its

obligations to shareholders has certain social obligations. Managerial economics focuses

attention on these social obligations as constraints subject to which business decisions are

to be taken. In so doing, it serves as an instrument in rehiring the economic welfare of the

society through socially oriented business decisions.

MANAGERIAL ECONOMIST ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITIES

A managerial economist can play a very important role by assisting the

Management in using the increasingly specialized skills and sophisticated techniques

which are required to solve the difficult problems of successful decision-making and

forward planning. That is why, in business concerns, his importance is being growingly

recognized. In advanced countries like the U.S.A., large companies employ one or more

economists. In our country too, big industrial houses have come to recognize the need for

managerial economists, and there are frequent advertisements for such positions. Tatas,

DCM and Hindustan Lever employ economists. Indian Petrochemicals Corporation Ltd.,

a Government of India undertaking, also keeps an economist.

Let us examine in specific terms how a managerial economist can contribute to

decision-making in business. In this connection, two important questions need be

considered:

7/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

1. What role does he play in business, that is, what particular management problems

lend themselves to solution through economic analysis?

2. How can the managerial economist best serve management, that is, what are the

responsibilities of a successful managerial economist?

ROLE OF A MANAGERIAL ECONOMIST

One of the principal objectives of any management in its decision-making process

is to determine the key factors which will influence the business over the period ahead. In

general, these factors can be divided into two-category (i) external and (ii) internal. The

external factors lie outside the control management because they are external to the firm

and are said to constitute business environment. The internal factors he within the scope

and operations of a firm and hence within the control of management, and they are

known as business operations.

To illustrate, a business firm is free to take decisions about what to invest, where

to invest, how much labour to employ and what to pay for it, how to price its products

and so on but all these decisions are taken within the framework of a particular business

environment and the firm’s degree of freedom depends on such factors as the

government’s economic policy, the actions of its competitors and the like.

Environmental Studies

An analysis and forecast of external factors constituting general business

conditions, e.g., prices, national income and output, volume of trade, etc., are of great

significance since every business from is affected by them. Certain important relevant

questions in this connection are as follows:

1. What is the outlook for the national economy? What are the most important local,

regional or worldwide economic trends? What phase of the business cycle lies

immediately ahead?

2. What about population shifts and the resultant ups and downs in regional

purchasing power?

3. What are the demands prospects in new as well as established markets? Will

changes in social behavior and fashions tend to expand or limit the sales of a

company’s products, or possibly make the products obsolete?

4. Where are the market and customer opportunities likely to expand or contract

most rapidly?

5. Will overseas markets expand or contract, and how will new foreign government

legislation’s affect operation of the overseas plants?

6. Will the availability and cost of credit tend to increase or decrease buying? Are

money or credit conditions ahead likely to be easy or tight?

7. What the prices of raw materials and finished products are likely to be?

8. Is competition likely to increase or decrease?

8/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

9. What are the main components of the five-year plan? What are the areas where

outlays have been increased? What are the segments, which have suffered a cut in

their outlay?

10. What is the outlook regarding government’s economic policies and regulations?

What about changes in defense expenditure, tax rates, tariffs and import

restrictions?

11. Will Reserve Bank’s decisions stimulate or depress industrial production and

consumer spending? How will these decisions affect the company’s cost, credit,

sales and profits?

Reasonably accurate answers to these and similar questions can

Enable management’s to chalk out more wisely the scope and direction of their own

business plans and to determine the timing of their specific actions. And it is these

questions which present some of the areas where a managerial economist can make

effective contribution.

The managerial economist has not only to study the economic trends at the

macro-level but must also interpret their relevance to the particular industry/firm where

he works. He has to digest the ever-growing economic literature and advise top

management by means of short, business-like practical notes.

In a mixed economy like India, the managerial economist pragmatically interprets

the intentions of controls and evaluates their impact. He acts as a bridge between the

government and the industry, translating the government’s intentions and transmitting the

reactions of the industry. In fact, government policies charge out of the performance of

industry, the expectations of the people and political expediency.

Business Operations

A managerial economist can also be helpful to the management in making

decisions relating to the internal operations of a firm in respect of such problems as price,

rate of operations, investment, expansion or contraction. Certain relevant questions in this

context would be as follows:

1. What will be a reasonable sales and profit budget for the next year?

2. What will be the most appropriate production Schedules and inventory policies

for the next six months?

3. What changes in wage and price policies should be made now?

4. How much cash will be available next month and how should it be invested?

Specific Functions

A further idea of the role managerial economists can play, can be had from the

following specific functions performed by them as revealed by a survey pertaining to

Britain conducted by K.J.W. Alexander and Alexander G. Kemp:

1. Sales forecasting

9/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

2. Industrial market research.

3. Economic analysis of competing companies.

4. Pricing problems of industry.

5. Capital projects.

6. Production programs.

7. Security/investment analysis and forecasts.

8. Advice on trade and public relations.

9. Advice on primary commodities.

10. Advice on foreign exchange.

11. Economic analysis of agriculture.

12. Analysis of underdeveloped economics.

13. Environmental forecasting.

The managerial economist has to gather economic data, analyze all pertinent

information about the business environment and prepare position papers on issues facing

the firm and the industry. In the case of industries prone to rapid technological advances,

he may have to make a continuous assessment of the impact of changing technology. He

may have to evaluate the capital budget in the light of short and long-range financial,

profit and market potentialities. Very often, he may have to prepare speeches for the

corporate executives.

It is thus clear that in practice managerial economists perform many and varied

functions. However, of these, marketing functions, i.e., sales forecasting and industrial

market research, has been the most important. For this purpose, they may compile

statistical records of the sales performance of their own business and those relating to

their rivals, carry our analysis of these records and report on trends in demand, their

market shares, and the relative efficiency of their retail outlets. Thus while carrying out

their functions; they may have to undertake detailed statistical analysis. There are, of

course, differences in the relative importance of the various functions performed from

firm to firm and in the degree of sophistication of the methods used in carrying them out.

But there is no doubt that the job of a managerial economist requires alertness and the

ability to work under pressure.

Economic Intelligence

Besides these functions involving sophisticated analysis, managerial economist

may also provide general intelligence service supplying management with economic

information of general interest such as competitors prices and products, tax rates, tariff

rates, etc. In fact, a good deal of published material is already available and it would be

useful for a firm to have someone who understands it. The managerial economist can do

the job with competence.

Participating in Public Debates

10/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

May well-known business economists participate in public debates. Their advice

and views are being sought by the government and society alike. Their practical

experience in business and industry ads stature to their views. Their public recognition

enhances their stature in the organization itself.

Indian Context

In the Indian context, a managerial economist is expected to perform the

following functions:

1. Macro-forecasting for demand and supply.

2. Production planning at macro and micro levels.

3. Capacity planning and product-mix determination.

4. Economics of various productions lines.

5. Economic feasibility of new production lines/processes and projects.

6. Assistance in preparation of overall development plans.

7. Preparation of periodical economic reports bearing on various matters such as the

company’s product-lines, future growth opportunities, market pricing situation,

general business, and various national/international factors affecting industry and

business.

8. Preparing briefs, speeches, articles and papers for top management for various

Chambers, Committees, Seminars, Conferences, etc.

9. Keeping management informed o various national and international developments

on economic/industrial matters.

With the adoption of the New Economic Policy, the macro-economic \

Environment is changing fast at a pace that has been rarely witnessed before. And these

changes have tremendous implications for business. The managerial economist has to

play a much more significant role. He has to constantly gauge the possibilities of

translating the rapidly changing economic scenario into viable business opportunities. As

India marches towards globalization, he will have to interpret the global economic events

and find out how his firm can avail itself of the carious export opportunities or of

establishing plants abroad either wholly owned or in association with local partners.

RESPONSIBILITIES OF A MANAGERIAL ECONOMIST

Having examined the significant opportunities before a managerial economist to

contribute to managerial decision-making, let us next examine how he can best serve the

management. For this, he must thoroughly recognize his responsibilities and obligations.

A managerial economist can serve management best only if he always keeps in

mind the main objective of his business, viz., to make a profit on its invested capital. His

academic training and the critical comments from people outside the business may lead a

managerial economist to adopt an apologetic or defensive attitude towards profits. Once

management notices this, his effectiveness is almost sure to be lost. In fact, he cannot

expect to succeed in serving management unless he has a strong personal conviction that

11/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

profits are essential and that his chief obligation is to help enhance the ability of the firm

to make profits.

Most management decisions necessarily concern the future, which is rather

uncertain. It is, therefore, absolutely essential that a managerial economist recognizes his

responsibility to make successful forecasts. By making best possible forecasts and

through constant efforts to improve upon them, he should aim at minimizing, if not

completely eliminating, the risks involved in uncertainties, so that the management can

follow a more orderly course of business planning. At times, he will have to reassure the

management that an important trend will continue; in other cases, he may have to point

out the probabilities of a turning point in some activity of importance to management. In

any case, he must be willing to make considered but fairly positive statements about

impending economic developments, based upon the best possible information and

analysis and stake his reputation upon his judgment. Nothing will build management

confidence in a managerial economist more quickly and thoroughly than a record of

successful forecasts, well documented in advance and modestly evaluated when the

actual results become available.

A few corollaries to the above proposition need also be emphasized here.

First, he has a major responsibility to alert ‘management at the earliest possible

moment in case he discovers an error in his forecast. By promptly drawing attention to

changes in forecasting conditions, he will not only assist management in making

appropriate adjustment in policies and programs but will also be able to strengthen his

own position as a member of the management team by keeping his fingers on the

economic pulse of the business.

Secondly, he must establish and maintain many contacts with individuals and data

sources, which would not be immediately available to the other members of the

management. Extensive familiarity with reference sources and material is essential, but it

is still more important that he knows individuals who are specialists in particular fields

having a bearing on his work. For this purpose, he should join professional associations

and take active part in them. In fact, one of the best means of determining the caliber of a

managerial economist is to evaluate his ability to obtain information quickly by personal

contacts rather than by lengthy research from either readily available or obscure reference

sources. Within any business, there may be a wealth of knowledge and experience but the

managerial economist would be really useful if he can supplement the existing know-how

with additional information and in the quickest possible manner.

Again, if a managerial economist is to be really helpful to the management in

successful decision-making and forward planning, he must be able to earn full status on

the business team. He should be ready and even offer himself to take up special

assignments, be that in study teams, committees or special projects. For, a managerial

economist can only function effectively in an atmosphere where his success or failure can

be traced not only to his basic ability, training and experience, but also to his personality

and capacity to win continuing support for himself and his professional ideas. Of course,

he should be able to express himself clearly and simply and must always try to minimize

the use of technical terminology in communicating with his management executives. For,

it is well known that hat management does not understand, it will almost automatically

12/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

reject. Further, while intellectually he must be in tune with industry’s thinking the wider

national perspective should not be absents from his advice to top management.

Question Bank

1 Define managerial economics with definition

2 How does managerial economics differ from economics?

3 Write a short note on managerial economist

4 Explain the scope of managerial economics

13/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

Demand

Demand

In economic terminology the term demand conveys a wider and definite meaning than in

the ordinary usage. Ordinarily demand means a desire, whereas in economic sense it is

something more than a mere desire. It is interpreted as a want backed up by the-

purchasing power”. Further demand is per unit of time such as per day, per week etc.

moreover it is meaningless to mention demand without reference to price. Considering all

these aspects the term demand can be defined in the following words,

“Demand for anything means the quantity of that commodity, which is bought, at a given

price, per unit of time.”

Law of Demand

This law explains the functional relationship between price of a commodity and the

quantity demanded of the same. It is observed that the price and the demand are

inversely related which means that the two move in the opposite direction. An

increase in the price leads to a fall in the demand and vice versa. This relationship can

be stated as

“Other things being equal, the demand for a commodity varies inversely as the price”

OR

“The demand for a commodity at a given price is more than what it would be

at a higher price and less than what it would be at a lower price”

Demand Schedule and Demand Curve

These are the two devices to present the law. The demand schedule is a schedule

or a table which contains various possible prices of a commodity and different

quantities demanded at them. It can be an individual demand schedule

representing the demand of an individual consumer or can be the market demand

schedule showing the total demand of all the consumers taken together, this is

indicated in the following table.

Price per Individual Demand Schedule (Quantity in liter Market Demand

Liter in Demand by Different Individuals) (Daily Demand) Schedule

Rs. (Daily Demand

24 1.00 0.75 0.50 0.00 75

22 1.25 1.00 0.75 0.50 100

20 1.5 1.25 1.00 0.75 125

18 1.75 1.5 1.25 1.00 150

It can be observed that with a fall in price every individual consumer buys a larger

quantity than before as a result of which the total market demand also rises. In

case of an increase in price the situation will be reserved. Thus the demand

schedule reveals the inverse price-demand relationship, i.e. the law of demand.

14/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

Demand Curve

It is a geometrical device to express the inverse price-demand relationship, i.e. the law of

demand. A demand curve can be obtained by plotting a demand schedule on a graph and

joining the points so obtained, like the demand schedule we can derive an individual

demand curve as well as a market demand curve. The former shows the demand curve of

an individual buyer while the latter shows the sum total of all the individual curves i.e. a

market or a total demand curve. The following diagram shows the two types of demand

curves.

In the above diagram, figure A shows an individual demand curve-of the consumer A in

the above schedule-while figure B indicates the total market demand. It can be noticed

that both the curves are negatively sloping or downwards sloping from left to right. Such

a curve shows the inverse relationship between the two variables. In this case the two

variable are price on Y axis and the quantity demanded on X axis. It may be noted that at

a higher price OP the quantity demanded is OM while at a lower price say OP, the

quantity demanded rises to OM thus a demand curve diagrammatically explains the law

of demand.

Assumptions of Law

The law of demand in order to establish the price-demand relationship makes a number of

assumptions as follows:

Income of the consumer is given and constant.

No change in tastes, preference, habits etc.

Constancy of the price of other goods.

No change in the size and composition of population.

These Assumptions are expressed in the phrase “other things remaining equal”.

Exceptions of the Law

In case of major bulk of the commodities the validity of the law is experienced.

However there are certain situations and commodities which do not follow the law.

These are termed as the exceptions to the law; these can be expressed as follows.

15/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

(1) Continuous changes in the price lead to the exceptional behavior. If the price shows

a rising trend a buyer is likely to buy more at a high price for protecting himself against a

further rise. As against it when the price starts falling continuously, a consumer buys less

at a low price and awaits a further in price.

(2) Giffens’s Paradox describes a peculiar experience in case of inferior goods. When

the price of an inferior commodity declines, the consumer, instead of purchasing more,

buys less of that commodity and switches on to a superior commodity. Hence the

exception.

(3) Conspicuous Consumption refers to the consumption of those commodities which

are bought as a matter of prestige. Naturally with a fall in the price of such goods, there is

no distinction in buying the same. As a result the demand declines with a fall in the price

of such prestige goods.

(4) Ignorance Effect implies a situation in which a consumer buys more of a commodity

at a higher price only due to ignorance.

In the exceptional situations quoted above, the demand curve becomes an upwards rising

one as shown in the alongside diagram.

In the alongside figure, the demand curve is positively sloping one due to which more is

demanded at a high price and less at a low price.

Determinants of Demand

The law of demand, while explaining the price-demand relationship assumes other factors

to be constant. In reality however, these factors such as income, population, tastes, habits,

preferences etc., do not remain constant and keep on affecting the demand. As a result the

demand changes i.e. rises or falls, without any change in price.

(1) Income: The relationship between income and the demand is a direct one. It means

the demand changes in the same direction as the income. An increase in income leads to

rise in demand and vice versa.

(2) Population: The size of population also affects the demand. The relationship is a

direct one. The higher the size of population, the higher is the demand and vice versa.

(3) Tastes and Habits: The tastes, habits, likes, dislikes, prejudices and preference etc.

of the consumer have a profound effect on the demand for a commodity. If a consumers

dislikes a commodity, he will not buy it despite a fall in price. On the other hand a very

high price also may not stop him from buying a good if he likes it very much.

(4) Other Prices: This is another important determinant of demand for a commodity. The

effects depends upon the relationship between the commodities in question. If the price of

a complimentary commodity rises, the demand for the commodity in reference falls. E.g.

the demand for petrol will decline due to rise in the price of cars and the consequent

decline in their demand. Opposite effect will be experienced incase of substitutes.

16/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

(5) Advertisement: This factor has gained tremendous importance in the modern days.

When a product is aggressively advertised through all the possible media, the consumers

buy the advertised commodity even at a high price and many times even if they don’t

need it.

(6) Fashions: Hardly anyone has the courage and the desire to go against the prevailing

fashions as well as social customs and the traditions. This factor has a great impact on the

demand.

(7) Imitation: This tendency is commonly experienced everywhere. This is known as the

demonstration effects, due to which the low income groups imitate the consumption

patterns of the rich ones. This operates even at international levels when the poor

countries try to copy the consumption patterns of rich countries.

Changes in Demand

The law of demand explains the effect of only-one factor viz., price, on the demand for a

commodity, under the assumption of constancy of other determinants. In practice, other

factors such as, income, population etc. cause the rise or fall in demand without any

change in the price. These effects are different from the law of demand. They are termed

as changes in demand in contrast to variations in demand which occur due to changes in

the price of a commodity. In economic theory a distinction is made between (a) variations

i.e. extension and contraction in demand due to price and (b) Changes i.e. increase and

decrease in demand due to other factors.

(a) Variations in demand refer to those which occur due to changes in the price of a

commodity.

These are two types.

(1) Extension of Demand: This refers to rise in demand due to a fall in price of the

commodity. It is shown by a downwards movement on a given demand curve.

(2) Contraction of Demand: This means fall in demand due to increase in price and can

be shown by an upwards movement on a given demand curve.

(b) Changes in demand imply the rise and fall due to factors other than price. It means

they occur without any change in price. They are of two types.

(1) Increase in Demand: This refers to higher demand at the same price and results from

rise in income, population etc., this is shown on a new demand curve lying above the

original one.

(2) Decrease in demand: It means less quantity demanded at the same price. This is the

result of factors like fall in income, population etc. this is shown on a new demand lying

below the original one.

17/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

Fig (A) Extension/Contraction of Demand

Fig (B) Increase/Decrease in Demand

In figure A, the original price is OP and the Quantity demanded is OQ. With a rise in

price from OP to Op1 the demand contracts from OQ to Oq1 and as a result of fall in

price from OP to OP2, the demand extends from OQ to OQ2.

In figure, B an increase in demand is shown by a new demand curve, D1 while the

decrease in demand is expressed by the new demand curve D2, lying above and below

the original demand curve D respectively. On D1 more is demand (OQ1) at the same

price while on D2 less is demanded (OQ2) at the same price OP.

Elasticity of Demand

The law of demand explains the functional relationship between price and demand. In

fact, the demand for a commodity depends not only on the price of a commodity but

also on other factors such as income, population, tastes and preferences of the

consumer. The law of demand assumes these factors to be constant and states the

inverse price-demand relationship. Barring certain exceptions, the inverse price-

demand relationship holds good in case of the goods that are bought and sold in the

market.

The law of demand explains the direction of a change as it states that with a rise in

price the demand contracts and with a fall in price it expands. However, it fails to

explain the extent or magnitude of a change in demand with a given change in price.

In other words, the law of demand merely shows the direction in which the demand

changes as a result of a change in price, but does not throw any light on the amount

by which the demand will change in response to a given change in price. Thus, the

law of demand explains the qualitative but not the quantitative aspect of price-

demand relationship.

Although it is true that demand responds to change in price of a commodity, such

response varies from commodity to commodity. Some commodities are more

responsive or sensitive to change in price while some others are less. The concept of

18/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

the elasticity of demand has great significance as it explains the degree of

responsiveness of demand to a change in price. It thus elaborates the price-demand

relationship. The elasticity of demand thus means the sensitiveness or responsiveness

of demand to a change in price.

According to Marshall, “the elasticity (or responsiveness) of demand in a market

is great or small accordingly as the demand changes (rises or falls) much or little

for a given change (rise or fall) in price.”

From the above discussion, it will be clear that thought different commodities react to

a change in price in the same direction; the degree of their response differs. Demand

for some commodities is more sensitive or responsive to a change in price, while it is

less responsive for some others. Elasticity of demand is a measure of relative changes

in the amount demanded in response to a small change in price. Certain goods are

said to have an elastic demand while others have an inelastic demand. The demand is

said to be elastic when a small change in price brings about considerable change in

demand. On the other hand, the demand for a good is said to be inelastic when a

change in price fails to bring about significant change in demand.

The concept of elasticity can be expressed in the form of an equation as:

Ep = Percentage change in quantity demanded/Percentage change in the price

Types of Price Elasticity

The concept of price elasticity reveals that the degree of responsiveness of demand to

the change in price differs from commodity to commodity. Demand for some

commodities is more elastic while that for certain others is less elastic. Using the

formula of elasticity, it possible to mention following different types of price

elasticity:

(1) Perfectly inelastic demand (ep = o).

(2) Inelastic (less elastic) demand (e< 1)

(3) Unitary elasticity (e = 1).

(4) Elastic (more elastic) demand (e> 1).

(5) Perfectly elastic demand (e = x)

(1) Perfectly Inelastic Demand (ep = o).

This describes a situation in which demand shows no response to a change in price. In

other words, whatever be the price the quantity demanded remains the same. It can be

depicted by means of the alongside diagram.

The vertical straight line demand curve as shown alongside reveals that with a change in

price (from OP to Op1) the demand remains same at OQ. Thus, demand does not at all

respond to a change in price. Thus ep = O. Hence, perfectly inelastic demand. Fig a

(2) Inelastic (less elastic) Demand (e < 1):

In this case the proportionate change in demand is smaller than in price. The

alongside figure shows this type.

19/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

In the alongside figure percentage change in demand is smaller than that in price. It

means the demand is relatively c less responsive to the change in price. This is referred to

as an inelastic demand. Fig e

(3) Unitary Elasticity (e = 1):

When the percentage change in price produces equivalent percentage change in demand,

we have a case of unit elasticity. The rectangular hyperbola as shown in the figure

demonstrates this type of elasticity. In this case percentage change in demand is equal to

percentage change in price, hence e = 1. Fig c

(4) Elastic Demand (e> > 1):

In case of certain commodities the demand is relatively more responsive to the change in

price. It means a small change in price induces a significant change in, demand. This can

be understood by means of the alongside figure.

It can be noticed that in the above example the percentage change in demand is greater

than that in price. Hence, the elastic demand (e>1) Fig d

(5) Perfectly Elastic Demand (e = x):

This is experienced when the demand is extremely sensitive to the changes in price. In

this case an insignificant change in price produces tremendous change in demand. The

demand curve showing perfectly elastic demand is a horizontal straight line. Fig b

It can be noticed that at a given price an infinite quantity is demanded. A small change in

price produces infinite change in demand. A perfectly competitive firm faces this type of

demand.

From the above analysis it can be concluded that theoretically five different types of price

elasticity can be mentioned. In practice, however two extreme cases i.e. perfectly elastic

and perfectly inelastic demand, are rarely experienced. What we really have is more

elastic (e 1) or less elastic (e 1 ) demand. The unitary elasticity is a dividing line between

these two cases.

20/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

Determinants of Elasticity

The nature of demand for a commodity, i.e. whether the demand is elastic or inelastic

depends upon many factors. Though it is difficult to state precisely the nature of demand

for a particular commodity, it is possible to classify the commodities under broad

categories and make certain generalizations regarding whether the demand for

commodities belonging to a certain group is elastic or inelastic.

(1) Nature of the Commodity: Humans wants, i.e. the commodities satisfying them can

be classified broadly into necessaries on the one hand and comforts and luxuries on the

other hand. The nature of demand for a commodity depends upon this classification. The

demand for necessities is inelastic and for comforts and luxuries it is elastic.

(2) Number of Substitutes Available: The availability of substitutes is a major

determinant of the elasticity of demand.

The large the number of substitutes, the higher is the elastic. It means if a commodity

has many substitutes, the demand will be elastic. As against this in the absence of

substitutes, the demand becomes relatively inelastic because the consumers have no other

alternative but to buy the same product irrespective of whether the price rises or falls.

(3) Number Of Uses: If a commodity can be put to a variety of uses, the demand will be

more elastic. When the price of such commodity rises, its consumption will be restricted

only to more important uses and when the price falls the consumption may be extended to

less urgent uses, e.g. coal electricity, water etc.

21/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

(4) Possibility of Postponement of Consumption: This factor also greatly influences the

nature of demand for a commodity. If the consumption of a commodity can be postponed,

the demand will be elastic.

(5) Range of prices: The demand for very low-priced as well as very high-price

commodity is generally inelastic. When the price is very high, the commodity is

consumed only by the rich people. A rise or fall in the price will not have significant effect

in the demand. Similarly, when the price is so low that the commodity can be brought by all those who

wish to buy, a change, i.e., a rise or fall in the price, will hardly have any effect on the demand.

(6) Proportion of Income Spent: Income of the consumer significantly influences the

nature of demand. If only a small fraction of income is being spent on a particular

commodity, say newspaper, the demand will tend to be inelastic.

(7) According to Taussig, unequal distribution of income and wealth makes the demand

in general, elastic.

(8) In addition, it is observed that demand for durable goods, is usually elastic.

(9) The nature of demand for a commodity is also influenced by the complementarities

of goods.

From the above analysis of the determinants of elasticity of demand, it is clear that no

precise conclusion about the nature of demand for any specific commodity can be drawn.

It depends upon the range of price, and the psychology of the consumers. The conclusion

regarding the nature of demand should, therefore be restricted to small changes in prices

during short period. By doing so, the influence of changes in habits, tastes, likes customs

etc., can be ignored.

Measurement of Elasticity

For practical purposes, it is essential to measure the exact elasticity of demand. By

measuring the elasticity we can know the extent to which the demand is elastic or

inelastic. Different methods are used for measuring the elasticity of demand.

(1) Percentage Method: In this method, the percentage change in demand and

percentage change in price are compared.

ep = Percentage change in demand / Percentage change in price

In this method, three values of ‘ep’ can be obtained. Viz., ep = 1, ep >1, ep <1.

(a) If 5% change in price leads to exactly 5% change in demand, i.e. percentage change in

demand is equal to percentage change in price , e = 1, it is a case of unit elasticity .

(b) If percentage change in demand is greater than percentage change in price, e> 1, it

means the demand is elastic.

(c) If percentage change in demand is less than that in price, e 1, meaning thereby the

demand is inelastic.

(2) Total Outlay Method: The elasticity of demand can be measured by considering the

changes in price and the consequent changes in demand causing changes in the total

amount spent on the goods. The change in price changes the demand for a commodity

which in turn changes the total expenditure of the consumer or total revenue of the seller.

22/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

(a) If a given change in price fails to bring about any change in the total outlay, it is the

case of unit elasticity. It means if the total revenue (price x Quantity bought) remains the

same in spite of a change in price, ‘ep’ is said to be equal to 1.

(b) If price and total revenue are inversely related, i.e., if total revenue falls with rise in

price or rises with fall in price, demand is said to be elastic or e 1.

(c) When price and total revenue are directly related, i.e. if total revenue rises with a rise

in price and falls with a fall in price, the demand is said to be inelastic pr e <1.

(3) Point Method: Another suggested by Marshall is to measure elasticity at a point on a

straight line. This method can be better understood with the help of a diagram as given

below:

In the Fig. DD1 is a straight line demand curve meeting the two axes at D and D1. A is

any point on the demand curve at which the elasticity is to be measured. The formula for

measuring the same at a point say ‘A’ is-

ep = Lower segment of the demand curve AD1/ Upper segment of the demand

curve =AD

It will be observed from Fig. that at different points on the demand curve the elasticity

will be different.

Thus, at mid-point e=1, above the mid-point e I and below the I-point e<1. at a point

where the curve intersects X axis, e = o and point at which it meets Y axis, e =

Income Elasticity of Demand

The discussion of price elasticity of demand reveals that extent of change in demand as a

result of change in price. However, as already explained, price is not the only determinant

of demand. Demand for a commodity changes in response to a change in income of the

consumer. In fact, income effect is a constituent of the price effect. The income effect

suggests the effect of change in income on demand. The income elasticity of demand

explains the extent of change in demand as a result of change in income. In other words,

income elasticity of demand means the responsiveness of demand to changes in income.

Thus, income elasticity of demand can be expressed as:

EY =Percentage change in demand /Percentage change in income

The following types of income elasticity can be observed:

(1) Income Elasticity of Demand Greater than One: When the percentage change

in demand is greater than the percentage change in income, a greater portion of

income is being spent on a commodity with an increase in income- income elasticity

is said to be greater than one.

(2) Income Elasticity is unitary: When the proportion of income spent on a

commodity remains the same or when the percentage change in income is equal to the

percentage change in demand, EY = 1 or the income elasticity is unitary.

(3) Income Elasticity Less Than One (EY< < 1): This occurs when the percentage

change in demand is less than the percentage change in income.

23/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

(4) Zero Income Elasticity of Demand (EY=o): This is the case when change in

income of the consumer does not bring about any change in the demand for a

commodity.

(5) Negative Income Elasticity of Demand (EY< < o): It is well known that income

effect for most of the commodities is positive. But in case of inferior goods, the

income effect beyond a certain level of income becomes negative. This implies that as

the income increases the consumer, instead of buying more of a commodity, buys less

and switches on to a superior commodity. The income elasticity of demand in such

cases will be negative.

Cross Elasticity of Demand

While discussing the determinants of demand for a commodity, we have observed that

demand for a commodity depends not only on the price of that commodity but also on the

prices of other related goods. Thus, the demand for a commodity X depends not only on

the price of X but also on the prices of other commodities Y, Z….N etc. The concept of

cross elasticity explains the degree of change in demand for X as, a result of change in

price of Y. this can be expressed as-

EC =Percentage Change in demand for X / Percentage change in price of Y

The relationship between any two goods is of two types. The goods X and Y can be

complementary goods (such as pen and ink) or substitutes (such as pen and ball pen). In

case of complementary commodities, the cross elasticity will be negative. This means

that fall in price of X (pen) leads to rise in its demand so also rise in t) demand for Y

(ink) On the other hand, the cross elasticity for substitutes is positive which means a fall

in price of X (pen) results in rise in demand for X and fall in demand for Y (ball pen). If

two commodities, say X and Y, are unrelated there will be no change i. Demand for X as

a result of change in price of Y. Cross elasticity in cad of such unrelated goods will then

be zero.

In short, cross elasticity will be of three types:

(1) Negative cross elasticity – Complementary commodities.

(2) Positive cross elasticity – Substitutes.

(3) Zero cross elasticity – Unrelated goods.

Importance of elasticity

The concept of elasticity is of great importance both in economic theory and in practice.

(1) Theoretically, its importance lies in the fact that it deeply analyses the price-demand

relationship. The law of demand merely explains the qualitative relationship while the

concept of elasticity of demand analyses the quantitative price-demand relationship.

(2) The Pricing policy of the producer is greatly influenced by the nature of demand for

his product. If the demand is inelastic, he will be benefited by charging a high price. If on

the other hand, the demand is elastic, low price will be advantageous to the producer. The

concept of elasticity helps the monopolist while practicing the price discrimination.

24/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

(3) The price of joint products can be fixed on the basis of elasticity of demand. In case

of such joint products, such as wool and mutton, cotton and cotton seeds, separate costs

of production are not known. High price is charged for a product having inelastic demand

(say cotton) and low price for its joint product having elastic demand (say cotton seeds.)

(4) The concept of elasticity of demand is helpful to the Government in fixing the prices

of public utilities.

(5) The Elasticity of demand is important not only in pricing the commodities but also in

fixing the price of labour viz., wages.

(6) The concept of elasticity of demand is useful to Government in formulation of

economic policy in various fields such as taxation, international trade etc.

(a) The concept of elasticity of demand guides the finance minister in imposing the

commodity taxes. He should tax such commodities which have inelastic demand so that

the Government can raise handsome revenue.

(b) The concept of elasticity of demand helps the Government in formulating commercial

policy. Protection and subsidy is granted to the industries which face an elastic demand.

(7) The concept of elasticity of demand is very important in the field international trade.

It helps in solving some of the problems of international trade such as gains from trade,

balance of payments etc. policy of tariff also depends upon the nature of demand for a

commodity.

In nutshell, it can be concluded that the concept of elasticity of demand has great

significance in economic analysis. Its usefulness in branches of economic such as

production, distribution, public finance, international trade etc., has been widely

accepted.

Question bank

1. Write a short note on

(i) Law of demand

2 Explain briefly how the demand for a commodity is affected by changes in

price. In come, price of substitute, advertisement ad population.

3 Define price elasticity of demand ad distinguish between its various types.

Discuss the role of price elasticity of demand in business decision

4 Define elasticity of demand .explain with diagrams the cases where the

absolutely value of elasticity is (i) zero (ii) infinity (iii) one (iv) less than one

(v) more than one

25/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

Supply

The term “Supply” is one of the important terms in economic. It implies various

amounts or quantities of a good offered for sale at various prices. Mayers has defined

this term in the following words:

“We may define ‘supply’ as a schedule of the amount of a good that would be offered for

sale at all possible prices at any one instant of time, or during any one period of time, for

example, a day, a week and so on, in which the conditions of supply remain the same.”

Analysis of the above definition implies that:

(i) It is a schedule of the amount of a good which is offered for sale at all possible

prices.

(ii) The amount of a good is offered for sale at a given time, which may be a day, a

week, a month and so on.

(iii) During the given period of time, the conditions of supply remain unchanged.

(iv) The supplier is able and willing to supply the good at a given price.

Thus, supply implies the willingness and ability on the part of a person (supplier) to

sell a good in different quantities at a certain price and time.

Distinction between Stock and Supply

In ordinary languages the two terms viz., stock and supply are used interchangeably.

However, strictly in economic sense the two terms convey different meaning. The

distinction between the two can be explained as follows:

(1) Stock is a reservoir while supply is a flow.

(2) At any time Stock is bigger than supply because supply represents only a part of

total stock.

(3) Supply refers to the actual Quantity offered for sale at the prevailing price while

stock means the potential supply.

(4) Supply is more elastic than stock.

Law of Supply

Supply, like demand, is a function of price. It means a change in price brings about a

change in supply. The law of supply explains the functional relationship between price

and supply. The law is stated in the following words:

“In a given market at any given time, the quantity of any goods which people are ready to

offer for sale generally varies directly with the price.”

If this statement of law of supply is analyzed, it will show that:

(i) Price and supply vary or change in the same direction. This means that if price of a

good rises, its supply will increase and if its price falls, supply thereof will contact.

(ii) The supply position holds good at a particular time. This means that a particular

quantity of a good will be offered at a certain price at a particular point of time.

This law may also be stated in the following words: “Other things remaining the same, as

the price of a commodity rises, its supply is extended and as the price falls its supply is

contracted.”

26/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

Supply Schedule and Supply Curve:

The law of supply can be explained by means of a supply schedule and a supply curve.

Supply Schedule: It is a table or schedule that shows different quantities of a commodity

that are offered for sale at a particular time. Supply schedule can be (i) individual supply

schedule, (ii) Market supply schedule. The former relates to the quantity that an

individual firm or producer or supplier is willing and able to offer for sale at different

prices.

The market supply refers to the sum total of the quantities of a commodity offered for

sale by different individual suppliers at different prices per unit of time. The following

schedule makes the point clear:

Price per kg S1 S2 S3 S4 Total market

supply

2.00 20 35 40 500

3.00 30 45 50 700

4.00 40 50 55 1000

5.00 45 55 60 1200

6.00 50 60 65 1500

In the above schedule supply of different individual firms is shown as S1, S2, S3, etc.

likewise there can be many other supplier in the market. The last column shows the

market supply which is obtained by summing up the individual supplies of different firms

at different prices.

It can be noticed that the reaction of an individual supplier to the change in price is

similar. It implies that as the price rises every individual seller offers a larger quantity for

sale. Since the market supply is nothing but the sum total of the individual supplies, it is

obvious that it changes in the same direction. Hence as the price rises the supply

increases. Thus, the supply schedules explain the direct relationship between price and

quantity supplied.

Supply Curve: Supply curve is a geometrical device to express the price-supply

relationship. Such curves can be obtained for every firm separately as well as for the

entire market. Accordingly, we get individual supply curve as also the market supply

curve.

Supply curve is thus, a graphical presentation of the law of supply. If the points in the

above schedule are plotted and the positions so obtained are joined we get a supply curve

as shown in the following diagrams:

27/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

In the above diagrams price is measured along the vertical Y axis while the quantity

supplied is measured along the horizontal ‘X’ axis. Different positions showing price and

the corresponding quantity supplied are joined to get the supply curve.

S1, S2, S3 are the three individual supply curves while the last figure shows the market

supply (SM). It can be observed that as the price rises more is supplied. Hence the supply

curve is rising upwards to the right or positively sloping. Such curve indicates price

supply relationship.

The law of supply, which states that price and supply are directly related, can thus be

expressed by means of supply schedule and supply curve.

Explanation of the law

Individual Supply: An individual firm is interested in securing maximum profits from

its supply. Obviously, at a certain price it will supply the quantity at which the profits are

28/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

maximum. In order to derive the profits an individual seller has to take into account the

cost of production and compare the same with price to calculate his profits.

Generally, it is observed that as the production and supply increase the per unit cost

goes on increasing. Naturally, a firm will not be able and willing to supply more

quantity unless the price is higher. In other words, higher price offers an inducement

to firm for offering larger quantity. thus, more will be supplied at a high price and less

at a low price. Hence, the direct relationship.

Moreover, every commodity has a reservation price which means the minimum price

expected by the producer. If the actual price is less than the reservation price no supply

will be forthcoming. As the price rises more will be supplied.

Market Supply: As mentioned earlier market supply is the sum total of individual

supply. Naturally, it will behave in the same way as the individual supply in response to

change in price.

Expansion of Market Supply occurs at a high price, because

(i) The Existing suppliers supply larger quantity.

(ii) New suppliers enter the market.

Contraction of market supply occurs due to

(i) Reduction in supply by some firms,

(ii) Exit from the market of certain other firms who cannot supply any quantity at the new

low price.

Thus, both the individual as well as the market supply change in the same direction as the

price.

Determinants of Supply

The law of supply explains the functional relationship between price and supply. Price,

though important, is not the only determinant of supply. There are many factors along

with price which cause changes in supply.

(i) Price: A change in price of a given good may bring about a change in the supply

position. If price rises, generally, supply will increase and vice versa.

(ii) Production cost: If production-cost changes, the supply; position may also change. If

cost of production rises, production may be curtailed and hence, the supply may be

reduced and if the cost of production declines, the situation will be just opposite.

(iii) Factors of production: If the price of factors of production changes, there would be

change in the volume of production and with that there would be a change in the supply

position.

(iv) Transport facilities etc. It means if communications and transport are improved,

supply can be increased. If these means are not adequate, efficient or economical, the

supply may decrease.

(v) Future trends in prices: if future trends in prices indicate the possibility of rise in the

price, the present supply will decrease and vice versa.

(vi) Nature factors: If weather conditions are favorable, supply will increase and in case

of unfavorable weather conditions, the same will decrease, similarly, if natural calamities

occur, the supply will be reduced.

(vii) Abnormal circumstances: It may be pointed out that if some abnormal

circumstances, like war etc. develop, the supply position may change. During the war

29/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

time supply may be reduced. But if hostilities are over, there can be increase in the

supply.

(viii) Monetary policy of the Government: Lastly, it may be pointed out that the monetary

policy of the Government may also change the supply position. If liberal monetary policy

is adopted by the Government, it is possible that production may increase and as such, the

supply may also increase. If however, the Government adopts tight monetary policy,

opposite may happen.

Increase/Decrease and Extension/Contraction of Supply

(a) Extension and Contraction of Supply: The law of supply expresses the functional

relationship between price and supply and states that the two are directly related. The

variations in supply i.e. rise or fall in it, brought about due to changes in the price are

called extension and contraction of supply respectively. Thus, Extension of supply

means higher quantity supplied at a high price while Contraction of supply refers to fall

in supply due to a fall in the price of a commodity. Such changes can be shown by means

of the following

In the alongside diagram price of good is measured along Y axis while quantity supplied

along ‘X’ axis. Originally, at price ‘OP’ the quantity supplied is OQ.

(1) As the price rises to ‘OP1’ the. Supply rises to ‘OQ1’ thus ‘QQ1’ is the extension of

supply.

(2) As the price falls to ‘OP2’ the supply falls to ‘OQ2’. QQ2’ therefore, shows

contraction of supply.

(b) Increase/Decrease in Supply: The law of supply expresses the changes in supply

due to changes in the price of a commodity. It assumes other factors to be constant. In

30/87 9/18/2007 1:31 PM

DHARMENDRA MISHRA

reality the supply changes without any change in the price. This happens due to various

factors other than price.

These factors are:

(1) Rise or fall in the cost.

(2) Change in the prices of factors of production.

(3) Change in the techniques of production etc.

All these factors bring about rise or fall in the supply of a commodity. Such change,

i.e. rise or fall in supply due to effect of other factors, are termed as increase and

decrease in supply respectively.

(1) Increase in supply means more quantity supplied at the same price.

(2) Decrease in supply means less quantity supplied at the same price.

Increase and decrease in supply can be shown by means of the following diagram:

Alongside diagram shows three supply curves ‘S1’ S1’ and ‘S2’. Let us assume that

‘S’ is the original supply curve. On this supply curve ‘OQ’ quantity is supplied at

price ‘OP’.

(1) ‘S1’ shows increase in the supply. On this curve, the price remains same i.e. OP but

quantity supplied rises to OQ1. QQ1’ is thus increase in supply.

(2) ‘S2’ shows decrease in supply. On this curve, at the same price ‘OP’ the quantity

supplied is ‘OQ2’. QQ2’ is thus, decrease in supply.

It can, thus, be seen that new supply curves have to be drawn to show increase and

decrease in supply. An increase in supply can be shown by means of a new supply curve